Chris Chelser's Blog, page 6

July 17, 2017

Review: Kalbrandt Institute

“My first reaction was “Finally, a book that treats ghosts and other phenomena as real”. The goosebumps do not come from wondering about whether or not there are ghosts, so one can delve into the story head-first and see what develops. From other books by Chelser I had already come to expect a high level of wielding the English language. I will enjoy going back to these stories to re-read and discover more nuances.”

– Edith Gessner, reader

Het bericht Review: Kalbrandt Institute verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

Review: Kalbrandt Institute

“My favourite story must have been the one in Paris. Those two ghosts had won my heart from the first moment. I was actually quite cross that they should be exorcised. If one story already can make me as the reader instantly relate to characters depicted, then the rest of the book cannot be bad. And it is not; far from it.”

– Elke Niclaesen, reader

Het bericht Review: Kalbrandt Institute verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

June 20, 2017

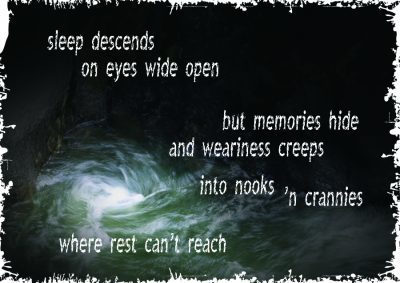

Soulless Cry #34 as print

Perhaps I should put these up for order somewhere? I do plan on bringing some to the next fair, but for many of you that might be too much of a distance… What do you think?

Het bericht Soulless Cry #34 as print verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

June 9, 2017

In The Dark, There Be Dragons

Lately, I’ve been fully immerse in the Starz show Black Sails, the 4-season prequel to R.L. Stevenson’s Treasure Island which tells the story of Captain Flint, Billy Bones and Long John Silver in a terrifyingly realistic historical setting. There be dragons? Oh yes!

Beyond the swashbuckling, so much of this show resonates with what I care about as a storyteller that I even re-watch it in binge sessions. Don’t worry. I will spare you harping on about my admiration for the storytelling, the characters, the actors, the set and essentially everything else that is brilliant about this production.

Except this bit where Captain Flint (Toby Stephens), dead-tired of fighting against “civilised society”, proceeds to take the words right out of my mouth [no spoilers]:

http://chrischelser.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/In-the-dark-thre-be-dragons-Black-Sails-exerpt-S4E10.mp4

They paint the world full of shadows, and then tell their children to stay close to the light. Their light. Their reasons, their judgements. Because in the darkness, there be dragons.

But it isn’t true. We can prove that it isn’t true.

In the dark, there is discovery. There is possibility. There is freedom…in the dark. Once someone has illuminated it.

~ Captain Flint (Black Sails S4E10)

So embrace your nightmares. You won’t regret it.

Love,

Het bericht In The Dark, There Be Dragons verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

June 5, 2017

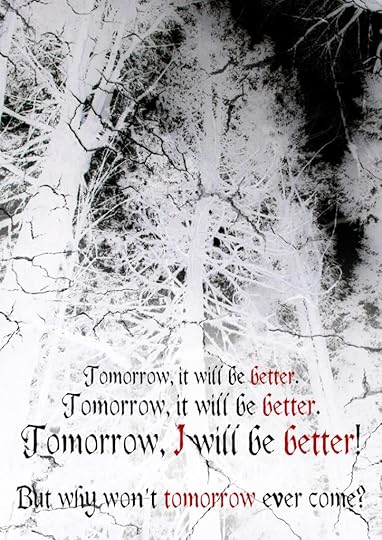

Art prints of the Soulless Cries

This idea crossed my mind a while ago. Why not make full-fledged, high-resolution prints for the Soulless Cries?

So now #70 looks like this:

What do you think? Should I make more of these? I can’t read mind, to please leave a comment below ;).

Het bericht Art prints of the Soulless Cries verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

May 2, 2017

Write Like It’s Business – Part IV

This series of blogposts shows creative writers how business management techniques apply to both the writing process and the storytelling process, and why the corporate world isn’t as alien at it seems.

(c) Dennis Skley via Flickr

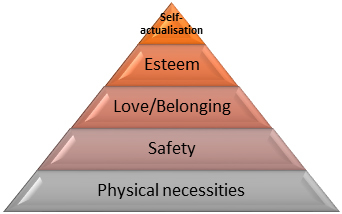

(c) Dennis Skley via FlickrAfter discussing various business management models in Part I, Part II and Part III of this series, let’s delve into creating good and bad conflict by applying Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs.

Hierarchy of Needs

The idea of this chiefly psychological model is that a person deprived of food and water will be less concerned with having a roof over his head than he is with finding physical sustenance. Once he has sustenance, he will be wanting shelter. Once he has shelter, he will long for company or a group to belong to. Once he belongs to a group, he will want to gain esteem inside and outside that group. And only someone who has those basic needs more or less fulfilled will be interested in actualising or transcending themselves.

As any model, this hierarchy is extremely simplified. How important each of the strata is, will vary from person to person based on their personality, culture and unique circumstances. For this reason, the hierarchy’s validity as a psychological model is questioned by some. Even so, it is my firm belief that it provides a viable outline for writers to work with.

Because the model holds true, in however broad a sense, for 99,9% of humanity. That includes you, your readers, and your human(oid) characters.

Maslow’s Storytelling Lessons…

Lesson 1: Needs are the foundation of conflict in storytelling. What does the character want? What happens when they’re up the pyramid and the lower layers get knocked out from under them? How do they respond? What will that do to (re)gain that which they need?

