Steve Hely's Blog, page 14

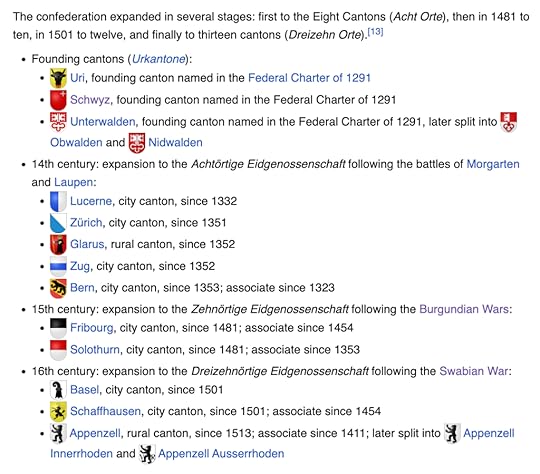

June 29, 2024

Stompin’ at the Savoy

When you are in Annecy, France you are in the department of Haute-Savoie, just above the department of Savoie. The counts of Savoy and the House of Savoy were a whole scene, and the Savoy is “a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps,” as Wiki tells us.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south and west and to the Aosta Valley in the east.

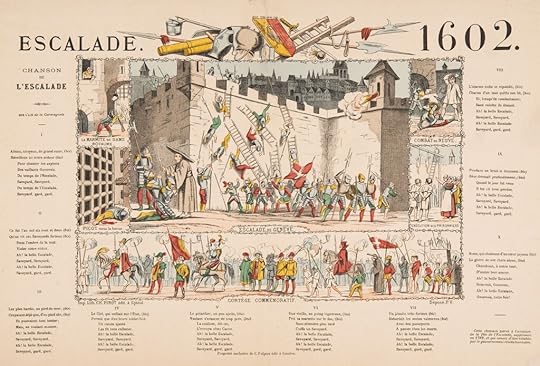

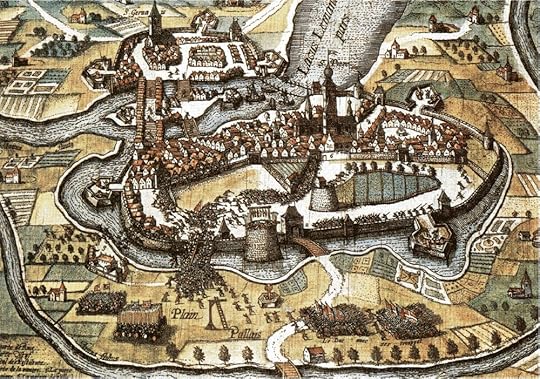

The Savoy does not include the city of Geneva itself. During an event known as the Escalade, in December 1602, the Savoyards attacked Geneva, but were repelled.

Druckgraphik. Am Rand der Text des Chanson

Druckgraphik. Am Rand der Text des Chanson(Supposedly) the late night cooks caught the sneaking Savoyards and dumped boiling pots of stew on them and alerted everybody.

Although the armed conflict actually took place after midnight, in the early morning on 12 December, celebrations and other commemorative activities are usually held on 11 December or the closest weekend. Celebrations include a large marmite (cauldron) made of chocolate and filled with marzipan vegetables and candies wrapped in the Geneva colours of red and gold… Teenagers tend to throw eggs, shaving cream, and flour at each other as part of the celebration. The high school students parade together by first going to “conquer” each other and end up in the central square of the old town after walking through the rues basses to the plaine de Plainpalais and back.

On the sleepless cook does history turn, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. So ended Savoyard expansion and stayed Geneva-ese indepenence.

The first count of Savoy was Humbert I:

Humbert is the progenitor of the dynasty known as the House of Savoy. The origins of this dynasty are unknown, but Humbert’s ancestors are variously said to have come from Saxony, Burgundy or Provence.

That’s as far back as we can get on Savoy. As Bob Dylan :

But that pedigree stuff, that only works so far. You can go back to the ten-hundreds, and people only had one name. Nobody’s gonna tell you they’re going to go back further than when people had one name.

In 1860 the Duchy of Savoy became part of France in a deal where France agreed to support unifying Italy. By then the House of Savoy was the royal family of Italy, and they kept on until 1946. Since then they’ve fallen rather hard, I recommend this wikpedia section, The House of Savoy Today. Vanity Fair article type stuff. Maybe Princess Vittoria is the current heiress, I dunno, it gets mixed up with the cousins. Suffice to say that the House of Savoy is at a low ebb in their thousand year journey.

