Eleanor Fitzsimons's Blog, page 10

March 1, 2016

Oscar Wilde & The Duchess of Padua

Oscar Wilde undertook to complete his second play, The Duchess of Padua, by this date (1 March) in 1883 and he signed a contract to that effect:

…a first class Five act tragedy to be completed on or before March 1st 1883 – Said tragedy to be the property of Miss Mary Anderson and her heirs forever.

In return, he was to receive $5,000, although just $1,000 was paid in advance with the balance falling due if, and only if, acclaimed American actress Mary Anderson approved his completed manuscript.

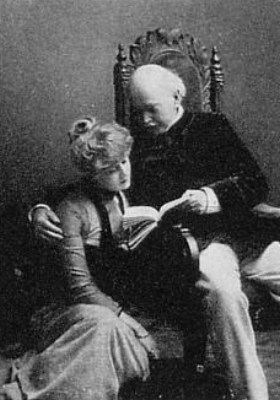

As Wilde had every expectation that his play would be accepted, he saw no reason to economise. He used Anderson’s advance to secure a suite of rooms on the second floor of the Hotel Voltaire, overlooking the Seine in Paris. When his friend Robert Sherard called on him, he saw evidence of industry scattered all about the living room; ‘a glance at these sheets showed that many of the lines had been written over and over again’, he recalled.

Wilde and Sherard, a great-grandson of poet William Wordsworth, met in Paris early in 1883 and got along exceptionally well. Since Sherard was estranged from his family and struggling to make a living as a writer, Wilde treated him to dinner at the celebrated restaurant in the Hotel Foyot. Making light of the cost, he declared: ‘we dine with the Duchess to-night’.

Robert Harborough Sherard

It’s thought likely that the contract between Wilde and Anderson was amended since he did not dispatch his completed manuscript until 15 March and he offered no word of apology. He following up with a long and exceptionally revealing letter outlining the approach he had taken to: ‘the masterpiece of all my literary work, the chef-d’oeuvre of my youth’. Noteworthy, at this early stage, is his absolute conviction that an element of comedy was essential in even the darkest tragedy, since no audience, he believed, would weep unless it was first made to laugh.

When Anderson turned the play down, Sherard was there to witness his friend’s muted reaction:

…he gave no sign of his disappointment. I can remember his tearing a little piece off the blue telegraph-form and rolling it up into a pellet and putting it into his mouth, as, by curious habit, he did with every paper or book that came into his hands. And all he said, as he passed the telegram over to me, was, “This, Robert, is rather tedious”.

To discover why Anderson rejected The Duchess of Padua, how Wilde exacted his revenge and whether the play was ever performed you’ll have to read Wilde’s Women.

Sherard, Real Oscar Wilde, p.218

February 25, 2016

Victor Hugo’s macabre tribute to Sarah Bernhardt

[image error]

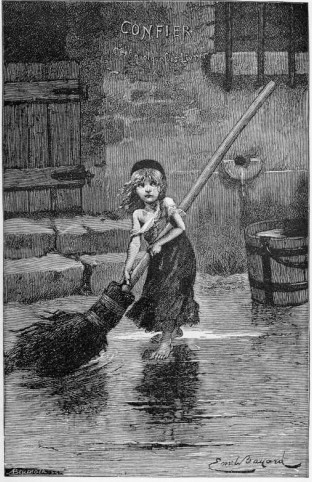

French novelist, poet, dramatist and accomplished artist Victor Hugo was born on this day (26 February) 1802. He shares a birthday with my brother, John Fitzsimons, who is also a very accomplished artist. We know Hugo best for his novel Les Misérables (1862), which has been adapted for stage and screen. You can read it here. Most of us (me included) probably assume that the iconic image of “Cosette“, which adorns a million T-shirts is a modern one. In fact it was drawn by French artist Émile Bayard for the original edition of Les Misérables.

Portrait of Cosette by Emile Bayard (1862)

Yesterday (25 February) was the anniversary of the première of Hugo’s historical drama Hernani, ou l’Honneur Castillan, an event that sparked riots between Romantics, drafted in by Hugo, and Classicists, who felt that their values were under attack.

