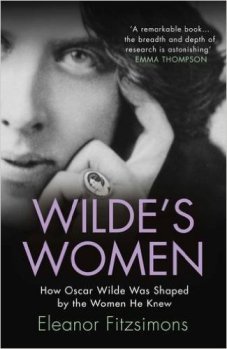

Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 6

October 4, 2016

Willie Wilde & Mrs Frank Leslie: An Unhappy Alliance

On the evening of 4 October 1891, Willie Wilde, aged thirty-nine, became the fourth husband of the formidable Mrs. Frank Leslie, a newspaper magnate who was sixteen years his senior. They hardly knew each other and were married at the aptly named Church of the Strangers in New York.

Mrs Frank Leslie

The New York Herald referred to the bride as ‘the well known publisher of this city’ and described the groom as ‘one of the editors of the London Telegraph and brother of Oscar’. Since Willie’s best man was humorist Marshall P. Wilder, Town Topics magazine took the opportunity to quip:

‘The groom was wild, the best man wilder, but the bride wildest of all.’

The quiet Sunday evening ceremony was followed by supper in Delmonico’s and a honeymoon at Niagara Falls, an apt choice in the light of Oscar’s quip:

‘Every American bride is taken there, and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life’.(1)

Mrs. Frank Leslie had been born Miriam Florence Folline in New Orleans on 5 June 1836. At seventeen, and under duress, she married jewellery shop clerk David Charles Peacock. Since they vowed to live apart for the remainder of their lives, it was perhaps inevitable that their marriage was annulled within the year.

Lola Montez

Afterwards, Miriam toured with the notorious Lola Montez, making up one half of the Montez sisters. During that time, she met husband number two, archaeologist E. G. Squier. When Frank Leslie hired Squier to edit his Illustrated Newspaper, he asked Miriam to fill in as editor of his Lady’s Magazine. She made a great success of it.

When he separated from his wife, Frank Leslie moved in with the Squiers and stayed for more than a decade before easing Squier aside to become Miriam’s third husband. When he died of throat cancer in 1880, Frank left Miriam a widow at forty-three and facing seemingly insurmountable debts.

She rose to the challenge, taking on and turning around her late husband’s ailing publishing company. She stamped her authority on the enterprise by changing her name by deed poll to ‘Frank Leslie’, the name he had assumed when he had established the business (he was born Henry Carter in Ipswich, England).

Yet, her creditors were circling and the whole enterprise would have foundered were it not for the intervention of Eliza Jane Smith, a wealthy widow and former housemaid who advanced Miriam a loan of $50,000 to be repaid over five years; it was returned within five months.

An accomplished linguist and frequent visitor to London for the season, Miriam attended Jane Wilde’s Saturday salons and attempted to emulate them with ‘Thursdays’ of her own. She was described by Jane as ‘the most important and successful journalist in the States’. In Social Studies, Jane elaborated:

‘She owns and edits many journals, and writes with bright vivacity on the social subjects of the day, yet always evinces a high and good purpose; and, with her many gifts, her brilliant powers of conversation in all the leading tongues of Europe, her splendid residence and immense income, nobly earned and nobly spent, Mrs. Frank Leslie may be considered the leader and head of the intellectual circles of New York.’

Jane and Miriam had much in common. Well schooled in literature and the classics, Miriam spoke French, Spanish, Italian, German and Latin. She, like Jane, had translated the work of Alexandre Dumas fils. In a gushing account of this transatlantic alliance, the New York Times described Jane as a ‘close and respected friend’ of Mrs. Leslie’s. The Los Angeles Herald reported that Miriam attributed her decision to marry Willie in no small measure to her ‘devotion to Lady Wilde’, while the Topeka State Journal quoted her as saying:

‘Lady Wilde is so charming that it had a great deal to do with my marrying her son, I think. I have tried to profit by her acquaintance, and hope some day to be in New York what she is in London.’

Members of the Lotos Club

Miriam had high hopes for Willie, but her plans to install him as a charming companion and lynchpin in her publishing empire came to nothing when it became clear that his preferred haunt was New York’s fashionable Lotos Club, frequented by Mark Twain amongst others. While his new wife worked tirelessly at the helm of her business, Willie could be found drinking, gossiping and reciting parodies of Oscar’s poems. One fellow Lotos Club member recalled:

‘You know, Oscar had a fat, potato-choked sort of voice,’ , ‘and to hear Willie counterfeit that voice and recite parodies of his brother’s poetry was a rare treat.’(2)

Another member remembered him as ‘the most thoroughgoing night owl that ever lived,’ and confirmed that he ‘positively hated daylight’.

