Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 12

January 14, 2016

The Family of Things

I was delighted to join Helen Shaw of recently as the tenth guest on their excellent ‘The Family of Things’ series of podcasts. You can visit the website here or listen on iTunes.

Here’s the blurb from the Athena Media Website:

January 12, 2016

Author and researcher Eleanor Fitzsimons is our latest guest in The Family of Things.

Eleanor Fitzsimons: Author of Wilde’s Women

Eleanor’s acclaimed biography of Oscar Wilde from the perspective of the women in his life ‘Wilde’s Women’ opens new windows on both Wilde and his work.

Eleanor’s beautifully written and carefully researched study was published in Ireland in Autumn 2015 and is being released in the US this year. In this conversation with presenter Helen Shaw she introduces us to Wilde’s intriguing mother, Jane Wilde, a celebrated writer in her own time, and his much suffering wife Constance LLoyd as well as the women writers who influenced and inspired Wilde.

Eleanor describes her work as ‘recovering’ lost stories of women in history and sees her journey as akin to excavating the past; bringing forth what has been forgotten or obscured.

Wilde’s Women is published by Duckworth Overlook and you can follow Eleanor’s work and story via twitter.

January 12, 2016

John Singer Sargent & Lady Macbeth

Today marks the anniversary of the birth of American-born painter John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), considered the leading portrait painter of his day. One of his most iconic works is his portrait of actress Ellen Terry wearing her costume for Lady Macbeth, a remarkable emerald gown that shimmered with the iridescent wings of the one thousand jewel beetles that had been sewn into it.

Presented by Sir Joseph Duveen 1906

One of my favourite passages in my book, Wilde’s Women describes Oscar Wilde glancing out of the window of his Tite Street home and seeing Terry, a great friend of his, arriving at John Singer Sargent’s Chelsea studio for a sitting. Immediately, he remarked:

The street that on a wet and dreary morning has vouchsafed the vision of Lady Macbeth in full regalia magnificently seated in a four-wheeler can never again be as other streets: it must always be full of wonderful possibilities.

Later, Wilde chose Singer Sargent’s iconic painting for the frontispiece of the July 1889 issue of The Woman’s World, a magazine he edited from 1887-1889.

To his great credit, Sargent suggested that Alice Comyns Carr, a vocal advocate of aesthetic dress who had designed Terry’s magnificent costume, should co-sign his painting since he considered her as much its creator as he. The woman who made Comyns Carr’s design a reality was dressmaker Ada Nettleship, who, along with her team of thirty seamstresses, also made Constance Wilde’s beautiful aesthetic wedding gown. Constance’s gown was the subject of intense public scrutiny and went on public display in March 1884. It was described in society magazine Queen:

…rich creamy satin dress…of a delicate cowslip tint; the bodice, cut square and somewhat low in front, was finished with a high Medici collar; the ample sleeves were puffed; the skirt, made plain, was gathered by a silver girdle of beautiful workmanship, the gift of Mr. Oscar Wilde; the veil of saffron-coloured Indian silk gauze was embroidered with pearls and worn in Marie Stuart fashion; a thick wreath of myrtle leaves crowned her frizzed hair; the dress was ornamented with clusters of myrtle leaves; the large bouquet had as much green in it as white .

Terry loved her Lady Macbeth costume and wrote about it in her autobiography, The Story of My Life:

One of Mrs. Nettle’s greatest triumphs was my Lady Macbeth dress, which she carried out from Mrs Comyns Carr. I am glad to think it is immortalised in Sargent’s picture. From the first I knew that picture was going to be splendid. In my diary for 1888 I was always writing about it:

***

“The picture of me is nearly finished, and I think it is magnificent. The green and blue of the dress is splendid, and the expression as Lady Macbeth holds the crown over her head is quite wonderful . . .”

***

“Sargent’s picture is almost finished, and it really is splendid. Burne-Jones yesterday suggested two or three alterations about the colour which Sargent immediately adopted, but Burne-Jones raves about the picture . . .”

***

“Sargent’s picture is talked of everywhere and quarrelled about as much as my way of playing the part . . .”

***

“Sargent’s Lady Macbeth in the New Gallery is a great success. The picture is the sensation of the year. Of course, opinions differ about it, but there are dense crowds round it day after day.”

***

Since then it has gone nearly over the whole of Europe and is now resting for life in the Tate Gallery. Sargent suggested by this picture all that I should have liked to be able to convey in my acting as Lady Macbeth.

She looks both wonderful and terrible it it.

The dress, which is exhibited at Smallhyde Place, Terry’s former home, was painstakingly restored in 2011.