The audience riots at the premiere of Hernani

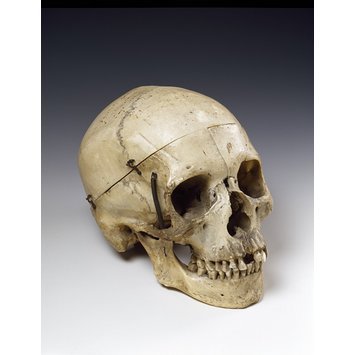

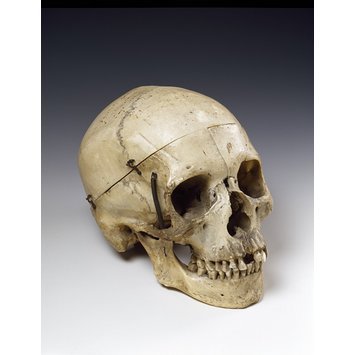

Decades later, in 1877, when French actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), one of Wilde’s Women, triumphed as Doña Sol, the woman central to the plot, Hugo presented her with a human skull. On it, he inscribed the words:

Squelette, qu’as tu fait de l’âme?

Lampe, qu’as tu fait de la flamme?

Cage déserte, qu’as-tu fait

De ton bel oiseau qui chantait?

Volcan, qu’as-tu fait de la lave?

Qu’as-tu fait de ton maître, esclave?*

Skull presented to Bernhardt by Hugo, which is in the V&A Collection, London

Bernhardt adored his macabre tribute, and used it as Yorick’s skull in the grave scene in Hamlet when she played the eponymous prince.

*Skeleton, what have you done with your soul?

Lamp, what have you done with your flame?

Empty cage, what have you done with

The beautiful bird that used to sing?

Volcano, what have you done with your lava?

Slave, what have you done with your master?

What do you give the woman who has everything? Hugo’s macabre tribute to Bernhardt

On this day (25 February) in 1830, Victor Hugo’s historical drama Hernani, ou l’Honneur Castillan had its première in Paris, an event that sparked riots between Romantics, drafted in by Hugo, and Classicists, who felt that their values were under attack.

The audience riots at the premiere of Hernani

Decades later, in 1877, when French actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), one of Wilde’s Women, triumphed as Doña Sol, the woman central to the plot, Hugo presented her with a human skull. On it, he inscribed the words:

Squelette, qu’as tu fait de l’âme?

Lampe, qu’as tu fait de la flamme?

Cage déserte, qu’as-tu fait

De ton bel oiseau qui chantait?

Volcan, qu’as-tu fait de la lave?

Qu’as-tu fait de ton maître, esclave?*

Skull presented to Bernhardt by Hugo, which is in the V&A Collection, London

Bernhardt adored his macabre tribute, and used it as Yorick’s skull in the grave scene in Hamlet when she played the eponymous prince.

*Skeleton, what have you done with your soul?

Lamp, what have you done with your flame?

Empty cage, what have you done with

The beautiful bird that used to sing?

Volcano, what have you done with your lava?

Slave, what have you done with your master?

February 23, 2016

When Nellie Melba met Oscar Wilde

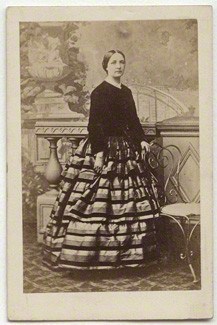

Dame Nellie Melba by Henry Walter Barnett

Australian operatic soprano Dame Nellie Melba, born Helen Porter Mitchell, died on this day (23 February) 1931, at the age of sixty-nine. As a young woman she was introduced to Oscar Wilde by their mutual friend Gladys, Countess de Gray, to whom he dedicated his play A Woman of No Importance. Although they never became close friends, and Nellie admitted that Oscar made her feel uneasy, she confessed to admiring his ‘brilliant fiery-coloured chain of words’.

