David Gibbins's Blog, page 4

December 27, 2018

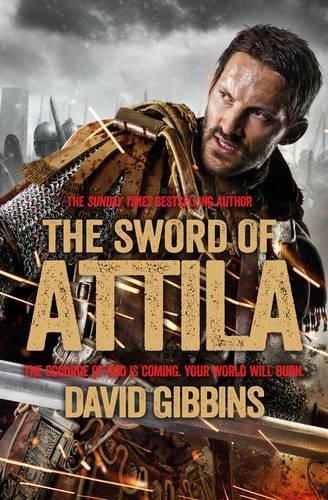

Hun Blitzkrieg: The Sword of Attila

My historical novel The Sword of Attila prompted thoughts about the similarity of modern ‘Blitzkrieg’ tactics to those of the Hun army of Attila in the 5th century AD. For more on the novel, go to my books page here.

The onslaught of Attila and the Huns against the western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD has come down to us as the very epitome of terror, as an unassailable force that swept all before it just like the Nazi blitzkrieg – the ‘lightning war’ – that put most of Europe under Hitler’s control soon after the outset of the Second World War. Any thought of tactical complexity by the Huns is subordinated by images such as the one reproduced here, from a popular history of France published in the 19th century, complete with trampled babies reminiscent of the exaggerated newspaper depictions of German atrocities in Belgium at the beginning of the First World War. There could be nothing exaggerated about the Nazi blitzkrieg of the Second World War, though images of that too were used to bring home the reality of the threat and galvanise opposition to it. Many fell before the onslaught, paralysed by terror; others gained strength by standing up to it, however belatedly. How much of this image of modern blitzkrieg can be applied to the Hun onslaught of the 5th century and the Roman response to it?

‘The Huns at the Battle of Chalons’ by Alphonse de Neuville (1836-85).

Certainly the rapidity of the Hun advance in the middle years of the 5th century bears all of the hallmarks of ‘blitzkrieg’, characterised by rapid movement, concentrated power and integrated military effort. It would be tempting to leave it at that – to ascribe the Hun success to an avalanche of action, and to the psychology of terror –were it not for a few precious accounts by ancient authors as well as archaeological finds that allow us to say something about tactical detail. Almost everything that has ever been written with any authority about Hun tactics derives from this passage by Ammianus Marcellinus, a Roman soldier in the late 4th century:

They are lightly equipped for swift motion, and unexpected in action; they purposely divide suddenly into scattered bands and attack, running about in disorder here and there, dealing terrific slaughter … you would not hesitate to call them the most terrible of all warriors, because they fight from a distance with missiles … then they gallop over the intervening spaces and fight hand to hand with swords, regardless of their own lives; and while the enemy are guarding against wounds from the sword-thrusts, they throw strips of cloth plaited into nooses over their opponents and so entangle them that they fetter their limbs …

The site of the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, the greatest battle ever fought by the Huns – and the last great battle of the western Roman Empire – has yet to be pinpointed conclusively, so battlefield archaeology cannot play a role. However, a number of Hun weapons have been discovered that give a sharp edge to Ammianus’ account. In 1979 near the monastery of Pannonhalma in Hungary a farm worker digging a new vineyard struck something in the sandy soil. He had discovered two great swords of the mid-5th century, possibly part of a sacrificial trove. They were straight, two-edged swords, over a metre in length, similar in size to the gauntlet swords of the Marathas in India of the 17th century and like those clearly designed for cavalry. Alongside the swords were the gold decorations that were all that remained from a composite wooden bow, an item of such richness that some scholars have even suggested that the trove might have been deposited by Attila himself.

These two weapons, the long sword and the bow, were the tools par excellence of the Hun warrior, and their prowess at using them from horseback goes a long way to explaining their success. Underlying it all was a physical strength hinted at in the only eyewitness description of Attila, by the Greek diplomat Priscus: ‘Short of stature, with a broad chest and a large head … a flat nose and a swarthy complexion, showing evidence of his origin.’ Whereas the Marathas in India used iron or brass gauntlets to strengthen their sword-arm, men of Attila’s physique would have had short, immensely powerful arms that allowed them to wield a long sword using the strength of their wrists alone, and to shoot a bow with accuracy and power even from a moving horse. It is possible, therefore, to suggest that the tactical strength of the Huns lay in the individual warrior himself – in his horse and horsemanship, in his weapons and his sheer physical strength, all of it fuelled by the adrenaline and battle-lust that came with the thundering speed of a cavalry charge.

The extent to which Attila’s onslaught represents tactical debate and decision-making can never be known. Even in the 20th century the concept of blitzkrieg as a coherent strategy was more a perception of the victims than the attacker, with the term itself first being used in British newspapers. Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that Attila - like Hitler - knew how a rapid onslaught could be boosted by the tactics of terror, epitomised by the shrieking siren of the Stuka dive bombers over Europe. Attila may have consciously exploited the Roman fear of the ‘other’, of the terrifying, larger-than-life warriors seen in the 19th century illustration; Attila had been classically educated and would have been well aware of the long-standing fear of barbarians from the east, of men like him, ‘swarthy of complexion … showing evidence of his origin.’ But what both Attila and the Nazis could only learn through experience was the one great weakness of blitzkrieg, that it depended for momentum on the rapid collapse of an enemy and faltered once an enemy resisted. This was what Attila discovered to his cost when the Roman forces under Aetius met him in set-piece battle at the Catalaunian Plains, just as Hitler was to discover when the British refused to bow to the Nazi air onslaught and the threat of invasion and instead stood their ground.

This article first appeared in the Pan Macmillan blog here.

