Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 7

July 11, 2016

Dolly Wilde: An Impossible Burden

Oscar Wilde’s niece Dorothy Ierne Wilde, known as Dolly Wilde,was born on 11 July 1895. To commemorate her birth I have published the Epilogue from Wilde’s Women here on my blog:

EPILOGUE: A WILDE LEGACY

‘Her words flew out like soap bubbles’ – Bettina Bergery on her friend Dolly Wilde[i]

On 10 April 1941, when the chambermaid who serviced the block of flats located at Twenty Chesham Place in Belgravia used her pass key to gain entry to number 83, she must have been horrified to discover the lifeless body of a woman in her mid-forties slumped half in and half out of her bed. Although the occupant, recently arrived, had a history of suicide attempts, and several bottles labelled paraldehyde – an over-the-counter depressant of the central nervous system used to treat alcoholism and chronic insomnia – were discovered in her flat, there was no evidence to suggest she had overdosed deliberately. For that reason, Coroner Mr. Neville Stafford recorded an open verdict, declaring that this ‘independent spinster’, as she was described on her death certificate, ‘came to her death through causes unascertainable’.[ii]

The dead woman was Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Wilde, daughter of Willie and niece of Oscar. At the time, she was undergoing treatment for breast cancer, diagnosed two years earlier. Although her doctors advocated it strongly, Dolly had prevaricated about surgery, preferring a combination of pharmaceutical and new age treatments that included a heroin cure and a brief pilgrimage to Lourdes. As a result, the cancer had metastacised and an autopsy revealed traces in her lungs.

Fatally self-destructive, Dolly had battled several addictions; years of prodigious drug and alcohol consumption had compromised her health. Although she tried to conceal her worst excesses, anecdotes described her slipping a syringe from her handbag and injecting herself in the thigh under the table at dinner parties, or emerging from a variety of bathrooms with telltale traces of white powder under her nose.[iii]

Dolly photographed by Cecil Beaton

Dolly Wilde was born into chaos and poverty to a father lost to alcohol and a mother whose inability to cope led her to abandon her infant daughter in a ‘country convent’.[iv] From the day of her birth, three months after the imprisonment of her Uncle Oscar, her life was governed by turmoil and impulsiveness. In adulthood, she was so outrageous that had she been fictional she would have lacked credibility. While in her teens, she ran away to war torn France, where she drove an ambulance and developed a taste for fast cars and foreign women. One early paramour was her Montparnasse flat mate, Joe Carstairs, the cross-dressing Standard Oil heiress who later seduced Marlene Dietrich. Afterwards, Dolly drifted through her twenties, living out of a suitcase in a series of hotel suites, spare bedrooms and borrowed apartments. Since she hated ‘flat reality’, the antidote she seized upon was to live hard and travel constantly, a lifestyle that took a toll on her wellbeing.[v]

An incorrigible womaniser, Dolly specialised in ‘emergency seductions’ and went through a string of lovers.[vi] She once made a pass at Zelda Fitzgerald, much to Scott’s annoyance; he captured her in an unflattering cameo in Tender is the Night as incorrigible lesbian seductress Vivien Taube, but he deleted the passage from the published version.[vii] Dolly also had a passionate affair with Russian-American actress Alla Nazimova, who produced and starred in a silent film adaptation of Salomé (1923) that drew heavily on Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for Oscar’s book. Dolly prided herself on her irresistibility to women and men and, although she showed no interest in anything beyond friendship, several men proposed marriage to her.

Dolly was always promiscuous, but the love of her life was Natalie Clifford Barney, two decades her senior and a woman with a self-professed obsession with Oscar. Natalie’s decision to install Dolly in her ‘blue bedroom’ at 20 Rue Jacob, where she hosted her celebrated Friday salon may have been influenced by her resemblance to her iconic uncle.

Natalie Clifford Barney as ‘The Happy Prince’ (artist: Carolus-Duran)

In 1882, when six-year-old Natalie was holidaying at Long Beach with her mother Alice, she was chased by a pack of taunting boys. She ran headlong into Oscar, who scooped her onto his knee and comforted her by telling her a wonderful tale.[viii] At ten, she insisted on being painted as his happy prince, dressed exotically in medieval green and gold. In her teens, she wrote a letter of sympathy to Oscar in HM Prison Reading, and she served on committees that commemorated his birth and his death. As an adult, Natalie had a fling with poet Olive Custance, Oscar’s onetime rival for the affections of poet John Grey. Through her, she befriended Lord Alfred Douglas. Her ultimate Wildean trophy was Dolly.

