David Gibbins's Blog, page 11

September 25, 2013

THE LAST GOSPEL: shipwreck evidence for literacy in the ancient world

Our boats over the Plemmirio Roman wreck, looking south along the shore of eastern Sicily towards Africa.

I’ve just

finished reading Bryan Ward-Perkins’ excellent The Fall of Rome (Oxford University Press, 2006) in which he uses

archaeological evidence to argue – very persuasively, in my view – that the end

of the western Roman empire in the 5th century AD was not a period

of ‘transition’ but rather one of devastation and economic collapse, in terms

that Edward Gibbon would have understood almost three centuries ago when he

wrote The Decline and Fall of the Roman

Empire. Gibbon, of course, had no archaeological data at his disposal, but

the number of excavations and syntheses now published has allowed historians

such as Ward-Perkins to use the evidence with confidence, seeing patterns for

example in pottery distribution that can be related to wider questions about

the ancient economy as a whole. The fact that many ancient

historians have now worked on archaeological sites means that they have a

clearer grasp of the possibilities and limitations of the evidence than their

predecessors, something that has helped to merge the disciplines and allow a

unitary approach to the big questions of ancient history – questions that are

still there to be tackled, as Ward-Perkins demonstrates with great verve in his

book.

A photo of me with other expedition divers more than 50 metres deep below the Roman wreck at Plemmirio, with a heavily encrusted Byzantine amphora. Divers will spot my beloved Poseidon regulator - bought with the proceeds of a summer working on a farm when I was 16, and still used by me today (you can see it in the ice-dive and night-dive videos on the website homepage).

One of the

more fascinating contributions of archaeology to this debate has been to reveal

the extent of literacy in the Roman world, and its apparent decline following

the Germanic invasions of the 5th century AD. Ward-Perkins cites the best-known evidence

that literacy at the height of empire, at least at a basic level, was not just the

preserve of the aristocracy: the

graffiti found on the walls of Pompeii, including the famous brothel

inscriptions (‘Sabinus hic,’ ‘Sabinus was here’); the soldiers’ letters found

in the waterlogged site of Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall; and the thousands of

scraps of papyrus preserved in the Faiyum and elsewhere in Egypt. Most

obviously related to his thesis – because they too disappear almost entirely in

the west after the 5th century – are inscriptions concerned with the

production and distribution of goods, especially inscribed potsherds at kiln

sites and stamped and painted inscriptions on amphorae, the storage vessels

produced in their millions to transport wine, olive oil, fish-sauce and other

products around the Roman world during its economic heyday.

Africano Grande amphoras from the wreck, including the neck stamped PP at upper left (drawing: David Gibbins).

Jenny Lobell with an Africano Grande amphora from the wreck.

I’d like to add

a small but poignant example in support of this thesis from a Roman shipwreck

excavated under my direction off Sicily. Wreck finds can be particularly

meaningful because they usually represent accidental loss of material in use

rather than rubbish, and this can give extra significance to any inscriptions found.

The Plemmirio ship, dating from about AD 200, carried a small cargo of cylindrical

‘Africano grande’ and ‘Africano piccolo’ amphorae, the former probably filled

with fish sauce and the latter olive oil. She was wrecked at a time when Rome’s

main source of olive oil – part of the emperors’ handout to the people – was

shifting from southern Spain to north Africa, at the time of the African

emperor Septimius Severus. I’ve put the title of my novel The Last Gospel in the blog heading because the Plemmirio wreck was

the inspiration for the shipwreck of St Paul in that story; diving down the

cliff base deep below the Severan wreck, Jack and Costas discover another,

fictional wreck, of the 1st century AD, including an amphora with an

inscription that clinches the ship’s identity and allows them to set their

sights on Paul’s ultimate destination, the city of Rome itself.

A sherd from the shoulder of an Afriocano Grande amphora with the remains of an inscription - perhaps in pitch - that may read EGTTERE, probably meaning 'to go.' Inscription approx. 16 cm across.

