David Gibbins's Blog, page 9

November 5, 2014

Video: a dive on the wreck of the SS Grip (1897), Cornwall, England

October 24, 2014

Free preview sampler of my novel PYRAMID

Click on this link to read a FREE PREVIEW SAMPLER of my latest novel PYRAMID:

https://www.headline.co.uk/assets/HeadlinePublishing/downloads/PYRAMID%20sampler.pdf

October 6, 2014

The extraordinary wartime voyage of M.V. Empire Elaine, 1943-4

The official history of the Clan Line during the Second World War, In Danger’s Hour by Gordon Holman (Hodder and Stoughton, 1948), contains many accounts of courage and loss among the Merchant Navy crews who provided a lifeline for Britain as well as support for Allied military operations in every theatre of the war. We are used to images of ships on Atlantic convoys, their crews enduring the constant threat of U-boat attack, but an oft-overlooked role of merchant seamen was the huge part they played in seaborne assaults and the dangers they faced there as well. Just what this involved is shown in the remarkable voyage of one of these ships as she reached the east coast of India in December 1944:

‘… in far-off Vizagapatam, Madras, Captain Coultas and his Engineer Officers were being relieved after voyaging for more than twenty months in M.V. Empire Elaine. During that time they had served Combined Operations at the Sicily landings, had been on special service in the Indian Ocean, had carried an 85-ton tug and many landing craft to ports in the Eastern war zone, had run through the monsoon, taken part in the South of France landings and had then returned for further service in Indian waters' (Holman, p 193-4).

Assault Ship M.V. Empire Elaine on the Clyde in early 1943 being repainted in preparation for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily (National Maritime Museum collection).

By the time Empire Elaine had reached Bombay a month earlier she had already clocked up 38,531 miles since leaving her home port of Glasgow in May 1943 and had sailed in 29 convoys, in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean, including the Bay of Bengal. This duration of this voyage alone makes her stand out, but there are two special reasons for my interest in this ship. The first is that during the 1980s I excavated a Roman shipwreck just south of Syracuse in Sicily, and often drove our dive boat over the sector where Empire Elaine had offloaded landing craft under fire during Operation Husky in July 1943. The second is that one of her officers during that voyage was my grandfather, Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins, who had joined her after her launch on the Clyde in the summer of 1942 and left her at Bombay in November 1944, his log book providing the mileage that I’ve cited here.

Captain Ernest Coultas, O.B.E., Lloyd's War Medal for Bravery at Sea, Master of M.V. Empire Elaine, 1942-44.

Empire Elaine was a 7,513 ton LSC (Landing Craft Carrier), and the Clan Line was chosen to manage her because of their heavy-lift expertise in transporting locomotives to India before the war. The photo above shows her in early 1943 following her first voyage, a 10,622 mile round-trip to South Africa via Gibraltar; her weather-damaged hull was in the process of being repainted in preparation for Operation Husky. You can see her armaments to fore and aft and above the bridge - a single 4-inch gun for use against surface vessels as well as a high-angle 12-pounder and six 20mm cannon against aircraft. The guns were under the overall command of a Merchant Navy gunnery officer, in this case my grandfather, and were manned by a mixture of Royal Artillery and Royal Marines gunners as well as trained merchant seamen for whom the Clan Line even had a special rank, ‘Seaman Gunner.’

Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins, Second Officer, M.V. Empire Elaine, 1942-44.