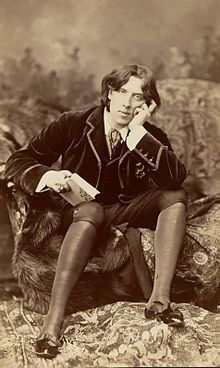

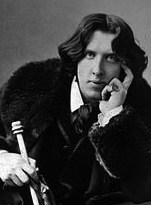

Although Dolly never met her famous uncle, her pale, elongated face, remarkable blue-grey eyes, shock of dark hair and affected pose, conjured him up for all who met her. She inherited too his ‘clear, low, musical voice’, insatiable appetite for cigarettes and inability to regulate her chaotic finances.[ix] Her friends nicknamed her Oscaria, and Dolly herself declared: ‘I am more like Oscar than Oscar himself’.[x] In her ‘Letter from Paris’ column in July 1930, Janet Flanner, Paris correspondent of The New Yorker, described Dolly attending a bal-masqué dressed as Oscar, ‘looking both important and earnest’.[xi] When H.G. Wells bumped into her at the Paris PEN Club, he declared himself delighted to meet at last a feminine Wilde.

Dolly as Oscar

Everyone who knew Dolly said she should write. Days after her birth, her grandmother Jane declared her ‘magnificent!!!’, and described her as: ‘A force of intellect and power’. Dolly, she assured her daughter-in-law Constance, would ‘most certainly write books’.[xii] When she was almost four, her mother, Lily told Oscar that little Dolly, had ‘a fair share of the family brains’.[xiii] This weight of expectation overshadowed her life. Although she left scant evidence to support it, a hyperbolic obituary written by her great friend Victor Cunard, diplomat and Times correspondent in Venice, stated that Dolly ‘carried on with undiminished wit the family tradition of conversational brilliance,’ and concluded:

‘Epigram and paradox are the weapons of the Wilde family, and none of its members has used them more humanely nor more effectively than Dorothy’.[xiv]

Yet, there is little to indicate that Dolly shared any measure of Oscar’s brilliance. Wishful thinking may simply have projected his wit onto the blank canvas she supplied. She left nothing more tangible than personal letters, and many of the testimonies collected in a posthumous tribute, In Memory of Dorothy Ierne Wilde: Oscaria, published privately by Natalie Clifford Barney ten years after Dolly’s death, suggest that what wit she possessed was ephemeral. Her friend Bettina Bergery wrote of her, ‘she scintillated with so many epigrams, all delivered at once – that no one had time to remember any…Her words flew out like soap bubbles’.[xv] Yet she had some ability to charm: Cartoonist Osbert Lancaster called her ‘irrepressible and wholly delightful’.[xvi] Her last lover, actress Gwen Farrer described her as a ‘jolly and high spirited woman, with many friends’.[xvii]

Dolly’s first cousin Vyvyan Holland discovered her existence when she was brought to his house by a mutual friend; she was twenty-two years old by then and he was thirty-one. She never met Cyril, who died in the war she had been so eager to join. Vyvyan’s relationship with Dolly was an uneasy one; she must have been infuriating at times with her posing and her insistence in finding refuge behind a narcotic fog. She could be a messy drunk: on one occasion the manager of the luxurious Hotel Montalembert on Saint Germain des Prés, Dolly’s favourite Parisian hotel, contacted Natalie Clifford Barney, who was probably paying the bill, complaining of piercing cries and heart wrenching groans that were disturbing his other guests, and asking her to please remove Dolly to a sanatorium. Undoubtedly, she knew anguish and she almost succeeded with at least one of her four recorded suicide attempts.

Dolly left little trace of her life, just a bundle of letters and an ambiguous turn as ‘Doll Furious’ in Ladies Almanack, an obscure novel celebrating the splendid lesbian cult of Clifford Barney. It was written by her friend Djuna Barnes, whose grandmother, the irrepressible Zadel Turner Barnes used to attend Jane Wilde’s Saturdays.

NOTES AND REFERENCES:

[i] Bettina Bergery, ‘What’s in a Name?’ In Memory of Dorothy Ierne Wilde, ed. Natalie Clifford Barney (Paris, privately printed, 1952), quoted in Joan Schenkar, Truly Wilde: The unsettling Story of Dolly Wilde, Oscar’s Unusual Niece (London, Virago, 2000), p.116

[ii] ‘Death Mystery: Open verdict on Oscar Wilde’s niece’, Gloucestershire Echo, Monday 12 May 1941, p.1

[iii] This story originated with Osbert Lancaster and is reported in Schenkar, p.130

[iv] Letter from Lily Wilde to Oscar Wilde, 7 May 1899, Clark, Finzi 2416

[v] Schenkar, p.284

[vi] Schenkar, p.314

[vii] John William Crowley, The White Logic: Alcoholism and Gender in American Modernist Fiction (Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1994), p.86

[viii] Recounted in Natalie Clifford Barney, Aventures de l’esprit (Paris, Émile-Paul Frères 1929)

[ix] Schenkar, p.26

[x] Natalie Clifford Barney from In Memory of Dorothy Ierne Wilde quoted in Schenkar, p.239

[xi] Janet Flanner, ‘Letter from Paris, New Yorker, 16 July 1930

[xii] Letter from Jane Wilde to Constance Wilde, July 1895, Eccles Collection 81731

[xiii] Letter from Lily Wilde to Oscar Wilde, 7 May 1899, Clark, Finzi, 2416

[xiv] ‘Miss Dorothy Wilde’, The Times, 14 April 1941, p.6

[xv] Bettina Bergery quoted in Schenkar, p.116

[xvi] Osbert Lancaster, With an Eye to the Future (London, Murray, 1967), p.136

[xvii] Daily Mail, 12 April 1941

[xviii] Rosamond Harcourt-Smith from In Memory of Dorothy Ierne Wilde quoted in Schenkar, p.117

June 30, 2016

Wilde Tales: What of the Stories We Will Never Hear?

