Steve Hely's Blog, page 12

August 30, 2024

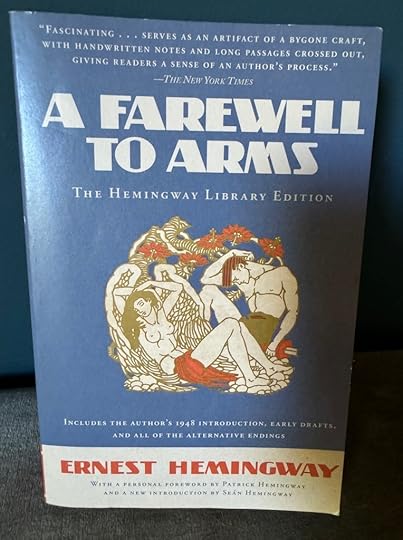

A Farewell To Arms (1929)

serves as an artifact of a bygone craft

says a quote (NY Times) on the cover of my Hemingway Library copy. I believe that’s referring to this specific edition which includes a lot of Hemingway’s revisions and alternate drafts, but can we escape the idea that maybe the novel itself is a bygone craft?

I saw that the novel, which at my maturity was the strongest and supplest medium for conveying thought and emotion from one human being to another, was becoming subordinated to a mechanical and communal art that, whether in the hands of Hollywood merchants or Russian idealists, was capable of reflecting only the tritest thought, the most obvious emotion. It was an art in which words were subordinate to images, where personality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration. As long past as 1930, I had a hunch that the talkies would make even the best selling novelist as archaic as silent pictures.

so said Fitzgerald, Hemingway frenemy and penis-measuring subject in The Crack-Up.

A Farewell To Arms was made into two different movies. I haven’t seen either of them but I’ve watched the trailers on YouTube and they both appear kinda lame, missing the essence, which comes from the point of view and the style.

This might be the most famous passage from AFTA:

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain. We had heard them, sometimes standing in the rain almost out of earshot, so that only the shouted words came through, and had read them, on proclamations that were slapped up by billposters over other proclamations, now for a long time, and I had seen nothing sacred, and the things that were glorious had no glory and the sacrifices were like the stockyards at Chicago if nothing was done with the meat except to bury it. There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

Concrete names are a big feature of the book: Udine, Campoformio, Tagliamento, Cividale, Caporetto. I read the book with a map of Italy at hand but doesn’t it work without it? Near the climax when Frederick Henry must row with Catherine to Switzerland to escape the war he’s given this instruction:

Past Luino, Cannero, Cannobio, Tranzano. You aren’t in Switzerland until you come to Brissago. You have to pass Monte Tamara.

More:

“If you row all the time you ought to be there by seven o’clock in the morning.”

“Is it that far?”

“It’s thirty-five kilometres.”

“How should we go? In this rain we need a compass.”

“No. Row to Isola Bella. Then on the other side of Isola Madre with the wind. The wind will take you to Pallanza. You will see the lights. Then go up the shore.’

“Maybe the wind will change.”

“No,” he said. “This wind will blow like this for three days. It comes straight down from the Mattarone. There is a can to bail with.”

“Let me pay you something for the boat now.”

“No, I’d rather take a chance. If you get through you pay me all you can.”

“All right.”

“I don’t think you’ll get drowned.”

“That’s good.”

“Go with the wind up the lake.”

“All right.” I stepped in the boat.

“Did you leave the money for the hotel?”

“Yes. In an envelope in the room.”

“All right. Good luck, Tenente.”

“Good luck. We thank you many times.”

“You won’t thank me if you get drowned.”

On this read I considered the advice Hemingway gave to Maestro:

MICE: How can a writer train himself?

Y.C.: Watch what happens today. If we get into a fish see exact it is that everyone does. If you get a kick out of it while he is jumping remember back until you see exactly what the action was that gave you that emotion. Whether it was the rising of the line from the water and the way it tightened like a fiddle string until drops started from it, or the way he smashed and threw water when he jumped. Remember what the noises were and what was said. Find what gave you the emotion, what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling you had. Thatʼs a five finger exercise.

Plug that into the scene where Henry gets wounded:

“This isn’t a deep dugout,” Passini said.

“That was a big trench mortar.”

“Yes, sir.”

I ate the end of my piece of cheese and took a swallow of wine.

Through the other noise I heard a cough, then came the chuh-chuhchuh-chuh-then there was a flash, as when a blast-furnace door is swung open, and a roar that started white and went red and on and on in a rushing wind. I tried to breathe but my breath would not come and I felt myself rush bodily out of myself and out and out and out and all the time bodily in the wind. I went out swiftly, all of myself, and I knew I was dead and that it had all been a mistake to think you just died. Then I floated, and instead of going on I felt myself slide back. I breathed and I was back. The ground was torn and in front of my head there was a splintered beam of wood.

In the jolt of my head I heard somebody crying. I thought somebody was screaming. I tried to move but I could not move. I heard the machine-guns and rifles firing across the river and all along the river. There was a great splashing and I saw the star-shells go up and burst and float whitely and rockets going up and heard the bombs, all this in a moment, and then I heard close to me some one saying “Mama Mia! Oh, mama Mia!” I pulled and twisted and got my legs loose finally and turned around and touched him. It was Passini and when I touched him he screamed.

Much of the book mirrors Hemingway’s own experience, but in kind of a juiced up way. Hemingway was wounded in the war, but he was an ambulance driver with the Red Cross. Henry is a lieutenant in the Italian army. (Why? “I was in Italy.”) Hemingway has promoted himself. Hemingway in real life had an affair with a nurse, who then broke things off while Hemingway was back in Chicago. (An apparently close to biographical facts version of this story is told by Hemingway in “A Very Short Story.”) In the AFTA version, the nurse falls in love with Henry, escapes with him, is going to have his baby.

The most vivid part of the book is the retreat from Caporetto. Hemingway wasn’t at the retreat from Caporetto, but he’d heard about it.

In Italy when I was at the war there, for one thing that I had seen or that had happened to me, I knew many hundreds of things that had happened to other people who had been in the war in all of its phases. My own small experiences gave me a touchstone by which I could tell whether stories were true or false and being wounded was a password.

I’m reminded of Mike White telling Marc Maron that he tried to make a version of himself that exaggerated his flaws, leaning into his awkward, uncomfortable self, to make Chuck & Buck. Then he saw Good Will Hunting and saw that Matt Damon and Ben Affleck had made versions of themselves that were cooler, better, good with kids, getting in fights, exaggeratedly great.

There’s a part of A Farewell to Arms where Tenente Henry rates his own courage:

“They won’t get us,” I said. “Because you’re too brave. Nothing ever happens to the brave.”

“They die of course.”

“But only once.”

“I don’t know. Who said that?”

“The coward dies a thousand deaths, the brave but one?”

“He was probably a coward,” she said. “He knew a great deal of them perhaps.”

“I don’t know. It’s hard to see inside the head of the brave”

“Yes. That’s how they keep that way.”

“You’re an authority.”

“You’re right, darling. That was deserved.”

“You’re brave.

“No,” she said. “But I would like to be.”

