Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 5

November 30, 2016

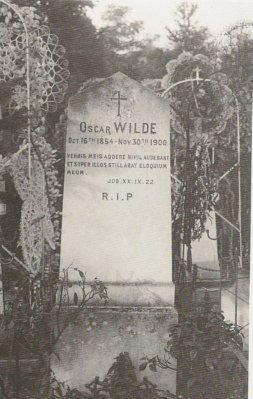

Oscar Wilde: October 16 1854 – November 30 1900

As his life drew to a close, Oscar’s general health was poor. For much of his adult life, he had suffered from intermittent deafness and infections in his right ear, a condition that had flared up in prison but was inadequately treated. In September 1900, he fell ill once again, to the extent that it was necessary for his right ear was operated on in his hotel room. Although the procedure appeared to have been effective, by mid-November he had suffered a relapse and was confined to bed.

During the final weeks of his life, Oscar was nursed lovingly by his great friends Robbie Ross and Reggie Turner. On 29 November, Ross, a convert to Catholicism since 1894, sent for Father Cuthbert Dunne, a priest attached to the Passionist Church of St. Joseph’s in Paris. Although incapable of speech at that point, Oscar was conditionally baptised into the Catholic faith; Ross assured Ada Leverson that was in accordance with her friend’s long-held wishes.

Early on the morning of 30 November, a change came over Oscar and his breathing became laboured. Shortly before two o’clock in the afternoon, he heaved a great sigh and breathed his last. Ross laid out his friend’s body and found two Franciscan nuns to watch over him while he informed the authorities of the death of Oscar Wilde.

Wilde’s first grave in Bagneux

NOTE:In their paper ‘Oscar Wilde’s terminal illness: reappraisal after a century’, Ashley H Robins and Sean L Sellars concluded, based on medical evidence, that Oscar Wilde died of meningoencephalitis secondary to chronic right middle-ear disease. (The Lancet, Vol 356, November 25, 2000, pp.1841-1843)

November 29, 2016

Oscar ‘drew off part of the crowd which had formed around Miss Alcott’

Novelist and campaigner Louisa May Alcott was born on 29 November, 1832 in Pennsylvania, the second of four girls. She is best remembered as the author of Little Women. As she makes a brief appearance in Wilde’s Women, I’ve posted an extract in her honour.

Louisa May Alcott

Oscar’s final engagement that evening was a reception hosted by English-born Jane Cunningham Croly in honour of author Louisa May Alcott, who was nearing the end of her career and her life. Croly, better known by her pen-name ‘Jennie June’, was an exceptionally useful supporter to cultivate. Credited with pioneering and syndicating the ‘woman’s column’, she ran the women’s department at the New York World for ten years and was chief staff writer at Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions, later renamed Demorest’s Monthly Magazine. As ‘Jennie June’, she wrote ‘Gossip with and for Women’ for the New York Dispatch and ‘Parlour and Sidewalk Gossip’ for Noah’s Sunday Times. The sole breadwinner in her family, she juggled the responsibilities of motherhood and journalism by spending mornings at home before heading into the office at noon and working steadily until after midnight. Sunday nights were reserved for entertaining New York’s intellectual and artistic elite.

A passionate believer in networking for women, Croly founded the Women’s Parliament in 1856. She responded to the exclusion of women journalists, herself included, from an honorary dinner organised for Charles Dickens by the New York Press Club by founding Sorosis, America’s first professional woman’s club. She also established the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the New York Women’s Press Club. The elite members of her own New York Women’s Club campaigned for education, improved working conditions and better healthcare for women. An uncompromising realist, she once wrote:

Girls are none the worse for being a little wild, a little startling to very proper norms, and much less likely, in that case, to spend their time gasping over sentimental novels, and imagining that every whiskered specimen they see is their hero.1

It was after eleven by the time Oscar arrived and immediately he ‘drew off part of the crowd which had formed around Miss Alcott’.2

1 Jane Croly as ‘Jennie June’ in Demorest’s Monthly Magazine, June 15, 1877 , quoted in Roy Morris Jr., Declaring His Genius: Oscar Wilde in North America (Cambridge, Belknap Press, 2013), p.39

2 New York Tribune, 9 January 1882, p.5

November 24, 2016

Did Oscar Wilde Steal the Baby from the Cradle?

I’ve been immersing myself in the work of George Egerton for weeks now. She’s one of Wilde’s Women and I’ve written about her before but this weekend I’m presenting a paper at a conference on Nietzsche, Psychoanalysis and Feminism at Kingston University (it’s a big deal, Luce Irigaray is speaking & I’m quite scared). Although Egerton was often categorized as a New Woman writer, she doesn’t fit neatly with this group for various reasons. Her stories were influenced by Nietzsche’s philosophy, which she read in the original German ten years before he was translated into English. She was also interested in Wilde’s work and his commitment to individualism.

For this reason I was not at all surprised when I read of how a book replaces a baby in her intriguing story ‘The Spell of the White Elf’, which is included in her hugely popular collection Keynotes.

and then a valuable book – indeed, it is really a case of Mss., and almost unique – I had borrowed for reference, with some trouble, could not be found, and my husband roared with laughter when it turned up in the cradle.

It struck me that she must have been influenced by Wilde’s hugely significant reversal in The Importance of being Earnest, when Miss Prism admits:

In a moment of mental abstraction, for which I never can forgive myself, I deposited the manuscript in the bassinette, and placed the baby in the hand-bag.

And then I remembered that Keynotes was published in 1893, while Wilde wrote The Importance of Being Earnest during the summer of 1894, and it was first performed on 14 February 1895.

Oh Oscar!

November 21, 2016

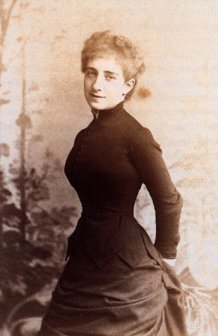

Ada Leverson: Wilde’s Wonderful Sphinx

One of the more significant women in Wilde’s Women is Oscar Wilde’s great friend and confidante Ada Leverson. I wrote a profile of her for the Bluestocking Bulletin, which I have reposted here:

BLUESTOCKING PROFILE

Ada Leverson (1862-1933)

by Eleanor Fitzsimons

Ada Leverson (née Beddington) was a friend and disciple of Oscar Wilde’s who became a widely respected satirist and novelist in her own right. Born in London, England, on 10 October 1862, she was the eldest of nine children born to Samuel Beddington, an affluent Jewish wool merchant, and his wife Zillah, who was an exceptionally talented pianist. From an early age, Ada demonstrated a passion for literature and a particular enthusiasm for the poetry of John Keats. Since her enlightened but authoritarian father arranged for her to be instructed in Latin and Greek as well as the more commonplace French and German, she was also an accomplished linguist with a deep understanding of the origins of language.

Although the Beddingtons encouraged their daughters to become educated, they were also strict disciplinarians and Ada found family life stifling. At nineteen, in a bid to find some measure of independence, she married Ernest Leverson, the son of a prosperous diamond merchant. Her father opposed the match, and with good reason; Leverson, aged thirty-one, was a compulsive gambler and philanderer who had neglected to mention that he had a daughter, Ruth, who was being raised in a convent in Paris while he courted Ada.