When Aimée Lowther was a girl, she would rush home to write down the wonderful stories that her friend Oscar told her. Years later, in 1912, four of these stories were published in The Mask: A Quarterly Journal of the Art of the Theatre. They were ‘The Poet’, ‘The Actress’, ‘Simon of Cyrene’ and ‘Jezebel’. Each was captioned, ‘An unpublished story by Oscar Wilde’, and prefaced with the words:

This story was told by Wilde to Miss Aimée Lowther when a child and written out by her. A few copies were privately printed but this is the first time it has been given to the public.

Lowther was in her forties by then, and had enjoyed some success as a playwright and amateur actress. As Wilde’s life had ended twelve years earlier, in room sixteen of the Hotel d’Alsace in Paris, he was unable to verify her claims. However, one of these stories, ‘The Actress’, was believed to have been inspired by his great friend Ellen Terry. Edward Gordon Craig, editor of The Mask, was Terry’s son and Aimée Lowther was her close confidante.

Wilde loved Lowther. It is recorded in Richard Ellmann’s biography on Wilde that, when she was just fifteen, he declared: “Aimée, if you were only a boy I could adore you.” In return, she remained loyal to him to the end, and a visit from her could lift his spirits even when he was at his lowest ebb: ‘…your friendship is a blossom on the crown of thorns that my life has become’, he told her in a letter, now collected in The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. In A Pride of Terrys, Marguerite Steen wrote that, in 1900, Lowther and Ellen Terry spotted a much diminished Oscar Wilde gazing longingly through the window of a Parisian patisserie and biting his fingers with hunger. They invited him to dine, and were greatly relieved when he ‘sparkled just as of old’, but they never saw him again.

The veracity of Lowther’s claim that Wilde told these four stories to her is borne out by a letter he sent her in August 1899, asking that she not allow the publication of ‘the little poem in prose I call ‘The Poet’’, as it was due to ‘appear next week in a Paris magazine above my own signature’. No such magazine has ever been identified. However, confusion arose when Gabrielle Enthoven, a passionate collector of theatrical memorabilia, claimed that Wilde had told these stories to her. In 1890, she commissioned the private printing of Echoes, a limited edition, twelve-page pamphlet containing the four stories in question. Aimée Lowther owned a copy of Echoes, which she later gave to Oscar’s younger son, Vyvyan, and the stories reproduced in both Echoes and The Mask are almost word for word the same.

confusion arose when Gabrielle Enthoven, a passionate collector of theatrical memorabilia, claimed that Wilde had told these stories to her. In 1890, she commissioned the private printing of Echoes, a limited edition, twelve-page pamphlet containing the four stories in question. Aimée Lowther owned a copy of Echoes, which she later gave to Oscar’s younger son, Vyvyan, and the stories reproduced in both Echoes and The Mask are almost word for word the same.

Of course it is entirely possible that Wilde told the same stories to both women. He was a born storyteller and could harness the power of the spoken word in a way that was reminiscent of the seanchaí (a figure familiar to him from his father’s careful documenting of the oral tradition that thrived in his native Ireland).

In A Woman of No Importance, Wilde has his Lord Illingworth say, ‘A man who can dominate a London dinner-table can dominate the world’. His own popularity was assured by his eagerness to entertain, to the extent that society hostesses took to including the words ‘to meet Oscar Wilde’ on invitations, in a bid to boost attendance at their gatherings.

Wilde’s popularity as a storyteller was enhanced by the fact that he possessed an exceptionally melodious voice, which Lord Alfred Douglas described as ‘golden’. Frank Dyall, the actor who played Merriman in the first production of The Importance of Being Ernest, recalled Wilde’s voice as being:

…of the brown velvet order – mellifluous, rounded, in a sense giving it a plummy quality, rather on the adenotic side, but practically pure cello, and very pleasing.

~ from Hesketh Pearson’s The Life of Oscar Wilde

To add drama to a narrative, Wilde would modulate his voice from a whisper to a cry of triumph, losing himself in his stories to the extent that those present described him as seeming dazed by the effort of telling them. Yet his true power was in the words. In his auto-biography, William Butler Yeats, Wilde’s contemporary and compatriot, said of him: ‘I had never before heard a man talking in perfect sentences, as if he had written them all overnight with labour and yet all spontaneous.’

