David Gibbins's Blog, page 6

June 24, 2015

Private John F. Lofts, Military Medal, 9th Queen's Royal Lancers 1915-1919

Unnamed photo of First World War date presumed to show six men of the 9th Lancers, including Private John F. Lofts (photographer unknown, but stamped as a postcard on reverse).

I have a considerable family connection with the 9th Lancers, one of the most historically interesting of the British cavalry regiments – my maternal grandfather Tom Verrinder and his brother Edgar served with the regiment during the First World War, and on my father’s side my great-great uncle Major Edward Robertson Gordon was with the regiment during the Boer War, commanding it briefly in 1901 (and co-authoring the Diary of the 9th (Q.R.) Lancers during the South African Campaign, 1899-1902). Edward's uncle William Cracroft Gordon was an officer with the regiment in India during the 1850s, as was his nephew John Gordon in Italy towards the end of the Second World War.

While researching these men I acquired a fine copy of the regimental history, The 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers 1715-1936 by Major E.W. Sheppard (Gale and Polden, 1939), signed ‘J.F. Lofts’ and accompanied by a First World War era regimental cap badge. Private J.F. Lofts is mentioned in the book for receiving the Military Medal - a gallantry award for enlisted men - following the regiment's involvement in repelling the German Somme offensive in Spring 1918; the award is also noted in the regiment's War Diary, seen in the image below, in the gallantry award medal index card in the UK National Archives (WO 372/23) and in the London Gazette for 16 July 1918. The National Archives also hold his Medal Card for his three campaign medals, showing that his name was John and noting that he arrived in France on 1 June 1915 and was discharged to the army reserve on 6 May 1919.

Taped into the front cover of the book was the photo reproduced above, showing six men inside a stable block, one of them (not the Lance-Corporal) presumably Private Lofts. Because the building is a permanent stable block this photo is most likely to have been taken during his period of cavalry training in England, probably at Tidworth in Wiltshire, the main cavalry training depot, prior to his departure to France in mid-1915. My grandfather’s training during the following year took place over a five-month period at Tidworth, and included much focus on grooming and looking after horses as depicted in this photo.

The period of action for which Lofts received his M.M., during the German Somme offensive in March-April 1918, is described at length in the regimental history as well as the 9th Lancers’ War Diary. From the start of the offensive on 21 March until the tide was turned in early April the regiment was continuously involved in front-line action, a period my grandfather remembered for the Germans coming in their thousands as ‘point-blank targets.’ The specific circumstances of Lofts’ award are unknown, but he was one of eight men of the regiment to be decorated after the battle, ‘no more – perhaps somewhat less – than its deserts,’ according Major Shepperd in the regimental history. The regiment lost 33% of its fighting strength during the battle including 58 men killed, the largest loss during one battle among the 296 men of the regiment recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as being killed during the war.

The London Gazette citation, shown below, notes Private Lofts's home town as Bury St Edmunds, meaning that he is very probably the John F. Lofts listed in the 1901 Census as the nine-year old son of Emma J. and Robert Lofts, a house decorator of that town. The Births, Marriages and Deaths Index lists a John Francis Lofts as born in the fourth quarter of 1891 in Bury St Edmunds, and the England and Wales Death Index for October 1974 includes a John Francis Lofts of Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, who was born on 10 October 1891. The 1911 Census shows a John Francis Lofts of the right age as a bank clerk in Cambridge, and Kelly's Directory shows a man of that name living in Bishop's Stortford by 1926. All of these references can be found by searching his name on ancestry.co.uk.

Entry in the 9th Lancers War Diary of 25 April 1918 showing the award of the Military Medal to Private J.F. Lofts (UK National Archives, WO 95/1113/2).

Medal Card of Private J.F. Lofts showing the award of the three campaign medals (Victory Medal, War Medal and 1915 Star), his date of first arrival in France of 1 June 1915 and his transfer to army reserve ('Class Z') on 6 May 1919 (UK National Archives, WO 372/23/134514).

An image from the London Gazette of 16 July 1918 showing 6876 Pte J.F. Lofts in the list of Military Medal recipients, and showing his home town as Bury St. Edmunds.

May 30, 2015

The Rumpa Rebellion, India, 1879-80: jungle fever and the cause of malaria

This is one of several postings related to the 1879-80 Rumpa Rebellion in India, a setting in my novel The Tiger Warrior that I researched extensively using primary sources in the India Office Collections of the British Library. The rebellion was a tribal uprising in the jungle of southern India near the Godavari river, and was countered by a brigade-sized expedition of the Madras army including a company of sappers led by my ancestor Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers. For my other postings, on human sacrifice and counter-insurgency in the jungle, click here. Once these postings are complete a comprehensive account of the rebellion and the British military deployment with full references will be added as a PDF.

A view of the jungle near Rumpa from the Godavari river. The problem with mosquitoes, especially during the monsoon, can easily be envisaged.

The greatest challenge facing the regimental surgeons with the Rumpa Field Force in India in 1879 was jungle fever, ‘that severe sickness that paralyses every effort, disheartens the men, and fosters the preconceived belief of the superiority and valour of the insurgents.’ The Madras Military Proceedings for 1879 and 1880, the source of this quote and others below, reveals a stark picture. As with many campaigns of the Victorian period, including the 1878-81 war in Afghanistan, death and disability through illness far outstripped the casualties of battle. The pestilential nature of the upper Godavari region was notorious well before the rebellion. Sixty years earlier, in the summer of 1819, fever had struck down all of the men of the Great Trigonometrical Survey sent to map the district, under Lieutenant George Everest of the Bengal Artillery. They were deep in the jangal, the Hindi word for uncultivated land that the British used for dense rain forest. Because of the ‘champagne quality’ of the air after the rains, essential for theodolite sightings, they had been working through the summer months when the monsoon reduced the jungle to a quagmire and the air was thick with mosquitoes – something they had yet to connect with the illness.

Everest survived to see his name immortalized in the Himalayas, but fifteen of his party died and much of the region was bypassed. In 1879 it remained largely unmapped, a vast area of jungle and hills as poorly known and forbidding as any territory beyond the frontiers of India. Deep-seated fear of illness among the British can be seen as one of the main factors behind the 1879 rebellion, as it was the reluctance of the British district officials to live in the hills that led to the unchecked corruption of the local headman and the native police constables that was a major grievance of the rebel leaders.

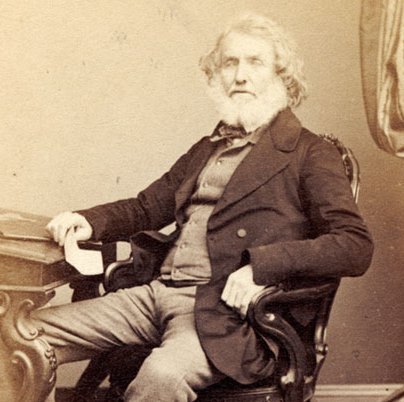

Colonel Sir George Everest, who as a young officer working for the Great Trigonometrical Survey was one of the first Europeans to explore the Godavari jungle, in 1819.

The huge toll taken by illness on Rumpa Field Force is shown by the medical report on the 10th Madras Native Infantry (later the 10th Gurkha Rifles) after 8 months of deployment:

… the whole regiment has suffered, and is still suffering, from malarious fever. Most of the men have had repeated attacks, and are in a very debilitated state, needing rest and an early removal to a more favourable climate … In many instances the fever has been followed by serious after-consequences, such as enlarged spleen, anaemia, partial paralysis, extreme emaciation, disorders of the stomach and bowels, and other complaints of a grave nature … many of the men were actually passing through the hot stage of a febrile paroxysm, and their sufferings and distress were painful to witness.