November 4, 2018

3-D photogrammetry on the wreck of the Schiedam (1684)

In my novel INQUISITION, Jack and Costas make an astonishing discovery on the wreck of the Schiedam off Cornwall in England. The Schiedam is a real wreck - one of the most fascinating I’ve ever dived on, with a cargo of guns and other objects being brought back from the failed English colony of Tangier in North Africa in 1684. For many years the wreck had been buried in sand, but in 2016 we rediscovered it and since then my colleague Mark Milburn and I have been going out to the site when the weather allows to photograph, video and record as much as we can. In early October this year a huge storm swept the sand from the site again, and after the sea had settled I was able to get out on the wreck over several days and do some fabulous dives in the best visibility I have ever experienced on the site.

These were exactly the conditions I needed to try some photogrammetry of the wreck, and the results are the two models below - one of a two-metre long cannon, the other of a section of worn ship’s timber with a slab of marble beside it. Both of these involved hundreds of overlapping photographs and a lot of time spend white-balancing and sharpening each photo. But it was undoubtedly worth it - 3-D images like this are very evocative and more meaningful from an archaeological viewpoint than the measured and drawn plans that used to occupy huge amount of time underwater.

Click on the images to go to the models on Sketchfab, and zoom in to see close-up detail (for example, the carpentry on the right side of the timber).

October 23, 2017

New England ancestors, 1621-1700

Mayflower II, built in 1955-6 and currently under restoration in Mystic, Connecticut, prior to its planned return to Plymouth in time for the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the original Mayflower in 1620. The Fortune, which brought Thomas Prence and 33 other settlers to Plymouth Colony in the following year, was only one-third the size of this ship.

This pedigree chart was published in a 1942 book entitled Personal Religion by Douglas Clyde Macintosh, a Professor of Theology and the Philosophy of Religion at Yale University who used his own family history in England and colonial America to illustrate the association between non-conformism and what he termed ‘personal religion’. He was the grandson of Cotton Mather Everett, at the bottom of the chart, a ship’s physician with the East India Company who settled in 1832 in Canada. The Everetts were a prosperous family of clothiers in Heytesbury, Wiltshire, where their line can be traced back to the 16th century. One of Cotton Mather Everett’s brothers, Edward Jackson Everett, had a daughter Octavia, who married John George Gibbins – my great-great grandparents. This pedigree chart is therefore also my own.

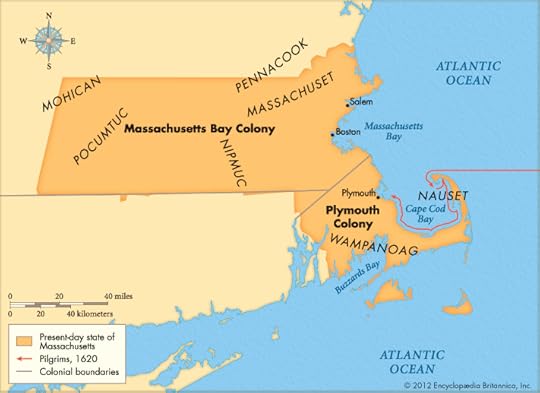

What particularly interested Macintosh was his descent from John Cotton (1585-1652), one of the pre-eminent theologians of early New England. The son of a Derby lawyer, John Cotton studied at Trinity and Emmanuel Colleges, Cambridge, before becoming Priest of St Botolph’s Church in Boston, Lincolnshire, where he advocated dispensing with the liturgy and vestments of the Anglican service – views similar to those of the Puritans who left on the Mayflower in 1620 to found Plymouth Colony. Cotton’s teachings brought him into increasing conflict with the Anglican establishment, and he and his wife Sarah left for the Massachusetts Bay Colony on board the Griffin in 1633. Once in Boston (named in 1630 by several of his congregation from Boston, Lincolnshire, who had preceded him there), he became minister of the church and played a prominent role in debates about the nature and governance of the church in the colony, publishing many books and pamphlets up to the time of his death in 1652.

One of numerous works by John Cotton, this one published shortly after his death.

John Cotton founded the Boston Latin School in 1635, and a year later was one of the founders of the college that would become Harvard University. His son Seaborn Cotton (1633-1686) – born during the voyage of the Griffin to America, hence his name – attended Harvard, as did Seaborn’s son Roland (1674-1725); Seaborn became minister of Hampton, New Hampshire. Seaborn’s sister Mariah married Increase Mather, President of Harvard from 1692 to 1701 and father of Cotton Mather, best-known for his involvement in the Salem Witch Trials but later a Fellow of the Royal Society. According to one account, ‘… it is believed that the Cotton family in its various branches has produced more men of the clerical profession than any other in New England.’ Bucking this trend, Seaborn’s son Roland left America in 1700 to study medicine in England and Holland, and settled in Warminster, Wiltshire, where he married and worked as a physician; he was the last of my ancestors in that line to have lived in America.

In Personal Religion, Douglas Clyde Macintosh’s interest in his colonial ancestors was largely restricted to John Cotton and his theological journey, and to the connection that Macintosh could find between that and the non-conformist beliefs of the Everett family in the 18th and 19th centuries. However, his ancestry was more diversely rooted in colonial America than this suggests. Seaborn Cotton’s wife Prudence, born in Ipswich, Massachusetts Bay Colony, in 1637, was the daughter of Jonathan Wade and his wife Susannah (née Prence), who had arrived from England on the 1632 voyage of the Lyon. Jonathan was a merchant who became a Representative to the General Court of Massachusetts, served as a Militia Colonel in King Phillip's War against the Wampanoag, came to own at least 640 acres of land near Ipswich and at the time of his death in 1684 had an estate valued at nearly 8,000 pounds, making him one of the wealthiest men in New England in the 17th century. Prudence was one of four daughters and three sons, all of whom married into prominent colonial families and whose lives and descendants are well-documented in sources from the period.

Plimoth Plantation, the living history museum at Plymouth, Massachusetts, that attempts to replicate the colony as it would have been about the time that Thomas Prence arrived in 1621.

