M.V. Empire Elaine, convoy KMS 18B and Operation Husky, 10 July 1943

Assault ship Empire Elaine on the Clyde in early 1943, being refitted and repainted in preparation for Operation Husky.

In my last blog I presented a range of primary documentation for the involvement of my grandfather Captain L.W. Gibbins and his ship Empire Elaine in Operation Dragoon, the south of France landings on 15 August 1944. In this blog I’m going to wrap up my account of his involvement in the Mediterranean during the Second World War with a similar look at Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily on 10 July 1943. As with Operation Dragoon, British merchant and Royal Navy personnel who participated in Operation Husky qualified for the Italy Star, providing that by the end of the war they had also earned the 1939-45 Star by six months operational service.

My knowledge of my grandfather’s involvement in these operations comes from conversations I had with him about his wartime service before his death in 1986 and from his personal distance log, showing the ports of call of his voyages over his nearly forty-year career as a deck officer for the Clan Line, the last eleven of them as a captain. In my last blog I reproduced the two-page spread from his log showing the single voyage he undertook in 1943-4 in Empire Elaine that encompassed both Operation Husky and Operation Dragoon, as well as her trip to the Burma front in the Bay of Bengal. I also showed the official crew list for that voyage from the ship’s records in the UK National Archives that provides proof of his presence on her as Second Officer throughout that voyage. The crew lists were the source for an abbreviated register in the National Archives known as the C.R.S. 10, which also shows his presence on Empire Elaine.

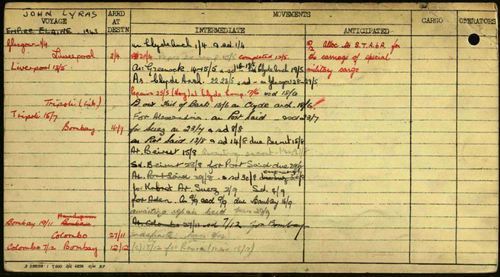

The first entries for this voyage in his personal log show the first leg being from the Clyde to Sicily, and then on to Tripoli. The relevant page of the Ship Movement Card (UK National Archives, BT 389/11/243, 389/17/50), seen below, shows the departure of Empire Elaine from the Clyde on 18 June 1943, and her next port of call as Tripoli on 15 July, five days after the Husky landings. This is what we should expect it to show, as assault locations were not ports-of-call and were top secret, with no overt indication of the participation of a ship in an operation being allowed either in the Ship Movement card or in the ship’s log book. A good clue to her purpose, though, is the note in red at the upper right, 'Allocation to S.T.A.6A for the carriage of special military cargo.' Empire Elaine was owned by the Ministry of War Transport, which appointed shipping companies, in this case the Clan Line, to manage their ships; the officers on Empire Elaine were all from the Clan Line but the crew were British merchant seamen drawn from the general 'pool', as opposed to the Lascars from India who formed the usual crew on Clan Line ships but were not employed on MOWT ships. This can be seen clearly in the crew list for the voyage (UK National Archives, BT 281/3583), showing that all of the 88 crew were British. There was a further complement of D.E.M.S. (Defensively Equipped Merchant Ship) gunners on board, drawn from the Royal Marines and the Royal Artillery. During 'Combined Operations' such as Operation Husky these 'M/T' ships, rather than commissioned ships of the Royal Navy or Royal Fleet Auxiliary, provided much of the transport for troops and equipment in assault convoys, and their crews - though still officially civilians - therefore served an entirely military role.

As with her involvement in Operation Dragoon in 1944, it would be a near-certainty that a specialised assault ship, designed to carry landing craft, sailing from the Clyde in late June 1943 – the main marshalling point and date for the Operation Husky assault convoys from the UK – and then sailing to the Mediterranean to Tripoli, would have been involved in the Sicily landings. However, as with Operation Dragoon, my intention was to discover documents – war diary entries, operational reports, and similar – that would provide primary source material for her involvement. The same caveat that I mentioned there about convoyweb.com applies here; although a remarkable body of data it is a secondary source and can only be regarded as a guide, with the primary source material from which it was derived being needed for an authoritative account.

