Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 9

April 3, 2016

Washington Irving & Oscar Wilde: A Very Tenuous Connection

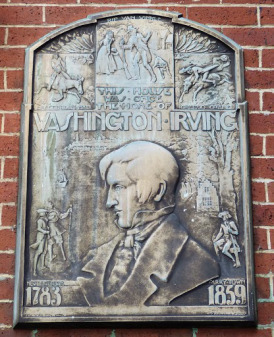

What links American author, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat Washington Irving, born on this day (3 April) in 1783, with Oscar Wilde, who was born almost eight decades later?

Washington Irving, author of ‘Rip Van Winkle and ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’

One very tenuous link lies in a case of mistaken identity – of a property rather than a person. In 1844, an ornate three-story Italianate-style house was erected at 122 East 17th Street in New York; it also had the designation 49 Irving Place.

49 Irving Place. Photo by Alice Lum

Beginning in 1831, during Irving’s lifetime, politician and developer Samuel Bulkley Ruggles laid out Union Square, Irving Place and Gramercy Park, as well as Lexington Avenue, on property he owned. In 1833, he named Irving Place in honour of the celebrated author, who never lived there.

Always a desirable address, in the early 1890s 49 Irving Place was rented to actress-turned-interior-designer Elsie de Wolfe and her partner, Elisabeth Marbury, an innovative literary and theatrical agent who represented Wilde in America. The women lived there for almost two decades and the 1905 census records Marbury as head of the household with de Wolfe as her ‘partner’.

Elizabeth Marbury & Elsie de Wolfe

Marbury and de Wolfe established a hugely successful salon in their lovely home and it seems likely that it was de Wolfe, always a keen self publicist, who started the rumour of a connection with Irving. The first mention of the property having been his home at one time appeared in The New York Times in 1897, in an article describing the house and praising the ‘wonderful talents’ of Elsie de Wolfe.

This anonymous article quoted Irving at great length, apparently waxing lyrical about the design and layout of his ‘former home’. Although without any foundation, over time this same connection was made in dozens of books, newspapers and magazine articles, and became widely accepted.

In one instance, The Times noted:

‘Teas at the home of Miss Marbury and Miss De Wolfe, in the old Washington Irving residence, at Seventeenth Street and Irving Place, are regular Sunday afternoon affairs of importance in the literary and dramatic world during the height of the season.’

Marbury and de Wolfe left the house in 1911, and in 1927 it was acquired by the National Patriotic Builders of America, who wished to convert it to a museum and preserve it as a shrine to Irving. A subsequent fundraising effort hit controversy when descendants of Irving insisted that he had never even entered the building, let alone lived there. Nevertheless, in 1834 a plaque was erected to commemorate the false connection.

Photo by Alice Lum

As to Oscar Wilde, Marbury first met him during his 1882 tour of America at the home of a Professor Doremus. He was holding a cup of tea at the time and endeared himself by offering it to her. Ever the publicist, she realised that his eccentric appearance was:

‘well conceived and of value in stimulating curiosity and in providing copy for the press’.

As she got to know him better, Marbury summed Wilde up perfectly, observing:

‘His wit scintillated incessantly. His joy in the phrases he compiled was always evident though never offensive’.

In My Crystal Ball, her somewhat fanciful memoir, Marbury described Wilde holding court at his Tite Street home, thinking aloud the plots of his plays:

‘I remember one terrible tragedy, brutally conceived, which revolved around a most revolting theme,’

she wrote.

‘It took me many days before I could prove to him that despite the dramatic value of the story that the managers and public would never tolerate the motive’.

In 1898, Marbury was charged with selling The Ballad of Reading Gaol in America. Although tears rolled down her cheeks as she read it, she admitted to Leonard Smithers:

‘Nobody here seems to feel any interest in the poem’.

She finally secured $250 from the New York World.

In her memoir, Marbury claimed to have encountered Wilde in Paris towards the end of his life. He was, she wrote, ‘unkempt, forlorn and penniless’, living in ‘a wretched room in the attic of a squalid little hotel’.