Ada and Ernest had little in common and theirs was not a particularly successful marriage. Yet she embraced her fate with good humour, declaring that it was: ‘better to have a ‘trying’ husband than none’. She had an exceptionally clear-eyed view of Victorian marriage and understood that, while it was imperative for a woman, marriage offered no real advantage to a man: ‘Marriage is not his profession, as it is his wife’s,’ she declared. ‘He is free in every way before marriage, tied in every way afterwards – just the reverse with her’. The Leverson’s marriage was blighted by tragedy in 1888 when their infant son George died of meningitis. A daughter, Violet, was born eighteen months later.

Although Ada was witty and exceptionally clever, she lacked confidence in her ability as a writer. For years she seemed content to contribute anonymously to publications like Black & White, The Yellow Book and Punch, while acting as a muse to more prominent, and generally male, writers. In his Memories of a Misspent Youth 1872-1896 (1933), English publisher and writer Grant Richards, who would publish the novels Ada wrote from 1907 onwards, saluted her as:

…the woman whose wit provoked wit in others, whose intelligence helped so much to leaven the dullness of her period, the woman to whom Oscar Wilde was so greatly indebted.

Ada’s friendship with Oscar Wilde was valued greatly by both. While Wilde, who nicknamed her Sphinx, praised her wit and encouraged her to write, she inspired dialogue found in some of his best loved plays: ‘Your dialogue is brilliant and delightful and dangerous,’ he declared. ‘No one admires your clever witty subtle style more than I do’. Celebrating their matched temperaments, he quipped: ‘Everyone should keep someone else’s diary; I sometimes suspect you of keeping mine’. Although she was fond of Wilde’s wife, Constance, Ada encouraged him to bring his young lovers to dinner at her home. She always enjoyed the company of witty and exuberant gay men.

Through her writing Ada helped publicise Wilde’s work. Although she detested the ‘plethora of half-witted epigrams and feeble paradoxes by the mimics of his manner’, both she and he regarded skilful parody as a form of homage: ‘One’s disciples can parody one,’ Wilde insisted, ‘nobody else’. In a letter to writer Walter Hamilton, he listed the ingredients for a worthy parody: ‘a light touch, and a fanciful treatment and, oddly enough, a love of the poet whom it caricatures’. Ada had each in abundance. She delighted in parodying her friend’s work in Punch magazine, and she displayed an uncanny talent for sending up any hint of pomposity. Her parodies can be read in the Punch archives.

In 1905, Ernest Leverson, who had lost most of his fortune, moved to Canada and invested in the lumber trade. He was joined there by his daughter Ruth, but Ada and Violet stayed in London and Ada reinvented herself as a columnist, writing the women’s column ‘White and Gold’ for The Referee magazine under the name ‘Elaine’. Apparently, she wrote propped up in bed, surrounded by a disorder of newspapers, cigarettes and oranges. Her first novel, The Twelfth Hour , was published in 1907. A trilogy,Love’s Shadow (1908), Tenterhooks (1912) and Love at Second Sight (1916), was reprinted as The Little Ottleys, in 1962, and again in 1982, when interest in her work was revived. She wrote two further novels: The Limit (1911) and Bird of Paradise (1914).

Retaining the sharp characterisation and keen ear for dialogue that she had exhibited when parodying Wilde’s work, Ada was hailed as a witty social satirist and documenter of English society who demonstrated a healthy disregard for societal conventions. She was well respected in the literary and artistic circles of 1920s London and befriended T.S. Eliot, Somerset Maugham, Ronald Firbank, and Percy Wyndham Lewis among others. When Ernest Leverson died in Canada in 1922, Ada sold her London home and divided her time between London and Florence. In 1930 Letters to the Sphinx from Oscar Wilde, with Reminiscences of the Author, which she had compiled and written shortly after Wilde’s death, was published by Gerald Duckworth and Co. Ada Leverson died in London on August 30, 1933. Her work is all but forgotten today. For more on Ada Leverson and her work read Wonderful Sphinx by Julie Speedie.

November 12, 2016

Jane Elgee & William Wilde: ‘Wed on Wednesday, Happy Match’

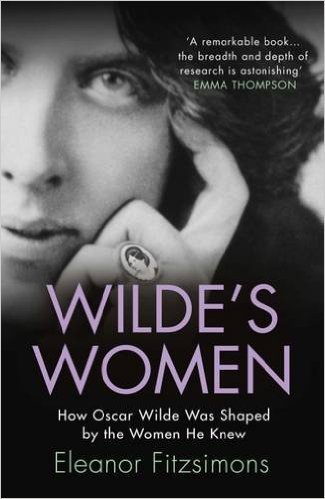

On 12 November 1851 Dr William Wilde married Jane Elgee at St. Peter’s on Aungier Street, Dublin. Here’s an excerpt from my book, Wilde’s Women to mark the occasion:

Excerpt from Chapter 3: Taming Speranza

Shortly after eight o’clock on the morning of Wednesday, 12 November 1851, , a carriage brought Dr. William Wilde and Jane’s uncle John Elgee to the door of 34 Leeson Street, the home she had shared with her mother, recently deceased, for the past eight years. To the men’s surprise, Jane was ready to leave, allowing them to reach St. Peter’s on Aungier Street [1], her parish church, in time for a nine o’clock wedding. The modest ceremony that joined ‘William R. Wilde Esq., F.R.C.S.’ and ‘Jane Francesca’ was conducted by the groom’s older brother, Reverend John M. Wilde. For the occasion, Jane had exchanged her mourning clothes for a, ‘very rich dress of Limerick lace’ with matching veil worn under a head wreath of white flowers, but she was back in black by eleven o’clock that same morning.

Both bride and groom were well known in the capital, and their dozens of acquaintances would surely have delighted in witnessing the sealing of such a dynamic alliance, but a lavish wedding would have been inappropriate on account of Sarah’s death. Describing the day to the bride’s estranged sister, Emily, Elgee hinted that the couple had married a day earlier than expected and confirmed: ‘nobody were present save our own party and the old hangers on of the church’. Perhaps they desired an auspicious start to their married life. An old folk rhyme beloved of Victorian brides advised: ‘Wed on Wednesday, happy match’. Theirs was certainly happy, but it did not lack turbulence.

After a celebratory breakfast at the Glebe house, Elgee waved the newlyweds off on their short journey to the coastal village of Kingstown, now Dun Laoghaire, where they caught the steamer to Holyhead. Judging by his letter to Emily, he was determined to improve relations between the sisters: ‘I don’t want to see open war between you and them’, he cautioned. Acknowledging that, ‘love of self’ was a prominent feature of Jane’s flamboyant character, he countered by insisting that she possessed, ‘some heart’ and, ‘good impulses’. It reassured him that she had chosen for her husband a man she clearly liked and respected: ‘Had she married a man of inferior mind he would have dwindled down into insignificance or their struggle for superiority would have been terrific’, he warned.

Notes & Sources:

[1] This was the church where her literary uncle by marriage, Charles Maturin served as Anglican Curate for the last eighteen years of his life.

Much of the detail in this post comes from a letter sent by John Elgee to Emily Warren. This letter was shown to Terence de Vere White and he quotes from it in ‘Speranza’s Secret’, Times Literary Supplement, 21 November 1980.

November 10, 2016

John Strange Winter (1856-1911) – What A Remarkable Woman!