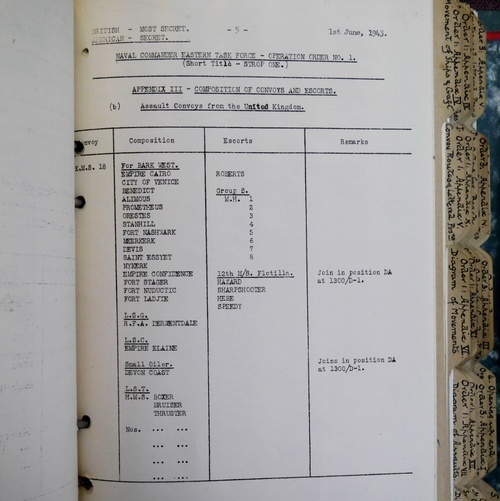

Fortunately that material is available in abundance in the declassified documents on Operation Husky available in the UK and the US National Archives, including planning documents, official diaries and first-hand accounts of the events as they unfolded, and the first retrospective reports. The following is a sample of five documents mention Empire Elaine. The first, from the Naval Commander, Eastern Task Force, Operation Order No. 1 of 1 June 1943, shows the composition of assault convoy KMS 18B, including Empire Elaine; below that is another breakdown of the convoy in the Admiralty War Diary of 18 June 1943.

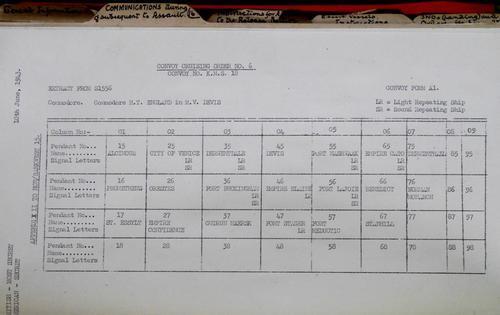

The third document, from the Force V Naval Operations Orders (UK National Archives, DEFE 2/271), shows the sailing order of the convoy, with Empire Elaine in position 46 immediately behind the convoy commodore’s flagship, Devis:

The fourth, from the Report of the Operations for the Invasion of Sicily, Commander in Chief, Mediterranean, July-August 1943, notes Empire Elaine in paragraph 20 at the bottom of the page, in a discussion of the speed in offloading landing craft achieved by Empire Elaine and the other LCS, Empire Charlian (offloading at a different sector, 'Acid'), during the landings:

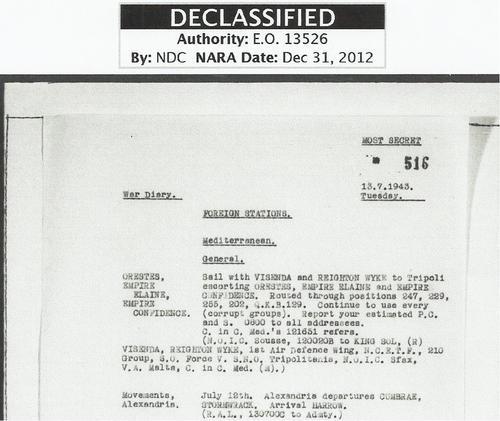

The fifth is from the Admiralty War Diary of 13 July 1943, three days after the landings, showing the presence of Empire Elaine in a group of ships from the landings taken under escort from Sicily to Tripoli:

Convoy KMS 18, later designated 18B, was part of Force V of the British Eastern Task Force, carrying troops and equipment of the First Canadian Division for landing at Bark West sector just west of the south-eastern tip of Sicily, on D-Day, 10 July 1943. Another convoy, KMF 18, made up of ships able to travel faster, left the Clyde later and was the first of the two convoys to arrive in position for the landings in the early hours of 10 July; it included several ships that had detached from the slow convoy the day before to be present off the landing zones at the earliest possible time on D-Day, though the slow convoy itself arrived soon afterwards that day. Empire Elaine carried LCMs (Landing Craft Mechanised) that were used to transport troops and equipment ashore from other ships, and given the concern that had clearly been expressed by the planners over the time needed to hoist off the LCMs it seems probable that she would have been one of the earliest arrivals.