In our deep-water

explorations beyond the Plemmirio wreck we did indeed find evidence of other

wrecks, ranging in date from Archaic Greek to Byzantine, and on the Plemmirio wreck

we made the discovery that inspired the fiction - one of the Africano grande amphoras

with a painted inscription probably reading EGTTERE, an infinitive almost certainly meaning ‘to go.’ Unlike the minutely detailed inscriptions

found on Spanish oil amphoras of the 2nd century, designed to be

read and deciphered only by administrative officials, this was a big, bold

inscription on the shoulder of an amphora, meant to be seen from a distance and

instantly understood by those hurrying around a harbour front. I’ve little

doubt that it marked a batch of amphorae corralled together and destined for

export. To me, there could be no better

example of the use and extent of literacy in the ancient world – the

dockworkers at the lower end of the socio-economic scale who saw this might

only have needed to read a smattering of words to carry out their jobs, but if

they could read this then the chances are that more of them were more generally

literate than we might have supposed.

An Africano Grande amphora with the stamp ending PP visible on the neck.

A small portion of finds from the Plemmirio Roman wreck, including four pottery oil lamps along the top of the box.

That

graffito wasn’t the only inscription that we found on the wreck. One of the Africano grande amphoras was stamped on

the neck before firing with letters ending PP,

probably a Praetorian Prefect responsible for amphora production near the olive

estates and fish-salting installations along the African coast. Whether or not the Plemmirio cargo included a

state consignment, perhaps of oil, can never be known for certain, but this

stamp is vivid evidence of the extent of state involvement in amphora

production and the stimulus it provided to commercial trade. A third find was

the maker’s stamp IVNDRA on a

beautiful pottery oil lamp found among the ship’s galley stores. We think that

Iunius Draco was a lampmaker working in Italy, perhaps in Campania – within

sight of Vesuvius, a century or so after the eruption when Pompeii and its

brothels were but a distant memory. These two stamps, on the amphora and on the

lamp, are themselves fascinating evidence in support of Ward-Perkins’ thesis,

but for me that painted inscription is the most telling of all – something

quickly painted on the amphora perhaps by a foreman on the wharfside, and

surely also understood by the sailors who perished with the cargo against the

cliffs of Plemmirio south of Syracuse some time around AD 200.

Two of the pottery oil lamps from the wreck, the lower one stamped IVNDRA (probably Iunius Draco) (drawing: David Gibbins).

For

scholarly reports on these finds, see Gibbins 2001 and 1991c in this list.

September 22, 2013

TOTAL WAR ROME: Ancient Rome and the destruction of Carthage: the stuff that dreams are made on

Click here to read my blog on Tor.com, the site for fantasy fiction under the aegis of my US Total War Rome publisher Macmillan.

September 16, 2013

PHARAOH: The Journals of General Gordon of Khartoum

One of the

great pleasures for me in researching my novel Pharaoh was acquiring an original copy of General Charles Gordon’s Journals, covering his final months as

Governor-General in Khartoum in 1884-5 before the city was overrun by Mahdist

forces and he was killed. I’d wanted to find out more about his archaeological

and ethnographic interests, but I found myself utterly absorbed by his

day-to-day management of the city and the problems he faced. Unlike his other

published work of the period, Reflections

in Palestine, put together by admirers on the basis of private notebooks

from the year he had spent on leave in Palestine in 1883, the Journals were intended from the outset

to be read by others, and had been despatched to safety from Khartoum with

express instructions that they were to be edited appropriately. I’m certain that he

would have been appalled by Reflections,

a work of hagiography that he probably never saw – it was published in 1884,

when he was already besieged in Khartoum – and which did much to bolster the

image of Gordon the mystic that has clouded popular perception of him ever

since.

Those

expecting anything of this sort in the Journals

will be disappointed. I’ve often wondered whether Joseph Conrad had Gordon in

mind when he created his character Kurtz in Heart

of Darkness (1899), and certainly one take on Gordon has him staring

half-crazed out of his compound surrounded by hanging corpses and the stench of

death like Marlon Brando's Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse

Now, strongly derivative of Conrad. But when Martin Sheen in the film famously tells Brando ‘I don’t see

any method at all,’ the connection for me with Gordon is broken. The Journals

reveal Gordon as a consummate professional, with a great deal of method. Gordon was charged - had charged himself - with

the governance of a city on the edge of starvation and insanity, squalid and

desperate almost beyond belief but that he could just sustain by rationing out

food and medicine from his dwindling supply, keeping up hope by showing that he

himself had not lost it. They reveal a man of immense, almost sleepless energy – the Journals themselves are a considerable

achievement, running to several hundred thousand words, let alone the work they

describe – and of enormous passions, yet who channelled his frustrations into

practical measures where he could. By seeing his vitality, I began to

understand how he attracted such close friendships and admiration among those

who did not actually have to try to bring him under their control.