I wrote a profile of John Strange Winter, one of the more colourful women in Wilde’s Women, for the excellent Bluestocking Bulletin recently. I’ve reproduced it below:

John Strange Winter (1856-1911)

Given the inevitable scepticism levelled at a woman who wrote fictional accounts of military matters in patriarchal Victorian Britain, it will hardly surprise you to learn that immensely successful nineteenth-century novelist “John Strange Winter” was born Henrietta Eliza Vaughan Palmer in Trinity Lane, York, on 13 January 1856. Her father, Henry Vaughan Palmer, rector of Saint Margaret’s Church in York, had served as an officer in the Royal Artillery and was a descendant of a long line of military men. This circumstance, coupled with the proximity of the Vaughan Palmer household to the York Cavalry Barracks, and the regular visits paid by the men stationed there, gave young Henrietta plenty of material for her early novels.

A disinterested scholar, she was educated at Bootham House School in York; in John Strange Winter: a volume of personal record, her biographer, Oliver Bainbridge, quoted her as saying:

“I never missed an opportunity of playing truant and attending a review. Races also were my keen delight, and I would ostensibly go to school, in reality to watch a big race from some safe and unseen coign of vantage.”

Yet, she was a voracious reader from an early age: “I always read,” she told Bainbridge.

“I think I was two and a quarter when I read aloud from a poetry book to a tax collector whom I found waiting in the hall. I suppose I thought I would beguile the tedium of his waiting.”

Henrietta, who was, in her own words, “an insatiable novel reader” from the age of four, submitted her first work of fiction to Wedding Bells magazine when she was just fourteen. She never received a reply from its editor. From the age of eighteen onwards, Henrietta, under the pseudonym Violet Whyte, wrote stories, many of them on a military theme, for the Family Herald and other popular journals. She soon attracted enthusiastic readers: Art critic John Ruskin, later godfather to two of her children, wrote a letter to the Daily Telegraph in which he referred to Henrietta as:

“the author to whom we owe the most finished and faithful rendering ever yet given of the British soldier.”

Yet, in 1881, publisher Chatto and Windus refused to bring out Cavalry Life, a collection of her “regimental sketches,” under a woman’s name, arguing that no reader would believe it was not written by a man. To circumvent this, Henrietta borrowed the name “John Strange Winter” from one of her characters in Cavalry Life.

Readers and reviewers were duped. One reviewer for the Morning Post insisted:

“His [sic] intimate knowledge of the inner life of barracks, and his tales of soldiers and their ways are accurate, whilst they are without exception bright and amusing.”

So convincing was this assumed identity that the committee of the Royal Literary Fund wrote to her publishers inviting eminent literary gentleman Mr. John Strange Winter to act as a steward at their anniversary dinner. Henrietta was obliged to write and point out that, as she was a woman, this was not allowable under their rules. To their credit, once the Royal Literary Fund voted to allow women members, she was the first they approached.

In time, Henrietta was outed as a woman, most notably when an announcement appeared in the press congratulating John Strange Winter on the birth of twins. She had four children, three girls and a boy, with her husband Arthur Stannard, who she married in 1884 after a very short courtship. Once her identity was revealed, Henrietta was free to appear in public. She made her debut as a public reader in the Putney Assembly Rooms in 1886, at a charity event she had organised on behalf of a local man who had fallen on hard times. This was characteristically generous of her. The proceeds of her novel A Soldier’s Children were donated to the Victoria Hospital for Children in Chelsea.

Henrietta enjoyed huge success with Bootles’ Baby: A story of the Scarlet Lancers, which was serialised in the Graphic in 1885 and sold two million copies in book form. A dramatised version, first staged in 1889, toured for four years. In 1891, she also launched Golden Gates, a penny weekly illustrated magazine that she ran almost single-handedly. She changed its name to Winter’s Weekly after twelve months and it survived until 1895. Henrietta did much to help fellow women writers too. Well regarded in journalistic circles, she played a pivotal role in convincing the Society of Authors to facilitate the election of women to official positions. She also helped establish the Writers’ Club, a rival women-only body; in 1892, she was appointed its first president. That same year, she established the Anti-Crinoline League, a crusade against “ridiculous, vulgar, inelegant, and ungraceful” skirts that often caught fire, resulting in the death of the wearer.

In 1896, as Arthur’s health was deteriorating, the Stannard family moved to Dieppe on the advice of his doctors. An enthusiastic ex-pat, Henrietta is credited with turning the town into a popular tourist resort by means of her glowing accounts of its many charms. She returned to London in 1901, but retained a holiday home in Dieppe until 1909. (Michael Seeney’s article ‘John Strange Winter and Dieppe’, published in The Wildean No. 23, July 2003, gives an excellent account of her time there.)

On her return, Henrietta was elected president of the Society of Women Journalists. As sole supporter of her family, she was obliged to earn a second income from the sale of cosmetic preparations of her own devising after a paper she had started failed, leaving her in debt. By then, her own health was poor; she had been diagnosed with breast cancer and undergone a mastectomy. Henrietta Vaughan Stannard died in 1911 following complications arising from an accident. She was fifty-five. Her last novel as John Strange Winter, Miss Peggy: the Story of a Very Modern Girl, was published posthumously the year after her death, adding to more than one hundred novels and story collections from her pen. Many can be read online here.

November 1, 2016

Oscar Wilde & George Bernard Shaw: An Uneasy Admiration

I was delighted with the very warm welcome I received when I addressed the Shaw Society on links between Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw in London last week. Shaw features in my book Wilde’s Women but I added much more detail for the occasion. I have reproduced my script here (warning, it’s a long one!)

OSCAR WILDE AND GEORGE BERNARD SHAW FOR THE SHAW SOCIETY

27 OCTOBER 2016

CONWAY HALL

Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw had much in common. Both Dubliners, born within twenty minutes walk of each other. Both of a similar age: Wilde was less than two years older than Shaw. Both inventive men who remained dogged in their questioning of the status quo. Together, they were recognised as the first Irish playwrights in decades to make an impact on the London stage

Yet, they were wildly different in both temperament and inclination, and, as a result, they developed no more than an uneasy and rather distant relationship. They never became close friends and met on only a handful of occasions, mostly by chance rather than arrangement. Despite this coolness, each held the other’s talent in high regard and both were influenced by ideas conceived by the other.

A little background information to start: George Bernard Shaw was born at 3 Upper Synge Street, in the lower-middle class Portobello district of Dublin city, on 26 July 1856. His father, George Carr Shaw, was an ineffectual, alcoholic civil-servant-turned-corn-merchant. His mother, Bessie, who was considerably younger than her husband, was a rather disillusioned and distant presence. An exceptionally accomplished singer, she introduced music into her son’s life.

3 Upper Synge Street

At the time of Shaw’s birth, Wilde, aged 22 months, was living twenty minutes walk away at 1 Merrion Square, an opulent residence described by his mother, Jane, who, as Speranza, was a significant literary figure in her native city, as having ‘fine rooms and the best situation in Dublin’. Wilde’s father, Dr. William Wilde was an eminent eye and ear surgeon, and an accomplished author with a keen interest in history and folklore. He was also reckless with money and a notorious philanderer who was involved in a sex scandal, the Travers affair, which broke his spirit.