An even earlier arrival was Susannah Wade’s brother Thomas Prence, one of 34 passengers to land at Plymouth in November 1621 from the Fortune – the second ship to be sent out with colonists to Plymouth, following the Mayflower the year before. Aged only twenty, he was one of the ‘lusty young men, and many of them wild enough’ who at first dismayed the surviving colonists, but then provided them with much-needed labour. Prence did well for himself, marrying the daughter of a Mayflower pilgrim and in 1634 becoming Governor of Plymouth Colony.

Even by that date, when the colony had become well-established, its population was probably fewer than 400; when Thomas arrived in 1621 it had been a mere 46 people. The Fortune itself was barely a seagoing ship, at 55 tons being less than a third the tonnage of the Mayflower. It was the fortitude needed to undertake those voyages and thrive in the conditions of the new colonies that makes the lives of these early settlers so fascinating, whether or not their main motivation was to discover a ‘personal religion’.

A map of early New England showing the relationship between Plymouth Colony, founded in 1620, and Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded a decade later and focused on Boston (source: Encyclopedia Britannica).

July 19, 2017

Historical fiction, ancestry and artefacts

Click on the image below for a blog I've just written for the H is for History website on historical fiction in my novels.

June 24, 2017

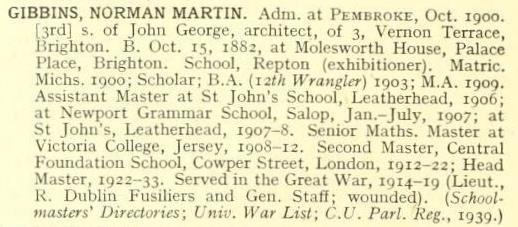

First World War Centenary: Lieutenant Norman Martin Gibbins and chess in the trenches, 1917

This 'thing of beauty born in suffering' was devised by my great-great uncle Lieutenant Norman Gibbins of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers in 1917. He had been severely wounded by a shell near Loos in June 1916, and after a year spent recuperating was back in France in June 1917. He would appear to have created this chess problem while recovering from a fall from a horse. Fortunately, he was evacuated sick to England shortly before the start of the Third Battle of Ypres, in which his battalion was virtually annihilated. His mathematical talents were then put to better use as a Cypher Officer in the War Office in London, and with the British Army in Italy.

'Headmaster Gibbins, mathematics master Evans, and Dan Pedoe at the Central Foundation Boys School in London, 1927.' On the cover of The College Mathematics Journal 29.3 (1988).

Norman had been a Maths Wrangler at Cambridge - achieving a First Class degree - specialising in geometry, and had taught maths before the war. Afterwards he became Headmaster of Central Foundation School, London, where his pupils included many talented boys from recently emigrated East European Jewish families. The photograph shows Norman, left, and on the right Daniel Pedoe, later a distinguished mathematician and geometer. Norman published many articles on geometry and chess through his life, several of them with another of his proteges at Central Foundation School, Jacob Bronowski. Norman is probably best remembered for his 1944 article 'Chess in three and four dimensions' in The Mathematical Gazette. He also published a booklet on Fairy Chess Problems, the 'Fairy' referring to a particularly challenging form of chess in which the rules, pieces or board can be changed.

Norman was the inspiration for a character in my novel The Last Gospel. See also my earlier blog on chess and trench warfare here.

Sources

Lieutenant Norman Martin Gibbins, Royal Dublin Fusiliers: Officers' Services. UK National Archives, WO 339/47801

War diaries, 8th and 1st Battalions Royal Dublin Fusiliers. UK National Archives (also available at Ancestry)

Gibbins, N.M., 1911-1952, a total of 76 articles in The Mathematical Gazette

Gibbins, N.M. and Bronowski, J., 1927-48, A total of six chess problems in British Chess Monthly

Gibbins, N.M., 1947. Fairy Chess Problems. Stroud Publishing

Pedoe, Daniel, 1998. In love with geometry. The College Mathematics Journal, 29.3: 170-88

May 11, 2017

Wrecks and wrecking at Gunwalloe: fact and fiction

Click on the image below to read a piece I've written for the National Trust's Natural Lizard blog, devoted to the natural history and history of the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall, England. My blog is about the influence of my shipwreck discoveries in these waters on my novels, and the fine line between reality and imagination in creating archaeological fiction.

The wreck of HMS Primrose, Cornwall, England, 22 January 1809

A plan dated 1 December 1802 showing the framing disposition of 72 vessels of the Cruizer class lauched between 1803 and 1809, including HMS Primrose (National Maritime Museum ZAZ 4140).

Last July I dived with a team from Atlantic Scuba on the wreck of HMS Primrose, a Royal Navy sloop that struck the Manacles rocks east of Falmouth during a winter gale in 1809. Of some 126 crew and passengers aboard, only one person survived. The wreck has been extensively salvaged by divers, and today only a few artefacts are visible among rocky fissures and gullies at about 12 to 15 metres depth, under dense growths of kelp. Our dives were carried out in conjunction with an evaluation of the site for Historic England by Wessex Archaeology, and in this video by Jeff Goodman of Scubaverse you can see footage taken during our dives. The photos by Mark Milburn below show cannonballs heavily accreted to the seabed, and illustrate the difficulty of identifying wreck material at this site (click to enlarge).

History

HMS Primrose was a Cruizer-class brig-sloop built at Fowey, Cornwall, by Robert Nicholls, and launched on 5 August 1807. She measured 100 feet 6 inches in length, 30 feet six inches in beam and 384 tons burthen, had a crew of 121 and was armed with sixteen 32-pounder carronades and two 6-pounder bow-guns. No depictions are known of Primrose herself, but the Admiralty Collection in the National Maritime Museum contains a number of plans of the Cruizer-class including the one shown at the top of this blog of vessels of Primrose’s batch, ordered by Admiral Barham’s Board and launched in 1806-7.

