Steve Hely's Blog, page 8

February 7, 2025

Spoonful

Have been listening to Spoonful as recorded by Howlin Wolf lately.

The lyrics relate men’s sometimes violent search to satisfy their cravings, with “a spoonful” used mostly as a metaphor for pleasures, which have been interpreted as sex, love, and drugs

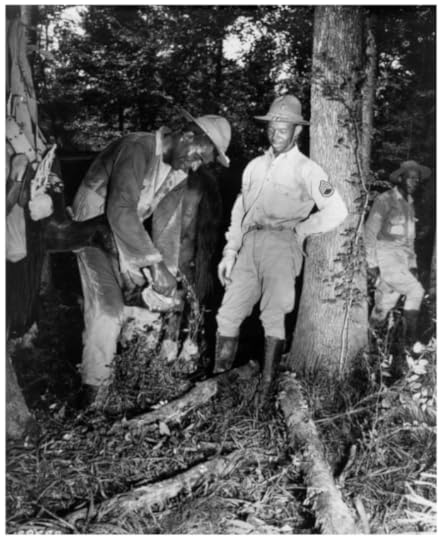

Chester Arthur Burnett was born in White Station Mississippi, near West Point, in the “Black Prairie” (later remarketed as the “Golden Triangle“). JD Walsh digs up a photo, source undescribed, of our guy working on a horse’s hoof while he was in the 9th Cavalry.

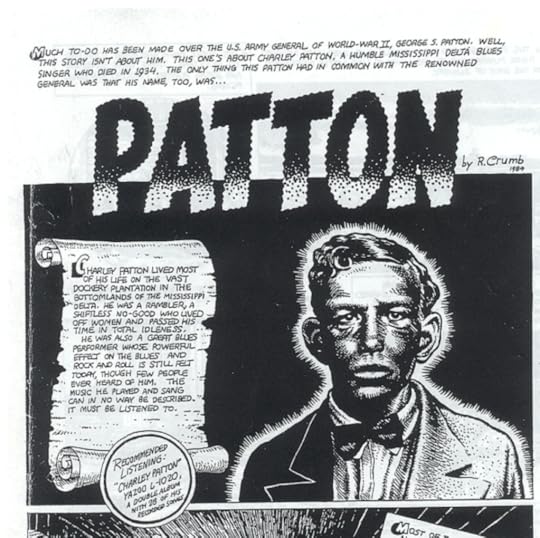

Howlin Wolf was an apprentice/student to Charlie Patton. I first heard about Charlie Patton from R. Crumb’s comic, which was reprinted in an anthology of underground comics they had at the Needham Public Library.

The Library also had a cassette of some of these blues guys. Living walking distance to the library, a life-changer.

Blues research is a famous graveyard for the curious – we’ve gone about as far as we dare on this topic, see previous coverage. Listening to Charlie Patton especially with the warble of the old recordings sounds spooky, and there’s a desire to see this as emerging from some mysterious beyond, but the turth might be more interesting, these people were modern. Elijah Wald shed some light on Delta blues in his book Escaping the Delta:

If someone had suggested to the major blues stars that they were old-fashioned folk musicians carrying on a culture handed down from slavery times, most would probably have been insulted.

Mississippi was legally dry until 1966, at least in theory, a factor in blues history.

It is startling to thank that all of the evolution from the first Bessie Smith record to the first Rolling Stones record took only forty years. When Skip James and John Hurt appeared at the Newport Folk Festival, they were greeted as emissaries from an ancient, vanished world, but it was only three decades since they had first entered a recording studio – that is, they were about as ancient as disco is to us today.

The Mississippi Delta at this time was actually kind of a dynamic region, crisscrossed with railroads, you could quit your job and move and get another one.

Wald tells of an anthropological team from Fisk University and the Library of Congress that visited the Delta in 1941 and 1942. They reported:

There are no memories of slavery in the delta. This section of the delta has little history prior to the revolution of 1861

Howlin’ Wolf was on to health insurance for musicians long before Chappell Roan was born:

After he married Lillie, who was able to manage his professional finances, he was so financially successful that he was able to offer band members not only a decent salary but benefits such as health insurance. This enabled him to hire his pick of available musicians and keep his band one of the best around. According to his stepdaughters, he was never financially extravagant (for instance, he drove a Pontiac station wagon rather than a more expensive, flashy car).[48]

That Sun Records link reports that Howlin’ Wolf was 6’6″ and close to 300 lbs.

February 3, 2025

reviewing some news in The Wall Street Journal

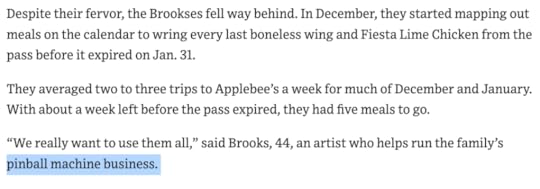

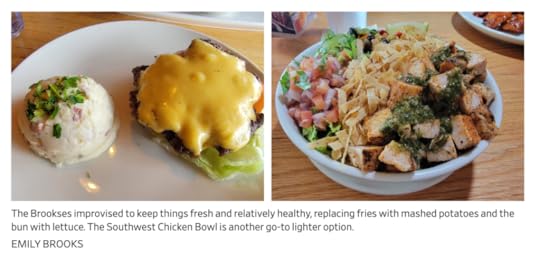

I don’t care for Applebee’s, it’s sub Friday’s and way sub Chili’s, but I do like living in the United States of America. All told this was a nice story. The conclusion:

January 31, 2025

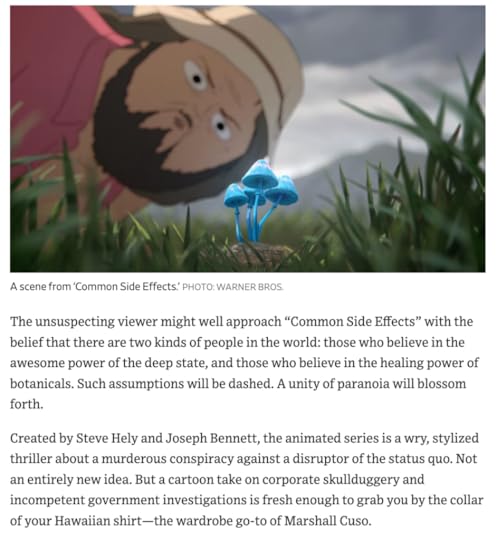

Common Side Effects, Sunday Feb 2 11:30pm on Cartoon Network, streaming on MAX Feb 3

Our attitude towards critics is influenced by the Duke of Wellington, who supposedly didn’t let his troops cheer for him because that meant they could also boo him.

While he is said to have disapproved of soldiers cheering as “too nearly an expression of opinion”,[247] Wellington nevertheless cared for his men

(He did call them the scum of the earth but w/e).

But hey, these reviews are terrific and we must celebrate our wins in a business full of heartbreak. Making a TV show is so difficult and time consuming, Resistance fights the work of art at every stage, very blessed to have worked with this amazing team on this project.

Here is The New York Times. And we’ll take this one:

A treat and a half says Margaret Lyons!

Here’s a funny one, a pharma ad embedded right in there:

(I don’t think the reporter here edited his AI transcript.) Neil Postman would’ve predicted if you made a TV show satirizing pharmaceuticals they would use it to sell pharmaceuticals. In Amusing Ourselves to Death he predicted The Daily Show.

