David Gibbins's Blog, page 10

February 13, 2014

Murder in Jhansi, 1915

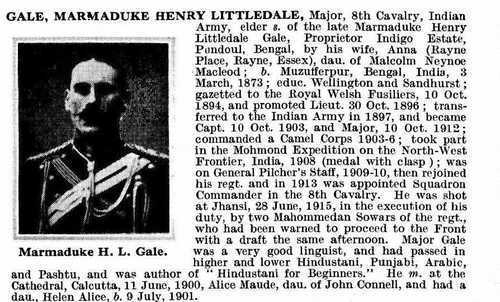

A few posts back I wrote of the First World War death of one of my great-great uncles in France in 1914. Another death on the other side of my family is recounted in the press release opposite, from July 1915. Two Muslim sowars – cavalry troopers – went on a murderous rampage in Jhansi in central India and killed four of their British officers, including my grandfather’s first cousin Marmaduke Gale. Their regiment, the 8th Cavalry, had been kept in India for internal security duties rather than being sent overseas. It was a similar incident in some respects to those experienced in recent years by coalition forces in Afghanistan with rogue Afghan soldiers. The British dead were buried in Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery, among 78 military deaths from the two World Wars commemorated there by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

The motivations behind this incident can never be known for certain, especially as the two perpetrators were themselves killed. One report suggests that they were disaffected after having been detailed to join a draft for overseas service; the following year two entire squadrons of the 8th Cavalry refused to go to Mesopotamia to fight the Turks, on the grounds that they were fellow-Muslims. But for the press release to state that the Jhansi murder was a ‘completely isolated incident’ was being disingenuous. Across India there had been numerous ‘terrorist outrages,’ as the press called them, since the outbreak of war with Germany and Turkey in 1914, though this was the worst.

Some of these acts of violence were directly instigated by the Ghadr, the Sikh nationalist movement founded in California in 1911 that had strong support among Indians in the United States and Canada. Others, perhaps including the Jhansi incident, originated with Muslim groups. The spread of discontent by agents of these movements in the ranks of the Indian army greatly concerned the British, who feared a repeat of the revolt that had taken place in the East India Company army in 1857, the ‘Indian Mutiny.’ The terrible bloodshed inflicted by both sides in that conflict was a constant backdrop to events in India leading up to the final British withdrawal in 1947. During the First World War the British administration still felt it could contain the unrest punitively, and disaffection in the army was dealt with harshly according to military justice; after one incident in November 1914 when elements of the 23rd Indian Cavalry mutinied and attacked a local treasury, twelve of the men were sentenced to death after court-martial and executed.

The Indian nationalist movement was undoubtedly the main driving force behind most events such as the Jhansi incident. But the sudden upsurge in violence across India after August 1914 can also be seen as part of the wider war, and not just because the nationalists were taking advantage of British distraction. In Washington, the German Embassy provided funds and intelligence to the Ghadr movement, supplying them with thousands of rifles and millions of rounds of ammunition to mount a seaborne invasion of India. In Constantinople, the Ottoman regime in 1914 issued fatwahs ordering Muslims in India to rise in jihad against the British, another factor in the attacks. For these reasons, the authorities after the war saw the British military casualties of this violence as part of the wider conflict, and put their commemoration under the remit of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Marmaduke Gale’s background was emblematic of the British presence in India. He was the fifth generation of his family to have been there, the first having been an officer on an East Indiaman in the late 18th century and the next a Lieutenant-Colonel in the East India Company’s army. Marmaduke’s grandfather, my ancestor John Gale, owned the largest indigo plantation in India, the ‘factory’ at Pundaul mentioned in the biography below, where my great-grandmother and her father were born. The conditions of work on the indigo estates led Mahatma Gandhi famously to visit them in 1919, when one of the planters he confronted was Marmaduke’s cousin Maurice Gale – though in circumstances of non-violent protest that were to prove a more effective agent for change than the terrorist incidents of a few years before.

For a long time after the British left India the Jhansi Cantonment Cemetery was neglected, becoming overrun with vegetation and snakes. In a happy footnote to this story a local Anglo-Indian, Mrs Peggy Cantem, undertook to clear out and tend the cemetery, working single-handedly into her eighties until joined latterly by representatives of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. You can read about her work here. The cemetery contains burials dating throughout the period of British rule in India, including the Indian Mutiny. The whereabouts of the graves of the two Indian brothers who died in this incident are unknown.

November 25, 2013

PHARAOH: firepower in the desert, 1884

The video below shows me shooting an 1882 Martini-Henry rifle, the weapon used in my novel Pharaoh by British troops against the forces of the Mahdi during the 1884-5 expedition to relieve General Gordon in Khartoum. That war was one of the last major conflicts fought using black powder, though with fast-action breech-loading rifles far superior to the muzzle-loading weapons that had been the mainstay of armies only twenty years previously. With reloading now taking only seconds, these new rifles allowed a disciplined force to lay down a withering fire almost as devastating as machine-guns were to be in wars to come; their accuracy also meant that sniping, or ‘sharpshooting’ as it was called, was now possible at ranges that were previously impossible, allowing my protagonist Major Mayne to use one of these rifles to pick off a dervish rifleman across the Nile more than 600 yards distant.

