Steve Hely's Blog, page 11

October 7, 2024

September 30, 2024

Memphis/Atlanta

Had a chance to see Memphis from 34k feet the other day on my way to Atlanta to show Common Side Effects at SCAD Animation Fest.

You can orient off the Bass Pro Pyramid there.

Spending a week living out of The Peabody Hotel in Memphis some years ago, now that was a special treat. A chopped chicken sandwich from Charlie Vergos’ Rendevous, enjoyed with a nice red wine while sitting in the lobby observing the ducks and the people? The ducks are tamer!

Well anyway after passing Memphis we flew right into the swirl of Helene.

Flying into a hurricane is a solved problem I guess, no one even fussed too much.

When the rain cleared up saw enough of Atlanta to conclude: I like it! Seems like a place where a person could just vibe.

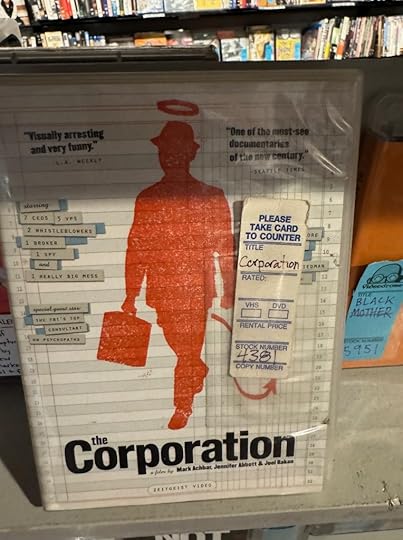

At Videodrome took a photo of a movie I’d like to see:

September 28, 2024

1st Australian Division

The 1st Australian Division was thrown in at Pozières on the Somme in mid July 1916 repeatedly to attack a high ridge. The Australians came out on September 4, having suffered 23,000 casualties. The Australian Official History could not hide its disdain and anger afterward:

To throw the several parts of an army corps, brigade after brigade … twenty times in succession against one of the strongest points in the enemy’s defence, may certainly be described as “methodical,” but the claim that it was economic is entirely unjustified.

(That’s from Eksteins, Rites of Spring.)

from Wikipedia:

Throughout the course of the war, the division suffered losses of around 15,000 men killed and 35,000 wounded, out of the 80,000 men that served in its ranks.

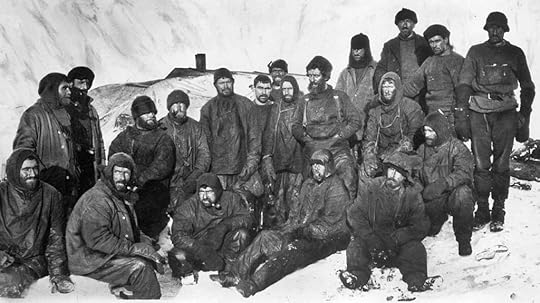

Frank Hurley took the above photograph, which I found at the Wiki page for 1st Australian Division. Frank Hurley was busy in the 19teens. Two years earlier he was in Antarctica taking this one, of The Endurance:

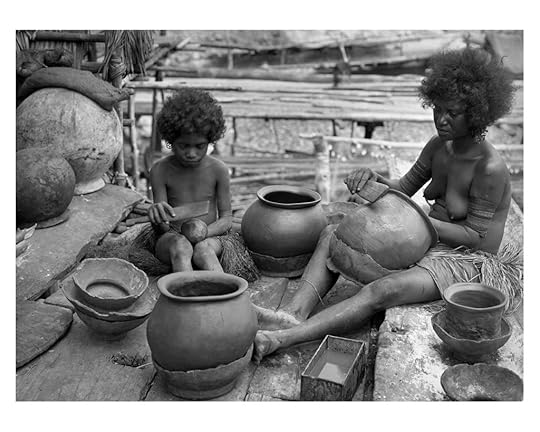

Frank Hurley also took extensive photographs in the Pacific, including Papua New Guinea:

Back to Antarctica, here is Blizzard the pup.

