David Gibbins's Blog, page 8

February 6, 2015

Blending fact with fiction: David Gibbins on wreck diving

Click here to read this blog on my publisher Headline's website.

David Gibbins diving on the wreck of the SS Grip, Cornwall, October 2014

February 3, 2015

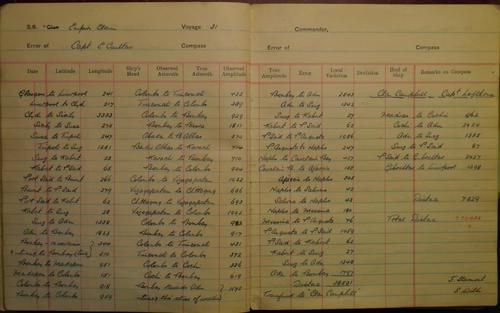

SS Clan Macnair, convoy SL-74 and the sinking of the Bismarck, May 1941

Clan Macnair in the Mersey off Liverpool, photographed before the war.

The last certain photo of HMS Hood, taken from HMS Prince of Wales on the morning of 24 May 1941 shortly before Hood blew up and sank with all but three of her 1,418 crew (Imperial War Museum, HU S0190).

When the German battleship Bismarck put to sea on 19 May 1941 on her one and only offensive mission, ‘Operation Rheinubung’, she carried a boosted complement of sailors to provide prize crews for the many Allied merchant ships she was expected to capture. The naval action that followed, the most momentous of the war against Nazi Germany, is remembered for the relentless determination of the Royal Navy to pursue and sink Bismarck at whatever cost, spurred by the desire to revenge the sinking of HMS Hood in the Denmark Strait on 24 May. The drama and horror of those eight days – the sinking of the pride of the Royal Navy with all but three her 1,418 crew, and then the final destruction of Bismarck with even greater loss of life - overshadows the fact that Bismarck and her escort Prinz Eugen had left port not to engage the Royal Navy, but to wreak havoc among Allied merchant shipping in the North Atlantic. On the day of her departure there were eleven convoys at sea with striking distance, comprising hundreds of merchant vessels as well as troopships carrying Canadian soldiers to Britain. Had Bismarck been able to get among a single one of those convoys, her eight 15-inch guns could have wrought destruction far worse than the most devastating U-boat attacks. Revenge for Hood may have hardened the resolve of the Royal Navy, but behind the pursuit lay a fear among British commanders of a calamitous loss of foodstuffs, military supplies and troops at a time when the course of the war lay very much in the balance.

Like many of my generation fascinated by naval history I grew up haunted by the sinking of Hood, a feeling reawakened when her wreck was discovered in 2001 off Greenland and the first ghostly images were shown of her twisted remains, and of sailors’ boots lying among debris on the seafloor almost 3,000 metres deep. I was fascinated too because my grandfather was one of the many merchant seamen on the Atlantic during those months when Bismarck was such a threat; he had returned to the UK as Second Officer of the cargo ship SS Clan Murdoch in March 1941 and set off again in SS Clan Macnair in June, just after she had returned with convoy SL-74 from Freetown in West Africa. SL-74 had been the closest convoy to the Bismarck at the time of her sinking, and it was the convoy’s main escort, the cruiser HMS Dorsetshire, that delivered the torpedo attack widely regarded as the coup de grace that finished the Bismarck.

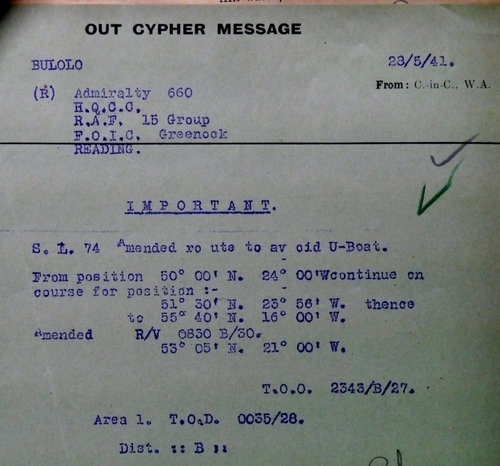

While I was in the UK National Archives researching my grandfather’s subsequent ship, Empire Elaine (see here), I discovered that the convoy record for SL-74 (ADM 237/1187) survives intact, including the convoy commodore’s report, his narrative and the decrypted cypher messages sent to the convoy during its passage. The documents reproduced below have never previously been published, to my knowledge, and provide a fascinating addendum to the mass of documentary material in the National Archives on the sinking of Hood and Bismarck and the aftermath.

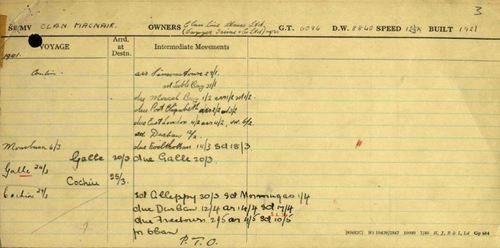

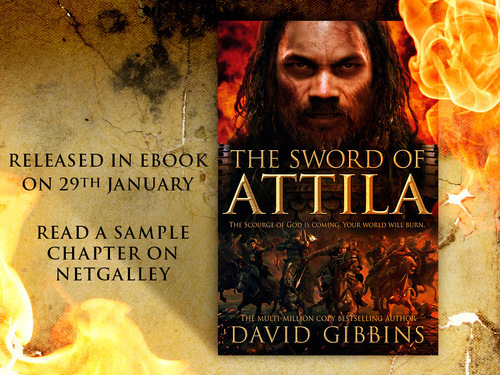

The Ship Movement Card for Clan Macnair showing her departure from Freetown on 10 May 1941 in convoy SL-74 (an unusual detail, as the cards rarely identify convoys) (UK National Archives).

Clan Macnair, a 6,078 ton general cargo ship built in 1921, was on the last leg of a voyage that had taken her to India and South Africa; she left Freetown in on 10 May 1941 as one of 43 merchant ships forming convoy SL (Sierra Leone) 78, bound for Oban in Scotland. The convoy had only two escorts, HMS Bulolo, an Armed Merchant Cruiser, and HMS Dorsetshire, a heavy cruiser with a crew of more than 650. New of the loss of Hood left the crew of Dorsetshire ‘devastated’ and filled with ‘remorseless determination to get revenge’ (quotes from crew in Iain Ballintine, Killing the Bismarck, 2014, p 131). The loss of life was so great that many seamen, both Royal Navy and merchant, knew people on Hood; in my grandfather’s case it was one of his classmates from 1923-5 on the training ship HMS Conway, Edward Lewis, who had opted for Royal rather than Merchant Navy service and was a Lieutenant on Hood at the time of her sinking. After contact had been lost with Bismarck, there must have been considerable apprehension in convoy SL-74 that Bismarck’s likely course, south-east across the Atlantic, would cross their own, at a point that would turn out not far to the west of Bismarck’s final position some two hundred miles north-west of Cape Finisterre in Spain.

The 'Short Narrative' of convoy SL-74 by the convoy commodore, Commodore Brook, R.N.R., including mention of the departure of Dorsetshire and then her part in the sinking of Bismarck, May 26-7 (UK National Archives, ADM 237/1187)..

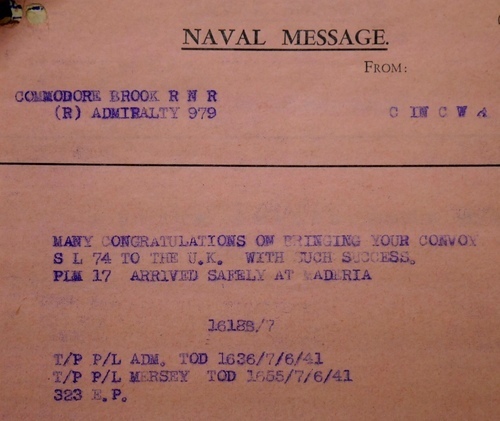

The final message in the record for SL-74 showing the convoy split as it approached the UK, with the second group, including Clan Macnair, destined for Oban (UK National Archives, ADM 237/1187).

