Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 11

February 4, 2016

BARS Blog – On This Day in 1816: Introducing ‘The Year Without a Summer’ Part II

Today saw the publication of my first blog post (but not my last) for the brilliant and very highly regarded British Association for Romantic Studies. Part one of ‘The Year Without a Summer’, which kicked off their commemoration of the events of 1816, appeared here. I’ve reproduced part two below and it can be found here. Do please visit the blog and comment if you have anything to add.

INTRODUCTION:

We are very pleased to welcome Eleanor Fitzsimons (winner of the 2013 Keats-Shelley Prize and author of Wilde’s Women ) to the BARS blog. This post, part of the ‘On This Day’ series, presents Part II of her essay ‘Every Cloud: How Art and Literature Benefited from a Year Without Summer’. Eleanor’s essay looks at 1816 as the year of no summer and examines the impact that catastrophic weather patterns had on the work of writers and painters such as Turner, Austen and the Shelleys. Part II is to follow.

We think you’ll all agree that this is a great way to introduce 1816 in 2016, a year in which we will be celebrating the bicentenaries of many important Romantic events. If you want to contribute to the ‘On This Day’ series with a post on literary/historical events in 1816, please contact Anna Mercer (anna.mercer@york.ac.uk).

EVERY CLOUD: HOW ART AND LITERATURE BENEFITED FROM A YEAR WITHOUT SUMMER: Part II

Jane Austen by Cassandra Austen (c) 1810, National Portrait Gallery

The English novelist Jane Austen spent the summer of 1816 in the village of Chawton in Hampshire, where she shared a cottage with her sister Cassandra, her chronically ill mother and an assortment of nieces and nephews. In a letter to her niece Anna, written on June 23, 1816, Austen described how their neighbor Mrs. Digweed had been soaked to the skin by a rain shower she characterized as ‘beyond everything’. The appalling weather kept the author indoors: ‘Oh! It rains again; it beats against the window’, she told her nephew Edward, adding, ‘such weather gives one little temptation to be out. It is really too bad, and it has been for a long time, much worse that anybody can bear and I begin to think it will never be fine again’. On July 9, Austen, accompanied by her niece Mary Jane, attempted a jaunt to nearby Farringdon in the family’s donkey cart: ‘we were obliged to turn back before we got there’, she told Edward, ‘but not soon enough to avoid a Pelter all the way home’.

At the time, Austen was working on The Elliots, which she later renamed Persuasion. Although she had thought the book finished in July, as she sat indoors watching rain cascade down her windowpanes, she decided that she was dissatisfied with its ending and spent a further three weeks rewriting the final two chapters. By autumn, Austen’s health had deteriorated dramatically. Her back ached continuously and she felt unable to walk even a short distance. Although she blamed her wretchedness on rheumatism brought on by the unusually damp weather, her symptoms were indicative of something far more serious, possibly Addison’s disease, a tubercular disease of the kidneys. By winter she was housebound, but she remained stoic: ‘Air and exercise is what I want’ she assured her family. In May 1817, Jane Austen was taken by carriage in the pouring rain to Winchester Hospital where she died in the arms of her sister Cassandra on July 18, 1817.

The world had been forecast to end precisely twelve months earlier, on July 18, 1816. Seeking an explanation for the bizarre weather, a superstitious populace had concluded that such weird portents could only indicate an impending apocalypse. This supernatural thinking was forgivable. News of the eruption of Mount Tambora did not reach Europe for many months and, even if it had, the link between volcanic eruptions and unseasonal weather was not recognized until 1913, when William Jackson Humphreys, an American physicist and atmospheric researcher with the U. S. Weather Bureau, presented evidence to the Cleveland meeting of the Astronomical and Astrophysical Society of America. However, in the absence of a sound scientific explanation, news of the planet’s imminent demise was widely accepted. Such fear mongering prompted opium-addled poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge to remark ‘this end of the World Weather is sadly against me by preventing all exercise’. At the time, Coleridge had left his home in the Lake District and was living in London as a patient and houseguest of Dr. James Gillman, who had prescribed daily walks as an integral part of his treatment regime.

Attempts were made to calm the situation. While newspapers carried soothing editorials, clerics held public prayer services and recommended mass demonstrations of piety, but apocalyptic fear was fuelled by a series of sunspots, visible to the naked eye, which were interpreted as proof of the disintegration of the sun. Keen to strike a lighter note in the face of mass hysteria, English satirist William Hone published ‘Napoleon and the Spots on the Sun or the Regents Waltz’, a satirical ditty in which he claimed that Napoleon had escaped from the Island of St. Helena and invaded the sun in revenge for his defeat at Waterloo. The solution proposed by Hone involved catapulting the Prince of Wales, then Prince Regent, into space where he would engage in hand-to-hand combat with Britain’s nemesis.

The citizens of Europe had every reason to feel aggrieved with their rulers. During the early years of the nineteenth century, the entire continent had been ravaged by a serious of ruinous wars that left its populace ill-equipped to withstand the destruction wrought by devastating weather patterns. Bands of unemployed veterans recently returned from the grueling Napoleonic campaign now faced rocketing food prices, destitution and disease. They had surely had their fill of wet weather too. It had poured with rain on June 18, 1815, the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, turning the battlefield into a quagmire and compounding the horror of the occasion. By 1816, these battle-weary men were back in Britain, feeling abandoned by their rulers. In response to the lack of gratitude for the loyalty they had shown to the Crown, these men took to rioting in the streets, looting everything they could get their hands on and considering it no more than their due.