The Cruizer-class were the most numerous Royal Navy vessel built during the Napoleonic Wars, with 110 vessels being built to the original 1797 design. At a time when the Royal Navy was suffering severe manpower shortages, the Cruizer-class was attractive because the brig-rig – with only two masts, the fore and the main, by contrast with the three masts of a ship-rig – required fewer men to manage, as did the carronades compared to conventional cannon. These features were also the ships’ main drawbacks: the carronades were devastating at close quarters, equalling the firepower of a frigate, but with their shorter range they left the ships vulnerable to cannon fire at greater distances, and whereas a ship-rigged vessel could survive the destruction of one mast and still manoeuvre adequately, this was not usually the case with a brig.

This depiction of HMS Recruit, another one of the batch of 17 Cruizer-class brig-sloops built to the Barham's Board design in 1806-7, gives an excellent impression of the appearance of HMS Primrose. The two-mast brig-rig can clearly be seen, as well as the portholes for the carronades. The caption reads 'Intrepid behaviour of Captn Charles Napier, in HM 18 gun Brig Recruit for which he was appointed to the D'Haupoult. The 74 now pouring a broadside into her. April 15 1809.' Recruit survived this action, and was sold in 1822 (etching, George W. Terry and George Greatbach, National Maritime Museum PAD5779)

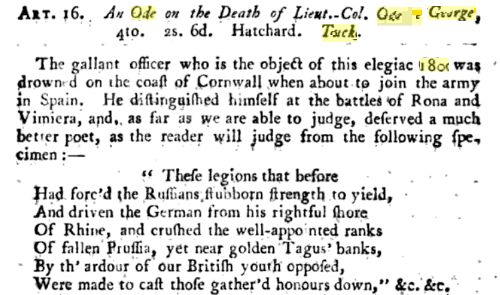

As with other wrecks of this period, the loss of HMS Primrose occasioned a literary epithet - in this case an ode on the unfortunate Colonel Tucker, who, as the anonymous author of this review in The British Critic opined, 'deserved a much better poet.'

Under Commander James Mein, Primrose sailed for Spain on 3 February 1807, and took part in an action on 14-18 May in the Tagus river in which she rescued the crew of another brig sunk by a shore battery. She sailed again for Spain as a convoy escort in early 1809, leaving Portsmouth on 5 January and was wrecked in a snowstorm against Mistral Rock in the Manacles at about 5 am on 22 January. ‘She struck on the outer rock of the Manacles, drove in on the shallow ground and sank.’ Despite the efforts of the Manacles Signal Post officer and a boat manned by six local fishermen, none of those on board could be saved except for a seventeen-year old boy, John Meaghan. The newspapers reported on the following day that ‘His majesty’s brigs Swallow and Sparrowhawk, sailed last night to endeavour to save what remained of the crew and stores of the unfortunate Primrose, and returned this evening, nothing remaining above water; the Primrose’s mast heads are just above the high water mark; the poor little boy, who is the only survivor, was taken off from the royal mast head.’

Among the six passengers were two brothers, Lieutenant Colonel George Tucker and Captain Nathaniel Tucker, two of five brothers serving in the army at that time, and both returning for service in Spain. On the same night another ship was lost on the Manacles, the Dispatch, containing a contingent of the 7th Dragoons returning from Spain. Many bodies from both wrecks washed up on shore, and more than a hundred were buried in St Keverne churchyard where the memorial stones can be seen today.

Other artefacts

A number of artefacts attributed to this wreck are on display in one cabinet in the Charlestown Shipwreck and Heritage Centre in Cornwall. The caption states that ‘The items in this case have been recovered from the wreck site in the last few years with the help of the Northampton Sub-Aqua Club, and they largely relate to the two 32 pound carronades displayed outside. The smaller items here were either concreted to the guns or formed part of the carriages, which, being wood, are still undergoing conservation.’ It seems likely that this display was created at least thirty years ago, as the main period of salvage by the Northampton club was in the late 1970s. At some point in recent years the two carronades disappeared from outside the museum, and their whereabouts now are unknown.

The cabinet contains finds from other wrecks, in the vertical display above the caption and on the lower shelf. Among the unlabelled artefacts on the two shelves that would appear to be associated with the Primrose, those that may be of questionable attribution are two intact onion bottles, a form of bottle shape that would normally be dated to the 17th or early 18th century. Of the other artefacts, a small copper-alloy gun found by diver Reg Dunton at or near the site in 1963 may well be from the wreck - it may be a boat gun - but more detailed study is needed to establish whether it can be independently dated and its place of manufacture established ( the caption identifies it as of Danish origin, but the basis for that identification is unknown).

Artefacts from Primrose are displayed in the lower part of the upper case and the top shelf of the lower cabinet (Charlestown Shipwreck and Heritage Centre). Click to enlarge; see below for close-up views.

In the absence of any published report on the salvage work carried out on this wreck, the comment in the display cabinet caption about the gun carriages and artefacts begin found in concretion is evidence for site formation and preservation. During my dive on the site I saw only a few places where extensive burial of artefacts in stable sediments might be expected; most of the site was a highly variegated seabed of exposed rock, with much accretion. The rapid formation of ferrous concretion from the iron carronades over the gun carriages, preserving both the wood of the carriages and other artefacts nearby, including organic materials, may explain the survival of materials in such an exposed site. Along with contemporary news reports that the ship was resting upright on the seabed, the mast-tops exposed above the surface, this suggests that the wreck before salvage may not only have retained a wide range of artefacts preserved in concretion, but also a degree of distributional coherence that may have reflecting the dimensions and layout of the ship. As with all such wrecks that have been salvaged without recording, it is a pity that this information is lost.