W. Graham Robertson, Time Was (London, H. Hamilton ltd., 1933, reprinted by Quartet Books, 1981), p.233

January 7, 2016

BARS Blog – On This Day in 1816: Introducing ‘The Year Without a Summer’ Part I

Today saw the publication of my first blog post (but not my last) for the brilliant and very highly regarded British Association for Romantic Studies. Part one of ‘The Year Without a Summer’, which kicks off their commemoration of the events of 1816, appears here. I’ve reproduced it below. Do please visit the blog and comment if you have anything to add.

INTRODUCTION:

We are very pleased to welcome Eleanor Fitzsimons (winner of the 2013 Keats-Shelley Prize and author of Wilde’s Women ) to the BARS blog. This post, part of the ‘On This Day’ series, presents Part I of her essay ‘Every Cloud: How Art and Literature Benefited from a Year Without Summer’. Eleanor’s essay looks at 1816 as the year of no summer and examines the impact that catastrophic weather patterns had on the work of writers and painters such as Turner, Austen and the Shelleys. Part II is to follow.

We think you’ll all agree that this is a great way to introduce 1816 in 2016, a year in which we will be celebrating the bicentenaries of many important Romantic events. If you want to contribute to the ‘On This Day’ series with a post on literary/historical events in 1816, please contact Anna Mercer (anna.mercer@york.ac.uk).

EVERY CLOUD: HOW ART AND LITERATURE BENEFITED FROM A YEAR WITHOUT SUMMER  JMW Turner. Weathercote Cave, near Ingleton, when half-filled with Water and the Entrance Impassable, a watercolour. British Museum

JMW Turner. Weathercote Cave, near Ingleton, when half-filled with Water and the Entrance Impassable, a watercolour. British Museum

Often, an artist must go to great lengths to get the aspect he desires. In 1808, English Romantic landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner scrambled to the bottom of Weathercote Cave, a misnamed pothole situated close to the hamlet of Chapel-le-Dale in North Yorkshire. On reaching a plateau, thirty-three meters below ground level, he unpacked his kit and produced a characteristically vibrant watercolor that captured the wild torrent of water as it tumbled from a cavity situated two-thirds up before terminating in a violent whirlpool at the base of towering rocks. Barely discernible at the foot of the canvas is a tiny figure that appears to represent the artist himself. Turner’s somewhat dramatized representation, which he presented to his great friend and patron Walter Fawkes, is titled simply Weathercote Cave, Yorkshire and can be seen in Sheffield’s Millennium Gallery.

Turner loved to paint the Northern English landscape and experimented with dramatic light and weather effects in his compositions. In recognition of his deep appreciation for the untamed beauty of the region, Longman & Co. commissioned him to produce one-hundred-and-twenty watercolours for incorporation into an illustrated history of Yorkshire, the accompanying text to be supplied by the Reverend Dr. Thomas Dunham Whitaker, the highly respected author of a well-received series of scholarly histories. Although artist and author had worked together on Whitaker’s The History of Whalley (1801) and his The History of Craven (1812), this would be by far their most ambitious collaboration and Turner’s fee of three thousand guineas was the highest paid to a British artist at the time.

On July 12, 1816, Turner left London and travelled north to Farnley Hall near Otley, the home of Walter Fawkes, who was to accompany him on this lucrative tour. Regrettably, the undertaking proved to be far from pleasurable. Although the entire Fawkes family set out with the artist on a series of excursions to local beauty spots, the company disbanded at the end of a week of almost constant rain that culminated in a thorough soaking as they traversed the moors that led to the towering cliffs of Gordale Scar. In order to complete the sketches that would form the basis of his finished watercolours, Turner had no option but to negotiate his way around the vast county of Yorkshire, a distance of more than five hundred miles, alone on horseback in torrential rain. At some point, a capricious wind must have snatched his little sketchbook from his hands, since one page is coated in mud to this day. As he went, he recorded how his progress was hampered by the frightful weather that blighted the summer of 1816: ‘Weather miserably wet. I shall be web-footed like a drake…but I must proceed northwards. Adieu’, he lamented in a letter to watercolorist James Holworthy, dated July 31, 1816