Whatever the general accuracy of My Crystal Ball, Marbury was effusive in her praise for Wilde’s talent, considering De Profundis to be his ‘masterpiece and a rich contribution to the treasure house of English literature’. As it was ‘conceived and written in the depths,’ she wrote, ‘[i]t was given to the world as Oscar’s last message to save others from the depths’.

Undoubtedly, she qualifies as one of Wilde’s Women.

For more information see:

New York Times, 13 March 1994, ‘The ‘Washington Irving’ House; Why the Legend of Irving Place Is but a Myth’

and

Elizabeth Marbury, My Crystal Ball (New York, Boni & Liveright, 1923)

March 30, 2016

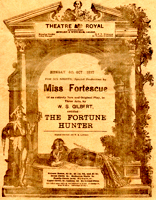

May Fortescue: ‘not simply a pretty, brainless doll’

When Irish writer Katharine Tynan attended Lady Jane Wilde’s celebrated salon for the first time one of the people she met there was actress May Fortescue, a member of the original cast of Patience, the comic operetta by Gilbert and Sullivan in which Oscar was satirised as Reginald Bunthorne, a foppish poet.

May Fortescue

Born Emily Finney, the daughter of a Peckham coal merchant, May Fortescue was prominent in the gossip columns of the day since she had just announced her intention of establishing her own theatre company using the £10,000 awarded to her in a breach of promise action.

This was appropriately mischievous since she blamed Hugh McCalmont Cairns, 1st Earl Cairns, Lord Chancellor and a dour Ulsterman, for persuading Arthur William Cairns, Lord Garmoyle, his son and her erstwhile fiancé, to end their engagement in January 1884 on the grounds that he considered the theatre to be ‘the ante-chamber of hell’. This despite the fact that she had given up the stage and persuaded her sister to do likewise.

When Frank Harris, editor of the Evening News, published May’s account of the breakup under the headline ‘Beauty and the Peer’, the circulation of his paper doubled.[i] Interestingly, American-born artist James McNeill Whistler had recently hosted an engagement luncheon for Oscar, Constance and the erstwhile couple.

May, who had taken up acting to support her family after her father’s business failed, was highly intelligent and exceptionally well educated for a women of her time. In a letter to Garmoyle, written in response to his ending of their engagement, she assured him that she was ‘not simply a pretty, brainless doll’.[2] This proved to be the case. Her theatre company was a success and toured for years, often performing the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. May Fortescue acted for four decades after her broken engagement and lived to the age of 88.

Although not qualified to be one of Wilde’s Women, she was admirable and formidable nonetheless.

[i] Frank Harris, My Life and Loves Volume II, Privately printed, p.338

[2] Martha Vicinus, A Widening Sphere: Changing Roles of Victorian Women, Routledge Revivals, p.109

March 25, 2016

Wilde, Roman Catholicism & ‘Easter Day’

‘I am not a Catholic,’ quipped Oscar Wilde. ‘I am simply a violent Papist.’ Although raised a Protestant, Wilde’s flirtation with Catholicism waxed and waned throughout his life and culminated in his famous deathbed conversion. This fascination, in keeping with his determination to be recognised as a poet, appears to have been inherited from his formidable mother, Jane, the foremost of Wilde’s Women. In 1905 Father Lawrence Fox, an elderly priest, insisted that, five decades earlier, he had baptised a young Oscar, aged about four, and his brother Willie, aged six or seven, into the Catholic faith at Jane’s instance.

Several of Wilde’s earliest poems explore distinctly Catholic themes. As an undergraduate at Oxford University he traveled to Rome where his great friend David Hunter Blair, himself a convert to Catholicism, had organised a private audience with Pope Pius IX. Wilde was much affected by this meeting and it inspired further poetry. Yet, in ‘Easter Day’, published in his collection Poems (1881), Wilde juxtaposes the splendor of the papacy with the humble origins of the faith in a way that appears critical of church authorities who had, to use an Irish phrase, lost the run of themselves.