Widespread unrest culminated in the ‘Bread or Blood’ riots that erupted in East Anglia, home to painter John Constable who lived in the Suffolk village of East Bergholt. Constable, a committed Tory who had lost two cousins at Waterloo, had little patience with the band of armed veterans and laborers that marched on the cathedral town of Ely in protest at food shortages, holding the town’s magistrates hostage and fighting a running battle against the militia. Rather than incorporate the inclement weather into his work, as Turner had, Constable did precisely the opposite, painting idyllic representations of bucolic Albion as a reaction to this social and climactic upheaval; The Wheatfield and Flatford Mill, both painted in 1816, are examples of this.

As ever, enterprising folk found opportunity in a crisis. When the German oat crop failed, leaving people unable to feed their horses, the entrepreneurial Baron Karl Christian Ludwig von Drais de Sauerbrun enjoyed a sudden upsurge of interest in his latest invention, the bicycle. There were cultural benefits too: the spectacular sunsets and ominous sulphurous skies that lit the skies with bilious yellow and orange tints, found their way into the paintings of J.M.W. Turner and recent scientific analysis demonstrates that the works he completed in the years immediately following major volcanic eruptions contain significantly higher levels of red pigmentation in his extravagant sunsets. His Chichester Canal, which is included in the Tate Britain collection, captures the distinctive sepia hue so characteristic of refracted sunlight.

Turner paid a high price for accessing such beauty. He was dogged by bad weather all summer long and left Yorkshire to travel throughout continental Europe where conditions were, if anything, even worse than those he had endured at home. This caused him to exclaim:

Rain, Rain, Rain, day after day. Italy deluged, Switzerland a wash-pot, Neufchatel, Bienne and Morat Lakes all in one. All chance of getting over the Simplon or any of the passes now vanished like the morning mist.

Switzerland in particular was battered. Prodigious rainfall filled Lake Geneva, adding two meters to the water level and flooding low-lying districts for miles around. Homes were destroyed, livelihoods lost and livestock drowned, their bloated corpses found floating across the brimming lake. Turner arrived just in time to witness the disastrous wheat harvest that resulted in a serious flour shortage and inflated the price of a loaf of bread to the extent that Swiss dinner guests were asked, politely, to bring their own.

Eighteen-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, who called herself Mary Shelley by then, had been in Switzerland since June 1816. Along with her lover, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and her stepsister, Claire Claremont, she was renting the modest Maison Chapuis on the southern shore of Lake Geneva, close to the opulent Villa Diodati that was occupied by Lord Byron and his entourage. Unremitting rain put paid to any plans for alpine walks, boating trips and sightseeing excursions. In her journal, Mary recorded: ‘it proved a wet, ungenial summer, and incessant rain often confined us for days to the house’. When Byron and Shelley embarked on a sailing trip to the medieval fortress of Château de Chillon, torrential rain delayed their return, obliging them to take refuge for two days in the Hôtel de L’Ancre in the lakeside resort of Ouchy. It was during this enforced hiatus that Byron wrote his narrative poem The Prisoner of Chillon.

Confined to Byron’s rented villa, the party huddled by the fireside, recounting chilling tales of the supernatural as lightning cleft the skies above and thunder reverberated off the mountains that surrounded them. Byron found the weather frustrating and complained of the ‘stupid mists, fogs and perpetual density’, but enforced confinement allowed him to complete several works including his autobiographical ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’, which includes a vivid description of the storms that raged across the lake as the ‘big rain comes dancing to the earth’. His apocalyptic poem ‘Darkness’, which describes an ‘icy Earth’ presided over by an ‘extinguished sun’, was written, by his own account, on ‘a celebrated dark day, on which fowls went to roost at noon, and the candles were lighted as at midnight’. It contains the line: ‘Morn came and went, and came, and brought no day’.

In late July, in defiance of the weather, the Shelleys set out to visit Mer de Glace, a vast glacier that nestled in the Chamonix Valley at the base of Mont Blanc, but a dense white mist descended and Mary recorded that ‘the rain continued in torrents’. Shelley incorporated the rain-swollen torrent of the River Arve into his poem ‘Mont Blanc: Lines written in the Vale of Chamouni’, and he used that image to denote great power. Although the weather curtailed their activities, all were enthralled by the frequent and frenetic thunderstorms that reverberated off the mountains, imbuing the landscape with a supernatural light. Mary described these tempests as ‘grander and more terrific than I have ever seen before’, and described in her journal how, as each discharge of lightning rent the clouds, the landscape was: ‘illuminated for an instant, when a pitchy blackness succeeded, and the thunder came in frightful bursts over our heads amid the darkness’.

Safe indoors, they would read aloud from Fantasmagoriana, a collection of ghost stories. In Shelley’s preface to Frankenstein, he described how hearing these stories ‘excited in us a playful desire of imitation’. Byron issued a challenge to those present that they should write a story ‘founded on some supernatural occurrence’; he started immediately on ‘A Fragment’, which is recognized as one of the first stories to feature a vampire and hailed as a key inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Percy Bysshe Shelley by Amelia Curren 1819, National Portrait Gallery

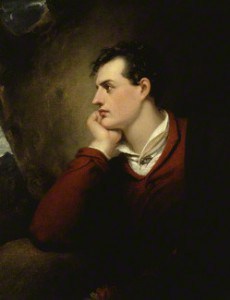

Lord Byron by Richard Westall, 1813, National Portrait Gallery

Although Mary struggled to settle on a theme, she found inspiration in a conversation between Byron and Shelley concerning the reanimation of a corpse. In her preface to the third edition of Frankenstein or the modern Prometheus, she described how her gothic tale of rejection and revenge was informed by a ‘waking dream’ that she experienced later that night, when the ‘bright and shining moon’ hanging over Lake Geneva shone through the shutters into the bedroom she shared with Shelley. This preface also mentions the ‘incessant rain’ that beat against the windows of the Villa Diodati, keeping them all indoors. Percussive rain accompanied the creation of Frankenstein and found its way into her story; ‘rain pattered dismally against the panes’ as the eponymous scientist gave life to his monster.