All of the British officers in the regiment and three-fifths of the sepoys were unfit for duty, amounting to 303 out of 505 men. The deaths from fever in that regiment alone amounted to 24, including one European, Major W.C. Bayley, who died on 17 January 1880 of ‘conjestion of the brain’ – probably cerebral malaria; his gravestone near the village of Rumpa, ‘erected by his fellow officers,’ was to be one of few lasting reminders of the army deployment in the district.

Considerable effort was made to provide medical personnel for the units deployed. The surgeon who accompanied the Madras Sappers in 1879 was Dr George Lemon Walker, a Canadian born in Kingston, Ontario, who had trained at Queen’s University, Belfast before making a career in the Indian Medical Service. Because the sapper companies were despatched to Rumpa at very short notice that August they had arrived without an appropriate complement of medical servants, but they were then provided in the same proportion as for the Madras Sappers in Afghanistan – a sweeper, a waterman, a coolie and a ward coolie for each company – after the direct intervention of the Madras Surgeon-General:

… in ordinary native regiments in serious cases orderlies are detailed to attend on the sick and assist them in various ways, but I consider that the services of the Sapper in the field are much too valuable to be diverted in this manner … It may also be mentioned that orderly duty is particularly distasteful to the Sapper.

Nevertheless, without a full understanding of the connection between malaria and mosquitoes, even this provision of extra orderlies could do nothing to allay the problem of disease in the jungle; by the end almost all of the sapper officers had been invalided out of Rumpa through illness. The medical report on the Madras Army for 1880 shows a spike in deaths directly attributed by the medical authorities to the Rumpa deployment, with almost 400 native troops dying of disease that year. The troops were not the only ones stricken: Octavius Butler Irvine, Acting Collector and Magistrate for Vizagapatam, a district that included part of the hill tracts, died of fever in the jungle on 14 March 1880 while he was attached to the Field Force.

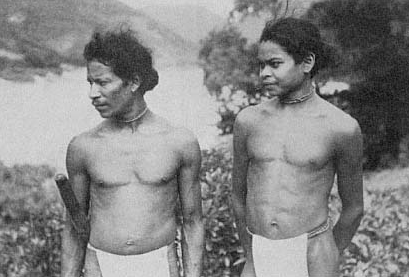

Tribal people such as these Hill Reddis on the banks of the Godavari may have had some resistance to malaria, as well as their own treatments (photo: Christoph von Furer-Haimendorf, Tribes of India).

The cause of all this misery, ‘jungle fever’, the same illness that had laid low Lieutenant Everest and his survey team sixty year before, was a particularly virulent form of malaria. By a remarkable coincidence the man who was to have the greatest impact on the understanding of malaria was on the Madras medical establishment while cases from Rumpa were being treated. In 1883 the recently qualified Acting Garrison Surgeon at Bangalore, and a year later the officer in medical charge of the Madras Sappers, was Ronald Ross – later Sir Ronald Ross, Nobel laureate and Fellow of the Royal Society, famous for establishing that the Anopheles mosquito was the carrier of the malaria parasite.

In 1882 Ross had been in medical charge of the 10th Madras Native Infantry, whose sufferings two years earlier in Rumpa are described above. In his autobiography, Ross writes warmly of his time with the Madras Sappers in Bangalore, where he shared a bungalow with fellow officers. He would undoubtedly have treated Rumpa veterans suffering from remittent malaria, several of whom were affected for the rest of their lives – including Captain Robert Ewen Hamilton, officer in command during the engagement at Rekapalle described in my previous post, who died in 1885 from cholera, his health ‘shattered by continued attacks of malarial fever’ picked up in Rumpa, and Colonel Robert Wauchope, his health broken by malaria and forced to early retirement in 1900. Treating these men may well have spurred Ross to his most important realisation, that he was going to have to make visits to the jungle of the eastern Ghats himself to collect mosquitoes in order to test his hypothesis.

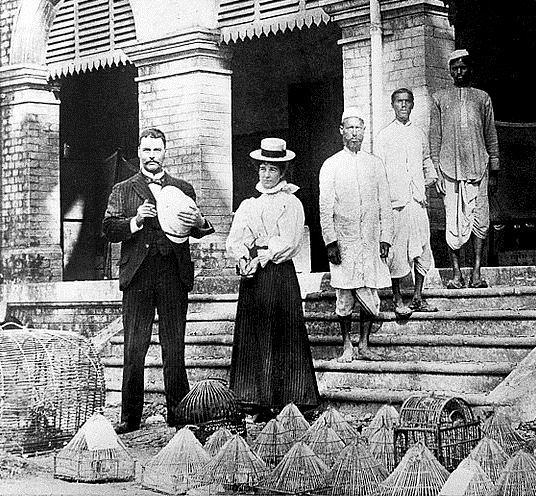

Surgeon-Major Ross with his wife and assistants outside the Calcutta laboratory where he carried out his research, photographed in 1898.

Quinine was available by the time of the Rumpa rebellion, but it was only in 1880 that the malaria parasite was identified – by Alphonse Laveran, a French army surgeon – and not until 1897 that Ross announced his breakthrough in identifying the Anopheles mosquito as the culprit. Nevertheless, as early as 1883 he had made the connection between mosquito breeding and standing water, and his greatest effort in later years was to press for improved sanitation and the draining of standing water around settlements in regions where malaria was rife. In 1905, the annual report by Colonel Walter Andrew Gale as Chief Engineer in Baluchistan shows how important the clearance of mosquito-breeding water had become, something that would also have been a prime consideration in the planning of barracks and cantonments by the other sapper veterans of Rumpa who went on to employment in the Public Works Department in India.

Ross also knew that children brought up in infected areas could develop a degree of immunity, as appears to have been the case among the Koya and Reddi hill people - who had their own treatment for the fever, a pill made from paste of the bark of Alsonia scholaris, the root bark of Ophioxylon scrombiculatum and the root, stem and leaves of Andrographis paniculata. This may also have been the case for British officers such as Lieutenant Gale who had been born in India (as was Ross himself); Gale's first years on his father’s indigo estate in Bihar – a region in which mosquito-borne illness was rife - might help to account for his service throughout the Rumpa deployment from August 1879 to early 1881, the only British sapper officer to remain in the field without being invalided through illness.

By adding to Ross’s formative experience and thus helping to alleviate ‘a gigantic amount of misery in the world,’ as Ross described malaria, the suffering of the troops in Rumpa contributed not only to suppressing the rebellion and improving administration in the Godavari hills but also to a scientific and medical advance of huge global significance to this day.

May 29, 2015

The Rumpa Rebellion, India, 1879-80: counter-insurgency in the jungle

In my novel The Tiger Warrior, Lieutenant Howard of the Madras Sappers shoots his way out of a jungle shrine in 1879 using an obsolete 1851 Colt percussion revolver inherited from his father from the time of the Indian Mutiny. This photo shows me shooting the original London-made revolver that was the basis for that scene (photo: Alan Gibbins).

This is the second of several planned postings related to the 1879-80 Rumpa Rebellion in India, a setting in my novel The Tiger Warrior that I researched extensively using primary sources in the India Office Collections of the British Library. The rebellion was a tribal uprising in the jungle of southern India near the Godavari river, and was countered by a brigade-sized expedition of the Madras army including a company of sappers led by my ancestor Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers. For my other postings, on human sacrifice in the jungle and malaria, click here. Once these postings are complete a comprehensive account of the rebellion and the military deployment with full references will be added as a PDF.