Turner returned to Weathercote cave that summer with the intention of sketching it for inclusion in his book, but days of incessant rain had left it submerged and completely inaccessible; ‘Weathercote full’, he scribbled on the pencil study he made that day. His finished painting, the cumbersomely titled Weathercote Cave, near Ingleton, when half-filled with Water and the Entrance Impassable, a watercolour, is on view in the British Museum; this time the perspective is from above. Days later, the route Turner followed took him across the treacherous Lancaster Sands, a low tide shortcut that intersected Morecombe Bay and was particularly dangerous after heavy rainfall. As he went, he sketched a sodden band of horsemen huddling together in the lee of the Lancaster coach while ferocious rain crashed down from an angry sky. His dramatic Lancaster Sands is housed in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

After all his efforts, Turner must have been disappointed when spiralling costs ensured that the project was scaled down significantly and just one of the proposed seven volumes was published. He had been desperately unfortunate in his timing. The apocalyptic weather that blighted the summer of 1816 was truly exceptional and had its origins in an event that occurred fifteen months earlier and many thousands of miles from England. On the evening of April 10, 1815, the tiny island of Sumbawa in the Indonesian archipelago was rocked when Mount Tambora, the highest mountain in the region and a volcano that was long believed to be extinct, produced its largest eruption for ten thousand years. The outcome was catastrophic. Eyewitness accounts describe how the summit disintegrated, leaving behind a crater measuring three miles wide and half a mile deep. Horrified locals watched open-mouthed as three towering columns of rock-laden fire shot thirty miles skywards and a pyrocastic flow of incandescent ash surged down the mountainside at a speed of in excess of one hundred miles an hour, scouring everything in its path. On reaching the coast, twenty-five miles from its point of origin, this boiling mass cascaded into the sea, destroying aquatic life for miles and forming vast platforms of pumice that blockaded vital ports and inlets.

Ten times the quantity of debris that had buried Pompeii two millennia earlier rained down on Sumbawa and its neighboring islands during what remains to this day the largest recorded eruption in history. On Sumbawa, the cool air that was sucked into the vacuum left by the inexorable rise of superheated air formed a ferocious whirlwind that moved across the ravaged landscape, destroying everything before it. The tiny villages of Tambora and Sanggar, which had clung safely to the slopes of Mount Tambora for generations, were wiped out entirely and an estimated ten thousand people died in an instant. Fresh water sources were contaminated and crops withered in the fields, resulting in the death by starvation of a further eighty thousand inhabitants of the region. For days, the archipelago was battered by towering tsunamis and such was the extent of the devastation and loss of life that the indigenous Tambora language was eradicated forever.

On the northern shore of Eastern Java, three hundred miles away, residents of the city of Surabaya reported that the ground shook beneath their feet. On hearing a series of thunderous roars, startled inhabitants of the island of Sumatra, which lay one thousand miles northwest of Sumbawa, concluded that they had come under attack from some deadly enemy force, although they couldn’t be sure if it were human or supernatural. Within days, the entire region was enveloped in an ash cloud so fine that tiny particles suspended in the Earth’s atmosphere blocked adequate sunlight from filtering through. The entire East Indies, as the region was known, was plunged into an oppressive and unnatural darkness. Within three months an aerosol cloud of sulphide gas compounds had encircled the Earth from pole to pole. Volcanic dust entered the high stratosphere, supplementing debris deposited there by two earlier volcanic eruptions: La Soufrière on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent in 1812, and Mount Mayon on the island of Luzon in the Philippines in 1814. Although he had not witnessed the spectacular eruption of La Soufrière, Turner had painted it, basing his vivid oil painting on a sketch made by Hugh Perry Keane, a barrister and sugar plantation owner who was present that day. Keane wrote an account of the eruption in his diary:

Thurs 30: … in the afternoon the roaring of the mountain increased & at 7 o’clock the Flames burst forth, and the dreadful Eruption began. All night watching it – between 2 & 5 o’clock in the morning, showers of Stones & Earthquakes threatened our immediate Destruction …Wed 6 May: … The Volcano again blazed away from 7 till ½ past 8. Thurs 7: Rose at 7. Drawing the eruption.

Turner’s painting, The Eruption of the Soufrière Mountains in the Island of St Vincent, 1815, can be viewed at the Victoria Gallery and Museum in Liverpool.

All this volcanic activity had a disastrous impact on the weather, and nowhere on Earth escaped the consequences of this latest cataclysm. Across the globe, average temperatures plummeted by five degrees Fahrenheit as weather patterns were thrown into absolute chaos. In time, 1816 would be dubbed ‘the year without summer’. In Asia, unseasonably cold weather coupled with unprecedented early monsoons caused catastrophic floods that destroyed the rice crop and wiped out valuable livestock. Famine gripped China, killing many thousands of her citizens, while India was devastated by a cholera epidemic that swept through the subcontinent. In North America, accumulating snow was observed in the Catskill Mountains as late as June 1816, and it snowed on Independence Day in the southern state of Virginia.