The alliance was doomed. During a visit to London, Miriam hired a private investigator to report on Willie’s activities. Confronted with evidence of his boorish behaviour, she started divorce proceedings, charging him with drunkenness and adultery. When their marriage was dissolved on 10 June 1893, Judge C.F. Brown declared that Willie was:

‘addicted to habits of gross and vulgar intemperance, and to violent and profane abuse of and cruel conduct to the plaintiff’.(3)

Describing it as ‘a funny sort of match from the start,’ the Morning Call decided that their relationship would make a delightful social comedy and revealed that the bride had never altered her name, although ‘at times she would let “Wilde” be tacked on with a hyphen’.

Willie claimed, rather disingenuously:

‘The man who marries for money jolly well earns it’.(4)

When asked why he had married Miriam, his supposed reply was:

‘’Pon my soul. I don’t know. Do you? I really ought to have married Mrs. Langtry, I suppose’.(4)

Ironically, Miriam was said to have declared:

‘I really should have married Oscar’.(5)

Yet, after their divorce, she told a reporter from the Evening World:

‘I have only feelings of pity and sorrow for Mr. Wilde,’

adding,

‘I cherish no resentment towards him. He is a remarkably brilliant man of culture, but intemperance has demoralised him’.

She was even kinder about Jane, insisting:

‘Lady Wilde is one of the loveliest of women and extraordinarily intelligent, and there is still the best of feeling existing between us.'(6)

Wilde’s biographer and friend Robert Sherard believed that the marriage had been disastrous for Willie:

‘He went out to America a fine, brilliantly clever man, quite one of the ablest writers on the Press,’

he noted before observing that he came back to England

‘a nervous wreck, with an exhausted brain and a debilitated frame’.(7)

While she was married to Willie, Miriam felt a duty of care to her impoverished mother-in-law, and offered her an allowance of £400 a year. Jane, who was perhaps a little embarrassed at being financially dependent on another woman, would accept only £100, which she justified as the cost of maintaining a London home for the couple. Once the divorce was finalised, Miriam stopped Willie’s allowance, leaving him with no option but to join his mother in genteel poverty in her Oakley Street home. Poor Jane lived in constant fear of bailiffs arriving at her door to collect on Willie’s debts. When she cabled Miriam for help, her friend paid up grudgingly but broke with the family as a result.

Lady Jane Wilde in old age

In January 1894, six months after his divorce was finalised, Willie Wilde married Dublin-born Sophia Lily Lees. Although she had plenty of suitors, Miriam never married again. When she died in 1914, she left the bulk of her fortune to suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt in order that it be used for the promotion of the cause of women’s suffrage. A staunch champion of women’s rights, she once declared:

‘The old order is changing and the new coming. Woman must open her eyes to it and adapt herself to it, she must free herself from her swaddling clothes and go out into the world with courage and self-reliance. Oh, what a noble woman the woman of the future may become!’ (8)

She is undoubtedly one of Wilde’s Women.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING:

1. Oscar Wilde and Stuart Mason (Ed), Impressions of America (Sunderland, Keystone Press, 1906), p.25

2. From ‘Wilde and Willie’ by Nancy Johnson (archivist) in News and Notes from the Lotos Club, January 2011

3. ‘Mrs Leslie is Free’, The Evening World, 10 June 1893, p.3

4. Reported in The Nineteen-Hundreds by Horace Wyndham, p.76

5. Madeleine B. Stern, Purple Passage: the life of Mrs. Frank Leslie (Norman, Okla. Univ. of Oklahoma Press 1953 ), p.162

6. ‘Mrs Leslie is Free’, The Evening World, 10 June 1893, p.3

7. Sherard, Real Oscar Wilde, p.323

8. Included in Anne Commire, Deborah Klezmer, Women in World History Volume 9 (Waterford CT., Yorkin Publications, 1999), p.413

September 29, 2016

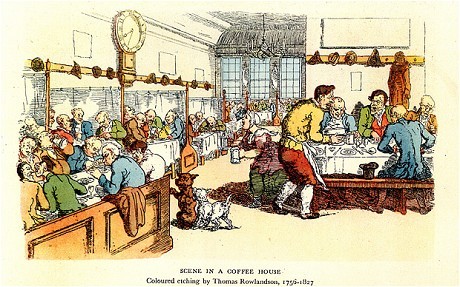

A Brief History of Coffee in London

The first coffee house in London was established in St. Michael’s Alley, Cornhill in 1652 by Pasqua Roseé, a man believed to have been born into the Greek community living in Sicily during the early years of the seventeenth century. He had first prepared this exotic beverage while working as a servant in Smyrna. Before long he was selling six hundred bowls of coffee a day; inevitably, his success attracted a good deal of competition. By the middle of the eighteenth century coffee houses had become an integral part of London life.