September 24, 2024

Slam on California

At the end of July 1914, Rupert Brooke, alarmed by the heightening European crisis, wrote to his friend Edward Marsh, “And I’m anxious that England may act rightly.” But what did it mean to “act rightly”? Another letter, a few days later, in which Brooke described an outing into the countryside, hinted in a general way at his own response to this question:

I’m a Warwickshire man. Don’t talk to me of Dartmoor or Snowden or the Thames or the lakes. I know the heart of England. It has a hedgy, warm bountiful dimpled air. Baby fields run up and down the little hills, and all the roads wiggle with pleasure. There’s a spirit of rare homeliness about the houses and the countryside, earthy, unec-centric yet elusive, fresh, meadowy, gaily gentle.. Of California the other States in America have this proverb: “Flowers without scent, birds without song, men without honour, and women without virtue” — and at least three of the four sections of this proverb I know very well to be true. But Warwickshire is the exact opposite of that. Here the flowers smell of heaven; there are no such larks as ours, and no such nightingales; the men pay more than they owe; and the women have very great and wonderful virtue, and that, mind you, no means through the mere absence of trial. In Warwickshire there are butterflies all the year round and a full moon every night…

Shakespeare and I are Warwickshire yokels. What a country!’

Aware of his sentimentality he went on to say, “This is nonsense,”

September 23, 2024

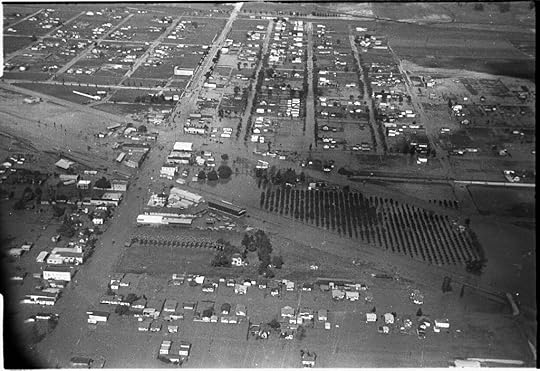

North Hollywood flooded, 1938

I found that here, it’s at the UCLA Digital Collection.

In the early 19th century, the river turned southwest after leaving the Glendale Narrows, where it joined Ballona Creek and discharged into Santa Monica Bay in present Marina del Rey. However, this account is challenged by Col. J. J. Warner, in his Historical Sketch of Los Angeles County:

“…until 1825 it was seldom, if in any year, that the river discharged even during the rainy season its waters into the sea. Instead of having a river way to the sea, the waters spread over the country, filling the depressions in the surface and forming lakes, ponds and marshes. The river water, if any, that reached the ocean drained off from the land at so many places, and in such small volumes, that no channel existed until the flood of 1825, which, by cutting a river way to tide water, drained the marsh land and caused the forests to disappear.”

September 21, 2024

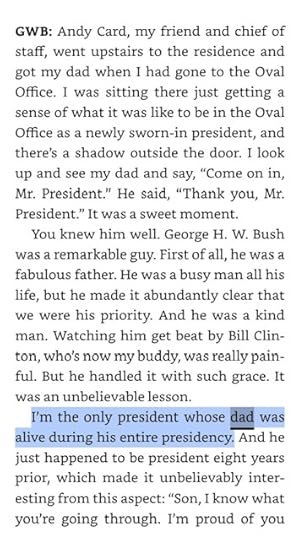

Presidential Dad Trivia

(source)

George W. Bush, interviewed by David Rubinstein of the Carlyle Group in his book The Highest Calling: Conversations on the American Presidency.

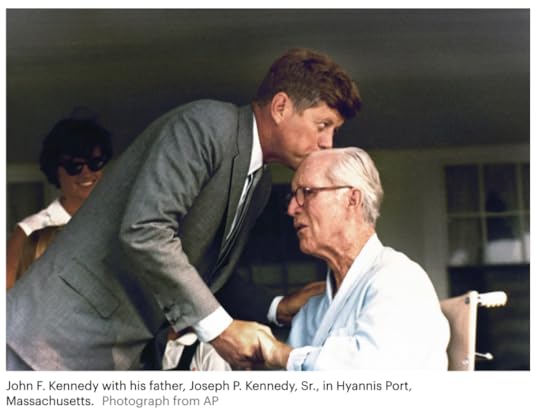

This is not accurate. There was Joseph Kennedy:

who outlived three of his sons. Nathaniel Fillmore lived to be 91, and saw all of son Millard’s presidency. George Harding outlived son Warren, he died in Santa Ana, California.

