Calvin’s Geneva (Swiss History Part Five or Six)

Previous posts on Swiss history.

Jean Cauvin was a twenty-four year old lawyer and scholar when his friend/ally gave a speech at the University of Paris that was so scandalous the guy had to leave town and move to Basel. The topic of the speech? Reforming the Catholic Church.

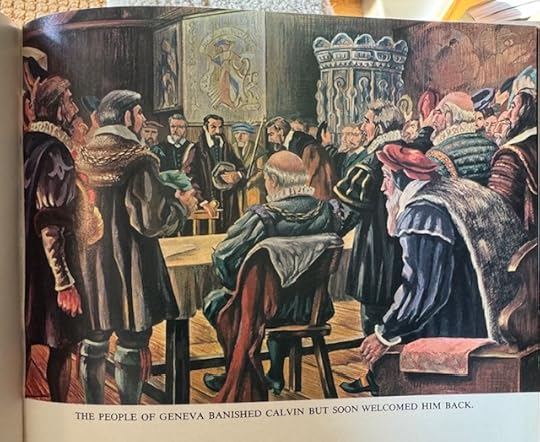

Shortly after events got so heated (y’all remember The Affair of the Placards) that Calvin had to leave town too. The Universal History of the World picks up:

The Universal History of the World, which I bought volume by volume for 50 cents each at the Needham Public Library, really fired up my youthful imagination. The book has a slight Protestant slant.

Wikipedia gives us Voltaire’s take on the reign of Calvin:

Voltaire wrote about Calvin, Luther and Zwingli, “If they condemned celibacy in the priests, and opened the gates of the convents, it was only to turn all society into a convent. Shows and entertainments were expressly forbidden by their religion; and for more than two hundred years there was not a single musical instrument allowed in the city of Geneva. They condemned auricular confession, but they enjoined a public one; and in Switzerland, Scotland, and Geneva it was performed the same as penance.”

Marilynne Robinson, in her Death of Adam, has a long essay sticking up for Calvin (she uses the spelling Cauvin):

Still, I would like to consider a little longer the strange figure of Jean Cauvin himself, because he is a true historical singularity. The theologian Karl Barth called him “a cataract, a primeval forest, something demonic, directly descending from the Himalayas, absolutely Chinese, marvelous, mythological.”

…

His commentaries on the Psalms and on Jeremiah are each about twenty-five hundred pages long in English translation, and he wrote commentary on almost the whole Bible, besides personal, pastoral, polemical, and diplomatic letters, treatises on points of doctrine, a catechism, and continuous revisions of his Institutes of the Christian Religion, the first, greatest, and most influential work of systematic theology the Reformation produced.

Robinson points out that by way of Geneva, many Protestant exiles who ended up in the future USA had an example of a republican type of government:

There are things for which we in this culture clearly are indebted to him, including relatively popular government, the relatively high status of women, the separation of church and state, what remains of universal schooling, and, while it lasted, liberal higher education, education in “the humanities.” All this, for our purposes, emanated from Geneva—in imperfect form, of course, but tending then toward improvement as it is now tending toward decline.

and:

In 1528 Geneva became an autonomous city governed by elected councils as the result of an insurrection against the ruling house of Savoy. Though the causes of the rebellion seem to have had little to do with the religious controversies of the period, in the course of it two preachers, Guillaume Farel and Pierre Viret, persuaded the city to align itself with the Reformation, then recruited Cauvin to guide the experiment of establishing a new religious culture in the newly emancipated city. That is to say, Calvinism developed with and within a civil regime of elections and town meetings…

Again, the republican institutions of Geneva were in place before Calvin set foot in that city; the Northern Netherlands freed itself and governed itself under Calvinist influence, which was strong but never exclusive; the New Englanders embraced a revolutionary order whose greatest exponents were Southerners.

She suggests we ease up on Calvin, after all he only executed the one heretic:

Bear in mind that Calvin approved the execution of only one man for heresy, the Spanish physician known as Michael Servetus, who had written books in which, among other things, he attacked the doctrine of the Trinity. One man is one too many, of course, but by the standards of the time, and considering Calvin’s embattled situation, the fact that he has only Servetus to answer for is evidence of astonishing restraint.

But she notes some difficult aspects:

Cauvin has an unsettling habit of referring to himself or to any human being as a “worm.”

I hope to learn more about John Calvin/Cauvin in Geneva. I find myself more drawn to Servetus:

Servetus also contributed enormously to medicine with other published works specifically related to the field, such as his Complete Explanation of Syrups

When Calvin died, they were worried his resting place would become a place of veneration, as for a saint, which he wouldn’t approve of, so he was buried in an unmarked grave.