The artefacts below, from left to right in the upper part of the display cabinet, include a pewter plate, copper or copper-alloy pins, a name plate for a 32 pound carronade, two onion bottles (one still stoppered, and both of questionable association with this wreck), a lead-lined copper bowl (perhaps for lading gunpowder), wooden pulley and sheave blocks, an intact leather shoe and another bottle. Click to enlarge.

The gallery below, left to right in the lower cabinet, shows lead shot for pistol and musket as well as grape-shot, weights, cast-iron slewing wheels for the carronades, metre-long copper or copper-alloy hull-fastening pins, a small copper-alloy gun with a three-inch bore, a photo of Reg Dunton with the gun in 1963, pieces of breeching rope for the carronades and a wooden tompion with its spunyarn plug found in the muzzle of a loaded carronade. Click to enlarge.

These photos show a carronade being raised from the wreck of Primrose, perhaps in the late 1970s; a carronade and cannonballs after cleaning; two carronades said to have been from the wreck at the Charlestown Shipwreck and Heritage Centre (now missing); and a cannonball said to be from the wreck.

June 26, 2016

Fricourt New Cemetery, Somme 1916

In late May this year I visited the Great War battlefields of northern France on the trail of my grandfather Tom Verrinder, who served with his brother Edgar in the 9th Lancers on the Western Front from 1916 to 1918. I began my visit where my grandfather had his 'initiation into warfare', as he termed it, on the Somme battlefields of 1916. On the first day of the battle, on 1 July, his regiment had been poised with the rest of the cavalry to follow the infantry through the German lines, but when the breakthrough never happened the cavalry were dismounted and used for battlefield clearance - to find wounded men and to bring together and bury the bodies of the fallen.

In a previous blog I wrote about the work of the 9th Lancers dismounted party - ghoulishly termed a 'vulture party' by one officer - in front of Fricourt, where the 10th Battalion of the West Yorkshire Regiment suffered the highest casualty rate of any British infantry battalion on that morning. 159 of those men were buried together where they fell, in four mass-graves in the former no-man's land. After the war those burials became the site of Fricourt New Cemetery, which also contains men from the 7th East Yorkshires who died here on the first day of the battle.

As I walked out of Fricourt on the first morning of my visit, into no-man's land and towards the cemetery, I was struck by the beauty and tranquillity of the place - not only the cemetery itself, but also the rolling chalk grasslands visible off into the distance, dotted with the woods that were to become such terrible places as the fighting progressed. Taking in the view it was hard to imagine the enormity of the death and destruction that took place here in 1916, but my archaeologist's eye was drawn to the plough soil where the evidence is still there in abundance - the chalk spoil from the trenches, and huge quantities of rusting shell fragments and other debris that litter the fields for miles around. You can see a photograph of some of these artefacts below.

An overlay of the 25 April 1916 British 1:20,000 trench map 62D.NE2 on a satellite image of Fricourt and the fields to the west. In the centre is no-man's land as it existed before 1 July 1916, with the British front line in blue to the left and the German in red to the right. The red blotches where the lines are closest, between the words Red Cottage and Fricourt, are the 'Tamour mines', the craters of which are still visible in the woodland that covers that part of no-man's land today. Fricourt New Cemetery is in no-man's land to the left of the letter R in Red Cottage; the point where I took the photo holding the artefacts looking back towards the cemetery is at the top left of this image where the lane crosses the continuation of the British front line, not shown here but marked on the adjacent trench map (from the National Library of Scotland First World War trench maps website.)

Fricourt New Cemetery, looking south.

The view south from the ridge above Fricourt (at the top of the map in the first image) towards Fricourt New Cemetery, with the Tamour mines area to the left and the village of Fricourt out sight just beyond that. This view encompasses no-man's land from the British front line, to the right, to the German line, to the left, just within the Tamour mines wood. Walking heavily laden down this slope soon after 7.30 am on 1 July, the 10th West Yorks were met by fire from a single German machine gun positioned in the Tamour area. Because this had been a quiet sector before the battle, no-man's land was not yet pockmarked by shell holes and the men had nowhere to take cover. By the end of the day, only 21 men of the battalion had made it back to the British line; 740 had become casualties. Most of the men who were killed died in this field without even having seen their enemy.

Battlefield debris picked up from no-man's land, just outside the British front line looking towards Fricourt New Cemetery (above my forefinger), with the Tamour mines area in the wood beyond, the Bois Francais on the far ridge beyond that and the village of Fricourt to the left. The shell fragments are likely to be from the German barrage that opened up on no-man's land during the morning of 1 July, adding to the carnage among wounded men who had been hit by machine gun fire during the initial assault. The broken British .303 cartridge (easily distinguished from German cartridges by its rimmed base) and the German 7.92 bullet, found where I am standing, are particularly poignant finds - the machine gun in Fricourt would have been aimed to hit men at waist height as they were advancing down the slope, with spent bullets ploughing into the ground about where I am standing.

Fricourt New Cemetery, looking north-west up the slope towards the British line. The gravestones in the front row are of men of the 7th East Yorkshire Regiment; those behind are of the 10th West Yorks. All of these men died at or near this spot on 1 July 1916. The previous two photos were taken from the ridge in the background looking in this direction.

April 9, 2016

Diving Lock 21: a submerged Victorian canal lock on the St Lawrence River, Canada

My brother Alan and I had the exciting experience last autumn of diving in the St Lawrence River on a submerged canal lock dating from the 19th century. What had once been an extensive canal system, built to allow ships to pass between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes, now lies deep beneath the floodwaters of a hydroelectric dam. As Alan’s film shows, the lock that we explored – Lock 21 of the Cornwall Canal – was a gloomy, forbidding place, swept by strong currents that made it a challenge to dive. Nevertheless, discovering the lock was highly rewarding and gave us an insight into a remarkable achievement of Victorian engineering, one that helped to shape Canada’s early history.