The river Godavari close to Rumpa district, showing the extreme difficulties faced by troops chasing rebels during the uprising.

The Military History of the Madras Engineers and Pioneers, published in 1881, contains only a brief account of the involvement of the Madras Sappers and Miners in the Rumpa Rebellion, written by an officer who was not present and at a time when most of the junior officers who had been deployed in the Rumpa Field Force had left the Corps for other appointments. Although service in the Field Force counted as ‘War Service’ in officers’ records, there was to be no campaign medal – the only general service medal then issued in India was awarded sparingly, and only for frontier actions – and therefore little military glory, with the rebellion being overshadowed by the Afghan War of 1878-81 in which most officers of the Corps had served. Nevertheless, unlike the Afghan War, the Rumpa operations were an unqualified success, and the two companies of Madras Sappers deployed in the Field Force –a brigade-sized force ultimately numbering more than 2,500 troops of the Madras army and the neighbouring princely states, as well as police - saw more action than a number of the Madras sapper officers sent in 1880 to Afghanistan, where they spent their time building roads and other installations in the frontier passes without encountering the enemy.

The volumes of the Madras Military Proceedings held in the India Office Collections of the British Library provide a detailed record of all army operations during the Rumpa campaign, based on the daily reports of officers in the field (many of which are reproduced verbatim); the page and date references for the material quoted below will appear in the PDF to accompany these posts. The operations bore many of the hallmarks of a modern counter-insurgency campaign: patrolling for an elusive enemy; short, sharp contacts when they did occur; searching villages for concealed weapons; and reprisals and punishments on both sides. The initial role of the sappers on their deployment in August 1879 was as infantry, relieving parties of the 10th Madras Native Infantry as guards on the river steamers and then in the hills. Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, my ancestor, took a detachment of G Company deep into the jungle to Yellaishweram, where they fortified a camp and confronted the rebels. Lieutenant Robert Ewen Hamilton - recently returned from Afghanistan - with 60 men of D Company was sent above the gorge of the Godavari to prevent rebels crossing into the adjacent princely state of Hyderabad, and to contain the uprising in the neighbouring district of Rekapalle.

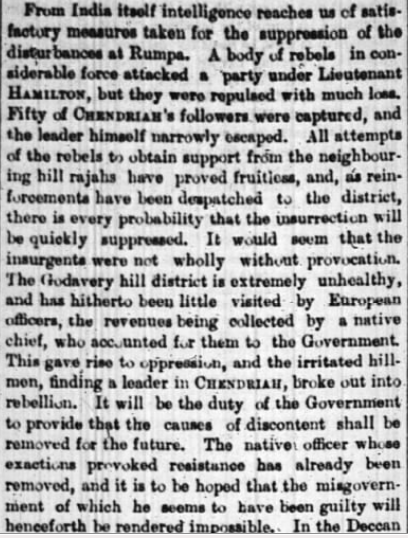

This article from The Times of 1 September 1879 mentions Lieutenant Hamilton's action and shows a sympathetic understanding of one of the rebels' causes, the depredations of the local chief and tax-collector - though it also expresses undue optimism about the conclusion of the rebellion, which was to carry on for another year. Click to enlarge.

On 20 August 1879 Hamilton and his men were involved in one of the bloodiest engagements in the rebellion, one reported in The Times and The New York Times. On the previous day, Hamilton had been informed that one hundred men under the rebel leader Chendriah were eight miles away intent on looting Rekapalle. Along with Mr J.F. Beddy, Assistant Commissioner in the Central Provinces, he marched with 30 sappers through the night and led a dawn attack. Despite surprise being lost at the last moment, the sappers advanced out of the jungle in skirmishing order and met a heavy fire. Hamilton described the action:

The fire of the sappers, however, as they advanced, demoralized the rebels, for they retired into the jungle, keeping up a continuous fire. As the troops advanced, some high cultivation intervened, so they moved along the side of this into the village, then going on arrival on open ground, and kept up a fire on the rebels, who were occasionally visible as they moved through the jungle … where the rebels, knowing their way about, had such a decided advantage on the sappers, without regard to numerical strength … I was, however, wrong in thinking the rebels had retired, for the whole way back they harassed us considerably, keeping up a continuous fire, which was replied to wherever practicable … but the rebels always took refuge behind the trees and it was difficult to get a good shot at them.

After enduring more harassing fire as the rebels ‘flitted from tree to tree’ Hamilton reached Rekapalle, where he halted and repelled the attacks ‘by heavy fire.’ Altogether 1050 rounds were expended from their Snider-Enfield rifles, and ten rebels were killed.

Despite this and other successes, four months later the Adjutant-General in Madras expressed his frustration: ‘Up to the present time, our action has not been such as to instill fear amongst the rebels or confidence amongst those who are well-disposed towards us …our position in the disturbed districts is little, if at all, better than it was ten months ago when the insurrection first commenced. Our troops are uselessly harassed and exposed, suffer in health and in life, and we seem no nearer suppressing the insurrection than in March last.’

A photo of me shooting a breechloading Snider-Enfield rifle of the type used by Lieutenant Hamilton's sappers during the Rumpa rebellion. Colonel Macquiod's Hyderabad troops who took part in the second action described here were still using muzzleloading percussion rifles (photo: Alan Gibbins).

In response to this, the commander of the force, Colonel (acting Brigadier) Lewis William Buck, ordered a surge in offensive patrolling over the next four months, during the dry season. On 15 January 1880 a surprise attack by troops killed six rebels, and the troops confiscated ‘one percussion gun, seven matchlocks and a dagger.’ On 16 February another rebel was shot, and troops recovered ‘two police carbines, one matchlock, a sword and some bows and arrows.’ In another incident a rebel shot and wounded a policeman with an arrow, before cutting his own throat. The rebels continued to mount audacious attacks: on 17 March police repulsed one attack, killing four; two months later another attack resulted in the deaths of four constables. On that occasion Colonel Richard Kirwan Macquoid of the Hyderabad Infantry - an Indian Mutiny veteran - went after the enemy, in an attack he described vividly in his report:

About 8.30 I proceeded on my way to Ponch, preceded by an advance guard. We had not gone more than one and a half miles before a shot was fired by the enemy, followed by five or six others in quick succession. Dr Brown and myself were riding together at the head of the column; we jumped off the horses and got the men into skirmishing order on the right and left of the road and opened fire on the enemy … we quickly drove the enemy from their position and they made for the river which was close by, and, jumping in, swam to the opposite bank. We kept up a hot fire on them as they did so.

Ten rebels were killed and twenty wounded, for the loss of one man killed and one wounded, and a wound to MacQuoid’s horse. Surgeon William Richard Brown - a future Surgeon-General, and official surgeon to the Viceroy - had two months earlier shot and killed the rebel leader Bemma Reddi. In the same month the rebel widely seen to be the ringleader, Chendriah, was murdered by a rival and his head sent to the British, an act that could have ended the rebellion except that by then the rebel force had fragmented into many smaller gangs under their own leaders. It was the surge in offensive patrolling that gradually gave troops the edge, as well as improved tactics and equipment. The number of night engagements led the force commander Colonel Buck to request special ammunition: ‘Frequently the rebels have been surprised at night and got off with very small loss in killed and wounded, and I think that, if the men had buck-shot cartridges, the effect would be greater.’

Click on this jacket image to go to the book page and see all international editions with links to Amazon and other sellers.