“I’m not,” I said. “I know where I stand. I’ve been out long enough to know. I’m like a ball-player that bats two hundred and thirty and knows he’s no better.”

“What is a ball-player that bats two hundred and thirty? It’s awfully impressive.”

“It’s not. It means a mediocre hitter in baseball.”

“But still a hitter,” she prodded me.

“I guess we’re both conceited,” I said. “But you are brave.”

“No. But I hope to be.”

“We’re both brave,” I said. “And I’m very brave when I’ve had a drink.”

A funny part is how many liquor bottles Miss Van Campen finds in Henry’s hospital room:

“Miss Gage looked. They had me look in a glass. The whites of the eyes were yellow and it was the jaundice. I was sick for two weeks with it. For that reason we did not spend a convalescent leave together. We had planned to go to Pallanza on Lago Maggiore. It is nice there in the fall when the leaves turn. There are walks you can take and you can troll for trout in the lake. It would have been better than Stresa because there are fewer people at Pallanza. Stresa is so easy to get to from Milan that there are always people you know. There is a nice village at Pallanza and you can row out to the islands where the fishermen live and there is a restaurant on the biggest island. But we did not go.

One day while I was in bed with jaundice Miss Van Campen came in the room, opened the door into the armoire and saw the empty bottles there. I had sent a load of them down by the porter and I believe she must have seen them going out and come up to find some more. They were mostly vermouth bottles, marsala bottles, capri bottles, empty chianti flasks and a few cognac bottles.

The porter had carried out the large bottles, those that had held vermouth, and the straw-covered chianti flasks, and left the brandy bottles for the last. It was the brandy bottles and a bottle shaped like a bear, which had held kümmel, that Miss Van Campen found.

The bear-shaped bottle enraged her particularly. She held it up, bear was sitting up on his haunches with his paws up, there was a cork in his glass head and a few sticky crystals at the bottom. I laughed.

“It is kümmel,” I said. “The best kümmel comes in those bearshaped bottles. It comes from Russia.”

“Those are all brandy bottles, aren’t they?” Miss Van Campen asked.

“I can’t see them all,” I said. “But they probably are.”

“How long has this been going on?”

“I bought them and brought them in myself,” I said. “I have had Italian officers visit me frequently and I have kept brandy to offer them.’

“You haven’t been drinking it yourself?” she said.

“I have also drunk it myself.”

“Brandy,” she said. “Eleven empty bottles of brandy and that bear liquid.”

“Kümmel.”

“I will send for some one to take them away. Those are all the have?”

“For the moment.”

“And I was pitying you having jaundice. Pity is something that is wasted on you.”

“Thank you.”

(On this reading of the book it was clear that part of why Miss Van Campen is such a priss is she was horny for Henry and upset that he already had a girlfriend.)

Good times in Milan:

Afterward when I could get around on crutches we went to dinner at Biffi’s or the Gran Italia and sat at the tables outside on the floor of the galleria. The waiters came in and out and there were people going by and candles with shades on the tablecloths and after we decided that we liked the Gran Italia best, George, the head-waiter, saved us a table. He was a fine waiter and we let him order the meal while we looked at the people, and the great galleria in the dusk, and each other. We drank dry white capri iced in a bucket; although we tried many of the other wines, fresa, barbera and the sweet white wines. They had no wine waiter because of the war and George would smile ashamedly when I asked about wines like fresa.

“If you imagine a country that makes a wine because it tastes like strawberries,” he said.

“Why shouldn’t it?” Catherine asked. “It sounds splendid.”

“You try it, lady,” said George, “if you want to. But let me bring a little bottle of margaux for the Tenente.”

Biffi’s is still there, it’s not highly rated.

Abruzzo mentioned:

It was dark in the room and the orderly, who had sat by the foot of the bed, got up and went out with him. I liked him very much and I hoped he would get back to the Abruzzi some time. He had a rotten life in the mess and he was fine about it but I thought how he would be in his own country. At Capracotta, he had told me, there were trout in the stream below the town. It was forbidden to play the flute at night. When the young men serenaded only the flute was forbidden. Why, I had asked. Because it was bad for the girls to hear the flute at night. The peasants all called you “Don” and when you met them they took off their hats. His father hunted every day and stopped to eat at the houses of peasants. They were always honored. For a foreigner to hunt he must present a certificate that he had never been arrested. There were bears on the Gran Sasso D’Italia but it was a long way. Aquila was a fine town. It was cool in the summer at night and the spring in Abruzzi was the most beautiful in Italy. But what was lovely was the fall to go hunting through the chestnut woods. The birds were all good because they fed on grapes and you never took a lunch because the peasants were always honored if you would eat with them at their houses.”

At one point in the book the narrator is literally side-tracked: his train is diverted to a side track and stopped. The term “sidetracked” I have often heard in writers’ rooms to mean “going off in a side direction,” negative connotation. In the original usage it seems to have meant going nowhere, stopped.

The reason why I reread this book, which I hadn’t looked at since high school: towards the end Henry and Catherine take refuge in Montreux, Switzerland. We were going to Montreux and I wanted to hear what Hemingway had to say about it:

Sometimes we walked down the mountain into Montreux.

There was a path went down the mountain but it was steep and so usually we took the road and walked down on the wide hard road between fields and then below between the stone walls of the vineyards and on down between the houses of the villages along the There were three villages; Chernex, Fontanivent, and the other I forget. Then along the road we passed an old square-built stone château on a ledge on the side of the mountain-side with the terraced fields of vines, each vine tied to a stick to hold it up, the vines dry and brown and the earth ready for the snow and the lake down below flat and gray as steel. The road went down a long grade below the château and then turned to the right and went down very steeply and paved with cobbles, into Montreux.

We did not know any one in Montreux. We walked along beside the lake and saw the swans and the many gulls and terns that flew you came close and screamed while they looked down at when the water. Out on the lake there were flocks of grebes, small and dark, and leaving trails in the water when they swam.

In the town we walked along the main street and looked in the windows of the shops. There were many big hotels that were closed but most of the shops were open and the people were very glad to see us. There was a fine coiffeur’s place where Catherine went to have her hair done. The woman who ran it was very cheerful and the only person we knew in Montreux. While Catherine was there I went up to a beer place and drank dark Munich beer and read the papers. I read the Corriere della Sera and the English and American papers from Paris. All the advertisements were blacked out, supposedly to prevent communication in that way with the enemy. The papers were bad reading. Everything was going very badly everywhere.

How much would Hemingway recognize today’s Montreux, the jazz festival Montreux, Deep Purple/Freddie Mercury/Russian emigre Montreux?

Maybe parts of the old town:

Here is a discussion question (contains a spoiler):

The end of the book is often presented as tragic. Catherine has died giving childbirth. Henry walks alone into the rain. But, is there a very cynical reading that this is actually a relief for Henry? From when he first met Catherine he suspected she might be “crazy.” Now the encumbrance of this woman and a baby he didn’t really want is lifted. Not only that he’s granted a pleasing tragedy to be sentimental about. Is this a male fantasy ending? All the credit, none of the work?

Recall the title of James Mellow’s biography of Hemingway: “A Life Without Consequences.” Is that the fantasy here? The only consequence is valuable experience, worldliness.