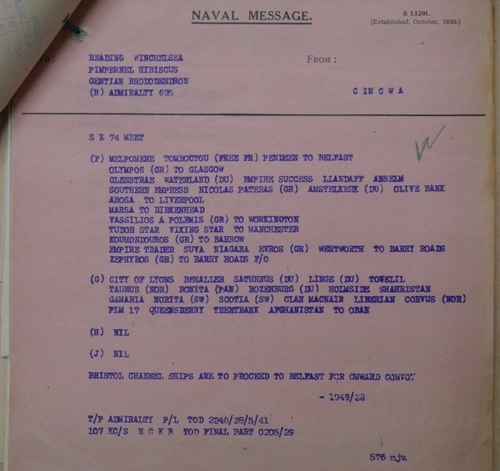

At 1035 on 26 May an RAF Catalina flying boat signalled the position of a mystery ship that could only be the Bismarck, some 700 miles west-northwest of Brest and heading south-east towards Cape Finisterre. 25 minutes later the report reached convoy SL-74, at that point some 600 miles west of Cape Finisterre and 300 miles south of Bismarck’s reported position. Mindful of the possibility that the pursuing British capital ships might be too far behind and that Bismarck might reach a German-held port in the Bay of Biscay, Captain Martin of Dorsetshire decided to leave the convoy and sail north-east on a converging course with Bismarck. He would have known that Dorsetshire with her 8-inch guns would have been overwhelmed by Bismarck, but he would have hoped that she might inflict enough damage to slow Bismarck down in time for the other ships to arrive. In the event, the main British force did, of course, catch up with Bismarck, though it was Dorsetshire’s torpedoes that delivered the final blow. Meanwhile, convoy SL-74 escorted only by Bulolo crossed over the wake of Bismarck less than a day after she had passed that point, the convoy’s position on the following day being pinpointed by the cypher message reproduced below ordering a course change to avoid U-boat attack.

HMS Dorsetshire before the war (Imperial War Museum, Q 65701).

The actions of Captain Martin of Dorsetshire have come under much scrutiny, for two main reasons. The first was his decision to leave convoy SL-74 on the morning of 26 May and join in the pursuit of the Bismarck. He had not been ordered to do so, and by departing he left the convoy virtually undefended. His decision was unquestionably a huge risk to his own career, with the certainty of court-martial had any one of those ships in the convoy been lost or damaged by enemy attack. However, there is no hint of censure for his action by the convoy commodore, and instead one can detect a sense of satisfaction in the commodore's note on the following day that news had been received of Bismarck’s destruction by Dorsetshire herself, thus associating the convoy with this momentous event.

The last known photograph of Bismarck, shells falling around her and trailing smoke, taken from the railing of a British ship on 27 May 1941 (Lt J.H. Smith, RN, IWM A 4386).

In fact, even when Dorsetshire had been present, the convoy had been poorly defended, the heavy cruiser being less able to pursue and depth-charge U-boats than the corvettes and destroyers that escorted the north Atlantic convoys. The inadequate defence of the West African convoys was a constant issue through the war. After Clan Macpherson was sunk in May 1943 in Convoy TS-37, for which the escort was only one corvette and three armed trawlers, her Master, Captain Edward Gough, made an official complaint about the weakness and slow speed of the escorts as well as the lack of air cover. The Director of the Trade Division in the Admiralty replied that ‘The U-boat threat … off the West African coast is but a fraction of that in the North Atlantic and we obviously must allocate our limited resources in escort vessels accordingly. Were it possible, there is nothing we would like better than to give every convoy a really strong escort’ (quoted by Gordon Holman in the official history of the Clan Line during the war, In Danger’s Hour, Hodder and Stoughton 1948, p 134). This would have been little consolation for the survivor of a convoy which had been hit so hard - Clan Macpherson was one of seven ships sunk from TS-37 by a single U-boat, U-515, over the space of two days.

The second criticism of Captain Martin of Dorsetshire concerns his decision to break off the rescue of Bismarck survivors because of a perceived U-boat threat in the area of the sinking. By leaving convoy SL-74 the day before to intercept Bismarck and be in at the kill he had also committed his crew to one of the horrors of naval warfare, of having to abandon fellow mariners – albeit the enemy – to certain death in the water. The strenuous attempts by Dorsetshire’s crew to rescue Bismarck survivors are well-known, as well as the uncertainty over the alleged U-boat sighting (see Ballintine’s Killing the Bismarck, referenced above, p 198-9).

Convoy SL-74, UK National Archives ADM 237/1187).

The cypher message reproduced here to Bulolo on the following day, 28 May, indicating the course change for convoy SL-74 ‘to avoid U-boat’, would appear to strengthen the evidence for a threat in the area. One U-boat, U-74, is known to have surfaced at the site of the sinking after the British warships had left, and picked up three remaining survivors. Either that or another U-boat in the vicinity could have made its way north-west in the hope of attacking the nearest convoy, SL-74, though in the event failing to make contact as a result of the convoy’s course being altered. Whatever the truth, the cypher message bolsters the case that Captain Martin of Dorsetshire had good grounds to leave when he did, however grim the consequences for those of Bismarck's crew still alive in the water.

Of the Royal Navy ships mentioned here, HMS Bulolo survived the war – she was again to escort one of my grandfather’s ships, Empire Elaine, in the Indian Ocean in 1944, before serving as Headquarters Ship off Gold Beach during the Normandy landings. However, both Prince of Wales and Dorsetshire were to be sunk in separate incidents by Japanese aircraft within a year of the Bismarck action, with the loss of more than 500 crew between them. Of the merchant ships in convoy SL-74, seventeen were to be lost to U-boats by the end of the war. Of the many ships sunk in subsequent SL convoys, one of the worst hit was SL-76, only a month after the Bismarck action, when 8 ships of the convoy were sunk within the space of two days by U-boats off west Africa, similar to the losses two years later noted above in convoy TS-37 off the same stretch of coast. Soon afterwards in July 1941 my grandfather was in Clan Macnair plying the same waters south, in a convoy that by chance failed to attract the attention of the same U-boat pack.

Convoy SL-74, UK National Archives, ADM 237/1187).

The most poignant of the communiques in the convoy dossier for SL-74 is the message of congratulations from the Admiralty to the convoy commodore for bring all of his ships in safely. The survival of the men in that convoy was due to luck, to the reduced U-boat activity against convoys during Operation Rheinubung, and above all to the skill and tenacity of the Royal Navy sailors who fought and destroyed the Bismarck, including the 1,415 men who went down with HMS Hood.

Clan Macnair post-war, with her peacetime paint scheme and extended funnel. She was scrapped in 1952.

January 26, 2015

THE SWORD OF ATTILA: Hun Blitzkrieg

Click here to read my blog on the Macmillan website comparing the Hun advance of the 5th century AD with the Nazi blitzkrieg of the Second World War.

Huns at the Battle of Chalons (the Catalaunian Plains), by Alphonse de Neuville (1835-1885).

Hun Blitzkrieg

Click here to read my blog on the Macmillan website comparing the Hun advance of the 5th century AD with the Nazi blitxkrieg of the Second World War.

Huns at the Battle of Chalons (the Catalaunian Plains), by Alphonse de Neuville (1835-1885).