Much of what

preoccupied Gordon as Governor, and fills the pages of the Journals– ranging from sanitation and hygiene to siege

fortifications, range-finding for rifle fire and daily accounting of ammunition

expenditure – he had learned early on in the Corps of Royal Engineers, in the

two-year course that all newly commissioned sapper officers had to attend at

the School of Military Engineering at Chatham. The Royal Engineers attracted a generally

higher intellect than other branches of the army, and officers

ambitious for field experience could see much campaign service and rise to high

command. The Gordon Relief Expedition included more than seventy R.E. officers,

including Major-General Sir Gerald Graham, V.C.; Colonel Sir Charles Wilson,

Lord Wolseley’s intelligence chief who ended up in command of the ‘desert

column’ after its general had been

been killed; Major Horatio Kitchener, Wilson’s intelligence deputy and future nemesis

of the Mahdi, who I’ve blogged about here; and many junior officers with their

sapper companies carrying out survey, railway building, boat maintenance and

other engineer tasks. When I came to create a fictional protagonist with the

expedition it seemed right that he too should be a Royal Engineer, not

least because many of those men knew Gordon personally and their sympathy for a

fellow officer helped to focus my story on Gordon himself and what was really

going on in Khartoum.

'The Death of General Gordon at Khartoum, 26 January 1885' by George Joy (1893). In this version of events, Gordon is standing coolly on the balcony of the Palace, about to receive a fatal spear-thrust; other accounts by Sudanese eyewitnesses suggest that he died fighting inside the building, using his early-model Webley revolver and his Royal Engineers officers' sword.

My own fascination

with Gordon, as with Kitchener, stems from my boyhood, when my grandfather told

me that his grandfather – a Royal Engineer Colonel, Walter Andrew Gale – had known

both. While on the staff at Chatham in

the 1890s my great-great grandfather had been chair of the ‘Gordon Relics

Committee’, an attempt by the Royal Engineers to look after Gordon’s legacy;

the fruit of their work was an exhibit in 1897 at the Museum of the Royal

United Service Institution in London, including artefacts from the Sudan that can

be seen today in the Royal Engineers Museum. Gale also edited the Proceedings of the Royal Engineers Institute,

and flipping through those compendious volumes, full of scholarly papers on all

manner of subjects, made me appreciate better the professional focus of an

officer like Gordon. His passion for

antiquities was shared by many of his fellow officers – often with a biblical

backdrop – and drove a fascination with Palestine, Egypt and the Sudan that

bolstered their own Christian morality, in Gordon’s case strengthening his belief in his

role as saviour of the Sudanese people even if it was ultimately a doomed cause.

As for the

manner of Gordon’s death, the famous painting by George Joy shown here may not

be that far from the truth. The few eyewitness accounts are of uncertain

reliability, but suggest that he donned his dress uniform and met the enemy with

sword and revolver in hand. In so doing he was following the prime directive of

his Corps, to be a soldier first and engineer second. Gordon may have been a

man of profound religious leanings, veering towards the messianic at times, but

when it came to it the evidence suggests that he did not welcome death like a

martyr but instead went down fighting, a soldier rather than a prophet, a man upholding the professional ethos of the

Corps of Royal Engineers to the very end.

The final surviving entry of Gordon's Journal, showing his famous last sentence and the quirky footnote - unusual to the end! My belief that he must have resumed his journal in the five weeks before his death forms a major part of the archaeological trail in Pharaoh and its sequel Pyramid.

August 29, 2013

TOTAL WAR ROME: free maps preview

I'm delighted to be able to show two maps that appear in Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage, produced by my publisher Macmillan. The first one is a superb topographical map of the Mediterranean region showing the main settings of the novel - Rome, Macedonia, Spain and North Africa. The second is a plan of ancient Carthage showing the direction of the final Roman assault in 146 BC, from the harbours and the sea wall towards the 'Byrsa' and its temple. One the way you can see places that figure in the novel - the Tanit sanctuary, where the Romans witness horrific scenes of child sacrifice, and the old Punic quarter beneath the Byrsa, scene of savage fighting as the Carthaginians made their last stand. Rather than being a hypothetical reconstruction of its appearance at the time, I wanted the harbour complex to appear as it does today, including offshore foundations examined by diving teams under my direction in 1993.