In 1728, a visiting Prussian nobleman, Baron Charles Louis von Pöllnitz, struck by their popularity, described the daily practice of visiting a favourite coffee house as ‘a Sort of Rule with the English,’ and observed that patrons ‘talk of Business and News, read the Papers, and often look at one another’.

The rapid growth in the popularity of coffee in London was due in part to the decision to tout it as an antidote to cheap and potent gin, the widespread availability of which had allowed drunkenness to grip the city.

An anonymous poem of the time hailed coffee as:

…that Grave and Wholesome Liquor,

that heals the Stomach, makes the Genius quicker,

Relieves the Memory, revives the Sad,

and cheers the Spirits, without making Mad.

Each coffee house reflected the character of its immediate neighbourhood, and offered exotic delights that included: Turkish coffee, sugar and cocoa from the West Indies, tobacco from Virginia, tea from China, and various chocolates and sherbets. One key attraction was the access such establishments facilitated to newspapers, scandal and the very latest in political gossip.

Many coffee houses doubled as places of business, doctor’s consulting rooms and gambling houses in many instances, and several patrons spent so much time in their favourite coffee house that they had their post redirected there. One such customer was Richard Steele, editor of The Tatler, who received his post at the Grecian off Fleet Street where he sourced much of the news that appeared in the pages of The Tatler too.

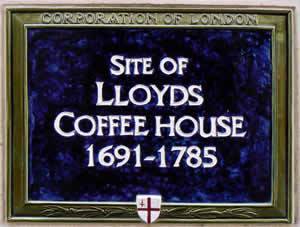

Several prominent coffee houses spawned new trades and occupations: Jonathan’s Coffee House in Change Alley operated as an embryonic stock exchange, displaying the prices of stocks and commodities on a board on the premises, while merchants, cartographers, ship-captains and stockbrokers developed the concept of insurance during long sessions at Edward Lloyd’s Coffeehouse on Lombard Street.

The Grecian Coffeehouse was popular with members of the Royal Society and, as a result, became a centre of learning. On one memorable occasion, a gathering of scientists that included Isaac Newton and Edmund Halley dissected a dolphin on a handy table, having cleared the used coffee cups off it first one hopes.

Enjoy your coffee!

September 21, 2016

Violet Hunt: The Sweetest Violet in England

Violet Hunt, born in 1862 in Durham in the north of England,was the daughter of Pre-Raphaelite landscape painter Alfred William Hunt and his wife, Margaret Raine Hunt, bestselling novelist and translator of the stories of the Brothers Grimm. Her parents took her to live in London when she was just three-years old and she grew up in Pre-Raphaelite circles. Violet was bright, vivacious and very beautiful. At thirteen, she was writing poetry for Century Magazine. Ellen Terry described her as ‘out of Botticelli by Burne-Jones’.

Violet Hunt

On one occasion, when Letitia Scott, wife of Margaret’s art tutor, William Bell Scott, invited Margaret, to come and meet ‘a wonderful young Irishman just up from Oxford’, she brought seventeen-year-old Violet along. Oscar Wilde, for it was he, flirted outrageously with Violet:

Beautiful women like you hold the fortunes of the world in your hands to make or mar,

he told her, adding conspiratorially:

We will rule the world – you and I – you with your looks and I with my wits.

Little wonder she thought herself ‘a little in love’ with him.

In her memoir, The Flurried Years (1926), Violet insisted that she had ‘as nearly as possible escaped the honour of being Mrs. Wilde’, adding:

I believe that Oscar was really in love with me – for the moment and perhaps more than a moment for Alice Corkran told me quite seriously that he had said to her quite seriously, “Now, shall I go to Mr. Hunt and ask him to give me little Violet?”

Oscar, who considered her, ‘the sweetest Violet in England’, called on the Hunts almost every Sunday for two years. When he went to America, Violet sought his mother out, hoping for news of her son:

Lady Wilde sits there in an old white ball dress, in which she must have graced the soirees of Dublin a great many years ago,

she wrote; she was not quite as sweet as she looked.