Her main crew comprised some fifteen British deck and engineer officers and about 80 ‘Lascar’ seamen, many of them recruited from coastal communities to the south of Bombay. The deck officers were all professional seamen and most had started their careers as Royal Naval Reserve cadets on HMS Conway or HMS Worcester, 19th century ship-of-the-line that served as schools for future officers of both the Merchant and the Royal Navies. Officers of the Clan Line, popularly known as the ‘Scots Navy’, wore braid very similar to that of the Royal Navy, as seen on the uniforms of the two officers illustrated on this page. Despite the meagre armaments of their ships, these men were more than willing to take the war to the enemy when the occasion allowed. Captain Coultas, a veteran of the First World War at sea, had himself been decorated earlier in the war for using his ship Clan Macbean in an attempt to ram a U-boat, saving the day ‘… by resolute handling of his unarmed ship, by brilliantly forestalling the enemy’s movements, and by courageously holding on his course, and so running into point blank gunfire from the submarine,’ and forcing the enemy to dive and allowing the ship to escape (The London Gazette, 19 March 1940).

Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, 9 July 1943: an assault convoy heading towards the British sector in heavy weather on the evening before the landings, very possibly KMS 18B including Empire Elaine (Lt F.G. Roper, R.N., Admiralty Official Collection, IWM A 18096).

On the Clyde, Empire Elaine joined assault convoy KMS 18B for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, leaving on 23 May 1943 and arriving at ‘Acid North’ sector off eastern Sicily on the night of 9-10 July. On the way the convoy had been struck by two U-boats off Algiers, resulting in the loss of three ships and many lives. At Acid North my grandfather recalled offloading landing craft under fire from shore, and also under the arc of 15-inch shells from the monitor HMS Erebus that shrieked over Empire Elaine towards the Italian coastal batteries. The sea was awash with the bodies of British airborne troops whose gliders had landed disastrously short in bad weather the night before, though the SAS had successfully overrun the Italian battery on Capo Murro di Porco, the rocky promontory immediately south of Syracuse – only a few hundred metres from the Roman wreck that my team excavated under the southern flank of the cape some forty years later, where we found rusted belts of Italian machine-gun ammunition on the seabed discarded over the cliffs after the Italians defences had been destroyed.

Operation Husky, invasion of Sicily, 10 July 1943: four miles south of Syracuse in 'Acid North' sector, an ammunition supply ship hit by enemy bombs burns close to the assault beaches. Landing craft can be seen on the shoreline below the smoke. Empire Elaine offloaded her landing craft at Acid North that morning and may well be one of the ships lying beyond the burning vessel in this photograph (Lt F.G. Roper, R.N., Admiralty Official Collection, IWM A 18091).

Nine months later Empire Elaine was on the other side of the world delivering landing craft for the war against the Japanese in Burma. Having sailed in convoy up the Bay of Bengal, she arrived at Chittagong, near the border with Burma - the main supply port for the British campaign against the Japanese - on 4 April 1944, at a time when the port was under air attack and the Japanese were threatening to envelop eastern Burma and break through into India. Directly to the north the Battle of Imphal was raging, and on that very day the Battle of Kohima began. These were attritional struggles equal to the American island battles in the Pacific, but they eventually saw British and Indian forces stem the Japanese advance and turn the tide against them. The landing craft carried by Empire Elaine were destined for seaborne assaults along the Arakan coast of Burma, and for assaults further east that would have taken place had the Japanese not surrendered after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

Enemy action was not the only hazard faced by Empire Elaine during her epic voyage: on 1 July 1944 she set out from Bombay for Aden as a one-ship convoy, escorted by HMIS Bombay, a corvette of the Royal Indian Navy, only to put back a week later ‘through stress of weather’ – she had run into the worst monsoon my grandfather was to experience in his forty years at sea. It was the second time he had been in a convoy that had been forced back by weather; in Clan Macnair in November 1941, in the thirty-seven ship convoy HX 162 from Halifax to Liverpool, his ship was one of many dispersed in a severe winter storm and forced to return and join later convoys and run the U-boat gauntlet again. In July 1944 after putting to sea from Bombay a second time Empire Elaine made it to Suez and then sailed across the Mediterranean for Operation Dragoon, the South of France landings, forming part of assault convoy SM 1C under US command and offloading landing craft close inshore under fire in Cavalière Bay. After that, the ship sailed across the Mediterranean and returned to the Indian Ocean, where she spent the remainder of the war transporting military supplies to eastern ports for the war against the Japanese.