The reports reveal the civilian cost of the rebellion, and the brutality. The rebels frequently terrorized and murdered villagers; in one of many incidents, three men were murdered in January 1880 at the village of Pundamamidi by Karum Jumman Dora, a rebel leader. In February, troops and police destroyed the village of Angulpolem for harboring a rebel, and punishments were meted out to others who assisted the enemy. By the middle of 1880 at least 26 rebels had been killed and over 100 had been captured and put on trial. Many were sentenced to short terms in local prisons, and some were transported to the penal colony on the Andaman Islands, but those convicted of murder were hanged. The place of execution, whether in the lowland town of Rajahmundry or in the hill villages, became a matter of contention: ‘ … at present, prisoners sentenced to death are hung at Rajahmundry. Mr Johnson strongly advocates that all Rumpa prisoners convicted of murder and sentenced to death should be hung at Chodavaram … I do not know that this will do much good, as, knowing the native prejudice to attend such occasions, I can hardly expect any large numbers to go to see the executions …’ Despite these measures and the attrition among rebel leaders, it was only the arrival of the monsoon in late 1880 that put a halt to the killings that by then had made the rebellion the most costly in human lives within India since the Mutiny.

May 28, 2015

The Rumpa Rebellion, India, 1879-80: Human sacrifice in the jungle

A woodcut from John Campbell’s A Personal Narrative of Thirteen Years Service amongst the Wild Tribes of Khondistan for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice, published in 1864.

This is the first of several planned postings related to the 1879-80 Rumpa Rebellion in India, a setting in my novel The Tiger Warrior that I researched extensively using primary sources in the India Office Collections of the British Library. The rebellion was a tribal uprising in the jungle of southern India near the river Godavari, and was countered by a brigade-sized expedition of the Madras army including a company of sappers led by my ancestor Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers. For my other postings, on counter-insurgency in the jungle and malaria, click here. Once these postings are complete a comprehensive account of the rebellion and the British military deployment with full references will be added as a PDF.

In my novel The Tiger Warrior, set partly in India during the Victorian period, Lieutenant John Howard of the Madras Sappers takes cover with his men on an armoured river steamer deep in the jungle of southern India, part of a force deployed against a tribal rebellion in the Rumpa district of the eastern Ghats in 1879. As bullets spatter off the metal plating, Howard watches a horrifying ritual unfold among the rebels gathered on the opposite river bank, one that leads him to pick up a rifle and take a course of action that he could never have thought imaginable:

Photo of me shooting a Snider-Enfield rifle of the type that Lieutenant Howard uses in my novel (photo: Alan Gibbins).

A boy, not much older than his own son, was chained to the pole. His head was lolling like the man’s, but his body shuddered, still alive. Four of the women held out his little arms and legs. The man in the tiger skin approached, and took up a smaller pole, like the handle of an axe. He tapped the boy on the head with it, and then tapped each of the boy’s limbs. Only they were not taps. Howard had been seeing everything in slow motion, and as his mind replayed it, he saw the little limbs each crack and flop away, broken like boughs of dry wood. The women let go, and the small body hung like a rag doll from the chain that held his neck. A rope tied to the top of the pole was pulled, and the cock began to whirl round and round, followed by the women, who circled it. Among the swirling robes there were flashes of blades held in readiness, glinting. The boy raised his head, and Howard was sure he heard crying, the helpless crying of a child that seemed to reach out to him, that seemed to come from a child of his own. It was unbearable.

The fictional Lieutenant Howard is closely based on an ancestor of mine who served in the rebellion – Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale of the Madras Sappers, pictured below – and the incident is inspired by actual accounts of ritualized killing carried out by the rebels. The 1908 Imperial Gazeteer of India reports ‘strong reasons for believing’ that two men were sacrificed at Dummagudem near Rumpa in 1876, and that men were ‘openly sacrificed’ during the Rumpa rebellion. First-hand accounts of ritualized killings are found in the reports of the Madras Judicial Proceedings in the India Office collection of the British Library. In March 1879, the rebel leader Tamman Dora took his police captives to a sacred place where he beheaded two of them with a sword in the presence of several hundred tribesmen. The killing was allegedly a ritual sacrifice in honour of Melveri, a goddess ‘very partial to human victims’. In September of that year, the sacrifice of a villager was recounted by a native eyewitness (reported in the Proceedings, 8 March 1880):

Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers, one of a small number of British officers involved in the 1879-80 Rumpa expedition who may have witnessed evidence of human sacrifice first-hand.

They sacrificed him to Gudapu Mavili. They made him sit down, then Chendrayya struck him with his sword. Zunapalu got up and began to run away; Chendrayya’s people threw stones at him; Zunapalu fell down and then Chendrayya’s men cut off his head.

The police later found the headless body. On 30 March 1880 the Proceedings reported an assault by troops on a village from which thirty rebels escaped, and where they found ‘three pariahs … who said they had been reserved for sacrifice’; they also found the headless body of the village ‘watcher’, ‘sacrificed.’ Another report notes that four pariahs were sacrificed by the rebels on 18 May. These accounts, identifying pariahs, ‘outcasts’ - traditional sacrificial victims - show beyond doubt that ritual sacrifice was involved, and that the sacrifices in the rebellion were not just executions in revenge against the police.

Human sacrifice appears to have been well-established among the hill tribes of the eastern Ghats before the 19th century. The sacrificial ritual recorded by the first Europeans to hear of it was known as meriah, in which a deity was propitiated and strips of flesh were torn off the victim. The policy of the East India Company had been not to interfere with native rituals unless absolutely necessary. However, along with thuggee - ritualised strangling - meriah became the focus of evangelical zeal in the early Victorian period, and an ‘Agency for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice and Female Infanticide’ worked to end the practice in 1837-54. Despite the apparent success of their efforts, the evidence of the Rumpa rebellion suggests that meriah was not fully suppressed, and well into the 20th century anthropologists studying the hill tribes heard rumours of its continuation deep in the jungle.

Only one European eyewitness account of a meriah sacrifice is known to survive, in Major-General John Campbell’s A Personal Narrative of Thirteen Years Service amongst the Wild Tribes of Khondistan for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice, published in 1864. You can read the full text of the book here. Campbell’s assistant, Captain Frye,

was informed one day of a sacrifice on the very eve of consummation; the victim was a young and handsome girl, fifteen or sixteen years old. Without a moment’s hesitation, he hastened with a small body of armed men to the spot indicated, and on arrival found the Khonds already assembled with their sacrificing priest, and the intended victim prepared for the first act of the tragedy. He at once demanded her surrender; the Khonds, half-mad with excitement, hesitated for a moment, but observing his little party preparing for action, they yielded the girl. Seeing the wild and irritated state of the Khonds, Captain Frye very prudently judged that this was no fitting occasion to argue with them, so with his prize he retraced his step to his old encampment …

Campbell was told about another sacrifice by a native eyewitness:

Click on this jacket image to go to the book page and see all international editions with links to Amazon and other sellers.

… the intended victim was dragged to the place of sacrifice, and his head and neck introduced into the cleft of a strong bamboo split in two, the ends of which were secured and held by the sacrificers. The presiding priest then advanced, and with an axe broke the joints of the legs and arms, after which the rest stripped the flesh off the bones with their knives, and each man having secured a piece buried it in the fields.

The victims could be kidnapped strangers, a practice reported near Rumpa as late as the 1870s. The woodcut shown at the top of this posting from Campbell’s book - undoubtedly based on Captain Frye’s account - portrays meriah in all of its horror: the female victim tied to a post, stupefied by toddy; the frenzied crowd, themselves intoxicated and excited by drumming; and the priest and other men bearing vicious knives about to tear the girl to pieces, cutting off flesh to take away and bury in their own jungle clearings as an offering to boost the fertility of the land.