When Oscar returned from America with his hair freshly coiffed and curled, Violet decided he was, ‘not nearly so nice’ after all.

Although she adored the company of men, and described her life as ‘a succession of affairs,’ Violet Hunt never married. She would ‘snub eligibles on principle’, preferring married men since ‘no one could imagine that I wanted to catch them’. She could be terrifying: ‘I rather liked her,’ D.H. Lawrence admitted, adding: ‘She’s such a real assassin’.

Her many conquests included H.G. Wells, with whom she had an affair lasting a year when she was forty-four, and Somerset Maugham, but her most enduring love was for Ford Madox Ford; at thirty-six, he was eleven years her junior when they embarked on their lengthy affair. Violet’s once good opinion of Oscar may have been tainted by Ford’s dismissal of his writing as ‘derivative and of no importance’, although he did acknowledge ‘as a scholar he was worthy of the greatest respect’.

Violet Hunt & Ford Madox Ford

In later years, Violet remembered Oscar as:

…a slightly stuttering, slightly lisping, long-limbed boy, sitting in the big armchair at Tor Villa, where we lived then, tossing the long black lock on his forehead that America swept away, and talking – talking…

Oscar had always encouraged Violet to write. In time, she enjoyed an enviable reputation as a novelist, biographer and hostess of a thriving literary salon. Among her guests were Rebecca West, Ezra Pound, Joseph Conrad, Wyndham Lewis, D.H. Lawrence, and Henry James. Her interest in furthering the cause of women is reflected in the themes of her novels, the first of which, The Maiden’s Progress, was published in 1894. She joined the Women Writers’ Suffrage League in 1908, the year she helped Ford establish the English Review. Although she never published her memoir My Oscar, she did fictionalise him as fickle suitor Philip Wynyard in her semi-autobiographical novel Their Lives (1916).

When she died of pneumonia, aged seventy-nine, she left behind collections of poetry and short stories, seventeen novels, her memoirs of her time with Ford, a biography of Lizzie Siddal, six collaborations, two book translations, and numerous critical articles that were published in London newspapers and magazines.

Unlike that of many of her literary conquests, none of her work remains in print, although some of it is available to read online. Truly, she is one of Wilde’s Women.

Further Reading:

Violet: the story of the irrepressible Violet Hunt and her circle of lovers and friends – Ford Madox Ford, H.G. Wells, Somerset Maugham, and Henry James by Barbara Belford (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1990)

‘Aesthetes and pre-Raphaelites: Oscar Wilde and the Sweetest Violet in England’ by Robert Secor, Texas Studies in Language and Literature, Volume XXI, number 3 (Fall 1979)

The Flurried Years by Violet Hunt ( London, Hurst & Blackett, 1926), p.173

September 17, 2016

Culture Night 2016: Wilde & Women in The Arts

I was absolutely thrilled to be invited to participate in Ireland’s wonderful and vibrant Culture Night this year. I spoke at a brilliant event organised by herst_ry at the lovely Liquor Rooms on Dublin’s quays. My topic was how Oscar Wilde helped women in the arts. Here is a taste of just three of the women I spoke about. All three are included in my book Wilde’s Women:

Alice Pike Barney (1857–1931)

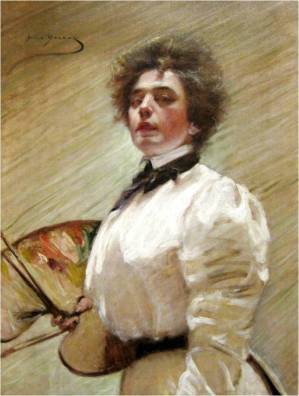

Self portrait: Alice Pike Barney doing what she loved best

One day in July 1882, Oscar Wilde took time out of his arduous lecturing schedule to go to the Long Island resort of Long Beach with one of his patrons Sam Ward. There he was introduced to Alice Pike Barney and her six-year-old daughter, Natalie. When Alice injured her foot in the water, Oscar, well over six feet tall and broad-shouldered, gallantly carried her up the beach and they got talking. Although hugely talented, Alice’s ambitions to study art were opposed by her boorish husband, Albert Clifford Barney, a hard-drinking man with a nasty habit of infidelity.

Oscar encouraged her to ignore her husband and so she did. She took art lessons in Paris and studied under Carolus-Duran and James McNeill Whistler. Later, she was admitted to the Society of Washington Artists and had solo shows at major galleries including the Corcoran Gallery of Art. With newfound confidence, she also wrote and performed in several plays and an opera, and worked to promote the arts in Washington, D.C. Many of her paintings are in the collection of the .