January 25, 2015

M.V. Empire Elaine and Operation Bullfrog, the cancelled 1944 seaborne assault on Burma

Burma Star, awarded to Captain L.W. Gibbins for operations in the Bay of Bengal, 1944

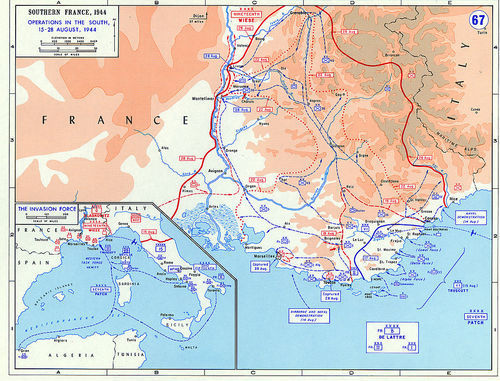

This is my fourth blog on the British assault ship Empire Elaine and my grandfather’s experience as her Second Officer under Combined Operations, the British naval command responsible for seaborne landings during the Second World War. Empire Elaine had been designed for the Ministry of War Transport (M/T) as an L.S.C. (Landing Ship Carrier), one of few heavy-lift ships purpose-built to carry L.C.M.s (Landing Craft Mechanised). Despite her military role, the crew of Empire Elaine - in common with other M/T ships - were drawn from the Merchant Navy and managed by a shipping company, in this case the Clan Line. In my previous blogs I’ve written about Empire Elaine’s role in Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in July 1943, and Operation Dragoon, the invasion of the South of France in August 1944; here I’m looking at the period between those operations when she was in the Indian Ocean, another case where the primary documentation for her activities is elusive because of the top-secret nature of all actions planned by Combined Operations during the war.

Before his death in 1986 my grandfather spoke to me about some of his experiences in the eastern war zone, in particular the severe monsoon conditions that forced Empire Elaine back to Bombay during her first attempt to sail west to Suez and back to the Mediterranean in July 1944, in preparation for Operation Dragoon the following month. As a peacetime officer with the Clan Line – arguably the last of the great East Indies shipping companies – my grandfather had an intimate knowledge of the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal, and Clan Line men knew as well as any others the dangers of these waters during the war, with three ships managed by the company being lost to U-boats in the Indian Ocean in 1943-4 - Clan Macarthur, Banffshire and Berwickshire – and with Japanese air, mine and submarine attack also taking a toll of Allied shipping there and in the Bay of Bengal.

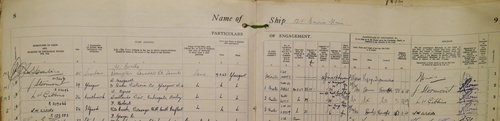

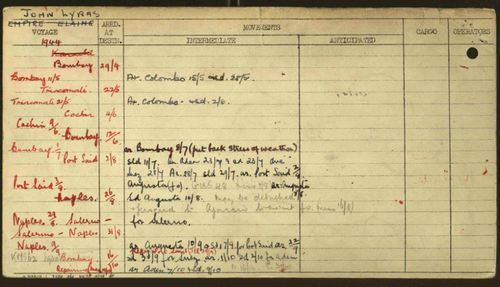

Years after my grandfather’s death I found a copy of the official history of the Clan Line during the Second World War, Gordon Holman’s In Danger’s Hour (Hodder and Stoughton, 1948), with a report from Empire Elaine’s master, Captain Ernest Coultas, showing that after Sicily she had ‘… been on special service in the Indian Ocean, had carried an 85-ton tug and many landing craft to ports in the Eastern war zone,’ and had ‘run through the monsoon’ before returning to the Mediterranean for the South of France landings (p. 194). As with the Mediterranean operations, my first point of reference when I came to revisit my grandfather’s experiences was his personal distance log showing ports-of-call and mileages during that voyage. The excerpt below shows Empire Elaine’s entire voyage from Sicily through various ports in the east Mediterranean to Suez and then to Bombay, and after that a complex itinerary of short- to medium-haul voyages from Bombay to Ceylon and back, and north to Iraq and Persia, with his telling note after the first arrival in Bombay ‘on exercises and returning to Bombay (twice)’:

The Ship Movement Card, the official summary of a ship’s movements now kept in the UK National Archives, gives little away, apart from confirming a number of the port visits and their dates, and showing that – as with the Sicily operation – Empire Elaine continued to be ‘Allocated to S.T.A.6A, for the carriage of special military cargo.’ More clarification is given by Arnold Hague’s convoyweb, which allows Empire Elaine’s convoys and port arrivals and departures to be traced through the war. Although a secondary source, these convoy records are corroborated by everything I have seen among the primary documentation, including my grandfather’s log. They show that after having sailed independently from Aden on 9 September and arriving at Bombay on 16 September 1943, there is a two month gap before the convoy records show her departure from Bombay again, on a voyage to Colombo in Ceylon in 19 November. Another gap of a month occurs between the date of her return to Bombay on 21 December and her departure again for Colombo on 14 January 1944. The first of these gaps coincides with my grandfather’s note in his log, about being on exercises. The second is explained by the following entry in the Admiralty War Diary in the UK National Archives, noting Empire Elaine:

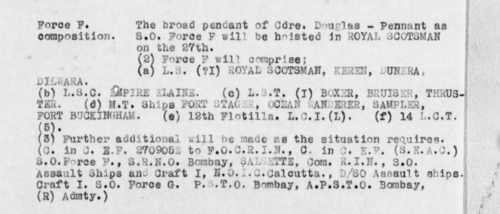

This entry explains the ‘exercises’ and proves that Empire Elaine was one of many vessels being assembled in the Indian Ocean in preparation for Operation Bullfrog, the codename for a planned assault on the Arakan coast of Burma in early 1944. The primary source material for the operation can be found in the UK National Archives by searching Operation Bullfrog, including ADM files on the naval planning. The objective, seen in the map below, was to land a division at Akyab Island (now Sittwe) at the base of the Mayu Peninsula, with the aim of cutting off the Japanese 55th Division as they advanced towards 15th Indian Corps to the north-west. Of the vessels listed with Empire Elaine in Force F, HMS Keren, HMS Denera and HMS Dilwara were troopships converted to L.S.I.s (Landing Ships Infantry), and HMS Boxer, HMS Bruiser and HMS Thruster were L.S.T.s Landing Ships Tank). Many of these ships had participated in the Sicily landings in July 1943 and the Salerno landings two months later (among her other achievements, HMS Boxer transported the comedian Spike Milligan from Africa to Italy with his artillery battery, as recounted in his 1978 autobiography Mussolini: His Part in My Downfall). Operation Bullfrog would therefore have been their third and possibly their most hazardous assault landing in only six months, had it not been cancelled in January 1944.

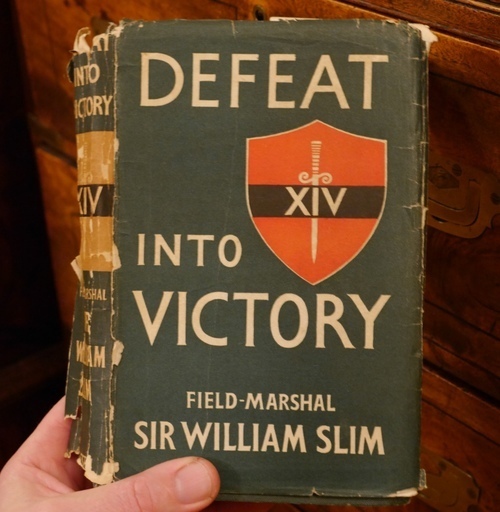

The circumstances of the cancellation are recounted in his book on the Burma campaign by General Bill Slim, the commander of 14th Army in Burma and one of the best generals of the war. My daughter’s maternal grandfather, a wartime officer in 4/15 Punjab Regiment, served under him as an intelligence officer during the retreat from Rangoon in 1942, and I have his well-thumbed copy of Slim’s Defeat into Victory with me now. In it Slim bluntly described a seaborne landing in Burma in early 1944 as ‘the correct strategy’, the linchpin of a seven-pronged offensive operation approved by the Combined Chiefs of Staff at their Cairo conference in late November 1943. Unfortunately for Slim’s plans, only days later at the Tehran Conference Stalin insisted that he would only commit Soviet forces to the war against Japan if all efforts were directed first at defeating Germany. Churchill and Roosevelt accepted the condition, and ‘more than half the amphibious resources of South-East Asia were directed back to Europe’ (Slim, ibid., 213).