As usual with Hemingway the line between sentimental, romantic, and hardboiled, cynical is quite thin.

August 27, 2024

Reece Duca: fanatically reliant

Bob Casey: You talk about the fact that there are a very small number of really exceptional companies. What do you mean by that?

Reece Duca: I rely on a study from–I believe his name’s Hendrick Bessembinder from Arizona State University– and what he did is he looked at every single public company from 1926 to 2016. So he covered a 90 year period. There were a total of 26,000 companies. And of the 26,000 companies, 25 of the 26,000 companies produced returns that are T-bill returns or less. So in other words, there was only 1000 companies that could create excess returns above risk-free T-bills returns.

Now you look at public companies, and you realize that companies can come public and because there’s a lot of incentives in the market, from whoever the constituent is, that their shareholders, their private equity holders, the investment bankers, whatever, you bring the companies public, but how many of them are exceptional companies? How many of them–and the reality is, most of them end up falling into that bucket that Professor Kay said, That’s the gray bucket. That’s the bucket of which, essentially, it’s the efficient market bucket.

And so, there’s only a tiny number of exceptional companies. And you understand that there’s some very specific things that permit exceptional companies to be sustainable decade after decade after decade. And many, many of them have to do with getting to the point where your customers are fanatically reliant, whether it’s a consumer product or whether it’s a business product, but your customers are fanatically reliant on what you deliver to them. If it’s a consumer product, it’s somebody is hooked on Coke, and they’re gonna drink coke come hell or high water. If it’s a business product, it gets locked into the workflow of the business, it’s something that your customers are ecstatic about. And that just essentially codified to us that what we needed to do, if we were going to have concentrated positions, we basically had to have super, super high confidence. And you had to find exceptional companies.

source. I was up in Santa Barbara so naturally reading about the local investment titan.

August 25, 2024

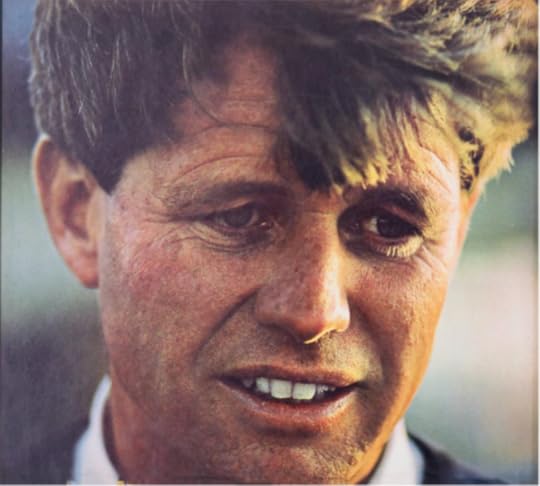

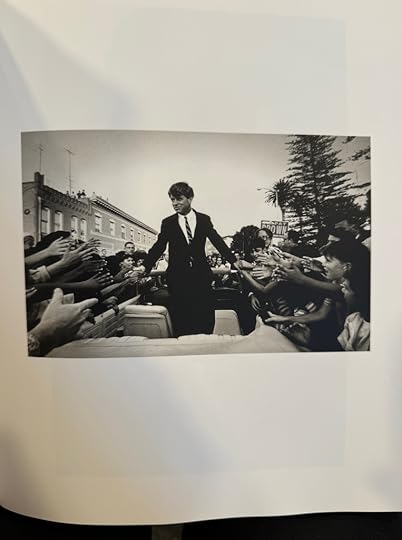

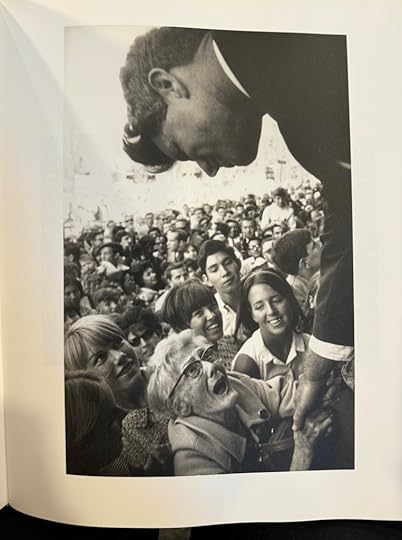

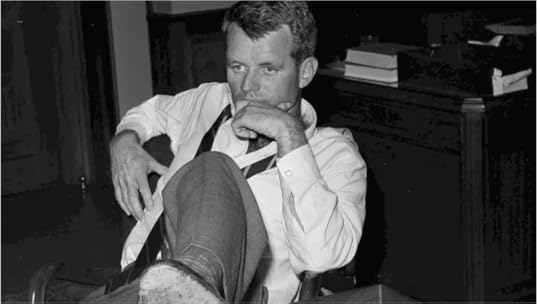

Glimpses of Robert F. Kennedy (Senior)

(source: MO 2021.4.249 at the JFK Library)

from Herb Caen’s column, January 5, 1968:

At 12:45 p.m. on Wednesday, Senator Robert F. Kennedy was standing curbside on Sacramento St. near Montgomery, dripping charisma all over the place. He was chatting with two of his henchmen (Democrats have henchmen, Republicans have aides) and his mere presence had an electrifying effect. Motorists slowed down to gape at him. A chubby, giggling Japanese waitress emerged from a coffee shop to wait, shivering, for an autograph.

An elderly Japanese in a black overcoat asked for one, too (you know how these Easterners stick together). Four men emerging from the Red Knight suddenly stopped, transfixed, to stare at him as they picked their teeth with toothpicks. The Senator glanced at them with a tentative smile. They moved on, still picking their teeth.

“Lunch,” he said, jaywalking toward Jack’s with a young henchman, Peter Edelman. We went upstairs to Private Dining Room One, a one-windowed cubicle barely big enough for three. The Senator-it’s hard to refrain from calling him “Bobby” although his friends call him “Bob” —stared at the buzzer on the wall. “To summon the girls,” I said. He looked nervous till I explained that it USED to be possible to take girls upstairs at Jack’s. “Now then,” I went on, “let’s light up cigars and nominate a Vice-President” (I forgot to tell you, I’m great fun at parties). He smiled a tiny one. The waiter whispered nervously in my ear: “How do I address him?” “Senator,” I whispered back. “Sir,” said the waiter, clearing his throat, “would you like a drink?” The Senator ordered a beer-“Coors.” …

In casual conversation, the celebrated toughness isn’t apparent. In 90 minutes, he made only one bitter remark—while talking about an Air Force decision (made over McNamara’s objec-tions) that cost us nine planes in Vietnam. He went on to the “futil-ity® of bombing North Vietnam, and recalled how, during World War II, German production had actually increased under heavy bombing. “The Air Force,” he snapped, “is never right.”…

We ordered fresh cracked crab. “This is wonderful,” he enthused.

With a glance out the window: “What a beautiful city.” Helping himself to more mayonnaise: “I could sit here all afternoon, eating cracked crab.” He asked about Joe Alioto and (a note of concern here how Eugene McCarthy is doing in California, but he wouldn’t be drawn out on the subject. Hunters Point came up and I mentioned that Eastern newsmen were always saying that our slums are garden spots compared to theirs. He nodded: “It’s better to be poor in San Francisco than rich in New York.”

