David Gibbins's Blog, page 2

November 28, 2020

Three Portuguese merchant’s weights of probable early 16th century date from the wreck of the Schiedam (1684), off Gunwalloe, Cornwall, UK

Gunwalloe Church Cove in heavy seas, with St Winwaloe’s Church visible behind the promontory in the centre. The wreck of the Schiedam lies in the cove of Jangye-ryn beyond, below Halzephron headland (photo: David Gibbins).

In September 2020 over the course of eight dives I excavated and raised the three 56 lb (25.4 kg) copper-alloy weights in this photo from the wreck of the Schiedam, a Dutch-built ship of some 400 tons that was ‘cast away’ near Gunwalloe off the west coast of the Lizard Peninsula on 4 April 1684. The wreck was discovered in 1971 by Anthony Randall, designated under the 1973 Protection of Wrecks Act and since 2016 has been investigated under my direction and that of Mark Milburn, the current Licensees from Historic England for the site. A report on our work has recently been published (Gibbins 2020b). On her final voyage from Holland, the Schiedam was captured by Barbary corsairs off Spain, captured again by the English ten days later and then put to use transporting guns, equipment, horses and people from Tangier in North Africa at the time of its abandonment by the English in 1684. Tangier had been given by the Portuguese to the English king Charles II as a dowry with his wife Catherine of Braganza in 1661, but proved too costly to maintain in the face of Moorish attack and did not live up to expectations as a trading port. The three weights - first spotted by Mark on a dive we did together at the site in 2017, but then deeply buried in sand for almost three years - are of great interest not only as objects in use in Tangier during this period, but also because they originated during the Portuguese occupation of Tangier (1471-1661) and are most probably of very early 16th century date. They are unique among surviving Portuguese weights for their age, size and decoration, and are among the oldest and most unusual artefacts to be recovered from a shipwreck off Cornwall.

Two of the weights as they were first seen on seabed, partly encased in ferrous concretion caused by the corrosion of tools and other iron objects that had surrounded them (photo: David Gibbins).

The Portuguese Royal coat of arms revealed on one of the weights moments after it had been freed from concretion (photo: David Gibbins).

David Gibbins with a weight from the wreck of the Schiedam (photo: Rachel Hipperson).

David Gibbins with a weight from the wreck of the Schiedam (photo: Rachel Hipperson).

David Gibbins with a weight from the wreck of the Schiedam (photo: Rachel Hipperson).

The most striking feature of the weights is the Portuguese royal coat of arms cast in relief on the side, comprising a shield surmounted by a helmet and dragon crest and flanked by armillary spheres, the symbol adopted while still a prince by the future King Manuel 1 (reigned 1495-1521) that became associated with Portuguese maritime domination in the Age of Discovery. The other markings visible on the weights are small symbols of a ship stamped above and below the coat of arms. It seems most likely that the weights were cast in a gun foundry, where expertise in bronze casting would have been found at a time when many cannon were made of bronze. The steps in gun-founding described by Biringuccio (1540) give an idea of how the weights may have been formed. Whereas each gun was unique, with the forming of the mould requiring the destruction of the model inside, the wax and clay models for the weights would have been created with a reusable wooden mould that would have allowed many castings, as is seen in the identical shapes of the three weights. Similarly, the decorations would have been created in wax in reusable wooden moulds, as is evidenced in the identical appearance of the armillary spheres and the coats of arms but with slight differences in their alignment resulting from the wax models being applied individually to the surface of the weight models. Expertise in casting ornamentation such as this existing in the cannon foundries, with many Portuguese bronze guns of the 16th century having similar relief decoration, as well as in the casting of rings similar to the carrying handle on the weights, with many guns of the period having lifting-loops (Kennard 1986: 11).

The coat of arms of King Manuel I of Portugal (ruled 1495-1521) on one of the weights, comprising a shield surmounted by a helmet and dragon and flanked by armillary spheres. The shield contains five ‘escutcheons’ arranged as a quincunx and is bordered by fourteen small castles (the castles are thought to represent the vanquished fortresses of the Moors during the Reconquista). The dragon - a symbol of the Royal House of Avis of Portugal (1385-1580) - has its wings swept to the right and its tongue extended. The armillary sphere (esfera armilar in Portuguese), showing the movement of celestial bodies (armilla is Latin for bracelet or arm ring), has the line of the ecliptic going from lower left to upper right, a less common depiction than the other way around (photos: David Gibbins).

The weights are of octagonal shape 19 cm across the base and 33 cm high, with the base tapering to narrow shoulders and a large carrying ring on top, all formed as a single bronze casting. The Museu de Metrologia at Lisbon has three octagonal weights of similar shape and size but from different moulds and weighing 29.3-29.4 kg, corresponding to two arrobas (half a quintal, a meio-quintal) in the Portuguese weight system. Several of these weights in the museum have a small stamp of an armillary sphere and one (MM 408) has a relief moulding of the shield on the side, surmounted by a crown. That weight is also stamped with the ‘gauging’ dates of 1688, 1772, 1811 and 1818, showing when the weight was tested and revealing the potential longevity of a weight of this type. The date of manufacture of this weight is unknown, but the gauging date of 1688 is the earliest recorded for a weight of this type in the museum; many earlier weights and standards were lost in the catastrophic earthquake of 1755 that destroyed much of Lisbon. No other weights are known with the relief decoration of the two armillary spheres and the crested shield seen on the Schiedam weights (Antonio Neves, pers. comm.).

The weight of the Schiedam weights, 56 pounds (24.4 kg), corresponds to half a hundredweight (cwt) in the English avoirdupois system. In the Portuguese system, the nearest equivalent to the hundredweight was the heavier quintal; accordingly, the Schiedam weights at their time of manufacture should have been half-quintal weights like those in the Museu Metrologica of about 29.3 kg, just under 4 kg heavier than their present weight. This inconsistency is explained by a 1663 Proclamation by the Governor of Tangier, Lord Teviot, to the inhabitants of the city, ‘to establish weights, measures and coinage as used in London’ (British Library, Sloane mss 3299, July 1663, F.85b). As the Portuguese weights in Tangier at the time would have been larger than their nearest English equivalent, it would have a straightforward if time-consuming matter to cut and file them down to size. One of the Schiedam weights shows evidence of filing at the shoulder for weight adjustment, though the main technique for removing nearly 4 kg of bronze would have been to saw about half an inch off the base. Two of the weights have smoothed bases but one has clear saw marks, of the type that anyone used to sawing wood will be familiar with from making slight adjustments in the direction mid-way. A comparison can again be made with bronze gun manufacture, in which it could take several days for a team of men using a thin saw with small teeth to cut off the ‘feeding head’ of the gun after casting, where bronze had solidified outside the muzzle (Kennard 1986: 16).

The top of one of the weights showing where damage or a casting flaw had been filled in with copper (David Gibbins).

The base of one of the weights showing saw marks, almost certainly caused when the weight was being cut down from its original Portuguese size to the English half hundredweight. Width of base: 19 cm (David Gibbins).

A large balance beam scale in the Museu Militar in Lisbon with an 18th century date on the beam (photo courtesy of Harold A. Skaarup).

Remarkably, an account of weights at Tangier of this size exists in the diary of John Luke, secretary to the Governor Lord Middleton in the early 1670s. On 23 March 1672 he wrote that soldiers of the garrison suspected that they had been short-changed in their provisions, leading Lord Middleton to go ‘ … in person and see all the weights tried, which were found right, but one half hundred weight that had been used of late could not be found’ (Luke 1670-3: 111). This shows how weights could be used for purposes other than purely commercial transactions, especially at Tangier where adequate victualling of the garrison was a constant issue. Half-hundredweight or half-quintal weights were especially useful as they could be managed by one man, but were sufficiently heavy that only a few of them might be needed on a large balance beam scale (called by the Portuguese a cabrilha) to weigh a typical cargo consignment, with the exact calculation being reached with the addition of smaller weights from a set.

The weights were probably stored either in the old Portuguese harbour area or on the newly constructed great Mole, perhaps in one of the buildings that can be seen in the etchings of Tangier made by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1669. The Schiedam was specifically tasked to take the workmen, tools and other stores from the Mole back to England, so it seems most likely that the weights – and perhaps others of different sizes yet to be discovered at the wreck, or salvaged soon after the wrecking – came from there. They were probably being taken back to England with a view to the bronze being recycled; weights emblazoned with the Portuguese coat of arms may have been acceptable for continued use in English Tangier, but are unlikely to have been so in England itself.

‘Prospect of Tangier from the S.E.’ by Wenceslaus Hollar, who went to Tangier in 1668 to draw the town and fortifications. The ‘Old Mould’ (sic), the mole or pier from the Portuguese period, can be seen in the centre of the image, with the new mole built by the Engish extending out to the right (Wenceslaus Hollar Collection, Fisher Library, University of Toronto).