1 Merrion Square North

Although there is no record of them ever meeting in Dublin, Shaw was certainly aware of the brilliant, flamboyant Wilde family. In ‘My Memories of Oscar Wilde’, the biographical portrait he contributed to Frank Harris’s Oscar Wilde, His Life and Confessions’ (1916), he describes his first encounter with William and Jane Wilde:

I was a boy at a concert in the Antient Concert Rooms in Brunswick Street in Dublin. Everybody was in evening dress; and – unless I am mixing up this concert with another (in which case I doubt if the Wildes would have been present) – the Lord Lieutenant was there with his blue waistcoated courtiers. Wilde was dressed in snuffy brown; and he had the sort of skin that never looks clean, he produced a dramatic effect beside Lady Wilde (in full fig) of being, like Frederick the Great, Beyond Soap and Water, as his Nietzschean son was beyond Good and Evil. He was currently reported to have a family in every farmhouse; and the wonder was that Lady Wilde didn’t mind – evidently a tradition from the Travers case, which did not know about until I read your account, as I was only eight in 1864.

Shaw also recalled:

Sir William Wilde…operated on my father to correct a squint, and overdid the corrections so much that my father squinted the other way all the rest of his life.

The explanation for Shaw’s early presence in the Antient Concert Rooms may be that this was the venue used by his mother’s music teacher George John Vandeleur Lee to stage his Amateur Musical Society concerts. In fact, one of Lee’s best-known singers was Bessie Shaw. Incidentally, years later, Shaw appeared on that stage too, as a speaker rather than a singer.

In 1873, when Shaw was almost sixteen, Bessie moved to London with Lee, taking her daughters with her. Lucinda, always called Lucy, the oldest child, became a successful music hall singer. Elinor, the middle child, died of TB in a sanatorium on the Isle of Wight on 27 March 1876. Shaw remained with his father in Dublin, to complete his education and afterwards, worked as an office boy for a land agent, a job he hated. He considered his expertise in literature, theatre and music as hard won when compared to the privileged start enjoyed by Wilde, who had the finest education and moved within rarefied circles from childhood.

In April 1876, Shaw joined his mother and surviving sister in London. In November of that year he was invited to Lady Wilde’s home at Park Street – she had moved to London after the death of her husband. Shaw speculated that Lady Wilde took an interest in him as the brother of Lucy Shaw, who may have been popular with the Wilde boys. He wrote: ‘The explanation must be that my sister, then a very attractive girl who sang beautifully, had met and made some sort of innocent conquest of both Oscar and Willie.’ At that time, Wilde was an undergraduate at Magdalen College, Oxford, taking a degree in literæ Humaniores, or Greats.

Lucy Shaw

Shaw was grateful for Lady Wilde’s kindness and patronage at a difficult time in his life – he was working part-time at the Edison phone company and spending his free time in the reading room of the British Museum attempting to write novels. ‘Lady Wilde was nice to me in London,’ he remembered:

during the desperate days between my arrival in 1876 and my earning of an income by my pen in 1885, or until a few years earlier when I threw myself into socialism and cut myself contemptuously loose from everything of which her “At Homes“ themselves desperate affairs enough ‘were part.

Shaw met Wilde at one of Lady Wilde’s gatherings, an encounter he recalled with mixed emotions. Wilde, he wrote:

…came and spoke to me with an evident intention of being specially kind to me. We put each other out frightfully; and this odd difficulty persisted between us to the very last, even when we were no longer mere boyish novices and had become men of the world with plenty of skill in social intercourse. I saw him very seldom [Shaw recalled possibly between six and twelve’s times from first to last], as I avoided literary and artistic coteries like the plague….

As Shaw developed an interest in socialism, he began to avoid invitations to Lady Wilde’s gatherings, but he met Wilde elsewhere. The first mention of Wilde recorded in his diary is in September 1886, when both were guests at the home of Irish novelist and historian Joseph Fitzgerald Molloy. Wilde, who was also interested in socialism, but had his own distinctive take which differed greatly from Shaw’s and was rooted in individualism, reportedly listened somewhat sympathetically to Shaw’s plans for the establishment of a socialist magazine, although it is also reported that he teased him about its name.

However grudgingly, Shaw admired Wilde. Praising ‘Oscar’s wonderful gift as a raconteur’, he recalled an enjoyable day they spent in each other’s company. What also drew Shaw to Wilde was gratitude when he alone signed Shaw’s petition of 1887 requesting that those involved in the Haymarket riots in Chicago in May 1886 be reprieved. Afterwards, he wrote:

It was a completely disinterested act on his part; and it secured my distinguished consideration for him for the rest of his life.

In November 1887, Shaw wrote in his diary that he ‘had a talk with Wilde’ at Lucy Shaw’s wedding tea at St. John’s Church.

The careers of both Irishmen followed a similar trajectory. As both wrote anonymous reviews for the Pall Mall Gazette, it seems Wilde’s submissions, three to four per month, were occasionally misattributed to Shaw, and vice-versa (Shaw confirmed this to biographer and editor David J O’Donoghue). Shaw would surely not have minded, since he admired Wilde’s style, describing it as ‘exceptionally finished in style and very amusing’.

As a book reviewer, Shaw reviewed Lady Jane Wilde’s Ancient Legends of Ireland in July 1888, and concluded that ‘probably no living writer could produce a better book of its kind’ – faint praise that may have reflected gratitude for her kindness despite his lack of interest in her subject. He also insisted that her ‘position, literary, social and patriotic’ was ‘unique and unassailable’.

On 6 July 1888, Wilde attended a meeting of the Fabian Society in Willis’s Rooms. There, he listened to artist Walter Crane, who had illustrated his The Happy Prince and Other Tales, published just a few weeks before. Crane spoke on “The Prospects of Art under Socialism.” Wilde’s attendance was reported in evening newspaper the Star, as was Shaw’s:

Mr. Oscar Wilde, whose fashionable coat differed widely from the picturesque bottle-green garb in which he appeared in earlier days, thought that the art of the future would clothe itself not in works of form and colour but in literature…. Mr. Shaw agreed with Mr. Wilde that literature was the form which art would take….

Although Shaw, writing to Frank Harris, claimed it was a talk he had delivered that influenced ‘The Soul of man Under Socialism’, several of his biographers, among them Stanley Weintraub and Karl Beckson, believe it was this lecture by Crane combined with a discussion Wilde had with Shaw afterwards.

Of course Shaw and Wilde are recognised primarily as playwrights nowadays. Recognising a connection between their works, in 1893, Wilde initiated a pattern by sending Shaw a copy of Lady Windermere’s Fan, with the inscription “Op 1 of the Hibernian School, London ’93”. He also sent a copy of the French version of Salomé in February 1893, but excluded this from the Hibernian School, reciprocation for Shaw’s gift of his The Quintessence of Ibsenism, about which Wilde wrote:

…your little book on Ibsenism and Ibsen is such a delight to me that I constantly take it up, and always find it stimulating and refreshing: England is the land of intellectual fogs but you have done much to clear the air: we are both Celtic, and I like to think that we are friends….

In this letter Wilde also praised Shaw’s opposition to theatre censorship. As Salomé had just been refused a licence, this was a very welcome stance on the part of his countryman.

When Salomé went astray, Shaw was prompted to write:

Salome is still wandering in her purple raiment in search of me and I expect her to arrive a perfect outcast, branded with inky stamps, bruised by flinging into red prison [PO] vans, stuffed and contaminated by herding with review books…I hope to send you soon my play Widowers’ Houses which you will find tolerably amusing.