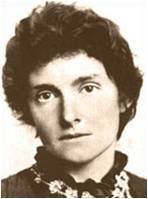

Elizabeth Robins (1862 –1952)

Elizabeth Robins: So much more than a beautiful face

American actress Elizabeth Robins was determined to break into English theatre. When she met Oscar at a party in July 1888, he told her: ‘Your future on our stage is assured’. He introduced her to influential theatre directors and even helped her to secure an agent. She found it amusing that he encouraged her to emulate Lillie Langtry since she saw herself as an altogether more serious performer with ambitions to manage and direct too.

The course of Robins’ life changed when she travelled to Norway and studied the works of Henrik Ibsen, a playwright who was sympathetic to the plight of women. In his notes for A Doll’s House, Ibsen asserted:

A woman cannot be herself in contemporary society; it is an exclusively male society with laws drafted by men, and with counsel and judges who judge feminine conduct from the male point of view.

Robins formulated a plan to introduce Ibsen to English audiences. She also hoped to end the stranglehold that male actor-managers had on English Theatre, a situation that resulted in women being undervalued as actors, writers and producers. When she struggled to attract subscribers to fund a series of twelve of Ibsen’s plays at the Opera Comique, Oscar stepped forward: ‘The English stage is in her debt,’ he declared, ‘I am one of her warmest admirers’. He funded her project and encouraged others to do so. Although audiences found the realism of Ibsen’s plays alarming, Oscar turned up several times and gave her productions his full attention. He assured her: ‘I count Ibsen fortunate in having so brilliant and subtle an artist to interpret him’.

Robins, grateful for Oscar’s support, acknowledged:

…he was then at the height of his powers and fame and I utterly unknown on this side of the Atlantic. I could do nothing for him; he could and did do everything in his power for me.

E. Nesbit (1858-1924)

E Nesbit; Pioneer of Children’s Literature

When Edith Bland, who wrote as E. Nesbit, sent Oscar her poetry collection Lays and Legend in 1886, he responded with an encouraging letter. As editor of The Woman’s World, he reviewed her collection Leaves of Life and published three of her poems. In his review of Woman’s Voices, an anthology edited by Elizabeth Sharp, he described Nesbit as ‘a very pure and perfect artist’, and lauded her ambition to ‘give poetic form to humanitarian dreams, and socialist aspirations’.

Nesbit, the main earner in her unconventional family, was obliged to all but give up writing poetry, her true passion, in favour of writing serialised children’s stories. Drawing on her own childhood fears and insecurities, she invented the children’s adventure story in which her protagonists faced genuine peril. Her best loved tales include the classics Five Children and It and The Railway Children. Nesbit changed children’s writing and influenced CS Lewis, JK Rowling and Jacqueline Wilson among many others. She is the subject of my next biography.

September 12, 2016

Oscar Wilde’s Father and the Campaign to Bring Cleopatra’s Needle to London

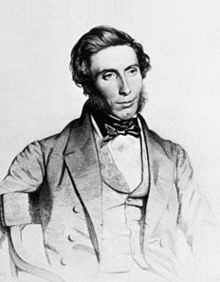

William Wilde as a young man

On 12 September 1878, one of of three Ancient Egyptian obelisks, popularly known as ‘Cleopatra’s Needles’, was erected on Victoria Embankment in London. Presented to the United Kingdom in 1819 by the ruler of Egypt and Sudan Muhammad Ali, in commemoration of the victories of Lord Nelson at the Battle of the Nile and Sir Ralph Abercromby at the Battle of Alexandria in 1801, this obelisk had remained in situ in Alexandria until 1877. It was then that Sir William James Erasmus Wilson, a distinguished anatomist and dermatologist, sponsored its transportation to London at great expense.

Almost four decades earlier, in April 1839, William Wilde, a Dublin-based surgeon and keen amateur Egyptologist and archeologist, who had travelled extensively throughout Egypt and beyond, wrote an article for the Dublin University Magazine in which he urged the British Government to transport one of these obelisks to London. It was lying in the sands, utterly neglected, and would, he suggested, make a fitting tribute to ‘the immortal Nelson’.

In his book Narrative of a Voyage to Madeira, Teneriffe and Along the Shores of the Mediterranean, which can be read online, he records his first encounter with the needles. Below is his article from the Dublin University Magazine in full, containing a detailed description of the obelisks along with practical suggestions as to how to transport them. Since William died in April 1876, with his sons, Willie and Oscar, and his wife, Jane, at his bedside, he never saw his scheme come to fruition.