Anyhoo watch, stream, and spread the word, we’ll return to amateur history and digestions here on Helytimes as time permits! I’ve been meeting to write up the Atlanta Cyclorama, where Van Gogh bought his paints and the role of the aluminum tube in art history, Lester Hiatt’s Arguments About Aborigines, Dan Levy’s Maxims For Thinking Analytically, Randall Collins Violence, the Santa Barbara Channel, and more!

The Chumash people of the region have traditionally known Point Conception as the “Western Gate”, through which the souls of the dead could pass between the mortal world and the heavenly paradise of Similaqsa.[4]

It is called Humqaq (“The Raven Comes”) in the Chumashan languages.

January 30, 2025

Carter’s, congealed electricity, AI and Needham

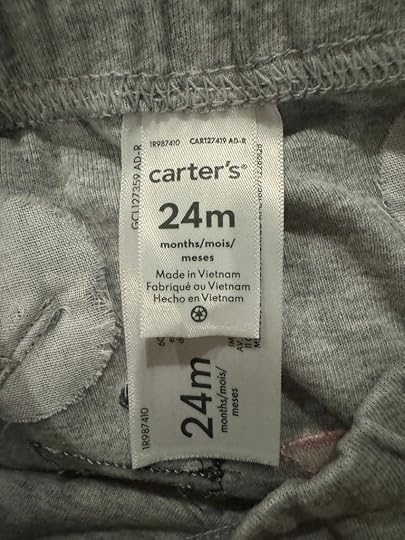

If you have a little kid in the US you will have some clothes from Carter’s. They sell them at Target and Wal-Mart as well as 1,000 or so Carter’s stores, and they cost $8.

Before I had a kid it didn’t occur to me that kids outgrow their clothes so fast they can’t cost too much.

When I see the Carter’s label, I think of my home town.

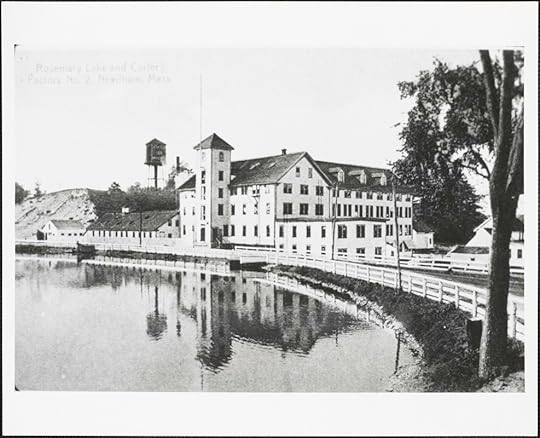

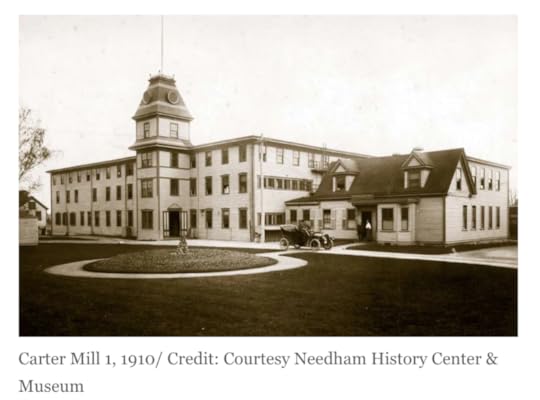

William Carter founded Carter’s in Needham, Massachusetts in 1865. Textiles were a big business in New England. Two inputs, labor and electricity, were cheap. Labor from excess farm children, and electricity from running streams? That would’ve been the earliest mode, what were they using by 1865? Coal?

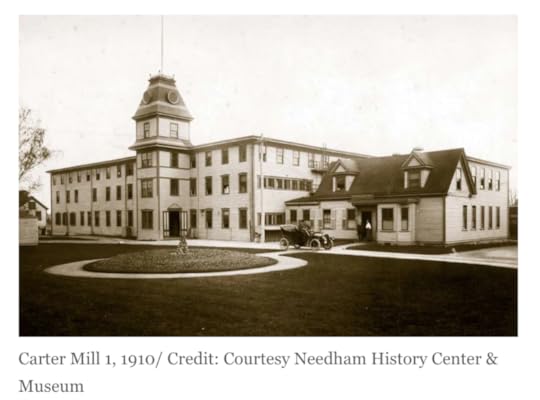

One of the biggest buildings in Needham, certainly the longest, is the former Carter’s headquarters, which stretches itself along Highland Avenue. A prominent landmark, it took a long time to walk past.

The story of Carter’s is a global economic story in miniature.

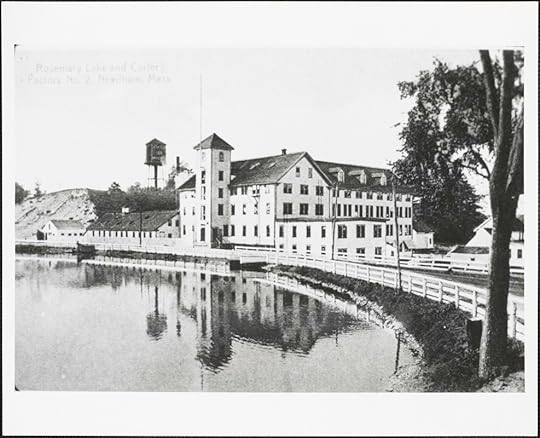

Old Carter mill #2, found here.

The Carter family sold the company in the 1990s. It went public in 2003. In 2005, Carter’s acquired OshKosh B’gosh, a company famous for making children’s overalls. This company started in 1895 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin (the name comes from an Ojibwe word, “The Claw,” that was the name of a local chief).

The term “B’gosh” began being used in 1911, after general manager William Pollock heard the tagline “Oshkosh B’Gosh” in a vaudeville routine in New York.[4] The company formally adopted the name OshKosh B’gosh in 1937.

OshKosh B’Gosh’s Wisconsin plant was closed in 1997. Downsizing of domestic operations and massive outsourcing and manufacturing at Mexican and Honduran subsidiaries saw the domestic manufacturing share drop below 10 percent by the year 2000.

OshKosh B’Gosh was sold to Carter’s, another clothing manufacturer for $312 million

The headquarters of Carter’s moved to Atlanta. Labor and electricity were cheaper in Georgia, Carter’s had been opening mills in the South for awhile. Now the clothes are made overseas. I look at the labels on Carter’s clothes: Bangladesh, India, Cambodia, Vietnam. If you factor in the shipping and the markup how much of that $8 is going to your garment maker in Bangladesh? Then again maybe it’s the best job around, raising Bangladeshis out of poverty, and soon Chittagong will look like Needham.

The former Carter’s headquarters, now vacant, became a facility for elder living. My mom worked there, briefly. Carter’s today is headquarted in the Phipps Tower in Buckhead, Atlanta, which I happened to pass by the other day.

The loss of the mill and the company headquarters was not a crisis for Needham. Needham is very close to Boston, an easy train ride away, and along of the 128 Corridor. There are growth businesses in the area, hospitals, biotech companies, universities. TripAdvisor is based in Needham. Needham is a pleasant town, there are ongoing talks to turn the former Carter’s building into housing. It would be close to public transport and walkable to the library and the Trader Joe’s. That seems to be stalled.