The consequence for Empire Elaine is recorded in the Admiralty War Diary of 26 February 1944: ‘S.A.C.S.E.A. (South East Asia Command) reports that the broad pendant of Commodore Douglas-Pennant as S.O. Force F was struck at sunset on 9th February and the Force disbanded.’ Tellingly, the very next entry reports news from the Arakan, revealing just the outcome that Slim had feared: ‘Heavy fighting is going on in the Arakan where the Japanese troops are attacking with the object of taking Chittagong.’ It was to Chittagong – the Allied supply port close to the Burma border - that Empire Elaine next went, carrying landing craft. Chittagong was under constant threat of air attack, and by the date of Empire Elaine’s arrival, 5 April 1944, the Japanese offensive into India was in full swing and the desperate battles of Imphal and Kohima were being fought to the north-east beyond the border in Assam. For the crew of Empire Elaine, sailing the last leg of the journey as a single-ship convoy from Calcutta to Chittagong, the perils of submarine attack would probably have been uppermost in their minds, even in a place so far from the main German U-boat threat. On the same Calcutta-Chittagong route less than two weeks earlier the Japanese submarine RO-111 had sunk the troopship El Madina, with 380 killed - an event horribly reminiscent of the torpedoing only a month before that off the Maldives by another Japanese submarine of another troopship, the Khedive Ismael, with the loss of almost 1300 soldiers and crew, one of the worst British maritime disasters of the war.

Map showing ambhibious operations undertaken by the Royal Indian Navy in 1945, including the landings at Akyab on 3 January - site of the cancelled Operation Bullfrog landings of a year earlier. Chittagong lies on the Indian coast at the top left corner. (From The Royal Indian Navy, 1939-45, part of The Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War).

Only days after the disbanding of ‘Force F’, one of the M/T ships, Fort Buckingham, also came to grief, torpedoed on 20 January 1944 by U-188 off the Maldives on her way back to the Atlantic, with the loss of her Master, Captain Murdo Macleod, D.S.C., thirty crew and seven gunners. Most of the other ships returned to the Mediterranean, some speedily enough to take part in the Anzio landings in Italy that month, and many to take part – along with Empire Elaine – in Operation Dragoon in August. At the time, the frustration shown in General Slim’s account must have clouded feelings about the time and effort spent preparing for Operation Bullfrog, but the additional experience and training it provided undoubtedly paid rewards. Commodore (later Admiral Sir Cyril) Douglas-Pennant was next to ‘hoist his broad pennant’ in HMS Bulolo – a ship well-known to my grandfather from a convoy earlier in the war, one that narrowly avoided an encounter with the German battleship Bismarck – when Douglas-Pennant commanded the assault force at Gold Beach in Normandy, on D-Day, 6 June 1944.

By the time that coastal units of the Royal Indian Navy finally landed at Akyab Island, on 3 January 1945 – possibly using landing craft disembarked at their base at Chittagong by Empire Elaine ten months earlier – the Japanese had melted away from the Mayu Peninsula, and the assault troops joined the rest of 14th Army under Slim on their relentless push towards Rangoon and victory in Burma. Whether Operation Bullfrog would have inflicted an earlier, decisive defeat on the Japanese, saving the thousands of lives lost at Imphal, Kohima and the other battles of 1944, or whether the landings would have exacted too high a price on the men and ships involved, can never be known.

January 23, 2015

Audiobooks: the complete series, ATLANTIS to PHARAOH

Here's the complete series of CD Audiobooks of my novels from Atlantis to Pharaoh, read by James Langton. All are available from Amazon.com.

January 9, 2015

THE SWORD OF ATTILA

If you're on NetGalley, you can read a sample of the first three chapters of my new Total War novel THE SWORD OF ATTILA here: https://www.netgalley.com/catalog/show/id/59022

December 17, 2014

M.V. Empire Elaine, convoy KMS 18B and Operation Husky, 10 July 1943

Assault ship Empire Elaine on the Clyde in early 1943, being refitted and repainted in preparation for Operation Husky.

In my last blog I presented a range of primary documentation for the involvement of my grandfather Captain L.W. Gibbins and his ship Empire Elaine in Operation Dragoon, the south of France landings on 15 August 1944. In this blog I’m going to wrap up my account of his involvement in the Mediterranean during the Second World War with a similar look at Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily on 10 July 1943. As with Operation Dragoon, British merchant and Royal Navy personnel who participated in Operation Husky qualified for the Italy Star, providing that by the end of the war they had also earned the 1939-45 Star by six months operational service.

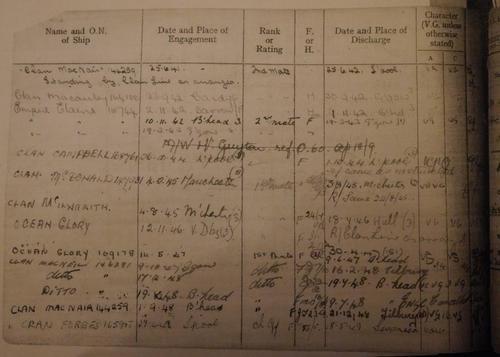

My knowledge of my grandfather’s involvement in these operations comes from conversations I had with him about his wartime service before his death in 1986 and from his personal distance log, showing the ports of call of his voyages over his nearly forty-year career as a deck officer for the Clan Line, the last eleven of them as a captain. In my last blog I reproduced the two-page spread from his log showing the single voyage he undertook in 1943-4 in Empire Elaine that encompassed both Operation Husky and Operation Dragoon, as well as her trip to the Burma front in the Bay of Bengal. I also showed the official crew list for that voyage from the ship’s records in the UK National Archives that provides proof of his presence on her as Second Officer throughout that voyage. The crew lists were the source for an abbreviated register in the National Archives known as the C.R.S. 10, which also shows his presence on Empire Elaine.

The first entries for this voyage in his personal log show the first leg being from the Clyde to Sicily, and then on to Tripoli. The relevant page of the Ship Movement Card (UK National Archives, BT 389/11/243, 389/17/50), seen below, shows the departure of Empire Elaine from the Clyde on 18 June 1943, and her next port of call as Tripoli on 15 July, five days after the Husky landings. This is what we should expect it to show, as assault locations were not ports-of-call and were top secret, with no overt indication of the participation of a ship in an operation being allowed either in the Ship Movement card or in the ship’s log book. A good clue to her purpose, though, is the note in red at the upper right, 'Allocation to S.T.A.6A for the carriage of special military cargo.' Empire Elaine was owned by the Ministry of War Transport, which appointed shipping companies, in this case the Clan Line, to manage their ships; the officers on Empire Elaine were all from the Clan Line but the crew were British merchant seamen drawn from the general 'pool', as opposed to the Lascars from India who formed the usual crew on Clan Line ships but were not employed on MOWT ships. This can be seen clearly in the crew list for the voyage (UK National Archives, BT 281/3583), showing that all of the 88 crew were British. There was a further complement of D.E.M.S. (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ship) gunners on board, drawn from the Royal Marines and the Royal Artillery. During 'Combined Operations' such as Operation Husky these 'M/T' ships, rather than commissioned ships of the Royal Navy or Royal Fleet Auxiliary, provided much of the transport for troops and equipment in assault convoys, and their crews - though still officially civilians - therefore served an entirely military role.

As with her involvement in Operation Dragoon in 1944, it would be a near-certainty that a specialised assault ship, designed to carry landing craft, sailing from the Clyde in late June 1943 – the main marshalling point and date for the Operation Husky assault convoys from the UK – and then sailing to the Mediterranean to Tripoli, would have been involved in the Sicily landings. However, as with Operation Dragoon, my intention was to discover documents – war diary entries, operational reports, and similar – that would provide primary source material for her involvement. The same caveat that I mentioned there about convoyweb.com applies here; although a remarkable body of data it is a secondary source and can only be regarded as a guide, with the primary source material from which it was derived being needed for an authoritative account.