The quoted extract in bold is copyright David Gibbins, from The Tiger Warrior (London and New York, 2009).

The Rumpa Rebellion (India), 1879-80: Human sacrifice in the jungle

A woodcut from John Campbell’s A Personal Narrative of Thirteen Years Service amongst the Wild Tribes of Khondistan for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice, published in 1864.

This is the first of several planned postings related to the 1879-80 Rumpa Rebellion in India, a setting in my novel The Tiger Warrior that I researched extensively using primary sources in the India Office Collections of the British Library. The rebellion was a tribal uprising in the jungle of southern India, and was countered by a brigade-sized expedition of the Madras army including a company of sappers led by my ancestor Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers. Once these postings are complete a comprehensive account of the rebellion and the British military deployment with full references will be added as a PDF.

In my novel The Tiger Warrior, set partly in India during the Victorian period, Lieutenant John Howard of the Madras Sappers takes cover with his men on an armoured river steamer deep in the jungle of southern India, part of a force deployed against a tribal rebellion in the Rumpa district of the eastern Ghats in 1879. As bullets spatter off the metal plating, Howard watches a horrifying ritual unfold among the rebels gathered on the opposite river bank, one that leads him to pick up a rifle and take a course of action that he could never have thought imaginable:

Photo of me shooting a Snider-Enfield rifle of the type that Lieutenant Howard uses in my novel (photo: Alan Gibbins).

A boy, not much older than his own son, was chained to the pole. His head was lolling like the man’s, but his body shuddered, still alive. Four of the women held out his little arms and legs. The man in the tiger skin approached, and took up a smaller pole, like the handle of an axe. He tapped the boy on the head with it, and then tapped each of the boy’s limbs. Only they were not taps. Howard had been seeing everything in slow motion, and as his mind replayed it, he saw the little limbs each crack and flop away, broken like boughs of dry wood. The women let go, and the small body hung like a rag doll from the chain that held his neck. A rope tied to the top of the pole was pulled, and the cock began to whirl round and round, followed by the women, who circled it. Among the swirling robes there were flashes of blades held in readiness, glinting. The boy raised his head, and Howard was sure he heard crying, the helpless crying of a child that seemed to reach out to him, that seemed to come from a child of his own. It was unbearable.

The fictional Lieutenant Howard is closely based on an ancestor of mine who served in the rebellion – Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale of the Madras Sappers, pictured below – and the incident is inspired by actual accounts of ritualized killing carried out by the rebels. The 1908 Imperial Gazeteer of India reports ‘strong reasons for believing’ that two men were sacrificed at Dummagudem near Rumpa in 1876, and that men were ‘openly sacrificed’ during the Rumpa rebellion. First-hand accounts of ritualized killings are found in the reports of the Madras Judicial Proceedings in the India Office collection of the British Library. In March 1879, the rebel leader Tamman Dora took his police captives to a sacred place where he beheaded two of them with a sword in the presence of several hundred tribesmen. The killing was allegedly a ritual sacrifice in honour of Melveri, a goddess ‘very partial to human victims’. In September of that year, the sacrifice of a villager was recounted by a native eyewitness (reported in the Proceedings, 8 March 1880):

Lieutenant Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers, one of a small number of British officers involved in the 1879-80 Rumpa expedition who may have witnessed evidence of human sacrifice first-hand.

They sacrificed him to Gudapu Mavili. They made him sit down, then Chendrayya struck him with his sword. Zunapalu got up and began to run away; Chendrayya’s people threw stones at him; Zunapalu fell down and then Chendrayya’s men cut off his head.

The police later found the headless body. On 30 March 1880 the Proceedings reported an assault by troops on a village from which thirty rebels escaped, and where they found ‘three pariahs … who said they had been reserved for sacrifice’; they also found the headless body of the village ‘watcher’, ‘sacrificed.’ Another report notes that four pariahs were sacrificed by the rebels on 18 May. These accounts, identifying pariahs, ‘outcasts’ - traditional sacrificial victims - show beyond doubt that ritual sacrifice was involved, and that the sacrifices in the rebellion were not just executions in revenge against the police.

Human sacrifice appears to have been well-established among the hill tribes of the eastern Ghats before the 19th century. The sacrificial ritual recorded by the first Europeans to hear of it was known as meriah, in which a deity was propitiated and strips of flesh were torn off the victim. The policy of the East India Company had been not to interfere with native rituals unless absolutely necessary. However, along with thuggee - ritualised strangling - meriah became the focus of evangelical zeal in the early Victorian period, and an ‘Agency for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice and Female Infanticide’ worked to end the practice in 1837-54. Despite the apparent success of their efforts, the evidence of the Rumpa rebellion suggests that meriah was not fully suppressed, and well into the 20th century anthropologists studying the hill tribes heard rumours of its continuation deep in the jungle.

Only one European eyewitness account of a meriah sacrifice is known to survive, in Major-General John Campbell’s A Personal Narrative of Thirteen Years Service amongst the Wild Tribes of Khondistan for the Suppression of Human Sacrifice, published in 1864. You can read the full text of the book here. Campbell’s assistant, Captain Frye,

was informed one day of a sacrifice on the very eve of consummation; the victim was a young and handsome girl, fifteen or sixteen years old. Without a moment’s hesitation, he hastened with a small body of armed men to the spot indicated, and on arrival found the Khonds already assembled with their sacrificing priest, and the intended victim prepared for the first act of the tragedy. He at once demanded her surrender; the Khonds, half-mad with excitement, hesitated for a moment, but observing his little party preparing for action, they yielded the girl. Seeing the wild and irritated state of the Khonds, Captain Frye very prudently judged that this was no fitting occasion to argue with them, so with his prize he retraced his step to his old encampment …

Campbell was told about another sacrifice by a native eyewitness:

Click on this jacket image to go to the book page and see all international editions with links to Amazon and other sellers.

… the intended victim was dragged to the place of sacrifice, and his head and neck introduced into the cleft of a strong bamboo split in two, the ends of which were secured and held by the sacrificers. The presiding priest then advanced, and with an axe broke the joints of the legs and arms, after which the rest stripped the flesh off the bones with their knives, and each man having secured a piece buried it in the fields.

The victims could be kidnapped strangers, a practice reported near Rumpa as late as the 1870s. The woodcut shown at the top of this posting from Campbell’s book - undoubtedly based on Captain Frye’s account - portrays meriah in all of its horror: the female victim tied to a post, stupefied by toddy; the frenzied crowd, themselves intoxicated and excited by drumming; and the priest and other men bearing vicious knives about to tear the girl to pieces, cutting off flesh to take away and bury in their own jungle clearings as an offering to boost the fertility of the land.

The quoted extract in bold is copyright David Gibbins, from The Tiger Warrior (London and New York, 2009).