Pope Pius IX

EASTER DAY

The silver trumpets rang across the Dome:

The people knelt upon the ground with awe:

And borne upon the necks of men I saw,

Like some great God, the Holy Lord of Rome.

Priest-like, he wore a robe more white than foam,

And, king-like, swathed himself in royal red,

Three crowns of gold rose high upon his head:

In splendor and in light the Pope passed home.

My heart stole back across wide wastes of years

To One who wandered by a lonely sea,

And sought in vain for any place of rest:

“Foxes have holes, and every bird its nest,

I, only I, must wander wearily,

And bruise My feet, and drink wine salt with tears.”

Notwithstanding this, on Easter Day 1900, months before his death, Wilde positioned himself in the front row among the pilgrims at the Vatican to receive a blessing from Pope Leo XIII. He told his friend Robbie Ross:

‘When I saw the old white Pontiff, successor of the Apostles and Father of Christendom pass, carried high above the throng, and in passing turn and bless me where I knelt, I felt my sickness of body and soul fall from me like a worn garment, and I was made whole.’

Like everything else in Wilde’s life, his relationship with the Catholic Church was complex but compelling. Understandable considering he believed that Roman Catholicism was:

‘for saints and sinners alone – for respectable people, the Anglican Church will do’.

March 18, 2016

The Day Willie Wilde Got Engaged to a Teenage Lesbian

One of the more unusual episodes in Wilde’s Women concerns Oscar Wilde’s brother, Willie. In 1879, Willie Wilde left Dublin for London, where he hoped to make a good living as a journalist. A handsome man endowed with considerable charm, he also planned to marry well, and he lost no time in putting this plan into effect.

Willie Wilde

During the crossing from Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) to Holyhead, Willie bumped into Ethel Smyth, the teenage daughter of a Major-General in the Royal Artillery. The two had spent the previous day playing lawn tennis at the home of mutual friends in Bray, County Wicklow, where they had, by her account:

…discussed poetry, the arts, and more particularly philosophy, in remoter parts of the garden.

Ethel Smyth with her dog ‘Marco’

During the boat-trip, they got on famously, particularly when Willie showed great good humour in taking a nasty bout of seasickness on Ethel’s part in his stride. He proposed to her during the train journey from Holyhead to Euston and Ethel accepted with alacrity.

A traditional Irish Claddagh ring

Three weeks later, the engagement was off. Although Willie graciously allowed Ethel to keep the Claddagh ring he had bought her, she lost it a year or two later

…while separating two dogs who were fighting in deep snow in the heather.

Decades later, in old age, Dame Ethel Smyth OBE, celebrated composer, author, campaigner for women’s suffrage, and confirmed lesbian, confessed:

I was no more in love with [Willie] than I was with the engine-driver!

Source:

Dame Ethel Smyth. 1946. Impressions that Remained. New York, Alfred A. Knopf

March 16, 2016

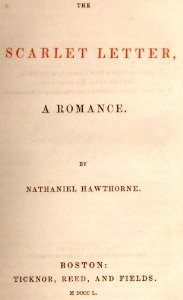

Jane Wilde, William Rowan Hamilton & The Scarlet Letter

On this day (16 March) in 1850, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter was published in Boston by Ticknor, Reed and Fields. One early admirer was Lady Jane Wilde, who recommended it to her great friend, astronomer and mathematician William Rowan Hamilton five years before it was published in London on the basis that it had cost her ‘three nights sleep’. She was in the habit of asking American friends to send her copies of works that interested her and read Walt Whitman’s newly published Leaves of Grass (1855) to her son Oscar when he was a tiny child.

Decades later, in 1882, Oscar made a point of visiting Whitman during his extended tour of America. He also invoked The Scarlet Letter when writing A Woman of No Importance.

For more on Jane Wilde’s great friendship with William Rowan Hamilton read Chapter 3 of Wilde’s Women.

For more on William Rowan Hamilton’s great friendship with poet William Wordsworth read my blog post for The Romanticism Blog here.