Left and centre, two examples the identical small stamp (1 cm across) that appears above and below the coat of arms on each of the weights. The image to the right is the identical stamp on a one-arroba nested weight of the Manueline issue (1499-1503/4) in the Núcleo Museuológico de Metrologia/Casa da Balança, Évora (Lopes 2018, Fig 9). The image shows a ship of late mediaeval appearance with a single mast and raked yard, with four rolls of waves below and a large crow perched on the stern and another on the forecastle, both facing inwards (photo: David Gibbins).

The small stamp above and below the coat of arms may be the best dating evidence for the weights. It shows the symbol of Lisbon – a ship with crows facing inwards on the stern and forecastle, in a scene from the story of St Vincent, patron Saint of Lisbon. This particular stamp is only seen elsewhere on the so-called ‘Manueline’ nested cup weights issued by King Manuel I to all Portuguese cities in 1503-4 as part of his reform of the weights system (Lopes 2018, 2019). The nested weights, of which at least 128 were issued, were ordered from Flanders in 1499, and those for Lisbon would have been stamped on their arrival in the city. It is clear that the same stamp was used in Lisbon on the Schiedam weights. The stamp could have remained in use for some time after this date, but in the capacity standards of King Sebastian, dated to 1575, the Lisbon mark – while showing the same symbolic content – is of a different design (Luís Seabra Lopes and Antonio Neves, pers. comm.). The evidence of the stamp therefore strongly suggests a date for the weights in the first half of the 16th century, with the possibility that they were issued at the same time as the nested weights as part of the Manueline reform during the early part of his reign.

Manuel’s coat of arms with flanking armillary spheres in the Foral (Charter) of Lisbon, 1500 (Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa).

The shield flanked by armillary spheres on the Torre de Belém in Lisbon, built by Manuel I in 1514-19 to guard the entrance to the Tagus river.

Shield with 14 castles in the Livro Carmesin of 1502 (Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa).

Shield with 14 castles, flanking armillary spheres and a dragon on the Manueline charter for the city of Évora, 1501 (Arquivo Distrital de Évora).

Shield with 14 castles and flanking armillary spheres in the Leitura Nova of 1504 (Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo).

The Royal coat of arms of Portugal on a seal attached to a letter dated 1507, showing the helmet and dragon crest very similar in configuration to the crest on the Schiedam weights (Sousa 1738, p 43 no LXXII and pl. O. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal).

Manuel’s reform of the weights was carried out in conjunction with his renewal of the municipal charters of cities and towns in Portugal. These new charters include the Royal coat of arms flanked by two armillary spheres, as on the Schiedam weights. The same arrangement is found on sculptural decoration on ‘Manueline’ architecture, including the Torre de Belém in Lisbon – the point of departure for Portuguese voyages of discovery – and the nearby Jerόnimos Monastery. This arrangement of a shield flanked by two armillary spheres appears to be particular to the reign of Manuel 1. From Manuel’s reign onwards the number of castles in the border of the shield was most often 7, but shields with larger numbers of castles are known from the early part of his reign - including two of the depictions shown here, on the Lisbon charter of 1500 and the royal seal of 1507, respectively with 11 and 13 castles. The only known parallels for the 14 castles of the Schiedam weights are also shown here, on the Manueline charter for the city of Évora (1501), on a shield in the Lisbon Livro Carmesin of 1503 and in the two frontispieces of the Leitura Nova of 1504 (Garcia 2005: 43). All of these examples and most later depictions of the Royal coat of arms have the shield surmounted by a crown, but the crest of the helmet and dragon as on the Schiedam weights is also seen on several depictions from the reign of Manuel shown here as well.

The Royal coat of arms of Portugal with the helmet and dragon crest as depicted by Antόnio Godinho, who was ‘Escrivão da Câmara’ (‘Clerk of the Chamber’) under King João III but began his heraldry in the final years of the reign of Manuel I (Godinho 1517-28, Fol. 6v. Arquivio Nacional da Torre de Tombo).

Apart from the Manueline nested weights, the most extensive survival of bronze relief-cast Portuguese coats of arms and armillary spheres is on guns of the 16th century. These include 26 guns in the Museu Militar in Lisbon (itself housed in a gun foundry of the period)(Marzia 2014), several in the Museu de Marinha in Lisbon, several in the Museu de Angra in the Azores (Hoskins 2003), one in the British Museum (Smith 1995), several at the Portuguese ambassador’s residence at Bangkok, one at Tangier itself - datable to c. 1520, and undoubtedly a gun that arrived in Tangier with the Moors after the English had left (Kennard 1986: 106) - and a number from wrecks and other underwater contexts around the world, including the mid-16th century São Bento wreck off South Africa (Auret and Maggs 1982), a mid-16th century wreck in the Seychelles (Blake and Green 1986), a wreck recently discovered in the Tejo (Tagus) river in Portugal, and - the only other known example from UK waters - ‘an Old Piece of Ordnance, which some Fishermen dragged out of the Sea near the Goodwin Sands, in 1775’, reported in Archaeologia magazine by Edward King, Esq., F.R.S., in one of the first scholarly accounts of an underwater find in British waters (King mistakenly associates the letters CFR in a cartouche on the gun with a mediaeval Portuguese king, whereas in fact they are those of the gun-founder of the 16th century: see Smith 2000: 184 and Smith 1995: 198, 200).

Illustration in Archaeologia magazine from 1779 of the castings on a bronze swivel gun found in the Goodwyn Sands off Kent, by Edward King, F.R.S., F.S.A. Although possibly not an entirely accurate sketch - the escutcheons in the shield should number five, in a quincunx - the large number of castles shown in the border is of interest as a comparison with the Schiedam weights.

Of these guns that can be dated, either by a datable wreck context, a date on the gun itself, the known dates of the gun-founder or on stylistic grounds, all are of the 16th century. All have the shield capped by a crown rather than a helmet and dragon, and none of the decorations are from the same casting moulds as the Schiedam examples. Most have a single armillary sphere above or below the shield. Only three are known with two or more spheres flanking the shield, all in the Museu Militar in Lisbon (Marzia 2014): one (MML/01500) with the shield on the chase and the two spheres on the second reinforce, and a Manueline date (1495-1521) suggested on stylistic and decorative grounds; another (MML/0020), dated 1533, with two spheres flanking the shield on each side; and a third (MML/1510) with the characteristic Manueline arrangement of spheres flanking a shield, but dated to 1578. This is the only known example of that arrangement not of Manueline date and is the latest dated of these 16th century guns bearing armillary spheres, but it was on a highly decorative piece dedicated to King Sebastian in the year of the battle of Alcácer Quibir against the Moroccans - in which Sebastian disappeared, presumed killed – and the gun-founder may consciously have used symbolism that harked back to the achievements of Sebastian’s great-grandfather Manuel.

Another remarkable example of a bronze-cast shield and armillary sphere is on an astrolabe discovered in 2014 at the Sodré shipwreck site at Al Hallaniyah, Oman, where the Esmeralda and São Padre from Vasco da Gama’s fourth armada were wrecked in 1503 (Mearns et al. 2019). The shield, surmounted by a crown, appears to have 11 castles in the border, and the sphere has the ecliptic going from lower right to upper left. The certain date of the astrolabe – manufactured before the armada set off from Lisbon in February 1502 – puts it very close to the date of the Manueline nest weights as well as the new city charters with their shields and armillary spheres. In common with the Schiedam weights, the astrolabe is the earliest of that type of artefact known and unique in having these decorative embellishments characteristic of the reign of Manuel. The evidence reviewed here strongly suggests that the Schiedam weights are also of Manueline date, possibly from the early years of the 16th century - making them unique artefacts not only from English Tangier in the 17th century but also from the Portuguese Age of Discovery more than a century and a half earlier.

Note

For the association of Samuel Pepys with the wreck of the Schiedam see Gibbins 2020a and 2020b, and for discussion of Dutch weights found at the nearby Mullion Pin Wreck (1667) see Gibbins 2019a and 2019b. Frequent updates on our discoveries on wrecks off the Lizard Peninsula can be found on our Facebook page Cornwall Maritime Archaeology.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Hefin Meara, Maritime Archaeologist at Historic England, and to Alison James, formerly of Historic England, for granting permission for the recovery of these artefacts and for their assistance with this project. The weights have been declared to the UK Receiver of Wreck and are currently under conservation in preparation for museum display. For assistance in the identification of these artefacts, and for much comparative material and discussion, I am grateful to Antonio Neves (Curator, Museu de Metrologia, Lisboa), Luís Seabra Lopes (Associate Professor, University of Aveiro) and Ritzo Holtman (editor of the journal Meten & Wegen). I am also grateful to Harold A. Skaarup, Vittorio Serafin, Renato Gianni Ridella, Ruth Rhynas Brown and Gonçalo Bioucas of The Big Cannon Project for assistance in identifying guns bearing the Portuguese coat of arms, and to Harold A. Skarrup for allowing me to use his photo of a scale in the Museu Militar in Lisbon.

Click here to read this article by Dalya Alberge in the London Daily Telegraph on the discovery, published on page 3 of the print edition of the newspaper and online on 29 November 2020.