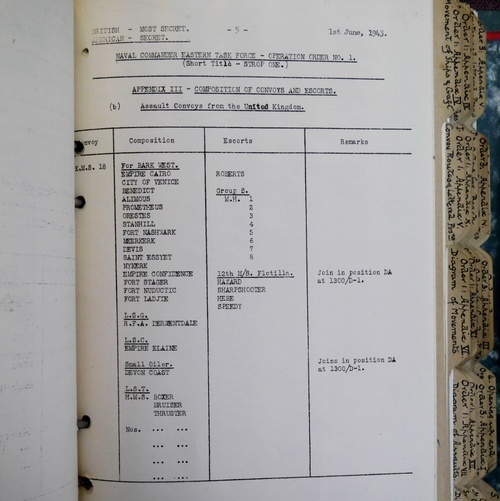

Fortunately that material is available in abundance in the declassified documents on Operation Husky available in the UK and the US National Archives, including planning documents, official diaries and first-hand accounts of the events as they unfolded, and the first retrospective reports. The following is a sample of five documents mention Empire Elaine. The first, from the Naval Commander, Eastern Task Force, Operation Order No. 1 of 1 June 1943, shows the composition of assault convoy KMS 18B, including Empire Elaine; below that is another breakdown of the convoy in the Admiralty War Diary of 18 June 1943.

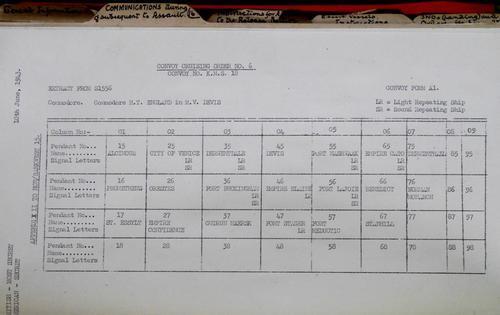

The third document, from the Force V Naval Operations Orders (UK National Archives, DEFE 2/271), shows the sailing order of the convoy, with Empire Elaine in position 46 immediately behind the convoy commodore’s flagship, Devis:

The fourth, from the Report of the Operations for the Invasion of Sicily, Commander in Chief, Mediterranean, July-August 1943, notes Empire Elaine in paragraph 20 at the bottom of the page, in a discussion of the speed in offloading landing craft achieved by Empire Elaine and the other LCS, Empire Charlian (offloading at a different sector, 'Acid'), during the landings:

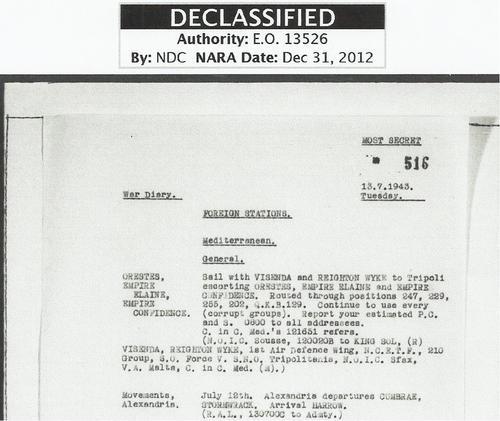

The fifth is from the Admiralty War Diary of 13 July 1943, three days after the landings, showing the presence of Empire Elaine in a group of ships from the landings taken under escort from Sicily to Tripoli:

Convoy KMS 18, later designated 18B, was part of Force V of the British Eastern Task Force, carrying troops and equipment of the First Canadian Division for landing at Bark West sector just west of the south-eastern tip of Sicily, on D-Day, 10 July 1943. Another convoy, KMF 18, made up of ships able to travel faster, left the Clyde later and was the first of the two convoys to arrive in position for the landings in the early hours of 10 July; it included several ships that had detached from the slow convoy the day before to be present off the landing zones at the earliest possible time on D-Day, though the slow convoy itself arrived soon afterwards that day. Empire Elaine carried LCMs (Landing Craft Mechanised) that were used to transport troops and equipment ashore from other ships, and given the concern that had clearly been expressed by the planners over the time needed to hoist off the LCMs it seems probable that she would have been one of the earliest arrivals.

The landings in Bark sector were only lightly opposed by Italian troops, and by far the greatest peril for the ships in those convoys was the threat of U-Boat attack in the Atlantic and Mediterranean during the passage towards Sicily. KMS 18B had proceeded without incident until it had passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and reached the north African coast just beyond Algiers, when at 2047 hours on 4 July, U-409 fired a single torpedo and struck City of Venice, which caught fire and sank at 0530 the following morning. Of the 302 Canadian troops on board and the 80 crew, a total of 22 died, almost all of them -including the ship’s Master and the Canadian commanding officer – when their lifeboat capsized and they were caught between the wreck and the rescue vessel. A little under an hour after that first attack, a second U boat, U-375, fired a spread of four torpedoes at the convoy and struck St Essylt, which also caught fire and sank a few minutes after City of Venice, at 0545 the following morning. Four lives were lost among the 401 on board, who included 302 Canadian soldiers.

U-409 was sunk seven days later north-west of Algiers, with 11 crew killed, and U-375 was sunk with all hands eighteen days after that north-west of Malta. Detailed accounts of these sinkings and the fate of the U-Boats can be found on uboat.net, a secondary source but one that could easily be verified using the type of primary documents that I cite below for the sinking in the convoy most directly concerned with Empire Elaine, on the following day, 5 July 1943.

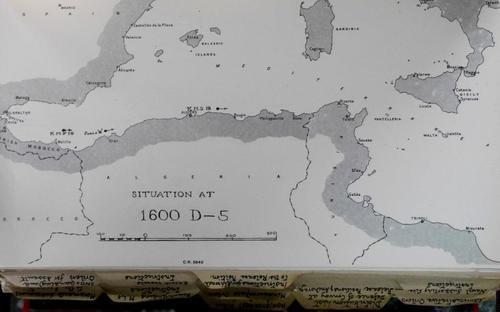

One of a series of maps in the Force V Naval Operations Orders predicting the location of convoy KMS 18 as it neared Sicily - in this case very closely predicting her position off Algiers on D-5 (5 July) when she was attacked by U-593, resulting in the loss of Devis.

One of my grandfather’s memories from Operation Husky was of having to sail through men in the water from a ship that had been torpedoed ahead of Empire Elaine in the convoy. The Force V Naval Operations Orders of 10 June 1943 for KMS 18, cited above, state that ‘No merchant ship is to leave her place in the convoy for rescue work. H.M. ships will be ordered to carry out this duty.’ (p 9, para 44). The torpedoed ship from my grandfather's account was neither St Essylt nor City of Venice, as neither were in column ahead, but instead was the third ship to be lost in KMS 18B, M.V. Devis, the ship directly ahead of Empire Elaine in her column. The orders for the convoy specify a cruising speed of 9 knots and a distance of three cables – 600 yards - between ships in columns, meaning that Empire Elaine would have had only two minutes to take evasive action before she was past the wreckage.

The Devis was the worst of the three sinkings in terms of loss of life, and is extensively covered in the primary source material (including, in the UK National Archives, ADM 199/2145, containing survivor reports, and the Canadian Military Headquarters Report No 126 of 24 November 1944, on Canadian operations in Sicily). As well as landing craft, vehicles, artillery, ammunition and other stores, Devis carried 35 British troops and 12 officers and 252 other ranks from several units of the Canadian army, commanded by Major D.S. Harkness, R.C.A. His account in the CNHQ report is the main eyewitness account:

At approx. 1545 hours, 5 July 43, the ship was struck by a torpedo just aft of amidships. The explosion was immediately beneath the OR’s mess decks, and blew the body of one man up on the bridge, and two more on the boat deck, as well as the rear end of a truck, etc. Fire broke out immediately, and within 3 to 4 minutes the fore part of the ship was cut off from the aft part. Explosions of ammunition were continuous.