This map of the 1950s St Lawrence Seaway project illustrates the impact that improved navigation along the river was expected to have, allowing direct transport for large ships between the Atlantic and the Great Lakes. The original Cornwall Canal lies in the middle of the Seaway, mid-way between Montreal and Kingston.

On that same trip we filmed another amazing site near the entrance to the St Lawrence River on Lake Ontario, the wreck of the War of 1812 frigate HMS Prince Regent. The story of that ship and the other large warships built at Kingston in 1813-14 is intimately linked with the development of the canal. The British needed large warships on Lake Ontario to counter the American threat, with frigates and ships-of-the-line on the stocks at the US Navy yard at Sackets Harbour. But there was no way of bringing large warships up the St Lawrence from the Atlantic – there were too many areas of treacherous shallows on the river, including the Long Sault rapids near the town of Cornwall. The only option was, like the Americans, to build the ships on the lake itself, but even that task involved formidable transport challenges, with heavy materials such as guns and iron ballast having to be hauled overland to Kingston from the downriver ports of Quebec and Montreal. The completion of the two frigates and the ship-of-the-line launched at Kingston in 1814 was an astonishing achievement, but not one to provide a model for future emergencies.

A photograph of Lock 21 looking east, thought to have been taken about 1904. The buildings to the left are on the site of the present information pavilion, with the water level today being about a metre higher than the top of the embankment. Our dive in the video took us down the slope to the railing at the top of the weir, then over the railing to the bottom of the canal, through the sluice gates (underwater in this photo) and out the other side (photographer unknown).

A view of Lock 21 looking in the opposite direction to the photo above, with the US bank of the St Lawrence in the background. We're standing close to the site of the buildings about the embankment seen in the 1904 photo. The concrete block in the foreground marks the eastern end of the lock, with the block just visible about a hundred metres upstream marking the western end at the weir and the entry point for divers.

The first canal system in Canada, the Rideau Canal between Kingston and Ottawa, was itself a military conception, designed to provide a line of communication and transport in the event of war and planned by the Royal Engineers. By the time the Cornwall Canal was built, in 1834-42, the threat of war had receded, and the overwhelming need was to provide better transport and trade between the Atlantic and Upper Canada. The advent of steamships hugely increased the rate of traffic, and soon the original nine-foot depth of the canal proved inadequate. From 1876 to 1904 the entire eleven and a half mile length was deepened and widened, with Lock 21, the first lock at the upper end of the canal, being completed in 1886, allowing ships through with a draft of 14 feet and up to 245 feet in length, with cargoes of about 2,500 tons.

The vital importance of the the canal throughout this period and into the 20th century is shown by the attention paid to it in the Public Works proceedings of Parliament, and in many photographs showing ships passing through the locks in both directions. The following four photos of Lock 21, all thought to have been taken in the early 1950s, show 'lakers' and 'salties', the former the distinctive barge-like boats of the Great Lakes and the latter small ocean-going freighters (photographers, from left: Dan McCormick; Jim Kidd; Dan McCormick; unknown).

A plan of Lock 21 for divers on display in the information pavilion at the site. For our dive seen in the video we followed the rope down to the weir, went through the sluice gates and came up the other side.(plan: N. Baets).

The final transformation of Lock 21 took place over a few days in July 1958, when the canal and many surrounding villages were inundated to create the head pond for a hydroelectric dam near Cornwall as well as to raise the river level for the new St Lawrence Seaway. The river current, such an impediment to early shippers, was thus put to good effect as an electricity generator, and the construction of the wider channels of the St Lawrence Seaway allowed larger ocean-going vessels to get through. The Lost Villages have also become a dive attraction, and a number of the pioneer houses that were saved from the flooding can be seen today at Upper Canada Village.

We easily found the entry point to Lock 21 off the Long Sault Parkway, as the site marked by a plaque and an information pavilion set up for divers. After kitting up we waded out along the top of the former canal embankment and found the guide rope for divers that led down some twelve metres to the railing above the weir. The rope proved essential against the current, which was running at some three knots over the weir – impossible to swim against, and strong enough to pull my pony bottle regulator out of its retainer beneath my neck and leave it dangling behind, as you can see in the film. Once we had made our way over the lip of the weir and dropped to the floor of the canal, a little over 18 metres deep, we were out of the main force of the current and able to appreciate the massive structure in front of us. The most striking features were the sluice channels of the weir, and Alan filmed me while I rocketed through one of them with the current and then clawed my way back in order to allow him to film me doing it again from another angle. By then the exertion had depleted our air, and once he had followed me through we made our way back up the slope against the current towards the surface. You can see all of this in Alan’s excellent video.

April 6, 2016

Diving the wreck of HMS Prince Regent (1814), Kingston, Ontario, Canada

One of my most memorable recent dives was last October in only a few metres of water at the head of Deadman Bay, near Kingston at the eastern extremity of Lake Ontario in Canada. My brother Alan and I had gone in search of HMS Prince Regent, a British frigate of the War of 1812 that had been abandoned in a backwater and lain undisturbed for over a century and a half. What we saw when we found the wreck far exceeded our expectations. We had known that a large part of the lower hull remained intact, preserved in the fresh, cold waters of the lake, but we had little idea of the haunting, eerie image that would be caused by the weed and algae growth that shrouded the wreck. Fortunately Alan had his video camera with him, and was able to capture the atmosphere of the site in the film you can see opposite.

An 1817 aquatint of the British squadron at anchor off Oswego on 6 May 1814, based on a drawing by a Royal Marines officer present at the action, Captain William Steele. The frigate to the right, flying the broad pennant of Commodore Sir James Yeo, is HMS Prince Regent, flagship of the squadron. The boats being rowed ashore are taking Royal Marines, sailors and soldiers to the assault of the fort atop the distinctive jutting promontory, visible amidst the smoke from the bombardment (National Archives of Canada).