References

Auret, C. and Maggs, T., 1982. The Great Ship São Bento: remains from a mid-sixteenth century Portuguese wreck on the Pondoland coast. Annals of the Natal Museum 25.1: 1-39.

Biringuccio, V., 1540. Pirotechnia. Venice. Reprint, 1966, trans. C.S. Smith and M.T. Gnudi, Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

Blake, W. and Green, J., 1986. A mid-XVI century Portuguese wreck in the Seychelles. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 15.1: 1-23.

Garcia, J.M., 2005. As Illuminuras de 1502 do “Livro Carmesim” e a Iconologia Manuelina. Cadernos do Arquivo Municipal 8 (11): 38-55.

Gibbins, David, 2019a. A two-pound Amsterdam blokgewicht (block weight) from the Mullion Pin Wreck (1667), off Cornwall, England. www.davidgibbins.com

Gibbins, David, 2019b. Three more marked merchant weights from the Mullion Pin Wreck (1667), off Cornwall, England. www.davidgibbins.com

Gibbins, David, 2020a. Samuel Pepys, English Tangier and the wreck of the Schiedam (1684). www.davidgibbins.com

Gibbins, David, 2020b. ‘The Schiedam: piracy, Samuel Pepys and English Tangier.’ Wreckwatch 3-4 (Winter 2020): 112-17.

Godinho, A., 1517-28. Livro da Nobreza e da Perfeição das armas dos Reis Cristãos e nobres linhagens dos Reinos e Senhorios de Portugal. Arquivio Nacional da Torre de Tombo.

Hoskins, S.G., 2003. 16th century cast-bronze ordnance at the Museu de Angra do Heroísmo. M.A. Thesis, Texas A&M University.

Kennard, A.N., 1986. Gunfounding and gunfounders. London: Arms and Armour Press.

King, E., 1779. An account of an Old Piece of Ordnance, which some Fishermen dragged out of the Sea near the Goodwin Sands, in 1775. Archaeologia 5: 147-59.

Lopes, Luís Seabra, 2018, As pilhas de pesos de Dom Manuel I: contributo para a sua caracterização e avaliação. Portvgalia, Novo Série 39: 217-51

Lopes, Luís Seabra, 2019. The distribution of weight standards to Portuguese cities and towns in the early 16th century. Administrative, demographic and economic factors. Finisterra LIV (112): 45-70

Luke, J. 1670-3: Kaufman, H.A. (ed), 1958. Tangier at High Tide: the Journal of John Luke, 1670-73. Geneva: Librarie E. Droz/Paris: Librairie Minard.

Marzia, E.M. de M.., 2014. Inventário da artilharia histórica dos séculos XIV a XVI do Museu Militar de Lisboa: bases para uma proposta de salvaguarda e valorização. Universidade de Évora.

Mearns, D.L., Warnett, J.M. and Williams, M.A., 2019. An early Portuguese mariner’s astrolabe from the Sodré wreck site, Al Hallaniyah, Oman. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 48.2: 495-506

Smith, R.B., 2000. A comparative study of 16th century Portuguese and East Mediterranean artillery. Anatolia Moderna 9: 183-210.

Smith, R.D., 1995. A 16th century Portuguese bronze breech-loading swivel gun. Militaria. Revisto de Cultura Militar 7. Servicio de Publicaciones, UCM, Madrid, 197-205

Sousa, A.C. de, 1738, Historia genealogica de Casa Real Portugueza: desde a sua origem até o presente, com as Familias illustres, que procedem dos Reys, e dos Serenissimos Duques de Braganca: justificada com instrumentos, e escritores de inviolavel fé: e offerecida a El Rey João V. Tomo IV. Lisboa. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

Three Portuguese merchant’s weights of probable early 16th century date from the wreck of the Schiedam (1684), Gunwalloe, Cornwall, UK

Gunwalloe Church Cove in heavy seas, with St Winwaloe’s Church visible behind the promontory in the centre. The wreck of the Schiedam lies in the cove of Jangye-ryn beyond, below Halzephron headland (photo: David Gibbins).

In September 2020 over the course of eight dives I excavated and raised the three 56 lb (25.4 kg) bronze weights in this photo from the wreck of the Schiedam, a Dutch-built ship of some 400 tons that was ‘cast away’ near Gunwalloe off the west coast of the Lizard Peninsula on 4 April 1684. The wreck was discovered in 1971 by Anthony Randall, designated under the 1973 Protection of Wrecks Act and since 2016 has been investigated under my direction and that of Mark Milburn, the current Licensees from Historic England for the site. On her final voyage from Holland, the Schiedam was captured by Barbary corsairs off Spain, captured again by the English ten days later and then put to use transporting guns, equipment, horses and people from Tangier in North Africa at the time of its abandonment by the English in 1684. Tangier had been given by the Portuguese to the English king Charles II as a dowry with his wife Catherine of Braganza in 1661, but proved too costly to maintain in the face of Moorish attack and did not live up to expectations as a trading port. The three weights are of great interest not only as objects in use in Tangier during this period, but also because they originated during the Portuguese occupation of Tangier (1471-1661) and are probably of early 16th century date. They are unique among surviving Portuguese weights for their age, size and decoration, and are among the oldest and most unusual artefacts to be recovered from a shipwreck off Cornwall.

Two of the weights as they were first seen on seabed, partly encased in ferrous concretion caused by the corrosion of tools and other iron objects that had surrounded them (photo: David Gibbins).

The Portuguese Royal coat of arms revealed on one of the weights moments after it had been freed from concretion (photo: David Gibbins).

David Gibbins with a weight from the wreck of the Schiedam (photo: Rachel Hipperson).

David Gibbins with a weight from the wreck of the Schiedam (photo: Rachel Hipperson).

David Gibbins with a weight from the wreck of the Schiedam (photo: Rachel Hipperson).

The most striking feature of the weights is the Portuguese royal coat of arms cast in relief on the side, comprising a shield surmounted by a helmet and dragon crest and flanked by armillary spheres, the symbol adopted while still a prince by the future King Manuel 1 (reigned 1495-1521) that became associated with Portuguese maritime domination in the Age of Discovery. The other markings visible on the weights are small symbols of a ship stamped above and below the coat of arms. It seems most likely that the weights were cast in a gun foundry, where expertise in bronze casting would have been found at a time when many cannon were made of bronze. The steps in gun-founding described by Biringuccio (1540) give an idea of how the weights may have been formed. Whereas each gun was unique, with the forming of the mould requiring the destruction of the model inside, the wax and clay models for the weights would have been created with a reusable wooden mould that would have allowed many castings, as is seen in the identical shapes of the three weights. Similarly, the decorations would have been created in wax in reusable wooden moulds, as is evidenced in the identical appearance of the armillary spheres and the coats of arms but with slight differences in their alignment resulting from the wax models being applied individually to the surface of the weight models. Expertise in casting ornamentation such as this existing in the cannon foundries, with many Portuguese bronze guns of the 16th century having similar relief decoration, as well as in the casting of rings similar to the carrying handle on the weights, with many guns of the period having lifting-loops (Kennard 1986: 11).

The coat of arms of King Manuel I of Portugal (ruled 1495-1521) on one of the weights, comprising a shield surmounted by a helmet and dragon and flanked by armillary spheres. The shield contains five ‘escutcheons’ arranged as a quincunx and is bordered by fourteen small castles (the castles are thought to represent the vanquished fortresses of the Moors during the Reconquista). The dragon - a symbol of the Royal House of Avis of Portugal (1385-1580) - has its wings swept to the right and its tongue extended. The armillary sphere (esfera armilar in Portuguese), showing the movement of celestial bodies (armilla is Latin for bracelet or arm ring), has the line of the ecliptic going from lower left to upper right, a less common depiction than the other way around (photos: David Gibbins).

The weights are of octagonal shape 19 cm across the base and 33 cm high, with the base tapering to narrow shoulders and a large carrying ring on top, all formed as a single bronze casting. The Museu de Metrologia at Lisbon has three octagonal weights of similar shape and size but from different moulds and weighing 29.3-29.4 kg, corresponding to two arrobas (half a quintal, a meio-quintal) in the Portuguese weight system. Several of these weights in the museum have a small stamp of an armillary sphere and one (MM 408) has a relief moulding of the shield on the side, surmounted by a crown. That weight is also stamped with the ‘gauging’ dates of 1688, 1772, 1811 and 1818, showing when the weight was tested and revealing the potential longevity of a weight of this type. The date of manufacture of this weight is unknown, but the gauging date of 1688 is the earliest recorded for a weight of this type in the museum; many earlier weights and standards were lost in the catastrophic earthquake of 1755 that destroyed much of Lisbon. No other weights are known with the relief decoration of the two armillary spheres and the crested shield seen on the Schiedam weights (Antonio Neves, pers. comm.).