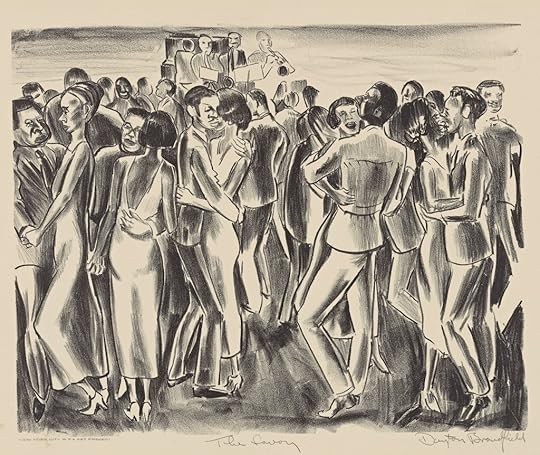

The word Savoy associates in my mind to “Stompin at the Savoy” and The Savoy Hotel. How did this word spread?

Stompin’ at the Savoy took its name from the Savoy Ballroom, which was once at 596 Lenox Avenue in Harlem.

(those images from the Savoy Ballroom wiki)

That Savoy took its name from the famed London hotel:

Built by the impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte with profits from his Gilbert and Sullivan opera productions, it opened on 6 August 1889. It was the first in the Savoy group of hotels and restaurants owned by Carte’s family[a] for over a century. The Savoy was the first hotel in Britain to introduce electric lights throughout the building, electric lifts, bathrooms in most of the lavishly furnished rooms, constant hot and cold running water and many other innovations. Carte hired César Ritz as manager and Auguste Escoffier as chef de cuisine; they established an unprecedented standard of quality in hotel service, entertainment and elegant dining, attracting royalty and other rich and powerful guests and diners.

(Then Ritz and Escoffier left in a scandal, they were stealing booze and semi-embezzling. Ritz of course would go on to have his own chain, that also generated music:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aNFffHQOXMc

)

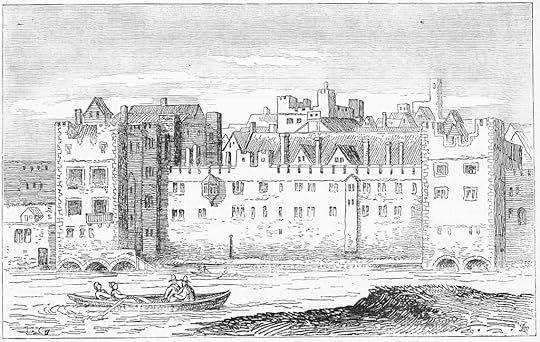

The London hotel was called Savoy because it was on the location of the Savoy Palace. Eleanor of Provence married King Henry III in 1236. He was 28, she was maybe.

Wiki tells us:

she was very much hated by the Londoners. This was because she had brought many relatives with her to England in her retinue; these were known as “the Savoyards”, and they were given influential positions in the government and realm. On one occasion, Eleanor’s barge was attacked by angry Londoners who pelted her with stones, mud, pieces of paving, rotten eggs and vegetables.

One of these Savoyards was her uncle Peter, who was granted some land where he built Savoy Palace:

The Savoy was the most magnificent nobleman’s house in England. It was famous for its owner’s magnificent collection of tapestries, jewels, and other ornaments. Geoffrey Chaucer began writing The Canterbury Tales while working at the Savoy Palace as a clerk.

It was destroyed in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1351. Later on the site was built Savoy Hospital:

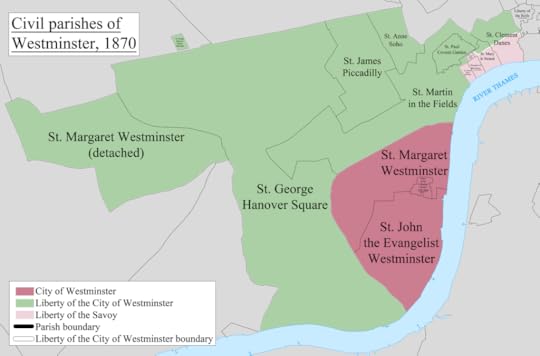

Later this area became a little precinct:

There was a chapel there, Savoy Chapel:

In 1912 it was the scene of a suffragette wedding between Victor and Una Duval. The wedding was attended by leading suffragettes and the wedding caused much debate because the bride refused to say “and obey”, despite the intervention of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

And nearby D’oyly Carte built the Savoy Theatre and the Savoy Hotel.