One guest fortunate enough to be present at a lunch hosted by publisher and bon vivant Frank Harris described how Wilde’s musical voice and infectious laughter cut through the lively chatter, causing everyone present to fall silent in order to listen exclusively to him. In response, Wilde filled the hours that followed with humorous anecdotes, embryonic plotlines for plays he was contemplating, macabre tales told in the style of Edgar Allan Poe, and his distinctive take on instructive Bible stories. Frank Harris published several of these spontaneous stories under the heading ‘Poems in Prose’, in The Fortnightly Review, but it is probable that they lost something in the transcribing. Robert Ross was a great friend and literary executor to Wilde and, in his introduction to Essays and Lectures by Oscar Wilde, he claimed:

To those who remember hearing them from Wilde’s lips, there must always be a feeling of disappointment on reading them. [Ross] overloaded their ornament when he came to transcribe them, and some of his friends did not hesitate to make that criticism personally.

Although he made no attempt to alter his accent, Wilde spoke excellent, ponderous French and, in Paris, earned a reputation as ‘the poet who tells fantastic tales’. His visit to that city in 1891 was described by L’Echo de Paris as, ‘le “great event” des salons littéraires parisiens’. Young André Gide, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for literature towards the end of his long life, found Wilde utterly captivating and met with him every day for three weeks. After parting from Wilde, Gide felt unable to put pen to paper for several days. In correspondence published by the University of Chicago Press, it is noted that, when he finally made contact with poet Paul Valéry on Christmas Eve, 1891, Gide asked him to ‘please forgive my silence: since Wilde, I hardly exist anymore’.Once, as Gide and Wilde were dining at the home of Princess Ouroussoff, wife of the Russian ambassador to France, the princess swore that a halo appeared around Wilde’s head as he talked.

Princess Ouroussoff was not alone in attributing otherworldly properties to Wilde’s flights of fancy. Lord Alfred Douglas believed that Wilde could cure depression or disease simply by speaking to an afflicted person for just five minutes. The artist W. Graham Robertson, who described Wilde as ‘a born raconteur’ in his auto-biography Time Was, was certain that Wilde had cured him of a ‘violent toothache’ by telling his stories ‘so brilliantly that for an hour and a half I laughed without ceasing’. Some were moved despite themselves. The poet Ernest Dowson attested that Wilde ‘had such a wonderful vitality and joie de vivre that after some hours of his society even a pessimist like myself is infected by it’.

Princess Ouroussoff was not alone in attributing otherworldly properties to Wilde’s flights of fancy. Lord Alfred Douglas believed that Wilde could cure depression or disease simply by speaking to an afflicted person for just five minutes. The artist W. Graham Robertson, who described Wilde as ‘a born raconteur’ in his auto-biography Time Was, was certain that Wilde had cured him of a ‘violent toothache’ by telling his stories ‘so brilliantly that for an hour and a half I laughed without ceasing’. Some were moved despite themselves. The poet Ernest Dowson attested that Wilde ‘had such a wonderful vitality and joie de vivre that after some hours of his society even a pessimist like myself is infected by it’.

Although he was a very public raconteur, Wilde saved some of his best stories for home, remarking that it was the duty of every father to invent fairytales for his children. In his memoir, Son of Oscar Wilde, Vyvyan Holland wrote of a ‘never-ending-supply’ of fairy stories and tales of adventure, many of them inspired by the imaginings of Jules Verne, Robert Louis Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling; Wilde always was a literary magpie. Holland recalled one particular bedtime story, reminiscent of ‘The Elves and the Shoemaker’, which described the helpful fairies who lived in the great bottles of coloured water found in the windows of chemist shops. They would dance about at night before making the pills that the chemist would dispense the next day.

Many of Wilde’s bedtime stories were rooted in the misty mythology of the West of Ireland, where his father had once kept a holiday cottage at Moytura. He kept his boys rapt with his description of the ‘great melancholy carp’ that lived in the deep waters of Lough Corrib, refusing to move off the bottom of the lake unless Wilde himself called them up with the ancient Irish songs that his father had taught him. At times, Wilde was moved to tears by his own ingenuity. His eyes glistened as he told his boys the story of ‘The Selfish Giant’ and when his elder son, Cyril, wondered why, Wilde replied that really beautiful things always made him cry.

Many of Wilde’s stories started life in the nursery of his Tite Street home, but in a letter to Amelie Rives Chanler, from 1889, he was adamant that they were intended ‘not for children, but for childlike people from eighteen to eighty’. His great friend Helena Swanwick recognised that the only stimulus he needed to tell a story was to be in the company of good listeners. In her memoir, I Have Been Young, she describes Wilde:

…his indolent figure, lounging in an easy chair, his face alive with delight in what he was saying, pouring out stories and descriptions, whose extravagance piled up and up.

Once, after she allowed her scepticism to show, he enquired playfully: ‘You don’t believe me, Miss Nelly? I assure you… well, it’s as good as true.’