May 13, 2015

THE SWORD OF ATTILA: military map-makers, Roman and Victorian

One of the characters I most enjoyed creating in my novel Total War Rome: The Sword of Attila was Gnaeus Uago Alentius, a senior tribune of the fabri – the Roman equivalent of the Corps of Engineers – who oversees a military mapping unit in Rome. I'd imagined that by the 5th century AD, Roman proficiency in field survey and road-tracing might have led to a kind of topographical department in the army, with the fabri close to creating detailed maps akin to the early British Ordnance Survey series - something that would have been halted by the collapse of the Roman army in the west shortly afterwards, leaving us no evidence of their work. When my protagonists Flavius and Arturus first meet Uago in his map room, he tells them about his campaign experiences as a young officer:

A 13th century rendition of part of the Tabula Peutingeriana (click to enlarge), a Roman road itinerary probably set down in the 4th or 5th century AD - about the time of my novel. This section is particularly relevant to the story because in the land mass at the top it shows the river Danube, the route taken by my protagonists towards the Hun capital. Below that you can see the Adriatic Sea, the foot of Italy, Sicily and the North African coast. Clearly, rather than being an attempt at a geographically accurate map, this rendition is a framework for depicting the road networks and inter-relation between cities and towns - a little like the London underground map (this image is taken from an 1887 facsimile by Konrad Miller).

Uago stared into the middle distance, his brows furrowed. ‘It was during the Berber rebellion in the fifteenth year of Honorius’ reign, nearly forty years ago now. I’d been among the first batch of tribunes to graduate from the schola, set up only the year before in the wake of Alaric’s sack of Rome. My first job with the fabri had been to help clear the rubble created by the Goths on the Capitoline Hill, when they had tried to pull down the ruins of the old temple. After that I volunteered for frontier service, and was posted as second in command of a fabri numerus on the edge of the desert in Mauretania Tingitana. The limitanei garrison had been depleted to make up numbers in the Africa comitatenses, and when the rebellion started we were remustered as infantry milites. It was hard campaigning, with many men falling to disease and exhaustion, and there were no battles, only brief violent skirmishes and chasing shadows in the dark. Towards the end we reverted to our role as fabri and were used to make roads, improve fortifications and dig wells, much more to my liking than hunting down rebels and burning villages. I discovered a fascination for survey and mapmaking, and that’s been my calling ever since.’

‘Forty years is a long time to be in the army,’ Arturus said.

‘Aetius dug me out of retirement when he wanted a detailed new map to be made showing Attila’s conquests. He gave me free rein to call in the best cartographers from Alexandria and Babylon, and I’ve had the copyists in my scriptoria working day and night to get the map ready to despatch to the comitatenses and limitanei commanders.’

Part of my inspiration for Uago came not from ancient Rome, but from the military engineers the Victorian period – in particular, the many unsung officers of the British Royal Engineers who surveyed and mapped large parts of the world at the time, and built the roads, railways, canals, dams and public buildings that still provide the infrastructure for many of those countries today. Some of those officers had campaign experience - usually as young men commanding sapper companies in the field, if their early years after commissioning happened to coincide with a war or an expedition - but many had full and valuable careers without garnering any military glory. I was thinking in particular of my great-great grandfather, Colonel Walter Andrew Gale, Royal Engineers, who began in the late 1870s as a young sapper officer in an arduous jungle campaign in southern India – soon forgotten, like Uago’s Berber revolt – but then spent a long career in widely varying engineering roles, ranging from teaching survey at the School of Military Engineering at Chatham to civic engineering projects in India. Like Uago, who was brought out of retirement by the Roman general Aetius, Colonel Gale was 'dug up' - as he put it - by his friend Lord Kitchener at the outbreak of the First World War to work for Ordnance Survey, making maps for the front and not finally retiring until he had completed more than 40 years’ service, just as Uago had done.

Gale (gejl) Walter A., anglo, kolonelo. Nask. 9 nov. 1855, mortis 20. dec. 1924. En la brita armeo 1875-1911 (21 jarojn en Hindujo). E-istiĝis en 1907. Multa literatura laboro sub plumnomo Ŭoago. Citinda estas lia Konkordanco al Sentencoj de Salomono kaj manuskripta Konkordanco al Marta (ĉe BEA).

I had some fun with the name, too. ‘Uago’ is a perfectly plausible name of the Roman period, but it also happens to be the nom de plume used by Colonel Gale (made up from his initials, rendered as Uago or Uoago) when he wrote books and papers in Esperanto, the universal language that had a large following in the early years of the 20th century. You can see this in the entry on him in the Enciklopedio de Esperanto quoted opposite. Gale was a passionate Esperantist, an early Vice-President of the British Esperanto Assocation and a major benefactor. In the photo below you can see the star of the Esperanto movement carved into the foot of his tombstone in Kinnersley Churchyard, Herefordshire, not far from the site of a 1st century AD marching camp where I first studied the work of the Roman military fabri early in my own career as an archaeologist.

The quoted excerpt is from David Gibbins, 2015, Total War Rome: The Sword of Attila (London: Macmillan and New York: St Martin's Press) (for all editions and links, click here).

April 13, 2015

A Brown Bess musket of the War of 1812 period stamped MSR: De Meuron's Swiss Regiment?

Revised 16 September 2015

I purchased the musket in these photos several years ago in southern Ontario, Canada, from a dealer who had acquired it locally and believed that it had not previously been on the collector market. The musket is a flintlock 'India Pattern' of the Napoleonic Wars period, one of several million produced in England between 1793 and 1815. What particularly interested me were the unusual regimental markings on the barrel and the buttplate tang, and the possibility that this musket might have seen service in Canada during the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States.

The barrel-maker's name stamped beneath the barrel just forward of the breech.

The underside of the barrel is stamped with the name Russel, one of a family based in Wednesbury near Birmingham who supplied barrels to the Board of Ordnance from 1793 and to the East India Company from 1807. The swan-shaped neck dates the manufacture of the cock to before 1809, when a more robust ring-neck cock was introduced. Ordnance muskets could have been set up from stockpiled components manufactured some years previously, but in this case the introduction of an improved cock suggests that the older cock design would not have been used for Ordnance muskets after that date; 1809 therefore provides a likely terminus ante quem for the setting-up of the lock and the gun.

The two photos below (click to enlarge) clearly show the markings MSR. D. No. 9 stamped on the barrel in front of the breech and D No. 9 on the buttplate tang. Barrel stamps in this fashion are unusual among India Pattern muskets, though it is clear that the letters MSR must signify a regiment, the single letter D a company within the regiment and the number 9 a rack or issue number within the company.

This and the two photos below (click to enlarge) show a very similar India Pattern musket to mine also stamped MSR, and also from Ontario (photos: Dr Derek Booth).

I know of two parallels for the markings on my musket. The first is a musket sold recently by a dealer in the US with a Pattern 1809 cock and the barrel stamp M.S.R. F. No. 87., differing from mine only in the dies used for the stamps and in the first three letters being separated by full-stops. The musket was apparently also stamped on the buttplate tang and on the ramrod (the ramrod was missing from my musket). According to the dealer, the musket came originally from Canada. Another musket from Canada, said to have come from a farm in the Niagara region of southern Ontario, is illustrated opposite and below. Excitingly, the stamp gives a rack number only two away from mine, in the same company - MSR.D No.7. The dies used look identical, and the lock also has a swan-neck cock. The wear on the buttplate tang - leaving only the D visible - suggests a similar history of use as the overall wear on my musket, indicative of regimental service as well as the kind of later use imaginable for these muskets as militia and farm guns.

Which regiment is signified by MSR? Having considered a wide range of possibilities for the period, including British, colonial British and US militia regiments, I've concluded that the most likely candidate is De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment, one of two Swiss regiments in the British army to serve in Canada during the War of 1812. The regiment is commonly referred to as ‘Régiment de Meuron’, but during its years in British service it was often styled in anglicised form - for example, a discharge certificate from 1816 that you can see here refers to ‘His Majesty’s De Meuron Regiment of Foot.’ An officers’ dress specification for its time in British service quoted in the main modern history of the regiment, by Guy de Meuron, a descendant of the founder, notes that the belt and helmet plates were inscribed ‘De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment', and exactly that wording appears on a military button of the regiment recently found by a metal-detectorist in England. All of this suggests that MSR would have been an obvious abbreviation to stamp on muskets when the decision was made to mark them in this way.