And there we have some history of “Savoy” as a concept. Once again a cultural and historical puzzle that’s come up in our travels has been followed towards the source, with illuminating new stories and details that have enriched our experience of life. We’ve shared it with you, the reader, and hope you’ve found it edifying.

Let’s all listen to Stompin’ At The Savoy, we’ll go with the version by… Art Tatum:

June 27, 2024

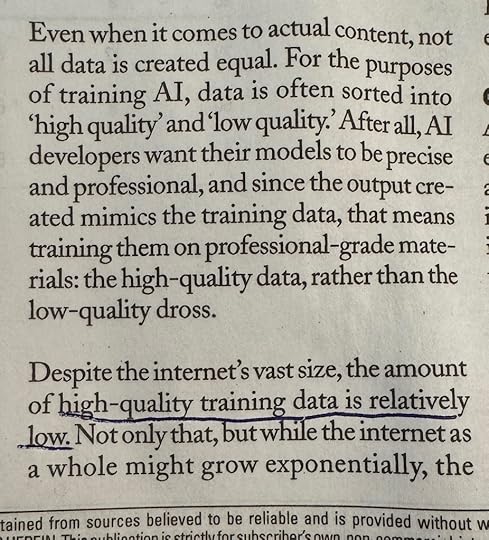

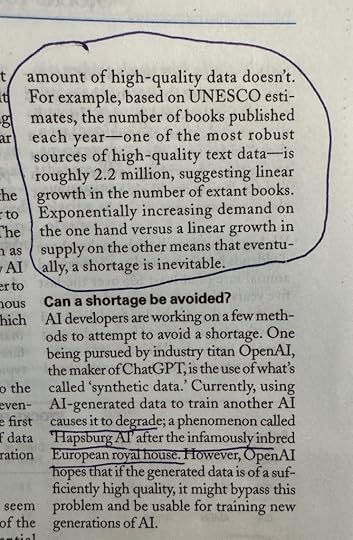

Quality data and Hapsburg AI

That’s from the June 7 issue of ValueLine. I subscribed after I saw this clip:

Not even sure what year that’s from.

Quality has been on my mind.

Quality … you know what it is, yet you don’t know what it is. But that’s self-contradictory. But some things are better than others, that is, they have more quality. But when you try to say what the quality is, apart from the things that have it, it all goes poof! There’s nothing to talk about. But if you can’t say what Quality is, how do you know what it is, or how do you know that it even exists? If no one knows what it is, then for all practical purposes it doesn’t exist at all. But for all practical purposes it really does exist. What else are the grades based on? Why else would people pay fortunes for some things and throw others in the trash pile? Obviously some things are better than others … but what’s the betterness? … So round and round you go, spinning mental wheels and nowhere finding anyplace to get traction. What the hell is Quality? What is it?

As the guy says in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. At the Smithsonian you can see Pirsig’s motorcycle:

I was at See’s Candy the other day:

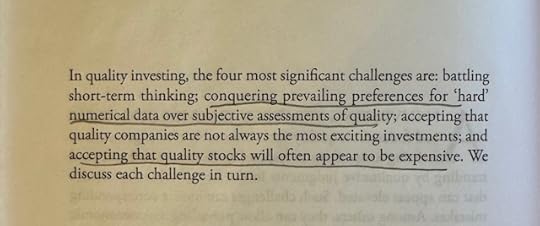

Recently I read this book:

There are some interesting case studies (although they skew a bit Euro):

Will AI ever produce something of “quality”? I have yet to see it.

June 26, 2024

June 25-26

Lt. James Bradley led a detachment of Crow Indian scouts up the Bighorn Valley during the summer of 1876. In his journal he records that early Monday morning, June 26, they saw the tracks of four ponies. Assuming the riders must be Sioux, they followed these tracks to the river and came upon one of the ponies, along with some equipment which evidently had been thrown away. An examination of the equipment disclosed, much to his surprise, that it belonged to some Crows from his own command who had been assigned to General Custer’s regiment a few days earlier.