Unprecedented quantities of weirdly-hued, ash-laden snow fell all over Europe and it was still snowing in London as late as July 1816. By the following September, the Thames had frozen and abnormally large hailstones were flattening the wheat and barley crops as they ripened in the fields. In neighboring Ireland, eight weeks of incessant rain resulted in the failure of both the potato crop and the corn harvest, triggering a widespread famine that provided a foretaste of what was to come three decades later. Starvation was followed inexorably by disease. Typhus erupted throughout the British Isles before fanning outwards across Europe and killing tens of thousands of her citizens.

(To be continued…)

January 4, 2016

Bosie: A search for the positive

It can be difficult to find any positive aspects to the character of Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar Wilde’s beloved Bosie and the man generally regarded as the architect of his downfall. Almost every account of Bosie portrays him as a volatile, petulant young man who sacrificed his lover in order to score a point off his brutal and intolerant father, The Marquess of Queensberry.

Yet, friends testify that Bosie could be charming and Wilde’s great ally Ada Leverson described him in glowing terms in Letters to the Sphinx, her memoir of friendship with Oscar:

Very handsome, he had a great look of Shelley. Not only was he an admirable athlete, he had won various cups for running at Oxford, but he had a strong sense of humour and a wit quite of his own and utterly different from Oscar’s. His charm made him extremely popular, and he wrote remarkable poetry.

The fact that Bosie, notoriously litigious, was hovering close by while she wrote this may have had a bearing on her published opinion of him. In the end, he approved of Letters to the Sphinx and told Ada he would have written an introduction had she asked.

Lord Alfred Douglas’s poetry has not withstood the passage of time nor the scandal that overshadowed it. Yet, he was not without talent. The two poems I have reprinted below appeared in an 1894 issue of The Chameleon, an Oxford University periodical that Wilde also contributed to. Both were admitted as evidence during Wilde’s trial and the first, ‘Two Lovers’ contains the phrase ‘the love that dare not speak its name’, often assumed to have been coined by Wilde but composed by Douglas. I’ll leave you to read both and decide for yourselves how talented the generally detested Bosie was. I still can’t warm to him to be honest.

Two Loves

I dreamed I stood upon a little hill,

And at my feet there lay a ground, that seemed

Like a waste garden, flowering at its will

With buds and blossoms. There were pools that dreamed

Black and unruffled; there were white lilies

A few, and crocuses, and violets

Purple or pale, snake-like fritillaries

Scarce seen for the rank grass, and through green nets

Blue eyes of shy peryenche winked in the sun.

And there were curious flowers, before unknown,

Flowers that were stained with moonlight, or with shades

Of Nature’s willful moods; and here a one

That had drunk in the transitory tone

Of one brief moment in a sunset; blades

Of grass that in an hundred springs had been

Slowly but exquisitely nurtured by the stars,

And watered with the scented dew long cupped

In lilies, that for rays of sun had seen

Only God’s glory, for never a sunrise mars

The luminous air of Heaven. Beyond, abrupt,

A grey stone wall. o’ergrown with velvet moss

Uprose; and gazing I stood long, all mazed

To see a place so strange, so sweet, so fair.

And as I stood and marvelled, lo! across

The garden came a youth; one hand he raised

To shield him from the sun, his wind-tossed hair

Was twined with flowers, and in his hand he bore

A purple bunch of bursting grapes, his eyes

Were clear as crystal, naked all was he,

White as the snow on pathless mountains frore,

Red were his lips as red wine-spilith that dyes

A marble floor, his brow chalcedony.

And he came near me, with his lips uncurled

And kind, and caught my hand and kissed my mouth,

And gave me grapes to eat, and said, ‘Sweet friend,

Come I will show thee shadows of the world

And images of life. See from the South

Comes the pale pageant that hath never an end.’

And lo! within the garden of my dream

I saw two walking on a shining plain

Of golden light. The one did joyous seem

And fair and blooming, and a sweet refrain

Came from his lips; he sang of pretty maids

And joyous love of comely girl and boy,

His eyes were bright, and ‘mid the dancing blades

Of golden grass his feet did trip for joy;

And in his hand he held an ivory lute

With strings of gold that were as maidens’ hair,

And sang with voice as tuneful as a flute,

And round his neck three chains of roses were.