They certainly met on several occasions and her description of his insatiable desire for cigarettes – she claimed that she knew he had called by the quantity of cigarette ends in her fireplace – suggest some intimacy and she qualifies as one of Wilde’s Women. On one occasion, Nellie recalled Oscar producing six cigarette cases from about his person, although he may have intended to gift them to his disciples.

Certainly, she knew something of his lifestyle. In her memoir, Melodies and Memories, she relates an anecdote about Oscar speaking to his sons ‘of little boys who were naughty and made their mothers cry’; one wondered aloud ‘what punishment could be reserved for naughty papas who did not come home till the early morning and made mothers cry far more’.

In Melodies and Memories, Nellie also writes of walking through Paris one day when Oscar lurched around a corner with a ‘hunted look in his eyes’. Her account describes how she was about to walk past when he stopped her: ‘Madame Melba – you don’t know who I am? I’m Oscar Wilde’, he said, perhaps assuming she did not recognise him, before continuing ‘I am going to do a terrible thing. I’m going to ask you for money’. Hardly able to look at him, she emptied her purse and in response, she says, he almost snatched the money, muttered his thanks and was gone.

As jdellevsen of wildetimes.net points out below, Wilde’s circumstances were desperate by then. It must have taken great courage to ask for help and he did so graciously. How unsettling it is to read this account of a great man brought so low.

Dame Nellie Melba (1861 -1931) celebrated operatic soprano and yet another fascinating example of one of Wilde’s Women.

My source for this article is: Nellie Melba. 1925. Melodies and Memories. Cambridge University Press

February 22, 2016

Dion Boucicault: pioneering playwright

On this day (22 February) in 1858, Jessie Brown, a play by Irish actor and playwright Dionysius (Dion) Boucicault premiered in New York City.

Dion Boucicault

While not immediately apparent from his exotic Huguenot name, Boucicault was born and brought up in Dublin. A contemporary of William and Jane Wilde, he was almost certainly the son of pioneering science writer and lecturer Dr. Dionysius Lardner, the lodger who had become his mother’s lover while her unwitting husband remained in the family home. As well as providing his forename, Larder supported Boucicault financially for the first years of his life and funded the completion of his education in England.

Aged seventeen and using the pseudonym Lee Moreton in order to thwart his mother’s opposition, young Dion embarked on a career in the theatre and enjoyed early success in London. Although his plays were profitable, he was an extravagant man and soon ran up insurmountable debts. In July 1845, when he was in his mid-twenties, Boucicault married Anne Guiot, a wealthy and considerable older French widow. He inherited her fortune after she died in an apparent mountaineering accident while she and Boucicault were holidaying in Switzerland a short time into their marriage. He was the only witness.

Before long, Boucicault was back in the debtors’ court and he was obliged to borrow money in order to pay for passage to New York for himself and Scottish actress Agnes Robertson, who would become the second of his three wives. There, he found success and wrote his most enduring play, The Colleen Bawn. For decades, Boucicault divided his time between London and New York, delighting audiences with his repertoire of original plays and adaptations of the work of others. He improved the lot of fellow playwrights by leading a campaign for the introduction of American copyright laws for original drama; he may have been the first playwright to receive a royalty rather than a fixed payment for his output.

Agnes Robertson

Boucicault took a keen and solicitous interest in the welfare of his compatriot Oscar Wilde. On reading his first play, Vera, the older man counselled: ‘You have dramatic powers but have not shaped your subject perfectly before beginning it’. He urged Oscar to convert his stilted dialogue into ‘action’ rather than ‘discussion’. In a letter to mutual friend Elizabeth Lewis, written while Oscar was touring America in 1882, Boucicault expressed alarm, writing: ‘He [Oscar] has been much distressed; and came here last night looking worn and thin’. In an amusing postscript, he suggested that, as well as securing better management, Oscar needed to ‘reduce his hair and take his legs out of the last century’ in order to find success.