Maps from Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage by David Gibbins

Copyright © 2013 David Gibbins

First published in 2013 in Great Britain by PAN MACMILLAN and in the US by ST. MARTIN’S PRESS/THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS

August 28, 2013

PHARAOH: the sarcophagus of Menkaure and the wreck of the Beatrice

This image of the north face of the Pyramid of Menkaure was made in 1842, only five years after Colonel Vyse's explorations. It shows the damage caused in 1196 by Saladin's son, Malek Abd al-Aziz Othman ben Yusuf, whose attempt to dismantle the pyramid created the gouge you can see above the modern entranceway and stripped away much of the façade. Vyse added to the damage by using gunpowder to blow his way through to the burial chamber.

The

present-day action in my novel Pharaoh

opens with Jack Howard and his IMU team diving deep into the Mediterranean in

search of a 19th century shipwreck thought to contain a fabled sarcophagus

from ancient Egypt. Their search is based on fact: the ship was the Beatrice, a British merchantman lost in

1838, and the sarcophagus was the stone coffin of Menkaure, pharaoh of the 4th

Dynasty of the Old Kingdom who died about 2500 BC. Only months before the

wrecking the sarcophagus had been found in the Pyramid of Menkaure - the smaller of the three

pyramids at Giza – by a British adventurer, Colonel Howard Vyse, whose account

of the discovery, Operations carried out at

the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, can be read here. The sarcophagus was empty

and had been damaged by graffiti, but it’s hard to take seriously his claim

that he was rescuing it from ‘destruction’ when he made the extraordinary –

some might say appalling – decision to remove it and ship it to the British

Museum. With difficulties ‘not trifling’,

his assistant and their Egyptian team inched the

three-ton sarcophagus out of the chamber and up the entrance passageway, using

rollers, a ‘crab’ and sheer manpower, damaging it on the way; at last it

reached the open air, and after what must have been an equally arduous

hundred-mile trek it was finally embarked at Alexandria on the Mediterranean

coast in the autumn of 1838, never to be seen again.

This and the other illustration below from

Colonel Vyse’s book are the only known record of the sarcophagus of Menkaure.

Although seemingly austere by comparison with later Egyptian

sarcophagi, it is of great importance for its age - almost 1200 years older, for example,

than the sarcophagi of Tutankhamun - and as one of the best exemplars of

the architectural style of decoration prevalent in the Old Kingdom.

The Beatrice is perhaps the most beguiling

unresolved case of a shipwreck containing a treasure much older than the date

of the sinking. Some of the most spectacular underwater discoveries have been

artefacts much older than the ships that were transporting them, whether

smaller items being carried privately as treasured heirlooms or the wholesale

shipment of looted works of art and antiquities. While I was an Adjunct

Professor of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology in Turkey I was fortunate to

handle material in the Bodrum Museum under conservation from the Bronze Age Uluburun

wreck, including a decorative stone sceptre-mace, seen here, that has is closest parallel

in a bronze mace from Romania – far from the East Mediterranean and Aegean

origin of much of the assemblage – and may have been considerably older than

the wreck, perhaps the first clear example of an heirloom or ‘antiquity’ being

transported by sea.

Over a

thousand years later, and fifteen hunded miles to the west, the Riace bronzes -

found off the southern Italian town of that name in 1972 – were part of a huge

traffic in works of art looted by the Romans after their conquest of Greece, some

of them dating back to the classical period and destined to adorn the public

places and private houses of their new Roman owners. Another great phase of

looting took place in the 18th and 19th centuries when

the ‘Grand Tourists’ shipped off many of the artefacts that populate European

museums today, ranging in size up to entire temple façades. Like their Roman antecedents the ships they

used were sailing vessels and therefore similarly vulnerable to wrecking. The

best-known example, discovered by divers, was HMS Colossus, wrecked in 1798 in the Scilly Isles off south-west

England while she was transporting Sir William Hamilton’s priceless collection of

Greek vases from Naples to London. The thousands of fragments now in the

British Museum represent a triumph of underwater salvage, but they are also testament

to the avariciousness of an age when collectors were willing to risk loss and

destruction of antiquities on this scale.