Mary punctuated her narrative with the thunderstorms that raged above. In one instance, Victor Frankenstein describes a storm that ‘advanced from behind the mountains of Jura’:

The thunder burst at once with frightful loudness from various quarters of the heavens. I remained, while the storm lasted, watching its progress with curiosity and delight. As I stood at the door, on a sudden I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak, which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump. When we visited it the next morning, we found the tree shattered in a singular manner. It was not splintered by the shock, but entirely reduced to thin ribbands of wood. I never beheld anything so utterly destroyed.

Later, he is described watching a terrifying storm from the same lakeside spot where Mary herself stood. His words echo almost exactly the entry Mary made in her journal on June 1, 1816:

…the darkness and storm increased every minute, and the thunder burst with a terrific crash over my head. It was echoed from Saleve, the Juras, and the Alps of Savoy; vivid flashes of lightning dazzled my eyes, illuminating the lake, making it appear like a vast sheet of fire; then for an instant everything seemed of a pitchy darkness, until the eye recovered itself from the preceding flash. The storm, as is often the case in Switzerland, appeared at once in various parts of the heavens.

Weather is inescapable in the works of the Romantics, and never before had they experienced the conditions that characterized the ‘year without summer’. Yet, had a benign Swiss summer encouraged Byron and the Shelleys to abandon their fireside tales and embark on Alpine walks instead, we might not have Frankenstein, or at a stretch, Dracula. Had clement weather permitted Jane Austen to leave her cottage in Chawton, her wonderful Persuasion might have a different, less satisfying ending. The incessant downpour that prevented J.M.W. Turner from entering Weathercote Cave swelled the Ure, the Washburn and the Wharfe, and filled the high glacial Malham Tarn, providing him with dramatic subjects at every turn. At Malham Cove, Turner painted the arc of a rainbow. He sketched children as they gazed down on the raging torrent at Cotter Force and he captured the torrential descent of the Aysgarth waterfalls. He even hired a guide to take him underground so that he could sketch Dow Cave by candlelight, keeping one ear to the roar of the swollen river. The old adage reminds us that every cloud has a silver lining. Certainly, there was no shortage of clouds during the bleak summer of 1816 and the dramatic weather that prevailed permeates some of our best loved art and literature.

February 1, 2016

Me on Joyce & Wilde & At It Again

To tie in with my earlier post, here is my heartfelt speech from this evening’s launch of Romping Through Dubliners:

‘I first encountered At It Again, in the form of Maite and Niall, at the Oscar Wilde Festival in Galway in September 2015, and I was struck by the energy and joy they injected into Romping Through Dorian Gray, their witty guide to Wilde’s lush novel; a dynamism and irreverence that was very much in keeping with the approach taken by Oscar himself. I was also struck at that time by the great enthusiasm with which they – and happily I – were welcomed into the inner circle of those who keep Wilde’s work fresh in the public mind, a generosity of spirit that is common to all true lovers of literature in my experience.

Since the task of finding new angles on Wilde, one of the most closely examined men in the world, second only to Joyce perhaps, was thought to be next to impossible, I realised that I, with my focus on Wilde’s Women, and they, with their delightful romp through Dorian Gray, were kindred spirits who shared a belief that there is always something new to say. Their enticing approach to Wilde, Stoker and Joyce has ensured that I’ve taken a huge interest in their activities ever since.

Irish people can be justifiably proud of the wealth of great literature that our tiny island has produced, yet, sometimes, we make the mistake of being a little too reverential about the whole affair. It’s not uncommon for us to feel intimidated by the towering reputation of a writer as magnificently talented as James Joyce. As a result we may feel that his work is not for the likes of us when, in fact, it was written with precisely us in mind!

Decades, ago, when I was in my twenties and working in London, an English colleague, on learning that I was a Dubliner, rushed to my desk to talk about Ulysses, his favourite book: ‘What bit had I enjoyed most,’ he wondered? ‘Exactly which of the Martello Towers that punctuate our eastern shoreline featured in the opening chapter?’ On and on he gushed until, finally, I had to stop him and admit that I had never read Ulysses. He turned on his heel in disgust, leaving me wondering why I, a Dubliner through and through, somehow believed that Ulysses was not for me, a book to be endured rather than enjoyed. It was the beginning of a lasting curiosity.

Dubliners, Joyce’s collection of short stories, provides the perfect entry point for anyone keen to read his work. Although published in 1914, Joyce had written the interlinked stories between the years 1904 and 1907. Publishers were wary of the forthright language and fretted about bringing out a book in which so many of Joyce’s contemporaries were immediately recognisable and might take umbrage; Dubliners, of course, were far more likely to take umbrage at being omitted rather than included. The fact that Dubliners was rejected by numerous publishing houses, including London-based Grant Richards, its eventual publisher, provides a lesson in perseverance for us all.