He did indeed reciprocate with Op 2, his first play, Widowers’ Houses, in May 1983. Wilde responded with a letter:

I have read it twice with the keenest interest. I like your superb confidence in the dramatic value of the mere facts of life. I admire the horrible flesh and blood of your creatures, and your preface is a masterpiece – a real masterpiece of trenchant writing and caustic wit and dramatic instinct.

Wilde’s A Woman of No Importance became Op 3, while Arms and the Man became Op 4 – Wilde attended the first night in April 1894. They got as far as Op 5, An Ideal Husband, which Shaw reviewed for Frank Harris’s Saturday Review, disagreeing with the assertion of sneering critics that Wildean ‘epigrams can be turned out by the score by any one light-minded enough to condescend to such frivolity’. ‘As far as I can ascertain,’ he went on, ‘I am the only person in London who cannot sit down and write an Oscar Wilde play at will’.

He concluded:

In a certain sense Mr Wilde is our only thorough playwright. He plays with everything: with wit, with philosophy, with drama, with actors and audience, with the whole theatre.

Undoubtedly, Shaw had a high opinion of Wilde’s talent. In an interview with The Star, published on 29 November 1992, he described Wilde as ‘unquestionably the ablest of our [Irishmen’s] dramatists’. When Lady Colin Campbell, who succeeded Shaw as art critic of the World, expressed dislike for A Woman of No Importance, Shaw insisted that Wilde’s epigrams were far superior to the “platitudes” of other dramatists and informed her:

There are only two literary schools in England today: the Norwegian school and the Irish school. Our school is the Irish school; and Wilde is doing us good service in teaching the theatrical public that “a play” may be a playing with ideas instead of a feast of sham emotions…. No, let us be just to the great white caterpillar: he is no blockhead and he finishes his work, which puts him high above his rivals here in London…. (May 1893)

The remark commonly attributed to Wilde that Shaw ‘has no enemies, but is intensely disliked by all his friends’ originates with W.B. Yeats who regarded Shaw as a ‘cold-blooded Socialist’. It is a version of a quote from Dorian Gray. Yet Shaw seemed to accept it as genuine, and told Ellen Terry in 25 September 1896: ‘Oscar Wilde said of me “An excellent man: he has no enemies; and none of his friends like him”‘.

The Importance of Being Earnest

Shortly before the ill-fated action for libel Wilde took against the Marquess of Queensberry began, Shaw encountered him while lunching with Frank Harris at the Cafe Royal. Wilde expressed unhappiness with Shaw’s poor review of The Importance of Being Earnest, and fell out with Harris when he attempted to persuade him to drop the libel case. In 1950, months before his death, Shaw revisited Earnest in a letter to playwright St. John Ervine, describing it as ‘a mechanical cat’s cradle farce without a single touch of human nature in it’. Claiming that he was present at ‘all the Wilde first nights’, he summed up by writing:

It amused me by its stage tricks (I borrowed the best of them) but left me unmoved and even a bit bored and quite a lot disappointed.

Weintraub saw traces of Earnest in Shaw’s You Never Can Tell, which had ‘something of Wilde in it’, specifically he believed, ‘the wordplay on earnestness is too pervasive to be coincidence’. In Man and Superman (1903), Shaw writes: “There are two tragedies in life. One is to lose your heart’s desire. The other is to gain it.” In Lady Windermere’s Fan, Wilde had written: “In this world there are only two tragedies. One is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.” In Major Barbara (1905), Shaw’s imperious Lady Britomart bares a close resemblance to Wilde’s Lady Bracknell.

After Wilde was imprisoned, Shaw drafted a petition to the Home Secretary asking that he be released. He discussed its circulation with Wilde’s brother Willie, but the brothers were estranged and Willie, showing little enthusiasm, quipped, according to Shaw: ‘Oscar was NOT a man of bad character: you could have trusted him with a woman anywhere’. Disheartened, Shaw concluded that, since only he and the Reverend Stuart Headlam had signed, it would be of little use ‘as we were two notorious cranks and our names alone would make the thing ridiculous and do Oscar more harm than good’.

Instead, contrary to press policy, Shaw went out of his way to praise Wilde’s work and keep his name in the public eye. Reviewing a minor play by Charles Hawtrey in which Charles Brookfield had a minor role, both men had conspired against Wilde, in the Saturday Review in October 1896, Shaw compared it to ‘the comedies of Mr. Wilde, and insisted: ‘Mr. Wilde has creative imagination, philosophic humour, and original wit, besides being a master of language, whilst Mr. Hawtrey observes, mimics and derides quite thoughtlessly’. In 1897, when it was suggested in literary periodical the Academy that an Academy of Letters be founded, Shaw wrote a letter to the editor suggesting that only Henry James and Oscar Wilde deserved to be nominated. The academy never materialised. Later, Shaw defended Wilde in a lengthy open letter to New York anarchist publication Liberty.

When Wilde was living in Paris after his release from prison, Shaw made a point of sending him his work as it was published and Wilde reciprocated. Shaw’s last contact with Wilde was when the latter sent him an inscribed copy of the Ballad of Reading Gaol from Paris in 1898. In 1905, five years after Wilde’s death, when his prison letter appeared as De Profundis, Robert Ross sent a copy to Shaw. Although Shaw wrote in his biography of Harris: ‘We all dreaded to read de Profundis’, he had a high opinion of it and wrote to thank Ross:

It is really an extraordinary book, quite exhilarating and amusing as to Wilde himself, and quite disgraceful & shameful to his stupid tormentors. There is pain in it, inconvenience, annoyance, but no unhappiness, no real tragedy, all comedy. The unquenchable spirit of the man is magnificent: he maintains his position & puts society squalidly in the wrong – rubs into them every insult & humiliation he endured – comes out the same man he went in – with stupendous success.

Throughout his life, Shaw was asked to comment on Wilde but he generally refused. In his 1918 preface to Frank Harris’s Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions titled “My Memories of Oscar Wilde” (actually, a letter, to which Harris added the title and edited the contents, Shaw, rather bizarrely attributed Wilde’s fate to his size, writing: ‘I have always maintained that Oscar was a giant in the pathological sense and that this explains a good deal of his weaknesses’. An odd comment since, although Wilde was well above average height at 6’ 3”, Shaw was almost 6’ 2”.

Shaw with Nancy Astor, Charlie Chaplin & Amy Johnson

During the 1930s, Shaw collaborated with Lord Alfred Douglas on a biography of Frank Harris, and the two corresponded. Shaw told Douglas:

I think Wilde took you both [Harris and Douglas] in by the game he began to amuse himself [with] in prison: the romance of the ill treated hero and the cruel false friend.

He also wrote:

The Queensberry affair was your tragedy and, comparatively, Wilde’s comedy’. In a sense this inverts a line from de Profundis: ‘I thought life was going to be a brilliant comedy, and that you were to be one of many graceful figures in it. I found it to be a revolting and repellent tragedy…

In 1940, in a response to an anonymous review of Lord Alfred Douglas’s Oscar Wilde: a Summing Up in the TLS, Shaw wrote to the editor of the Times Literary Supplement discussing the legalities of the case, since this reviewer had stated that Douglas was misled by Shaw in his assessment of Wilde’s conviction. In an interesting commentary regarding the distinction between ‘vice and crime’, Shaw wrote the following:

Oscar Wilde, being a convinced pederast, was entirely correct to his plea of Not Guilty; but he was lying when he denied the facts; and the jury, regarding pederasty as abominable, quite correctly found him Guilty.