The weight of the Schiedam weights, 56 pounds (24.4 kg), corresponds to half a hundredweight (cwt) in the English avoirdupois system. In the Portuguese system, the nearest equivalent to the hundredweight was the heavier quintal; accordingly, the Schiedam weights at their time of manufacture should have been half-quintal weights like those in the Museu Metrologica of about 29.3 kg, just under 4 kg heavier than their present weight. This inconsistency is explained by a 1663 Proclamation by the Governor of Tangier, Lord Teviot, to the inhabitants of the city, ‘to establish weights, measures and coinage as used in London’ (British Library, Sloane mss 3299, July 1663, F.85b). As the Portuguese weights in Tangier at the time would have been larger than their nearest English equivalent, it would have a straightforward if time-consuming matter to cut and file them down to size. One of the Schiedam weights shows evidence of filing at the shoulder for weight adjustment, though the main technique for removing nearly 4 kg of bronze would have been to saw about half an inch off the base. A comparison can again be made with bronze gun manufacture, in which it could take several days for a team of men using a thin saw with small teeth to cut off the ‘feeding head’ of the gun after casting, where bronze had solidified outside the muzzle (Kennard 1986: 16).

A large balance beam scale in the Museu Militar in Lisbon with an 18th century date on the beam (photo courtesy of Harold A. Skaarup).

Remarkably, an account of weights at Tangier of this size exists in the diary of John Luke, secretary to the Governor Lord Middleton in the early 1670s. On 23 March 1672 he wrote that soldiers of the garrison suspected that they had been short-changed in their provisions, leading Lord Middleton to go ‘ … in person and see all the weights tried, which were found right, but one half hundred weight that had been used of late could not be found’ (Luke 1670-3: 111). This shows how weights could be used for purposes other than purely commercial transactions, especially at Tangier where adequate victualling of the garrison was a constant issue. Half-hundredweight or half-quintal weights were especially useful as they could be managed by one man, but were sufficiently heavy that only a few of them might be needed on a large balance beam scale (called by the Portuguese a cabrilha) to weigh a typical cargo consignment, with the exact calculation being reached with the addition of smaller weights from a set.

The weights were probably stored either in the old Portuguese harbour area or on the newly constructed great Mole, perhaps in one of the buildings that can be seen in the etchings of Tangier made by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1669. The Schiedam was specifically tasked to take the workmen, tools and other stores from the Mole back to England, so it seems most likely that the weights – and perhaps others of different sizes yet to be discovered at the wreck, or salvaged soon after the wrecking – came from there. They were probably being taken back to England with a view to the bronze being recycled; weights emblazoned with the Portuguese coat of arms may have been acceptable for continued use in English Tangier, but are unlikely to have been so in England itself.

‘Prospect of Tangier from the S.E.’ by Wenceslaus Hollar, who went to Tangier in 1668 to draw the town and fortifications. The ‘Old Mould’ (sic), the mole or pier from the Portuguese period, can be seen in the centre of the image, with the new mole built by the Engish extending out to the right (Wenceslaus Hollar Collection, Fisher Library, University of Toronto).

Left and centre, two examples the identical small stamp (1 cm across) that appears above and below the coat of arms on each of the weights. The image to the right is the identical stamp on a one-arroba nested weight of the Manueline issue (1499-1503/4) in the Núcleo Museuológico de Metrologia/Casa da Balança, Évora (Lopes 2018, Fig 9). The image shows a ship of late mediaeval appearance with a single mast and raked yard, with four rolls of waves below and a large crow perched on the stern and another on the forecastle, both facing inwards (photo: David Gibbins).

The small stamp above and below the coat of arms may be the best dating evidence for the weights. It shows the symbol of Lisbon – a ship with crows facing inwards on the stern and forecastle, in a scene from the story of St Vincent, patron Saint of Lisbon. This particular stamp is only seen elsewhere on the so-called ‘Manueline’ nested cup weights issued by King Manuel I to all Portuguese cities in 1503-4 as part of his reform of the weights system (Lopes 2018, 2019). The nested weights, of which at least 128 were issued, were ordered from Flanders in 1499, and those for Lisbon would have been stamped on their arrival in the city. It is clear that the same stamp was used in Lisbon on the Schiedam weights. The stamp could have remained in use for some time after this date, but in the capacity standards of King Sebastian, dated to 1575, the Lisbon mark – while showing the same symbolic content – is of a different design (Luís Seabra Lopes and Antonio Neves, pers. comm.). The evidence of the stamp therefore strongly suggests a date for the weights in the first half of the 16th century, with the possibility that they were issued at the same time as the nested weights as part of the Manueline reform during the early part of his reign.

Manuel’s coat of arms with flanking armillary spheres in the Foral (Charter) of Lisbon, 1500 (Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa).

The shield flanked by armillary spheres on the Torre de Belém in Lisbon, built by Manuel I in 1514-19 to guard the entrance to the Tagus river.

Shield with 14 castles in the Livro Carmesin of 1502 (Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa).

Shield with 14 castles, flanking armillary spheres and a dragon on the Manueline charter for the city of Évora, 1501 (Arquivo Distrital de Évora).

Shield with 14 castles and flanking armillary spheres in the Leitura Nova of 1504 (Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo).

The Royal coat of arms of Portugal on a seal attached to a letter dated 1507, showing the helmet and dragon crest very similar in configuration to the crest on the Schiedam weights (Sousa 1738, p 43 no LXXII and pl. O. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal).

Manuel’s reform of the weights was carried out in conjunction with his renewal of the municipal charters of cities and towns in Portugal. These new charters include the Royal coat of arms flanked by two armillary spheres, as on the Schiedam weights. The same arrangement is found on sculptural decoration on ‘Manueline’ architecture, including the Torre de Belém in Lisbon – the point of departure for Portuguese voyages of discovery – and the nearby Jerόnimos Monastery. This arrangement of a shield flanked by two armillary spheres appears to be particular to the reign of Manuel 1. From Manuel’s reign onwards the number of castles in the border of the shield was most often 7, but shields with larger numbers of castles are known from the early part of his reign - including two of the depictions shown here, on the Lisbon charter of 1500 and the royal seal of 1507, respectively with 11 and 13 castles. The only known parallels for the 14 castles of the Schiedam weights are also shown here, on the Manueline charter for the city of Évora (1501), on a shield in the Lisbon Livro Carmesin of 1503 and in the two frontispieces of the Leitura Nova of 1504 (Garcia 2005: 43). All of these examples and most later depictions of the Royal coat of arms have the shield surmounted by a crown, but the crest of the helmet and dragon as on the Schiedam weights is also seen on several depictions from the reign of Manuel shown here as well.

The Royal coat of arms of Portugal with the helmet and dragon crest as depicted by Antόnio Godinho, who was ‘Escrivão da Câmara’ (‘Clerk of the Chamber’) under King João III but began his heraldry in the final years of the reign of Manuel I (Godinho 1517-28, Fol. 6v. Arquivio Nacional da Torre de Tombo).

Apart from the Manueline nested weights, the most extensive survival of bronze relief-cast Portuguese coats of arms and armillary spheres is on guns of the 16th century. These include 26 guns in the Museu Militar in Lisbon (itself housed in a gun foundry of the period)(Marzia 2014), several in the Museu de Marinha, also in Lisbon, several in the Museu de Angra in the Azores (Hoskins 2003), one in the British Museum (Smith 1995), several at the Portuguese ambassador’s residence at Bangkok, and a number from wrecks and other underwater contexts around the world, including the mid-16th century São Bento wreck off South Africa (Auret and Maggs 1982), a mid-16th century wreck in the Seychelles (Blake and Green 1986), a wreck recently discovered in the Tejo (Tagus) river in Portugal, and - the only other known example from UK waters - ‘an Old Piece of Ordnance, which some Fishermen dragged out of the Sea near the Goodwin Sands, in 1775’, reported in Archaeologia magazine by Edward King, Esq., F.R.S., in one of the first scholarly accounts of an underwater find in British waters (King mistakenly associates the letters CFR in a cartouche on the gun with a mediaeval Portuguese king, whereas in fact they are those of the gun-founder of the 16th century: see Smith 2000: 184 and Smith 1995: 198, 200).

Illustration in Archaeologia magazine from 1779 of the castings on a bronze swivel gun found in the Goodwyn Sands off Kent, by Edward King, F.R.S., F.S.A. Although possibly not an entirely accurate sketch - the escutcheons in the shield should number five, in a quincunx - the large number of castles shown in the border is of interest as a comparison with the Schiedam weights.

Of these guns that can be dated, either by a datable wreck context, a date on the gun itself, the known dates of the gun-founder or on stylistic grounds, all are of the 16th century. All have the shield capped by a crown rather than a helmet and dragon, and none of the decorations are from the same casting moulds as the Schiedam examples. Most have a single armillary sphere above or below the shield. Only three are known with two or more spheres flanking the shield, all in the Museu Militar in Lisbon (Marzia 2014): one (MML/01500) with the shield on the chase and the two spheres on the second reinforce, and a Manueline date (1495-1521) suggested on stylistic and decorative grounds; another (MML/0020), dated 1533, with two spheres flanking the shield on each side; and a third (MML/1510) with the characteristic Manueline arrangement of spheres flanking a shield, but dated to 1578. This is the only known example of that arrangement not of Manueline date and is the latest dated of these 16th century guns bearing armillary spheres, but it was on a highly decorative piece dedicated to King Sebastian in the year of the battle of Alcácer Quibir against the Moroccans - in which Sebastian disappeared, presumed killed – and the gun-founder may consciously have used symbolism that harked back to the achievements of Sebastian’s great-grandfather Manuel.