Needham has brain jobs, attached to a dense brain network, while brawn jobs are being shipped overseas. There are many other towns in Massachusetts where the old run down mill is a sad derelict as production moved first south and then overseas. These towns are bleak. Oshkosh, Wisconsin seems ok, but the shipping of steady jobs overseas is of course a major factor in our politics, Ross Perot was talking about it in 1992 and no one did anything about it and now Trump is the president.

A similar story lies in the history of Berkshire Hathaway – the original New Bedford textile mill, not the conglomerate Warren Buffett built on top of it using the same name. Buffett talks about this, I believe this is from the 2022 annual meeting:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I remember when you had a textile mill —

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, god.

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and it couldn’t —

WARREN BUFFETT: I try to forget it. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and the textiles are really just congealed electricity, the way modern technology works.

And the TVA rates were 60% lower than the rates in New England. It was an absolutely hopeless hand, and you had the sense to fold it.

WARREN BUFFETT: Twenty-five years later, yeah. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, you didn’t pour more money into it.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, that’s right.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And, no — recognizing reality, when it’s really awful, and taking appropriate action, just involves, often, just the most elementary good sense.

How in the hell can you run a textile mill in New England when your competitors are paying way lower power rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: And I’ll tell you another problem with it, too. I mean, the fellow that I put in to run it was a really good guy. I mean, he was 100% honest with me in every way. And he was a decent human being, and he knew textiles.

And if he’d been a jerk, it would have been a lot easier. I would have probably thought differently about it.

But we just stumbled along for a while. And then, you know, we got lucky that Jack Ringwalt decided to sell his insurance company [National Indemnity] and we did this and that.

But I even bought a second textile company in New Hampshire, I mean, I don’t know how many — seven or eight years later.

I’m going to talk some about dumb decisions, maybe after lunch we’ll do it a little.

Congealed electricity, what a phrase. In the 1985 annual letter, Buffett discusses the other input, labor, which was cheaper in the South, and why he kept Berkshire Hathaway running in Massachusetts anyway:

At the time we made our purchase, southern textile plants – largely non-union – were believed to have an important competitive advantage. Most northern textile operations had closed and many people thought we would liquidate our business as well.

We felt, however, that the business would be run much betterby a long-time employee whom. we immediately selected to be president, Ken Chace. In this respect we were 100% correct: Ken

and his recent successor, Garry Morrison, have been excellent managers, every bit the equal of managers at our more profitable businesses.

… the domestic textile industry operates in a commodity business, competing in a world market in which substantial excess capacity exists. Much of the trouble we experienced was attributable, both directly and indirectly, to competition from foreign countries whose workers are paid a small fraction of the U.S. minimum wage. But that in no way means that our labor force deserves any blame for our closing. In fact, in comparison with employees of American industry generally, our workers were poorly paid, as has been the case throughout the textile business. In contract negotiations, union leaders and members were sensitive to our disadvantageous cost position and did not push for unrealistic wage increases or unproductive work practices. To the contrary, they tried just as hard as we did to keep us competitive. Even during our liquidation period they performed superbly. (Ironically, we would have been better off financially if our union had behaved unreasonably some years ago; we then would have recognized the impossible future that we faced, promptly closed down, and avoided significant future losses.)

Buffett goes on, if you care to read it, to discuss the dismal spiral faced by another New England textile company, Burlington.

Charlie Munger, in his 1994 USC talk, spoke on the paradoxes here:

For example, when we were in the textile business, which is a terrible commodity business, we were making low-end textiles—which are a real commodity product. And one day, the people came to Warren and said, ‘They’ve invented a new loom that we think will do twice as much work as our old ones.’

And Warren said, ‘Gee, I hope this doesn’t work because if it does, I’m going to close the mill.’ And he meant it.

What was he thinking? He was thinking, ‘It’s a lousy business. We’re earning substandard returns and keeping it open just to be nice to the elderly workers. But we’re not going to put huge amounts of new capital into a lousy business.’

And he knew that the huge productivity increases that would come from a better machine introduced into the production of a commodity product would all go to the benefit of the buyers of the textiles. Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.

That’s such an obvious concept—that there are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Is something similar happening with AI? Who will it make rich, and at what cost? To whose ribs will the profits stick?

I’m not sure we could call AI congealed but it is more or less just more and more electricity run through expensive processors. Who will win from that? So far it’s been the makers of the processors, but if DeepSeek shows you don’t need as many of those the game is changed. Personally I’m unimpressed with DeepSeek – try asking it what happened in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

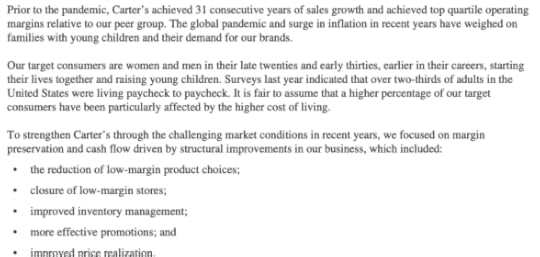

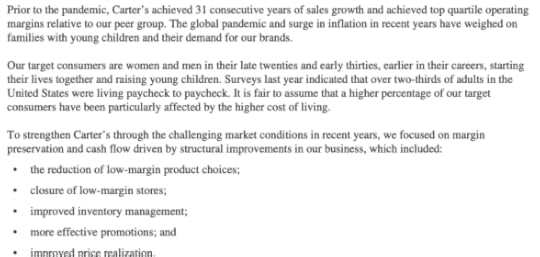

How does Carter’s itself continue to survive? Target’s own brand, Cat & Jack, is right next door on the shelves. Could another company shove Carter’s aside if they can cut the margins even thinner, get the price down to $7? Here’s what Carter’s CEO Michael Casey has to say in their most recent annual letter:

Hard to build the operational network Carter’s has over 150+ years. There will be a challenge awaiting the next CEO of Carter’s as Michael Casey is retiring. Carter’s stock ($CRI) is pretty beaten up over the past year, down 30%. A possible macro problem for Carter’s is that the number of births in the United States appears to be declining.

It is powerful, when I’m changing my daughter, to contemplate my home town, and global commerce, and the people in Cambodia who made these clothes, and the ways of the world.

Carter’s, congealed electricity and Needham

If you have a little kid in the US you will have some clothes from Carter’s. They sell them at Target and Wal-Mart as well as 1,000 or so Carter’s stores, and they cost $8.

Before I had a kid it didn’t occur to me that kids outgrow their clothes so fast they can’t cost too much.

When I see the Carter’s label, I think of my home town.

William Carter founded Carter’s in Needham, Massachusetts in 1865. Textiles were a big business in New England. Two inputs, labor and electricity, were cheap. Labor from excess farm children, and electricity from running streams? That would’ve been the earliest mode, what were they using by 1865? Coal?

One of the biggest buildings in Needham, certainly the longest, is the former Carter’s headquarters, which stretches itself along Highland Avenue. A prominent landmark, it took a long time to walk past.

The story of Carter’s is a global economic story in miniature.

Old Carter mill #2, found here.

The Carter family sold the company in the 1990s. It went public in 2003. In 2005, Carter’s acquired OshKosh B’gosh, a company famous for making children’s overalls. This company started in 1895 in Oshkosh, Wisconsin (the name comes from an Ojibwe word, “The Claw,” that was the name of a local chief).