While puzzling over this circumstance, Bradley discovered three men on the opposite side of the river. They were about two miles away and appeared to be watching. He instructed his scouts to signal with blankets that he was friendly, which they did, but for a long time there was no response. Then the distant men built a fire, messages were exchanged by smoke signal, and they were persuaded to come closer.

They were indeed Crow scouts: Hairy Moccasin, Goes Ahead, White Man Runs Him. They would not cross the river, but they were willing to talk.

Bradley did not want to believe the story they told, yet he had a feeling it was true. In his journal he states that he could only hope they were exaggerating, “that in the terror of the three fugitives from the fatal field their account of the disaster was somewhat overdrawn.”

The news deeply affected his own scouts. One by one they went aside and sat down, rocking to and fro, weeping and chanting. Apart from relatives and friends of the slain soldiers, he later wrote, “there were none in this whole horrified nation of forty millions of people to whom the tidings brought greater grief.”

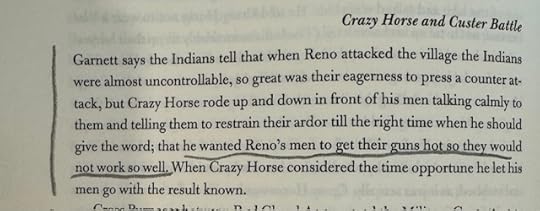

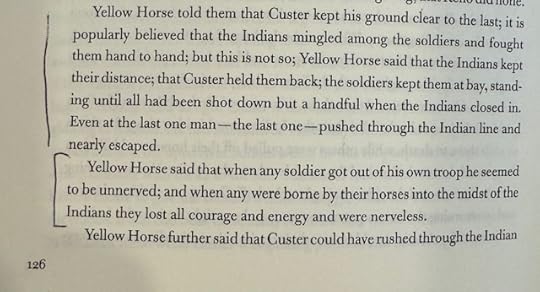

There were no literate survivors to the “last stand” event of June 25, 1876, so we have no firsthand written accounts. What happened was pieced together first from a sort of crime scene investigation. Later, interviews with participants were done, but cultural and linguistic gaps remained. Thomas Marquis, who lived among the Northern Cheyenne and knew many of them, wrote a book whose conclusions were so shocking it couldn’t be published in his lifetime.

Later, art, illustrations, apparently by eyewitnesses emerged, much of it quite vivid.

How about this:

or this:

Those found in:

What was this war about, anyway?:

June 9, 2024

Geneva Conventions (Swiss History Part Seven)

I believe this will conclude our unit on the history of Switzerland. Here you can find Part One about pre-Switzerland to the Dark Ages, Part Two about the Bernese chronicles, Part Three about founding myths like William Tell and the Rütli oath, Part Four about the various leagues up to the Congress of Vienna, Part Five about Steinberg’s Why Switzerland, and Part Six about Calvin/Cauvin’s Geneva.

Henry Dunant was a thirty one year old Swiss businessman who was trying to arrange some deals in French-held Algeria. He was running into problems, the land and water rights were all a jumble. So he came up with a plan:

Dunant wrote a flattering book full of praise for Napoleon III with the intention to present it to the emperor, and then traveled to Solferino to meet with him personally.

Napoleon III, Emperor of France, was in a war with Austria at the time. Dunant arrived on the evening after a massive battle. There were something like 40,000 dead and wounded people around.

No one was helping them.

Shocked, Dunant himself took the initiative to organize the civilian population, especially the women and girls, to provide assistance to the injured and sick soldiers. They lacked sufficient materials and supplies, and Dunant himself organized the purchase of needed materials and helped erect makeshift hospitals. He convinced the population to service the wounded without regard to their side in the conflict as per the slogan “Tutti fratelli” (All are brothers) coined by the women of nearby city Castiglione delle Stiviere. He also succeeded in gaining the release of Austrian doctors captured by the French and British.

When he got home, he wrote up a book called A Memory of Soferino, in which he described what he saw and set forth the idea that a neutral organization that could help the wounded in war would be valuable.

On February 7, 1863, the Société genevoise d’utilité publique [Geneva Society for Public Welfare] appointed a committee of five, including Dunant, to examine the possibility of putting this plan into action. With its call for an international conference, this committee, in effect, founded the Red Cross.

That’s from the Nobel Prize website; Dunant won the first ever Nobel Peace Prize.