Another remarkable example of a bronze-cast shield and armillary sphere is on an astrolabe discovered in 2014 at the Sodré shipwreck site at Al Hallaniyah, Oman, where the Esmeralda and São Padre from Vasco da Gama’s fourth armada were wrecked in 1503 (Mearns et al. 2019). The shield, surmounted by a crown, appears to have 11 castles in the border, and the sphere has the ecliptic going from lower right to upper left. The certain date of the astrolabe – manufactured before the armada set off from Lisbon in February 1502 – puts it very close to the date of the Manueline nest weights as well as the new city charters with their shields and armillary spheres. In common with the Schiedam weights, the astrolabe is the earliest of that type of artefact known and unique in having these decorative embellishments characteristic of the reign of Manuel. The evidence reviewed here strongly suggests that the Schiedam weights are also of Manueline date, possibly from the early years of the 16th century - making them unique artefacts not only from English Tangier in the 17th century but also from the Portuguese Age of Discovery more than a century and a half earlier.

Note

For the association of Samuel Pepys with the wreck of the Schiedam see Gibbins 2020, and for discussion of Dutch weights found at the nearby Mullion Pin Wreck (1667) see Gibbins 2019a and 2019b. Frequent updates on our discoveries on wrecks off the Lizard Peninsula can be found on our Facebook page Cornwall Maritime Archaeology.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Hefin Meara, Maritime Archaeologist at Historic England, and to Alison James, formerly of Historic England, for granting permission for the recovery of these artefacts and for their assistance with this project. The weights have been declared to the UK Receiver of Wreck and are currently under conservation in preparation for museum display. For assistance in the identification of these artefacts, and for much comparative material and discussion, I am grateful to Antonio Neves (Curator, Museu de Metrologia, Lisboa), Luís Seabra Lopes (Associate Professor, University of Aveiro) and Ritzo Holtman (editor of the journal Meten & Wegen). I am also grateful to Harold A. Skaarup, Vittorio Serafin and Gonçalo Bioucas of The Big Cannon Project for pointing me to guns bearing the Portuguese coat of arms, and to Harold A. Skarrup for allowing me to use his photo of a scale in the Museu Militar in Lisbon.

References

Auret, C. and Maggs, T., 1982. The Great Ship São Bento: remains from a mid-sixteenth century Portuguese wreck on the Pondoland coast. Annals of the Natal Museum 25.1: 1-39.

Biringuccio, V., 1540. Pirotechnia. Venice. Reprint, 1966, trans. C.S. Smith and M.T. Gnudi, Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

Blake, W. and Green, J., 1986. A mid-XVI century Portuguese wreck in the Seychelles. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 15.1: 1-23.

Garcia, J.M., 2005. As Illuminuras de 1502 do “Livro Carmesim” e a Iconologia Manuelina. Cadernos do Arquivo Municipal 8 (11): 38-55.

Gibbins, David, 2019a. A two-pound Amsterdam blokgewicht (block weight) from the Mullion Pin Wreck (1667), off Cornwall, England. www.davidgibbins.com

Gibbins, David, 2019b. Three more marked merchant weights from the Mullion Pin Wreck (1667), off Cornwall, England. www.davidgibbins.com

Gibbins, David, 2020. Samuel Pepys, English Tangier and the wreck of the Schiedam (1684). www.davidgibbins.com

Godinho, A., 1517-28. Livro da Nobreza e da Perfeição das armas dos Reis Cristãos e nobres linhagens dos Reinos e Senhorios de Portugal. Arquivio Nacional da Torre de Tombo.

Hoskins, S.G., 2003. 16th century cast-bronze ordnance at the Museu de Angra do Heroísmo. M.A. Thesis, Texas A&M University.

Kennard, A.N., 1986. Gunfounding and gunfounders. London: Arms and Armour Press.

King, E., 1779. An account of an Old Piece of Ordnance, which some Fishermen dragged out of the Sea near the Goodwin Sands, in 1775. Archaeologia 5: 147-59.

Lopes, Luís Seabra, 2018, As pilhas de pesos de Dom Manuel I: contributo para a sua caracterização e avaliação. Portvgalia, Novo Série 39: 217-51

Lopes, Luís Seabra, 2019. The distribution of weight standards to Portuguese cities and towns in the early 16th century. Administrative, demographic and economic factors. Finisterra LIV (112): 45-70

Luke, J. 1670-3: Kaufman, H.A. (ed), 1958. Tangier at High Tide: the Journal of John Luke, 1670-73. Geneva: Librarie E. Droz/Paris: Librairie Minard.

Marzia, E.M. de M.., 2014. Inventário da artilharia histórica dos séculos XIV a XVI do Museu Militar de Lisboa: bases para uma proposta de salvaguarda e valorização. Universidade de Évora.

Mearns, D.L., Warnett, J.M. and Williams, M.A., 2019. An early Portuguese mariner’s astrolabe from the Sodré wreck site, Al Hallaniyah, Oman. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 48.2: 495-506

Smith, R.B., 2000. A comparative study of 16th century Portuguese and East Mediterranean artillery. Anatolia Moderna 9: 183-210.

Smith, R.D., 1995. A 16th century Portuguese bronze breech-loading swivel gun. Militaria. Revisto de Cultura Militar 7. Servicio de Publicaciones, UCM, Madrid, 197-205

Sousa, A.C. de, 1738, Historia genealogica de Casa Real Portugueza: desde a sua origem até o presente, com as Familias illustres, que procedem dos Reys, e dos Serenissimos Duques de Braganca: justificada com instrumentos, e escritores de inviolavel fé: e offerecida a El Rey João V. Tomo IV. Lisboa. Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

Samuel Pepys, English Tangier and the wreck of the Schiedam (1684)

‘Prospect of Tangier from the East’ by Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-77), who was sent by King Charles II in 1668 to draw the town and its fortifications. The great ‘Mole’ can be seen under construction to the right, with workmen visible at the end, a gun battery facing seaward and various buildings. In early 1684 the Schiedam was tasked to bring back the ‘Molemen’ and their families as well as equipment and stores from the Mole (Wenceslaus Hollar Collection, Fisher Library, University of Toronto).

A view of four of the guns on the wreck of the Schiedam, still aligned muzzle to breech as they had been in the hold of the ship. With the ship tasked to transport material from the Mole at Tangier, it seems possible that these guns were from the battery on the seaward side of the Mole visible in the Hollar etching above (photo: David Gibbins).

The Schiedam, more fully ye Groette Schedam van Horn (the ‘Great Schiedam of Horn’), was a ship of some 400 tons built at Hoorn in Holland and wrecked near Gunwalloe off the west coast of the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall on 4 April 1684. She was a fluyt, called by the English a ‘flyboat’, a type of wide-bellied cargo vessel with minimal armament and a small crew. The wreck was discovered in the shallow cove of Jangye-ryn in 1971 by Anthony Randall, was designated under the 1973 Protection of Wrecks Act and since 2016 has been investigated under my direction and that of Mark Milburn, the current Licensees from Historic England for the site. Much of the interest of the Schiedam stems from her remarkable final voyage. Having left Holland in late April or early May 1683 with cordage and anchors, she discharged her cargo at Ribadeo on the north coast of Spain and took on timber for Cadiz. On 1 August she was captured by Barbary corsairs, and then ten days later by Captain Cloudesley Shovel in the Royal Navy galley the James. He took her as a Prize to the English colony of Tangier, where she was put to use transporting fresh water from Spain for the English fleet - Tangier was poorly provided with water - and then taking equipment, stores and people back to England when Tangier was abandoned in early 1684. At the time of her wrecking, therefore, she was no longer a merchantman but was a transport vessel of the Royal Navy, termed ‘His Majesty’s Flyboat Scedam (sic) or ‘Schiedam Prize’, with a crew taken from a hulk at Tangier and considered the equivalent of a 6th rate naval ship.

A Dutch fluyt by Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-77), who also etched the image of Tangier above. This is one of the best images of a fluyt and probably gives a good impression of the appearance of the Schiedam, including the minimal armament - the Schiedam had only four small guns, and here you can see one gun and two closed gun ports (Wenceslaus Hollar Collection, Fisher Library, University of Toronto).