Boucicault with Josephine Louise Thorndyke

While touring Australia in 1885, Boucicault, insisting that his marriage to Agnes, with whom he had six children, was invalid, married a young American actress named Josephine Louise Thorndyke. His reputation suffered as a result. Five years later, aged sixty-nine, he died in the arms of his new wife in New York city. In addition to leaving us his plays, he secured passage of the Copyright Law of 1856, developed fire-proof scenery, secured a profit-sharing system for playwrights, and established a foundation for actor-training. He also puts in an appearance in Wilde’s Women.

February 17, 2016

The Nihilist, the Czar & the cancellation of Wilde’s First Play

On this day (17 February) in 1880, Czar Alexander II of Russia survived an assassination attempt when the late arrival of Prince Alexander of Battenburg, guest of honour at a royal banquet, delayed dinner and ensured that the dining room was empty when a cache of dynamite concealed beneath it was ignited. This was the latest of several attempts on the Czar’s life. On 13 March 1881, the rebels succeeded and Czar Alexander II was fatally wounded while travelling under heavy guard in a closed carriage.

Czar Alexander II

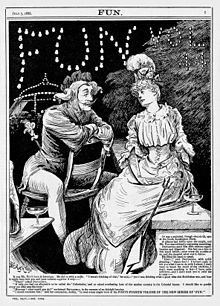

One unexpected outcome may have been the cancellation of a performance of Oscar Wilde’s first play, Vera, or The Nihilists, scheduled for the Adelphi Theatre on Saturday 17 December 1881. ‘I suppose everyone will be Russian to see it,’ a witty commentator had declared in the magazine Fun. He never got the chance to find out.

On 30 November 1881, a notice, possibly written by Oscar’s journalist brother, Willie, appeared in The World. It read:

‘Considering the present state of political feeling in England, Mr. Oscar Wilde has decided on postponing, for a time, the production of his drama Vera’.

Three days later, Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle provided the following information:

Mr. Wilde has admitted his play to a committee of literary persons, who have advised him to keep it from the stage. The work, composed about four years ago abounds in revolutionary sentiments, which it is thought might stand in the way of its success with loyal British audiences.

The plot of Vera centres on an insurgent cell led by the beautiful and principled Vera Sabouroff. In true melodramatic fashion, she falls desperately in love with her comrade Alexis, a sympathetic medical student, only to discover that he is the reforming son of the despotic Czar. Rather than assassinate Alexis, Vera plunges her dagger into her own breast to obtain the bloody proof demanded by her comrades, insisting that she is dying, not for love, but to save Russia.

Although Oscar changed the year to 1800 and relocated the action to Moscow, it is widely believed that Vera was inspired by twenty-two-year-old Vera Zasulich, who had attempted to assassinate General Fyodor Fyodorovich Trepov, Governor of St. Petersburg on 24 January 1878. Zasulich had much in common with Oscar’s Mother, Jane, who, in her youth,had agitated, albeit peacefully, for Irish independence. The educated daughter of a minor nobleman who died when she was three-years-old, Zasulich joined a group of insurgents in her late teens and her keen intelligence, combined with the Nihilist commitment to gender equality, propelled her to a position of leadership.

Vera Zasulich

On that January day, she joined a queue of petitioners seeking an audience with Trepov, before producing a pistol from under her cloak and shooting him with the intention of killing him. Although he survived, he was seriously wounded. Afterwards, Vera waited calmly to be arrested. She admitted her guilt without hesitation, but a sympathetic jury acquitted her. The international press, generally hostile to Nihilists, condemned her actions and her acquittal. An editorial in The Times declared: ‘We could have understood the trial if it had happened in Dublin’.

In contrast, the Dublin University Magazine, which counted Jane and Oscar among its contributors, carried a long and enthusiastic article praising her patriotic actions and condemning her mistreatment. Zasulich fled into exile, and turned her back on terrorism in order to pursue a socialist agenda.