A button from England with 'De Meuron's Swiss Regiment' around the edge. For details of the find click here.

In a record of new arms received by British regiments serving in North America during the War of 1812 – listing the most recent complete rearming noted in the sources, or the most recent significant issue – De Witt Bailey notes that De Meuron’s Regiment received 400 muskets and bayonets in May 1807, a date that might fit well with my musket. What makes an association with De Meuron’s Regiment even more compelling is the likelihood that the regiment’s muskets remained in Canada after the war. British regiments returning from colonial service commonly left their small arms in local Ordnance stores, something that would have made particular sense for a regiment that was not only leaving but also disbanding. Before De Meuron’s Regiment left Lower Canada in 1816, some 343 officers and men accepted an offer to settle locally – many in the Perth area of eastern Ontario -with substantial land grants and a gratuity. They were encouraged to join the militia, and it seems likely that such men would have been allowed to keep their muskets. Some 88 veterans of the regiment, uniformed and provided with muskets, formed part of Lord Selkirk’s 1816 expedition to the Red River Colony in present-day Manitoba, seeing action in the ‘Pemmican War’ between the Hudson’s Bay and North-West Companies and in some cases settling there permanently after the conflict was over.

This attribution must remain tentative until more evidence comes to light. However, the second of the parallels noted here, MSR.D No.7, was brought to my attention by a collector who had seen the first version of this article, and that gives me hope that others may exist out there to strengthen the case still further - so I'd be very interested to hear from anyone who might have another of these muskets, or knows of further evidence that MSR may have been an abbreviation used by De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment during their period in British service.

For their ideas and help with this research I'm very grateful to David Harding, John Denner, Stuart Mowbray, Dr Derek Booth (who supplied the photos of the second musket illustrated here) and members of the British Militaria Forum who have responded to my posts on this subject over the last few years.

For images and video of a Sea Service pistol of similar date, click here.

'Colonists on the Red River in North America', c. 1822, by Peter Rindisbacher, a young Swiss artist who was one of the original settlers under Lord Selkirk. The man with the military greatcoat and cap in the middle is thought to be a De Meuron Regiment veteran; the upper of the two long guns on the wall has the instantly recognisable butt shape of a Brown Bess musket. National Archives of Canada.

References

Bailey, De Witt. Small Arms of the British Forces in America 1664-1815. Mowbray Publishing, Woonsocket, 2009, p. 286.

Bailey, De Witt, and Nie, D.A., 1978, English Gunmakers. Arms and Armour Press (on the Russell family).

Goldstein, E and Mowbray, S. The Brown Bess. Mowbray Publishing, Woonsocket, 2010, p. 142-159.

Harding, David, Smallarms of the East India Company. Vol. 1, Procurement and Design. Foresight Books, London, 1997, Appendix C (Suppliers of Musket Parts), p. 316.

Lawson, C.C.P. and Severin, J.P. De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment, 1814-1816. Military Collector and Historian, Vol 9, issue 1 (1957), p. 77.

Meuron, Guy de. Le Régiment Meuron, 1781-1816. Le Forum Historique, Lausanne, 1982.

A Brown Bess musket of the Napoleonic Wars stamped MSR: De Meuron's Swiss Regiment?

I came across the musket in these photos several years ago in Ontario, Canada, and since then have searched extensively for parallels for the unusual regimental markings on the barrel and buttplate tang. The musket is a flintlock 'India Pattern' of the Napoleonic Wars period, one of several million produced between 1793 and 1815 that saw service in British and colonial regiments around the world, including the War of 1812-14 between Britain and the United States.

The barrel-maker's name stamped beneath the barrel just forward of the breech.

The swan-neck cock dates the manufacture of the lock – or that component of it – to before 1809, when a more robust ring-neck cock was introduced. The underside of the barrel is stamped with the name Russel, one of a family based in Wednesbury near Birmingham who supplied barrels to the Board of Ordnance from 1793 and to the East India Company from 1807. What particularly interested me were the markings MSR. D. No. 9 stamped on the barrel in front of the breech and D No. 9 on the buttplate tang, as seen in the two images below (click to enlarge). The letters MSR would normally signify a regiment, and the letter D a company. I have seen only one parallel for this marking, on a musket sold by a dealer in the US with a Pattern 1809 cock and the barrel stamp M.S.R. F. No. 87., differing from mine only in the dies used and in the first three letters being separated by periods. The musket was apparently also stamped on the buttplate tang and on the ramrod (the ramrod was missing from my musket).

Having considered a wide range of possibilities for the period, including British, colonial British and US militia regiments, I've concluded that the most likely candidate for these markings is De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment, one of two Swiss regiments in the British army to serve in Canada during the War of 1812. The regiment is commonly referred to as ‘Régiment de Meuron’, but during its years in British service it was often styled in anglicised form - for example, a discharge certificate from 1816 that you can see here refers to ‘His Majesty’s De Meuron Regiment of Foot.’ An officers’ dress specification for its time in British service quoted in the most extensive modern history of the regiment, by Guy de Meuron, a descendant of the founder, notes that the belt and helmet plates were inscribed ‘De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment.', and exactly that wording appears a military button of the regiment recently found by a metal-detectorist in England. All of this suggests that MSR would have been an obvious abbreviation to stamp on muskets and other equipment and stores.

A button from England with 'De Meuron's Swiss Regiment' around the edge. For details of the find click here.

In a list of new arms received by British regiments serving in North America during the War of 1812 – the most recent complete rearming or the most recent significant issue – De Witt Bailey notes that De Meuron’s Regiment received 400 muskets and bayonets in May 1807, a date that might fit well with my musket. What makes an association with De Meuron’s Regiment even more compelling is the likelihood that the regiment’s muskets remained in Canada after the war. British regiments returning from colonial service commonly left their small arms in local Ordnance stores, something that would have made particular sense for a regiment that was disbanding. Before De Meuron’s Regiment left Lower Canada in 1816, some 343 officers and men accepted an offer to settle locally – many in the Perth area of eastern Ontario -with substantial land grants and a gratuity. They were encouraged to join the militia, and it seems reasonable to think that such men would have been allowed to keep their muskets. Some 88 veterans of the regiment, uniformed and provided with muskets, formed part of Lord Selkirk’s 1816 expedition to the Red River Colony in present-day Manitoba, seeing action in the ‘Pemmican War’ between the Hudson’s Bay and North-West Companies and a number of them settling there as well.

This attribution must of course remain guesswork until more evidence comes to light. I'd be very interested to hear from anyone who might have another of these muskets, or knows of further evidence that MSR may have been an abbreviation used by De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment during their period in British service.

For images and video of a Sea Service pistol of similar date, click here.

'Colonists on the Red River in North America', c. 1822, by Peter Rindisbacher, a young Swiss artist who was one of the original settlers under Lord Selkirk. The man with the military greatcoat and cap in the middle is thought to be a De Meuron Regiment veteran; the upper of the two long guns on the wall has the instantly recognisable butt shape of a Brown Bess musket. National Archives of Canada.

References

Bailey, De Witt. Small Arms of the British Forces in America 1664-1815. Mowbray Publishing, Woonsocket, 2009, p. 286.

Bailey, De Witt, and Nie, D.A., 1978, English Gunmakers. Arms and Armour Press (on the Russell family).