A huge timber raft on the Ottawa river below the Canadian Houses of Parliament in the 1890s, the same source of Canadian timber that had been used to build the Beatrice at Quebec some sixty years earlier.

The whereabouts of the Beatrice has bedevilled archaeologists for decades. The only solid

clues come from the account of Vyse himself, who in that same footnote – with no

word of regret – states that the ship had left Leghorn (Livorno in north-west

Italy), presumably a port-of-call on the way home, and then was ‘supposed to

have been lost off Carthagena’ in south-west Spain, as ‘some parts of the

wreck were picked up near the former port.’ In order to build up my own picture

of the ship I researched her in Lloyd’s

Register, often the only source of details on British merchant vessels

of this period. There are several vessels named Beatrice in this timeframe, but the most likely, whose owner and

master was a man named Wichelo, was a brig of some 224 tons built in 1827 which

had been involved in the transatlantic trade with general cargo between Quebec

and England in the early 1830s, as well as in the Mediterranean; at the time of

her loss she had been classified as ‘second description of the first class,

well and sufficiently found,’ having earlier been modified to snow-rig, been

copper-sheathed on two occasions and having had iron instead of wooden knees to

hold up her deck timbers.

I was fascinated to discover that she had been built in Quebec - a serendipitous connection with another aspect of my research for Pharaoh that I touched on in my previous blog, about the background of the Iroquoian Mohawks on the 1885 Nile expedition, as boatmen who had guided the log booms down the Ottawa river from the northern forests of Ontario to the port and yards of Quebec, where the timber was used for shipbuilding.

This level of detail allowed me to picture in the novel how the

wreck might be discovered – having found out that she had iron knees, and

guessing that she still would have been armed with cannon at this period, not

long after Barbary piracy had been suppressed, Jack and his team are able to

use magnetometers in their search. It also helped me to understand how the

wreck might have occurred. Although she was rated as seaworthy enough

and Wichelo had been her master for several years, she was not a

specialised stone-carrier like the ancient Roman lithegoi, nor is there any evidence that she had been used for a

similar purpose before. Inexpert lading of the sarcophagus could have greatly

affected her sailing characteristics. It’s possible to imagine how, being blown

suddenly towards shore on a southwesterly coastal route from Livorno towards

Gibraltar, Wichelo could have ordered her crew to to change course south with the

wind to larboard, a manoeuvre that might normally have saved the day but with the

ship heeling over could have caused the sarcophagus to shift, making recovery

impossible. Instead of being driven against the shore, she could have swamped

in deep water close to the coast – off Cartagena the rocky shoreline drops off

quickly to abyssal depth – leaving only flotsam to wash ashore, and thwarting

all attempts in modern times to discover her in depths accessible to compressed-air

divers.

What is certain is that somewhere in the west

Mediterranean one of the greatest lost treasures of ancient Egypt remains to be

discovered. Being of basalt the sarcophagus may be in an excellent state of

preservation, less vulnerable to seawater degradation than limestone. If the

sarcophagus of Menkaure were ever to be found, I know where I’d like to see it

go – back inside the pyramid at Giza where it belongs.

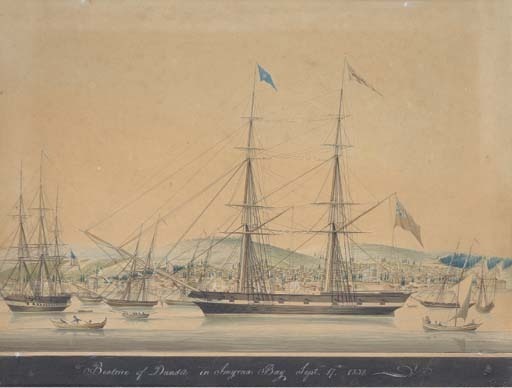

This

watercolour, entitled Beatrice of Dundee

in Smyrna Bay, September 17th, 1832, is variously attributed to

the Marseilles marine artist Mathieu-Antoine Roux (1799-1872) or the Turkish watercolourist

Raffaele Corsini. Despite also being a brig and being present in the

Mediterranean in the right decade – Smyrna is modern Izmir in Turkey – it seems

likely that this vessel is another Beatrice,

recorded elsewhere as trading out of Dundee and like the other Beatrice also being involved in

transatlantic traffic, taking passengers to New York in 1830. The Beatrice of Dundee was smaller,

recorded at 174 tons, but this picture gives a good impression of how the larger Beatrice might have looked, with the

same basic rigging and the line of gunports.