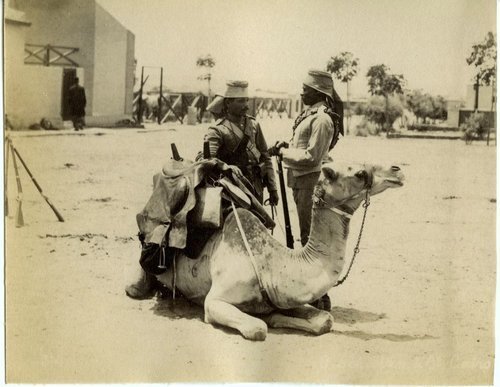

A rare photo from the 1884-5 Nile campaign showing troopers of the 11th Hussars in desert gear with Martini-Henry rifles.

Cartridges compared: .577/450 Martini-Henry, .303 Lee-Enfield and .22 LR.

The Martini-Henry disassembled, with Pattern 1876 bayonet as used in the Sudan.

The Martini-Henry fired a massive 480 grain .45 calibre bullet, projected by 85 grains of Curtis and Brown powder in a .577 bottle-shaped cartridge. The British experience fighting ‘fanatics’ during the Indian Mutiny of 1857-8 had led them to favour rifle and pistol rounds with maximum stopping power, and the .577/450 was the most powerful they ever adopted. The rifle action was an immensely strong ‘falling block’ actuated by a trigger-guard lever; pulling down the lever ejected the spent cartridge and opened the breech for the next round, and closing the lever raised the block and cocked the action. As a single-shot military rifle it was unrivalled, its main drawbacks being the problems inherent with black powder of excessive fouling and barrel overheating – problems only alleviated with the introduction of smokeless nitro propellants from the late 1880s, at a time when the Martini-Henry was rendered obsolete in British service by the introduction of the bolt-action .303 rifle that was to become the Lee-Enfield. Despite this, the Martini-Henry in a .303 version continued in use by colonial troops until well into the 20th century, and in Afghanistan was seen alongside Lee-Enfields in the hands of tribesmen as late as the Soviet war of the 1980s.

The Remington rolling-block rifle, with its breech open.

The Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers on the Nile were not armed with Martini-Henrys but instead with US-made Remingtons, ordered by the Egyptian government in the late 1860s. Chambered in .43 Egyptian, the Remington ‘rolling block’ was another ingenious breech-loading design: the block was a drum of steel that was snapped shut over the breech once it was loaded, and then locked tight when the trigger was pulled and the hammer closed over the drum before striking the firing pin. As the operation require three steps - manually cocking the hammer, thumbing open the block and then closing it - the Remington was a slower weapon to reload than the Martini-Henry, and the .43 Egyptian was a slightly less powerful cartridge. Nevertheless, it was an excellent, robust rifle, over a million being produced in various calibres by the Remington factory in New York State, providing rifles for buffalo-hunters in the American west – where it vied with the Sharps rifle - as well as for the many countries that adopted it as their military arm, including Egypt, Spain and Norway. Its widespread use across north Africa was a matter of ready availability, but it may also have been favoured by tribesmen because its distinctive shape in the grip area was similar to the slender flintlock and snaphaunce rifles that had been their mainstay in earlier decades, and continued in use well into the 20th century.

Egyptian soldiers in the late 19th century with Remington rifles.

Remingtons were also used against the British by Mahdist warriors who had picked up rifles from the battlefield. In 1883, before Gordon was appointed to Khartoum, the Egyptian governor of Sudan hired a former Indian army officer named William Hicks, remembered as ‘Hicks Pasha’, to lead a ragtag force of Egyptian and Sudanese troops - an army described by Winston Churchill as ‘the worst in the world’ – against the Mahdi, a doomed enterprise that resulted in their annihilation at the battle of El Obeid and thousands of Remington rifles falling into dervish hands. The dervishes are remembered from later battles such as Abu Klea for their suicidal charges and ferocity in hand-to-hand combat, but they had also became proficient marksmen and their Remingtons were responsible for the deaths of many hundreds of British, Egyptian and Sudanese government troops during the campaign.

Egyptian markings stamped into the barrel of the Remington.

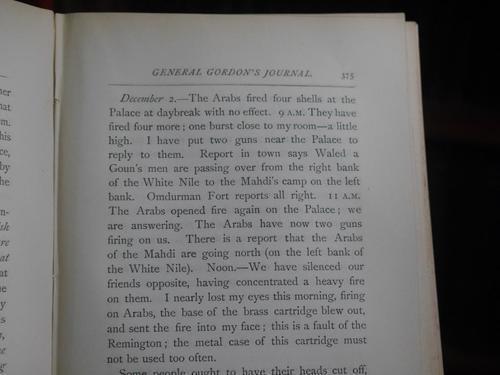

The Remington held by my nephew in these pictures well may be one of those rifles, its original Egyptian ownership revealed by the markings in Arabic script stamped above the breech. The lands of the rifling are worn down from extensive use, though the bore itself is shiny and well looked after - as would have been the case not only for government troops but also for Mahdist warriors well aware of the corrosive effects of black powder fouling if left uncleaned. I haven’t tried to fire this rifle as it has a slight loosening of the breech block; I’m mindful of General Gordon’s accident with a Remington while sniping at the enemy over the Nile, recounted in his diary entry opposite. The fault that he identifies was probably not with the rifle or with the cartridge but with the fact that his troops had reloaded the brass too often and weakened it, factory ammunition no longer being available to the beleaguered garrison. Nevertheless, unlike the British authorities in London who had turned a deaf ear to his warnings about the rise of the Mahdi, I’m inclined to heed his experience with the Remington and leave this rifle well alone, its potency for me lying instead in the episode of history that it represents and the ongoing ramifications of the Mahdi war in that part of the world today.