Such was Wilde’s prolificacy that only a tiny fraction of the stories he told ever made it into print, and he would commit a story to paper only if the reaction of his audience merited it. If one of his stories was published, Wilde would often dedicate it to a society hostess whose largesse he had enjoyed. The stories in his collection A House of Pomegranates, which is dedicated to his wife, Constance, pay tribute to four such women: ‘The Young King’ is dedicated to Margaret, Lady Brooke, who would one day lend great support to Constance; ‘The Fisherman and his Soul’ was chosen for Princess Alice of Monaco — Wilde told her it was the best of the four; ‘The Star-Child’ was saved for the socialite Margot Tennant, who had recently become Mrs. Asquith, and would later disown Wilde when he most needed her support; and ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’ was dedicated to Lady Desborough, ‘as a slight return for the entrancing day at Taplow’. Later, Lady Desborough received a ‘little book that contains a story, two stories in fact that I told you at Taplow’. This ‘little book’ was Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories.

Such was Wilde’s prolificacy that only a tiny fraction of the stories he told ever made it into print, and he would commit a story to paper only if the reaction of his audience merited it. If one of his stories was published, Wilde would often dedicate it to a society hostess whose largesse he had enjoyed. The stories in his collection A House of Pomegranates, which is dedicated to his wife, Constance, pay tribute to four such women: ‘The Young King’ is dedicated to Margaret, Lady Brooke, who would one day lend great support to Constance; ‘The Fisherman and his Soul’ was chosen for Princess Alice of Monaco — Wilde told her it was the best of the four; ‘The Star-Child’ was saved for the socialite Margot Tennant, who had recently become Mrs. Asquith, and would later disown Wilde when he most needed her support; and ‘The Birthday of the Infanta’ was dedicated to Lady Desborough, ‘as a slight return for the entrancing day at Taplow’. Later, Lady Desborough received a ‘little book that contains a story, two stories in fact that I told you at Taplow’. This ‘little book’ was Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories.

After Wilde was imprisoned, Adela Schuster, whom he christened ‘Miss Tiny’ on account of her size, believed that his stories might save him. She wrote to his friend More Adey:

Could not Mr. Wilde now write down some of the lovely tales he used to tell me? […] I think the mere reminder of some of his tales may set his mind in that direction and stir the impulse to write.

In her letter, Schuster recalled, in particular, two stories that Wilde had told her: one concerning ‘a nursing sister who killed the man whom she was nursing’; and a second that was about ‘two souls on the banks of the Nile’. To these Adey added, ‘the moving sphere story and the one about the Problem and the Lunatic’.

Sadly these, and many others, never found their way into print. In a letter to Robert Ross, dated May 1898, Wilde wrote: ‘I really must begin The Sphere.’ He never did, although Frank Harris did publish a version of it as ‘The Irony of Chance (after O.W.)’. Ross sheds light on the inspiration for many of the stories that ‘unfortunately exist only in the memories of friends’, confirming that they were:

Invented on the spur of the moment, or inspired by the chance observation of someone who managed to get the traditional word in edgeways; or they were developed from some phrase in a book Wilde might have read during the day.

How disappointing it is that we will never hear them. How I envy those who enjoyed that great pleasure.

Note: This essay was first published in Thresholds as The Unrecorded Stories of Oscar Wilde and is an edited version of Chapter 13 of Wilde’s Women.

June 23, 2016

Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner

I’ve written a post on the pioneering South African feminist writer Olive Schreiner for the Sheroes of History Blog. Here’s a link:

South African writer Olive Schreiner was born in what is now Lesotho on 24 March 1855. The ninth of twelve children born to Rebecca Lyndall and her husband, Gottlob Schreiner (1814–1876), a German-born missionary, she and just six of her siblings survived childhood. In adulthood, she suffered debilitating ill-health, exacerbated for a time by grinding poverty.

For a time, Schreiner earned a living as a governess and teacher, but she devoted her free time to writing The Story of an African Farm, a radical feminist novel informed by her experience of growing up in Africa. As soon as she could afford to, she sailed for Britain where she hoped to train as a doctor. Unfortunately, although she attended lectures at the London School of Medicine for Women, established in 1874 by an association of pioneering women physicians, ill-health prevented her from completing her training.

View original post 584 more words

June 17, 2016

Maria Casavetti Zambaco (1843-1914)

Having inherited her father’s vast fortune in 1858, Maria Casavetti Zambaco, a British artist and model of Greek descent, led a more independent life than most women of her time. She was even known to go about unchaperoned while still unmarried.