In his biography of Warren G. Harding, Charles L. Mee describes Tryon Harding as “a small, idle, shiftless, impractical, lazy, daydreaming, catnapping fellow whose eye was always on the main chance”.

The W. Bush interview is frustrating to those of us who think he ruined everything:

How about this:

Well, I’m glad it was nice for you. (Genuinely, I am. The guy has charm, despite the catastrophes. What does that tell us? How can we profit from knowing that a president will come along the consequences of whom are awful and we still are lured in?)

W. does seem to take some responsibility here, on the bank bailouts:

W. Bush seems like a guy who says, well, I made the best decision under the circumstances and then shrugs at the consequences. That was the vibe I got from his book, Decision Points. Just because the consequences are appalling, doesn’t mean it was a bad decision. They no doubt taught him that at Harvard Business School.

In his Miller Center interview, Karl Rove tells a story from the transition meeting with Bill Clinton:

Riley

So this was the one personal thing. Who came up with the line, “When I was young and irresponsible, I was young and irresponsible”?

Rove

Him.

Riley

Him?

Rove

Yes. As he’s also the author—He stole the idea—of “compassionate conservatism.” When we saw Clinton after the election, he said [imitating Clinton], “When I heard you say that phrase, ‘compassionate conservatism,’ George, I knew we were in deep trouble. That’s brilliant, it was just brilliant.”

W communications guy Dan Bartlett tells another:

When they had their transition meeting, as always happens, he asked him. “How’d you get better at it?” Clinton said, “Two things. First, you’re going to give a lot of speeches, so just practice. Practice more than anything else is going to make you better. Secondly, I learned how to take my time and to pause.” He told him a trick. He said, “On every other sentence or maybe every third sentence, it was one or the other, when I hit a period I would count in my head—one thousand one, one thousand two, one thousand three—before I’d read the next sentence. It will be hard for you to pull that off, because it feels like an eternity.”

I don’t know if you’ve done public speaking. I do it now. To master the pause, which Clinton now is brilliant at. He said, “Pacing is everything in speechwriting.” So he took that to heart. He took it, but what Clinton was good at, which Bush was never good at, was that while he was not a gifted speaker, he was an authentic communicator. It was always up to us to make sure that he really believed—Clinton could make the signing of a post office bill like the Gettysburg Address. He could take anything and at a moment’s notice turn it around. You knew when Bush was mailing one in.

September 15, 2024

San Francisco (and California) Politics

When former Assembly Speaker Antonio Villaraigosa lost a campaign to become mayor of Los Angeles in June, then-Speaker Robert Hertzberg named him to the California Medical Assistance Commission, where he could earn $99,000 a year, plus benefits, working a few hours each month.

Former Assemblyman Richard Alatorre, D-Los Angeles, who served in the legislature with Senate President Pro Tem John Burton in the 1970s, was out of public office and the target of a federal corruption probe two years ago when Burton placed him on the Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board. His salary: $114,180 a year plus benefits.

from SF Gate, 2002.

Assembly Speaker Willie Brown, continuing his rush to hand out patronage jobs while he retains his powerful post, has given high-paying appointments to his former law associate and a former Alameda County prosecutor who is Brown’s frequent companion.

Brown, exercising his power even as his speakership seems near an end, named attorney Kamala Harris to the California Medical Assistance Commission, a job that pays $72,000 a year.

Harris, a former deputy district attorney in Alameda County, was described by several people at the Capitol as Brown’s girlfriend. In March, San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen called her “the Speaker’s new steady.” Harris declined to be interviewed Monday and Brown’s spokeswoman did not return phone calls.

Harris accepted the appointment last week after serving six months as Brown’s appointee to the Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board, which pays $97,088 a year. After Harris resigned from the unemployment board last week, Brown replaced her with Philip S. Ryan, a lawyer and longtime friend and business associate.