But he that was his comrade walked aside;

He was full sad and sweet, and his large eyes

Were strange with wondrous brightness, staring wide

With gazing; and he sighed with many sighs

That moved me, and his cheeks were wan and white

Like pallid lilies, and his lips were red

Like poppies, and his hands he clenched tight,

And yet again unclenched, and his head

Was wreathed with moon-flowers pale as lips of death.

A purple robe he wore, o’erwrought in gold

With the device of a great snake, whose breath

Was fiery flame: which when I did behold

I fell a-weeping, and I cried, ‘Sweet youth,

Tell me why, sad and sighing, thou dost rove

These pleasent realms? I pray thee speak me sooth

What is thy name?’ He said, ‘My name is Love.’

Then straight the first did turn himself to me

And cried, ‘He lieth, for his name is Shame,

But I am Love, and I was wont to be

Alone in this fair garden, till he came

Unasked by night; I am true Love, I fill

The hearts of boy and girl with mutual flame.’

Then sighing, said the other, ‘Have thy will,

I am the love that dare not speak its name.’

In Praise of Shame

Last night unto my bed bethought there came

Our lady of strange dreams, and from an urn

She poured live fire, so that mine eyes did burn

At the sight of it. Anon the floating fame

Took many shapes, and one cried: “I am shame

That walks with Love, I am most wise to turn

Cold lips and limbs to fire; therefore discern

And see my loveliness, and praise my name.”

And afterwords, in radiant garments dressed

With sound of flutes and laughing of glad lips,

A pomp of all the passions passed along

All the night through; till the white phantom ships

Of dawn sailed in. Whereat I said this song,

“Of all sweet passions Shame is the loveliest.”

December 12, 2015

Irish Times Reviews Wilde’s Women

I’m delighted that the Irish Times asked renowned and respected Wilde scholar Dr. Eibhear Walshe to review Wilde’s Women. I’m also very happy with his balanced and insightful evaluation. He describes my book as ‘a lively new study’. There’s a link to the review here.

Wilde’s Women has also been reviewed positively by The Independent here and here, by Kirkus and by We Love This Book (book of the week) among others. There is a round-up of review highlights on my author page on my agent’s website: http://www.andrewlownie.co.uk.

December 7, 2015

The Remarkable Rhoda Broughton

Some of the more peripheral characters in Wilde’s Women are so colourful and pioneering that, although their links to Oscar Wilde were tenuous, I was determined to include them. One was the remarkable Rhoda Broughton, who never took to Wilde, nor he to her.

Although Rhoda Broughton was born in North Wales, her Irish roots stretched deep. Her late mother, Jane Bennett had grown up at 18 Merrion Square. In 1856, the Bennett parents let their home to Gothic novelist Joseph Sheridan le Fanu and his wife, Susanna, Jane’s sister. Le Fanu was well acquainted with William and Jane Wilde, who lived a few doors up. After Suzanna fell into despair and died in mysterious circumstances that were never discussed, Rhoda remained close to her uncle, who encouraged her literary ambitions. On a rainy Sunday afternoon in 1867, as Rhoda struggled through a tedious novel, ‘the spirit moved her to write’. She tossed her dreary book aside and scribbled furiously for six weeks, producing Not Wisely but Too Well, the lurid tale of young Kate Chester, who stops just short of an adulterous affair with the self-regarding Dare Stamer; it was rumoured to be semi-autobiographical.

Le Fanu serialised it in the Dublin University Magazine, which he edited at the time, and persuaded Rhoda to send it to publisher George Bentley & Sons; Bentley turned it down after his editorial reader Geraldine Jewsbury declared it: ‘The most thoroughly sensual tale I have read in English for a long time’. This was exactly what readers wanted. When Not Wisely but Too Well was brought out by the more audacious Tinsley Brothers, it became the first in a string of hugely controversial bestsellers. Three years later, when the circulating libraries lifted their ban on her books, Rhoda’s popularity soared. Yet, she published anonymously until 1872, and most readers assumed she was a man. One unwitting reviewer for the Athenaeum declared:

That the author is not a young woman, but a man, who, in the present story, shows himself destitute of refinement of thought or feeling and ignorant of all that women either are or ought to be, is evident on every page.

Exuberant and ferociously independent, with a well-deserved reputation as a waspish wit, Rhoda divided opinion. Oscar’s friend James Rennell Rodd observed that she had ‘a great heart but acaustic tongue’. Among her supporters were Matthew Arnold, Robert Browning, Thomas Hardy and Henry James, who shared her apparently irrational dislike of Oscar. The Reverend Charles Dodgson, known to us as Lewis Carroll, refused to attend a dinner with her as he ‘greatly disapproved’ of her novels. Anthony Trollope admired her, but despaired at how she ‘made her ladies do and say things which ladies would not do and say’.