September 10, 2016

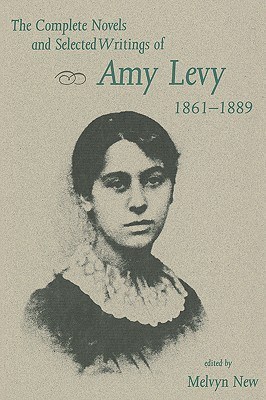

Amy Levy: ‘a touch of genius’

Amy Levy, born at Percy Place in Clapham, London on 10 November 1861, had a precocious talent. At 13, she won a junior prize for her criticism of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s proto-feminist epic Aurora Leigh; it was published in the children’s periodical Kind Words. Months later, her first poem, ‘Ida Grey: A Story of Woman’s Sacrifice’, was published in the moderate feminist journal The Pelican. Aged 17, she became the second Jewish woman to attend Cambridge University and the first to be admitted to the prestigious Newnham College. The fact that she left in 1881 without taking her degree may be an early indication of her troubled mind and poor sense of self-worth.

During her short career, she wrote political articles such as her letter, ‘Jewish Women and Women’s Rights,’ which revealed a liberal feminist ethos and was published in the Jewish Chronicle. She also completed three volumes of poetry, one published posthumously, and three very progressive novels, and she contributed pioneering journalism and brilliant short stories to several periodicals including Oscar Wilde’s Women’s World.

The best article in December 1887, Wilde told poet Louise Chandler Moulton, is ‘a story, one page long, by Amy Levy’. Levy had sent the story unsolicited. Recognising ‘a touch of genius’ in it, Wilde described her writing ‘as admirable as it is unique’ and commissioned a second story, two poems, a profile of the poet Christina Rossetti, and and article, ‘Women and Club Life’. Levy herself was a member of ‘A Men and Women’s Club’, a radical debating club founded by Karl Pearson, a socialist and a mathematics professor.

Although she had to all appearances, a successful and fulfilling life, Levy suffered from a desperately melancholic nature. She was hugely talented but desperately troubled and experienced debilitating bouts of depression exacerbated by failing physical health that she had experienced since childhood; she was partially deaf. Hailed as a pioneer of early lesbian writing, her own sexuality was never firmly established and she formed a close friendship with cross-gender writer Vernon Lee, born Violet Paget.

On the night of Monday, Sept. 9, 1889, two months short of her twenty-eighth birthday, Levy locked herself into a room at her parents’ house in Bloomsbury, blocked all possible sources of ventilation, and left a charcoal fire burning while she went to bed. She would have realised that the poisonous carbon monoxide fumes would be fatal, and she left instructions that she be cremated; she was the first Jewish woman in England to do so.

Wilde was dreadfully upset to learn of the death of this brilliant woman: ‘the world must forgo the full fruition of her power,’ he lamented in a heartfelt obituary that was published in The Woman’s World.

For more on Amy Levy, truly one of Wilde’s Women, read the very comprehensive timeline of her life on The Victorian Web here. Also, this article from Tablet Magazine here and her entry at the Jewish Women’s Archive here.

September 1, 2016

Adela Schuster: “one of the most beautiful personalities”

One of the lesser-known women in Wilde’s Women, someone who admired Oscar hugely is Adela Schuster, the extraordinarily generous daughter of a wealthy Frankfurt banker. She is thought to have met him late in 1892.

In 1895, when Oscar was in dire straits, Adela opened her purse to him; the £1000 she gave him paid his mother’s rent and her burial expenses as well as funding the confinement of Willie Wilde’s wife Lily. Adela also attempted to effect a reconciliation between Oscar and Constance by corresponding with mutual friends.

‘Cannizaro’, Adela Schuster’s Wimbledon home

In a letter to More Adey, written in 1896, Adela described the ‘real affection’ she felt for Oscar & her ‘immense admiration for his genius’, adding:

“I do and always shall feel honoured by any friendship he may show me…Personally I have never known anything but good of O…and for years have received unfailing kindness and courtesy from him – kindness because he knew how I loved to hear him talk, and whenever he came he poured out for me his lordly tales & brilliant paradoxes without stint and without reserve. He gave me of his best, intellectually, and that was a kindness so great in a man so immeasurably my superior that I shall always be grateful for it”.