“If the war is still on when your oldest son reaches the draft age,” I said, “what will you tell him?” He took evasive action. “Well, we’d talk about it, all about it, and then I guess it would be his deci-sion.” Then he told, with apparent approval, an anecdote about a friend of his who had been “a terrific hawk” before he went to Viet-ham and who is now “a terrific dove.” “He has an 18-year-old son,” Kennedy went on, “and he told me ‘If that kid doesn’t burn his draft card, I’ll do it for him!'”

***

We stepped outside and he was immediately engulfed by auto-graph-seekers. “Senator,” somebody called out, “your helicopter is waiting”— just like in the movies, and he drove away with a wave and that shy smile. Would I vote for him for President? Well, a man who likes our cracked crab and thinks it’s better to be poor in San Francisco than rich in New York …

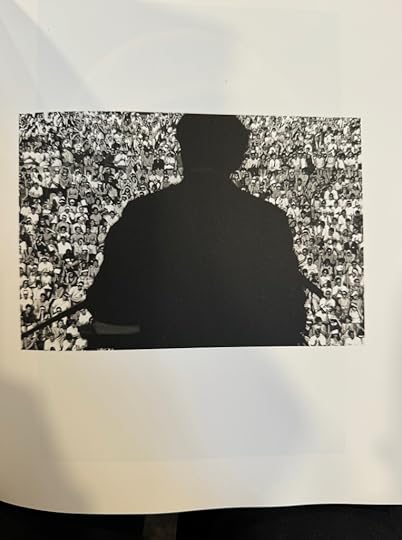

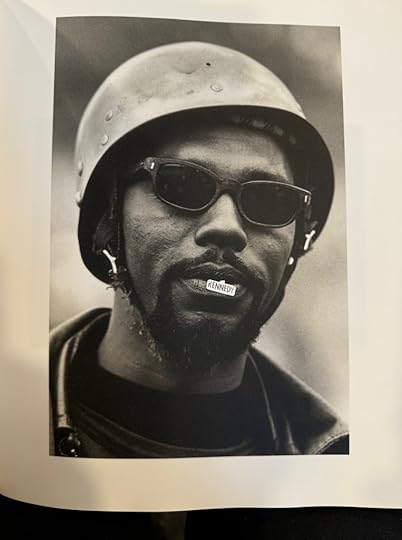

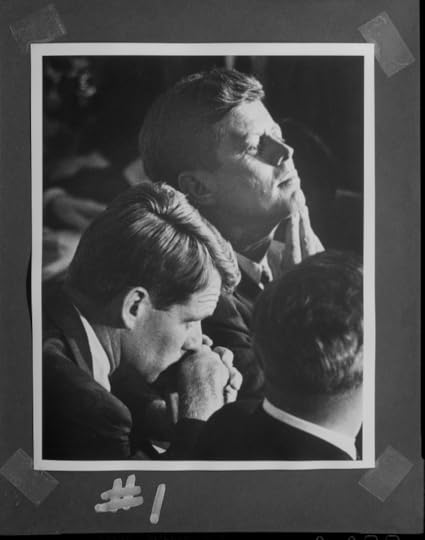

Steve Shapiro took these photos:

They’re sometimes cited as being from RFK’s presidential campaign, but the one above is from a 1966 trip to California, where he did some campaigning with Pat Brown.

That one New York, Senate campaign.

I found them in Shapiro’s book, American Edge.

California again. That must be the Berkeley Greek Theater. Here’s how The New York Times reported on that speech (front page):

Screenshot

Screenshot

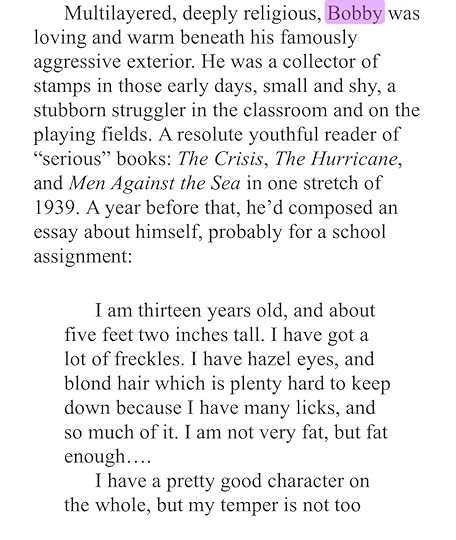

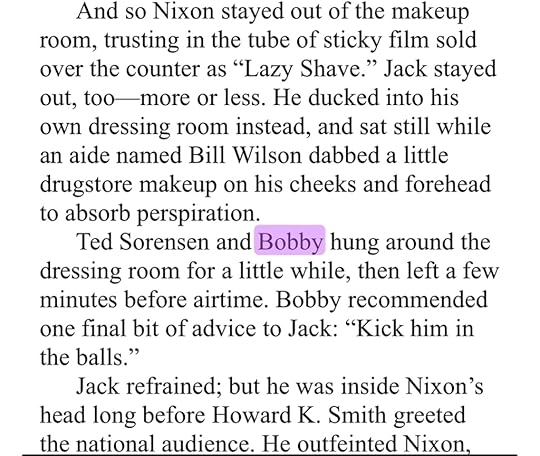

From Ted Kennedy’s memoir True Compass:

(source)

from a Miller Center interview with Reagan campaign aide Stuart Spencer in November, 2001:

I did a thing at Annenberg School last week. It’s a journalism school at University of Southern California communications center. Ed Guttman is involved with it. He was one of Bobby’s guys, and he was there that night. I said to Ed, Maybe you don’t want to answer this question, but one thing that’s always in my mind: politically, why did Bobby, once he became Attorney General, decide to go after the people his father had put together to finance some of this effort? It was a lot of the hoods and Chicago guys that he’d done business with when he was a bootlegger. There’s been references to it, but did Bobby not know that this transpired? Or did Bobby say to his dad, The hell with it, this is good politics. The hell with it—I believe this—these are bad people. He went right to the heart of what thirty years before were Joe Kennedy’s business associates.

There are conspiracy theories out there that cost him his life. I don’t know if they’re true or not, but God, that’s a fascinating triangle. He wouldn’t answer the question. He said, I don’t know what you’re talking about. I’ve never seen that before in our life. It’s like you have the support of the National Rifle Association or the National Environmental Council and you get into power and you gut them. I’ve never seen that before. But he went after them tooth and toenail.

(source: https://www.loc.gov/item/98509265/ )

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger, Bobby Western talks to his lawyer, Kline. Kline gets going on the Kennedys (the bold is mine, long but intriguing):

You didnt have some connection with the Kennedys.

No.