A year after the founding of the Red Cross, the government of Switzerland invited all European countries as well as the US, Mexico and Brazil to a conference where they agreed on the first Geneva Convention “for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field”. They met in the Alabama room of Geneva’s city hall. Now, why was it called the Alabama room? Because that’s where an international tribunal met to work out the Alabama Claims, an international dispute between the US and the UK regarding grievances over Confederate raiders, including the Alabama, which were built in the UK and used against the US.

The Alabama.

So, Geneva already had a rep as a place for international meetings.

As for Dunant, he went bust. Says Nobel Prize.org:

After the disaster, which involved many of his Geneva friends, Dunant was no longer welcome in Genevan society. Within a few years he was literally living at the level of the beggar. There were times, he says, when he dined on a crust of bread, blackened his coat with ink, whitened his collar with chalk, slept out of doors.

For the next twenty years, from 1875 to 1895, Dunant disappeared into solitude. After brief stays in various places, he settled down in Heiden, a small Swiss village. Here a village teacher named Wilhelm Sonderegger found him in 1890 and informed the world that Dunant was alive, but the world took little note. Because he was ill, Dunant was moved in 1892 to the hospice at Heiden. And here, in Room 12, he spent the remaining eighteen years of his life. Not, however, as an unknown. After 1895 when he was once more rediscovered, the world heaped prizes and awards upon him.

Despite the prizes and the honors, Dunant did not move from Room 12. Upon his death, there was no funeral ceremony, no mourners, no cortege. In accordance with his wishes he was carried to his grave «like a dog»3.

The Red Cross calls me just about every day about giving blood. I’ve got to do that again.

June 7, 2024

Calvin’s Geneva (Swiss History Part Five or Six)

Previous posts on Swiss history.

Jean Cauvin was a twenty-four year old lawyer and scholar when his friend/ally gave a speech at the University of Paris that was so scandalous the guy had to leave town and move to Basel. The topic of the speech? Reforming the Catholic Church.

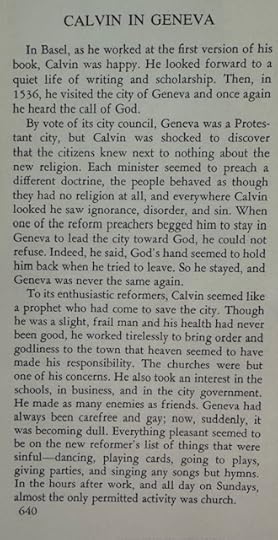

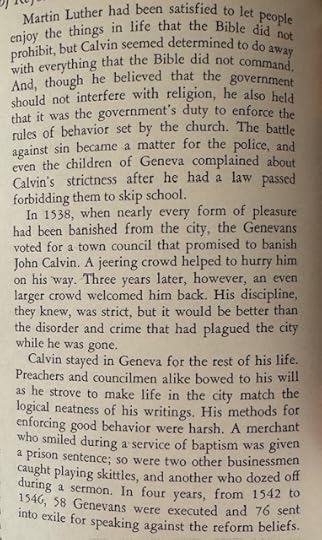

Shortly after events got so heated (y’all remember The Affair of the Placards) that Calvin had to leave town too. The Universal History of the World picks up:

The Universal History of the World, which I bought volume by volume for 50 cents each at the Needham Public Library, really fired up my youthful imagination. The book has a slight Protestant slant.

Wikipedia gives us Voltaire’s take on the reign of Calvin:

Voltaire wrote about Calvin, Luther and Zwingli, “If they condemned celibacy in the priests, and opened the gates of the convents, it was only to turn all society into a convent. Shows and entertainments were expressly forbidden by their religion; and for more than two hundred years there was not a single musical instrument allowed in the city of Geneva. They condemned auricular confession, but they enjoined a public one; and in Switzerland, Scotland, and Geneva it was performed the same as penance.”

Marilynne Robinson, in her Death of Adam, has a long essay sticking up for Calvin (she uses the spelling Cauvin):

Still, I would like to consider a little longer the strange figure of Jean Cauvin himself, because he is a true historical singularity. The theologian Karl Barth called him “a cataract, a primeval forest, something demonic, directly descending from the Himalayas, absolutely Chinese, marvelous, mythological.”

…

His commentaries on the Psalms and on Jeremiah are each about twenty-five hundred pages long in English translation, and he wrote commentary on almost the whole Bible, besides personal, pastoral, polemical, and diplomatic letters, treatises on points of doctrine, a catechism, and continuous revisions of his Institutes of the Christian Religion, the first, greatest, and most influential work of systematic theology the Reformation produced.