The term “B’gosh” began being used in 1911, after general manager William Pollock heard the tagline “Oshkosh B’Gosh” in a vaudeville routine in New York.[4] The company formally adopted the name OshKosh B’gosh in 1937.

OshKosh B’Gosh’s Wisconsin plant was closed in 1997. Downsizing of domestic operations and massive outsourcing and manufacturing at Mexican and Honduran subsidiaries saw the domestic manufacturing share drop below 10 percent by the year 2000.

OshKosh B’Gosh was sold to Carter’s, another clothing manufacturer for $312 million

The headquarters of Carter’s moved to Atlanta. Labor and electricity were cheaper in Georgia, Carter’s had been opening mills in the South for awhile. Now the clothes are made overseas. I look at the labels on Carter’s clothes: Bangladesh, India, Cambodia, Vietnam. If you factor in the shipping and the markup how much of that $8 is going to your garment maker in Bangladesh? Then again maybe it’s the best job around, raising Bangladeshis out of poverty, and soon Chittagong will look like Needham.

The former Carter’s headquarters, now vacant, became a facility for elder living. My mom worked there, briefly. Carter’s today is headquarted in the Phipps Tower in Buckhead, Atlanta, which I happened to pass by the other day.

The loss of the mill and the company headquarters was not a crisis for Needham. Needham is very close to Boston, an easy train ride away, and along of the 128 Corridor. There are growth businesses in the area, hospitals, biotech companies, universities. TripAdvisor is based in Needham. Needham is a pleasant town, there are ongoing talks to turn the former Carter’s building into housing. It would be close to public transport and walkable to the library and the Trader Joe’s. That seems to be stalled.

Needham has brain jobs, attached to a dense brain network, while brawn jobs are being shipped overseas. There are many other towns in Massachusetts where the old run down mill is a sad derelict as production moved first south and then overseas. These towns are bleak. Oshkosh, Wisconsin seems ok, but the shipping of steady jobs overseas is of course a major factor in our politics, Ross Perot was talking about it in 1992 and no one did anything about it and now Trump is the president.

A similar story lies in the history of Berkshire Hathaway – the original New Bedford textile mill, not the conglomerate Warren Buffett built on top of it using the same name. Buffett talks about this, I believe this is from the 2022 annual meeting:

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, I remember when you had a textile mill —

WARREN BUFFETT: Oh, god.

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and it couldn’t —

WARREN BUFFETT: I try to forget it. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: — and the textiles are really just congealed electricity, the way modern technology works.

And the TVA rates were 60% lower than the rates in New England. It was an absolutely hopeless hand, and you had the sense to fold it.

WARREN BUFFETT: Twenty-five years later, yeah. (Laughs)

CHARLIE MUNGER: Well, you didn’t pour more money into it.

WARREN BUFFETT: No, that’s right.

CHARLIE MUNGER: And, no — recognizing reality, when it’s really awful, and taking appropriate action, just involves, often, just the most elementary good sense.

How in the hell can you run a textile mill in New England when your competitors are paying way lower power rates?

WARREN BUFFETT: And I’ll tell you another problem with it, too. I mean, the fellow that I put in to run it was a really good guy. I mean, he was 100% honest with me in every way. And he was a decent human being, and he knew textiles.

And if he’d been a jerk, it would have been a lot easier. I would have probably thought differently about it.

But we just stumbled along for a while. And then, you know, we got lucky that Jack Ringwalt decided to sell his insurance company [National Indemnity] and we did this and that.

But I even bought a second textile company in New Hampshire, I mean, I don’t know how many — seven or eight years later.

I’m going to talk some about dumb decisions, maybe after lunch we’ll do it a little.

Congealed electricity, what a phrase. In the 1985 annual letter, Buffett discusses the other input, labor, which was cheaper in the South, and why he kept Berkshire Hathaway running in Massachusetts anyway:

At the time we made our purchase, southern textile plants – largely non-union – were believed to have an important competitive advantage. Most northern textile operations had closed and many people thought we would liquidate our business as well.

We felt, however, that the business would be run much betterby a long-time employee whom. we immediately selected to be president, Ken Chace. In this respect we were 100% correct: Ken

and his recent successor, Garry Morrison, have been excellent managers, every bit the equal of managers at our more profitable businesses.

… the domestic textile industry operates in a commodity business, competing in a world market in which substantial excess capacity exists. Much of the trouble we experienced was attributable, both directly and indirectly, to competition from foreign countries whose workers are paid a small fraction of the U.S. minimum wage. But that in no way means that our labor force deserves any blame for our closing. In fact, in comparison with employees of American industry generally, our workers were poorly paid, as has been the case throughout the textile business. In contract negotiations, union leaders and members were sensitive to our disadvantageous cost position and did not push for unrealistic wage increases or unproductive work practices. To the contrary, they tried just as hard as we did to keep us competitive. Even during our liquidation period they performed superbly. (Ironically, we would have been better off financially if our union had behaved unreasonably some years ago; we then would have recognized the impossible future that we faced, promptly closed down, and avoided significant future losses.)

Buffett goes on, if you care to read it, to discuss the dismal spiral faced by another New England textile company, Burlington.

Charlie Munger, in his 1994 USC talk, spoke on the paradoxes here:

For example, when we were in the textile business, which is a terrible commodity business, we were making low-end textiles—which are a real commodity product. And one day, the people came to Warren and said, ‘They’ve invented a new loom that we think will do twice as much work as our old ones.’

And Warren said, ‘Gee, I hope this doesn’t work because if it does, I’m going to close the mill.’ And he meant it.

What was he thinking? He was thinking, ‘It’s a lousy business. We’re earning substandard returns and keeping it open just to be nice to the elderly workers. But we’re not going to put huge amounts of new capital into a lousy business.’

And he knew that the huge productivity increases that would come from a better machine introduced into the production of a commodity product would all go to the benefit of the buyers of the textiles. Nothing was going to stick to our ribs as owners.

That’s such an obvious concept—that there are all kinds of wonderful new inventions that give you nothing as owners except the opportunity to spend a lot more money in a business that’s still going to be lousy. The money still won’t come to you. All of the advantages from great improvements are going to flow through to the customers.”

Is something similar happening with AI? Who will it make rich, and at what cost? To whose ribs will the profits stick?

I’m not sure we could call AI congealed but it is more or less just more and more electricity run through expensive processors. Who will win from that? So far it’s been the makers of the processors, but if DeepSeek shows you don’t need as many of those the game is changed. Personally I’m unimpressed with DeepSeek – try asking it what happened in Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

How does Carter’s itself continue to survive? Target’s own brand, Cat & Jack, is right next door on the shelves. Could another company shove Carter’s aside if they can cut the margins even thinner, get the price down to $7? Here’s what Carter’s CEO Michael Casey has to say in their most recent annual letter:

Hard to build the operational network Carter’s has over 150+ years. There will be a challenge awaiting the next CEO of Carter’s as Michael Casey is retiring. Carter’s stock ($CRI) is pretty beaten up over the past year, down 30%. A possible macro problem for Carter’s is that the number of births in the United States appears to be declining.

It is powerful, when I’m changing my daughter, to contemplate my home town, and global commerce, and the people in Cambodia who made these clothes, and the ways of the world.