A fascinating aspect of the story of the Schiedam is the involvement of Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist who served as Secretary to the Admiralty in London during the reigns of King Charles II and King James II. In early August 1683, the same month that the Schiedam was taken as a Prize, Pepys embarked with a fleet at Portsmouth to help oversee the destruction and evacuation of Tangier. Over the next few months while the Schiedam was often in the harbour Pepys busied himself with his task of compensating the English merchants and other people of the city for their loss of property caused by the evacuation. On the departure of the Schiedam for England, in late February 1684, she had on board Pepys’ friend Henry Shere, while Pepys himself sailed in another ship that weathered a gale and passed the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall on 30 March, five days before the Schiedam was wrecked. Pepys’ direct involvement with the ship begins then – once back in London he concerned himself with the court-martial of the Schiedam’s captain and with the disposal of salvage. Among the letters in the National Archives regarding the Schiedam are several signed by Pepys and Charles II, a remarkable testament to the involvement in this story of two of the most significant figures of the age.

Samuel Pepys circa 1690, some six years after his return from Tangier (attributed to John Riley, National Portrait Gallery, London, reproduced here under License).

Pepys’ role in English Tangier has been the subject of extensive scholarly appraisal (Routh 1912; Lincoln 2014). His involvement began twenty-two years before the evacuation when he was appointed to the Tangier Committee, set up to oversee the new English garrison after the town had been handed over by the Portuguese as part of the dowry of King Charles’ wife Catherine of Braganza. At the time, there were high hopes for Tangier as a trading port – in his diary entry of 28 September 1663 Pepys wrote that it was ‘likely to be the most considerable place the King of England hath in the world’. As Treasurer of the Committee he profited personally from the enterprise, describing it as ‘one of the best flowers in my garden’ (26 September 1664), by taking presents from merchants vying to supply the garrison and from those to whom he had awarded contracts. However, it soon became clear that all was not well in Tangier. There was corruption in the governance, and the town failed to attract the type of entrepreneurs who were needed. It developed a reputation for debauchery and vice; by 1667 Pepys was calling it ‘that wicked place.’ The Great Fire of London, the plague and the Anglo-Dutch war meant that there was little money available to invest in it, a particular problem because of the huge cost of building the ‘Mole’ or breakwater that was thought necessary to create a protected anchorage. Moreover, it was under constant threat of Moorish attack, culminating in the great siege of 1680 – an event that made many realise the impossibility of defending the city in the long term without a greatly strengthened garrison, something for which there was little political will.

Another factor which may have sealed the fate of Tangier – as it nearly did Pepys – was the ‘Popish Plot’ of 1678-81, a fictitious but widely believed conspiracy to usurp the throne and replace Charles with a Catholic king. Pepys’ enemies tried to prove that he favoured Catholics, resulting in him losing his position as Secretary to the Admiralty and being imprisoned in the Tower of London accused of treason and piracy. The charges were soon dropped, but as the case never went to trial he was unable officially to clear his name. Tangier had come under suspicion as a possible Catholic stronghold because several of its governors had been Catholics and many of its garrison were soldiers of Irish Catholic origin. At the time of his appointment in 1683 as counsellor to Lord Dartmouth – who had been put in charge of the Tangier evacuation – Pepys was still under a cloud, and eager to regain his former position. This helps to explain the fervour with which he approached the task and his strong support for Dartmouth and the King in their decision to abandon Tangier.

While at sea Pepys started a new diary that is the main source of information about the final months of the English occupation. The Tangier Diary differs from his more famous diary of the 1660s because it is mainly a record of events and observations at a time when his career was in question, but the entries as well as his letters of the period still have touches of his exuberance and humour. Having boarded the Grafton in Portsmouth for the voyage, Pepys wrote to his fellow-diarist John Evelyn on 7 August 1683 that ‘I shall goe in a good ship, with a good fleete under a very worthy leader, in a Conversation as delightful as companions of the first form in Divinity, Law Physick, and the usefullest parts of Mathematics can render it, namely Dr Ken, Dr Trumbull, Dr Lawrence, and Mr Shere; with the additionall pleasure of concerts (much above the ordinary) of Voices, Flutes and Violins.’ ‘Mr Shere’ was Henry Shere, a major figure in the story of Tangier as he was the engineer who largely designed the Mole, and then had the unhappy task of supervising its destruction. Once at Tangier – where he carried out a risky reconnaissance outside the walls, close to the Moor encampments – Pepys kept up a considerable correspondence, writing on 14 October to his friend the merchant James Houblin in London that ‘Our sulphurmongers are preparing a doomsday for this unfortunate place.’

It is unclear whether Pepys would have known the Schiedam’s final captain, Gregory Fish, when they were in Tangier, but he certainly came to know of him in June 1684 back in London when Fish went on trial for negligence in losing the ship. Fish’s competence had been called into question in a letter from Colonel Kirke, the last Governor of Tangier, to Lord Dartmouth, on Kirke’s arrival at Pendennis Castle in Falmouth on 7 April, only three days after the wrecking (Dartmouth 1887-96: 115):

… Mr Fish lies abed and cries instead of saving any of the wreck, and if he would have promised the country people to pay them they would have saved the horses, for they stood but up to the belly in water for six hours; in short he is a greater beast than any of them, and as the lieutenant tells me knew now where he was, though he met a Dutch vessel that told him how the land bore, and his course was directly on it, he believed himself upon the coast of France, and so came ashore before he saw it. The lieutenant asked him why he would undertake to command a ship and understand it no better; he said that he was sorry for it and was against it himself, but was over persuaded to take it …

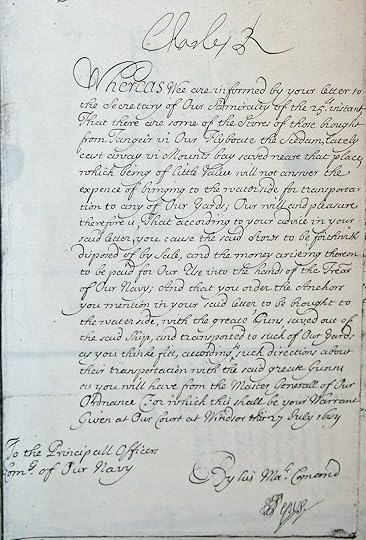

Letter from King Charles II regarding the Schiedam, signed by the King and by Pepys (The National Archives, ADM 106/58/6).

The outcome of the trial is revealed in one of the most informative documents concerning the Schiedam, signed by King Charles II and Pepys (ADM 106/58):

Charles R

Our will and pleasure is, That you cause Bills to be forthwith made out, and paid by the Treasurer of Our Navy for an allowance of Salary to Mr Gregory Fish, for the time it shal appeare to you, he officiated the Office of Master Attendant, for the Affaires of Our navy at Tanger … and forasmuch as Our Right Trusty and welbeloved Conceller George Lord Dartmouth, did commit the charge of bringing home the Scedam Flyboate, a prize taken by one of Our Ships from the Pirates of Sally, and employed for the transporting the Materialls and Stores, then belonging to the Service of Our Mole att Tanger, to the care and direction of the aforesaid Gregory Fish; Our further will and pleasure is, That in Satisfaction for his endeavours therein, (he having passed a Tryall, and being acquitted by a court Martiall, for any blame about the loss of Our Said Ship, upon our Coast of England in her returne home), you also cause Bills to be made out to him, and paid by the Treasurer of Our Navy, for an allowance of Wages, equal to that given by us, according to the Customs of our Navy, to the Comanders of Our Ships of the Sixth Rate, for the time which it shal appeare to you, he served in the Said Ship. For which this shal be your Warrant. Given att Our Court att Windsor this 30th June 1664.

To the Principall Officers and Commanders of Our Navy

By his Majesty’s Command

Samuel Pepys

Fish was acquitted probably because he had been appointed to the command by Lord Dartmouth, whose judgement would have been in question had there been a guilty verdict, and despite the fact that the horses – the only casualties of the wreck – were Lord Dartmouth’s personal property. Undoubtedly there would also have been a general impetus to resolve speedily and with minimal fuss the affairs of Tangier, something to which Pepys would have been party. Nevertheless, it seems clear that Fish, formerly ‘Master Attendant for the affairs of the Navy at Tangier’ with little seafaring experience, was ill-suited to the command – so Pepys would have seen him, and the wrecking, as a salutary example of the consequence of appointing inexperienced commanders that was later to be one of his main criticisms of the Navy, and a focus of reform.

Among the other matters dealt with by Pepys’ office was a petition of June 1684 by Henry Dale, ‘late Master Caulker at Tangier and Gibraltar on behalf of himself and six other Caulkers’ ‘ … returning to England on the Schiedam Prize, were on the 4th of April 1684 Cast away in Mount’s Bay by distresse of weather, to their very great detriment, they having not only lost their Clothes, Tooles, and other things then on Board, but had their wages abated …’ (ADM 106/58).