Robinson points out that by way of Geneva, many Protestant exiles who ended up in the future USA had an example of a republican type of government:

There are things for which we in this culture clearly are indebted to him, including relatively popular government, the relatively high status of women, the separation of church and state, what remains of universal schooling, and, while it lasted, liberal higher education, education in “the humanities.” All this, for our purposes, emanated from Geneva—in imperfect form, of course, but tending then toward improvement as it is now tending toward decline.

and:

In 1528 Geneva became an autonomous city governed by elected councils as the result of an insurrection against the ruling house of Savoy. Though the causes of the rebellion seem to have had little to do with the religious controversies of the period, in the course of it two preachers, Guillaume Farel and Pierre Viret, persuaded the city to align itself with the Reformation, then recruited Cauvin to guide the experiment of establishing a new religious culture in the newly emancipated city. That is to say, Calvinism developed with and within a civil regime of elections and town meetings…

Again, the republican institutions of Geneva were in place before Calvin set foot in that city; the Northern Netherlands freed itself and governed itself under Calvinist influence, which was strong but never exclusive; the New Englanders embraced a revolutionary order whose greatest exponents were Southerners.

She suggests we ease up on Calvin, after all he only executed the one heretic:

Bear in mind that Calvin approved the execution of only one man for heresy, the Spanish physician known as Michael Servetus, who had written books in which, among other things, he attacked the doctrine of the Trinity. One man is one too many, of course, but by the standards of the time, and considering Calvin’s embattled situation, the fact that he has only Servetus to answer for is evidence of astonishing restraint.

But she notes some difficult aspects:

Cauvin has an unsettling habit of referring to himself or to any human being as a “worm.”

I hope to learn more about John Calvin/Cauvin in Geneva. I find myself more drawn to Servetus:

Servetus also contributed enormously to medicine with other published works specifically related to the field, such as his Complete Explanation of Syrups

When Calvin died, they were worried his resting place would become a place of veneration, as for a saint, which he wouldn’t approve of, so he was buried in an unmarked grave.

June 5, 2024

History: rhyming or nah?

This is from the annual letter of Kanbrick, an investment company run by Warren Buffett protege Tracy Britt Cool:

You’ve maybe heard this Mark Twain quote before. Here’s what bothers me: Twain never said this. It’s not anywhere in his writings (easily searchable). Maybe he said it to some person who wrote it down? Well, Quote Investigator can’t find that quote anywhere in print until 1970.

Twain did write this:

NOTE. November, 1903. When I became convinced that the “Jumping Frog” was a Greek story two or three thousand years old, I was sincerely happy, for apparently here was a most striking and satisfactory justification of a favorite theory of mine—to wit, that no occurrence is sole and solitary, but is merely a repetition of a thing which has happened before, and perhaps often.

but that’s not quite the same thing, is it?

Now, you might say, who cares? But, like, Kanbrick’s job is researching, and curiosity, and getting facts right. If Twain made this interesting statement, wouldn’t it be worth finding out to whom he said it? or where he wrote it? and in what context? Even Mark Twain didn’t go around saying aphorisms. He said stuff in a setting. If Kanbrick had gone looking for the context, they wouldn’t have found it. So, they weren’t curious?

Look, let’s let Kanbrick off the hook here, they’re an investment firm. But here’s Ken Burns in a graduation speech at Brandeis University:

We continually superimpose that complex and contradictory human nature over the seemingly random chaos of events, all of our inherent strengths and weaknesses, our greed and generosity, our puritanism and our prurience, our virtue, and our venality parade before our eyes, generation after generation after generation. This often gives us the impression that history repeats itself. It does not. “No event has ever happened twice, it just rhymes,” Mark Twain is supposed to have said. I have spent all of my professional life on the lookout for those rhymes, drawn inexorably to that power of history. I am interested in listening to the many varied voices of a true, honest, complicated past that is unafraid of controversy and tragedy, but equally drawn to those stories and moments that suggest an abiding faith in the human spirit, and particularly the unique role this remarkable and sometimes also dysfunctional republic seems to play in the positive progress of mankind.

Now, Ken Burns at least gives the qualifier “supposed to have said,” but… Ken Burns made a 212 minute long documentary about Mark Twain! He must’ve steeped himself in Mark Twain! Did he not want to check out the context? I would guess that he just found it too good a quote to lose, and Mark Twain too good a source to put it too.