Living & Dying in the Shadow of Oscar Wilde

Imagine if you were (and perhaps you are) a charming, erudite man with a talent for writing. Behind you is a glittering academic record and before you lies a promising future earning a good living by means of your pen. The only impediment? Your little brother is Oscar Wilde.

Willie Wilde

Poor Willie Wilde was overshadowed by Oscar from an early age and it didn’t sit easy with him. When Oscar’s fame was at its height, Willie could be found drinking, gossiping and reciting parodies of his brother’s poems in the fashionable Lotos Club in New York: ‘You know, Oscar had a fat, potato-choked sort of voice,’ one fellow Lotos Club member recalled, ‘and to hear Willie counterfeit that voice and recite parodies of his brother’s poetry was a rare treat.’

He certainly took to socialising with gusto. Another member of the Lotos Club remembered him as ‘the most thoroughgoing night owl that ever lived,’ and confirmed that he ‘positively hated daylight’.

In his memoir, Pitcher in Paradise, Willie’s contemporary Arthur M. Binstead described his friend as ‘the personification of good nature and irresponsibility’. To illustrate this, Binstead reproduced Willie’s amusing description of his typical working day in London, which began when he popped into his editor at noon to suggest an idea for a feature; ‘the anniversary of the penny postage stamp’ for instance. Then:

I bow myself out. I may then eat a few oysters and drink half a bottle of Chablis at Sweeting’s, or, alternatively partake of a light lunch…I then stroll towards the Park. I bow to the fashionables. I am seen along incomparable Piccadilly. It is grand. But meantime I am thinking only of that penny postage stamp.

Afterwards, Willie would repair to his club to spend two hours scribbling furiously before dispatching his leader to the Daily Telegraph offices and heading out, arm in arm with a friend, to enjoy:

…that paradise of cigar-ashes, bottles, corks, ballet, and those countless circumstances of gaiety and relaxation, known only to those who are indwellers in the magic circles of London’s literary Bohemia. [ii]

Willie comforts Oscar after the failure of his first play, Vera (Alfred Bryan, 1883)

Inevitably, his prodigious appetite for alcohol caught up with him. On 13 March 1899, Willie Wilde, aged forty-six, succumbed to complications related to alcoholism. When Robbie Ross wrote to inform Oscar of his brother’s death, he replied:

I suppose it had been expected for some time. I am very sorry for his wife, who, I suppose, has little left to live on. Between him and me there had been, as you know, wide chasms for many years. Requiescat in Pace. [iii]

For far more on Willie Wilde and his relationship with his brother Oscar why not read my book Wilde’s Women.

Sources:

[i] ‘Wilde and Willie’ by Nancy Johnson (archivist) in News and Notes from the Lotos Club, January 2011

[ii] Arthur Morris Binstead, Pitcher in Paradise: Some Random Reminiscences, Sporting and Otherwise (London, Sands, 1903)

[iii] Letter to Robbie Ross, March 1899,Complete Letters, p.1130

March 14, 2016

John Lane, Oscar Wilde & The Yellow Book

Today (14 March) marks the anniversary of the birth of publisher John Lane (1854-1925), co-founder with Elkin Mathews, of The Bodley Head publishing house. In 1894, The Bodley Head began publishing The Yellow Book, a Decadent hardback quarterly literary periodical that boasted an illustrious list of contributors and promoted New Woman writers.

John Lane

Not everyone was a fan. Shortly after the first issue appeared, Oscar Wilde sent a letter to Bosie: ‘The Yellow Book has appeared,’ he wrote. ‘It is dull and loathsome, a great failure. I am so glad’. Later, he expressed his displeasure to Ada Leverson: ‘Have you seen The Yellow Book?’ he inquired. ‘It is horrid and not yellow at all’. Leverson was surely more enthusiastic, since she contributed several short stories, one of which, ‘Suggestion’ is reminiscent of The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Ironically, although he detested The Yellow Book and was never invited to contribute to it, a misinterpreted line from Dorian Gray led to a spurious link between Wilde and The Yellow Book. The line in question is: ‘His eyes fell on the Yellow Book that Lord Henry had sent him’. In fact, the book is fictitious and resembles Joris-Karl Huysman’s À rebours, a favourite of Wilde’s, more than any other.