They throw themselves at men’s heads, and when they are not accepted only think how they may throw themselves again. Miss Broughton is still so young that I hope she may live to overcome her fault in this direction.

Rhoda insisted she was merely responding to market forces: ‘since the public like it hot and strong, I am not the person to disoblige them’, she declared.

It’s difficult to fathom the animosity that crackled between Oscar and Rhoda as they had much in common: both were blessed with witty and persuasive personalities; both eschewed the narrowly proscribed gender roles imposed by a judgmental Victorian society; and both courted controversy by tackling taboos in their writing. Besides, Oscar was not easily intimidated by anyone. Whatever the reason, he stopped inviting Rhoda to tea and she took this exclusion to heart. Her good friend Ethel Arnold, niece of Matthew and a pioneering journalist in her own right, claimed Rhoda was referring to Oscar when she carped:

I can’t forget those early years of my life, when those from whom I had every right and reason to expect kindness and hospitality showed me nothing but cold incivility. I resent it still, and I shall resent it until my dying day.

Oscar was reportedly furious when Rhoda caricatured him in Second Thoughts as, ‘long pale poet’ Francis Chaloner, who carries a, ‘lotus lily in one pale hand’. Leaving no room for doubt, she furnished Chaloner’s room with a great white lily in a large blue vase that stood alongside easels supporting, ‘various pictures in different stages of finish’. It seems she barely knew him, since she made Chaloner egotistical and humourless. Oscar was understandably wary and novelist Margaret Woods, a mutual friend, recalled:

The last time I met Oscar Wilde was at a private view of the Royal Academy; he then said that he had lately come across Rhoda Broughton and found her tongue as bitter as ever.

He took his revenge by reviewing Broughton’s Betty’s Visions for the Pall Mall Gazette in October 1886: ‘No one can ever say of her that she has tried to separate flippancy from fiction’, he wrote, ‘whatever harsh criticisms may be passed on the construction of her sentences, she at least possesses that one touch of vulgarity that makes the whole world kin’. He closed by declaring: ‘In Philistia lies Miss Broughton’s true sphere and to Philistia she should return’.

Of course, he may have simply disliked her novel, but his words give an insight into how, for all his apparent poise, Oscar was rattled by those who showed him disdain; he could certainly harbor a grudge.

A full description of Wilde’s Women can be found here and the most recent review from The Independent is here.

December 3, 2015

‘Crinolinemania’ and Oscar Wilde’s Tragic Half-Sisters

Today, I came across a fascinating article on ‘Crinolinemania’, which mentioned the danger of fire and suggested that 3,000 British women died in a ten year period when their crinoline dresses caught fire. Included in the fatalities from crinoline fires at this time were Oscar Wilde’s half-sisters, Emily and Mary.

On Halloween night, 31 October 1871, Emily and Mary Wilde, half-sisters to Oscar, attended a ball at Drumaconnor House in County Monaghan. Towards the end of the evening, Andrew Nicholl Reid, their host, invited Emily to take a last turn around the floor. As they waltzed past an open fireplace, Emily’s crinoline dress brushed against the embers and caught alight. When Mary rushed to her sister’s aid, she managed to set her own dress on fire in the attempt.

Eyewitness reports suggest that Reid wrapped his coat around Emily and attempted to extinguish the flames by rolling her on the ground outside. It seems Mary was left to fend for herself. Describing the incident in a letter to his son William several decades later, John Butler Yeats repeated an account given to him by a Mrs. Hime, a friend who was present that night and had noted the ‘prettiness’ of both young women:

‘After Mrs. Hime had left, one of the girls had gone too close to the fire…with the result that she was instantly in flames…both girls died’.

As is evidenced by the dates recorded in the brief notice that appeared in the Northern Standard on 25 November 1871, the women’s suffering was agonising and prolonged:

DIED

At Drumaconnor, on the 8th inst., Mary Wilde

At Drumaconnor, on the 21st inst., Emma [sic] Wilde

Entries in the Coroner’s Inquisition Book for County Monaghan suggest that this incident was the subject of two separate enquiries. The first examined the circumstances of Mary’s death, referring to her throughout as ‘Miss Wylie’, and her father as, ‘Sir Willm Wylie of Dublin’. Although this may have been a simple spelling mistake, it is perhaps more likely to have been a deliberate attempt to protect William’s good name. Certainly, the report refers to a letter from him requesting that no inquest be held since:

‘doing so, might be of fatal consequence to deceased’s sister, who is dangerously ill from severe burns caused to her while endeavoring to extinguish the burning clothes of her sister’

Confirming the details of Mary’s death, the coroner concluded that everything possible had been done to save her. Poor Emily lingered for almost a fortnight more and a second investigation determined that no inquest was required since both had died accidentally and no intervention would have prevented this. Mary and Emily Wilde were buried in the graveyard of St. Molua’s church in Drumnat, County Monaghan. The headstone erected to commemorate them read:

In memory of

2 loving and beloved sisters

Emily Wilde aged 24

And

Mary Wilde aged 22

who lost their lives by accident

in this parish in Novr 1871

They were lovely and pleasant in

their lives and in their death they

were not divided.