January 25, 2025

Gizmodo interview

As Matt at the office put it, they came out SWINGING with Luigi as the first question:

I declare the event both “upsetting” but also “cool”? Maybe I do need media training. Here’s a link.

Here’s what matters:

Streaming next day on MAX. Is it still called HBO Max in Australia? I know they’ve got Max in Europe and LatAm.

Occurs to me this site has been lax on one of our missions, reporting news from Helys around the world. There’s just too much!

Texas Wines

(source. post title can be sung to the tune of Khuangbin and Leon Bridges, “Texas Sun”)

From my father in law I came into possession of several bottles of Texas wine.

Texas has the most native grapes of any state, we are told by Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson in their World Atlas of Wine (8th Edition), but these are not vinifera, the species of grape we’re usually talking about to make wines. You can make wines out of other grapes, but they tend to have a quality described as “foxy,” which seems to be like musty. The Concord grape’s taste is sometimes suggested as a referent.

Johnson and Robinson:

Of the 65-70 species of the genus Vitis scattered around the world, no fewer than 15 are Texas natives – a fact that was turned to important use during the phylloxera epidemic. Thomas V Munson of Denison, Texas, made hundreds of hybrids between Vitis vinifera and indigenous vines in his eventually successful search for immune rootstock. It was a Texan who saved not only France’s but the whole world’s wine industry.

they continue:

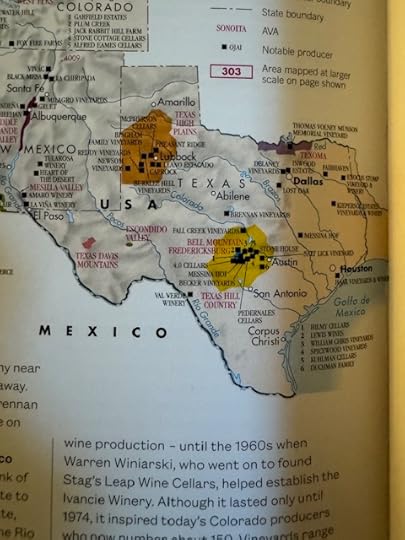

As much as 80% of all Texas wine grapes are grown in the High Plains, but about three-quarters of them are shipped to one of the 50 or so wineries in the Hill Country of Central Texas, west of Austin. The vast Texas Hill Country AVA is the second most extensive in the US, and includes both the Fredericksburg and Bell Mountain AVAs within it. The total area of these three AVAs is 9 million acres (3.6 million ha), but a mere 800 acres (324ha) are planted with vines.

Their map:

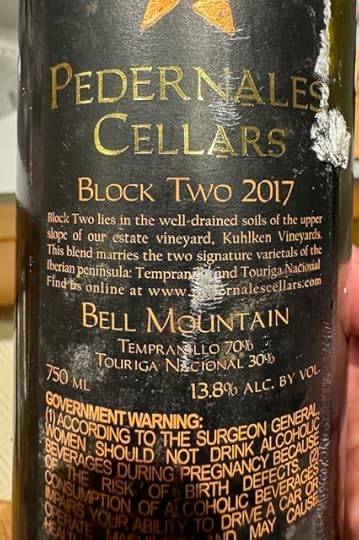

Of these wines, Pedernales Block 2 was most impressive to me. This could be a competition wine. Set it against your French and Spanish and Italian and California wines and see if it can’t hold up.

It looks like Kuhlken Vineyards is right across the river from Lyndon Johnson’s ranch. He used to drive his amphibious car in the Pedernales.

(source)

Now, if you’re looking for structure in your wines, Texas ain’t the place.

This one initially smelled of sweet barbecue sauce. Not saying that’s a bad thing, just something you should know. I would say it “opened up” most generously and I respected this wine, I felt like by the time I’d finished a glass this wine and I were pals.

The Davis Mountains AVA seems like more a hope than a real center of production for now, but someday it could be really special. Next time I’m in Marfa I will try Alta Marfa wines.

How much wine do you think you need to drink to become a professional wine critic?

Lettie Teague of the WSJ my model here. I think I drink a reasonable amount of wine, but probably not even close to the professional level.

The way in to wine for me is geography. Tastes and notes are fine to discuss at the tasting room but I want to go to the Margaret River and the base of Etna and Yountville and St. Emilion and yes, even Lubbock. The Hill Country for sure.

My mother in law was a pioneer of Texas wine writing, I wish I could discuss these wines with her. She has gone to the great AVA in the sky.

January 18, 2025

Lincoln in New Orleans (featuring final answer on was Abraham Lincoln gay?)

In the year 1828 that nineteen year old Abraham Lincoln went on a flatboat trip with a local twenty one year old named Allen Gentry. He would be paid eight dollars a month plus steamboat fare home. They left from Spencer County, Indiana, down the Ohio to the Mississippi.

The great New Orleans geographer and historian Richard Campanella wrote a whole book, Lincoln In New Orleans, about Lincoln’s experience on this trip and another down in New Orleans. It’s a really illuminating work on Lincoln, the Mississippi River at that time, the floatboatman life, early New Orleans.

If you need step by step instructions on building a flatboat, they’re in Campanella’s book. (People back then worked so hard!)

Campanella tells us in vivid reconstruction from various sources what this trip must’ve been like:

the Mississippi River in its deltaic plain no longer collected water through tributaries but shed it, through distributaries such as bayous Manchac, Plaquemine, and Lafourche (“the fork”). This was Louisiana’s legendary

“sugar coast,” home to plantation after plantation after plantation, with their manor houses fronting the river and dependencies, slave cabins, and

“long lots” of sugar cane stretching toward the backswamp. The sugar coast claimed many of the nation’s wealthiest planters, and the region had one of the highest concentrations of slaves (if not the highest) in North America. To visitors arriving from upriver, Louisiana seemed more Afro-Caribbean than American, more French than English, more Catholic than Protestant, more tropical than temperate. It certainly grew more sugar cane than cotton (or corn or tobacco or anything else, probably combined).

To an upcountry newcomer, the region felt exotic; its society came across as foreign and unknowable. The sense of mystery bred anticipation for the urban culmination that lay ahead.

What Lincoln did in New Orleans is recorded only in a few stray remarks from the man himself and secondhand stories remembered afterwards by those he told them to, who then told them to William Herndon, biographer and law partner of Lincoln. (now they can be found in a volume called Herndon’s Informants). What was Lincoln like in New Orleans?

Observing the behavior of young men today, sauntering in the French Quarter while on leave from service, ship, school, or business, offers an idea of how flatboatmen acted upon the stage of street life in the circa-1828 city. We can imagine Gentry and Lincoln, twenty and nineteen years old respectively, donning new clothes and a shoulder bag, looking about, inquiring what the other wanted to do and secretly hoping it would align with his own wishes, then shrugging and ambling on in a mutually consensual direction. Lincoln would have attracted extra attention for his striking physiognomy, his bandaged head wound from the attack on the sugar coast, and his six-foot-four height, which towered ten inches over the typical American male of that era and even higher above the many New Orleanians of Mediterranean or Latin descent.

Quite the conspicuous bumpkins were they.