Last week, Brown also appointed Janet Gotch, wife of retiring Assemblyman Mike Gotch of San Diego, to the $95,000-a-year Integrated Waste Management Board, which oversees garbage disposal in California.

from Los Angeles Times, 1994. In fairness sitting through those hearings is probably very boring!

The story goes that in 2015 Gavin Newsom and Kamala Harris, maybe encouraged by various Democratic fundraisers and power brokers, cut a deal where she would run for Senate and he would run for Governor in 2018:

The early-2015 understanding between the two San Francisco Democrats, both with campaigns managed by the same San Francisco political consulting firm, was this: To avoid a brutal fight over the Senate seat being vacated by the retiring Barbara Boxer, Newsom would stay out of the 2016 Senate race and concentrate on running for governor two years later.

A LA Times article about the story that Gavin Newsom might be unhappy with subsequent developments (it’s not over yet Gavin!) led me to this 2015 article about why San Francisco has produced so many prominent state leaders. It’s a question we’ve pondered before:

There is nothing mysterious about San Francisco’s export of high-profile politicians, nothing like the alchemy of air and water that produces the distinctive tang of its signature sourdough bread.

Simply put, it’s fierce competition, at virtually every level, starting with the leadership of its political clubs and spreading to the lowliest contests for elected office on up to races for the Legislature and Congress.

Where San Diego and Los Angeles lie back, most of their residents scarcely interested in politics, San Francisco leans in: chin out, elbows wide and sharp.

“There is a culture here of fighting over just about everything in the public space,” said Eric Jaye, another of the city’s veteran political strategists, from global issues like the Middle East to protecting the neighborhood coffee shop from an onslaught of franchised beans….

from earlier in the same piece (by Mark Z. Barabak):

San Francisco is the closest thing to an East Coast enclave set along the Pacific, a place, like New York or Boston, where politics is a passion, a sport, something everyday people fuss and fight and scheme over.

As blue (politically) as San Francisco Bay, the city has 27 officially chartered Democratic Party chapters, among them the Raoul Wallenberg Jewish Democratic Club, the Filipino American Democratic Club, the Black Young Democrats of San Francisco and the Harvey Milk LGBT Democratic Club. That works out to roughly one party franchise every few blocks.

There are countless more neighborhood councils, civic associations, interest groups — branches of the Sierra Club, the NAACP and the like — all clamoring for their particular agendas.

“It’s a city where people have always been able to be loud and proud about who they are, not just as individuals but as a group or a community,” said Ace Smith, a Democratic strategist who has decades of experience running San Francisco campaigns.

The result is a kind of hyper-democracy and political forge that has fashioned some of California’s most powerful and enduring elected leaders, in numbers far out of proportion to the city’s relative pint size.

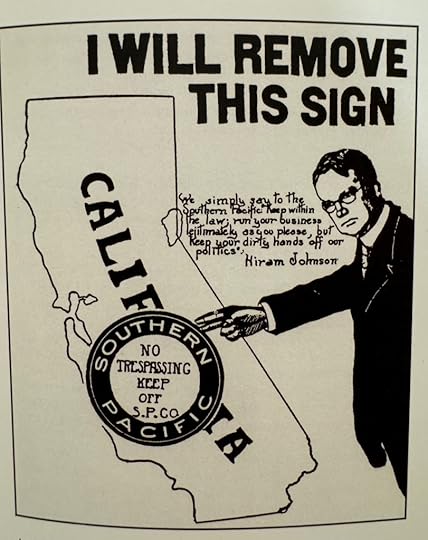

A very short history of California’s politics might go something like this: California wanted to get into the union without going through the territorial stage, so they sorta rushed through a constitutional convention (John Sutter himself was there). In the compromise of 1850, one of the deals involving slave and free states, California got brought in. The US wanted a lock on that gold. During the Civil War California stayed in the Union (barely). After the Civil War, the major power in the state was the railroad barons, the Big Four, who were so powerful that they provoked a progressive, democratic backlash, personified by Hiram Johnson.

(He looks like Dwight Shrute, no?)

Here’s Reagan’s guy Stuart Spencer talking about Hiram:

They didn’t do a lot of candidate work, but they did a lot of what we call proposition work in California. Under the reforms of Hiram Johnson, we were a unique state at that time. We were for years. You could put practically anything on the ballot and have it decided there instead of the legislature.