He gives no indication as to his own view, merely confines himself to commentary on the law.

According to H. Montgomery Hyde, when reviewing Wilde’s short life, Shaw, who clearly felt some fellowship with Wilde based on their shared nationality declared:

It must not be forgotten that though by culture Wilde was a citizen of all civilized capitals, he was at root a very Irish Irishman, and, as such, a foreigner everywhere but in Ireland.

Previously, he had defended Wilde’s controversial congratulating of the audience after Lady Windermere’s Fan as ‘an Irishman’s way of giving all the credit to the actors and effacing his own claims as author’. He also condemned the critics’ dismissal of An Ideal Husband by claiming that an Englishman ‘can no more play with wit and philosophy than he can with a football or a cricket bat’. He attributed Wilde’s refusal to run from his trials to his ‘fierce Irish pride’.

Oscar Wilde died in Paris on 30 November 1900. Writing to Harris sixteen years later, Shaw concluded:

I am sure Oscar has not found the gates of heaven shut against him; he is too good company to be excluded; but he can hardly have been greeted as, “Thou good and faithful servant’.

An affectionate summation of a man he admired but never loved.

October 21, 2016

Pantisocracy: Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey & the search for utopia

Today (21 October) marks the anniversary of the birth of poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was born in Devon, England in 1772. A leader of the British Romantic movement, his best known poems are: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Christabel, and Kubla Khan. His idealism is best exemplified perhaps by his ultimately unsuccessful attempt to establish a utopian community with friend and fellow poet Robert Southey.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

By 1793, Southey aged nineteen and a student at Oxford University, had grown disillusioned with the lack of reform that characterised the aftermath of the French Revolution, and by the persistence of inequality in his native England. As a result, his thoughts turned to a simpler life in America, a new world untainted by the evils of established society.

Robert Southey

In 1794, Southey was introduced to Coleridge, a student at Cambridge University. They founded a firm friendship on their common commitment to social justice and civil liberty, and formulated a plan to move to America, where they would establish Pantisocracy. This new word was derived from ‘Pan-socratia’, the Greek word for governance by all. They considered ‘Aspheterism’, the holding of property in common ownership, as a key principle. Southey envisaged Pantisocracy as a society:

…where the common ground was cultivated by common toil, and its produce laid in common granaries, where none are rich because none should be poor, where every motive for vice should be annihilated and every motive for virtue strengthened.

Underpinning their scheme was a melange of ideas garnered from the writings of Plato, Paine, Priestley, Hartley, Godwin, and Dyer. This new utopia would, they believed, arise from a commitment to benevolence and civil liberty, a concern for human rights, and an awareness of the perfectibility of mankind. As Southey saw it:

Their wants would be simple and natural; their toil need not be such as the slaves of luxury endure; where possessions were held in common, each would work for all; in their cottages the best books would have a place; literature and science, bathed anew in the invigorating stream of life and nature, could not but rise reanimated and purified.

Women had a place in this idyll too, albeit a subordinate one. As Southey explained:

Each young man should take to himself a mild and lovely woman for his wife; it would be her part to prepare their innocent food, and tend their hardy and beautiful race.

Southey had a clear vision for how he and his fellow-idealist would spend their days, writing:

When Coleridge and I are sawing down a tree, we shall discuss metaphysics; criticize poetry when hunting a buffalo; and write sonnets whilst following the plough. Our society will be of the most polished order.

Originally, they thought of settling in Kentucky, but they shifted their sights to the Susquehanna Valley in Pennsylvania. The plan was to invite ten like-minded men and their families to join them. Initially, wealthier members would support the less well off until they became self-sufficient. They were certain that this would be the first of many such communes.

Susquehanna Valley, Pennsylvania

Although the pair planned to travel to the new world in 1795, they were woefully underprepared. As a result of having studied the misleading promotional accounts that were reaching England from America, they underestimated the physical labour required to set up a new community. For some reason, they assumed that only four hours a day need be dedicated to work, the rest being available for contemplation.

Funding was also an issue. The original plan was that Southey’s wealthy aunt, Elizabeth Tyler, would put up capital. However, when she learned of his plans, and worse still his intention to marry seamstress Edith Fricker, she disinherited him and ejected him from her house into a violent rainstorm. As a result, Southey scaled back the plan. He began to talk of settling on a farm in Wales, of hiring servants to do the bulk of the manual labour, and of retaining private ownership of land with the exception of a small plot to be held communally.

Coleridge was incensed and condemned Southey as a traitor. Since he too had believed he would need a wife to accompany him to America, he had married Edith’s sister Sarah, but theirs was an unhappy union. He never returned to Cambridge but began his career as a writer instead. Having spent some time collaborating with William Wordsworth, he dedicated the next two decades to composing poetry, lecturing on literature and philosophy, and publishing tracts on religious and political theory. Although he lived off grants and donations for the most part, he did spend two years on the Island of Malta working as Acting Public Secretary of Malta under the Civil Commissioner, Alexander Ball, a post he had accepted in an effort to overcome poor health and a calamitous addiction to opium.

Unable to break his dependence on opium,Coleridge moved to London in 1816, to live in the home of his physician, James Gillman. Although his behaviour was erratic, and he developed a conviction that the world was about to end, he continued to produce wonderful work, including Biographia Literaria, a volume of his finest literary criticism; Sibylline Leaves; Aids to Reflection; and Church and State.

Coleridge died in London on July 25, 1834. The cause of death was recorded as heart failure compounded by a lung disorder that may have resulted from his opium addiction. He was sixty-one and had lived separately from his family for two decades by then.

You can find the modern day Pantisocracy, an excellent cabaret of conversation presided over by Dr Panti Bliss at this link here.

Coleridge has absolutely nothing to do with Oscar Wilde or Wilde’s Women, but you might like to read it anyway.

October 19, 2016

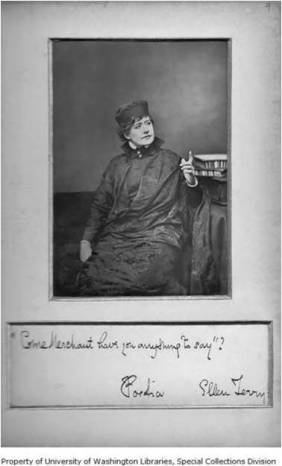

Oscar Wilde & Ellen Terry

This is the script of a talk I gave to the Oscar Wilde Society on a visit to Smallhythe Place, once home to Ellen Terry, in September 2016. Do join the society. Such warm and wonderful people keeping the memory of Wilde alive!

Although he would surely have been aware of an actress with a reputation as stellar as Ellen Terry’s, it’s believed that the first time Oscar Wilde saw her perform was when he went with David Hunter Blair, a friend from Oxford University, to see her in Tom Taylor’s comedy New Men and Old Acres at the Court Theatre, London in December 1878. Fellow Irish playwright, George Bernard Shaw, fell in love with Terry on the strength of her performance in that play.

Six months later, on 27 June 1879, Wilde watched Terry play Queen Henrietta Maria in Charles I by W. G. Wills at the Lyceum Theatre. He was 24 years old and had just come down from Oxford University with a double first. She was 8 years older at 32, had been married to and separated from artist G. F. Watts, and had two children with Edward Godwin, from whom she had recently split. In 1878, she had left the Court Theatre to become leading lady with Henry Irving’s company at the Lyceum Theatre.