One cannot help pondering how teen-aged Lincoln might have behaved in New Orleans. Young single men like him (not to mention older married men) had given this city a notorious reputation throughout the Western world; condemnations of the city’s wickedness abound in nineteenth-century literature. A visitor in 1823 wrote,

New Orleans is of course exposed to greater varieties of human misery, vice, disease, and want, than any other American town. … Much has been said about [its] profligacy of manners, morals… debauchery, and low vice … [T]his place has more than once been called the modern Sodom.

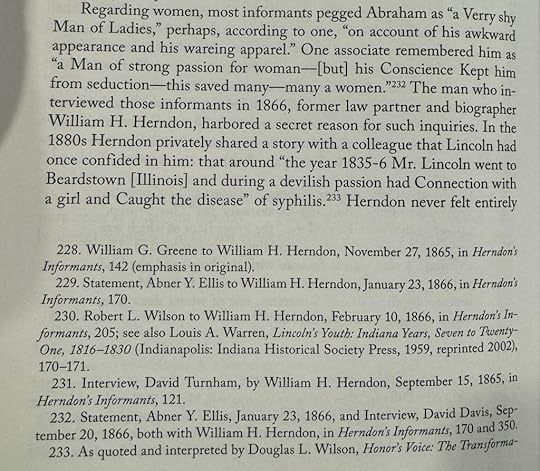

Campanella considers what we know about Lincoln and women:

I consider the matter concluded that Abe was a gentle shyguy ladykiller.

I found this passage very real:

Campanella gives us the political context of the time:

There was much to editorialize about in the spring of 1828. A concurrence of events made politics particularly polemical that season. Just weeks earlier, Denis Prieur defeated Anathole Peychaud in the New Or-leans mayoral race, while ten council seats went before voters. They competed for attention with the U.S. presidential campaign— a mudslinging rematch of the bitterly controversial 1824 election, in which Westerner Andrew Jackson won a plurality of both the popular and electoral vote in a four-candidate, one-party field, but John Quincy Adams attained the presidency after Congress handed down the final selection. Subsequent years saw the emergence of a more manageable two-party system. In 1828, Jackson headed the Democratic Party ticket while Adams represented the National Republican Party (forerunner of the Whig Party, and later the Republican Party). Jackson’s heroic defeat of the British at New Orleans in 1815 had made him a national hero with much local support, but did not spare him vociferous enemies. The year 1828 also saw the state’s first election in which presidential electors were selected by voters-white males, that is—rather than by the legislature, thus ratcheting up public interest in the contest. 238 Every day in the spring of 1828 the local press featured obsequious encomiums, sarcastic diatribes, vicious rumors, or scandalous allegations spanning multiple columns. The most infamous-the “coffin hand bills,” which accused Andrew Jackson of murdering several militiamen executed under his command during the war—-circulated throughout the city within days of Lincoln’s visit. 23% New Orleans in the red-hot political year of 1828 might well have given Abraham Lincoln his first massive daily dosage of passionate political opinion, via newspapers, broadsides, bills, orations, and overheard conversations.

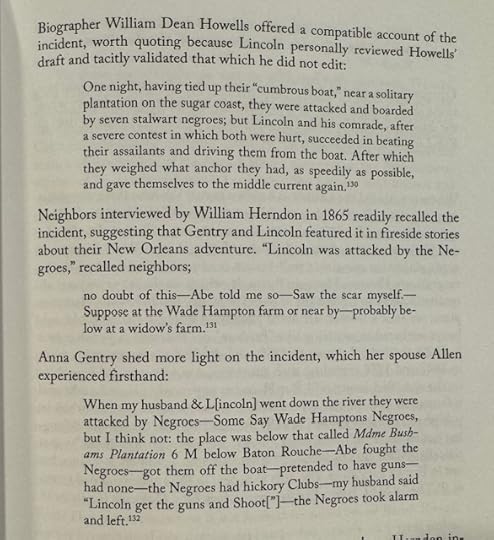

Before they got to New Orleans, Lincoln and Gentry were attacked by a group of seven Negroes, possibly runaway slaves? Little is known for sure about the incident, except that they messed with the wrong railsplitter. Lincoln was famously strong and a good fighter:

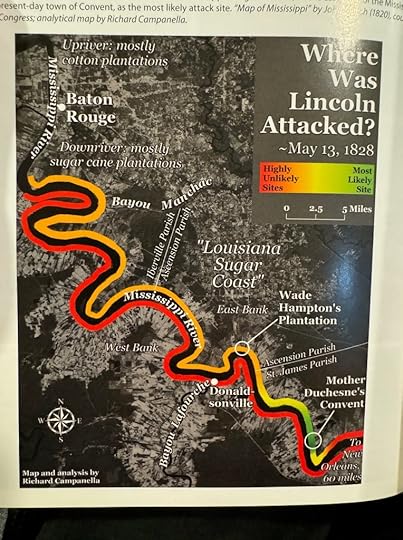

In a remarkable bit of historical detective work, Campanella concludes that a woman sometimes called “Bushan” may have been Dufresne, and puts together this incredible map:

Really impressed with Campanella’s work, I also have his book Bienville’s Dilemma, and add him to my esteemed Guides to New Orleans. Campanella goes into some detail about how and in what forms Lincoln would’ve encountered slavery on this trip. Any dramatic statement about it he made during the trip though seems historically questionable. When Lincoln talked about this trip in political speeches, he used it as an example of how he’d once been a working man. For example, 1860 in New Haven:

Free society is such that a poor man knows he can better his condition; he knows that there is no fixed condition of labor, for his whole life. I am not ashamed to confess that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat—just what might happen to any poor man’s son! I want every man to have the chance—and I believe a black man is entitled to it—in which he can better his condition-when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him!’

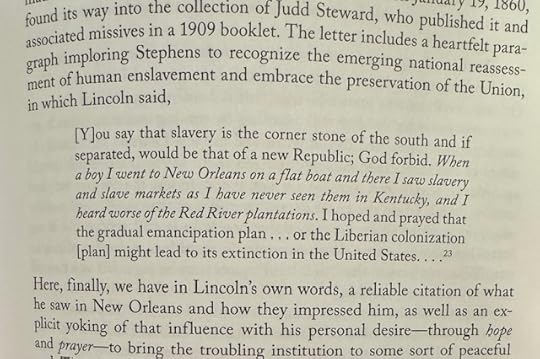

Campanella does cite a letter Lincoln wrote in 1860 where he did speak on what he saw of slavery:

Making a flatboat trip was a rite of passage for a young buck of the Midwest at that time. Whether it brought Lincoln to full maturity is discussed in a poignant and comic anecdote:

An awkward incident one year after the New Orleans trip yanked the maturing but not yet fully mature Abraham back into the petty world of past grievances. How he dealt with it reflected his growing sophistication as well as his lingering adolescence. Two Grigsby brothers— kin of Aaron, the former brother-in-law whom Abraham resented for not having done enough to aid his ailing sister Sarah Lincoln-married their fiancées on the same day and celebrated with a joint “infare.” The Grigsbys pointedly did not invite Lincoln. In a mischievous mood, Abraham exacted revenge by penning a ribald satire entitled “The Chronicles of Reuben,” in which the two grooms accidentally end up in bed together rather than with their respective brides. Other locals suffered their own indignities within the stinging verses of Abraham’s poem, nearly resulting in fisticuffs. The incident botses tected and exacerbated Lincoln’s growing rift with all things related to Spencer County.