You can also read Leon Panetta, who began as a Republican but became a prominent Democrat, talking about Hiram:

I was raised in a progressive Republicanism that used to be the case in California. It began with Hiram Johnson. It was a tradition that was carried on by people like Earl Warren and Tom Kuchel, whom I worked for, and Goodwin Knight and others. Because of cross filing, because of the traditions of California.

As a result of all this balloting California politics gets pretty complicated. Our state constitution is 76,930 words long. Novel length. (Although it’s not even close to the length of the longest, which is…. can you guess it?….

Alabama, at over 402,000 words. Gotta look into how that came to be. Seems to be because it makes a lot of specific rules for specific municipalities.)

At the moment we’re a one party state, probably because the second to last Republican governor, Pete Wilson, made his big issue immigration (anti). He actually won big on that, with Proposition 187 in 1994. The voters went for that in a big way, but it then got tied up in the courts, and the next Democratic governor, Grey Davis, stopped pursuing the implementation.

Noting a rapid increase in the number of Latinos voting in California elections, some analysts cite Wilson and the Republican Party’s embrace of Proposition 187 as a cause of the subsequent failure of the party to win statewide elections.

California today is maybe 26% immigrants. The most recent Republican governor was an immigrant. He won after Grey Davis was recalled (a Hiram Johnson reform). We might be tempted to treat that election as a special circumstance, as he was famous movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger, but then again another famous movie star, Ronald Reagan, had been elected governor before. And George Murphy had been elected senator. Do you need a certain glam quality to succeed in California politics?

Two Californians have become president, although only one, Nixon, was born in California. A third Californian and second native born Californian has a real good shot right now. We’re rooting for her!

September 14, 2024

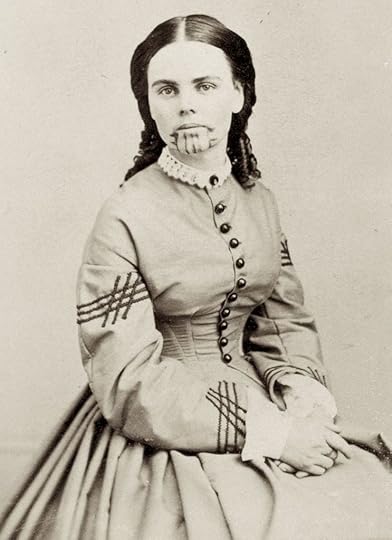

Spantsa / Olive Oatman

OTLTA is a new acronym I’d like to get going. It stands for “one thing led to another.” Here it is in context: OTLA and I’m reading about captivity narratives of the American West. Accounts by white people who were captured or taken in by native tribes.

Captivity narratives are a whole serious category of study for academic historians. I’d fear to get over my skis here. There were commercial and political incentives to make these narratives as lurid as possible. How much to trust any one account is a historical puzzle. But, we love those.