The landings in Bark sector were only lightly opposed by Italian troops, and by far the greatest peril for the ships in those convoys was the threat of U-Boat attack in the Atlantic and Mediterranean during the passage towards Sicily. KMS 18B had proceeded without incident until it had passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and reached the north African coast just beyond Algiers, when at 2047 hours on 4 July, U-409 fired a single torpedo and struck City of Venice, which caught fire and sank at 0530 the following morning. Of the 302 Canadian troops on board and the 80 crew, a total of 22 died, almost all of them -including the ship’s Master and the Canadian commanding officer – when their lifeboat capsized and they were caught between the wreck and the rescue vessel. A little under an hour after that first attack, a second U boat, U-375, fired a spread of four torpedoes at the convoy and struck St Essylt, which also caught fire and sank a few minutes after City of Venice, at 0545 the following morning. Four lives were lost among the 401 on board, who included 302 Canadian soldiers.

U-409 was sunk seven days later north-west of Algiers, with 11 crew killed, and U-375 was sunk with all hands eighteen days after that north-west of Malta. Detailed accounts of these sinkings and the fate of the U-Boats can be found on uboat.net, a secondary source but one that could easily be verified using the type of primary documents that I cite below for the sinking in the convoy most directly concerned with Empire Elaine, on the following day, 5 July 1943.

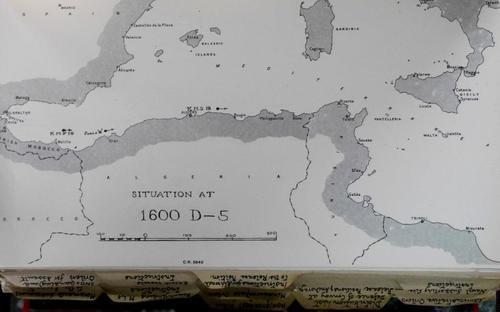

One of a series of maps in the Force V Naval Operations Orders predicting the location of convoy KMS 18 as it neared Sicily - in this case very closely predicting her position off Algiers on D-5 (5 July) when she was attacked by U-593, resulting in the loss of Devis.

One of my grandfather’s memories from Operation Husky was of having to sail through men in the water from a ship that had been torpedoed ahead of Empire Elaine in the convoy. The Force V Naval Operations Orders of 10 June 1943 for KMS 18, cited above, state that ‘No merchant ship is to leave her place in the convoy for rescue work. H.M. ships will be ordered to carry out this duty.’ (p 9, para 44). The torpedoed ship from my grandfather's account was neither St Essylt nor City of Venice, as neither were in column ahead, but instead was the third ship to be lost in KMS 18B, M.V. Devis, the ship directly ahead of Empire Elaine in her column. The orders for the convoy specify a cruising speed of 9 knots and a distance of three cables – 600 yards - between ships in columns, meaning that Empire Elaine would have had only two minutes to take evasive action before she was past the wreckage.

The Devis was the worst of the three sinkings in terms of loss of life, and is extensively covered in the primary source material (including, in the UK National Archives, ADM 199/2145, containing survivor reports, and the Canadian Military Headquarters Report No 126 of 24 November 1944, on Canadian operations in Sicily). As well as landing craft, vehicles, artillery, ammunition and other stores, Devis carried 35 British troops and 12 officers and 252 other ranks from several units of the Canadian army, commanded by Major D.S. Harkness, R.C.A. His account in the CNHQ report is the main eyewitness account:

At approx. 1545 hours, 5 July 43, the ship was struck by a torpedo just aft of amidships. The explosion was immediately beneath the OR’s mess decks, and blew the body of one man up on the bridge, and two more on the boat deck, as well as the rear end of a truck, etc. Fire broke out immediately, and within 3 to 4 minutes the fore part of the ship was cut off from the aft part. Explosions of ammunition were continuous.