Here’s the IMF slapping down the quote without even a “supposed to have said.”

People chalk up quotes to Mark Twain and Churchill and Einstein all the time. That’s sorta just human nature to give these witty remarks to folk heroes famous for wisdom and smarts. The part that bothers is me is that no one, even in annual letters to investors and graduation speeches, was curious enough to be like “what was the context here for this quote I like? What was Twain saying? Where did he say it?”

It’s never been easier to find something like that out, it can be done in a few minutes. In the old days you had to walk to Cambridge and find the bookseller Bartlett, who knew every quote. Eventually Bartlett got tired of the inquiries and published a book, which is now an app.

Perhaps you’re thinking, Steve, who cares? These folks wanted to sauce their speech a little bit, does it matter? Maybe not. But as Mark Twain said, “what’s a personal website for if not working out life’s little irritants?”

Related: did Fitzgerald mean that thing about “no second acts in American lives“? Or did he conclude the exact opposite? (I’ve sometimes wondered if F. meant no second acts in the sense of like a three act Broadway play, like: American lives go right from the first act to the third act.)

June 2, 2024

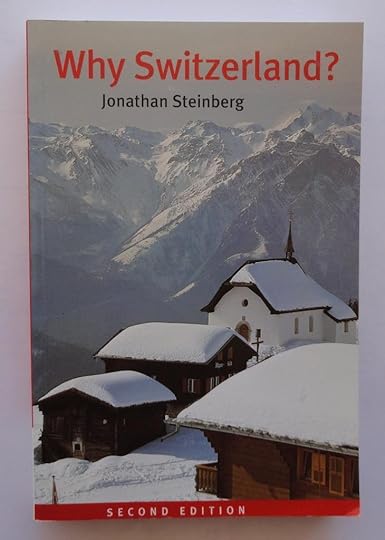

Why Switzerland? by Jonathan Steinberg

Much to admire about this book.

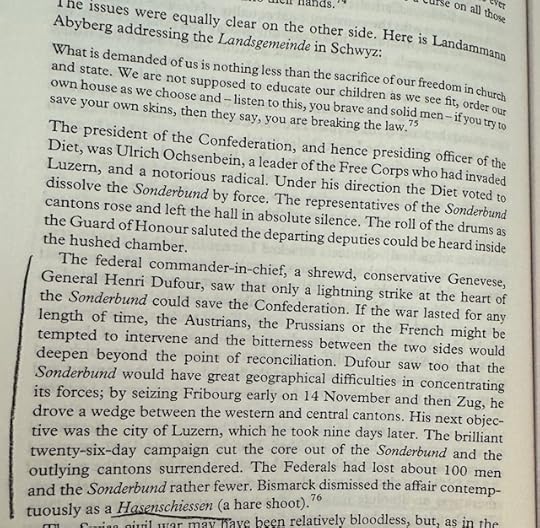

About that civil war, 1847. A group of southern cantons decided they weren’t being treated well and wanted to separate. Here’s how it went down:

(Could our civil war have ended fast too, with a lighting strike at the heart of the Confederacy? Did we dither too much because the guy at the time was the obese Winfield Scott? It seems like Lincoln pushed for that, but the debacle at Bull Run ended the hope.)

On William Tell:

Religious segregation:

Huge distinction in Swiss political organization:

This strikes me as opposite the US. In the US the weight is at the top. Presidential elections are fanatical but local elections tend to be somewhat pathetic. The US President is a big deal. The Swiss president is elected for one year and has very few powers, they’re not even the head of state, they’re just sort of a tiebreaker if necessary. Right now it’s Viola Amherd:

Bundesrätin Viola Amherd – Bern 15.12.2023 – Béatrice Devènes / Bundeskanzlei

Bundesrätin Viola Amherd – Bern 15.12.2023 – Béatrice Devènes / BundeskanzleiThere is an unwritten rule that the member of the Federal Council who has not been president the longest becomes president. Therefore, every Federal Council member gets a turn at least once every seven years. The only question in the elections that provides some tension is the question of how many votes the person who is to be elected president receives. This is seen as a popularity test.

The cover of the second edition is less spooky than the third:

Cheers to Steinberg for this valuable book full of insight.