November 14, 2013

TOTAL WAR ROME: the triumph of Aemilius Paullus

This magnificent painting by Carle Venet depicts the triumph of Aemilius Paullus, the Roman general who defeated the Macedonians at the battle of Pydna in 168 BC. At that date, mid-way between the Second and the Third Punic Wars, Rome’s conflict with Carthage was still unresolved, but at Pydna she smashed the last remnants of Alexander the Great’s empire and opened the way for conquest of the East. A little over twenty years later Roman legionaries stood astride the towering crags of AcroCorinth and proclaimed rule over all Greece, and in the same year Paullus’ son Scipio Aemilianus took Carthage and secured Roman control over the west Mediterranean. Without Pydna it’s unlikely that either of those victories in 146 BC would have taken place as they did, so this painting represents one of the pivotal events of ancient history.

A detail of Venet's painting, showing Aemilius Paullus in his chariot and the horses that reminded me of the riderless horse in the Delphi frieze, shown below.

Carle Venet had studied in Rome and was familiar with its monuments and vistas. However, at the time when he was painting this, in the 1780s, the precise dates of many of those monuments within the Roman period were unknown, and would probably have been of limited interest anyway - backdrops such as the one in this painting were a kind of generic wallpaper for scenes of Roman history derived from reading the ancient authors. Here, in approximately their correct disposition, you can see Trajan’s Column, the Arch of Septimius Severus, and, beyond the Temple of Jupiter, the Colosseum – all of them monuments of Imperial Rome, constructed centuries after the triumph. Neverthless, it’s a hugely powerful work that seems to manifest everything we imagine about Roman splendour. One of its strengths artistically is that Venet broke with tradition and depicted horses naturalistically, based on his study of horses in his native France. Seeing this detail in the painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York sparked my memory of a monument that I often dwelt on when I taught Roman art – lecturing about a time when art too was undergoing a transformation partly as a consequence of Paullus’ victory. It led me to return to the ancient account that inspired Venet, the description of the battle and the triumph by the Greek historian Plutarch, and to think of how these events might form early scenes in my novel Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage.

The view from the slope of the Capitoline hill that Aemilius Paullus would have had as he watched the triumphal procession coming along the Sacred Way towards him, only for us obscured by the arch of the emperor Septimius Severus at the head of the forum. In front of the arch are all of the most hallowed places of the forum, including the Rostra, and to the right in this picture are the remains of the Basilica Julia, three columns of the Temple of Vespasian and the foundations of the palatial structures on the Palatine Hill, all of which date later than the time of the triumph when the slopes of the Palatine were occupied by aristocratic houses.Venet's vantage point when he was planning his painting would have been about two hundred metres to the right of where I took this picture, allowing him to see the sequence of monuments visible in the background of his painting.

Today, the place where you can best imagine the procession is in the very heart of ancient Rome on the slope of the Capitoline hill, and that’s where in my novel I have Scipio and his friend Fabius watching the procession - standing on the steps and contemplating the scene along the Sacred Way just as we can in the ruins of the Forum today, blocking out in our mind’s eye all of the later structures and accretions which make it look more of a jumble than it would have seemed in the 2nd century BC. To the Romans, those buildings that seem so emblematic of ancient Rome – the great temples and law-courts, even the Senate House, one of the few structures to remain in its original position as Scipio and Fabius might have seen it – were of less significance than the Sacred Way itself or the holy places close under the Capitoline at the base of those steps, sites such as the Rostra that seem so nondescript to visitors today yet were far more meaningful than many of the grander structures beginning to appear by the 2nd century BC in the forum.

Plutarch – writing about the end of the first century AD, but basing his account on earlier sources – famously catalogued the enormous plunder brought by Paullus from Macedonia. It's this that has led art historians to see the Pydna triumph as marking an intensification of Greek influence in Rome, with many Greek sculptures in bronze and stone now adorning Roman public and private places and their styles being copied by Greek artisans who had come to Rome in the wake of the triumph. The scale of the booty shown in the procession was huge – according to Plutarch ‘... the first day was just barely sufficient for seeing the statues that had been seized, and the paintings, and the colossal images, all carried along on 250 wagons drawn by teams’ – and yet today no surviving sculpture can be securely attributed to that event, with all the famous works of art thought to have been looted in 168 BC having been destroyed or lost in the course of time.

One remarkable survival does remain, however - the monument that figured large in my courses on Roman art, and which I remembered when I saw the horses in the scene by Venet. Soon after the triumph Aemilius Paullus had a monument erected in the Greek sanctuary at Delphi, symbolically placing it on a pedestal that had been intended for a statue of his vanquished rival, the Macedonian king Perseus. The monument was a tall stone pillar surmounted by a bronze equestrian statue and adorned with a sculpted frieze of a battle scene, fragments of which can be seen in the Delphi museum today. In my novel I imagined a mock-up of the monument by the Greek artist Metrodorus – a man we know from Plutarch to have been responsible for paintings of the battle - being a centrepiece of the triumphal procession, carried towards the steps of the Capitoleum so that the frieze at the top was at eye level with Scipio and Fabius and the others watching with them, and could be fully appreciated:

One of the scenes in relief sculpture on the Monument of Aemilius Paullus at Delphi in Greece, showing the riderless horse described by Livy and Plutarch in their accounts of the Battle of Pydna. This general style of sculpture was not a novelty in Greece, but what was new was the depiction of an actual battle rather than a veiled mythological scene - the beginning of a long tradition in Roman sculpture that was to reach its height in the military reliefs on the Column of Trajan, shown anachronistically in Venet's painting above.