I worked with Bobby in Chicago in the early sixties. Briefly. We were working with a guy named Ed Hicks who was trying to get free elections for the Chicago cabdrivers. Basically Kennedy was a mor-alist. Before long he was to have an amazing roster of enemies and he prided himself on knowing who they were and what they were up to. Which he didnt, of course. By the time his brother was shot a couple of years later they were mired up in a concatenation of plots and schemes that will never be sorted out. At the head of the list was killing Castro and if that failed actually invading Cuba. In the end I dont think that would have happened but it’s a sort of bellwether for all the trouble they were in. I always wondered if there might not have been a moment there when Kennedy realized he was dying that he didnt smile with relief. After old man Kennedy had his stroke the Kennedys for some reason felt that it would be all right to go after the Mafia. Ignoring the longstanding deal the old man had cut with them. No idea what they were thinking. All the time Jack is schtupping Sam Giancana’s girl-friend—a lady named Judith Campbell. Although in all fairness-quaint term—I think that Jack saw her first. Or one of his pimps did. Some guy named Sinatra.

What are you going to say about the Kennedys? There’s no one like them. A friend of mine was at a houseparty out on Martha’s Vineyard one evening and when he got to the house Ted Kennedy was greeting people at the door. He was dressed in a bright yellow jumpsuit and he was drunk.

My friend said: That’s quite an outfit you’ve got on there, Senator. And Kennedy said yes, but I can get away with it. My friend-who’s a Washington lawyer-told me that he had never understood the Ken-nedys. He found them baffling. But he said that when he heard those words the scales fell from his eyes. He thought that they were probably engraved on the family crest. However you say it in Latin. Anyway, I’ve never understood why there is no monument anywhere to Mary Jo Kopechne. The girl Ted left to drown in his car after he drove it off a bridge. If it were not for her sacrifice that lunatic would have been President of the United States. My guess is that with the exception of Bobby they were just a pack of psychopaths. I suppose it was Bobby’s hope that he could somehow justify his family. Even though he must have known that was impossible. There wasnt a copper cent in the coffers that funded the whole enterprise that wasnt tainted. And then they all died.

Murdered, for the most part. Maybe not Shakespeare. But not bad Dostoevsky.

Castro was no part of this.

No. In the end as it turned out he wasnt.

When he took over the island he threw Santo Trafficante in jail and told him that he was going to be shot as an enemy of the people. So of course Trafficante just said:

How much? You hear different figures. Forty million. Twenty million. It was probably closer to ten. But Trafficante wasnt happy about it. The Mafia had a long history of running the casinos for Ba-tista. Castro should have treated them bet-ter. The Mafia. He’s lucky to be alive. The odd thing is that Santo ran three casinos in Cuba for another eight or ten years after that. Language is important. People forget that Trafficante’s first language is Spanish.

Anyway, he and Marcello have run the Southeast from Miami to Dallas for years.

And the net worth of this enterprise is staggering. At its height over two billion a year. Bobby Kennedy wouldnt have deported Marcello without Jack’s okay, but by now the whole business was beyond disentanglement. The CIA hated the Ken-nedys and were working at cutting themselves loose from the administration al-together, but the notion that they killed Kennedy is stupid. And if Kennedy was going to take the CIA apart piece by piece as he promised to do he’d have had to start about two administrations sooner. By his time it was way too late. The CIA hated Hoover too and Hoover in turn hated the Kennedys and people just assumed that Hoover was in bed with the Mafia but the truth was the Mafia had endless files of Hoover as a transvestite-dressed in ladies’ underwear-so that was a Mexican standoff that had been in play for years.

There’s more to it of course. But if you said that Bobby had gotten his brother-whom he adored —killed, I would have to say that was pretty much right. The CIA hauled Carlos off to the jungles of Guatemala and flew away waving back at him. Hard to imagine what they were thinking. They left him there-where he held a counterfeit passport-and his lawyer finally showed up and then the two of them were frogmarched off into the jungles of El Salvador and left to fashion new lives for them-selves. Standing there in the heat and the mud and the mosquitoes. Dressed in wool suits. They hiked some twenty miles until they came to a village. And, God be praised, a telephone. When he got back to New Orleans he called a meeting at Churchill Farms-his country place-and he was foaming at the mouth over Bobby Kennedy. He looked at the people in the room-I think there were eight of them-and he said: I’m going to whack the little bastard. And it got very quiet. Everybody knew it was a serious meeting. There was nothing on the table to drink but water.

And finally somebody said: Why dont we whack the big bastard? And that was that.

I’m not sure I understand.

If you killed Bobby then you had a really pissed off JFK to deal with. But if you killed JFK then his brother went pretty quickly from being the Attorney General of the United States to being an unemployed lawyer.

How do you know all this?

Right. The thing about the Kennedys was that they had no way to grasp the in-appeasable war-ethic of the Sicilians. The Kennedys were Irish and they thought that you won by talking. They didnt really even understand that this other thing existed. They used abstractions to make political speeches. The people. Poverty. Ask not what your country blah blah blah.

They didnt understand that there were still people alive who actually believed in things like honor. They’d never heard Joe Bonanno on the subject. That’s what makes Kennedy’s book so preposterous.

Although in all fairness there’s some question as to whether or not he ever even read it. I’m having the chicken grande.

All right.

You want to pick the wine?

Sure.

Michael Herr talking about the Kennedys in Las Vegas in The Big Room;

Because even then his kid brother was around like a mongoose on Benzedrine, watching, keeping tabs and running the connections down to their root-ends, to see exactly who was friends with who, and who to play up, or down, or chop completely. The older brother’s playground was the younger brother’s nightmare. Still, the action was invigorating. It’s possible that more of the New Frontier was inspired here at the Sands than back on the Massachusetts bedrock or looking dreaming out of the office window at the Jefferson Memorial.

One more from Brother Edward:

August 24, 2024

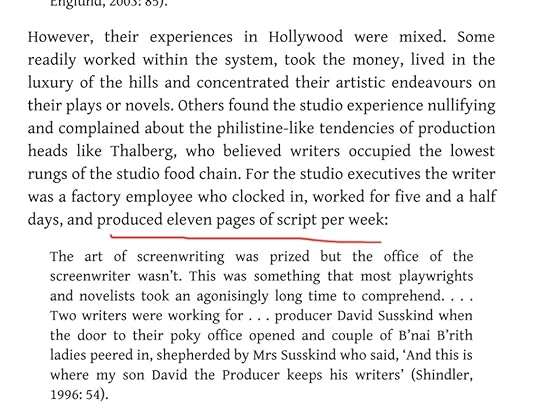

Eleven pages a week

In one of my Hollywood books I read that writers in the studio system were expected to write eleven pages a week.

Eleven pages, seems very reasonable. Especially if we are talking script pages which have a lot of white on them.

Now you may have to write thirty-three pages to produce eleven good ones, but still.

I went looking for where I found this information but I couldn’t locate it in Schatz, Genius of the System, or Friedfrich, City of Nets, or Thomson, The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood, or Behlmer, Memo from David O. Selznick, or Pirie, Anatomy of the Movies, or Rosen, Hollywood, or Dardis, Some Time in the Sun, or Powdermaker, Hollywood: The Dream Factory or even Solomon, William Faulkner The Screenwriter. Not to say it’s in one of those, I just couldn’t retrieve it.

Using a Google Books search I did find reference to an eleven pages expectation:

That’s in Mark Wheeler, Hollywood: Politics and Society, which I’ve never read.

Cool cover!

If you reliably produce eleven pages a week your odds at some success are high.