Wilde was mesmerised by Terry’s performance and wrote a sonnet in her honour, as was his habit. He sent it to her along with a letter expressing his ‘loyal admiration’ for her talent. He declared:

‘No actress has ever affected me as you have. I do not think you will ever have a more sincere an impassioned admirer than I am’.

Three weeks later, his sonnet, now titled ‘Queen Henrietta Maria’ was published in society periodical The World. It began:

In the lone tent, waiting for victory,

She stands with eyes marred by the mists of pain,

Like some wan lily overdrenched with rain;

Terry was very taken with Wilde’s poetic tribute. In her autobiography The Story of my Life, she wrote:

‘That phrase ‘wan lily’ represented perfectly what I had tried to convey, not only in this part, but in Ophelia. I hope I thanked Oscar enough at the time. Now he is dead and I cannot thank him any more…I had so much bad poetry written to me that these lovely sonnets from a real poet should have given me the greater pleasure.’

When Terry appeared in The Merchant of Venice in 1879, Wilde wrote a new sonnet, ‘Portia’, as a tribute to her beauty:

‘For in that gorgeous dress of beaten gold,

Which is more golden than the golden sun,

No woman Veronese looked upon

Was half so fair as thou whom I behold.’

This ‘gorgeous dress of beaten gold’ is on display in Smallhythe Place.

Terry’s performance as Camma, Tennyson’s Priestess of Artemis in The Cup in January 1881, prompted Wilde to compose a third sonnet, ‘Camma’, in which he expressed a desire to see her play Shakespeare’s Cleopatra. She never did.

Wilde included all three of the sonnets he had written for Terry in his collection Poems, published by David Bogue in 1881 at Wilde’s own expense. Although it garnered a mixed critical response and many of the poems were considered derivative, it is worthy of perusal.

So was it simply Wilde’s admiration for Terry’s beauty and talent that prompted these tributes? Since he was a very ambitious young man, it seems certain that they were intended to foster a close association with one of the most famous women in London. Certainly, he would have loved to have persuaded Terry interpret his work.

In 1880, Wilde sent Terry a copy of his first play, Vera, beautifully bound in dark red leather with her name embossed in gold on the binding and inscribed ‘from her sincere admirer the author’. The letter that accompanied it contained the line:

‘Perhaps someday I shall be fortunate enough to write something worthy of your playing’.

Terry was flattered but turned Vera down.

Wilde and Terry moved in the same bohemian circles and had become friends by then. She was a regular visitor to 13 Salisbury Street, the home he shared with artist Frank Miles. Early in 1880, Terry persuaded Wilde to share her box at the Criterion Theatre to watch an adaptation of James Albery’s Where’s The Cat, a satire on Aestheticism, in which Wilde was apparently parodied by Herbert Beerbohm Tree. Little wonder he declared the play to be ‘poor’.

One incident that illustrates how close Wilde and Terry had become occurred when Terry was about to take to the stage in the Lyceum to play Camma in The Cup. Another member of the cast that night was Florence Balcombe, Wilde’s former girlfriend and now Mrs. Bram Stoker. Stoker husband was the business manager of the Lyceum and Irving’s right-hand man. The very beautiful Florence, who did not pursue an acting career, had a tiny part as a vestal virgin.

It seems that Wilde still harboured feelings for lovely Florence, since he sent two crowns of flowers to Terry, accompanied by this revealing note:

Will you accept one of them, whichever you think will suit you best. The other – don’t think me treacherous, Nellie – but the other please give to Florrie from yourself. I should like to think that she was wearing something of mine the first night she comes on the stage, that anything of mine should touch her. Of course if you think – but you won’t think she will suspect? How could she? She thinks I never loved her, thinks I forget. My God how could I!

The admiration between Wilde and Terry was mutual. He christened her ‘Our Lady of the Lyceum’ and called her ‘the kindest-hearted, sweetest, loveliest of women’. He also sent her a photograph inscribed ‘for dear wonderful Ellen’.

She declared of him:

‘The most remarkable men I have known were, without a doubt, Whistler and Oscar Wilde…there was something about both of them more instantaneously individual and audacious than it is possible to describe’.

When Terry embarked on her first tour of America with the Lyceum company in October 1883, she recalled seeing Wilde, accompanied by Lillie Langtry, standing on the quayside in Liverpool, waiting to see them off. She noticed that he held his hand to his mouth to hide his ‘ugly teeth’ but she remarked on his ‘beautiful eyes’. Wilde had toured America the previous year and Langtry had arrived for her first tour towards the end of his.

Terry’s encouragement of Langtry’s ambitions to become an actress, a path she had embarked on at Wilde’s suggestion, and her open admiration for her potential rival’s beauty, endeared her further to Wilde. When Langtry played Rosalind in As You Like It in 1882, Terry sent her a letter of encouragement, followed by a telegram.

Dear Nellie,

I bundled through my part somehow last night, a disgraceful performance, and no waist-padding! Oh what an impudent wretch you must think me to attempt such a part! I pinched my arm once or twice last night to see if it were really me. It was so sweet of you to write me such a nice letter, and then a telegram, too!

Yours ever, dear Nell

Lillie

This was a particularly unselfish act since Terry never got to play this coveted part.

Lillie Langtry as Rosalind

When Wilde was courting Constance Lloyd in 1883, he took her to see Othello at the Lyceum, with Terry as Desdemona. Afterwards, Constance became a regular at the theatre and frequently dined with Terry and Irving after shows. Another connection was established when Edward Godwin, Terry’s former partner and the father of her children, decorated the Wilde’s home in Tite Street in 1884.

Wilde loved Terry’s interpretations of Shakespeare’s women. His review of the Lyceum’s Hamlet for the Dramatic Review on 9 May 1885, was full of praise for her:

And of all the parts which Miss Terry has acted in her brilliant career, there is none in which her infinite powers of pathos and her imaginative and creative facility are more shown than in her Ophelia. Miss Terry is one of those rare artists who needs for her dramatic effect no elaborate dialogue, and for whom the simplest words are sufficient.

His review of The Lyceum’s production of an adaptation of Olivia by W.G. Wills, written for the Dramatic Review on 30 May 1885, included the observation that:

To whatever character Miss Terry plays she brings the infinite charm of her beauty and the marvellous grace of her movements and gestures. It is impossible to escape from the sweet tyranny of her personality. She dominates the audience by the secret of Cleopatra.

In that same review, having praised her interpretation of Olivia, he observed:

There was, I think, no one in the theatre who did not recognise that in Miss Terry our stage possesses a really great artist, who can thrill an audience without harrowing it, and by means that seem simple and easy can produce the finest dramatic effects.

In May 1888, Wilde sent a copy of The Happy Prince and Other Tales to Terry. In response, she wrote:

They are quite beautiful, dear Oscar, and I thank you for them from the best bit of my heart…I should like to read one of them someday to NICE people – or even NOT nice people, and MAKE ‘em nice.

Unfortunately, his plans for her to undertake a series of public readings never came to fruition.