It showed a battle-scene, with life-sized men pressing and lunging, hacking and stabbing. It was so realistic that Fabius felt he could walk right into it. Dying soldiers were shown on the ground with wounds laid bare, dripping with blood that must have been applied by Metrodorus just before the procession. In the centre of the melee was a riderless horse that Fabius remembered from Pydna, one that had broken free from the Roman ranks and galloped between the lines, stirring them to battle …

The riderless horse is one of the most striking and beautiful features of the frieze, its head arched away from the viewer as it rears up in the midst of battle. It was this horse that allowed art historians to pin the frieze to the Battle of Pydna – Livy, another ancient historian who mentions Pydna, also tells us that a riderless horse galloping between the lines precipitated the battle – and to see the sculpture as one of the first historical depictions in ancient relief sculpture, rather than a mythological battle scene. As the sculpture was made within living memory of the battle, it allowed me to feel that the accounts by Plutarch and Livy described a real event, and to write my own version of it into my novel. In this excerpt, the Paeligni, Italian allies of the Romans, have begun to surge towards the Macedonian lines, but already another of Scipio’s friends, the former Greek cavalry commander and future historian Polybius, had ridden forward to taunt the enemy – a fictional addition to the battle of a man who later insists that Metrodorus only show the riderless horse:

Another scene from the Aemilius Paullus monument, showing Roman and Macedonian soldiers distinguishable by their shields and other equipment.

The Paeligni had already begun their charge, bounding forward like wild dogs, making a noise like a thousand rushing torrents. They were running at astonishing speed, and the distance between them and the phalanx had already narrowed. Fabius could see Polybius making for the gap, his shield held out diagonally to the left, charging in a swirl of dust. Another horse had followed riderless, breaking away from the Roman lines until it overtook Polybius and disappeared into a storm of dust. For a horrifying moment it seemed as if he would not make it in time, as if the gap would close and he would hurtle among the horde of Paeligni warriors. But then he was gone, and all Fabius could see was a streak of silver along the line of Macedonian spears, as if a wave were passing along it.

You can read the entire text of the Prologue containing that battle scene here. It’s rare to find any corroborating physical evidence for an ancient account of a battle, but these few fragments of sculpture provide as vivid a connection as could be found and help to put the backstory to Venet’s painting into its true historical context.

Extracts copyright © 2013 David Gibbins from Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage (Macmillan, London and New York, 2013)

November 13, 2013

PHARAOH: French edition

Voici l’èdition française de mon roman Pharaon, publiée par Éditions Les Escales.

Égypte, 1351 av. J.-C. Akhenaton règne sans conteste sur l’empire ... jusqu’à ce qu’il disparaisse mystérieusement dans le désert et, avec lui, son héritage, englouti par les sables.

Soudan, 1885 apr. J.-C. L’Empire britannique lance une expédition pour sauver les troupes du général Gordon, barricadées dans Khartoum assiégé. Sur les rives du Nil, un soldat fait une découverte incroyable: un temple qui semble dédié à un dieu nourri par des sacrifices humains ...

Pyramides de Gizeh, de nos jours. L’archéologue-plongeur Jack Howard et son équipe fouillent l’un des plus impressionnants sites sous-marins jamais découverts. Vont-ils réussir à percer le secret du légendaire pharaon et de son trésor? Le début d’une formidable aventure au coeur d’un monde vieux de 3000 ans, avec, à la clé, des révélations qui pourraient changer le cours de l’histoire ...

“Qu’obtient-on en croisant Indiana Jones et Dan Brown? Réponse: David Gibbins” London Daily Mirror

À propos du Masque de Troie: “L'Iliade revue par Indiana Jones, Homère prolongé par un Dan Brown à l'imagination diabolique. À couper le souffle !” France Dimanche

Je suis docteur en archéologie, et l’auteur à succès d’Atlantis, du Chandelier d’or, du Dernier Évangeline, de Tigres de guerre, du Masque de Troie, et des Dieux d’Atlantis, tous repris chez Pocket (First Éditions).

November 11, 2013

The war to end all wars

A little over ninety-nine years

ago one of my great-great uncles died of his wounds near the river Aisne in

northern France, a few weeks after the outbreak of the First World War. He was

one of the ‘Old Contemptibles’, the regular soldiers of the British

Expeditionary Force which was all but destroyed by the end of that year, among

the first of some eight million men of all sides killed by the time of the

Armistice on 11 November 1918. Nine men in my immediate family were soldiers in

that war, including my mother’s father and his brother and three further

great-great uncles. They represented the gamut of the services –officers and

enlisted men, infantry, cavalry, gunners and sappers, a doctor and a chaplain.