Operation Dragoon, south of France, 15 August 1944: landing craft under British command after having been offloaded from assault ships, including Empire Elaine (photographer unknown).

My grandfather was not unusual among merchant seamen in having logged more than forty-eight months afloat in war zones, including many convoys during the worst months of the Battle of the Atlantic, and in having been at sea on the first day and the last day of the war. The Clan Line lost 30 of the 55 ships it managed during the war, and almost 700 officers and ratings. More than a quarter of British merchant seamen registered in 1939 were not alive in 1945 – a far higher death rate than any of the armed services. When I reflect on the crew of Empire Elaine and the many other merchant ships like her, I think of the motto of my grandfather’s and Captain Coultas' school, HMS Conway – ‘Quit ye like men, be strong.’ It was that ingrained sense of resolve that allowed these civilian sailors to make such a huge contribution to winning the war, and helped the survivors to endure its shadow for the remainder of their lives.

A note on sources

The UK National Archives has digitised its collection of Ship Movement Cards for the Second World War, allowing you to search for a merchant ship by name and then for a small fee download a scan of the card(s). These and the convoy records (ADM 136) are the primary documentation held by the National Archives on merchant ships during the war. The Ship Movement Cards do not necessarily indicate a ship’s involvement in a seaborne invasion, as assault landing zones did not count as ports-of-call; this information is more likely in the convoy records, where a convoy might be named as an assault convoy for an operation and the assault zone named as well. The convoy records are not available online but a database derived from them can be found at convoyweb.org, where you can search for ships by name and find its wartime movements. For ships sunk by U-boat action another site is Uboat.net. A full listing of the wartime convoys of Empire Elaine can also be found on Wikipedia in an article on the ship entitled MV John Lyras, her name after she had been bought by another shipping company following the war. As well as the book by Holman cited above, a full account of all ships managed by the Clan Line and further details of their wartime role can be found in Clan Line: Illustrated Fleet History, by John Clarkson, Roy Fenton and Archie Munro (Ships in Focus Publications, 2007), a superbly illustrated volume that must count as one of the most comprehensive fleet histories ever published for British mercantile shipping.

A large and fascinating collection of photographs taken by the official Royal Navy photographer of the British assault on south-east Sicily on 9-10 July 1943, including many images of merchant vessels involved, can be seen online in the Imperial War Museum collection website.

May 7, 2014

April 20, 2014

DESTROY CARTHAGE: UK paperback publication

The UK paperback publication of the first Total War Rome novel, DESTROY CARTHAGE.

April 8, 2014

March 1, 2014

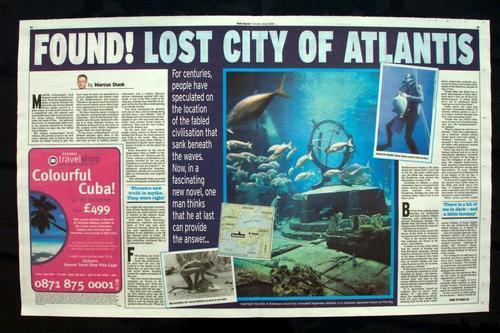

FOUND! Lost city of Atlantis

This two-page feature by Marcus Dunk on my first novel Atlantis appeared in The Daily Express on 23 July 2005. Since then Atlantis has sold well over a million copies and been published in thirty languages,

FOUND! LOST CITY OF ATLANTIS

For centuries, people have speculated on the location of the fabled civilization that sank beneath the waves. Now, in a fascinating new novel, one man thinks that he at last can provide the answer…

Marine archaeologist Jack Howard could not believe his eyes. From his Aquapod hundreds of metres beneath the Black Sea, the former Special Forces soldier peered at a giant statue of a bull at the entrance to a magnificent city, still majestic and intact 8,000 years after it was buried by the rising waters. Tutankhamun’s tomb, the walls of Troy … the hallowed discoveries of archaeology faded next to the greatest discovery of all time. Here before his eyes was the fabled city of Atlantis.