The story of HMS Prince Regent and the two other large warships launched at Kingston during the final year of the war, HMS Princess Charlotte and HMS St Lawrence, is a fascinating one for many reasons. Although the ships only saw limited action – in the case of HMS St Lawrence, none at all – they were one side of the arms race that developed between the British and the Americans on Lake Ontario during the war, with the Royal Navy Dockyard at Kingston competing with the American yard at Sackets Harbour to build the most powerful ships. Without the extraordinary efforts of the Kingston shipwrights, completing ships in near-record time, the race could have been lost and the war gone badly against the British. The problem was that large warships on the Atlantic could not be brought down the St Lawrence River to the lake, as the rapids above Montreal had not yet been bypassed by canals; the largest warships on the lake before 1812 were sloops and brigs. The ships launched at Kingston in 1814 were to be the only British warships of their size to be built and operated exclusively on fresh water, with design features uniquely adapted to conditions on the lake and reflecting the enormous pressure to complete the vessels in time to act as a deterrence.

A draught and profile drawing of HMS Prince Regent made by Royal Navy surveyor Thomas Strickland in 1815. The V-shaped deadrise of the frames from the keel was even more pronounced on the Princess Charlotte (National Maritime Museum, Greenwich).

After the Royal Navy commander on Lake Ontario, Commodore Sir Thomas Yeo, ordered the construction of frigates at Kingston, the yard quickly expanded in readiness. White oak was felled, artificers were brought from the yards of Lower Canada and from England, and old ships at Quebec allocated for the purpose were stripped of ballast, guns, canvas and other material to be taken past the rapids to Kingston for the new vessels. By late November 1813, only a few months into construction, the Governor-General was informed that Prince Regent promised to be 'as fine and formidable a Frigate as any sailing on the Atlantic.' After what must have been an extraordinary winter of activity at the shipyard, both Prince Regent and the smaller Princess Charlotte were launched on 14 April, as soon as the lake ice had melted. Within three weeks they had been crewed, fitted out and trialled, Prince Regent proving to sail 'remarkably well.'

To the casual observer there would have been little to distinguish these ships from the seagoing frigates of the Royal Navy. They were in fact of heavier construction than had been the norm, with thicker timbers and closer-fitting frames, the British having learnt the lesson of earlier frigate actions in the Atlantic where heavier-built American vessels had withstood shot better than their British opponents. The most striking difference lay below the waterline; because the lake ships had no need to carry large quantities of drinking water - and thus had no need for a capacious hold - they could be sharper in profile, with a steeper frame 'deadrise'. This feature and a shallower draft made them fast and weatherly, and without the weight of water more guns could be carried. Other features reflected the expediency of construction. There had been no time to season the oak properly, so the wood was green, more vulnerable to rot. Shorter lengths of timber were used than was normally the case, scarfed and bolted together, and there had been no compass timbers or 'grown knees' from which curved elements were normally cut. Nevertheless, with a crew of 550, and armed with thirty twenty-four pounders and twenty-eight carronades - twenty of them 32 pounders and eight massive 68 pounders – she was well up to the task at hand, and with these two ships and several large brigs Sir Thomas Yeo had a frigate squadron as formidable as any that were ranging the high seas in the final years of the Napoleonic Wars.

War Service and aftermath

With the 1814 Spring sailing season underway, Sir James Yeo was determined use his new ships to attack Sackets Harbour, but the Governor-General Sir James Prevost refused to allocate the troops required to mount an assault in strength. Instead, Yeo turned his attention to the less heavily defended Fort Oswego, a staging post from New York via the Hudson and Oswego rivers where it was believed that guns destined for the new American frigates lay in storage. By attacking the fort and taking the guns, Yeo planned to secure advantage over the Americans for the 1814 season. On 3 May, he left Kingston with HMS Prince Regent, HMS Princess Charlotte and six sloops and brigs, arriving off Oswega two days later. After a delay caused by the weather he landed his assault force of Royal Marines, a Royal Navy landing party and soldiers of the Glengarry Light Infantry and the Regiment de Watteville, over a thousand men altogether. Much of their powder was soaked in the landing, so they attacked at the point of the bayonet. After a bombardment from the frigates and the smaller vessels, they advanced up the slope and took the fort at a cost of some 80 casualties, inflicting some 60 casualties on the Americans and capturing some 30 more.

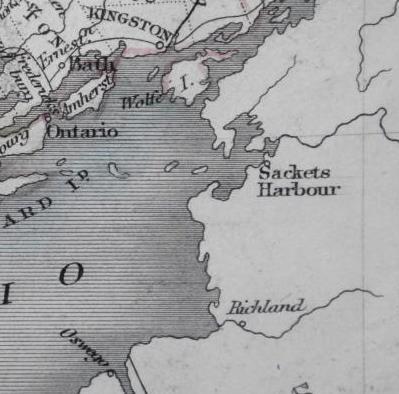

A 19th century map showing the eastern shore of Lake Ontario, with the entrance to the St Lawrence River dividing Upper Canada from New York State at upper right. At the top of the map is the Royal Navy base of Kingston, to the right the US Navy base of Sackets Harbour and at the bottom the US fort of Oswego, site of the British assault on 6 May 1814. The distance across the lake from Kingston to Oswego is about 45 nautical miles.

Another 1815 aquatint of the Battle of Oswego based on a drawing by Royal Marines officer present at the action - in this case Lieutenant John Hewett, who climbed the flagpole of the fort and took down the Stars and Stripes. In the foreground HMS Prince Regent flies the broad pennant of Sir James Yeo; beyond that the British forces are landing and forming up to attack the Americans, who are on the lower slope opposite with the fort behind them. The entrance to the Oswego river, which allowed the Americans to bring up supplies and armaments from New York, is to the right (National Archives of Canada).