Two of them were killed and two severely wounded, and for those who survived,

like my grandfather, their lives and that of their families were permanently

overshadowed by the war. I’m sure a similar family history could be told by

many of you reading this piece. For me, that shadow is still very immediate,

because my grandfather lived until I was in my twenties and I knew him well, so

that words like ‘Somme’ and ‘Passchendaele’ conjure up for me not just the

familiar images from old photographs but his detailed and often shocking

memories from two and a half years on the Western Front. I’ve been to many of the cemeteries tended by

the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in France and Belgium, places like Braine,

pictured below, where my great-great uncle from 1914 is commemorated – like many

his exact grave is unknown – and marvelled at the beauty and tranquillity of those

places, and of a landscape once so devastated by war. One this day, 11 November, I remember it as my

grandfather did, as Armistice Day, the day in 1918 that ended what he and his

generation knew as the Great War – the war that was supposed to end all wars.

A

view of the Commonwealth War Graves plot in Braine Communal Cemetery in

northern France. 6878 Private Ernest Reginald Handford, 2nd

Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment, my mother’s great-uncle, is

commemorated on stone B8 – eighth from the left in the back row – along with a

Lance-Serjeant of the 18th Hussars. The stones are ‘Special

Memorials’ rather than headstones, because the exact positions of burials in

this plot were lost some time after its use by No. 5 Casualty Clearance

Station, based in Braine during the advance along the river Aisne when Ernest’s

battalion saw its first action in France. The ‘South Staffs’ began the war with two

regular battalions, numbering some 1600 men; by war’s end the regiment had

suffered 6,551 men killed. Ernest was 34, had been a filer in a bicycle factory

before joining up, and left a wife and two small boys.

November 10, 2013

PHARAOH: a Canadian Mohawk on the Nile

Of all the

larger-than-life character portraits that have entered popular memory from the

1884-5 British Nile campaign – the future Lord Kitchener, a desert spy,

disguised as an Arab and carrying a cyanide tablet in case of capture; the wiry

and imperturbable General Wolseley, sticking to his plans against the odds; the

extraordinary Colonel Fred Burnaby, greatest adventurer of his age, wearing a

deerstalker and blasting away at the dervishes with his shotgun – none are more

impressive for me than James Deer, known to his people as Sak Arakentiake,

shown here in a photograph taken a few years after the campaign and the

inspiration for one of the fictional characters in my novel Pharaoh. He was a

Canadian Mohawk born on the Tyendinaga Reserve in Ontario and was one of 61

Iroquois invited to join the expedition by Wolseley, who had been so impressed

with their boating skills during his 1870 Red River Expedition in western

Canada. Originally the Mohawk had been part of the Iroquois Confederacy in what

is now New York State, and had fought alongside the British during the

Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 – to many the word ‘Iroquois’ still sends

a chill down the spine. But by the 1860s, resettled in Ontario and no longer

warriors, the Mohawk had applied their boating skills to the dangerous task of

bringing rafts of timber down the Ottawa River from the northern forests. James

Deer was one of the few Mohawk who spoke English well enough to act as an

interpreter on the expedition, and wrote an account published in 1885 as The

Canadian Voyageurs in Egypt; he was still giving talks about the expedition as

late as the 1930s. Despite their fearsome reputation the Iroquois on the Nile

were non-combatants, not once firing a shot at the enemy, but as boatmen they

won the admiration of all who served with them, and were among those who left

the Nile holding their heads high knowing they had done their best despite the

failure of the expedition to rescue General Gordon in Khartoum.

November 1, 2013

TOTAL WAR ROME: what it meant to look Roman

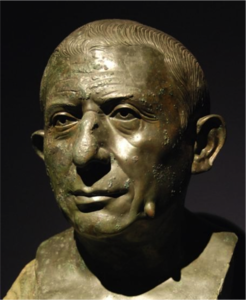

Sometimes called the 'Torlonia patrician', this sculpture in the Torlonia Museum in Rome is thought to date from the first half of the 1st century BC, and represents a tradition modern art historians call 'verism' - exaggerated realism, after the Latin verus, meaning 'truth' - that probably originated at least a century earlier.

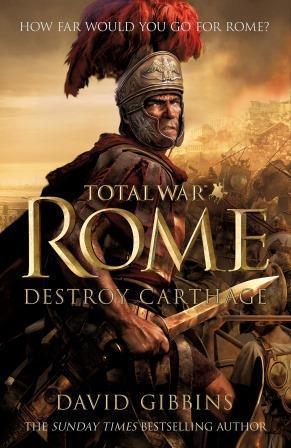

My novel Total War Rome: Destroy Carthage begins

in 168 BC at the Battle of Pydna, the decisive engagement in which the Roman

general Aemilius Paullus defeated a Macedonian army and secured Roman power in

northern Greece. The action then moves to Rome for the triumphal procession, a

massive haul of works of art and other booty being watched by Aemilius Paullus,

his son Scipio Aemilianus and the old senator Marcus Porcius Cato, whose cry

‘Carthage must be destroyed’ resonates through the novel just as it did in real

history. Before the prisoners pass by on their way to execution, there’s a lull

in the proceedings when Scipio’s friend, the legionary Fabius, sees the weight

of history fall on Scipio’s shoulders, as the older generation passes on the responsibility

for Rome’s future to the next:

‘While they

waited, Cato moved behind Scipio, his face craggy and lined, dressed austerely

in the old-style toga of his ancestors, looking disapprovingly at the cluster

of bearded Greek teachers below the rostrum who were trying to keep a class of

unruly young boys in order. As far as Fabius could tell, the only Greek whom

Cato had ever really approved of was Polybius, and only then because Polybius

was the foremost military historian of the day and one of Rome’s most vocal

proponents, so much so that Cato himself had called for him formally to be

released from his status as a captive and made a Roman citizen. Cato spoke

close to Scipio’s ear, but Fabius overheard. ‘When I was your age, I stood at

this very spot, over fifty years ago when Hannibal had crossed the Alps with

his elephants and was threatening Rome. Your father who stands beside us now

was like one of those boys below, though back then we used battle-hardened centurions

to show our boys how to be men, not these effeminate Greeks.’