June 1, 2024

The League of God’s House (Swiss History Part Four)

The history of Switzerland is combinations of alliances. (Is that all history?) Places (cantons) form groups to fight invasions and encroachments. From the Habsburgs, from the Burgundians, from each other. If you watched a timelapse political map of Switzerland it grows… like a cancer? Like a growth. Cells combining. Watch the flags pass by as you scroll through this one.

One answer to Steinberg’s titular question, Why Switzerland? is The Congress of Vienna. French Revolutionary armies rolled all over Switzerland, Napoleon used it as he saw fit (he seemed to find it kind of amusing and sort of admirable, and thought a federation was the natural state for the Swiss). It was not peaceful during this time. There were 21,000 Russians at the battle of Gothard Pass.

After Waterloo, when the still standing powers sorted out the future of Europe, Swiss neutrality was guaranteed.

Staying neutral, that was the hard part. In the Concise History Church and Head mention that during WWI the average Swiss guy spent 605 days deployed patrolling the border, which was tough and boring. Active duty to keep Switzerland neutral. Active neutrality. That’s another answer to Steinberg’s question Why Switzerland?: the army/national service keeps the diverse cantons bonded together.

Contemplate the following alt outcome for Europe, past or future: instead of an EU, Switzerland expands, absorbing the states around it and then the whole continent into its federal system.

*Amarco90 took that photo of Chur.

May 29, 2024

Seintology

Jerry Seinfeld was interviewed by Bari Weiss on her podcast Honestly. I listened to the whole thing. Several parts have created headlines but I thought this, towards the end, was interesting. I’ve edited this crude transcript:

Weiss:

In 1976, you took a few Scientology classes. You remember anything they taught you Tons. Like: Always confront any problem. Avoid – avoidance. Avoidance makes the problem grow and confronting it makes a shrink.

Weiss:

You’ve dabbled in Zen Buddhism. Do you have a favorite Buddhist teaching?

Seinfeld:

Yes, before enlightenment carry water and… And what’s the other thing? They do? They sweep. After Enlightenment. Carry water and sweep.

May 28, 2024

Imperial immediacy

Imperial immediacy (German: Reichsfreiheit or Reichsunmittelbarkeit) was a privileged constitutional and political status rooted in German feudal law under which the Imperial estates of the Holy Roman Empire such as Imperial cities, prince-bishoprics, and secular principalities, and such individuals as the Imperial knights, were declared free from the authority of any local lord, having no suzerain but the Holy Roman Emperor directly, without any intermediary authority: immediate = im- (negatory prefix) + mediate (in the sense of a third-party go-between, mediator); immediacy also applied to later institutions of the Empire such as the Diet (Reichstag), the Imperial Chamber of Justice and the Aulic Council.

Kemper Boyd for Wikipedia.

Kemper Boyd for Wikipedia. Trying to work out what the deal was with the counts of Annecy, or counts of Geneva who had their seat at Annecy, and the House of Savoy.

Here’s some of what Wikipedia says under “Problems Understanding the Empire:”

The practical application of the rights of immediacy was complex; this makes the history of the Holy Roman Empire particularly difficult to understand, especially for modern historians. Even such contemporaries as Goethe and Fichte called the Empire a monstrosity. Voltaire wrote of the Empire as something neither Holy nor Roman, nor an Empire, and in comparison to the British Empire, saw its German counterpart as an abysmal failure that reached its pinnacle of success in the early Middle Ages and declined thereafter.[4] Prussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke described it in the 19th century as having become “a chaotic mess of rotted imperial forms and unfinished territories”. For nearly a century after the publication of James Bryce’s monumental work The Holy Roman Empire (1864), this view prevailed among most English-speaking historians of the Early Modern period, and contributed to the development of the Sonderweg theory of the German past.[5]

A revisionist view popular in Germany but increasingly adopted elsewhere[citation needed] argued that “though not powerful politically or militarily, [the Empire] was extraordinarily diverse and free by the standards of Europe at the time”. Pointing out that people like Goethe meant “monster” as a compliment (i.e. ‘an astonishing thing’), The Economist has called the Empire “a great place to live … a union with which its subjects identified, whose loss distressed them greatly” and praised its cultural and religious diversity, saying that it “allowed a degree of liberty and diversity that was unimaginable in the neighbouring kingdoms” and that “ordinary folk, including women, had far more rights to property than in France or Spain.

Perhaps a page from the Nuremberg Chronicle will help us understand how all this worked:

Nope!