The Battle of Fort Oswego and the subsequent blockade was to be Prince Regent’s only active service. In the event, only a few of the American guns were discovered at Oswego and, despite the blockade, the remainder got through to Sackets Harbour, ensuring American supremacy on the Lake after the completion of their own more heavily armed frigates in July. The tables were turned yet again with the completion of the huge three-decker HMS St Lawrence at Kingston in September, but the war ended that winter and she never fired her guns in anger. By July 1815, Thomas Strickland, a shipwright tasked with surveying the ships, described the vessels at Kingston as swinging at their moorings with their top masts removed, laid up and housed over. Only Prince Regent, which had been renamed HMS Kingston in December 1814, remained in commission, serving as a headquarters and a floating barracks.

A colour aquatint of 1828 by James Gray showing Kingston from Fort Henry, with the Royal Navy Dockyard (site of the present Royal Military College of Canada) in the centre and the town beyond. The housed-over ship behind the soldier's bayonet is probably HMS St Lawrence, and that above the solitary lady with the pink top and black hat HMS Prince Regent, renamed HMS Kingston (National Archives of Canada).

Despite their reduction after the war, the laid-up ships in Navy Bay at Kingston still presented a dramatic vista; Lieutenant Francis Hall of the 14th Light Dragoons, in his Travels in Canada and the United States, 1816 and 1817, described how you come by ' ...uncultivated islands, and an uninterrupted line of wooden shore, seem conducting you to the heart of a wilderness, known only to the hunter, and his prey: you emerge from a wood, double a headland, and a fleet of ships lies before you, several of which are as large as any on the ocean.’ The Rush-Bagot agreement of 1817, reducing naval forces on the Great Lakes, ended the career of the squadron, with the ships being put ‘in ordinary’ and suffering badly from leaking and dry rot by 1819, little surprise to the surveyors who knew they were ‘built of green materials and of a bad quality.’ By 1826 they were described as half-sunken, and only six years after that HMS Kingston had disappeared from the Navy List, having been sold and partly broken up in 1832-3. Finally, some time between 1829 and 1843, the hulks of Kingston and Burlington – the renamed Princess Charlotte - were pumped out and towed round into Hamilton Cove, later renamed Deadman Bay, where their remains lie in shallow water to this day.

This 1816 map shows, from the left, Kingston town, Kingston harbour, the Royal Navy Dockyard (site of the present Royal Military College of Canada), Navy Bay, the promontory of Fort Henry, and Hamilton Cove, the present Deadman Bay. Today, the wreck of HMS Prince Regent is to be found at the very head of Deadman Bay, only fifty metres or so from shore, HMS Princess Charlotte about a third of the way down the bay and HMS St Lawrence on the opposite shore south-west of Kingston, out of view to the left.

Diving HMS Prince Regent

The wreck at the head of Deadman Bay was visited in 1912 by Toronto newspaperman Charles Snider, whose measurement of its length – just over 160 feet – was later used to identify it as the former HMS Prince Regent, as the length corresponded with the 155 foot gun deck recorded in Strickland’s 1815 survey; the position of the mast steps and the steep frame deadrise has also been shown to correspond with the plans. In 1938, a hard-hat diver was employed by the Fort Henry museum at Kingston to raise artefacts from the second wreck in the bay, now known to be the former Princess Charlotte, including shot, iron ballast blocks and 18 guns, several of them French guns spiked in 1758 by the British when they captured Fort Frontenac – afterwards renamed Kingston - and evidently used as ballast. It seems likely that similar artefacts also existed in the wreck of Prince Regent. In 2000-1 the wreck of Princess Charlotte was surveyed by a team under Dan Walker from Texas A&M University’s Institute of Nautical Archaeology, and all of the War of 1812 hulls off Kingston have been subject to a survey programme by Parks Canada under the direction of Michael Moore. Two excellent publications arising from those projects are listed below.

We found Prince Regent to be an unexpectedly atmospheric dive. Kitting up in the carpark beside the marina on Deadman Bay, we walked down to a small beach and swam towards the head of the Bay. The wreck lies in a backwater, only two to four metres deep, with no boat traffic overhead and only ice and weather being likely to degrade timbers just beneath the surface. We swam over dense masses of weed that rose to within a metre of the surface and obscuring the bottom, and at first wondered whether we would see the wreck. When we did it was an arresting sight, nestled in the weed like the mouldering carapace of a whale. Much of the surface detail of the timbers was obscured by zebra mussels, and covered with thick algae. The hull is heeled over on its port side, with the starboard frames projecting towards the surface like the ribs of a skeleton. The most striking survival is a large part of the stern, including the stern post, gudgeons and a pintle stop. Swimming forward, we saw the unusual mast-steps, formed not from shaped timbers placed on top of the keelson but from gaps in the upper row of the keelson timbers themselves, the sides being made up from timbers bolted on and strengthened with crutches. At many places on the hull we could see where the planking had been attached with iron spikes, and the frames and other timbers with iron bolts.

Surfacing at the bow, my mask half in and half-out of the water, and looking back along Deadman Bay towards Kingston - the eerie image of the timbers shrouded in algae below, and above that the modern yachts of the marina - it seemed as if I was viewing a cross-section through history, and a vivid reminder of the 'war of carpenters', as one contemporary put it, that played such a critical role in deciding the future of North America two centuries ago.

References

Moore, Jonathan, 2014. Frontier frigates and a three-decker: wrecks of the Royal Navy’s Lake Ontario Squadron. In Crisman, J. (ed.), Coffins of the Brave: Lake shipwrecks of the War of 1812. College Station, Texas A&M University Press, pp. 187-218.

Walker, Daniel Robert, 2007. The identity and construction of Wreck Baker: a War of 1812 period Royal Navy Frigate. MA dissertation, Texas A&M University.