The sculpture that gave us the expression 'warts and all', the head of a herm - a marble pillar showing nothing else except genitals - found in the house of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus at Pompeii. Anyone who has done the Cambridge Latin course will know this man and his family, though the coursebooks don't show the full detail of his herm! One of the great revelations of Pompeii and Herculaneum - like shipwreck finds of works of art - was the survival of bronze sculptures, as most bronzes from antiquity were melted down in subsequent centuries for their metal.

My image of

Cato was inspired by the ‘veristic’ portrait sculptures of the late Roman

Republic, in particular the famous example shown here from the Torlonia Museum

in Rome – an image that seems uncompromisingly realistic, of a man showing the

wear and tear of life to an almost exaggerated extent. When I first studied classical

art we were taught that this exaggerated realism was a distinctive feature of

Roman portrait sculpture, in contrast to the idealism of the Greeks, and that

this reflected Roman self-perception. I’ve been thinking about this again since

seeing the brilliant Pompeii and Herculaneum exhibition at the British Museum,

where sculpture was presented as if it were in a Roman house, to show art in

its original context. This reinforced to me just how much ‘Greek’ art in a

Roman setting was essentially decorative; the beautiful bronzes of goddesses

and nymphs around the pools and gardens stood in stark contrast to the phallic

herm of Caecilius in the centre of the room, the wart on his face almost a

provocation and his position showing what would really have been considered

important to the Roman owner of the house.

This bronze from the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum - a setting in my novel The Last Gospel - represents the idealised human form characteristic of Greek-style sculpture used as decorative art in gardens and courtyards.

We were taught that verism in Roman

portraiture may have derived from the aristocratic tradition of keeping representations

of ancestors in the house, in the form of wooden or wax portraits that were presumed

to bear a close likeness to the individual. One of the most fascinating

artefacts for me in the British Museum exhibition was a small wooden sculpture

thought to have been one of those ancestral images, revered in a household

shrine. Even taking into account the

depredations of time on wood, there seemed to me no way that such a sculpture

could bear anything like the detail of the ‘warts and all’ sculptures in bronze

or stone, and a moment’s reflection suggests that this must have been the case

for wax as well. It struck me that the sheer crudity of these sculptures may

have been deliberate, that they must have been fashioned in that way by

artisans almost certainly capable of better. The view we were taught could be

turned on its head: rather than representing a tradition of realism, ancestor-worship

could have involved a simplified depiction of the human form, itself a throwback to a nobler, more austere past – before, some like

Cato may have fancied, the Greeks came along and sullied it all – that Romans

were beginning to idealise as part of their foundation mythology.

A wooden statue - probably representing a female ancestor - from the House of the Wattlework at Herculaneum (height 30.4 cm).

A wooden statue probably of a male ancestor from the House of the Mosaic Atrium at Herculaneum (height 28 cm). This is of particular interest because it's a herm, with very schematic genitalia, and could therefore be seen as ancestral to the type of herm showing high-quality sculpting and 'verism' seen in the bust of Caecilius above - and yet this wooden herm is crude in the extreme and hardly a realistic ancestor portrait.

In truth, influence from the Aegean

world had reached Rome from the earliest times. To many Romans their primordial

warrior was the Trojan prince Aeneas, whose equipment, armour and fighting

skills would have been the same as those that provided the antecedent for the

military traditions of Greece in the classical age. The story of Aeneas may

largely have been a creation of the 1st century BC poet Vergil, but

it undoubtedly reflects a historical reality dimly remembered in the Roman

annals of the time - that of Bronze Age seafarers who came to Italy in search

of iron and other raw materials at the time of the Trojan Wars, setting the

stage for Greek and Phoenician colonisation in subsequent centuries. At a time

when Rome was little more than a collection of rude huts on the Palatine Hill,

their Etruscan neighbours were exchanging iron ingots for finished metalwork

from Greece, adopting Corinthian-style helmets and breastplates that continued

to be characteristic of Etruscan warriors centuries later. Rome grew as a city

in parallel with colonies established by Greek traders at places like Cumae and

Neapolis, trading with them and eventually absorbing them into her ever-growing

sphere of influence.

A shrine with crude images of ancestors from the House of the Menander, Pompeii.

It would be wrong therefore to think that the conquest

of Greece in the 2nd century BC was the first big exposure of Rome

to Greek art and culture. What it did, though, was to bring large numbers of

Greeks themselves to the city for the first time, whether as captives or as

opportunists, men like Polybius but also artisans who could cater for and

encourage a taste in Greek sculpture, painting and other forms as decorative

art, something seen so clearly two centuries later in the houses of Pompeii and

Herculaneum. At a time when Rome was expanding

but not yet an empire, when she was still ruled as a city-state and a republic,

the Greek influx not only made intellectual Romans – men like Cato - more

self-aware, but also pandered to the strong sense of conservatism in her ruling

class, for whom ‘the old ways’ – the mos

maiorum – was a clarion-call fuelled by the kind of anti-Greek sentiment I

have Cato expressing in my novel.