In writing Dubliners, Joyce held up a mirror to Dublin society with the intention of provoking a citywide epiphany. A proponent of individualism, like Wilde before him, he hoped that, once confronted with reality, his compatriots might question their circumstances and crawl out from beneath the twin yoke of church and state. Like everything Joyce wrote, Dubliners was radical and challenging; it was neither pompous nor staid. It was aimed at ordinary, decent, and not so decent, Dubliners as much as it was at scholars and academics, who were welcome to read it too.

By insisting that Dubliners is for everyone and by prompting us to engage with this wonderful city, Romping Through Dubliners, a manual, is a truly fitting companion piece to Joyce’s original. It gives ownership back to the people it was written for. It is very telling that the word ‘fun’ is included on the very first page, a word that some people, although no one present in this room I suspect, forget to apply to Joyce.

With their intriguing maps and tips for dressing up, or ‘cosplay’ as my teenage son would say, Romping Through Dubliners recaptures the immediacy that was always present in Joyce’s work. Its interactivity calls to mind the ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ books that so captivated children of the 1970s and 1980s, myself included, who were invited to determine the outcome of their own quest; an acknowledged source of inspiration for the At It Again manuals. By suggesting tie-in activities such as ‘sip sherry & talk politely about death’ Romping Through Dubliners pokes gentle fun at the quirky customs and habits of Dubliners that were so brilliantly exposed in the original

The playful illustrations add vitality and capture the essence of the original. The whole ethos of At It Again, and of Joyce too, is exemplified in a quote from ‘An Encounter’ highlighted on page 14:

‘Real adventures do not happen to people who remain at home. They must be sought abroad’.

‘Abroad’ in the ‘here, there and everywhere’ sense of the word that is. The scope of the At It Again’ team’s ambition is illuminated by their suggestion on page 31: WHY DON’T YOU: ‘Pursue your dreams’. It gives me great pleasure to introduce Maite, Niall, Jessica and James of At It Again, a dynamic bunch who describe themselves with great accuracy as ‘cultural treasure hunters who bring Irish literature to life’. Long may they continue to do so!’

Joyce on Wilde

I’m all about James Joyce today, since it is my great honour to have been asked by At It Again to say a few words at the launch of their delightful little manual Romping Through Dubliners in The James Joyce Centre on North Great Georges Street, Dublin 1.

Yet, I can’t let this opportunity pass without mentioning Joyce’s commentary on his compatriot Oscar Wilde. In March 1909, a production of the opera Salome by Richard Strauss, which was based on Wilde’s play of the same name, opened at the Teatro Verdi in Trieste, where Joyce was living at the time. To coincide with this event, ‘Oscar Wilde: il poeta di “Salomé”’ [Oscar Wilde: The Poet of Salome]*, Joyce’s lengthy analysis of Wilde’s life, was published in Il Piccolo della Sera on 24 March 1909.

Joyce opened by analysing Wilde’s elaborate name – ‘Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde’ – and commenting on its appropriateness, since the original Oscar, son of Ossian in Celtic mythology, had been ‘treacherously killed by the hand of his host as he sat at table’. Wilde too, Joyce believed, met his death ‘in the flower of his years as he sat at table, crowned with false vine leaves and discussing Plato’.

While he acknowledged the considerable influence that Jane Wilde exerted over her younger son, Joyce did not believe this worked to his advantage. He wrote:

‘His mother’s susceptible temperament revived in the young man, and, beginning with himself, he resolved to put into practice a theory of beauty that was partly original and partly derived from the books of Pater and Ruskin. He provoked the jeers of the public by proclaiming and practising a reform in dress and in the appearance of the home.’

While acknowledging the success Wilde enjoyed with his sharp social comedies, Joyce is damning in his assessment of the position of the Irish comedic playwright in English society, writing:

‘In the tradition of the Irish writers of comedy that runs from the days of Sheridan and Goldsmith to Bernard Shaw, Wilde became, like them, court jester to the English.’

Joyce believed, with good reason, that Wilde frittered his new-found wealth away on ‘a series of unworthy friends’. Since his popularity was superficial and unsustainable, as soon as he fell from favour, ‘[h]is fall was greeted by a howl of puritanical joy’.

Not one to miss an opportunity to have a pop at the faith of his youth, Joyce, who had been devout in his early years but had turned his back on religion, took the opportunity to castigate Wilde for his late conversion:

He died a Roman Catholic, adding another facet to his public life by the repudiation of his wild doctrine. After having mocked the idols of the market place, he bent his knees, sad and repentant that he had once been the singer of the divinity of joy, and closed the book of his spirit’s rebellion with an act of spiritual dedication.

Ultimately, he saw Wilde as a victim of a system that tolerated him only as long as he posed no real threat.

‘Whether he was innocent or guilty of the charges brought against him, he undoubtedly was a scapegoat. His greater crime was that he had caused a scandal in England, and it is well known that the English authorities did everything possible to persuade him to flee before they issued an order for his arrest. An employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs stated during the trial that, in London alone, there are more than 20,000 persons under police surveillance, but they remain footloose until they provoke a scandal.’

In the end, Joyce believed that the turn of Wilde’s life was

‘the logical and inescapable product of the Anglo-Saxon college and university system, with its secrecy and restrictions’.

And he mourned the fact that Wilde’s literary reputation had been destroyed:

‘his brilliant books sparkling with epigrams (which made him, in the view of some people, the most penetrating speaker of the past century), these are now divided booty’.

Today we have reclaimed Wilde’s work and his reputation, and we celebrate his brilliance in myriad ways. One fitting example of the revival of our brilliant Oscar is to be found in Romping Through Dorian Gray, At It Again’s witty and interactive companion to his lush novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. In it, we are urged to ‘yield to temptation’, an activity that Oscar embraced wholeheartedly.