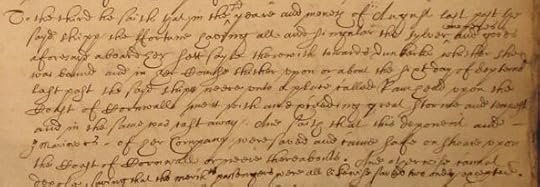

By far the greatest concern, though, was the question of material salvaged from the wreck, the subject of eight of the ten letters in the Admiralty Papers signed by or received by Pepys regarding the Schiedam. Had the ship been a private merchantman her salvage would have been of no official concern to him, but as Secretary to the Admiralty he was responsible for the recovery of naval property which comprised both the ship itself and some of the stores brought as cargo from Tangier. Mr Richard Sampson of Gunwalloe, who had salvaged much material in the days following the wreck, presented a claim ‘For the Honourable Samuel Pepys Esq his Majesty’s Secretary for the Admiralty’, ‘For saveing and securing of Masts Yards Beams Anchors Cables of his Majesty’s Flyboat the Schiedam cast away in Mount’s Bay near the Parish Church of Gunwalloe in the County of Cornwall on the 4th Day of April in the year of Our Lord God 1684’ (ADM 1/3554). The King was also apprised of the matter, having signed a letter regarding ‘the Stores brought from Tangier in our Flyboate the Scedam (sic), lately cast away in Mount’s Bay saved near that place’ (ADM 106/58/6). The following two letters are in Pepys’ own hand (ADM 108/58/10 and 60/2):

My Lord and Gentleman,

Letter from Samuel Pepys regarding the Schiedam, 16 January 1685 (The National Archives, ADM/106/60).

Having procured his Majesty’s warrant to the Master of Ordnance, in pursuance of your desire therein, in your letter to me of the 25th July, for his takeing care to being the Anchors from Mount’s bay, which were saved out of the Scedam lately cast away there, with some other stores belonging to his Office which were also saved at the same time, and to be brought unto the River, My Lord Dartmouth has been pleased to acquaint me that the said Anchors are ordered by him to be brought with the stores belonging to his Office, to Portsmouth, and there delivered by Mr Richard Beach’s order; which I intimate to you, that you may please accordingly to give advice of it to said Richard Beach.

I objure with you mention of those charges attending the salvage of the aforesaid Goodes, but because you doe not deliver your opinion whether the same be reasonable and fit to be allowed to Mr Sampson, I shall forebear moving his Majesty in it, till I receive from you such your opinion, and then I shall, and give you his Majesty’s own directions in it, remaineing Your most humble servant

Samuel Pepys

Derby House, 7 August 1684

My Lord and Gentleman,

Upon your letter to me of 15 December, I have signified to my Lord Dartmouth, his Majesty’s pleasure for his directing of delivery of the anchors and other stores proper for the service of the Navy, of lately saved out of the Scedam (sic), which have been lately brought from her Wreck to Portsmouth and I doubt not but you will find his Lordship’s order issued therein very speedily. I remain your most humble servant,

Samuel Pepys

16 January 1685

The last of Pepys’ letters concerning the Schiedam, dated 16 April 1685 – and signed by the new king, James II - counts among Pepys’ final words on Tangier, but the experience of dealing with the evacuation of Tangier, both in the detail at which he excelled and also on a wider canvas, continued to shape his thinking and career. His part in bringing English Tangier to a conclusion had led to his reinstatement as Secretary to the Admiralty, which allowed him to address deficiencies in naval organisation, discipline and other matters that he had noted during the expedition, something that lets us see English Tangier not as an isolated and rather odd episode in British history but rather as a stepping stone to British naval hegemony and imperial expansion in the years to come.

Note

For an account of three unique Portuguese merchant’s weights of probable early 16th century date from the wreck of the Schiedam, see Gibbins 2020. Frequent updates on our discoveries on wrecks off the Lizard Peninsula can be found on our Facebook page Cornwall Maritime Archaeology.

References

ADM: The Admiralty Papers, The National Archives

The Dartmouth Papers, Staffordshire Records Office

Chappell, Edwin (ed.), 1935. The Tangier Papers of Samuel Pepys. The Navy Records Society.

Dartmouth 1887-96: Royal Commission on Historic Manuscripts, 1887-96, The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Davis, Lieut.-Col. J., 1887. The History of the Second Queen’s Royal Regiment. Vol. 1: The English Occupation of Tangiers from 1661 to 1684. London: Richard Bentley & Son.

De la Bédoyère, G. (ed.), 2006. The letters of Samuel Pepys. Woodbridge.

Gibbins, David, 2020. Three Portuguese merchant’s weights of probable early 16th century date from the wreck of the Schiedam (1684), Gunwalloe, Cornwall, UK. www.davidgibbins.com

Latham, R.C. and Matthews, W. (eds), 1970-83. The Diary of Samuel Pepys: a new and complete transcription. London: Bell.

Lincoln, Margarette, 2014. Samuel Pepys and Tangier, 1662-1684. Huntingdon Library Quarterly 77.4: 417-34

Routh, E., 1912. Tangier, England’s Lost Atlantic Outpost. London: John Murray.

April 8, 2020

A Merchant Navy gun crew in action, Part 2: Convoy FS.12, Methil to Hull, 15-17 February 1941

Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins, second left, Second Officer and Gunnery Officer of SS Clan Murdoch from 1939 to 1941, with his gun crew on the ship. The other men are ship’s officers with the exception of the Royal Marine at the rear. The gun is a Quick-Fire 12-pounder on a High Angle mount. For more on this gun see Part 1 of this blog (Photo: Collection of Captain L.W. Gibbins).

Several years ago I wrote a blog about this photo of my grandfather Captain Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins with his gun crew on SS Clan Murdoch in 1940-1. He told me that he had been in action with this gun against German aircraft that machine-gunned and bombed his ship off north-east England early in 1941, towards the end of a long voyage recounted in the Clan Line history In Danger’s Hour in which the ship had also encountered a surface raider. I was able to pinpoint the date of the air attack from the Ship Movement Card, which records that Clan Murdoch was ‘damaged by aircraft’ on 17 February 1941 off the Humber Estuary following a short but dangerous convoy from Methil Roads on the Forth of Firth. Since then I’ve developed a more detailed picture of that convoy and the circumstances of the attack, and rather than add them to the existing blog I’ve extracted the section on the convoy in that blog and edited it into this new one, and called it ‘Part 2.’ The first blog is now mainly about the gun and its operation. The present blog is a work-in-progress, as I have not yet been able to see the Convoy Commodore’s report in the National Archives and would expect that to add significantly to this account. My sources are primary where possible, in particular the Ship Movement Cards in the UK National Archives, but include Arnold Hague’s Convoy Database as well as collations of U-Boat and E-Boat operations.

SS Clan Murdoch (5,930 grt), taken before the war. My grandfather Captain Lawrance Wilfred Gibbins was her 4th Officer in 1929-30 and 2nd Officer from 1937 to 1941, and her Gunnery Officer from 1939-41. The gun in the photo above would have been mounted in the bow. She was launched in 1919 on the Clyde and spent twenty years plying the Clan Line’s main routes to Africa and India before being requisitioned by the Ministry of War Transport in 1940. She was considered something of a charmed ship, surviving many near-misses - in February 1942 while carrying 1,000 tons of bombs to Rangoon a Japanese torpedo missed her by 150 yards, and two months later she survived the Japanese aerial attack on Colombo in Ceylon - but she finally did sink in 1953 off Portugal when under new ownership, having been sold first to the South American Steam Navigation Co in 1948, renamed Halesias, and then to a Panama registered company in 1952, renamed Jan Kiki, when her cargo of phosphate shifted and she capsized. This photo shows her in her pre-war Clan Line livery, which was painted over with wartime grey in 1939 (source: Clan Line: Illustrated Fleet History)(Photo: Collection of Captain L.W. Gibbins).

The Clan Murdoch had undertaken a five-month voyage to ports in India and Africa, having left Liverpool on 4 August 1940 in Convoy OB.193 and been to Cape Town, Durban, Colombo, Trincomalee, Madras, Vizigapatam, Calcutta and Chittagong, and returning by the same route. On 10 January 1941 she joined Convoy SL.62 in Freetown for Liverpool with a cargo of pig iron. On 30-31 January the convoy lost three ships in the space of 24 hours to air attack off Ireland – the Belgian Olympier, the Norwegian Austvard, from which there were only 8 survivors, and the British Rowanbank, lost with her entire crew of 68 British officers and Lascar ratings. Two days after that Clan Murdoch arrived on the Clyde, and a week later she set off in Convoy WN.83 around Scotland towards Methil.

Three of the other ships in that convoy were the Coryton, the Scottish Trader and the tanker the Virgilia, all of them also at the end of Atlantic voyages – the Coryton having left Halifax in Nova Scotia with a cargo of grain on 22 January in Convoy SC.20, which lost five ships to U-Boat attacks. Once at Methil they joined the Norwegian Vigrid and the collier Daphne II to form Convoy FS.12, Phase 5 (named thus as the FS convoys were numbered 1-100 in repeating phases). The Daphne II carried the convoy commodore, Commander W.J. Rice, R.D., R.N.R. The FS convoys ran from Methil to Southend on the Thames and were the main conduit for goods from the Atlantic convoys destined for ports in eastern England and London. The route was close inshore and was protected by minefields and by aerial cover, but the ships were vulnerable to U-boat, E-boat and aerial attack, including mines laid from the air, and many ships in these convoys were sunk or damaged. They were also open to attack from German aircraft returning from bombing raids on Hull, Newcastle and other coastal targets adjacent to this route.