Eleven pages a week will be my goal when I return from vacation at the end of August.

(that Faulkner typing pic seems to be from Time-Life Getty Images, found it on Reddit).

August 18, 2024

Reedy, Twilight of the Presidency

It’s time to revisit George Reedy, Twilight of the Presidency.

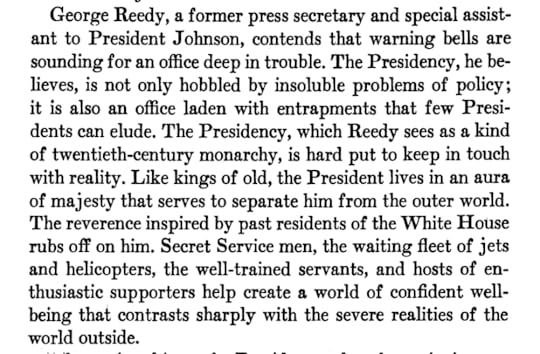

I can’t do better as a summary than this 1970 review by William C. Spragens in The Western Political Quarterly found on JSTOR:

The edition I read is updated for the Reagan administration. Some choice passages:

In talking to friends about the presidency, I have found the hardest point to explain is that setbacks often impel presidents to redouble their efforts without changing their policies. This seems to be perversity because very few of us have the opportunity to make decisions of colossal consequences. When our projects go wrong, it is not too difficult for most of us to shrug our shoulders, cut our losses, and take off on a new tack. Our egos may be bruised. But we can live with that. It is a different thing altogether when we can give orders that can lead to large-scale death and destruction or even to economic devastation. Such a situation brings into play psychological factors that are virtually unconquerable.

Suppose, for example, that a president gives the military an order that leads to the deaths of several soldiers in combat. Can any human being who did such a thing say to himself: “Those men are dead because I was a God-damned fool! Their blood is on my hands.” The likely thought is: “Those men died in a noble cau and we must see to it that their sacrifice was not in vain.”

This, of course, could well be the “right” answer. But even if it is the wrong answer, it is virtually certain to be the one that will be accepted. Therefore, more men are sent and then more and then more. Every death makes a pull out more unacceptable.

Furthermore, when a large amount of blood has been spilled, a point can be reached where popular opposition to a policy will actually spur a president to redoubled effort in its behalf. This is due to the aura of history that envelops every occupant of the Oval Office. He lives in a museum, a structure dedicated to preserving the greatness of the American past. He walks the same halls paced by Lincoln waiting feverishly for news from Gettysburg or Richmond. He dines with silver used by Woodrow Wilson as he pondered the proper response to the German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. He has staring at him constantly portraits of the heroic men who faced the same excruciating problems in the past that he is facing in the present. It is only a matter of time until he feels himself a member of an exclusive community whose inhabitants never finally leave the mansion. When stories leaked out that Richard Nixon was “talking to the pictures” in the White House, it was taken by many as evidence that he was cracking up. To anyone who has had the opportunity to observe a president at close range, it is perfectly normal conduct.

(This may be a problem beyond presidents. Do we all have a tendency to double down on our most consequential decisions, even if the results are obviously disastrous?)

The life of the monarch:

As noted, an essential characteristic of monarchy is untouchability. No one touches a king unless he is specifically invited to do so. No one thrusts unpleasant thoughts upon a king unless he is ordered to do so, and even then he does so at his own peril. The response to unpleasant information has been fixed by a pattern with a long history. Every courtier recalls, either literally or instinctively, what happened to the messenger who brought Peter the Great the news of the Russian defeat by Charles XII at the Battle of Narva. The courtier was strangled by decree of the czar. A modern-day monarch-at least a monarch in the White House-cannot direct the placing of a noose around a messenger’s throat for bringing him bad news. But his frown can mean social and economic strangulation. Only a very brave or a very foolish person will suffer that frown.

Some ways in which this effect takes shape:

In retrospect, it is almost impossible to believe that John Kennedy embarked on the ill-fated Bay of Pigs venture. It was poorly conceived, poorly planned, poorly executed, and undertaken with grossly inadequate knowledge. But anyone who has ever sat in on a White House council can easily deduce what happened without knowing 34 THE I any facts other than those which appeared in the public press. White House councils are not debating matches in which ideas emerge from the heated exchanges of participants. The council centers around the president, himself, to whom everyone addresses his observations.

The first strong observations to attract the favor of the president become subconsciously the thoughts of everyone in the room. The focus of attention shifts from a testing of all concepts to a groping for means of overcoming the difficulties. A thesis that could not survive an undergraduate seminar in a liberal arts college becomes accepted doctrine, and the only question is not whether it should be done but how it should be done.

Reedy on White House aides as courtiers, and how Vietnam could’ve happened (he was there!):

Unfortunately, the problem is far deeper than the machinations of courtiers. They do exist in large numbers but most of their energies are absorbed in grabbing for personal favors and building havens of retreat for the future. Generally speaking, they play the role in the White House of the court jesters of the Middle Ages and may even be useful in that they give the chief executive badly needed relaxation. Paradoxically , it is the advisers who are not sycophantic, who are not looking for snug harbors, and who do feel the heavy weight of responsibility who are the most likely to play the reinforcing role. It is precisely because they recognize the ultimacy of the office that they react the way they do.

However they feel, the burden of decision is on another man. Therefore, however much they may argue against a policy at its beginning stages, once it is set they become “good soldiers” and devote their time to making it work.

Those who disagree strongly tend to remain in the structure in the vain hope they can change it coupled with the certainty that they would become totally ineffectual if they left.

This is the bitter lesson we should have learned from Vietnam. In the early days of that conflict, it might have been possible to pull out. My most vivid memories are the meetings early in Lyndon Johnson’s presidency in which his advisers (virtually all holdovers from the Kennedy administration) were looking to him for guidance on how to proceed. He, on the other hand, felt an obligation to continue the Kennedy policies and he was looking to them for indications of what steps would carry out such a course. I will always believe that someone misread a signal from the other side with the resultant commitment to full-scale fighting. After that, all the resources of the federal government were devoted to advising the president on how to do what it was thought he wanted to do.

Reedy on the White House as Versailles:

Sir Thomas Malory seems to have missed the true significance of King Arthur’s Round Table. As long as his knights ate at it every day under King Arthur’s watchful eye and lived in his palace where he could call them by shouting through the corridors, they were his to ensure that the kingdom would be ruled the way he wanted it ruled. Louis XIV did not build the Palace of Versailles as a tourist attraction but as a huge dormitory where he could keep tabs on the nobles who were disposed to become insubordinate if they spent all their time on their own estates. Peter the Great downgraded the boyars whose power rested on their distance from Moscow and brought the reins of government into his own hands by making all the top officials dependent on him. And the Turkish sultans reached the ultimate in the creation of personal force by raising young Christian boys captured in combat as Janissaries who lived solely to defend the ruler.

Reedy has a great chapter titled “What Does The President Do?”:

A president is many things. Basically, however, his functions fall into two categories. First, and perhaps most important, he is the symbol of the legitimacy and the continuity of our government. It is only through him that power can be exercised effectively-but only until opposition forces rally themselves to counter it. Second, he is the political leader of our nation. He must resolve the policy questions that will not yield to quantitative, empirical analysis and then persuade enough of his countrymen of the rightness of his decisions so that they are carried out without disrupting the fabric of society.