*The translation of ‘Oscar Wilde: il poeta di “Salomé”’ comes from The critical writings of James Joyce

January 28, 2016

Yeats on Wilde

Today marks the anniversary of the death of our great poet W.B. Yeats, a man we’ve been hearing about rather a lot recently, since 2015 marked the 150 year anniversary of his birth. I’ve decided to take this opportunity to comment on his connections to the Wilde family.

W.B. Yeats as a young man

Although Yeats knew the family well, and thought them ‘very imaginative and learned’, his retrospective commentary, on Oscar in particular, benefits from hindsight and should be treated with caution. Yet, his observations offer valuable insights into the lives of Lady Jane Wilde and Oscar Wilde in particular. Perhaps most telling of all is a remark he includes in Letters to The New Island (1934):

‘When one listens to her [Lady Jane Wilde] and remembers that Sir William Wilde was in his day a famous raconteur, one finds it no way wonderful that Oscar Wilde should be the most finished talker of our time’

He certainly thought highly of Oscar’s abilities as a raconteur, and wrote of him in The Trembling of the Veil:

‘I had never before heard a man talking in perfect sentences, as if he had written them all overnight with labour and yet all spontaneous’.

In 1887, Ward and Downey published Jane Wilde’s Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions of Ireland, a compendium of folk tales, several of them collected by her late husband, William while he was collecting data for the censuses of 1841 and 1851 in Ireland. This collection was praised lavishly by Yeats who referred to it liberally in his own Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry.

Lady Jane Wilde

This admiration prompted him to ask novelist Katharine Tynan to write him a letter of introduction to Jane; he expressed the hope that he would find her:

‘as delightful as her book …as delightful as she certainly is unconventional’.

Jane embraced him as ‘my Irish poet’ and he acknowledged that London had few better talkers. He wrote of her that she:

‘longed always perhaps, though certainly amid much self-mockery, for some impossible splendour of character and circumstance’.

In time, he would call Maud Gonne, his great love and muse, ‘The New Speranza’.

Yeats admired Oscar’s writing too. When he was compiling an anthology of Irish verse, he asked permission to include ‘Requiescat’, the poem inspired by the tragic early death of Oscar’s sister Isola. In reply, Oscar wrote:

‘I don’t know that I think ‘Requiescat’ very typical of my work’.

Undeterred, Yeats used it anyway and it was hailed as, ‘the brightest gem in this collection’. Later, he commented on Oscar’s only novel, declaring: ‘Dorian Gray, with all its faults, is a wonderful book’. He realised how astute it was of Oscar to dedicate many of his stories to society women who could further his career, and he saw through the surface conventionality of his compatriot’s plays.

‘the famous paradoxes, the rapid sketches of men and women of society, the mockery of most things under heaven, are delightful,’

he declared.

Yet he realised that the only real people in A Woman of No Importance were the villains and non-conformists, the:

‘tragic and emotional people, the people who are important to the story, Mrs. Arbuthnot, Gerald Arbuthnot, and Hester Worsley, are conventions of the stage.’

Yeats also believed that, when it came to his personal life, Oscar was constructing an elaborate facade. He recalled spending Christmas Day, 1888 with Oscar and Constance, writing:

‘I remember thinking that the perfect harmony of his [Oscar’s] life there, with his beautiful wife and his two young children, suggested some deliberate artistic composition’.

Decades after Oscar’s early death, Yeats admitted ‘of late years I have often explained Wilde to myself by his family history’. Certainly, he speculated that Oscar might have fled to safety had his mother, veteran of an earlier libel action, not declared:

‘If you stay, even if you go to prison, you will always be my son, it will make no difference to my affection, but if you go, I will never speak to you again’.

Much of the information for this post comes from: W.B. Yeats. 1922. The Trembling of the Veil. London: Werner Laurie

January 23, 2016

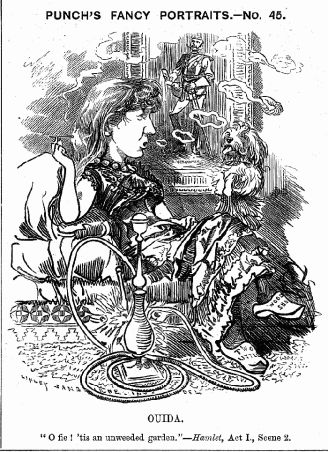

OUIDA: THE FORGOTTEN NOVELIST WHO INSPIRED OSCAR WILDE

When Michael Dirda reviewed Wilde’s Women for the Washington Post earlier this week, he drew attention to two women novelists in particular, writing:

In one fascinating chapter, Fitzsimons writes at length about the two best-selling female authors of the time, Marie Corelli, whose mystical novels, such as “The Sorrows of Satan,” were admired by Gladstone, Thackeray and Queen Victoria, and the sybaritic, luxury-loving Ouida. The latter is now faintly remembered for her foreign-legion classic “Under Two Flags,” but she made her reputation with witty, decadent works such as “Moths” and “Princess Napraxine” that may have influenced Wilde when he came to write his own novel.

Since it’s the weekend, and since she is one of my absolute favourites of Wilde’s Women, I have written this longer piece on the remarkable Ouida.

