Geneva Conventions (Swiss History Part Seven)

I believe this will conclude our unit on the history of Switzerland. Here you can find Part One about pre-Switzerland to the Dark Ages, Part Two about the Bernese chronicles, Part Three about founding myths like William Tell and the Rütli oath, Part Four about the various leagues up to the Congress of Vienna, Part Five about Steinberg’s Why Switzerland, and Part Six about Calvin/Cauvin’s Geneva.

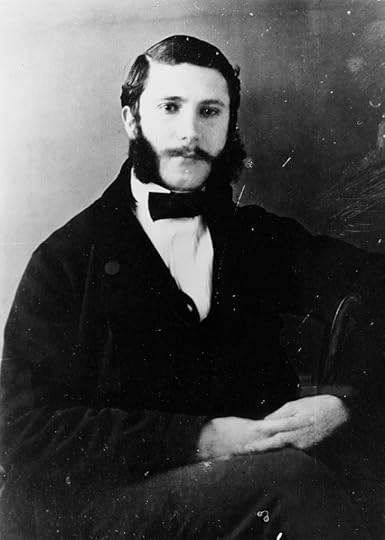

Henry Dunant was a thirty one year old Swiss businessman who was trying to arrange some deals in French-held Algeria. He was running into problems, the land and water rights were all a jumble. So he came up with a plan:

Dunant wrote a flattering book full of praise for Napoleon III with the intention to present it to the emperor, and then traveled to Solferino to meet with him personally.

Napoleon III, Emperor of France, was in a war with Austria at the time. Dunant arrived on the evening after a massive battle. There were something like 40,000 dead and wounded people around.

No one was helping them.

Shocked, Dunant himself took the initiative to organize the civilian population, especially the women and girls, to provide assistance to the injured and sick soldiers. They lacked sufficient materials and supplies, and Dunant himself organized the purchase of needed materials and helped erect makeshift hospitals. He convinced the population to service the wounded without regard to their side in the conflict as per the slogan “Tutti fratelli” (All are brothers) coined by the women of nearby city Castiglione delle Stiviere. He also succeeded in gaining the release of Austrian doctors captured by the French and British.

When he got home, he wrote up a book called A Memory of Soferino, in which he described what he saw and set forth the idea that a neutral organization that could help the wounded in war would be valuable.

On February 7, 1863, the Société genevoise d’utilité publique [Geneva Society for Public Welfare] appointed a committee of five, including Dunant, to examine the possibility of putting this plan into action. With its call for an international conference, this committee, in effect, founded the Red Cross.

That’s from the Nobel Prize website; Dunant won the first ever Nobel Peace Prize.

A year after the founding of the Red Cross, the government of Switzerland invited all European countries as well as the US, Mexico and Brazil to a conference where they agreed on the first Geneva Convention “for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field”. They met in the Alabama room of Geneva’s city hall. Now, why was it called the Alabama room? Because that’s where an international tribunal met to work out the Alabama Claims, an international dispute between the US and the UK regarding grievances over Confederate raiders, including the Alabama, which were built in the UK and used against the US.

The Alabama.

So, Geneva already had a rep as a place for international meetings.

As for Dunant, he went bust. Says Nobel Prize.org:

After the disaster, which involved many of his Geneva friends, Dunant was no longer welcome in Genevan society. Within a few years he was literally living at the level of the beggar. There were times, he says, when he dined on a crust of bread, blackened his coat with ink, whitened his collar with chalk, slept out of doors.

For the next twenty years, from 1875 to 1895, Dunant disappeared into solitude. After brief stays in various places, he settled down in Heiden, a small Swiss village. Here a village teacher named Wilhelm Sonderegger found him in 1890 and informed the world that Dunant was alive, but the world took little note. Because he was ill, Dunant was moved in 1892 to the hospice at Heiden. And here, in Room 12, he spent the remaining eighteen years of his life. Not, however, as an unknown. After 1895 when he was once more rediscovered, the world heaped prizes and awards upon him.

Despite the prizes and the honors, Dunant did not move from Room 12. Upon his death, there was no funeral ceremony, no mourners, no cortege. In accordance with his wishes he was carried to his grave «like a dog»3.

The Red Cross calls me just about every day about giving blood. I’ve got to do that again.