When Lane arrived in New York in April 1895, he was confronted with newspaper headlines announcing: ‘Arrest of Oscar Wilde, Yellow Book under his arm’. Although the book in question has been identified by Margaret D. Stetz and Mark Samuels Lasner as a yellow-bound copy of Aphrodite by Pierre Louÿs, Lane realised the implications and despaired: ‘It killed The Yellow Book and it nearly killed me’, he claimed.

Without delay, Lane telegraphed his office manager and instructed him to remove Wilde’s books from sale. By then, several authors were threatening to boycott The Bodley Head, which employed Edward Shelley, a young clerk who had testified to being involved in a sexual relationship with Oscar. On 5 April 1895, The Bodley Head premises at Vigo Street were attacked by a stone-wielding mob.

When Lane removed Aubrey Beardsley, who was associated with Wilde, as Art Editor of The Yellow Book, W.B. Yeats claimed this was done at the insistence of ‘a popular novelist, a woman who had great influence among the most conventional part of the British public’. This was surely Mrs. Humphry Ward, who had encouraged poet William Watson to write to Lane and threaten to change publisher unless The Yellow Book was discontinued. When poet Alice Meynell’s husband, Wilfred, applied similar pressure,Volume 5 was halted mid-production , although it did appear a fortnight later and the publication limped along for another two years.

Lane, a pioneer of New Women’s writing, also published the contentious Keynotes, which took its name from the first in the series, a collection of musings by Mary Chavelita Dunne, who wrote as George Egerton. Dunne, a contributor to The Yellow Book, was closely associated with the Decadent movement. Her Keynotes (1893) caused a sensation by tackling controversial themes including female sexuality, sexual freedom, alcoholism and suicide.

‘George Egerton’

The daughter of an Irish army officer, Dunne described herself as ‘intensely Irish’. By echoing Wilde’s style and quoting him in an epigram to her story ‘A Little Gray Glove’, she reinforced his association with New Women’s writing. Several passages in her story ‘A Cross Line’ imagine a dance in a ‘dream of motion’, and take much from Salomé:

She can see herself with parted lips and panting, rounded breasts, and a dancing devil in each glowing eye, sway voluptuously to the wild music that rises, now slow, now fast, now deliriously wild, seductive, intoxicating, with a human note of passion in its strain.

Dunne loathed the duplicity of Victorian society, which she summed up sardonically in a letter to her father: ‘sin as you please but don’t be found out it’s all right so long as you don’t shock us by letting us know’. Her writing was parodied in Punch as ‘She-notes’ by Borgia Smudgiton, and she was rechristened ‘Dona Quixote’, a sure indication of the anxiety she provoked with her challenging themes.

Although Dunne wrote four more short story collections: Discords (1894), Symphonies (1897), Fantasias (1898), and Flies in Amber (1905); one epistolary collection: Rosa Amorosa (1901); one novel: The Wheel of God (1898); and several plays, most notably His Wife’s Family (1907), Backsliders (1910) and Camilla States Her Case (1925); she never replicated the success of Keynotes. As a supporter of Wilde’s and a writer who emulated his style, she qualifies as one of Wilde’s Women.

March 10, 2016

When Dolly Wilde Met Zelda Fitzgerald

It’s not widely known that Oscar Wilde’s niece Dorothy, always known as Dolly was written into then out of Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald after she made a drunken pass at his wife, Zelda one night in Paris.

Zelda Fitzgerald

Dolly Wilde was born in 1895 into chaos and poverty to a father lost to alcohol and a mother whose inability to cope led her to abandon her infant daughter in what she described as a ‘country convent’. From the day of her birth, just three months after the imprisonment of her Uncle Oscar, her life was governed by turmoil and impulsiveness.