Oscar in turn paid tribute to Adela in de Profundis, describing her as:

“…one of the most beautiful personalities I have ever known: a woman, whose sympathy and noble kindness to me both before and since the tragedy of my imprisonment have been beyond power of description: one who has really assisted me, though she does not know it, to bear the burden of my troubles more than anyone else in the whole world has: and all through the mere fact of her existence: through her being what she is, partly an ideal and partly an influence, a suggestion of what one might become, as well as a real help towards becoming it, a soul that renders the common air sweet, and makes what is spiritual seem as simple and natural as sunlight or the sea, one for whom Beauty and Sorrow walk hand in hand and have the same message.”

Oscar instructed Robbie Ross to make two copies of the letter that would become de Profundis, and to send one copy to Adela Schuster and one to Frances (Frankie) Forbes-Robertson, since he believed ‘both these sweet women will be interested to know something of what is happening to my soul’.

Although it’s not known whether Oscar met with Adela after his release, he did have a copy of The Importance of Being Earnest sent to her. On his death, she sent a wreath and her name was included on a list of “those who had shown kindness to him during or after his imprisonment,” attached to a wreath of laurels inscribed “A tribute to his literary achievements and distinction,” which was placed at the head of Oscar’s coffin by Robbie Ross

Ross also sent Adela a comprehensive account of Wilde’s final months on 23 December 1900, and dedicated The Duchess of Padua to her in his Collected Edition (1908) in order to fulfil Oscar’s desire to express his gratitude for her “infinite kindness”. His lovely dedication can be read here.

Truly, Adela Schuster was one of Wilde’s Women.

August 20, 2016

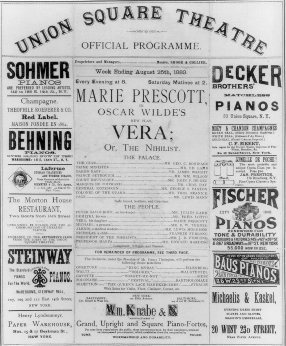

The Failure of Vera, Wilde’s First Play

Oscar Wilde’s first play, Vera, or the Nihilists opened in the Union Square Theatre on Broadway on 20 August 1883. The theatre was full on opening night and the audience included several actors and theatre managers whose productions had not yet opened.

Commentators were struck by the profusion of fans flapping ineffectually in front of the faces of overheated patrons; New York was wilting under the intensity of an enervating heat wave. Afterwards,the Spirit of the Times likened the Union Square Theatre to ‘the hottest room of a Turkish bath’.

Such stifling conditions could not have contrasted more markedly with the play’s setting: a frozen Russian winter that obliged cast members to don heavy brocade costumes, many of them fur-lined. While the audience struggled to cope with furnace-like heat, frozen peasants huddled around open fires onstage. It must have been impossible for overheated patrons to suspend their disbelief.

The plot of Vera centres on an insurgent cell led by the beautiful and principled Vera Sabouroff. In true melodramatic fashion, she falls desperately in love with her comrade Alexis, a sympathetic medical student, only to discover that he is the reforming son of the despotic Czar. Rather than assassinate Alexis, Vera plunges her dagger into her own breast to obtain the bloody proof demanded by her comrades, insisting that she is dying, not for love, but to save Russia.

The play started well. There were calls for the author after the first act and Oscar stepped forward to bow his thanks after the second. Although one intensely sentimental scene between Vera and Alexis during the melodramatic last act was greeted with laughter, catcalls and kissing noises from the cheap seats, Vera was generally well received and Oscar’s brief words of appreciation were applauded warmly.

Yet reviews for Vera were overwhelmingly disappointing. Describing it as ‘an energetic tirade against tyrants and despots…full of long speeches in which the glory of liberty is eloquently described’, the New York Times condemned the play as ‘unreal, long-winded and wearisome’. Its critic warned:

A dramatist…who puts a gang of Nihilists upon the stage, on the ground that they are interesting characters of the time and that their convictions make them dramatic, does so at his own peril.

The New York Herald described Vera as ‘long-drawn, dramatic rot, a series of disconnected essays and sickening rant, with a coarse and common kind of cleverness’. Its critic attacked Wilde as ‘not only a buffoon but a bore’. The New York Tribune insisted that Wilde’s play was:

…a fanciful, foolish, highly-peppered story of love, intrigue, and politics, invested with Russian accessories of fur and dark-lanterns, and overlaid with bantam gabble about freedom and the people. It was little better than fizzle.