Goldstein, E and Mowbray, S. The Brown Bess. Mowbray Publishing, Woonsocket, 2010, p. 142-159.

Harding, David, Smallarms of the East India Company. Vol. 1, Procurement and Design. Foresight Books, London, 1997, Appendix C (Suppliers of Musket Parts), p. 316.

Lawson, C.C.P. and Severin, J.P. De Meuron’s Swiss Regiment, 1814-1816. Military Collector and Historian, Vol 9, issue 1 (1957), p. 77.

Meuron, Guy de. Le Régiment Meuron, 1781-1816. Le Forum Historique, Lausanne, 1982.

April 5, 2015

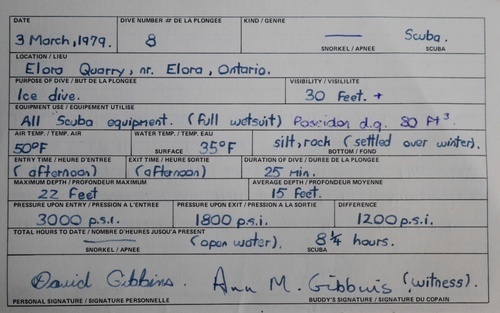

My first ice dive, Elora Quarry, Ontario, 1979

A page from my log for that dive.

These pictures were taken during my first ice dive, at Elora Quarry, near Guelph, Ontario, Canada, on 3 March 1979, when I was 16. They're a little grainy because I've had to digitally remaster them from small prints taken with a pocket camera. I'd qualified as a diver the year before, and this was my eighth open-water dive. The quarry was a favourite local dive spot for my club, the Guelph and District Underwater Association (GADUA), and they organised at least one ice dive each winter. The pictures show me with my youngest brother Hugh, and also show my instructor, Tom D'Entremont (in the blue coat and sunglasses). The final picture in the gallery is of my dive buddy, Steve Aitken, taken a year later on another dive at the same spot.

This first ice dive was an exhilarating experience for me. I was only wearing a wetsuit, but I can remember being very warm before the dive because of having kitted up well in advance and waiting in the sun for my turn. I was using equipment typical of the day, including a bouyancy compensator that was little more than a life jackets (buoyancy compensation being via the mouthpiece hose, and the only other source of inflation being an emergency CO2 cartridge), and no octopus rig. Nevertheless, the dives were very safely managed, as these pictures show, with a secure roping system and a safety diver always ready at the hole. My diving course had extended over nearly a year before this, allowing the time needed to learn all aspects of diving theory and develop advanced skills, and I had an excellent instructor as well as a dive buddy I'd trained with from the outset and trusted completely. I owe a lot to Tom and Steve! And I still use the Poseidon regulator that you can see in these pictures, one of my most prized possessions.

Click on the images to enlarge.

April 2, 2015

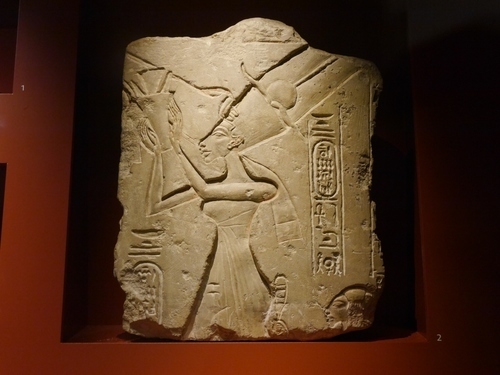

PYRAMID: Akhenaten in the Ashmolean

You don’t have to go to Egypt to see spectacular artefacts from the 14th century BC reign of the pharaoh Akhenaten – if you’re in England you can go to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and see a beautiful display of material from Akhenaten’s capital at Tell el-Amarna, excavated by the British archaeologist Flinders Petrie and his successors from the late 19th century. The display is small and intimate and yet contains some of the most famous Akhenaten artefacts, including the fresco of the two princesses shown below and the relief carving of Nefertiti being touched by the Aten. While I was writing my novels Pharaoh and Pyramid I visited the exhibit several times to get that sense of immediacy with the past that’s so important to me, from seeing – and touching – artefacts from the period I’m writing about, and to ponder what it was that made the ‘Amarna’ period in Egypt so distinctive and appealing.

By ditching the old religion to focus on worship of the sun-god, the Aten, Akhenaten also dispensed with the complex iconography which can bedevil the appreciation of Egyptian art, and probably inhibited its development. Instead of having to remember the names of gods and symbols you can bask in the sensuality and humanity of the depictions of Akhenaten’s family, and the exuberance and impressionism of the marshland scenes of birds and plants. Although this too has a religious aspect – Akhenaten and his family were the sole mediators with the Aten, and the natural world provided the offerings that were made to the god – one of the fascinating aspects for me is the similarity of the paintings in particular with Aegean art of this period, produced in Greece and Crete. While this may represent a kind of artistic flowering across the East Mediterranean at this time, when increased trade and the movement of people and ideas could have spread a common artistic taste, it may also reflect political and dynastic ties – something I touch on in my novel Pyramid. At the Ashmolean you can judge this for yourself because one of the other great collections of the museum is the Aegean Bronze Age material brought back by Arthur Evans from his excavations at Knossos on Crete, now also superbly displayed following the refurbishment of the museum and its reopening in 2009.

The galleries below contains some photos from the Amarna exhibit I took during a recent visit. Click on the images to enlarge them. The first gallery shows some of the beautiful cobalt-blue pottery of the period, decorated with palm designs reminiscent of the wall paintings of Amarna and probably representing the flowered garlands that were draped around these vessels, most of them probably for wine. Although the cobalt colouring is not directly paralleled in Aegean art of this period the style and touch is reminiscent of Minoan and Mycenaean pottery painting. The fourth photo emphasizes this connection, showing two Egyptian ‘pilgrim flasks’ copying Aegean forms of this period. I’ve handled similar flasks from a shipwreck at Uluburn off Turkey which contained material from many different cultures that participated in the trade and diplomatic networks of this period, including a gold ring with the cartouche of Nefertiti.

The paintings below are from a plaster pavement showing wild geese taking flight from a marsh, a wall-painting depicting a shrike on a papyrus stem, and the so-called ‘Princesses Fresco’, a fragment of wall-painting showing two daughters of Akhenaten and Nefertiti seated with their parents, their images now lost. The fourth photo shows fragments of faience and glass ornaments, products of a thriving industry at el-Amarna used to decorate royal dwellings and private houses.

The final four images show a limestone window grille from a house at el-Amarna, a lintel from a doorway with the cartouches of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and those of the Aten, with traces of blue paint visible (as well as paint on the cornice above), and two small relief sculptures of Nefertiti, the first one a famous image showing an arm of the Aten extending to touch her – an image of intimacy in keeping with much else in Amarna art – and the second one clearly showing the sun-disk rays of the Aten.

With the reinstatement of the old religion after Akhenaten’s death the cartouches and images of the pharaoh were largely destroyed, meaning that most finds are damaged or defaced and have come from rubbish deposits at Amarna. The one image of the pharaoh in the Ashmolean exhibit is the headless sandstone sculpture beside Nefertiti in the centre of the room, showing the distinctive bodily shape characteristic of images of Akhenaten – whether the result of an actual physical condition or a representation of the androgynous nature of the Aten is impossible to tell. Akhenaten’s true appearance thus remains an enigma, but something more important about him is revealed in the other artefacts in the room – evidence of a cultural flowering in which Egyptian artists were briefly released from the shackles of the old religion, and showed that they were as capable of expression as free and pleasing as the art of the Aegean world at this period.