In adulthood, Dolly was so outrageous that had she been fictional she would have lacked credibility. As a teenager, she ran away to war torn France, where she drove an ambulance and developed a taste for fast cars and exotic women. An incorrigible womaniser, Dolly specialised in ‘emergency seductions’ and went through a string of lovers. When, much to Scott’s annoyance, she made a pass at Zelda, he captured her in an unflattering cameo in Tender is the Night as incorrigible lesbian seductress Vivien Taube, but he deleted the passage from the published version.

Here’s an excerpt:

An hour later he came out of somewhere to a taxi whither they had preceded him and found Wanda limp and drunk in Miss Taube’s arms.

“What’s the idea?” he demanded furiously.

Miss Taube smiled at him. Wanda opened her eyes sleepily and said:

“Hello.” .

“What’s all this business?” he repeated.

“I love Wanda,” said Miss Taube.

“Vivian is a nice girl,” said Wanda. “Come sit back here with us.”

“Why can’t you get out of the taxicab and go home with your friends,” said Francis harshly to Miss Taube. “You know you have no business to do this. She’s tight.”

“I love Wanda,” repeated Miss Taube good-naturedly.

“I don’t care. Please get out.”

In answer Wanda drew the girl close to her again, whereupon in a spasm of fury Francis opened the door, took her by the arm and before the girl understood his purpose deposited her in a sitting position on the curb.

“This is perfectly outrageous!” she cried.

“I should say it is!” he agreed, his voice trembling. A chasseur and several by-standers hurried up; Francis spoke to the driver and got into the cab quickly. The incident had wakened Wanda.

“Why did you do that?” she demanded. “I’ll have to go back.”

“Do you realize what she was doing?”

“Vivian’s a nice girl.”

“Vivian’s a——”

Although Dolly never met her famous uncle, her pale, elongated face, remarkable blue-grey eyes, shock of dark hair and affected pose, conjured him up for all who met her. She inherited too his ‘clear, low, musical voice’, insatiable appetite for cigarettes and inability to regulate her chaotic finances.While her friends nicknamed her Oscaria, Dolly herself declared: ‘I am more like Oscar than Oscar himself’. In her ‘Letter from Paris’ column in July 1930, Janet Flanner, Paris correspondent of The New Yorker, described Dolly attending a bal-masqué dressed as Oscar, ‘looking both important and earnest’. When H.G. Wells bumped into her at the Paris PEN Club, he declared himself ‘delighted to meet at last a feminine Wilde’.

Dolly Wilde

Her end was as tragic as her uncle’s.

You can read more about Dolly Wilde in Joan Schenkar’s biography, Truly Wilde and in my Wilde’s Women.

March 7, 2016

Was Oscar Wilde a Feminist?

On the eve of International Women’s Day, I thought I’d address a question I am asked frequently: ‘was Oscar Wilde a feminist?’ I could write far more but this is just a short look at his views on puritanical women and their opposition to the sexual double standard. You’ll have to read my book Wilde’s Women to learn more.

Although Wilde believed in equality of opportunity for everyone, men and women alike, a sentiment that resonates with feminist thinking today, he was, first and foremost, an individualist who embraced self-determination. Certainly, he supported the efforts of many women of his acquaintance in their efforts to access the opportunities afforded to men, and he campaigned in The Women’s World for voting rights, education, and the opening of the professions to women. Yet, he disagreed fundamentally with those first wave feminists who believed that the eradication of the sexual double standard could best be achieved by holding men to the same strict moral code that had traditionally been imposed upon women.

Wilde’s opposition to this approach is best exemplified perhaps in the character of Hester Worsley, a puritanical young American who appears in his play A Woman of No Importance. Hester sees herself as a defender of women: ‘you are unjust to women in England,’ she declares, ‘and till you count what is a shame in a woman to be an infamy in a man, you will always be unjust’. By condemning the system of ‘one law for men and another for women,’ she is echoing feminist reformer Josephine Butler.