The New York Times suggested that the cancellation of Vera was prompted by diplomatic communications from the Russian Government to Lord Granville, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.It was even rumoured that the Prince of Wales had intervened; the assassination of Czar Alexander II on 13 March 1881 made a Czarina of his Danish sister-in-law, Maria Feodorovna, Dagar of Denmark, who was married to the new Czar Alexander III.

Maria Feodorovna

Although Vera opened in New York in August 1883, the run was an unmitigated disaster – but that’s another story, one you can read in Wilde’s Women.

February 12, 2016

The Great Famine: Speranza Responds

Jane Wilde

In February 1847, the Great Famine in Ireland reached it’s height. The horror of this tragedy radicalised poet Jane Elgee, in her mid-twenties by then, prompting her to adopt the name ‘Speranza’ and write inflammatory poetry in response. Later, she would marry William Wilde and become the mother of Oscar. Here’s an excerpt from Wilde’s Women describing her response to the famine:

In 1847, Jane found a catastrophe to write about: Ireland’s rich soil yielded an abundance of high quality grain, meat and dairy products, and landowners sold the bulk of their produce overseas. When the price of grain became artificially inflated during the campaigns against the French, it was designated a cash crop for export. At the same time, the Irish population was growing inexorably, from five million in 1800 to in excess of eight million by 1841. The teeming families that farmed thousands of sub-divided smallholdings, half of them covering less than five acres, were required to survive on the potato crop alone. When the blight that ravaged America in 1842, crossed the Atlantic in the years that followed, the subsistence farmers of Ireland were hardest hit. Harsh governance and the laissez-faire trading policies adopted in Westminster exacerbated the problem, leading to famine in one of the most fertile countries in the world.

Jane’s words had a galvanizing effect: ‘a nation is arising from her long and ghastly swoon’, she declared. In ‘The Lament’, she gave voice to the Young Irelanders’ criticism of the increasingly ineffectual Daniel O’Connell: ‘gone from us…dead to us…he whom we worshipped’, she wrote. In ‘The Voice of the Poor’, she railed against the horrors of famine, writing, ‘before us die our brothers of starvation’; ‘The Famine Year’ condemned the arrival of, ‘stately ships to bear our food away’; ‘The Exodus’ lamented the ‘million a decade’ forced to flee their homeland. The most popular of Jane’s compositions was ‘The Brothers’, a rousing ballad eulogising Henry and John Sheares, one a lawyer, the other a barrister, both United Irishmen hanged for their part in the rising of 1798. In tone and theme it shares much with her son’s Ballad of Reading Gaol and it was taken up by the street balladeers of Dublin.

Snow lay deep when the famine reached its height in February 1847, and a typhus epidemic raged uncontrollably. The non-interventionist policies adopted by the newly installed Whig government were proving disastrous, and the soup kitchens and relief works set up to help the starving population were woefully inadequate. As the country headed inexorably towards insurrection, Jane’s contributions became increasingly provocative. Her poem, ‘The Enigma’ described how the living envied the dead as Ireland’s abundance was, ‘taken to pander a foreigner’s pride’. She lamented the loss of, ‘the young men, and strong men,’ who, ‘starve and die, for want of bread in their own rich land’.

When the offices of the Nation newspaper were raided in July 1848, editor, Charles Gavan Duffy was arrested and charged under the new Treason-Felony Act for publishing a newspaper article advocating the repeal of the Act of Union, a crime that carried the penalty of transportation. While he was in prison awaiting trial, he entrusted editorship of the Nation to his sister-in-law, Margaret Callan, aided by Jane. On 22 July the Nation carried Jane’s inflammatory poem, ‘The Challenge to Ireland’. The following week, she wrote an unattributed leader titled ‘Jacta Alea Est’(the die is cast); it was an unmistakable call-to-arms:

‘O! for a hundred thousand muskets, glittering brightly in the light of Heaven, and the monumental barricades stretching across each of our noble streets made desolate by England…’

As if this were not sufficiently treasonous, she beseeched:

‘Is there one man that thinks that Ireland has not been sufficiently insulted, has not been sufficiently degraded in her honour and her rights, to justify her now in fiercely turning on her oppressor?’