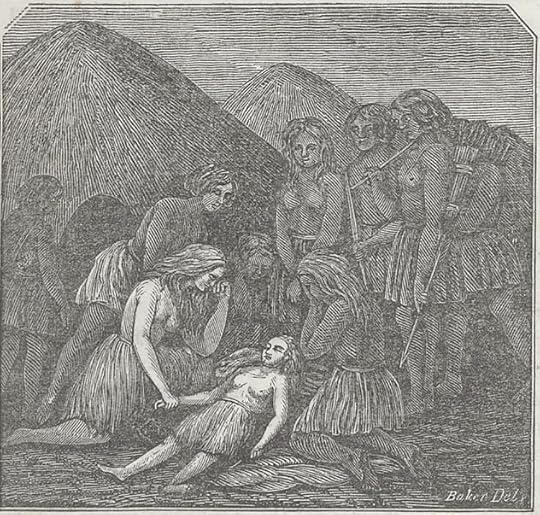

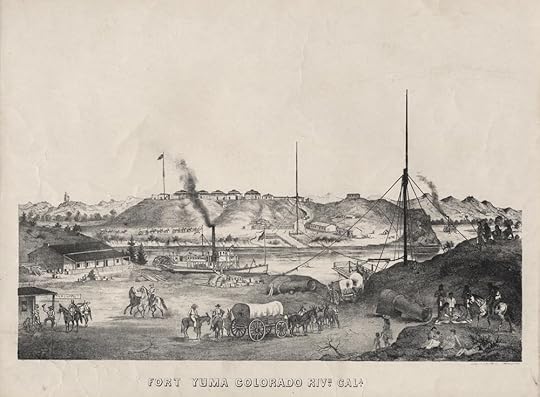

Take for example Olive Oatman. When she was fourteen she was traveling with her family, who were Brewsterites, an splinter group of Mormons. Their intended destination was Yuma, Arizona, on the Colorado River. On Saturday, March 8, 1851, some eighty miles east of Yuma, they encountered some Yavapai people. (Already we need a footnote: were they really Yavapai? There are papers on this topic.) Everyone in the party was killed except Olive and her younger sister Mary Ann.

The Yavapai kept them but eventually traded them to some Mohave people.

Mary Ann did not survive.

After about four years among the Mohave, the post commander at Fort Yuma, on the California side, heard about a white woman living out there and sent word that he’d like her back.

We pick up the rest from Wikipedia:

Inside the fort, Olive was surrounded by cheering people.

Olive’s childhood friend Susan Thompson, whom she befriended again at this time, stated many years later that she believed Olive was “grieving” upon her forced return because she had been married to a Mohave man and had given birth to two boys.

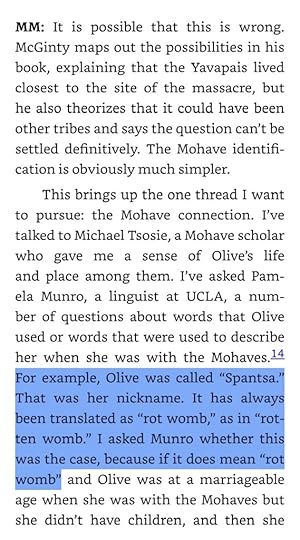

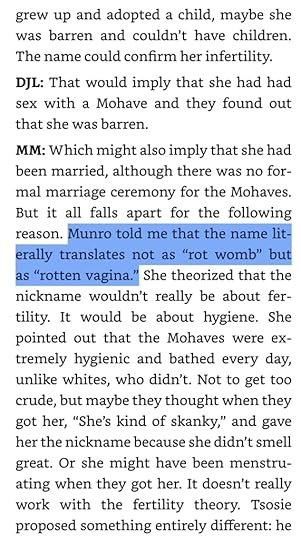

Olive, however, denied rumors during her lifetime that she either had been married to a Mohave or had been sexually mistreated by the Yavapai or Mohave. In Stratton’s book, she declared that “to the honor of these savages let it be said, they never offered the least unchaste abuse to me.” However, her nickname, Spantsa, may have meant “rotten womb” and implied that she was sexually active, although historians have argued that the name could have different meanings.[5]: 73–74 [19]

from Violent Encounters: Interviews on Western Massacres (University of Oklahoma Press), by Deborah and Jon Lawrence, an interview with Margot Mifflin, an associat professor of English at Lehman College of the City University of New York who also directs the Arts and Cultire program at CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism (“Her interest in tatoo art let to her work on the life of Olive Oatman.”):

History, getting towards the source, remains an engaging pastime.

I’ve been to a lot of California but I’ve never had the chance to visit Winterhaven, where we’d find the site of Fort Yuma. If I’m there I will surely check out the Museum of History in Granite:

Amazing if in four millennia the United States and the French Foreign Legion are remembered in equal proportion.

(User Kirs10 took that photo of the pyramid)

September 7, 2024

Conversations with Grant

After his Presidency Ulysses Grant took an around the world tour with his wife and the diplomat, librarian and scholar John Russell Young, who took notes on the trip and published them in a book.

The trip as recorded by Young is interesting but much of it was written for an audience that would never travel overseas. It was a ponderous, two-volume tome of over 1,300 pages with 800 engraved illustrations.