After organising a rescue party to pull out men - some of them severely burned - from the mess deck, and after all personnel aft were overboard, Major Harkness himself left the ship, which sank some three minutes later at 1605, twenty minutes after the torpedo had struck. Another army officer, Captain W.G. Wells of the Royal 22e Regiment, organised similar rescue work in the fore part of the ship. Another eyewitness report from a soldier in the water described feeling the percussive effects of depth-charging as the escorts attempted to locate the U-Boat responsible. German records show this to have been U-593, which had fired two spreads of two torpedoes each at the convoy; she escaped that day but was to be sunk by allied destroyers two months later, her entire crew surviving and being taken into captivity.

Several hours after the torpedoing all of the survivors from Devis had been picked up by the convoy escorts and were taken by a destroyer to Bougie, Tunisia, where those who were uninjured were partially re-equipped and sent on to Sicily, rejoining the Canadian assault force on D+3 (13 July) - by which time the division had progressed inland from its landing point near the south-east tip of Sicily. For their part in the rescue Major Harkness received the George Medal and Captain Wells an MBE, and the ship’s Master and Chief Officer the OBE and MBE respectively (ADM 99/142). The 51 Canadian soldiers who died on Devis and those from St Essylt and City of Venice were the first of almost 6,000 Canadian troops to be killed in the Italian campaign over the following 19 months, before the 1st Canadian Division was withdrawn in February 1945 and redeployed to north-west Europe.

Early morning view on 10 July of one of the assault convoys approaching Sicily, showing the tail-end of the rough seas which had hampered progress during the previous day (Admiralty Official Collection, Imperial War Museum A 18096).

My grandfather’s main memory of the Operation Husky landings themselves was being anchored directly inshore from a Royal Navy monitor that fired its shells over Empire Elaine, with huge percussive effect. Monitors were specialised warships with shallow drafts and wide beams, designed to operate close inshore to provide fire support inland, their single twin-barrelled 15 inch gun turret being mounted on a high barbette to give a maximum range of over twenty miles.

Two accounts survive by other officers in the same sector as Empire Elaine - Bark West - that closely parallel my grandfather’s, and both refer to the only monitor in that sector, HMS Roberts. 69-year old Captain David Bone of the liner Circassia (later Captain Sir David Bone, CBE) described being taken by surprise by the muzzle blast as it lashed his clothing and pounding his ears, which he had failed to protect with ear plugs (Bone, David W. Merchantman Re-armed. London, Chatto and Windus, 1949). Another account comes from the famous Canadian author Farley Mowat, then a young infantry officer in the same assault: ‘Four incandescent spheres burst from her suddenly-revealed grey bulk – four suns … that seemed to ignite the whole arc of the southern horizon in flickering red and yellow lightning … It took perhaps three seconds for the sound to hit us and then we were cowering behind the gunwales, hands over ears, as cataclysmic thunder overwhelmed our world’ (And no Birds Sang, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart, 1979: 74). The fire report for HMS Roberts, contained in the Naval Force East ships’ bombardment reports for that sector (DEFE 2/271 in the UK National Archives), shows that she first opened fire from her anchorage point at 0510 hours with ten rounds against an Italian shore battery, firing four rounds again at the same battery at 0540 hours and silencing it. A second monitor, HMS Erebus, operated further up the coast in ‘Acid’ sector some ten miles south of Syracuse. One of the 15 inch guns from Roberts that fired over my grandfather that day survives and is mounted outside the Imperial War Museum in London.

This photograph on the morning of the assault was taken by Lt H.A. Mason, R.N., an official Navy photographer, and shows an LCM (Landing Craft Mechanised), Mark 3. This is the first of a sequence of photos that Mason took beginning on HMS Hilary, the Force V HQ ship, and ending with him on shore. It was taken off 'Bark West' where the only LCM carrier was Empire Elaine, so this LCM had very probably been hoisted off her shortly before the picture was taken (Admiralty Official Collection, Imperial War Museum A 17955).

Having offloaded her LCMs, Empire Elaine then sailed away under escort towards Tripoli in Libya, where she joined a convoy to Port Said and eventually reached the Bay of Bengal in early 1944, carrying landing craft to Chittagong near the Burmese border for the war against Japan. A little over a year after Operation Husky she was back in Sicily at Augusta, the port just north of Syracuse, her staging point for another huge seaborne invasion - the Operation Dragoon landings off the south of France on 15 August 1944, described in my previous blog.

December 14, 2014

M.V. Empire Elaine and Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944

The assault ship Empire Elaine on the Cyde in 1943 during her refit in preparation for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in July of that year.

'Operation Dragoon' was the codename for the Allied landings in the south of France on 15 August 1944, a massive naval and airborne assault that served as the counterpart to the Normandy landings a little over two months earlier. The assault was primarily a US operation, with most of the troops landed around Cavalaire Bay being from three US divisions, but many of the assault and supply ships and their escorts were British. Many British merchant and Royal Navy seamen who took part in Operation Dragoon qualified for the Italy Star, a campaign medal awarded to seamen for participation in seaborne assaults in the Mediterranean from the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 to the end of the war.

One of the merchant seamen who took part in Operation Dragoon was my grandfather, Captain Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins, as Second Officer of the L.S.C. (Landing Ship Carrier) Empire Elaine, a specialised assault ship built in 1942 for the transport of landing craft. I wrote a few blogs back about the twenty month voyage she undertook from 1943-44 that encompassed not only Operation Dragoon but also Operation Husky (the Sicily landings in 1943) and the supply of landing craft for the Burma campaign in the Bay of Bengal. This blog is a more detailed presentation of the primary source material that traces my grandfather and Empire Elaine's involvement in Operation Dragoon. I've researched this over the years since talking about it at length to my grandfather before his death in 1986, and I thought a summary of the type of evidence available might be useful for anyone else intent on discovering records of a merchant seaman's involvement in this operation.

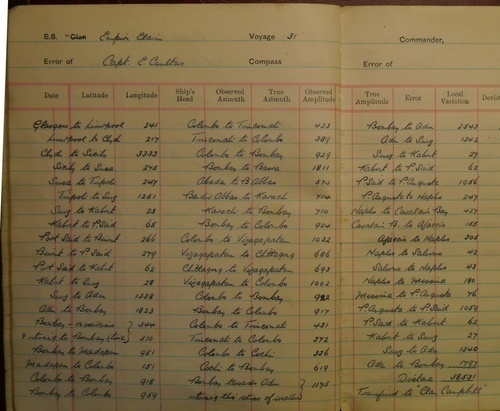

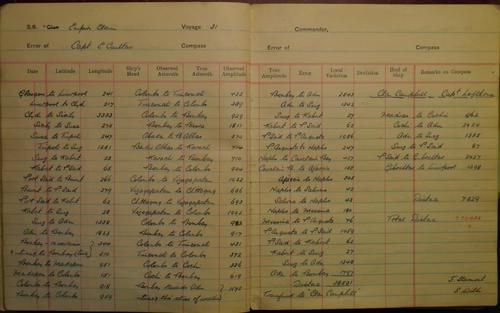

My first port of call was my grandfather's personal logbook. On the page opposite you can see all of his voyages through the war, including two, numbers 30 and 31, as Second Officer of Empire Elaine, from 27 October 1942 until his transfer to Clan Campbell on 25 October 1944. On the page below you can see the full details of ports and distances for the second of those voyages, number 31, beginning at Glasgow on the Clyde - on 24 June 1943 - and ending in Bombay with his transfer to Clan Campbell. In the third column you can see all of the ship's movements associated with Operation Dragoon, from Port Said in Egypt to Augusta in Sicily, from August to Naples, from Naples to Cavalaire Bay and then from there to Ajaccio in Corsica and back to Naples, before the ship returned south and east across the Mediterranean to Port Said.