An article version of Campanella’s book is available free.

That painting is of course Jolly Flatboatmen, which we discussed back in 2012.

January 16, 2025

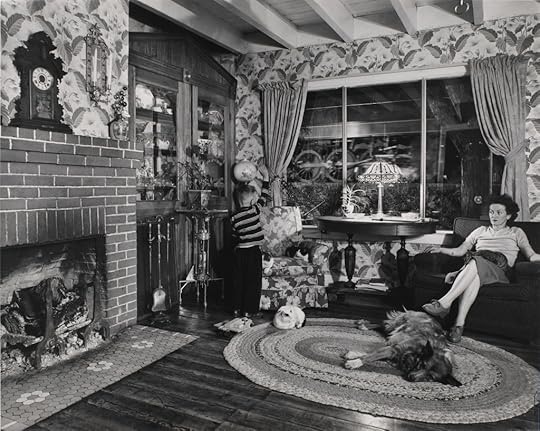

Living Room on the tracks

Direct capture

Direct captureA photo by O. Winston Link, at the Smithsonian. That is Lithia, Virginia.

January 14, 2025

Stuart Spencer (1927-2025)

I read in The LA Times that Stuart Spencer died. His Miller Center Oral History interview is one of the most vivid on the rise of Ronald Reagan, California, politics in general:

After many discussions with [Reagan], we realized this guy was a basic conservative. He was obsessed with one thing, the communist threat. He has conservative tendencies on other issues, but he can be practical.

When you look at the 1960s, that’s a pretty good position to be in, philosophically and ideologically. Plus, we realized pretty early on that the guy had a real core value system. Most people in my business don’t like to talk about that, but you know something? The best candidates have a core value system. Either party, win or lose, those are still the best candidates. They don’t lose because of their core value system. They lose because of some other activity that happens out there. But the best candidates to deal with, and to work with, are those who have that. A lot of them have it and a lot of them don’t, but Reagan had it.

The power players of Southern California:

Holmes Tuttle was a man of great . . . He was a car dealer, a Ford dealer in southern California and he also had some agencies in Tucson, I think. Holmes was a guy that came from Oklahoma on a freight car. He had no money and he started working—I don’t think he finished high school—for a car dealership, washing cars, cleaning cars. He’s a man of tremendous energy, tremendous drive and strong feelings—which most successful businessmen have—about how the world should be run, how the country should be run as well as how their business should be run and how your business should be run. They’re always tough and strong that way. That was Holmes’ background.

In the southern California—I won’t say California because we have two segments, north and south—framework of the late ’30s and the ’40s, there were movies made about a group. I can’t remember what they were called, but there were 30 of them. In this group were the owner and publisher of the L.A. Times, the [Harry] Chandler family top business guys, Asa Call of what is now known as Pacific Insurance. It was Pacific Mutual Insurance then, a local company. Now it’s a national company. Henry Salvatori, the big oil guy; Holmes; Herbert Hoover, Jr.; the Automotive Club of Southern California; that type of people, they ran southern California. They had the money. They had the mouth, the paper. They ran it. [William Randolph] Hearst was a secondary player. He had a paper, but he was secondary player. He wasn’t in the group. Hearst was more global.

These guys worried about everything south of the Tehachapi Mountains. That’s all they worried about. They worried about water. They worried about developments. They’ve made movies about that. Most of it’s true. The Southern Pacific was the big power player, but these guys were trying to upset the powers of the Southern Pacific to a degree. Holmes Tuttle came out of that power struggle, that power group.

He was a guy who would work hard. Asa Call was the brains. Holmes was the Stu Spencer, the guy that went out and made it happen. He was aggressive and he played a role. He started playing a role in the political process in the ’50s, post Earl Warren. None of these guys were involved with Earl Warren to any degree. But after Earl Warren and Nixon, they were players there. They never were in love with Nixon, but they were pragmatic. The Chandlers were in love with Nixon, and a few others, but with these bunch of guys, Ace would like Nixon. Holmes was the new conservative and Nixon was a different old conservative.

There were little differences there. Holmes emerged in the new conservative element and was heavily involved in the Goldwater campaign of ’64. Of course that’s a whole ’nother story. When Nixon went down the tube all of a sudden—it was lying there latent in the Goldwater movement and they were waiting for Nixon to get beat and when he did [sound effect]—here they were up in your face.

Reagan was the first legitimate person that Holmes was absolutely, totally, in synch with, and who he totally loved.

On Ron and Nancy:

Here’s an important point in my story. We met with the Reagans. The Reagans are a team politically. He would have never made the governorship without her. He would have never been victorious in the presidential race without her. They went into everything as a team.

It was a great love affair, is a great love affair. Early on I thought it was a lot of Hollywood stuff. I really did. I could give you anecdotes of her taking him to the train when he had to go to Phoenix because they didn’t fly in those days, or to Flagstaff to do the filming of the last segments of that western he was doing. We’d be in Union Station in L.A. at nine o’clock at night. They’re standing there kissing good-bye and it goes on and it goes on and it goes on. I’m embarrassed and I’m saying, Wow. It was just like a scene out of Hollywood in the 1930s, late ’30s, ’40s. I tell you that, but then I tell you now twenty-five, thirty, forty years later, whatever it is, it was a love affair. It was not Hollywood.

At that time I thought, oh, boy. It’s not only a partnership, it’s a great love affair. She was in every meeting that Bill and I were at with Reagan, discussing things, us asking questions, with him asking us questions. The curve of her involvement over the years was interesting because she was in her 40s then probably. She always lied about her age so I can’t tell you exactly, but she was somewhere around 45, I’d guess. She was quiet. With those big eyes of hers, she’d be watching you. Every now and then she’d ask a question, but not too often.

As time went on—I’m talking about years—she grew more and more vocal. But she was on a learning curve politically. She learned. She’s a very smart politician. She thinks very well politically. She thinks much more politically than he thinks. I think it’s important that Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan were the team that went to the Governor’s office and that went to the White House. They did it together. They always turned inward toward each other in times of crisis. She evolved a role out of it, her role. No one else will say this, but I say this: she was the personnel director.

She didn’t have anything to do with policy. She’d say something every now and then and he’d look at her and say, Hey, Mommy, that’s my role. She’d shut up. But when it came to who is the Chief of Staff, who is the political director, who is the press secretary, she had input because he didn’t like personnel decisions. Take the best example, Taft Schreiber, who was his agent out at Universal for years, and Lew Wasserman. After we signed on, Taft was in this group of finance guys and he said to me, Kid, we’ve got to have lunch.

I had lunch with Taft and he proceeded to tell me, You’re going to have to fire a lot of people. I said, What do you mean? He said, Ron— meaning Reagan—has never fired anybody in his life. He said, I’ve fired hundreds of people. He’s never fired anybody. I laughed. I said to myself, Taft’s overstating the case. Taft was right. I fired a lot of people after that.

Reagan hated personnel problems. He hated to see differences of opinion among his staff. His line was, Come on, boys. Go out and settle this and then come back. You’re going to have a lot of that in politics. You’re going to have a lot of that in government. That’s what makes the wheels go round. It doesn’t mean that they’re not friends or anything. They have differences of opinion, but Reagan didn’t like that too much, especially over the minutia, and it usually happens over the minutia.