August 27, 2013

PHARAOH: canoeing in the Great Lone Land

I’ve just

returned from a canoeing expedition with my daughter in Algonquin Park, a huge

expanse of more than 7,600 square kilometres of forest and lake in central

Ontario first mapped by Royal Engineers surveyors in the 1820s and 1830s. At the time, the main interest was in finding

a new route from the Ottawa River west to Georgian Bay on Lake Huron, but as

any modern canoeist will attest that was never going to be feasible – there are

too many portages! Instead the region became a focus for logging, much of it to

supply the British shipbuilding industry, until that was stemmed by the

creation of the park in 1893 and the preservation of large tracts of wilderness

that remain today, with abundant populations of bear, moose and other wildlife, much of it only accessible by canoe and portage.

My novel Pharaoh was very much in my mind

throughout our trip, and the extraordinary fact that the Nile expedition of

1884 depended on Canadian voyageurs of aboriginal descent who had learned their

skills on lakes and rivers very similar to those that my daughter and I were

traversing. The backbone of the Canadian contingent in Lord Wolseley’s force

was a group of some 60 Iroquoian Mohawks from the Ottawa Valley, men who had

specialised in navigating the huge log booms down the river from the dammed-up

lakes and rapids that still preserve evidence of their efforts in the eastern

part of the park today.

But it was

their canoeing skills that had so beguiled Wolseley, fourteen years earlier on

the Red River expedition when he had led a force across the Great Lakes and up

the Winnipeg River to counter the rebellion of Louis Riel. In his autobiography

Wolseley describes making the descent of the Winnipeg river ‘… in a birch bark canoe manned by Iroquois

Indians, the most daring and skilful of Canadian voyageurs.’ He was horrified and thrilled when their sternman took them out into the centre of the river before

shooting a rapids: ‘ … nothing could have saved us from destruction had that

paddle broken when he held on to it in the current – as if it were a fixed iron

pillar – to draw the canoe’s head in towards the shore. Nothing pleases or satisfies

these Iroquois more than such trials of strength, such victories over dangerous

water, which is truly their element.’

It was that

exuberance and risk-taking that caught the imagination of the British officers

on the Red River expedition, a number of whom were brought together again for

the Nile. One of them, Colonel William Francis Butler, was a colourful raconteur

of both expeditions, and in his book The

Campaign of the Cataracts he describes his excitement at spying an old

friend one day on the Nile in November 1884, as he was overseeing the fitting

out of the whaleboats for what lay ahead: ‘... hugging the back-eddy of the

muddy Nile, a small American birch-bark canoe, driven by those quick

down-strokes that seem to be the birthright of the Indian voyageur alone … in it was William Prince, Chief of the Swampy

Indians from Lake Winnipeg; fourteen years earlier, on the Red River Expedition

in western Canada, he had been the best

Indian in my canoe … still keen of eye and steady of hand as when I last saw

him standing bowman in a bark canoe among the whirling waters whose echoes were

lost in the endless pine woods of the Great Lone Land.’

James Deer

(Sak Arakentiake), of the Kahnawake Mohawk of Ontario, who joined the

1884 Nile expedition aged eighteen and later wrote an account of his experiences, The Canadian Voyageurs in Egypt. He was

one of the few Mohawks who spoke English well enough to act as an interpreter

for the British, and gave talks on the Nile Expedition as late as the 1930s.

To Wolseleys’

delight, the voyageurs had brought along a second birchbark canoe from Canada

as a present for him, a boat he treasured and later enjoyed paddling on the

River Medway in England when he was Commander-in-Chief of the British army. On

the Nile, though, the Mohawks were required not to manage the large canoes of

the Red River expedition but instead the whaleboats that had been specially

built for the task, with a sturdiness better able to withstand enemy fire but a

consequent increase in weight and bulk that hugely exacerbated the task of

hauling them up the cataracts; nevertheless, had the expedition not been delayed by

political diffidence and machinations in London – the dark truth of which forms

a backdrop in my novel – they might have made it up the river before the level

of the water had fallen, and even reached Gordon in Khartoum before the forces

of the Mahdi closed in.