The good folks at Big Byte Press have taken the juiciest parts and compiled them into Conversations With Grant. (Note that this version does not include the famous conversation with Bismarck). I could spend a while with their various reprints of historical memoirs for Kindle. What a service. Here are some items we learn:

after the end of the Civil War, Grant wanted to keep going and invade Mexico:

“When our war ended,” said General Grant, “I urged upon President Johnson an immediate invasion of Mexico. I am not sure whether I wrote him or not, but I pressed the matter frequently upon Mr. Johnson and Mr. Seward [Secretary of State, William Seward]. You see, Napoleon in Mexico was really a part, and an active part, of the rebellion. His army was as much opposed to us as that of Kirby Smith. Even apart from his desire to establish a monarchy, and overthrow a friendly republic, against which every loyal American revolted, there was the active co-operation between the French and the rebels on the Rio Grande which made it an act of war. I believed then, and I believe now, that we had a just cause of war with Maximilian, and with Napoleon if he supported him—with Napoleon especially, as he was the head of the whole business. We were so placed that we were bound to fight him. I sent Sheridan off to the Rio Grande. I sent him post haste, not giving him time to participate in the farewell review. My plan was to give him a corps, have him cross the Rio Grande, join Juarez, and attack Maximilian. With his corps he could have walked over Mexico. Mr. Johnson seemed to favor my plan, but Mr. Seward was opposed, and his opposition was decisive.” The remark was made that such a move necessarily meant a war with France. “I suppose so,” said the General. “But with the army that we had on both sides at the close of the war, what did we care for Napoleon? Unless Napoleon surrendered his Mexican project, I was for fighting Napoleon. There never was a more just cause for war than what Napoleon gave us. With our army we could do as we pleased. We had a victorious army, trained in four years of war, and we had the whole South to recruit from. I had that in my mind when I proposed the advance on Mexico. I wanted to employ and occupy the Southern army. We had destroyed the career of many of them at home, and I wanted them to go to Mexico. I am not sure now that I was sound in that conclusion. I have thought that their devotion to slavery and their familiarity with the institution would have led them to introduce slavery, or something like it, into Mexico, which would have been a calamity. Still, my plan at the time was to induce the Southern troops to go to Mexico, to go as soldiers under Sheridan, and remain as settlers. I was especially anxious that Kirby Smith with his command should go over. Kirby Smith had not surrendered, and I was not sure that he would not give us trouble before surrendering. Mexico seemed an outlet for the disappointed and dangerous elements in the South, elements brave and warlike and energetic enough, and with their share of the best qualities of the Anglo-Saxon character, but irreconcilable in their hostility to the Union. As our people had saved the Union and meant to keep it, and manage it as we liked, and not as they liked, it seemed to me that the best place for our defeated friends was Mexico. It was better for them and better for us. I tried to make Lee think so when he surrendered. They would have done perhaps as great a work in Mexico as has been done in California.” It was suggested that Mr. Seward’s objection to attack Napoleon was his dread of another war. The General said: “No one dreaded war more than I did. I had more than I wanted. But the war would have been national, and we could have united both sections under one flag. The good results accruing from that would in themselves have compensated for another war, even if it had come, and such a war as it must have been under Sheridan and his army—short, quick, decisive, and assuredly triumphant. We could have marched from the Rio Grande to Mexico without a serious battle.

although he thought the first Mexican War was bad:

I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico. I thought so at the time, when I was a youngster, only I had not moral courage enough to resign.

…The Mexicans are a good people. They live on little and work hard. They suffer from the influence of the Church, which, while I was in Mexico at least, was as bad as could be. The Mexicans were good soldiers, but badly commanded. The country is rich, and if the people could be assured a good government, they would prosper. See what we have made of Texas and California—empires. There are the same materials for new empires in Mexico.

on Napoleon:

Of course the first emperor was a great genius, but one of the most selfish and cruel men in history. Outside of his military skill I do not see a redeeming trait in his character. He abused France for his own ends, and brought incredible disasters upon his country to gratify his selfish ambition I do not think any genius can excuse a crime like that.