In 1889, when Terry’s carriage passed the window of Wilde’s Tite Street home and he noticed that she was wearing her costume for Lady Macbeth, an emerald gown shimmering with the iridescent wings of a thousand jewel beetles, he remarked:

‘The street that on a wet and dreary morning has vouchsafed the vision of Lady Macbeth in full regalia magnificently seated in a four-wheeler can never again be as other streets: it must always be full of wonderful possibilities.’

He included an image of the finished painting as the frontispiece to the July 1889 issue of The Woman’s World, which he edited at the time.

Terry too loved the dress and wrote:

‘One of Mrs. Nettle’s greatest triumphs was my Lady Macbeth dress, which she carried out from Mrs Comyns Carr. I am glad to think it is immortalised in Sargent’s picture. From the first I knew that picture was going to be splendid.’

In 1892, Ellen’s sister Marion Terry played Mrs. Erlynne in the very first production of Lady Windermere’s Fan. Although the part was intended for Lillie Langtry, it was to be her most significant role.

The truest test of Terry’s friendship for Wilde came in the wake of his arrest for gross indecency in 1895. While many of his friends abandoned him, one closely-veiled woman called to his mother’s house, where he was staying, bringing a bouquet of violets, the symbol of faithfulness, and a horseshoe for luck. She was identified by Henry Irving’s son Lawrence as Ellen Terry. She also wrote to Constance at that time offering her help and support.

In 1900, when Wilde was living in Paris, Terry visited the city with Amy Lowther. They spotted their friend, much diminished, gazing longingly through the window of a patisserie and biting his fingers with hunger. When they invited him to eat with them, they were much relieved when he ‘sparkled just as of old’. Neither ever saw him again.

After learning of Wilde’s death, Terry stopped his friend Robert Sherard

‘to talk of Wilde and to say many beautiful and kind things about him.’

When she spoke at a dinner held in her honour by the Gallery First-Nighters’ Club in 1905, she included ‘the late Oscar Wilde’ in a list of people seen regularly ‘in the gallery and pit at the dear old Lyceum’.This was a brave statement at the time.

Yet, when writer and poet Richard Le Gallienne asked her to write a foreword to a memorial edition of The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, it seems she never responded.

One final echo of Wilde and his relationship with Terry appeared twelve years after his death in ‘The Mask’ magazine in July 1912. A story called ‘The Actress’, which Wilde told to Aimee Lowther when she was a child but never wrote down, was published by the magazine’s editor, Edward Craig, Terry’s son. This lovely story of an actress who leaves the stage to devote herself to a lover but is forced to choose between them when love is waning is thought to have been inspired by Terry. Naturally, she chooses the stage.

For more on Oscar, Ellen & all the other women in his life (with full references) read Wilde’s Women.

October 12, 2016

‘The subtle imagination and passionate artistic nature of Mme Modjeska’

Helena Modjeska by Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz, 1880

In 1880, when Polish actress, and one of Wilde’s Women, Helena Modjeska arrived in London to star in Heartsease, the English title chosen for Dumas’ La Dame aux Camelia, at the Court Theatre, she asked of Oscar Wilde:

‘What has he done, this young man that one meets him everywhere? Oh yes he talks well, but what has he done? He has written nothing, he does not sing or paint or act – he does nothing but talk. I do not understand.’ 1

Born to Józefa Benda, the widow of a wealthy merchant in Kraków in 1840, Modjeska was a veteran of the stage of the stage by the time she arrived in London. At twenty, she had joined a company of strolling players managed by Gustav Modrzejewski, who she married and had two children by before discovering that he already had a wife who was very much alive.

Modjeska left Modrzejewski after their daughter, Marylka, died in infancy in 1865. She took their son Rudolf, later renamed Ralph Modjeska, to Krakow with her. There, she accepted a four-year theatrical engagement before moving to Warsaw in 1868, where she forged a reputation as a talented theatrical actress. Her two brothers, Józef and Feliks Benda, were also well regarded actors.

On 12 September 1868, Modjeska married Polish nobleman Karol Bozenta Chlapowski, who was editor of the liberal nationalist newspaper Kraj. Their home became the focus of Krakow’s dissident, artistic and literary milieu. The couple’s political activities attracted the attention of authorities and in 1876,they felt obliged to flee to California, where Chlapowski established an experimental and idealistic colony of Polish expatriates on a remote ranch in California. A good account of daily life on the ranch is included in Theodore Payne’s memoir, Life on the Modjeska Ranch in the Gay Nineties.

When this experiment failed spectacularly, leaving them penniless, Modjeska was obliged to resume her career. Although she had been principal actress at the Polish National Theatre, she needed to learn English to secure major roles. She accomplished this in a matter of months by practising the language between performances for six or seven hours every day.

Modjeska was fêted in London and reported with delight:

‘My success surpassed all my expectations; everyone here seems to think it quite extraordinary, and my manager has already numerous projects concerning my future.’2

The Prince of Wales visited her in her dressing room and she shared a stage with the great Genevieve Ward at a party given his honour; the two women got on famously. Lillie Langtry came backstage to meet her during a performance of Romeo and Juliet. Sarah Bernhardt, who Modjeska described as ‘the wonderful creature’, sent her a bouquet of white camellias and assured her that she was moved to tears by her performance. When Ellen Terry came to her dressing room, Modjeska declared:

‘Whoever has met Ellen Terry knows that she is irresistible, and I liked her from the first.’ 3

Offstage, Modjeska was embraced by fashionable society. She received an invitation to leading society hostess Lady Jeune’s unmissable ‘five o’clocks’. Wilde had once quipped:

‘There were three inevitables – death, quarter-day and Lady Jeune’s parties.’ (Quarter-days were the four days each year on which servants were hired, school terms started, and rents were due).

Keen to befriend this newfound star, Wilde invited Modjeska to tea. Her instinct was to refuse, since she thought it unwise to visit a young man unaccompanied, but she relented when he assured her that Lillie Langtry and artist Louise Jopling would be there too.

Before long, Wilde and Modjeska had become good friends. They collaborated on a poem, ‘Sen Artysty; or the Artist’s Dream. When it appeared in the Christmas 1880 edition of The Green Room, it was attributed to ‘Madame Helena Modjeska (translated from the Polish by Oscar Wilde)’. 4

Afterwards, Wilde enthused:

‘If there is any beauty in this poem it is the work of the subtle imagination and passionate artistic nature of Mme Modjeska. I myself am but a pipe through which her tones full of sweetness have flown.’

Wilde and Modjeska also considered adapting Verdi’s opera, Luisa Miller, but this project came to nothing and Modjeska left London to tour in the US and further afield

Helena Modjeska died at Newport Beach, California on April 8, 1909. She was 68 and had been suffering from Bright’s disease, a disease of the kidneys. Her remains were returned to Kraków where they were buried in the family plot at the Rakowicki Cemetery. Her autobiography, Memories and Impressions of Helena Modjeska, was published posthumously in 1910.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING:

1. As reported by G.K. Atkinson in The Cornhill Magazine 1925, Part 395, p.564

2. Helena Modjeska, ‘Modjeska’s Memoirs: The Record of a Romantic Career Part V, Success in London’, The Century Magazine, Volume 79, p.879

3. Modjeska, The Century Magazine, Volume 79, p.883

4. ‘Sen Artysty; or, The Artist’s Dream’ was published in Clement Scott (Ed.), The Green Room: Stories by Those Who Frequent It (London, Routledge, 1880), pp.66-8; http://www.helenamodjeskasociety.com/activity.html accessed on 12 January 2015