The convoy set out from Methil on Saturday 15 February. Fortunately, poor weather that day prevented the German E-boats from leaving port; they normally patrolled close to the edge of the British minefields waiting for the southward (FS) and northward (FN) convoys. However, the incident reports for the north-east of England show that the coast from Berwick to Hull was under aerial attack that night, with bombers and minelayers ‘coming over in waves’ and being met with intensive anti-aircraft fire, amounting to several thousand heavy AA rounds. Considerable damage and casualties were caused in Northumberland and especially in South Shields, where one Heinkel 111 (6/KG-4) was brought down by AA fire. At least 45 aircraft are thought to have been involved in this attack on the north-east that night, many of them dropped mines between St Abbs Head close to Methil and Flamborough Head off Hull some 180 miles to the south.

It seems likely that these bombers or their fighter escorts were the aircraft that machine-gunned and bombed the convoy that evening several miles north-east of the Farne Islands. The Coryton was badly damaged, and her master, Captain J.R. Evans, decided to run her aground just south of Lindisfarne, ‘Holy Island’. The report of the Royal National Lifeboat Institute provided a detailed account:

Captain Josiah Raymond Evans, aged 48, received his in 1914 and was also an officer in the Royal Naval Reserve. He received the War Medal and Mercantile Marine Medal for service at sea during the First World War and his family claimed his Second World War medals (the 1939-45 Star, the War Medal and the Atlantic Star). He is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission though not on the Tower Hill Merchant Navy Memorial, as his body was recovered.

SS Coryton (4,553 grt), launched in 1928 at West Hartlepool for John Cory and Sons, Cardiff. By the time of her sinking she had taken part in 18 convoys during the war, including crossing the Atlantic four times from Halifax (Photo: Leslie W. Hansen. National Museum of Wales Collection).

The Clan Murdoch’s Ship Movement Card showed that she reached the Humber Estuary on the 16th, and that she was ‘damaged by aircraft’ on the 17th. The incident reports for that night note that ‘approximately 90 aircraft were employed in minelaying activity off Flamborough Head and further southwards’, the head being at the mouth of the Humber Estuary (the note of damage was not written on the Card until 7 March on her arrival back on the Clyde, where she underwent repairs, so it is possible that the recording clerk got the date wrong and in fact it refers to the action in which the Coryton was damaged, on 15 February). The Card for the Scottish Trader shows that she was under repair at London on 27 February and at Newcastle on 27 March, so she too may have been damaged in these attacks. The Clan Murdoch left the Humber on the 19th for Methil and did not finally depart from there until 4 March, as part of Convoy EN.81 bound for the Clyde. During this period the E-boats became active again, with S102 attacking Convoy FN.11 on 19 February and sinking the Algarve with all hands, and German bombing and minelaying activity continuing on a daily basis.

The Ship Movement Card for Clan Murdoch in February-March 1941, noting that she was ‘Damaged by Aircraft’ on 17 February (National Archives).

The Clan Murdoch was the only ship in Convoy FS.12 not to be sunk in 1941; more than half of the men in that convoy did not survive to the end of that year. Daphne II was torpedoed by E-boat S-102 on 18 March while accompanying the return convoy FN.34, sinking off the Humber though fortunately with no loss of life. Vigrid was torpedoed on 24 June by U-371 some 400 miles south-east of Greenland; the master, 33 crew, 3 gunners and ten passengers (American Red Cross nurses) abandoned ship in four boats, two of which were never heard of again and the other two picked up on 8 July and 13 July, with 21 survivors. Virgilia was torpedoed and her fuel oil cargo set alight on 24 November by S-109 off Great Yarmouth, with 23 of her 44 crew perishing in the flames, and Scottish Trader was sunk on 6 December by U-131 some 300 miles south of Iceland. She was a straggler from Convoy SC-56, and zigzagged in an attempt to avoid the six torpedoes that were fired at her. There were no survivors from her 43 crew.

The Coryton’s Ship Movement Card records salvage attempts in August-September 1941, when a survey indicated that the forward end might be refloated, but all attempts were abandoned after heavy seas caused both ends to collapse. Today the wreckage lies partly buried in sand and shale a few hundred metres off Ross Sands in Budle Bay, with the boilers standing proud of the seabed and other structure visible. A photo of the wreck taken soon after her grounding can be seen here, as well as photos of the site underwater in this 2007 report by the Tyneside branch of the British Sub-Aqua Club.

March 26, 2020

The wreck of the Fortune (1653), off Rame Head, Cornwall, England

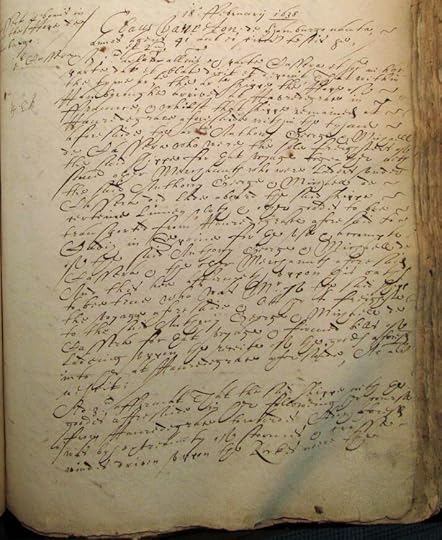

The first page (fol. 35) of the deposition in the High Court of Admiralty manuscripts HCA 13/68 regarding the wreck of the Hamburg ship the Fortune off Cornwall. The name of the captain and the ship can be seen in the first sentence upper right and the date of the deposition at the top. The scan is reproduced from the Marinelives website.

Following on from my last blog, the Marinelives project has revealed another previously unknown shipwreck off Cornwall among the High Court of Admiralty (HCA) manuscripts of 1627-77 held in the National Archives at Kew. In this case the location of the wreck is more precisely recorded, leading to the possibility that it may one day be found. Of particular interest is the richness of the cargo, including a silver ingot and many pieces of eight, and the fact that she was bringing goods largely procured from the Spanish New World. The following extracts are from a transcription made by Colin Greenwood in 2013 of more than 3,700 words related to the wreck in HCA 13/68, a volume of witness statements (depositions) to the High Court of the Admiralty in 1653-4. The extracts here retain his spellings and punctuation (for his complete transcription, go here).

The deposition (HCA 13/68, folios 35-7) was made on 8 October 1653 by several ‘merchants of Spayne and subjects of the King of Spayne for their goods lately laden on att the Island of Palma in the Canaries and Cast on shoare in the ship the ffortune whereof Phillip Duncar was Master upon the Coast of Cornwall.’ Their intention was to show that the goods were Spanish rather than Dutch, an issue at the time of the first Anglo-Dutch War (1652-4). The merchants included Joseph Markes (probably Marques), John (Juan) Baptista Margarita (also spelled Mogarita and Magherrita), Pedro (Petro) Soramo (Soranno, Saranno, Sararma) of Seville, Juan and Diego de Valetta of Dunkirk and Palma, John (Juan) Sallazar (Salazar) of Palma, Antonio Riche (or Reg(los?)), Don Juan de Monteverde and Juan Gomez Brito. Of these men, ‘El capitan’ Don Juan de Monteverde was a regidor (councillor) at La Palma in 1669, and Juan Gomez Brito is almost certainly the captain of that name who was wrecked in his ‘frigate’ La Gallardino off the coast of Cuba in 1660.

The first statement in the deposition was by the ship’s master, Philippe Doncker (here spelled Dunker or Danker), ‘aged four and twenty years or thereabouts’, ‘of Antwerp in Brabant Captaine or Commander of the sayd ship the ffortune’, which he had bought ‘for ready moneyes a yeare ago at Hamburg.’ A biography by a descendant shows that Philippe, who also styled himself ‘Doncker de Formestraux’, was probably born in Lille in France in 1629, the son of a prominent Antwerp merchant named Louis Doncker and his wife Marguerite de Formestraux.

A closeup of the second page of the deposition in the High Court of Admiralty manuscripts HCA 13/68 regarding the wreck of the Hamburg ship the Fortune off Cornwall. The word ‘Ramhead’ can be seen fifth line down. The scan is reproduced from the Marinelives website.

Having begun her outward voyage at Dunkirk in May 1653 and being ‘att or near the Island of Palma’ in August, the merchants in Palma ‘did Lade and putt on board the sayd ship, in addition to several barrels of ‘Tortle shells’,

… three thousand and seven hundred hides or thereabouts, one large barr of sylver the certayne value whereof he knoweth not, and a good quantity of moneyes in pieces of 8/8 but how much in certaine he knoweth not, four barrells of Spanish Tabacco, a great quantity of dry ginger loose and about four barrells and one Potaco more of Varinaes Tobacco, and forty Ratacos more of varinases tabaccoes, thirteen pipes of sugar or thereabouts, eighteene baggs of ginger, a great quantity of Brazil and Camp[?o]cha wood …