Maria Zambaco by Edward Burne-Jones (1871)

A talented artist, she studied at the Slade School under French painter, etcher, sculptor, and medallist Alphonse Legros. In Paris, she studied sculpture under Auguste Rodin. Her work was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1887, and at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in London in 1889. She also exhibited at the prestigious Paris Salon. The British Museum holds several of her medals, including this one depicting the head of a young girl:

[image error]

British Museum

Zambaco’s love life was rather chaotic. In her teens she was wooed by George du Maurier, satirical cartoonist and grandfather of Daphne; when she showed no interest in him, du Maurier described her as ‘rude and unapproachable but of great talent and a really wonderful beauty’. Aged 18, she married Dr. Demetrius Zambaco, who was eleven years her senior. They had two children together but the marriage was not a success and she moved back to her mother after six years.

In 1866, Zambaco met Edward Burne-Jones when her mother commissioned him to paint her. As the subject was left to him, he chose an episode from Cupid and Psyche, which he worked on for several months. Although Burne-Jones was married at the time, he embarked on a tempestuous affair with Zambaco that lasted several years.

Burne-Jones Cupid finds Psyche Photo (c) Trustees of the British Museum

Burne-Jones treated Zambaco as a peer. They read Homer and Virgil together and she trained as an artist under him. She also sat as a model for some of his most iconic paintings including The Beguiling of Merlin, one of Oscar Wilde’s favourites. Zambaco repeatedly tried to persuade Burne-Jones to leave his wife but he refused and she is rumoured to have involved him in a suicide pact, convincing him to wade into the canal in Regent’s Park with her. The attempt failed and the affair ended, but they remained friends afterwards and she was by far his most influential muse.

Zambaco also sat as a model for artists George Frederick Watts, James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, but she became more interested in developing her own artistic talent and produced award winning sculptural works.

Naturally, since she features here and in my book Wilde’s Women, Zambaco had a connection to Oscar Wilde. She lived much of her life in Paris and presided over an important artistic salon. It was she who introduced Oscar Wilde to his friend and biographer Robert Sherard. Years earlier, when writing about Burne-Jones’s The Beguiling of Merlin, Wilde had described Zambaco as ‘a tall, lithe woman, beautiful and subtle to look on, like a snake’.

Burne-Jones: The Beguiling of Merlin Lady Lever Art Gallery, Merseyside

Maria Zambaco died in Paris in 1914.

For more on Edward Burne-Jones and his relationship with Maria Casavetti Zambaco you can read Fiona MacCarthy’s book ‘The Last Pre-Raphaelite’. There’s an extract here.

There is also a brilliant online exhibition of her work and that of her contemporaries Aglaia (née Ionides) Coronio (1834-1906)and Marie (née Spartali) Stillman (1843-1927) available via the University of York here. Together these women were known as ‘The Three Graces’.

June 13, 2016

Wilde’s Half-Brother, Dr Henry Wilson

Dr Henry Wilson

In June 1877, Oscar Wilde wrote to his friend Reginald ‘Kitten’ Harding expressing his sorrow at the unexpected death of a cousin. This ‘cousin’ was Wilde’s half-brother, Dr. Henry Wilson, one of three children born to his father, William, before his marriage to Jane Elgee. Each one of these children, a son and two daughters, was acknowledged privately by their father and supported by him.

Henry Wilson, who was thirteen at the time of his father’s wedding, was commonly passed off as his nephew. Yet, Wilde took a keen interest in his eldest son’s progress, paying for his education and bringing him into St. Mark’s Ophthalmic Hospital, the hospital he had founded, to work alongside him until he succeeded him as senior surgeon.

Wilson’s death came as a dreadful shock to his family. Just four days earlier, Oscar had attended a dinner party he hosted and had attested that his half-brother seemed in perfect health. Wilson had fallen ill that evening, an illness that Oscar attributed to a chill he had caught while out riding.

Despite the best efforts of six colleagues who remained with him during his final days, Henry Wilson died of pneumonia on 13 June 1877. He was thirty-nine years old and had never married. An obituary in the Dublin Journal of Medical Science described Wilson as being ‘under the guardianship of his relative Sir William Wilde’, and eulogised him as a learned and popular man with a ‘kindly and cheerful manner’ and a ‘genial nature’.

Willie and Oscar Wilde were chief mourners at Wilson’s funeral and fully expected to be the main beneficiaries of his will. Instead, he bequeathed £8,000, subject to a life interest granted to two unnamed female relatives, to St. Mark’s Ophthalmic Hospital.

REFERENCES

‘In Memoriam Henry Wilson’ Dublin Journal of Medical Science, Volume 64, Issue 1, 2 July 1877, pp.98-100

June 5, 2016

The Birth of Cyril Wilde

Constance Wilde (later Holland) with her son Cyril

Baby Cyril Wilde arrived into the world at ten forty-five on the morning of 5 June 1885. That same day, his father, Oscar, insisted in a letter that his ‘amazing boy’ knew him quite well already. He told a friend, actor Norman Forbes Robertson, that Cyril was ‘wonderful’.

By all accounts, Cyril, and his younger brother Vyvyan, who arrived eighteen-months later, were lovely, boisterous lads who enjoyed more freedom than many of their Victorian contemporaries. Eyewitness accounts confirm that their parents were indulgent and very fond of them.