For marine archaeologist David Gibbins, this pivotal scene in his new novel, Atlantis, may be fiction but he insists it’s firmly rooted in fact. For more than 20 years, he specialized in ancient shipwrecks and sunken cities in the Mediterranean and Aegean. ‘Atlantis is the great unsolved mystery from ancient history, yet so often it has been approached as if it’s science fiction,’ says Canadian-born Gibbins. ‘All these theories about it being in the Atlantic, it being in Cuba, it being in Antarctica – they’re fun but they completely miss the point. Instead of seeking it in some fantastic location, we should be looking for it in the heart of the ancient world where civilization began. That’s far more exciting.’

In his novel, archaeologists led by Howard stumble upon clues to the location of Atlantis during excavations and race to find it, battling Islamic extremists and a sunken Russian nuclear submarine packed with warheads. A sort of Da Vinci Code of the deep sea, Atlantis may read like an airport thriller but the ideas underpinning it are deadly serious. ‘I’ve been fascinated by Atlantis ever since I was a kid in Canada doing my first dives,’ says Gibbins. ‘One of the things that I loved was how archaeologists in the 19th and early 20th centuries used ancient Greek myths to rediscover Troy and the lost civilizations of the Bronze Age. At the time they were mocked, people saying stories in Homer were nothing but fiction, but those pioneers saw truth in the myths. They were right. I felt the same about Atlantis. I wondered if maybe there wasn’t a kernel of truth in stories about its existence.’

First described by the Greek philosopher Plato in 360BC in two of his works, the Timaeus and the Critias, Atlantis is portrayed as an empire founded by the sea god Poseidon on a land mass the size of “Libya and Asia put together”. An advanced, conquering kingdom, said Plato, Atlantis met a nasty fate after it overreached and angered the gods. “But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea.”

Ever since then, historians, adventurers, explorers and multitudes of New Age nuts have advanced theories about its location and significance. It was Ireland, it was Australia, it was off the Spanish port of Cadiz, off Morocco, capital of a global pre-Ice Age civilization, terrestrial HQ of an intergalactic empire …

For Gibbins, the truth is more straightforward. His novel posits the idea that the lost city could be in the depths of the Black Sea, an area once lush and fertile before flooding caused the rapid evacuation of the area. ‘Two very recent discoveries underpin my theory in the novel,’ Gibbins says. ‘First, the startling evidence about sea level change after the Ice Age.’ The facts here are undisputed. Five million years ago, the Mediterranean dried out after being cut off from the Atlantic. What is now the Black Sea also greatly reduced in size. When the Mediterranean began to fill again during the “great melt” at the end of the Ice Age some 10,000 years ago, the Black Sea, separated by the Bosphorus, took another two thousand or so years to fill.

According to Gibbins, a great civilization came to its peak in the region during this period, until water crashed over the Bosphorus, flooding the land and creating today’s Black Sea in less than a year. But far from entirely disappearing, the inhabitants and their culture, religion, language and technology dispersed throughout Europe, the Middle East and North Africa – a diaspora that formed the basis for civilization as we know it.

Far-fetched as it may sound, this theory of the birth of civilization has become more widely accepted. ‘This is the second discovery that underpins my theory in the novel,’ says Gibbins. ‘A whole lot of new ideas about how the advent of farming and Indo-European language spread together around the ancient world at the dawn of history have been put forward, positing the idea that they all spread rapidly, and they came from one source. In my book, that source is Atlantis.’

If this theory is true, then all of us – genetically, culturally or in the language we speak – are decendants of Atlantis. But before we get carried away and take to the oceans, Gibbins is keen to point out that his theories about Atlantis are exactly that: theory. ‘It is speculation, based on evidence that we know,” says Gibbins. 'If – and when – more Black Sea expeditions go ahead, then I’m sure they would find amazing stuff. In the book I write about shipwrecks perfectly preserved in brine in the depths of the Black Sea, and part of that is true. Below 200m, the Black Sea is dead, with deposits of brine there from when it was cut off from the Mediterranean. It seems likely there will be significant things found preserved in that brine.’