He never wanted to go to West Point, or be in the army at all:

was never more delighted at anything,” said the General, “than the close of the war. I never liked service in the army—not as a young officer. I did not want to go to West Point. My appointment was an accident, and my father had to use his authority to make me go. If I could have escaped West Point without bringing myself into disgrace at home, I would have done so. I remember about the time I entered the academy there were debates in Congress over a proposal to abolish West Point. I used to look over the papers, and read the Congress reports with eagerness, to see the progress the bill made, and hoping to hear that the school had been abolished, and that I could go home to my father without being in disgrace. I never went into a battle willingly or with enthusiasm. I was always glad when a battle was over. I never want to command another army. I take no interest in armies. When the Duke of Cambridge asked me to review his troops at Aldershott I told his Royal Highness that the one thing I never wanted to see again was a military parade. When I resigned from the army and went to a farm I was happy.

The Battle of St. Louis was narrowly avoided:

there was some splendid work done in Missouri, and especially in St. Louis, in the earliest days of the war, which people have now almost forgotten. If St. Louis had been captured by the rebels it would have made a vast difference in our war. It would have been a terrible task to have recaptured St. Louis—one of the most difficult that could be given to any military man. Instead of a campaign before Vicksburg, it would have been a campaign before St. Louis.

He loved Oakland, and Yosemite:

The San Francisco that he had known in the early days had vanished, and even the aspect of nature had changed; for the resolute men who are building the metropolis of the Pacific have absorbed the waters and torn down the hills to make their way.

…

Oakland is a suburb of San Francisco, and is certainly one of the most beautiful cities I have seen in my journey around the world.

…

So much has been written about the Yosemite that I venture but one remark: that having seen most of the sights that attract travelers in India, Asia, and Europe, it stands unparalleled as a rapturous vision of beauty and splendor.

He wanted to live in California:

The only promotion that I ever rejoiced in was when I was made major-general in the regular army. I was happy over that, because it made me the junior major-general, and I hoped, when the war was over, that I could live in California. I had been yearning for the opportunity to return to California, and I saw it in that promotion. When I was given a higher command, I was sorry, because it involved a residence in Washington, which, at that time, of all places in the country I disliked, and it dissolved my hopes of a return to the Pacific coast. I came to like Washington, however, when I knew it.

He had some reservations about Lee as a general:

Lee was of a slow, conservative, cautious nature, without imagination or humor, always the same, with grave dignity. I never could see in his achievements what justifies his reputation. The illusion that nothing but heavy odds beat him will not stand the ultimate light of history. I know it is not true. Lee was a good deal of a headquarters general; a desk general, from what I can hear, and from what his officers say. He was almost too old for active service—the best service in the field. At the time of the surrender he was fifty-eight or fifty-nine and I was forty-three. His officers used to say that he posed himself, that he was retiring and exclusive, and that his headquarters were difficult of access. I remember when the commissioners came through our lines to treat, just before the surrender, that one of them remarked on the great difference between our headquarters and Lee’s. I always kept open house at head-quarters, so far as the army was concerned.

On Shiloh:

“No battle,” said General Grant on one occasion, “has been more discussed than Shiloh-none in my career. The correspondents and papers at the time all said that Shiloh was a surprise-that our men were killed over their coffee, and so on.

There was no surprise about it, except,” said the General, with a smile, “perhaps to the newspaper correspondents. We had been skirmishing for two days before we were attacked. At night, when but a small portion of Buell’s army had crossed to the west bank of the Tennessee River, I was so well satisfied with the result, and so certain that I would beat Beauregard, even without Buell’s aid, that I went in person to each division commander and ordered an advance along the line at four in the morning. Shiloh was one of the most important battles in the war. It was there that our Western soldiers first met the enemy in a pitched battle. From that day they never feared to fight the enemy, and never went into action without feeling sure they would win. Shiloh broke the prestige of the Southern Confederacy so far as our Western army was con-cerned. Sherman was the hero of Shiloh.

He really commanded two divisions-his own and McClernand’s-and proved himself to be a consummate soldier. Nothing could be finer than his work at Shiloh, and yet Shiloh was belittled by our Northern people so that many people look at it as a defeat.

September 3, 2024

Amazing things happening in the Vertigo Sucks community

The comments coming to life on our 2013 post. To be clear, our problem isn’t so much with Vertigo itself as with film critics who overhype it, hurting rather than helping the cause of old movie appreciation.