Oscar’s brother Willie comforts him after the failure of Vera

There were notable exceptions: the New York Sun hailed Vera as a masterpiece, while the New York Mirror called the play ‘the noblest contribution to its literature that the stage has received in many years’. This latter publication whipped up controversy by claiming that a clique of theatre critics had conspired to crush Vera, declaring:

It has been the pleasure of the newspapers and that portion of the public which revels in its ignorance and flaunts its vulgarity to assail Mr. Wilde with every manner of coarse, cheap and indecent indignity.

With uncanny foresight, this newspaper declared: ‘It is not the first instance in history of the crucifixion of a good man on the cross of popular prejudice and disbelief’.

The play was cancelled before the end of its short run. Although far from Wilde’s best work, Vera is not a bad play. The reasons for the hostile reception it provoked, one of which was lead actress Marie Prescott’s troubled relationship with the American press, are documented in Chapter 9 of Wilde’s Women.

The play had already fallen foul of authorities in London and you can read about why here.

August 13, 2016

The Mystery of Oscar Wilde’s Maternal Grandfather

On the 13th August last, at Bangalore, in the East Indies, Charles Elgee, Esq., eldest son of the late venerable Archdeacon Elgee, of Wexford.

The last known record of Charles Elgee, maternal grandfather of Oscar Wilde, is an obituary that was published in the Freeman’s Journal on 4 February 1825. Charles had left the family home sometime earlier, a departure that obliged his wife Sarah (nee Kingsbury) to raise their three surviving children, Emily, John and Oscar’s mother Jane, alone. It was she who oversaw their education.

Charles and Sarah Elgee’s marriage was a turbulent affair and the early years, during which three of their four children were born (the third, Frances, died in infancy in 1815), were characterised by regular changes of address. Jane was born in 1821, towards the end of this unstable marriage, and evidence suggests that the family was living in County Wexford at the time. Certainly, this is stated as a fact in her obituary in The Guardian on Wednesday 12 February 1896, and The Times on 7 February 1886, and is often mentioned in local histories of the county.

Financial troubles may have contributed to the couple’s estrangement; a deed registered on 11 November 1814, granting Charles £130 from his wife’s inheritance to discharge his debts, contained an ominous clause in which he agreed not to touch his wife’s assets should they decide to separate. This was necessary, since, until the passing of the Married Women’s Property Act 1882, English law defined a wife as subordinate to her husband and stripped her of her legal identity.

It is not known why Charles travelled to India, although an obituary for his grandson and namesake, Charles Le Doux Elgee, son of John Kingsbury Elgee, which is included in the Report of the Secretary, Class of 1856, Harvard, suggests that he may have had ‘some connection with the East-India Company’.

Nothing further is known, by me anyway. Everything I have discovered is documented in chapter two of Wilde’s Women. Perhaps one of you can shed some light on this intriguing mystery?

July 20, 2016

New Book Deal: Biography of E. Nesbit

E. Nesbit

Some news! I’ve just signed a contract with Duckworth Overlook for book two, a biography of the brilliant and complex author E. Nesbit. I’m really excited about getting properly stuck in. Here’s the blurb from my agent’s website:

Edith Nesbit (1858-1924) is considered the first modern writer for children and a key influence for writers from C.S. Lewis to J.K. Rowling. Inventor of the children’s adventure story, her books remain hugely popular and are regularly adapted for stage and screen. A founder member of the Fabian Society and ‘a committed if distinctly eccentric socialist’, she railed against inequity, social injustice and state-sponsored oppression, incorporating her views into her books and influencing generations of children.

Described by George Bernard Shaw, one of a string of lovers, as ‘audaciously unconventional’, Nesbit’s unsettled childhood and vivid imagination conjured up fears and phobias that lasted into adulthood; she confronted them in the stories she populated with family, friends, lovers, and events from her life, often writing herself as twins – one brave, one retiring. A progressive woman, she cut her hair short and smoked incessantly. Yet, she never supported women’s suffrage and she remained loyal to her serially unfaithful husband, raising his live-in-lover’s children as her own.

This new biography, the first in more than two decades, will explore one of our most important writers in all her guises. Friends agreed ‘she could be morose as a gathering thundercloud…when she emerged – a sunburst!’ One described her as ‘wise – and frivolous; kind…and so intolerant’. She was intensely attractive to men and formed deep friendships with women too. Temperamental at times, she was also huge fun, always creative and often playful. Her parties were legendary, her ghost stories, terrifying, and her tales of adventure changed the world.

Publication (c) early 2018 all going well!