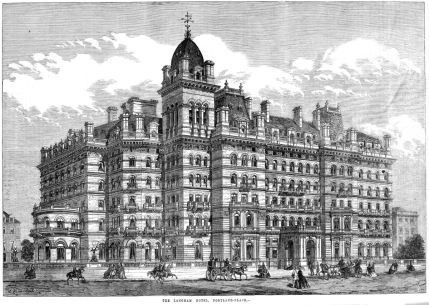

It is 1867. Where in London would an inventive woman with a healthy bank balance, desirous of inhabiting a rarefied world of beauty and luxury, choose to live? Why, the Langham Hotel of course. One of the hotel’s most celebrated residents was Maria Louisa Ramé, known as Ouida, her own childhood mispronunciation of her middle name. Although largely forgotten, she was one of the most successful novelists England has ever produced.

Ouida was born into her maternal grandmother’s modest home in Bury St. Edmunds, on New Year’s Day 1839, to local woman Susan Sutton and her husband, Louis Ramé, a Guernsey native who made an erratic living teaching French. Ramé, an exotic charmer who hinted at a close friendship with Louis Napoleon, left his wife before their only child arrived.

Monument to Ouida in Bury St. Edmunds

Ouida dreamed big and began writing novels in her teens. Before a single word had been published, she convinced her mother and grandmother to move to London on the strength of her future success. Her confidence was rewarded when Tinsley Brothers paid fifty pounds – almost five thousand in today’s terms – for the rights to Held in Bondage, her first novel. It became an instant sensation.

As her celebrity grew, and with it her bank balance, Ouida took a suite of rooms in the Langham Hotel, a luxurious establishment finished to the highest standards with ornate Italianate public areas, modern plumbing, and a series of ‘rising rooms’, hydraulic lifts that carried guests from floor to floor. Her gatherings there were scandalous. Since she considered women ‘ungenerous, cruel, pitiless’, her guest list was made up almost exclusively of men.

One aristocratic woman of her acquaintance complained that Ouida ‘was not charitable to her own sex, and was very intolerant of women who had made a shipwreck of their own lives’. It was said that the only woman she ever invited to her suite at the Langham was the formidable Isabel Burton, wife of explorer, Richard.

Ouida’s celebrated a lush aristocratic existence and her aesthetic style kicked against the fetters imposed by Victorian notions of prudence, rationality and worth. She pioneered a new style of language, studded with witty epigrams, which allowed her characters to indulge in the most subversive behaviour imaginable. Her paeans to beauty earned her a devoted following amongst Aesthetes and Pre-Raphaelites, but she was also hugely popular with the shop girls and footmen who frequented the circulating libraries or saved up for six shilling, single-volume reprints of her latest novel.

In appearance and manner, Ouida adopted the standards she set for her heroines. She cultivated a wildly eccentric look and allowed her mane of blonde hair to tumble down her back until she was well into her thirties. Her dresses, made to her own design by Charles Worth, had short sleeves and curtailed hemlines contrived to show off her dainty hands and tiny feet to best effect. She favoured pale shades, white satin in particular, and was said to make her timid mother wear black for contrast.

Yet, a rival described her as ‘small, insignificant-looking with no pretension to beauty, her harsh voice, and manner almost grotesque in its affectation’. Ouida didn’t seem to notice, perhaps she simply didn’t care. She loved to hold court, cutting through the chatter with a ‘harsh and unpleasing’ voice that was likened by an acquaintance to ‘a carving-knife’. When one brave soul shushed her during a musical performance, her indignant reaction was that, since she talked better than others, she ought to be listened to.

Ouida was prolific and wrote by candlelight, propped up in bed at the Langham, scratching a goose quill dipped in violet ink across large sheets of blue paper. When she rose, she would adopt the costume of a character in her current novel, one day a princess, the next a peasant maiden. She accessorised with blooms favoured by her fictional creations.

Above all else, Ouida adored opulence and her extraordinary excesses were funded from the ever-increasing payments she negotiated with eager publishers. Every penny was spent as soon as she got it, often on some fabulous though utterly unserviceable objet d’art. She collected exquisite china and served tea to her guests in priceless Capo di Monte cups, or invited them to wash down platters of uncommon delicacies with the finest vintage wines. Novelist W. H. Mallock recognised this mad extravagance as her attempt to ‘live up to the standards of her heroines’.

In 1871, at the height of her fame, Ouida swapped the Langham for a sprawling villa in Florence; it was falling down around her but it had belonged to a Medici. Returning to London and the Langham for an extended stay in 1886, she accepted an invitation to one of Lady Jane Wilde’s literary ‘Wednesdays’. A fellow guest reported that she

‘spoke in quick disjointed sentences with a peculiar accent, and constantly referred to Oscar – in fact she directed all her conversation to him’.

Wilde invited Ouida to contribute to The Woman’s World, the magazine he edited at the time, and she wrote four articles for him. ‘Have you read my article on War in Oscar Wilde’s magazine?’ she asked a friend. ‘The magazine is so good, its only defect is its title’. In ‘Apropos of a Dinner’, Ouida argued that, although smoking was a ‘silly and injurious habit’, women should be allowed to remain at the dinner table while men indulged; she horrified all of London by doing so herself.

In ‘The Streets of London’, she criticised the ugliness of the city, arguing that a profusion of railings gave ‘almost every house in London the aspect of a menagerie combined with a madhouse’. She despaired of basements, describing them as ‘subterranean places in which nothing but the soul of a blackbeetle can possibly delight’.

In ‘Field-work For Women’, which she illustrated with reproductions of oil paintings she had done in Florence, Ouida postulated that outdoor agricultural labour was far more beneficial to women than unhealthy factory work. In ‘War’, she denounced the evils of combat, which ‘cripples and impoverishes every class of the nation’, and she expressed her vehement opposition to conscription.