February 8, 2016

Elizabeth Bishop on Oscar Wilde

Today also marks the anniversary of the birth of poet, prose writer and translator Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and served as Poet Laureate of the United States.

Elizabeth Bishop

Of Oscar Wilde, she wrote:

‘One of my students lent me Oscar Wilde’s letters – a huge book. I just meant to glance at it but found myself still reading it at 4 A M today.’

Her verdict on the letters?

‘It gets sadder & sadder – but he [Wilde] was so funny – his US trip is marvelous – he drank all the miners in Colorado under the table (he was 25 or so) and they respected him very much in spite of his velvet knee-britches.’

I’m certain she would have been one of Wilde’s Women had she been born half a century earlier.

Source: Letter to Loren Frankenberg, January 8, 1972 referenced in Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil and After: A Poetic Career Transformed By George Monteiro

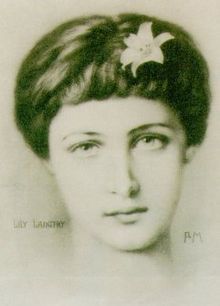

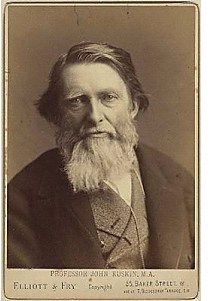

When Lillie Langtry Met John Ruskin

Today marks the anniversary of the birth of John Ruskin (1819-1900), Victorian art critic and social thinker, and a man who had a profound influence on art and life. Among his many admirers was Oscar Wilde, who met him at Oxford University and whose work and ideas were influenced by Ruskin’s thinking.

After he went down from Oxford University with a double first, Wilde headed for London where he somewhat reinvented himself as a socialite and took up with ‘professional beauty’ Lillie Langtry. Although his preoccupations often appeared trivial, from time to time he allowed Langtry to observe his true nature.

Portrait of Lillie Langtry by Frank Miles

When Wilde brought John Ruskin, then Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford, to call on Langtry at her home (some time around 1877-8), she noted that her normally convivial friend:

‘assumed an attitude of such extreme reverence and humility towards the “master” that he could scarcely find breath to introduce him to me’.

According to Langtry, this ‘unusually meek demeanor’ in her friend, ‘aggravated my natural shyness and filled me with exaggerated awe’. She was relieved to report that:

‘Ruskin’s winning voice and charm of manner reassured me, and, taking courage to look at him, I noted that his blue-grey eyes were smiling at me under bushy eyebrows.’

Langtry describes Ruskin further, noticing:

‘that his forehead was large and intellectual, that his nose was aquiline, and that the side-whiskers, made familiar by his earlier portraits, had become supplementary to a grey leonine beard’.

She goes on:

‘His hair was rather long, and floppy over his ears; indeed he was a shaggy-looking individual’.

As to Ruskin’s conversation, Langtry reports:

‘He held forth on his pet topic – Greek art – in a fervently enthusiastic manner, and as vehemently denounced the Japanese style, then at the beginning of its vogue, describing it as the “glorification of ugliness and artificiality,” and contrasting the unbalanced form of Japanese art with the fine composition and colour of Chinese art, of which he declared it to be a caricature’.

My source for Langtry’s fascinating reaction to Ruskin is her autobiography, The days I knew, p.140. For more on Langtry’s relationship with Oscar Wilde, why not read my Wilde’s Women.

February 7, 2016

Happy Birthday Charles Dickens!

Happy Birthday Charles Dickens, who was born on this day in 1812. He toured America several times and came into contact with a number of influential women who later championed Oscar Wilde.

Jane Tunis Poultney Bigelow

The first of these was the exuberant Jane Tunis Poultney Bigelow, an important figure in the New York literary scene and a woman who made it her business to cultivate the leading writers of the day. Bigelow’s correspondence with Wilkie Collins spanned two decades, and she had developed an interest in Dickens that bordered on an obsession. It was reported that, on one occasion, when Dickens was staying at the Westminster Hotel near Union Square in New York, an elderly widow called Mrs. Hertz prevailed upon the hotel manager, a friend of hers, to introduce her to him. As Mrs. Hertz was leaving the great writer’s room, Jane Bigelow allegedly accosted her and knocked her out.