At the present time, neither of these functions can be carried out without the president.

He notes that the idea of the President “working” is confusing:

Despite the widespread belief to the contrary, there is far less to the presidency, in terms of essential activity, than meets the eye. The psychological burdens are heavy, even crushing, but no president ever died of overwork and it is doubtful that any ever will. The chief executive can, of course, fill his working hours with as much motion as he desires. The “crisis” days (the American hostages held in Iran or the attempted torpedoing of American navy vessels in the Gulf of Tonkin) keep office lights burning into the midnight hours. But in terms of actual administration, the presidency is pretty much what the president wants to make of it. He can delegate the “work” to subordinates and reserve for himself only the powers of decision as did Eisenhower, or he can insist on maintaining tight control over every minor detail, like Lyndon Johnson.

Presidents on vacation:

It is impossible to take a day and divide it with any sure sense of confidence into “working hours” and “nonworking hours.” But it is apparent from the large volume of words that have been written about presidents that in the past few decades, the only one who seemed able to relax completely was Eisenhower. He was capable of taking a vacation for the sake of enjoying himself, and he disdained any suggestion that he was acting otherwise.

Franklin Roosevelt apparently had little or no time to devote to relaxation. He was notorious for using his dinner hours as a means of lobbying bills through Congress. Once Harry Truman had made a decision he was able to put it out of his mind and proceed to another problem. Furthermore, he too disdained any pretensions of working when he wasn’t. But those who were close to him made it clear that he really didn’t know what to do with himself when he took a holiday. His favorite resort was Key West, Florida, where he would “go fishing” but he would hold a rod only if someone put it in his hands, and about all he really enjoyed was the sunshine and the opportunity to take long walks.

John Kennedy was described as a “compulsive reader” who could not pass up any written document regardless of its relevance to his problems or its contents. Many of his intimates reported that any spare time would find him restlessly prowling the White House looking for something to read. Lyndon Johnson anticipated with horror long weekends in which there was nothing to do. He usually spent Saturday afternoons in lengthy conferences with newspaper reporters who were hastily summoned from their homes to spend hours listening to Johnson expound the thesis that his days were so taken up with the nation’s business that he had no time to devote to friends.

The real misery of the average presidential day is the haunting knowledge that decisions have been made on incomplete information and inadequate counsel. Tragically, the information must always be incomplete and the counsel always inadequate, for in the arena of human activity in which a president operates there are no quantitative answers. He must deal with those problems for which the computer offers no solution, those disputes where rights and wrongs are so inextricably mixed that the righting of every wrong creates a new wrong, those divisions which arise out of differences in human desires rather than differences in the available facts, those crisis moments in which action is imperative and cannot wait upon orderly consideration. He has no guideposts other than his own philosophy and intuition, and if he is devoid of either, no one can substitute.

Reedy summarizes something Robert Caro goes into some detail about (how did an obscure Texas congressman obtain power?):

The office is at such a lonely eminence that no standard rules of the political game govern the approaches to it. Johnson told fascinating stories about the tactics he had used, while still a member of the House, to extract favors from FDR. He made a practice of driving Roosevelt’s secretary, Grace Tully, to the White House every morning. This gave him an opportunity to drop words in her ear, give her memoranda knowing she would pass them on to the “boss,” and learn personal characteristics that he could exploit at a later date. He once filed away in his memory the knowledge that Roosevelt was passionately interested in the techniques of dam construction. A few months later, he wangled his way into the White House with a series of huge photographs of dams that had been supplied to him by an architectural firm in his home district. Roosevelt became so absorbed in comparing the pictures that he absentmindedly okayed a rural electrification project that Johnson wanted but that had been held up by the Rural Electrification Administration for a couple of years.

None of this makes me very sanguine about either Presidential candidate, but over here at Helytimes we consider it better to look truth in the face, best we can, no?

Martin Anderson, a Reagan aide, endorsed the book in a Miller Center interview:

There’s a wonderful book called The Twilight of the Presidency by Reedy. You ever read that?

Young

George Reedy.

Anderson

In which he says, If you try to understand the White House—most people make the mistake, they try to understand the White House like a corporation or the military and how does it look, with the hierarchy. He said, The only way to understand it, it’s like a palace court. And if you can understand a palace court, then you understand the White House. I think that’s probably pretty accurate. But those are the things that happen. So anyway, I didn’t go back. So I missed Watergate.

Asher

Darn.

August 17, 2024

Paul’s Case by Willa Cather

New York has certainly inspired its share of coming-to-the-city adventures. One of the most striking is a short story by Willa Cather called “Paul’s Case,” which first appeared in The Troll Garden in 1905. Paul, a high school student in Pittsburgh, is gawky and awkward, with a “certain hysterical brilliancy” in his eyes. A fantasist and a dreamer, he is hopelessly out of sync with the life around him—but he has neither the graces nor the gifts that might enable him to escape from the constricting middle class life on suburban Cordelia Street, where he lives with his father, a widower, and there is nothing but “the loathing of respectable beds, of common food, of a home permeated by kitchen odours.” Paul comes alive only in the evenings, when he works as an usher at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Hall, wears a uniform that makes him feel handsome, guides elegant people to their seats, and listens to the music and experiences a “zest for life.” Paul is not exactly a music lover; it’s the enveloping glamour of the theater that holds him. He loves to visit backstage with the artists; “the stage entrance of the theater was for Paul the actual portal of Romance.”

But Paul’s father, a dim figure constantly urging on his son the example of more enterprising young men, becomes increasingly enraged by his son’s behavior. He pulls him out of the school he barely seems to be attending, forbids the theater to employ him or to let him through the door, and puts him to work at the offices of Denny & Carson. And suddenly Cather jumps forward, to Paul sitting on a train. He has stolen a thousand dollars in cash that he was supposed to deposit in the bank for his employer, and he is on his way to New York.

Arriving in the city, Paul buys expensive clothes, fine luggage, “silver mounted brushes and a scarf-pin” at Tiffany’s. He takes a luxurious suite at the Waldorf, and for a few days he exults in his sitting room, which he fills with flowers, in the perfectly appointed bathroom, in the elegance of the hotel dining room, in carriage rides up Fifth Avenue. He knows that it will only be a matter of days before his crime is discovered and he is tracked down. All over New York, the snow is falling. Paul’s “chief greediness,” Cather writes, “lay in his ears and eyes, and his excesses were not offensive ones. His dearest pleasures were the gray winter twilights in his sitting-room; his quiet enjoyment of his flowers, his clothes, his wide divan, his cigarette and his sense of power.” As soon as he “entered the dining-room and caught the measure of the music,” he was “lightened by his old elastic power of claiming the moment, mounting with it, and finding it all sufficient.” He exults in “the glare and glitter about him.” He is cosseted in a magical world. And when he is down to his last hundred dollars, he knows the game is up. He leaves New York, lies down on a train track in New Jersey, and lets the end come.