Reviewing Ouida’s ‘amazing romance’ Guilderoy in the Pall Mall Gazette, Wilde dubbed her ‘the last of the romantics’. His admiring verdict was ‘though she is rarely true, she is never dull’. Certainly, Ouida was never troubled by pedestrian notions of accuracy. In any case, her fans were always clamouring for another of what Max Beerbohm described as the

‘lurid sequence of books and short stories and essays which she has poured forth so swiftly, with such irresistible élan’.

What appealed to her readers was the unashamed glamour of her situations. That her themes were judged unwholesome only added to her appeal, although her books were often hidden when disapproving visitors called. Seduction, adultery, voyeurism and prostitution were tackled head-on and, although she steered clear of overt homosexuality, her books were undeniably homoerotic.

Ouida popularised the indolent male dandy connoisseur. Her women were strikingly beautiful and aristocratic socialites, loyal to no one but themselves, who spoke in epigrammatic language reminiscent of Wilde’s. While her influence should not be overstated, critics recognised something of her style in his work. In a review of The Picture of Dorian Gray, the St. James’ Gazette opined that while ‘the style was better than Ouida’s popular aesthetic romances the erudition remained nonetheless equal’. Their critic concluded, ‘the grammar is better than Ouida’s – the erudition equal; but in every other respect we prefer the talented lady’.

Writing in McBride’s Magazine, Julian Hawthorne, journalist son of Nathaniel, claimed:

Mr. Wilde‘s writing has what is called “colour,” – the quality that forms the main-stay of many of Ouida‘s works, – and it appears in the sensuous descriptions of nature and of the decorations and environments of the artistic life.

Ouida’s short play Afternoon, which was published in 1883, introduced ‘Aldred Dorian’, a collector of beautiful objects and a painter of portraits.

When Wilde sent Ouida a copy of Dorian Gray, she declared: ‘I do understand it’. She had returned to Florence by then, having spent more recklessly than ever during her four month stay in London. While there, she had ordered a new wardrobe from The House of Worth and lavished £200 a week on ‘turning her sitting room in the Langham Hotel into a glade of the most expensive flowers’. When W. H. Mallock hosted a luncheon for her in the Bachelors’ Club, she arrived:

…trimmed with the most exuberant furs, which, when they were removed, revealed a costume of primrose-colour—a costume so artfully cut that, the moment she sat down, all eyes were dazzled by the sparkling of her small protruded shoes.

Such extravagance emptied Ouida’s purse, obliging her to seek assistance from friends. In The Real Oscar Wilde, Robert Sherard claimed that it was Wilde who ‘furnished her with sufficient money to pay the Margaret Street people [where she had modest lodgings], and rescue her luggage, and then to return to Florence’.

In Italy, Ouida fared no better. When the lucrative publishing deals dried up, she swapped her villa for an ever-degenerating series of lodging houses from which she was sometimes evicted by force. News of her plight reached fellow novelist Marie Corelli, who persuaded the editor of the Daily Mail to establish a fund to assist her. On reading this, Ouida became incandescent with rage and demanded that he never print her name again.

When friends petitioned the Prime Minister to grant her a Civil List Pension of £150 a year, she railed that this sum was ‘only fit for superannuated butlers’. On 25 January 1908, Ouida, aged seventy and a shadow of her former self, died of pneumonia. She was living in a modest lodging house in Viareggio at the time. Later that year, Macmillan published her final novel, Helianthus in its incomplete form. She is largely forgotten today.

Wilde’s Women: How Oscar Wilde Was Shaped by the Women he Knew was published by Duckworth Overlook on 16 October 2015. Follow me on twitter @EleanorFitz

January 22, 2016

Oscar & Constance: a love story

On this day in 1884, Oscar Wilde wrote a letter to his good friend Thomas Waldo Story – sculptor, art critic, poet and literary editor – from the Royal Victoria Hotel in Sheffield, where he was lecturing at the time.

In this letter, he described in glowing and playful terms the young woman to whom he had become engaged weeks earlier:

Her name is Constance and she is quite young, very grave, and mystical, with wonderful eyes, and dark brown coils of hair: quite perfect except that she does not think Jimmy [Whistler] the only painter that ever really existed: she would like to bring Titian or somebody in by the back door: however, she knows I am the greatest poet, so in literature she is all right: and I have explained to her that you are the greatest sculptor: art instruction cannot go further.

We are, of course, desperately in love.

Constance Lloyd before her marriage to Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde married Constance Lloyd on May 29, 1884. This letter is reproduced in Holland, Merlin and Rupert Hart-Davis (Eds). The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde (London, Fourth Estate, 2000), pp.225-6

January 20, 2016

Was Yvette Guilbert “The Ugliest Woman in The World”?

Today is the anniversary of the birth of Yvette Guilbert (1865-1944), French cabaret singer and actress of La Belle Époque. Artist Henri de Toulouse Lautrec was captivated by her and she modeled for him many times, although what emerged was not always a flattering likeness.

Yvette Guilbert Salue le Public (1894)

Perhaps Toulouse Lautrec was faithful in his rendering of Guilbert’s unconventional appearance. Rumour has it that she exchanged the following words with Oscar Wilde at the studio of Wilde’s friend, artist Prince Pierre Troubetzkoy:

Ne suis-je pas, Monsieur, la femme la plus laide de France ? (Am I not, Sir, the ugliest woman in France?)

Guilbert asked.

To which Wilde replied:

Du monde, Madame, du monde (The world, Madame, the world).