My next step was to go to the UK National Archives at Kew to find his 'C.R.S. 10' record and the Ship Movement Cards for Empire Elaine, and to see whether there were any surviving official log books and crew lists for the ship. The C.R.S. 10 record (see here) - the letters stand for 'Central Registry of Seamen' - was established in 1941 to record an outline of merchant seamen's employment during the war, and was extracted from the ships' official log books and crew lists. The Ship Movement Cards, now digitised and downloadable here for a fee from the National Archives, were instituted at the outbreak of war to provide a basic record of ship movements at a time when ship's masters were prohibited from keeping their normal peacetime distance logs, for reasons of national security. The cards often don't include all of a ship's ports of call in a voyage and in the case of ships involved in assault convoys they don't include the destination, as that was top secret - so I knew that the Ship Movement Cards would contain less detail related to Operation Dragoon than my grandfather's personal log.

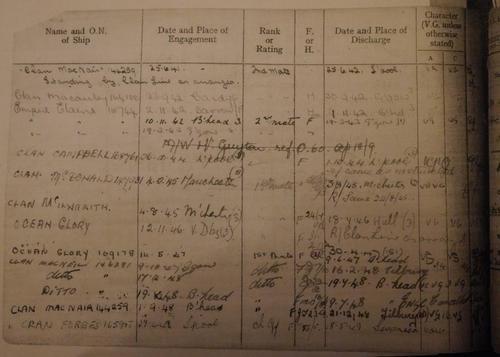

The image opposite is his C.R.S. 10 record covering the war years from the institution of the record in 1941. It shows that he joined Empire Elaine first on 9 November 1942 for a nine-day voyage to Birkenhead, where he immediately re-engaged for her first overseas voyage - his voyage 30 - returning to Glasgow on 19 March 1943. It then shows that he immediately re-engaged again and remained with her until transferring to Clan Campbell on 26 October 1944. His presence on Empire Elaine on that long voyage, including Operation Dragoon, is further shown in the Official Log-Book and List of Crew, the basis for the C.R.S. 10 record. Only a portion of these primary records for merchant ships in the Second World War have survived, but by good fortune the National Archives includes the complete log-books and crew lists for all of Empire Elaine's wartime voyages (in BT 381/2607 and 381/3583, searchable by a ship's official number, in this case 167744). In the excerpt below from the crew list showing the Captain and deck officers you can see my grandfather's name, third down, as Second Mate, along with his date of engagement, 19 March 1943, and the date of his departure from Empire Elaine in Bombay along with the other deck officers, 19 October 1944, a week before they joined Clan Campbell in Madras - after a train journey across India - for the voyage home:

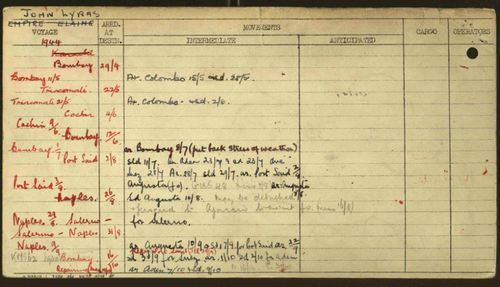

The fourth image, below, is the Ship Movement Card for Empire Elaine from 1944 covering the dates of her involvement in Operation Dragoon (her name is altered on the card to John Lyras, her new name after being sold in 1947). You can see a sequence of ports that matches my grandfather's log: departure from Port Said on 3 August, and then arrival at Augusta in Sicily on 8 August, at Ajaccio in Corsica on 16 August, at Naples on 28 August, and at Naples again on 29 August. What is missing - and what should never be on a Ship Movement Card - is any detail of her voyage between 8 and 16 August, when I know from my grandfather's log that she sailed to Cavalaire Bay as part of Operation Dragoon. Even without his log it would be a near certainty that a specialised assault ship, designed for carrying landing craft, arriving the day after the invasion at Ajaccio - a staging port for ships returning from the invasion zone - would have been part of the Operation Dragoon assault convoys.

The website convoyweb, based largely on the research of Lt-Cdr Arnold Hague, RNR, contains a huge database of ships and convoys during the war, including a searchable ship index that shows Empire Elaine to have been part of assault convoy SM 1C from Naples to Operation Dragoon. However, it is a secondary source with no citation of primary documentation and can therefore only only be used as a guide. I was intent on discovering primary sources - official war diaries and operation reports, in particular - that would provide authoritative documentation of Empire Elaine's involvement in that convoy, and if possible provide more detail to flesh out her activities on those days.

The best documentation has come from recently declassified material from the US National Archives related to Operation Dragoon. A large number of these declassified Second World War documents can now be seen online at fold3. The four documents reproduced below provide precisely the primary documentation that I was after. The first is in the Report of the Naval Commander, Western Task Force, Commander 8th Fleet, entitled The Invasion of Southern France, filed on 15 November 1944 (File A 16-3, Serial 01568). It details the composition of Alpha Attack Force, listing Empire Elaine (the only LSC):

The second is from the Report of Amphibious Operations conducted against the enemy by units of Alpha Red Assault Group, in southern France, during the period 9 August 1944 - 25 August 1944, filed on 1 October 1944. The page contains the report from 21 August of USS LST 265, and includes a complete list of the vessels in Convoy SM 1B, including Empire Elaine (referred to by the Americans as 'HMS'), their arrival time at the landing zone and their mission:

The third from the War Diary of USS SC-695, describing her duty from 12-15 August escorting the convoy from Naples to Cavalaire Bay to the final assault hour, listing Empire Elaine:

The fourth, from the Report of Operations, Task Group 80.6, of 17 August 1944, includes Empire Elaine in the list of ships comprising Convoy CRM-3 escorted from the landing zone to Ajaccio in Corsica following the landings:

Red Beach, Cavalaire Bay, Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944. A view taken from a British-manned landing craft.

These documents corroborate everything in my grandfather's log and allow the partial picture in the Ship Movement Card to be fully understood. Following her departure from Augusta in Sicily on 8 August 1944, Empire Elaine sailed to Naples and there joined Convoy SM 1B, part of 'Alpha Attack Force' under Rear Admiral Lowry, USN. The convoy included numerous L.S.T.s as well as other British and American assault and supply ships, with Empire Elaine being the only LSC. The convoy arrived in the assault area at 0400 on 15 August, with the final assault phase underway by 0455. The assault sector for this convoy was Cavalaire Bay, including 'Red Beach'. After offloading her landing craft, Empire Elaine joined convoy CRM-3 to Ajaccio in Corsica, having successfully completed her second assault landing in the Mediterranean theatre, her first having been Operation Husky off Sicily thirteen months earlier. Operation Dragoon was not, however, to be her last - almost seven months later and several thousand miles away she was delivering landing craft at Chittagong close the Burmese border for use in further assaults, along the Arakan coast against the Japanese.

See my next blog for an account of Empire Elaine and Operation Husky.

Red Beach sector, Cavalaire Bay, Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944. Another view from the same sequence as the previous image showing British-manned landing craft making their way to shore. These are LCMs (Landing Craft Mechanized), and since Empire Elaine was the only specialised LCM carrier in Convoy SM 1C these could well have been among the LCMs that she transported to the landings.

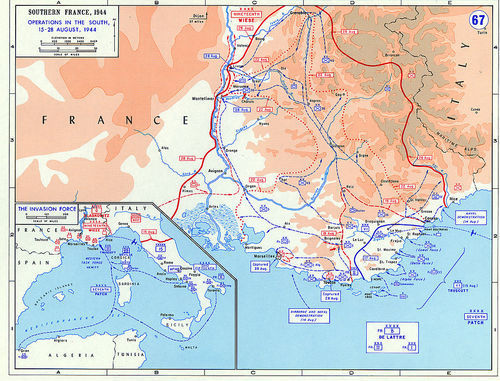

Empire Elaine was part of 'Alpha Force', off Cavalaire and St Tropez. Red Beach was in the south-west part of this sector within Cavalaire Bay towards Cap Negre.

Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944, and Convoy SM 1C

The assault ship Empire Elaine on the Cyde in 1943 during her refit in preparation for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily in July of that year.

'Operation Dragoon' was the codename for the Allied landings in the south of France on 15 August 1944, a massive naval and airborne assault that served as the counterpart to the Normandy landings a little over two months earlier. The assault was primarily a US operation, with most of the troops landed around Cavalaire Bay being from three US divisions, but many of the assault and supply ships and their escorts were British. The thousands of British merchant and Royal Navy seamen who took part in Operation Dragoon qualified for the Italy Star, a campaign medal awarded to seamen for participation in seaborne assaults in the Mediterranean from the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 to the end of the war.

One of the merchant seamen who took part in Operation Dragoon was my grandfather, Captain Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins, as Second Officer of the L.S.C. (Landing Ship Carrier) Empire Elaine, a specialised assault ship built in 1942 for the transport of landing craft. I wrote a few blogs back about the twenty month voyage she undertook from 1943-44 that encompassed not only Operation Dragoon but also Operation Husky (the Sicily landings in 1943) and the supply of landing craft for the Burma campaign in the Bay of Bengal. This blog is a more detailed presentation of the primary source material that traces my grandfather and Empire Elaine's involvement in Operation Dragoon. I've researched this over the years since talking about it at length to my grandfather before his death in 1986, and I thought it might be useful for anyone else intent on discovering records of a merchant seaman's involvement in this operation.

My first port of call was my grandfather's personal logbook. On the page opposite you can see all of his voyages through the war, including two, numbers 30 and 31, as Second Officer of Empire Elaine, from 27 October 1942 until his transfer to Clan Campbell on 25 October 1944. On the page below you can see the full details of ports and distances for the second of those voyages, number 31, beginning at Glasgow on the Clyde - on 24 June 1943 - and ending in Bombay with his transfer to Clan Campbell. In the third column you can see all of the ship's movements associated with Operation Dragoon, from Port Said in Egypt to Augusta in Sicily, from August to Naples, from Naples to Cavalaire Bay and then from there to Ajaccio in Corsica and back to Naples, before the ship returned south and east across the Mediterranean to Port Said.

My next step was to go to the UK National Archives at Kew to find his 'C.R.S. 10' record and the Ship Movement Cards for Empire Elaine. The C.R.S. 10 record - the letters stand for 'Central Registry of Seamen' - was established in 1941 to record details of merchant seamen's employment during the war. The Ship Movement Cards, now digitised and downloadable from the National Archives, were instituted at the outbreak of war to provide a basic record of ship movements at a time when ship's masters were prohibited from keeping their normal peacetime records and ship's logs, for reasons of national security. The cards often don't include all of a ship's ports of call in a voyage and in the case of ships involved in assault convoys they don't include the destination, as that was top secret - so I knew that the Ship Movement Cards would contain less detail related to Operation Dragoon than my grandfather included in his personal log.

The image opposite is his C.R.S. 10 record covering the war years from the institution of the record in 1941. It shows that he joined Empire Elaine first on 9 November 1942 for a nine-day voyage to Birkenhead, where he immediately re-engaged for her first overseas voyage - his voyage 30 - returning to Glasgow on 19 March 1943. It then shows that he immediately re-engaged and remained with her until transferring to Clan Campbell on 26 October 1944 (the place of engagement with Clan Campbell is stated as Liverpool for administrative purposes, as the engagement of all officers in his shipping line who transferred to another ship overseas was officially registered in one of their UK home ports; as his log shows, he joined Clan Campbell from Empire Elaine in Madras, the presence of Clan Campbell in Madras on 26 October 1944 being shown on her Ship Movement Card).

The second image is the Ship Movement Card for Empire Elaine from 1944 covering her involvement in Operation Dragoon (her name is altered on the card to John Lyras, her new name after being sold in 1947). You can see a sequence of ports that matches my grandfather's log: departure from Port Said on 3 August, and then arrival at Augusta in Sicily on 8 August, at Ajaccio in Corsica on 16 August, at Naples on 28 August, and at Naples again on 29 August. What is missing - and what should never be on a Ship Movement Card - is any detail of her voyage between 8 and 16 August, when I know from my grandfather's log that she sailed to Cavalaire Bay and was part of Operation Dragoon. Even without his log it would be a near certainty that a specialised assault ship, designed for carrying landing craft, arriving the day after the invasion at Ajaccio - a staging port for ships returning from the invasion zone - would have been part of the Operation Dragoon assault convoys.

The website convoyweb, based largely on the research of Lt-Cdr Arnold Hague, RNR, contains a huge database of ships and convoys during the war, including a searchable ship index that shows Empire Elaine to have been part of assault convoy SM 1C from Naples to Operation Dragoon. My research has only ever confirmed the reliability of that database, including the research set out here. However, it is a secondary source with no citation of primary sources and can therefore only only be used as a guide. I was intent on discovering primary sources - official war diaries and operation reports, in particular - that would provide authoritative documentation of Empire Elaine's involvement in that convoy, and if possible provide more detail to flesh out her activities on those days.

My breakthrough came with the discovery of recently declassified material from the US National Archives related to Operation Dragoon. A large number of these declassified Second World War documents can now be seen online at fold3. The four documents reproduced below provide precisely the primary documentation that I was after. The first is in the Report of the Naval Commander, Western Task Force, Commander 8th Fleet, entitled The Invasion of Southern France, filed on 15 November 1944 (File A 16-3, Serial 01568). It details the composition of Alpha Attack Force, listing Empire Elaine:

The second is from the Report of Amphibious Operations conducted against the enemy by units of Alpha Red Assault Group, in southern France, during the period 9 August 1944 - 25 August 1944, filed on 1 October 1944. The page contains the report from 21 August of USS LST 265, and includes a complete list of the vessels in Convoy SM 1B, including Empire Elaine, their arrival time at the landing zone and their mission:

The third from the War Diary of USS SC-695, describing her duty from 12-15 August escorting the convoy from Naples to Cavalaire Bay to the final assault hour, listing Empire Elaine:

The fourth, from the Report of Operations, Task Group 80.6, of 17 August 1944, includes Empire Elaine in the list of ships comprising Convoy CRM-3 escorted from the landing zone to Ajaccio in Corsica following the landings:

Red Beach, Cavalaire Bay, Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944. A view taken from a British-manned landing craft.

These documents corroborate everything in my grandfather's log and allow the partial picture in the Ship Movement Card to be fully understood. Following her departure from Augusta in Sicily on 8 August 1944, Empire Elaine sailed to Naples and there joined Convoy SM 1B, part of 'Alpha Attack Force' under Rear Admiral Lowry, USN. The convoy included numerous L.S.T.s as well as other British and American assault and supply ships, with Empire Elaine being the only LSC. The convoy arrived in the assault area at 0400 on 15 August, with the final assault phase underway by 0455. The assault sector for this convoy was Cavalaire Bay, including 'Red Beach'. After offloading her landing craft, Empire Elaine joined convoy CRM-3 to Ajaccio in Corsica, having successfully completed her second assault landing in the Mediterranean theatre, her first having been Operation Husky off Sicily thirteen months earlier. Operation Dragoon was not, however, to be her last - almost seven months later and several thousand miles away she was delivering landing craft at Chittagong close the Burmese border for use in further assaults, along the Arakan coast against the Japanese.

Red Beach sector, Cavalaire Bay, Operation Dragoon, 15 August 1944. Another view from the same sequence as the previous image showing British-manned landing craft making their way to shore. These are LCMs (Landing Craft Mechanized), and since Empire Elaine was the only specialised LCM carrier in Convoy SM 1C these could well have been among the LCMs that she transported to the landings.

Empire Elaine was part of 'Alpha Force', off Cavalaire and St Tropez. Red Beach was in the south-west part of this sector within Cavalaire Bay towards Cap Negre.