The failure

of the river expedition was thus not through any want of skill or effort on the

part of the Mohawk boatmen, who returned home with the approbation of Wolseley

and his lifelong appreciation. Their contribution should not just be seen in

terms of the success or failure of that expedition; Wolseley’s formative

experience in Canada in 1870, and the tight band of officers he formed around

him then – the so-called ‘Ashanti Ring’, but in reality derived from the Red

River expedition – shaped his subsequent campaigning in eastern and southern Africa

as well as in the Sudan, influencing the history of that continent in ways that

remain with us today.

My daughter

and I paddled in from Canoe Lake, famous for its association with Tom Thompson,

one of the ‘Group of Seven’ painters,

and then portaged our way far into the interior, camping on the ‘pristine

wooden islands’ that Butler had so loved in the west of Lake Superior in

1870. Our canoe was made of Kevlar,

rather than birchbark, but in all other respects owed everything to the native

craft it copied, including the beautiful incurving lines of the bow you can see

in the photographs. I first went on a canoeing expedition to Algonquin with my

father when I was ten years old, and certainly know what Wolseley meant when he

wrote of holding on to the paddle in a current, and Butler on the draw of the ‘Great

Lone Land.’

‘Canoe

manned by Voyageurs passing a waterfall’, painted by Frances Anne Hopkins in

1869. Hopkins was an English artist

married to an official of the Hudson’s Bay Company who accompanied her husband

on his travels into the Canadian interior, depicting them together in her

paintings – as here, in the centre of the canoe. Her attention to detail and

personal experience means that her paintings give a valuable picture of

voyageur canoes at the time of the 1870 Red River Expedition.

August 25, 2013

Video: shooting an original flintlock Sea Service pistol

In my blog

about the author Patrick O’Brian I included a picture of me holding a flintlock

Sea Service pistol, the same type that you can see Russell Crowe wielding as

Captain Jack Aubrey in the film version of Master

and Commander. In the film the enemy

ship is French, the Acheron, whereas

in the novel it’s American, one of the superb new frigates that faced the

British at sea and on the Great Lakes during the War of 1812. Since its

anniversary last year that war has received long-overdue attention in Canada,

with focus on the achievements of the British forces and the local militia –

many of them from loyalist families who had moved north from the former

American colonies – in resisting American incursions into Upper Canada, and in

taking the fight as far south as Washington DC. I’ve always been fascinated by

the inland naval aspect of that war, so acquiring a weapon that may have remained

in Canada since that time has added poignancy for me.

If you click

on the video image below you can see a short film of me loading and shooting the

pistol, taken with a GoPro camera mounted on my head to give a shooter’s eye

perspective. Sea Service pistols of this

pattern were manufactured between 1801 and 1812, by which time some 27,800

pairs had been produced. Alongside India

Pattern ‘Brown Bess’ muskets, they’re probably the most common surviving weapon

from the Napoleonic Wars period.

Handling this pistol, weighing a hefty three pounds, with its foot-long

barrel and massive brass-capped butt, brings home the ferocity of the hand-to-hand

fighting portrayed so vividly in Master

and Commander; once the pistol was discharged it could be reversed and used

as a club, to devastating effect. If you look closely at the forestock of my

pistol you can see a split, expertly repaired at the time, that looks like damage

that might have been caused by that type of close-quarters action.

The pistols

themselves were undated, and further precision in dating can only come from the

known dates of the manufacturers who often stamped their names on the underside

of the barrel or lock plate. In the close-up of the barrel you can see the stamp

I. GILL, one of a well-known family of sword cutlers and gunmakers who worked

in London and Birmingham throughout this period. The splendid trade-card opposite, dated from

1806, may mark their first contract with the Board of Ordnance, and therefore

provide a terminus post quem for my

pistol. If so, it was too late to have seen service the Battle of Trafalgar or

the earlier fleet engagements of the Napoleonic Wars, but is very likely to

have been in naval use at the time of the War of 1812.