After organising a rescue party to pull out men - some of them severely burned - from the mess deck, and after all personnel aft were overboard, Major Harkness himself left the ship, which sank some three minutes later at 1605, twenty minutes after the torpedo had struck. Another army officer, Captain W.G. Wells of the Royal 22e Regiment, organised similar rescue work in the fore part of the ship. Another eyewitness report from a soldier in the water described feeling the percussive effects of depth-charging as the escorts attempted to locate the U-Boat responsible. German records show this to have been U-593, which had fired two spreads of two torpedoes each at the convoy; she escaped that day but was to be sunk by allied destroyers two months later, her entire crew surviving and being taken into captivity.

Several hours after the torpedoing all of the survivors from Devis had been picked up by the convoy escorts and were taken by a destroyer to Bougie, Tunisia, where those who were uninjured were partially re-equipped and sent on to Sicily, rejoining the Canadian assault force on D+3 (13 July) - by which time the division had progressed inland from its landing point near the south-east tip of Sicily. For their part in the rescue Major Harkness received the George Medal and Captain Wells an MBE, and the ship’s Master and Chief Officer the OBE and MBE respectively (ADM 99/142). The 51 Canadian soldiers who died on Devis and those from St Essylt and City of Venice were the first of almost 6,000 Canadian troops to be killed in the Italian campaign over the following 19 months, before the 1st Canadian Division was withdrawn in February 1945 and redeployed to north-west Europe.

Early morning view on 10 July of one of the assault convoys approaching Sicily, showing the tail-end of the rough seas which had hampered progress during the previous day (Admiralty Official Collection, Imperial War Museum A 18096).

My grandfather’s main memory of the Operation Husky landings themselves was being anchored directly inshore from a Royal Navy monitor that fired its shells over Empire Elaine, with huge percussive effect. Monitors were specialised warships with shallow drafts and wide beams, designed to operate close inshore to provide fire support inland, their single twin-barrelled 15 inch gun turret being mounted on a high barbette to give a maximum range of over twenty miles.

Two accounts survive by other officers in the same sector as Empire Elaine - Bark West - that closely parallel my grandfather’s, and both refer to the only monitor in that sector, HMS Roberts. 69-year old Captain David Bone of the liner Circassia (later Captain Sir David Bone, CBE) described being taken by surprise by the muzzle blast as it lashed his clothing and pounding his ears, which he had failed to protect with ear plugs (Bone, David W. Merchantman Re-armed. London, Chatto and Windus, 1949). Another account comes from the famous Canadian author Farley Mowat, then a young infantry officer in the same assault: ‘Four incandescent spheres burst from her suddenly-revealed grey bulk – four suns … that seemed to ignite the whole arc of the southern horizon in flickering red and yellow lightning … It took perhaps three seconds for the sound to hit us and then we were cowering behind the gunwales, hands over ears, as cataclysmic thunder overwhelmed our world’ (And no Birds Sang, Toronto, McClelland and Stewart, 1979: 74). The fire report for HMS Roberts, contained in the Naval Force East ships’ bombardment reports for that sector (DEFE 2/271 in the UK National Archives), shows that she first opened fire from her anchorage point at 0510 hours with ten rounds against an Italian shore battery, firing four rounds again at the same battery at 0540 hours and silencing it. A second monitor, HMS Erebus, operated further up the coast in ‘Acid’ sector some ten miles south of Syracuse. One of the 15 inch guns from Roberts that fired over my grandfather that day survives and is mounted outside the Imperial War Museum in London.

This photograph on the morning of the assault was taken by Lt H.A. Mason, R.N., an official Navy photographer, and shows an LCM (Landing Craft Mechanised), Mark 3. This is the first of a sequence of photos that Mason took beginning on HMS Hilary, the Force V HQ ship, and ending with him on shore. It was taken off 'Bark West' where the only LCM carrier was Empire Elaine, so this LCM had very probably been hoisted off her shortly before the picture was taken (Admiralty Official Collection, Imperial War Museum A 17955).

Having offloaded her LCMs, Empire Elaine then sailed away under escort towards Tripoli in Libya, where she joined a convoy to Port Said and eventually reached the Bay of Bengal in early 1944, carrying landing craft to Chittagong near the Burmese border for the war against Japan. A little over a year after Operation Husky she was back in Sicily at Augusta, the port just north of Syracuse, her staging point for another huge seaborne invasion - the Operation Dragoon landings off the south of France on 15 August 1944, described in my previous blog.