In Cather’s story, New York is less a place that a person can actually inhabit than a kind of luxurious illusionist’s trick, centering on the Waldorf and the city avenues, and united by the snow that softens the views out the windows and carpets everything. In “Paul’s Case” New York is not a living city so much as it is a fantasy, a stage set.

from this great 2001 essay, “The Adolescent City,” by Jed Perl.

The pages in Balzac’s Lost Illusions in which the young writer Lucien Chardon comes to Paris and wanders through the overwhelming elegance of the city constitute one of the greatest descriptions in all of literature of the tidal pull of urban life, with its intoxicating strangeness. Visual artists have generally shied away from such a theme, which necessitates unfolding, multiplying revelations, though there are a few exceptions, the greatest of which is probably Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s vast City of Good Government, painted on a wall in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena in 1338-1339. Here relations between the city and the country center around the gate of Siena, where elegant aristocrats going out for a day of hunting pass country yokels coming into town with their livestock.

source

source

August 13, 2024

Photo shoot

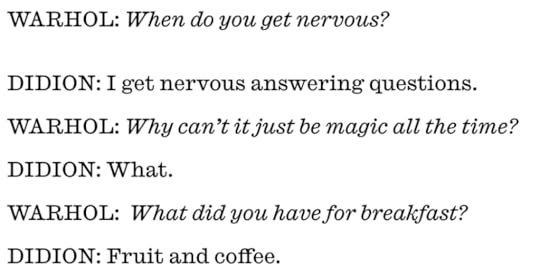

The Didion Breakfast

source. sometimes I consume the fruit and coffee breakfast.

somewhere in an old book I read a lengthy 19th century style description of how people in the tropics need to have a languid, light breakfast of fruits and sweets for their constitutions to function properly in the climate. Do places have appropriate breakfasts?

Coach Nick Saban having two Little Debbie oatmeal cream pies for breakfast every morning (“what you do every day matters”), that’s another breakfast that sticks in the mind.

August 10, 2024

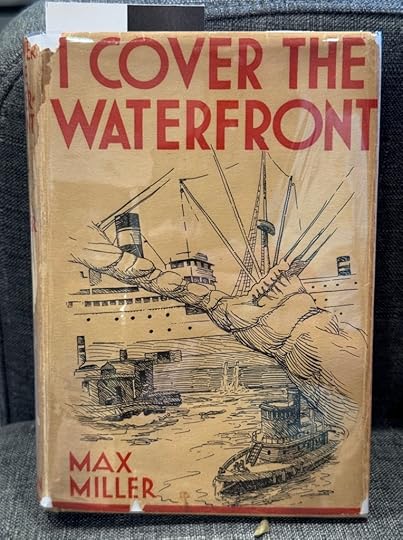

I Cover The Waterfront

Here’s the opening:

Chapter One: The Damned and the Lost

I have been here so long that even the sea gulls must recognize me. They must pass the word along about me from generation to generation, from egg to egg.

Former friends of mine, members of my old university class, acquaintances my own age, have gone out to earn their 6000 a year. They have become managers, they have become editors, they have become artists. Yet here am I, what I was six years ago, a waterfront reporter.

True, I am called a good waterfront reporter in this city, as if the humiliation were not already great enough in itself. I shudder at the compliment, yet should feel fortunate in a way that so far I have escaped the word veteran. When I am called not only the best waterfront reporter but also the veteran waterfront reporter, then for sure all hope is dissolved. And I need look ahead then, only to that day when the company presents me with a fountain pen and a final check.

I am nearing 28, and should I by accident be invited to a home where literature is discussed, or styles, or Europe, the best I could do would be tocrawl into the backyard. There I could sit tossing pebbles into the fountain until the hostess found me out. If she compelled me to come back into the house and join the conversation, my topics would have to be of swordfishing, or of lobstering, or of hunting sardines in the dark of the moon, or of fleet gunnery practice, or of cotton shipments. The predicament has passed beyond my control. I am one of those creatures who remain permanent, who stay in one place, that successful men on returning home may see for the happiness of comparison. I am of the damned and the lost, and yet I do know more than I did six years ago when I first came here, a graduate in liberal arts.

Six thousand a year. That was 1932, using the BLS inflation calculator that’s $131,821.68 today. Further investigation into the existential mystery of San Diego led me to this one.

Max Miller was waterfront reporter for San Diego’s third best newspaper in the 1930s. He worked out of a studio above the tugboat office. He remembers meeting the passengers from the big ocean liners:

He remembers Charles Lindbergh, before he was famous:

He remembers breaking some tough news:

How that one ends:

I Cover The Waterfront became a song, and a movie apparently not really based on the book.

[Miller] lived most of his life at 5930 Camino de la Costa in La Jolla, just south of Windansea (from his hillside home, he could hear the Point Loma lighthouse foghorn).

Zillow estimates that house would now cost around $16 million.

The San Diego Reader (oxymoron?)has the gossip on Miller:

But Morgan has a different interpretation. “I Cover the Waterfront was widely said among publishers to have been rewritten by a very beautiful literary agent in New York who was in love with Max at the time,” says Morgan. “It was a nasty allegation, but it was a better book than any he wrote subsequently. I tend to believe the rumor of the publishing trade.”

It’s possible. It’s also possible he was traumatized by World War Two. His title for his book about La Jolla, The Town With The Funny Name, doesn’t seem particularly inspired (is it really that funny a name? Right here in California we have Needles, Weedpatch, etc.) Or maybe he just had one good one in him.

August 8, 2024

they work well until they catastrophically come off the rails

KEN GRIFFIN: “I don’t know what that moment will be, when there is an auction that goes awry, or when the markets become dislocated. Financial markets, generally speaking, work very well until they catastrophically come off the rails. You don’t necessarily get a lot of warning that there’s about to be a big event. The crash of ’87 is a great case study. That day, I woke up, I was in my dorm room trading then, and the stories of the day were about a small skirmish in the Middle East, of frankly no consequence, and the health of First Lady Nancy Reagan. And yet, we ended that day with the stock market down twenty-some percent, and a number of American financial institutions literally on life support or near death. It happened in one day. One day. There was no big story that morning that would make you think that that day might of been the end of the U.S. capital markets as we knew them. There was no warning. And so I worry that the debt crisis may have a similar construct. That there’ll simply be a day where a major auction fails, and then you see a panic start to brew in the Treasury market. And the question will be, how fast will the Fed intervene? What panic will that induce? Because government intervention under duress often creates more panic. And then do we see a flood of treasuries coming back into the market from holders around the world?

Bloomberg Live (YouTube) – May 14, 2024. That’s from Santangel’s Value Links.

Reminded of McMurtry on stampedes and crowd behavior.

Lyn Alden had this:

In the United States, there has been quite a big gap between haves and have-nots with this fiscal and monetary mix. Those who don’t have much assets, like mainly a house, have been largely locked out of owning assets. Meanwhile, those who have assets and who have locked in those low rates, are generally in great shape, save for the fact that many of them are now kind of “stuck” in their existing home. And since the top 50% of consumers spend a lot more than the bottom 50% of consumers, the fact that the top half is doing pretty well has been a strong engine for overall consumption.

strong engine for overall consumption.