The sum total of Reagan:

The sum total of him is simply this: here’s a man who had a basic belief, who thought America was a wonderful, great country. I don’t think you can go back through 43 Presidents and find a President of the United States who came from as much poverty as Reagan came from; income-wise, dysfunctional families. I can’t quite remember where [Harry] Truman came from, but you’re not going to find one.

This guy came from an alcoholic family, no money, no nothing. He was a kid who was a dreamer. He dreamed dreams and dreamed big dreams and went out to fulfill those dreams with his life and he did it. As he moved down his career and got really involved in the ideological side of the political spectrum, which is where he started, he had real concerns about all this leaving us because of communism.

You look back—some of it sounds a little silly—but at the time there was perceived all kinds of threats, all over the world about communism moving into Asia, moving into Africa. That was the driving force behind his political participations. It was the only thing that he really thought about in depth, intellectualized, thought about what you can do, what you can’t do, how you can do it.

With everything else, from welfare to taxation, he went through the motions. Now, this is me talking, but every night when he went to bed, he was thinking of some way of getting [Leonid Ilyich] Brezhnev or somebody in the corner. He told me this prior to the beginning of the presidency. Because I asked questions like, What the hell do you want this job for?

I’d get the speech and the program on communism. He could quote me numbers, figures. He’d say, We’ve got to build our defenses until they’re scary. Their economy is going down and it’s going to get worse. I’m simplifying our discussion. He watched and he fought for defense. God, he fought for defense. He cut here, he cut there for more defense. He took a lot of heat for it. All the time he delivered, in his mind, the message to Russia, we’re not going to back off. We’ll out-bomb you. We’ll out-do everything to you.

His backside knew that we have the resources, this country has the resources and the Russians don’t. If they try to keep up with us defensively, they’re going to be in poverty. They’re going to be economically dead and an economically dead country can only do one of two things, either spring the bomb or come to the table. He was willing to roll those dice because he absolutely had an utter fear of the consequences of nuclear warfare.

Again he was lucky. He couldn’t deal with Brezhnev. He was over the hill and out of it. [Yuri Vladimirovich] Andropov was gone, dead. Reagan lucked out. In comes this guy [Mikhail] Gorbachev who was smart enough to see the trend in his own country. He started talking with Reagan about cutting a deal. That’s what it got down to. In that context Reagan was very benevolent. He was willing to give up a lot. If this guy was serious and willing to go down this road, he was willing to give up things to get the job done, which was to get rid of the cold war. To him the cold war was the threat of nuclear holocaust in this country and other countries.

That was a dream that he had before he was in the presidency. These words I’m giving you and interpreting for you were given to me prior to his election to the presidency. If you do a lot of research, you’ll see that he was always asking questions of the intelligence people, What’s the state of the economy in Russia? He must’ve had a Dow Jones bottom line in his mind—what he thought it was going to take to do it—because he always knew how many nukes we had and where they were. He was really into this.

Young

Does that mean that Reagan was a visionary?

Spencer

I don’t know. He was a dreamer. He was a dreamer. He dreamed that he was going to be the best sportscaster in America, that he was going to be one of the better actors in Hollywood. You know he got tired of playing the bad guy alongside Errol Flynn, who got the women all the time. But he still dreamed big dreams. That’s the way he was.

On Reagan’s interpersonal style:

Young

He was good at communications obviously. How was he at working the room with politicians?

Spencer

Terrible. Ronald Reagan is a shy person. People don’t understand this. He was not an introvert. Nixon was almost an introvert and paranoid. That’s a bad combination. Reagan was shy. People who I met through the years said to me, I saw President Reagan at this, or I saw President Reagan one-on-one, two or three people in the Oval Office, or something. He never talked about anything substantive. He just told jokes.

Ronald Reagan used his humor and his ability to break the ice. He wasn’t comfortable with you and you coming in the Oval Office with strangers and talking.

Number one, he’s not going to tell you about what he’s doing. He doesn’t think it’s any of your damn business. Secondly, he’s not comfortable and so he uses his humor. He can do dialects. I mean the Jewish dialect, a gay dialect. He can tell an Irish ethnic joke. The guy was just unbelievably good at it and he’d break the ice with it. You’d listen to him. But if you were that type of person, you’d walk out of there and you’d say, What the hell were we talking about? He didn’t tell me anything.“

The Reagans had very few friends:

The Reagans never had a lot of friends. I cannot sit here today and tell you of a good, close, personal friend. They had each other and a lot of acquaintances. Maybe Robert Taylor was, maybe Jimmy Stewart was, some of those people. Maybe Charlie Wick and his wife, but other than that, I don’t know of any that they had. The Tuttles? They were not what you’d call close friends of theirs. They did things together but . . . it was he and Nancy.

An aside on Jimmy Carter:

The primary campaign for Jimmy Carter, 1976, was one of the best campaigns I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. They did an outstanding job. The guy in January was nine per cent in the polls in terms of his name ID. He ends up getting the nomination. Lots of things had to go right for them. Lots of breaks they had to get, breaks that they didn’t create, but they got them.

All that considered, the primary campaign was just an outstanding one. It was a lot of Jimmy Carter’s effort. He worked his tail off. Things kept setting up for him. The Kennedys kept vacillating and going this way and that. Everything kept setting up for him. They ran an outstanding campaign.

They had problems in ’80 because issues caught up with them. Their governance was not as good as their ability to run, which happens. I attribute most of it to his micromanagement. All of the Reagan people learned a lot from watching that because we had the opposite. [laughs]

The whole thing is great, on Bush, Dan Quayle, Clinton, Thatcher, it’s like 129 pages long.

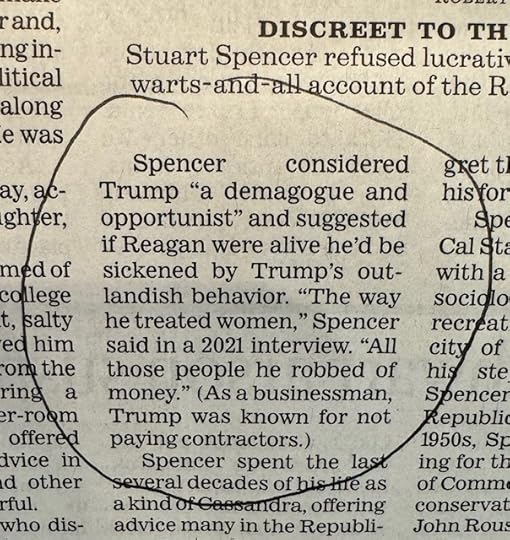

Two items to note from the obituary, by Mark A. Barabak:

and:

Spencer voted third party in 2016, for Joe Biden in 2020 and for Kamala Harris in 2024.

Some final advice from Spencer:

Finally I gave some major paper interview. It was on the plane. Marilyn [Quayle] was there and Dan Quayle was there. I was here and the press guy was here. The press guy starts out kind of warm and fuzzy and he says, Who are your favorite authors? He looks at Marilyn, and he says, Who are my favorite authors? Oh, God.

The second question is something about music. My position is, if you really haven’t thought about it in your own life, about who your favorite authors are, you can always say [Ernest] Hemingway. There are some names out there that you can use. If it’s music, you can say the Grateful Dead. Say anything you want to and think about it afterwards. I was wrong, I like this guy better.