Individual works of art from antiquity can acquire undue significance in the eyes of some viewers as evidence for trends, and this one - the famous 'Togate Barberini', of the 1st century AD - may have spawned the idea that Roman ancestral images were highly realistic, showing as it does a patrician carrying what are probably meant to be wax portraits of his father and grandfather. Of course, this is a sculpture of exceptional quality, and the 'masks', too, have been executed superbly; it's hard to imagine wax images of this quality surviving beyond a few generations. The norm for ancestral images for most Romans was probably closer to the crude sculptures shown above from Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The

‘warts and all’ sculptures – craggy Cato, warty Caecilius - only possible, of

course, through the skill of Greek sculptors, can be seen as a kind of

exaggerated defiance, but also as something that was soon to be an immensely

powerful image of self-assurance, to the extent that it became the favoured

style of portraiture for many of the emperors of the 1st and 2nd

century AD. The same sense of self-assurance is seen on the cover of my novel, in

the snarling, defiant Roman soldier - a defiance no longer defensive, but aggressive

and supremely self-confident – that seems to us a quintessentially Roman image,

right down to the Greek-style armour and weapons with which he is set to

conquer the world.

October 20, 2013

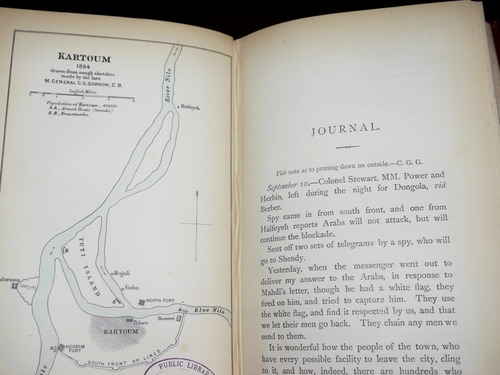

PHARAOH: the maps

I blogged last month about my pleasure in reading General Gordon's diary from Khartoum while I was researching my novel Pharaoh, and how I particularly relished his attention to detail - describing everything with an engineer's eye, and calculating quantities and distances as closely as possible. One great advantage of this was that I knew that I could rely on his sketch maps as a basis for the maps that my publisher Headline created for the novel, both of which are reproduced here along with a printed original from Gordon's diary - in the case of the larger-scale map of Egypt and the Sudan, with additional detail derived from the equally dependable maps in the official history of the Royal Engineers in the Nile campaign. I used Gordon's own range-finding as a basis for calculating the distance across the Nile between the North Fort and the Governor's Palace, one of crucial significance in my novel in the final fateful hours of Gordon's rule in Khartoum before the forces of the Mahdi break through into the palace compound and Gordon makes his last stand.

In this map you can see the short cut taken by the 'Desert Column' from Korti to Metemma, where they were meant to meet up both with the 'River Column' and the armoured steamers that had come down from Khartoum to take them upriver. In the event, the River Column never made it in time, and the Desert Column was stalled by the savage battle at Abu Klea and Abu Kru; the small force that was able to embark on the steamers for Khartoum arrived a day too late.

Key settings in my novel are the Governor's Palace on the south side of the Blue Nile and the North Fort on the opposite bank, to the east of Tuti Island. To the south you can see the defensive walls that Gordon attempted to strengthen, and on the west bank the fort of Omdurman where the main Mahdist force was encamped and where Kitchener fourteen years later exacted his terrible revenge for the murder of Gordon.

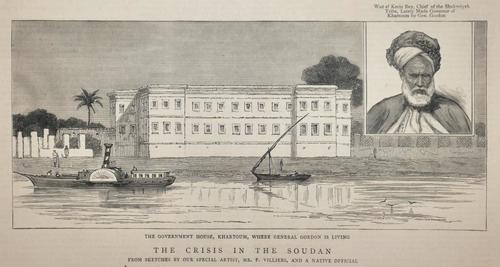

This engraving from The Graphic of 3 May 1884 gives a rare image of Government House, Khartoum - the Governor's Palace - as it looked during Gordon's occupation, including the entrance compound to the left and the muddy foreshore of the Nile at low water. The palace was used by the Mahdist forces during their years of occupation following the death of Gordon, and after the British reconquest in 1898 was demolished and replaced with a more lavish building.

An excellent modern aerial view of Khartoum showing the Presidential Palace - on the site of the Governor's Palace of Gordon's time - and across from it the site of the North Fort, with Tuti Island in the background and the Nile in flood.

October 7, 2013

PHARAOH: medals of the 1884-5 Nile campaign

The two medals awarded to British soldiers and sailors - and some civilians, including Canadian voyageurs - who took part in the 1884-5 Nile expedition. The Nile Medal, awarded for actions from 1882-9, has the clasp awarded to Sapper Mark Wright for being present with the expedition; had he fought in the battles of Abu Klea or Kirbekan he would have had clasps for those actions as well. The Khedive's Star shown here was also awarded to a participant in the campaign, with the dates 1884-5 in the band. Struck by Jenkins of Birmingham, it also has the date in Arabic in the Muslim calendar below, and on the clasp the star and crescent of the Ottoman empire on whose behalf - officially, at least - the British were fighting.