(II Samuel Chap. I, v 23)

William was dreadfully upset by the loss of his daughters: Mrs. Hime insisted that his ‘groans could be heard by people outside the house’. Oscar may not have known his half-sisters but, as he was living at home in Merrion Square when the incident had occurred, he must have observed the decline in his father.

Mrs. Hime’s suggestion that the girls’ mother was with them when they died was supported by local rumour. Anecdotal evidence suggests that, for twenty years afterwards, an enigmatic ‘lady in black’ traveled from Dublin to Monaghan by train, before taking a carriage to Drumsnatt cemetery, where she would stand silently by their graveside. When the churchwarden queried her relationship to the tragic young women, she replied that they had been very dear to her. Although the identity of this veiled woman was never discovered, she was almost certainly the same, ‘woman dressed in black and closely veiled’ who arrived at William’s bedside five years later when he lay dying.

Decades later, Oscar, who campaigned for ‘rational dress’ for women, befriended Henrietta Vaughn Stannard, founder of the Anti-Crinoline League.

More information is available in: Eamonn Mulligan and Fr. Brian McCluskey, “The Replay” – A Parish History (Monaghan, Sean McDermott’s G.F.C., 1984), pp.90-1

and

My book Wilde’s Women.

December 1, 2015

Opening Night of The Importance of Being Earnest – 14 February 1895

Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest opens in the Gate Theatre, Dublin tonight and promises to be a glittering and accomplished production. So what was the opening night of the original production like?

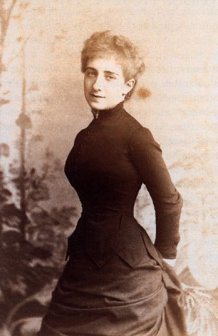

Ada Leverson

Wilde’s great friend Ada Leverson was among the ‘distinguished audience’ that attended the opening performance of The Importance of Being Earnest at the St. James’s Theatre on 14 February 1895. Her lovely tribute to that brilliant occasion, contained in her memoir Letters to the Sphinx, shows that she saw no reason to believe that:

‘the gaiety was not to last, that his life was to become dark, cold, sinister as the atmosphere outside’.

There had been a ferocious snowstorm that day and the street was blocked with carriages depositing patrons who stepped down into a bitterly cold wind. Yet, such inclement conditions did nothing to deter the ‘Wilde fanatics’ who treated the arrival of his audience as an essential part of any performance. Describing how they ‘shouted and cheered the best known people,’ Leverson recalled that:

‘the loudest cheers were for the author who was as well-known as the Bank of England’.

Oscar, recently returned from Algiers where he had holidayed with Lord Alfred Douglas, appeared suntanned and prosperous, and had dressed with what Leverson described as ‘elaborate dandyism and a sort of florid sobriety’. He wore: a coat with a black velvet collar, a green carnation blooming at the buttonhole; a white waistcoat, from which he had hung a large bunch of seals on a black moiré ribbon watch-chain; and white gloves, which he held in his hand, leaving his beloved large green scarab ring visible to all. On any other man, Leverson admitted, this ensemble might be taken for fancy dress, but Oscar, she thought:

‘seemed at ease and to have the look of the last gentleman in Europe’.

Flamboyant as ever, Oscar had declared lily-of-the-valley to be the flower of the evening ‘as a souvenir of an absent friend’ – Lord Alfred Douglas that was and not his wife Constance, also absent – and those gathered sported delicate sprays of that lovely flower: ‘What a rippling, glittering, chattering crowd was that!’ Ada declared, adding:

‘They were certain of some amusement, for if, by exception they did not care for the play, was not Oscar himself sure to do something to amuse them?’

The play did not disappoint. Irene Vanbrugh, who played Gwendolen Fairfax, wrote in To Tell My Story that it ‘went with a delightful ripple of laughter from start to finish’. During the short time she knew Oscar she admired his ‘charm of manner and his elegance’ and the fact that ‘no one was too insignificant for him to take trouble to please’. Years later, she recalled how she:

‘felt tremendously flattered when he congratulated me at one of the rehearsals’.