Unlike others who claim that they have “irrefutable evidence” of Atlantis, Gibbins prefers to see it as a vague mythical idea that may have some grounding in fact. ‘People who use Plato’s reference as some sort of treasure map, they are like fundamentalists,’ he explains. ‘They’re taking the text far too literally – Plato was a philosopher, not a historian. Atlantis always meant much more than simply a drowned civilization. To the ancients it was a fascination with the fallen, with greatness doomed by arrogance and hubris.’

Every age has its own Atlantis fantasy, harking back to an era of unimagined splendour overshadowing all history. To the Nazis, it was the birthplace of the Ǖberman, the original Aryan homeland, spurring a demented search around the world for racially pure descendants. To some, Atlantis was a precursor of civilization lost in the depths of the Ice Age: a Garden of Eden, a Paradise Lost. ‘In the novel I suggest that even the ancient flood myths found in the Bible with Noah and in The Epic of Gilgamesh could have some connection with the Atlantis flood myth. It’s all fun speculation, but there’s some truth there.’

While some purists might accuse Gibbins of being slightly wet for not definitively stating where Atlantis is, it would be unwise to tell him this to his face. Like his fictional alter-ego, Jack Howard, Gibbins’ life can make him seem like a more adventurous cross between Indiana Jones and Jacques Cousteau – although he admits that Howard’s James Bond-like characteristics might be mere wishful thinking on the part of his creator.

‘I’ve worked for 20-odd years in this field, and there is quite a bit of me in Jack,’ laughs Gibbins, ‘and a little bit of fantasy. I’ve worked in central Asia, been involved with NATO science committees and had dealings with warlords.' Gibbins has also had more than his fair share of life-threatening experiences in the field. ‘I have had a couple of scary moments while working on deep wrecks,’ he says. ‘On one occasion I had an equipment malfunction and I ran out of air at 50 metres. It was a choice of either going for the surface – which I would not have made – or swimming for an emergency tank. I went for the tank, and made it just as I was blacking out. It is moments like that which really stay with you, and I’ve tried to give Jack some of those experiences.’

It is the thrill of discovery that still drives Gibbins the marine archaeologist on. ‘I have dived on a shipwreck off the coast of Turkey which dates from the fifth century BC, I have worked on submerged cities and I have helped to map the remains of the ancient harbour at Carthage. I get so thrilled at finding things. I once found a Roman doctor’s medical kit, complete with bronze scalpels. That feeling of recovering something loved and used – that’s amazing. I still love getting that Indiana Jones adrenaline kick.’

With his novel already sold for publication in 25 languages, a film version being mooted, and at least three more Jack Howard novels on the way, Gibbins is happy with being compared to The Da Vinci Code’s author Dan Brown – particularly if the financial rewards enable him to mount more expeditions. ‘I am delighted the books are being compared,’ he says. ‘I read Dan Brown’s after I finished mine, but I think that both books have a strong dose of fact running through them that is really stimulating to readers. If the book does as well as his, then I’ll use the money to finance more expeditions. Money is often a problem with doing fieldwork, so it would be a nice bonus.’

And if an Atlantis expedition were on the cards? Does he think the lost city will ever be found? ‘Let’s just say there’s little in fiction more incredible than the reality of our past,” he says. You simply have to look at the pyramids, imagine they didn’t exist and then try to convince people such things were possible five thousand years ago. They wouldn’t believe you. Amazing things are possible and anything could be discovered. We’ll just have to see.’

Marcus Dunk, 2005

February 27, 2014

TOTAL WAR ROME: the new cover for Destroy Carthage

Here's the brilliant new cover for the UK paperback edition of Destroy Carthage, published by Macmillan on 14 April.