Josephine Butler

Hester’s declaration that ‘immoral men are welcomed in the highest society and the best company’ parodies Butler’s assertion that dissolute men were ‘received in society and entrusted with moral and social responsibilities, while the lapse of a woman of the humbler class…is made the portal for her of a life of misery and shame’. Laudable as this seems, Oscar was utterly opposed to such thinking. When interviewed about A Woman of No Importance, he contended:

Several plays have been written lately that deal with the monstrous injustice of the social code of morality at the present time. It is indeed a burning shame that there should be one law for men and another law for women. I think…I think there should be no law for anybody.

This was not new thinking on Oscar’s part. Describing the doctrine of ‘sheer individualism’ in a speech he gave to the Royal General Theatrical Fund on 26 May 1892, he insisted: ‘It is not for anyone to censure what anyone else does, and everyone should go his own way, to whatever place he chooses, in exactly the way that he chooses’.

He certainly followed his own advice.

Quoted in Joseph Bristow, Wilde Writings: Contextual Conditions (Toronto; Buffalo: Published by the University of Toronto Press in association with the UCLA Center for Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Studies and the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, 2003), p.135

Gilbert Burgess, ‘A Talk with Mr. Oscar Wilde’, The Sketch, 9 January 1895, quoted in Mason, Bibliography, p.440

March 2, 2016

THE ADVISABILITY OF NOT BEING BROUGHT UP IN A HANDBAG.

On 2 March 1895, Punch magazine published a satirical parody of Oscar Wilde’s play, The Importance of Being Earnest, which had opened to huge acclaim at the St. James’s Theatre a fortnight earlier. Ada Leverson was the author of THE ADVISABILITY OF NOT BEING BROUGHT UP IN A HANDBAG, which she subtitled ‘A Trivial Tragedy for Wonderful People’. A close friend to Wilde, she had recorded her impressions of opening night. Her pitch-perfect parodies of his work are affectionate yet hilarious and this was to be the last of them.

Ada Leverson

THE ADVISABILITY OF NOT BEING BROUGHT UP IN A HANDBAG: A Trivial Tragedy for Wonderful People

(Fragment found between the St. James’s and Haymarket Theatres).

Aunt Augusta (an Aunt).

Cousin Cicely (a Ward).

Algy (a Flutterpate).

Dorian (a Button-hole).

The Duke of Berwick.

Time—The other day. The Scene is in a garden, and begins and ends with relations.

Algy (eating cucumber-sandwiches). Do you know, Aunt Augusta, I am afraid I shall not be able to come to your dinner to-night, after all. My friend Bunbury has had a relapse, and my place is by his side.

Aunt Augusta (drinking tea). Really, Algy! It will put my table out dreadfully. And who will arrange my music?

Dorian. I will arrange your music, Aunt Augusta. I know all about music. I have an extraordinary collection of musical instruments. I give curious concerts every Wednesday in a long latticed room, where wild gipsies tear mad music from little zithers, and I have brown Algerians who beat monotonously upon copper drums. Besides, I have set myself to music. And it has not marred me. I am still the same. More so, if anything.

Cicely. Shall you like dining at Willis’s with Mr. Dorian to-night, Cousin Algy?

Algy (evasively). It’s much nicer being here with you, Cousin Cicely.

Aunt Augusta. Sweet child! I see distinct social probabilities in her profile. Mr. Dorian has a beautiful nature. And it is such a blessing to think that he was not brought up in a handbag, like so many young men of the present day.

Algy. It is such a blessing, Aunt Augusta, that a woman always grows exactly like her aunt. It is such a curse that a man never grows exactly like his uncle. It is the greatest tragedy of modern life.

Dorian. To be really modern one should have no soul. To be really mediæval one should have no cigarettes. To be really Greek——

[The Duke of Berwick rises in a marked manner, and leaves the garden.

Cicely (writes in her diary, and then reads aloud dreamily). “The Duke of Berwick rose in a marked manner, and left the garden. The weather continues charming.” …