When Jane’s diplomat husband, John Bigelow, co-editor and co-owner of the New York Evening Post served as Ambassador to Paris, newspapers described her as ‘a power in Parisian life … [who] enjoyed the attention and esteem of a woman, vivacious, witty, and intellectually vigorous’. When Bigelow was posted to Berlin, it was reported that Jane’s staunch insistence on the superior quality of American pork, led Bismarck to describe her as one of the brightest women he had ever met, and ‘eight Royal auditors’ to admit that American pork was ‘good enough for anybody’.* However, she was sometimes considered a liability, particularly when she allowed her servants to sit in the German imperial box at the opera.

In Florence, Bigelow called to pay her respects to novelist Ouida, only to hear her shout: ‘Tell Mrs. John Bigelow, of New York, that I don’t want to see her or any other American; I don’t like them’. Undaunted, as ever, she replied: ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself. We’re the only fools that read your nasty books anyway’. So thoroughly charmed was Ouida by her audacity that she invited Bigelow to stay for a month.

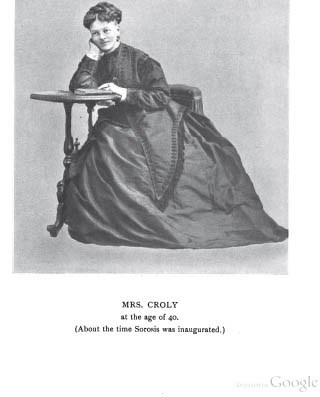

Back in New York in 1882, Jane Bigelow proved to be a loyal and useful ally to Oscar Wilde during his lecture tour of North America. Two additional women who feature in Wilde’s Women and had connections to both Dickens and Wilde are English-born Jane Cunningham Croly, better known by her pen-name ‘Jennie June’, and Kate Field, journalist, actress and campaigner for woman’s rights.

Croly was an exceptionally useful supporter to cultivate. Credited with pioneering and syndicating the ‘woman’s column’, she ran the women’s department at the New York World for ten years and was chief staff writer at Mme. Demorest’s Mirror of Fashions, later renamed Demorest’s Monthly Magazine. As ‘Jennie June’, she wrote ‘Gossip with and for Women’ for the New York Dispatch and ‘Parlour and Sidewalk Gossip’ for Noah’s Sunday Times. The sole breadwinner in her family, she juggled the responsibilities of motherhood and journalism by spending mornings at home before heading into the office at noon and working steadily until after midnight. Sunday nights were reserved for entertaining New York’s intellectual and artistic elite.

A passionate believer in networking for women, Croly founded the Women’s Parliament in 1856. She also established the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the New York Women’s Press Club. The elite members of her own New York Women’s Club campaigned for education, improved working conditions and better healthcare for women. She responded to the exclusion of women journalists, herself included, from an honorary dinner organised for Charles Dickens by the New York Press Club by founding Sorosis, America’s first professional woman’s club.

Kate Field

Field was nothing short of legendary; the New York Tribune described her as ‘one of the best known women in America’, while the Chicago Tribune called her ‘the most unique woman the present century has produced’. A popular lecturer and prolific travel writer, she wrote for several prestigious newspapers including the Chicago Times-Herald, the New York Tribune and the Boston Post. She was the inspiration for Henrietta Stackpole, Henry James’s crusading feminist journalist in The Portrait of a Lady. Extraordinarily well connected, she had hosted such luminaries as Charles Dickens, Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Eliot, Anthony Trollope, and Mark Twain. Although she knew Dickens well and had covered his final American tour for the New York Tribune, Field too was barred from the Press Club dinner that honoured him, a snub that prompted her to assist Jane Croly in founding Sorosis.

* Reported in the Daily Inter Ocean, Illinois, 11 Feb 1889, page 5