Both boys adored their father, who was kind-hearted and playful and perfectly happy to join in with nursery games, even if they involved getting down on all fours in order to play the part of a bear, a lion, a horse or whatever was required of him. He once spent an entire afternoon repairing a beloved wooden fort.

Boisterous games often spilled out into the beautiful dining-room of their Tite Street home, where all three would dodge between the legs of the spindly white chairs before tumbling together in a tangle on the floor. When they grew tired, Oscar would tell them the most wonderful stories.

Further Reading:

Son of Oscar Wilde by Vyvyan Holland is a remarkable account of a fractured childhood, and gives unparalleled insights into a life that is perhaps more speculated about than any other. It contains a warm account of the time he and his brother had with their father, which lends added poignancy to the tragedy that they never saw him again after 1895.

Wilde’s Women also contains an account of Cyril’s life.

Cyril died young and his tragic final years are described here.

Vyvyan Holland, Son of Oscar Wilde (Robinson, Revised edition, 1999), p.53

Letter to Nellie Lloyd, 5 June 1885, Complete Letters, p.261

June 2, 2016

Thomas Hardy’s Influential Mother, Jemima

To commemorate the birth of Thomas Hardy on 2 June 1840, I’m going to take a break from writing about Oscar Wilde’s mother, Jane, to write instead about Hardy’s mother, Jemima.

Jemima Hardy

Jemima, a former maidservant and cook from an impoverished and volatile Dorset family, acquired a love of reading from her own mother, Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Hand. Her sophisticated literary tastes ran to Latin poetry and French romances in their English translation, and it was said that Dante’s Divine Comedy was her favourite book.

When Jemima was thirteen, she was sent to work as a domestic servant. Aged twenty-six, her marriage to Thomas Hardy, a master mason and building contractor, was arranged by her family when it was discovered that she was pregnant with young Thomas. Happily, their marriage was a stable and contented one.

It was Jemima who instilled in her son Thomas a love of literature. She taught him to read and write before he turned four, and she sent him to school from the age of eight to sixteen. When he was ten, she enrolled him in a progressive non-conformist school run by the British and Foreign School Society in Dorchester. There, he learnt Latin and French among other subjects, but his favourite pastime was to read.

Perhaps it was a mark of Hardy’s gratitude that he maintained a great affection for his mother throughout her life. He wrote a poem to mark her death:

After the Last Breath

(J.H. 1813–1904)

There’s no more to be done, or feared, or hoped;

None now need watch, speak low, and list, and tire;

No irksome crease outsmoothed, no pillow sloped

Does she require.

Blankly we gaze. We are free to go or stay;

Our morrow’s anxious plans have missed their aim;

Whether we leave to-night or wait till day

Counts as the same.

The lettered vessels of medicaments

Seem asking wherefore we have set them here;

Each palliative its silly face presents

As useless gear.

And yet we feel that something savours well;

We note a numb relief withheld before;

Our well-beloved is prisoner in the cell

Of Time no more.

We see by littles now the deft achievement

Whereby she has escaped the Wrongers all,

In view of which our momentary bereavement

Outshapes but small.

Thomas Hardy

For more on hardy and his literary life read: http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/h...

May 28, 2016

Happy Anniversary Oscar & Constance!

Happy 132nd wedding anniversary to Oscar and Constance, who married on 29 May 1884. To mark the occasion, the brilliant Oscar Wilde Society has arranged for an OSCANCE memorial to be unveiled at St. James’s Church, Paddington by the couple’s grandson Merlin Holland.

St. James’s Church, Paddington

Although Oscar was in the public eye by then, the uncertain health of Constance’s grandfather, John Horatio Lloyd, ensured that their wedding was an unexpectedly low-key event. Admittance, by invitation only, was restricted to family and close friends. Nevertheless, the event was covered extensively by the press of the day.

According to the Edinburgh Evening News, Oscar ‘bore himself with calm dignity’. He deprived the gossip columnists of copy by wearing a perfectly ordinary blue morning frock-coat with grey trousers, although he did display ‘a touch of pink in his neck tie’.

The ceremony may have been subdued, but the bride and groom were jubilant. The Lady’s Pictorial reported that:

The newly-married pair, as they came down the long aisle arm-in-arm, looked as hundreds of newly-married people have looked before – the bridegroom happy and exultant; the bride with a tender flush on her face, and a happy hopeful light in her soft brown eyes.

Constance

Constance’s lovely dress was described in society magazine Queen as a:

…rich creamy satin dress…of a delicate cowslip tint; the bodice, cut square and somewhat low in front, was finished with a high Medici collar; the ample sleeves were puffed; the skirt, made plain, was gathered by a silver girdle of beautiful workmanship, the gift of Mr. Oscar Wilde; the veil of saffron-coloured Indian silk gauze was embroidered with pearls and worn in Marie Stuart fashion; a thick wreath of myrtle leaves crowned her frizzed hair; the dress was ornamented with clusters of myrtle leaves; the large bouquet had as much green in it as white.