It’s a great story but I’m not certain I believe it since Wilde was generally far more gallant than that. Although I decided not to include this peripheral figure in Wilde’s Women, there is evidence that she met Wilde.This pencil drawing, dated 1898, by Catalan artist Ricard Opisso i Sala (1880-1966), shows Toulouse Lautrec, Wilde and Guilbert sitting together at Le Moulin de la Galette, Montmartre, Paris.

They are together in death since both are buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

The main source for this article can be found on the http://www.oscholars.com website here.

January 19, 2016

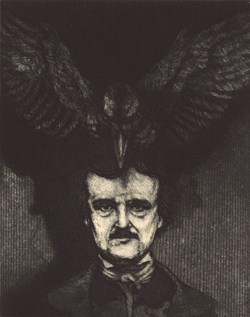

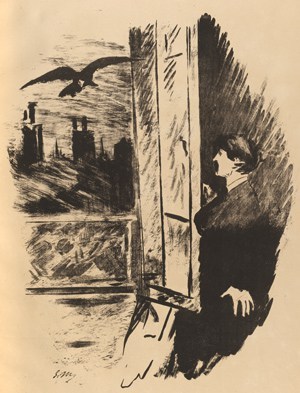

The Raven and the Revolutionaries

Today marks the anniversary of the birth of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), best known for his chilling yet utterly compelling tales of the macabre. It was his supernatural narrative poem, The Raven that brought him to the attention of an admiring American public when it appeared in the New York Mirror on February 8, 1845; it had been published in the American Review the previous month under the pseudonym ‘Quarles’. Within weeks, The Raven had been reprinted a dozen times and had spawned several parodies.

From Nevermore: The Edgar Allan Poe Collection of Susan Jaffe Tane in Cornell University

This hugely positive response ensured that Poe achieved fame in his lifetime, and his literary legacy lingers to this day. References to The Raven in popular culture include appearances in: Hubert Selby Jr’s 1964 novel Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964) when Georgette, the lead character in ‘The Queen is Dead’, reads the poem aloud; in Joan Aiken’s novel Arabel’s Raven (1972); in Stephen King’s novel Insomnia (1994); in the 1989 film Batman when Jack Nicholson’s Joker asks Kim Basinger’s Vicky Vale to ‘Take thy beak from out my heart’; and in The Simpsons ‘Treehouse of Horror’ when Lisa reads the poem aloud to Bart and Maggie.

The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror

Yet, Poe might never have achieved such prominence without the help of Anne Lynch Botta (1815-1891), a prominent patron of the arts whose literary gatherings, described as a ‘bibliophile’s dream’, were attended by every major poet, artist and musician of her day, among them Emerson, Irving, Trollope, Thackeray, Horace Greeley, Fanny Osgood and Margaret Fuller. Lynch Botta introduced Poe, virtually unknown in New York, to her influential circle and encouraged him to read early versions of The Raven aloud.

Illustration by Edouard Manet

Although a published poet herself, friends confirmed: ‘It was not so much what Mrs. Botta did for literature with her own pen, as what she helped others to do, that will make her name a part of the literary history of the country’. In The Literati of New York – No. V, Poe wrote of her:

In character Miss Lynch is enthusiastic, chivalric, self-sacrificing, “equal to any Fate,” capable of even martyrdom in whatever should seem to her a holy cause — a most exemplary daughter. She has her hobbies, however, (of which a very indefinite idea of “duty” is one,) and is, of course, readily imposed upon by any artful person who perceives and takes advantage of this most amiable failing.

He described her appearance too:

In person she is rather above the usual height, somewhat slender, with dark hair and eyes — the whole countenance at times full of intelligent expression. Her demeanor is dignified, graceful, and noticeable for repose. She goes much into literary society.

Anne Lynch Botta

While his literary talent also emerged in time, it may have been the revolutionary credentials of his formidable mother that attracted Lynch Botta to young Oscar Wilde, who she entertained during the early weeks of his 1882 tour of America. Her own father, a revolutionary Dubliner named Patrick Lynch, had been first imprisoned, then deported from Ireland, aged eighteen, after the failed rising of 1798. By coincidence, Lady Jane Wilde, as she had become by then, presided over a hugely popular literary salon of her own in London, where she had resettled after the death of her husband, Sir William Wilde. Both women are included in my book, Wilde’s Women.

Lady Jane Wilde

January 17, 2016

New Reviews of Wilde’s Women

I’m absolutely thrilled that Wilde’s Women has been reviewed in The Guardian newspaper by the wonderful Simon Callow, acclaimed actor and a distinguished biographer in his own right.

Also thrilling is the lovely, positive review Wilde’s Women received in iconic magazine, The Lady (THE place to advertise for a governess or housekeeper should you require one).

Additional reviews can be found below:

The Irish Times asked renowned and respected Wilde scholar Dr. Eibhear Walshe to review Wilde’s Women. There’s a link to the review here.

Wilde’s Women has also been reviewed positively by The Independent here and here, by Kirkus and by We Love This Book (book of the week) among others. There is a round-up of review highlights on my author page on my agent’s website: http://www.andrewlownie.co.uk.

January 14, 2016

Wilde as Literary Magpie

The Public Domain Review has a great article On Oscar Wilde and Plagiarism, which he engaged in unashamedly. My favourite quote on the subject, which I include in Wilde’s Women, comes from bestselling Victorian novelist Ouida; Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was often compared to her work:

“I have written three comedies in one year,’ he [Wilde] said to a friend of mine, and my friend replied: ‘A great exercise of memory!”

Love her!!

I’ll write a post about her soon…

Bestselling Victorian Novelist Ouida