The two

Victorian campaign medals shown here were among my most prized artefacts while

I was writing Pharaoh, and appear as

illustrations in several editions of the novel. My 19th century

protagonist is a Royal Engineers officer in the 1884 campaign to relieve

General Gordon in Khartoum, and I was thrilled to discover a medal named to an

actual R.E. sapper who took part in the campaign. These two medals were awarded

to all British soldiers and sailors who saw active service in Egypt and Sudan

from 1882 to 1889, and were dated accordingly. The date of this example of the

Khedive’s Star, 1884-6, is consistent with the first medal, but because the

star was issued unnamed the recipient can never be known for certain. The

first medal, the Egypt Medal – one of the most beautiful of all British

campaign medals – is more informative, not only bearing the clasp ‘The Nile

1884-5’ but also the recipient’s name around the rim: 17818 Sapper M. Knight, 8

Company R.E., one of the sapper units present throughout the doomed attempt to

reach Gordon, and then in the months of fighting and eventual withdrawal from the

Sudan that followed.

The reverse of the two medals shown above, placed on a copy of the official history of the Royal Engineers in the campaign with the R.E. emblem in between. The first version of the Nile medal, created for the Anglo-French intervention in Egypt in 1882, had that year beneath the Sphinx, but once the decision was made to award the medal for subsequent campaigns the space was left blank and the campaign date put in the clasp instead. The obverse of the Khedive's Star shows his monogram surmounted by a crown.

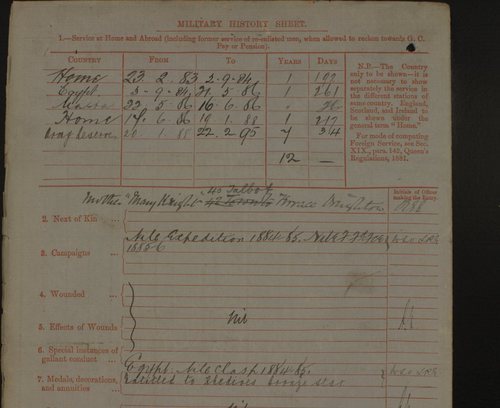

I managed to

find a copy of Mark Knight’s service record in the National Archives in London and

to match it to the official history of the Royal Engineers in the Nile

campaign, allowing a fascinating glimpse into his experiences. He was a bricklayer, aged 19 on his enlistment

in 1883, and signed up for the statutory twelve years. It’s possible that he

answered a call specifically for men with the right skills to join the company,

a new formation requiring ‘mechanics of all sorts’; during training they were

attached to civil railway works in Britain before being sent abroad. His

service papers confirm the award of the medals, and show that he was present in

the Sudan throughout the period covered in my novel. The company arrived in

Wadi Halfa from England in early October 1884, the start of an eighteen-month

deployment that saw them involved in the advance towards Khartoum, the retreat

from Sudan after the fall of Khartoum and then consolidation work along the

southern Egyptian border. On arrival they were set to work immediately repairing

the existing railway south along the Nile to Saras, and then extending it

further across the desert to Ambigol Wells and beyond. The official history reveals

the prodigious work involved: ‘the repair and maintenance of 33 and a half

miles of existing railway, the construction of nearly 54 miles of line through

barren country, the transport of 9,000 troops round the worst part of the

Second Cataract in ascending the Nile and round almost the whole of it in

descending that river, and the carriage of 40,000 tons of stores and munitions.’

Part of Sapper Mark Wright's army record, showing his service in Egypt and medal entitlement.

The work was

not without danger: one of the company

officers, Captain J.A. Ferrier, R.E., a veteran of the 1878-81 Afghan War, had

the distinction of commanding the fort at Ambigol Wells in early December 1885 during

one of the final actions of the campaign, when a force of some 700 dervishes

cut the railway line to north and south and surrounded the oasis, reputedly

shouting to Ferrier and his little garrison, ‘railway finish, telegraph finish,

you finish.’ In a version of Rorke’s Drift in the 1879 Zulu War – an action

also commanded by a Royal Engineer – Ferrier and his men defended their post

against fierce attacks until a relief column arrived, the first of several

actions over the final weeks of the campaign for which he was awarded the newly-created

Distinguished Service Order. Reading his citation, I realised that this was the

same Ferrier whose translation of a German book on the Franco-Prussian war is

in my library – there because its editor was my great-great grandfather,

Captain W.A. Gale, R.E., a colleague of Ferrier’s in the early 1890s when both were at the Royal

Engineers Institute at Chatham.

Whether or

not Mark Knight was present at Ambigol Wells is unknown, as his service record

doesn’t give that level of detail; but it seems likely that with his company he

would have seen persistent skirmishing with the Mahdist forces over those final months as they

toiled deep into the desert to the final station at Akasha, 87 miles from Wadi

Halfa and well within Mahdist territory. His record shows that he returned from

Egypt by way of Malta in June 1886, and then finished the remainder of his

five years' full-time service before going into the reserve, finally being

discharged in 1895 after having completed his twelve-year enlistment. He re-enlisted into the Royal Engineers for a year in 1900, when former soldiers

were re-employed for home service to replace regulars who had gone to the war

in South Africa. His papers show that he had returned to bricklaying after his

first enlistment, and probably he did so again after his second; there’s no

record of his subsequent life. As war in Europe loomed his medals must have

seemed a memento of a distant Victorian adventure, yet it was one whose

consequences - in fomenting fundamentalism in the Sudan and elsewhere, and renewing

calls for jihad - were to play out bitterly into the future.