As the curtain fell at the end of the performance that night, Oscar stepped forward and was greeted with an ovation. He stood smoking while he waited for the applause to subside; the evening was a triumph. Yet, a dangerous drama was unfolding in the vicinity of the theatre that night. The Marquess of Queensberry, father of Lord Alfred Douglas, had grown increasingly frantic in his efforts to stop his son seeing Oscar and had planned to make a public protest by throwing a grotesque tribute, a bouquet of rotting vegetables, onstage.

Oscar was tipped off and foiled his nemesis by persuading the theatre manager, George Alexander, to revoke Queensberry’s ticket and to organise for a cordon of policemen to surround the building. Thwarted, Queensberry hung around outside for hours, muttering with fury, before delivering his monstrous bouquet to the stage door. This was the beginning of the end for Oscar.

For what happens next you could do worse than read my book Wilde’s Women. More information about it here.

For tickets and more information on the Gate Theatre’s production of The Importance of Being Earnest, click here.

Sarah’s Menagerie

Fêted for her talent on-stage, Sarah Bernhardt was also an accomplished sculptor and exhibited at the Paris Salon. In London, she used the proceeds of a sale of her work at the William Russell Galleries to add several exotic creatures to her private menagerie. These included a cheetah and a wolfhound, which she bought from the Cross Zoo in Liverpool. She had hoped to purchase two lions and a dwarf elephant but had be content with seven chameleons, which were thrown in for free by proprietor, Mr. Cross; she had a gold chain made for her favorite, Cross-ci Cross–ça, so that he could sit on her shoulder while attached to her lapel.

Yet, Bernhardt was not always kind to her animals. The death of Ali-Gaga, her alligator, was attributed to his diet of milk and champagne, and she shot her boa constrictor after he swallowed one of her sofa cushions. So why did she keep so many exotic animals? Did she see them as an extension of her own untamed and unusual persona – she was often credited with having animal traits, most notably those of a snake. Did she regard these creatures as beloved pets or living accessories? After all, her tortoise Chrysagére, who died in a fire, had a gilded shell set with brilliant topazes. I’d love to know more about the nature of Bernhardt’s relationship with the animals she owned.

Sarah Bernhardt is just one of the remarkable women in my book Wilde’s Women, read more here.

November 30, 2015

That Wallpaper

On graduating from the Sorbonne, London-born journalist Claire de Pratz, née Zoe Clara Solange Cadiot, worked as an English teacher before becoming a correspondent with both Le Petit Parisien and the Daily News. During her lifetime, she wrote several well received novels and non-fiction books.

On graduating from the Sorbonne, London-born journalist Claire de Pratz, née Zoe Clara Solange Cadiot, worked as an English teacher before becoming a correspondent with both Le Petit Parisien and the Daily News. During her lifetime, she wrote several well received novels and non-fiction books.

In July 1889, when she was aged just seventeen, de Pratz wrote an article, ‘Pierre Loti and His Works’, for The Woman’s World, a magazine that was edited by Oscar Wilde at the time. When she met Wilde in Paris towards the end of his life, she reminded him that he was her first editor and they struck up a friendship.Wilde christened her ‘the good goddess’or ‘la bonne déesse’.

An interview de Pratz gave to Léon Guillot de Saix in L’Européen on 8 May 1929, and her memoir France from Within, give fascinating insights into the final months of Wilde’s life. In these, de Pratz reports that Wilde often spoke of his mother but never of his trials and imprisonment. Clearly devastated by the consequences of his conviction, he asked her: ‘Is there on earth a crime so terrible that in punishment of it a father can be prevented from seeing his children?’

It was to Claire de Pratz that Wilde said of the wallpaper in his room at the Hotel d’Alsace – chocolate flowers on a blue background – ‘my wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other has to go’. Unfortunately, it was to be him. Oscar Wilde died on 30 November 1900. Although he was just 46, he had outlived his father and mother, his sister and brother, and his wife.

Claire de Pratz is one of the remarkable women in my book Wilde’s Women, read more here.

REFERENCE:

L’Européen, 8 Mai 1929, ‘Souvenirs Inedits’ reeferenced in Témoignages d’époque, Claire de Pratz, Rue de Beaux Arts, Numéro 37 : Mars/Avril 2011 http://www.oscholars.com/RBA/thirty-seven/37.13/epoque.htm accessed on 2 March 2015