In the

picture below right you can see the trigger guard stamped with the number 59, probably the rack number in a shipboard store

or of its Royal Marines contingent, or of a naval shore establishment. It’s

rarely possible to be certain about the history and use of a particular weapon

of this period, but in this case the chance that this pistol was present and

perhaps even in action on the Great Lakes in 1812-14 adds a historical frisson

to shooting it again, some two hundred years later and not far from those shores.

August 18, 2013

PHARAOH: free chapter preview

I'm delighted to say that my UK publisher Headline have put up a free chapter sample from Pharaoh on their website, in advance of the UK paperback publication next month. Click anywhere on the jacket image below for a free download. The excerpt comes from a chapter about a third of the way through the novel. Earlier, Jack and Costas had made an astonishing discovery in the Mediterranean, searching for looted Egyptian antiquities on a 19th century wreck. What they find takes them up the Nile beyond Egypt to the deserts of the Sudan, to a place inundated by the waters of the Aswan Dam that provides clues not only to an ancient Pharaoh but also to a British officer whose mission in the 1880s becomes part of Jack's own quest. Read more to follow Jack and Costas on of the most incredible dives of their careers ....

The paperback of Pharaoh is published in the UK on 26 September and in the US on 1 October; the UK hardback and ebook are already available, as is the hardback of the French edition from Editions les Escales. To find out more from my publishers, visit my author pages at my UK publisher Headline and my US publisher Bantam Dell.

To read another excerpt from Pharaoh, click here. To read a free chapter preview of Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage, click here.

August 17, 2013

Tobermory: diving the wreck of the Alice G

I took these

pictures yesterday of my daughter free-diving on the wreck of the Alice G at Tobermory in Canada, during a

few days spent exploring the pristine waters of Lake Huron at the end of the

Bruce Peninsula. The Alice G is one of some 22 known wrecks

in Fathom Five National Marine Park, a unique example of a national park

focused largely on the conservation of shipwrecks. To visitors, the forested wilderness and

uninhabited shorelines can seem at odds with the presence of so many wrecks, but

in the 19th century the treacherous neck of water between the main

body of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay was a conduit for the transport of timber

and other raw materials down the lakes towards the more populated parts of Canada

and the United States, in ships differing little from seagoing vessels. Some of the best-preserved examples of

schooners and barques of the late 19th century lies within the park,

their wooden timbers perfectly preserved in the cold fresh water; one of them,

the Sweepstakes, we also visited

yesterday, photographing it in kayaks from the surface. The picture below of the bows shows the extraordinary preservation of the ship, lying in only a few

metres of water with its 30-metre length almost completely intact.

The Alice G is one of a cluster of small

wrecks just outside Tobermory harbour that represents another aspect of the

lake economy, fishing. Built in 1902, a wooden-hulled steam screw tug some 20

metres in length, she was wrecked in a storm in 1929 and remains where she sank

against the shoreline, with most of the wreckage lying in less than 8 metres of

water. The wreck has special significance for me as this was where I carried

out my first open-water dive, in 1978 at the age of fifteen; the image of her

timbers and machinery lying on the lakebed has inspired several scenes of

wrecks in my fiction, including a 19th century Nile river steamer in

my most recent novel Pharaoh.

A view over Fathom Five park, with the harbour of Tobermory to the left, the open water of Lake Huron beyond and Georgian Bay to the right. The wreck of the Alice G lies in the centre foreground.

For me, all

wrecks, no matter how easy to access, have an edge to them. I’m always conscious

of the violence and fear they represent, and the proximity of danger. Yesterday

kayaking far offshore we could see the open reach of the lake on the western

horizon, and feel a touch of breeze that more than eighty years ago might have

signalled the storm that wrecked the Alice

G. ‘Great Lakes’ is really a misnomer; these are inland seas, as lethal in

their rocky reefs and violent weather as any ocean. And underwater, just out from the swimming-pool

conditions of the wreck, I dived down over a rocky ledge into another world

altogether, through the icy shock of the thermocline into nothing but grey

silted gloom. It’s yet another world at night, captured beautifully in the

film below by my brother Alan during a dive we did on the wreck in October a

couple of seasons ago, not long before the lake began to freeze up for winter.