Lady Jane Wilde, Oscar’s mother, looked resplendent in grey satin, trimmed with a chenille fringe and topped off with a high crowned hat adorned with ostrich feathers. It was reported in the Lancaster Gazette that she:

‘“snatched” her new daughter to her heart with some effusion’.

After a modest reception at the Lancaster Gate home of John Horatio Lloyd, the newlyweds boarded the boat-train to Dover and travelled on to Paris; ‘few married couples ever carried better wishes with them,’ gushed the Aberdeen Evening Express.

Lovely to think of them sharing such happiness.

May 26, 2016

Did Jane Wilde Inform Bram Stoker’s Dracula?

May 26 is World Dracula Day, so named to mark to anniversary of the publication of Bram Stoker’s magnificent Gothic novel. One of my favourite holiday experiences of all time was when I sat reading Dracula in the window seat of a house in Grape Lane, Whitby (the Yorkshire seaside town where much of Dracula is set). I could just about see the harbour where Stoker’s mysterious ship comes in under full sail and his demonic black dog disembarks before running up the 199 steps towards Whitby Abbey.

Of course, there are many connections between Stoker and the Wilde family, which you can read about in Wilde’s Women. He was particularly friendly with Lady Jane Wilde; ‘I suppose you dine with Lady Wilde as usual,’ his father asked in one letter between them.

I like to imagine Bram reading Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms & Superstitions of Ireland by his great friend Jane Wilde (who would almost certainly have given him a copy) and thinking ‘hmmmm’.

In Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms & Superstitions of Ireland, published in 1887, ten years before Dracula, Jane explained that:

‘…in the Transylvanian legends and superstitions…many will be found identical with the Irish’.

Particularly significant, she argued, was the shared belief that:

‘the dead are only in a trance; they can hear everything but can make no sign’.

Jane’s descriptions of horned witches who drew blood from victims as they slept might well have informed Bram’s ‘weird sisters’, three female vampires who fed on the blood of men.

While she told tales of men who assumed the shape of wolves and monstrous, soul-devouring hounds, his best loved book reverberates with the howling of wolves, and his Dracula assumes the shape of ‘an immense dog’.

May 24, 2016

Oscar Wilde’s Great-Grandfather and 1798

The first clashes of the Irish rebellion of 1798 took place just after dawn on this day (24 May). Much of the action took place in the county of Wexford in the South-East of Ireland, and one of the families caught up in hostilities was that of the Reverend John Elgee, Grandfather of Lady Jane Wilde, the foremost of Wilde’s Women.

John Elgee, Rector of Wexford by then, almost lost his life during the rising of 1798, when his home was occupied by a bloodthirsty band of local pike-men. Although many Protestant clergymen and their families were murdered at that time, the Elgee family was spared; otherwise there would never have been an Oscar Wilde. Local historians attributed this act of mercy to the gratitude of a former prisoner to whom Elgee had shown kindness in his role as inspector of the local gaol.

In Ancient Cures, Charms, and Usages of Ireland: Contributions to Irish Lore, Jane Wilde recorded details of her family’s involvement:

‘On the day the rebels entered Wexford, the rector Archdeacon Elgee, my grandfather, assembled a few of his parishioners in the church to partake of the sacrament together, knowing that a dreadful death awaited them. On his return, the rebels were already forcing their way into his house; they seized him, and the pikes were already at his breast, when a man stepped forth and told of some great act of kindness which the Archdeacon had shown his family.

In an instant the feeling changed, and the leader gave orders that the Archdeacon and all that belonged to him should be held safe from harm. A rebel guard was set over his house and not a single act of violence was permitted. But that same evening all the leading gentlemen of the town were dragged from their houses and piked by the rebels upon Wexford Bridge.’

Wexford Bridge (c) 1798

Rector Elgee, widely admired in the community, was appointed Mayor of Wexford in 1802 and elevated to Archdeacon of Leighlin in 1804. Jane was little more than a baby when he died in 1823. A tribute in the Waterford Mirror lamented the passing of a man who had, ‘died universally regretted – as he had lived beloved by all his parishioners’.

One example is James Bentley Gordon, History of the Rebellion in Ireland in the Year 1798 (Dublin, T. Hurst, 1803), p.176. An article in the Belfast Newsletter of 12 March 1824 repeats this version. Elgee undoubtedly had a connection with Wexford Gaol: Parliamentary records suggest that he acted as prison inspector and procured supplies for the prisoners. Details of payments to purchase provisions, along with an application for a salary on behalf of Rev. John Elgee are included in accounts presented to the House of Commons from the East India Company, printed in 1808, p.429

Lady Jane Wilde, Ancient Cures, Charms, and Usages of Ireland: Contributions to Irish Lore (London, Ward & Downey, 1890) pp.228-9n