Lesson 2: When you write a non-human character, like an alien entity, you should ask yourself if they respond roughly in accordance with this hierarchy of needs (most of the early Star Trek and Star Wars aliens). Or are they truly alien to us in that they don’t understand this fundamental part of human psychology? (Later Star Trek franchises, Alien, Abyss). Such a creature is unpredictable for us and thus scary. But going that was has its limits, because…

Lesson 3: …your readers are human. If you wish them to care for your character, they must be able to empathise. Maslow’s hierarchy provides a blueprint of the most basic level of empathising: being deprived of love, safety, and food is something almost everyone can relate to. You needn’t be orphaned or widowed to know what heartbreak is. You needn’t have known actual starvation in order to relate to Robinson Crusoe. Imagination goes a long way.

Likewise, a character that doesn’t respond to this hierarchy is truly alien, and therefore difficult to relate to. That works for an antagonist, but not for a protagonist.

…And A Wise Word To Introvert Writers

Know why you’re writing. Most often people want to write a book for esteem or for self-actualisation, but in this we forget an important aspect: many writers are introverts and as such don’t care much about belonging to a group. Problem is, other people do.

At the very least, authors must interact with their readers if they wish to be in any way successful. The more ambitious must also find rapport with publishers, agents, guest blogs, etc. in order to advance their writing career.

When it comes to this, I’m just as guilty as anyone else hiding behind their keyboard. I’ve felt the consequences of being the lone wolf, and trust me: they are severe.

The reason for this is no more complex than instinct.

People are herd animals. By that instinct, anything that jeopardised the group is to be avoided. Individuals who do not wish to belong to our group – or any group – are rooted out and rejected by people who do have a herd-instinct. It’s not a conscious choice, but it’s what the human animal does.

You won’t find more readers if you shun talking to them.

So no matter how introvert you are, learn to socialise. Create a persona for yourself if you must, a mask to hide behind, but don’t try to avoid reaching out to others. You won’t find more readers if you shun them.

Model Behaviour

It is out job as storytellers to convince our audience. We share this with business managers, and common ground means common lessons. Sales people take courses in storytelling. Why don’t more writers take courses in management? If nothing else, studying books and models is a good start.

Self-publishing requires self-management. Self-management 101 says not to reinvent that wheel, but to hitch a ride on science’s “how to” wagon instead.

As for starting a conversation: what else would you like me to write about on this blog. Would you like to see more about how business science applies to writing and storytelling? Or about ghosts and history and about how I apply all of the above in my books? Or perhaps something entirely different?

Please let me know in the comments!

Until next time,

Het bericht Write Like It’s Business – Part IV verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

April 26, 2017

Write Like It’s Business – Part III

This series of blogposts shows creative writers how business management techniques apply to both the writing process and the storytelling process, and why the corporate world isn’t as alien at it seems.

(c) Dennis Skley via Flickr

(c) Dennis Skley via FlickrIn Part II of this series, we had a closer look the Deming’s “plan-do-check-act” cycle and how that relates to writers and their stories.

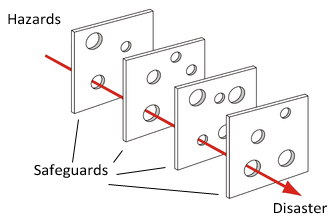

In this post, we will explore another indispensable model that every writer should use: James Reason’s model for avoiding disasters.

Swiss Cheese of Plot Holes

One of my favourite models is James Reason’s “Swiss Cheese” model of how accidents happen – and how they can be prevented. It’s standard material in the aviation industry, but it applies to any process where things can go wrong. Writing and storytelling included.

The model consists of various layers of safeguards (the cheese) to protect against hazards. However, no safety precaution is ever foolproof: every layer of protection has its own shortcomings (the holes).

Those inevitable shortcomings are acceptable, because the next safeguard will catch any hazard coming through. If not, then there is a third safeguard, etc. Only when the holes in ALL safeguards line up, a hazard can cause to a disaster.

What do slices of cheese have to do with writing, you ask? Imagine this:

Bad fiction, unfinished projects, devastating critiques, angry readers and heaps of rejection letters are a writer’s worst enemies. Our hazards, so to speak.

Clear theme, consistent plot, thorough research, good characterisations, interesting conflict, proper use of story structure and language – these are a writer’s safeguards to writing superb stories.

No author is perfect. We are all human, so our safeguards will have flaws like poor dialogues, unremarkable characters, blank settings and incredulous plot twists.

Despite a story’s faults, audiences are willing to forgive a lot if a story has other qualities that make up for the flaws. For example, poor dialogue can be forgiven if the conflict is compelling, and superior descriptions or good action can make up for inconsistent characters.

As long as we, the authors, put our safeguards to the best possible use, we run far less risk of our work being rejected or worse, ignored: our disaster.

Trust the cheese

There are many aspects to our writing, our stories, and our storytelling that catch or negate the flaws within each other. Audiences are more forgiving than you may think. How else can books like Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey, or superhero movies with massive consistency flaws be so popular? Whatever their shortcomings, they have sufficient strength to entice and enthral their audience all the same. And that audience loves them.

Writers know their work’s weak spots. Too often that is all they see, and it keeps them from publishing it. But your audience will recognise strengths you never even realised were there.

So next time you’re afraid to push the “send” button on a manuscript, trust the Swiss cheese and take the leap. Your audience will thank you for it.

Next week: cut your losses with Maslow!

Cheers,

Het bericht Write Like It’s Business – Part III verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

April 19, 2017

Write Like It’s Business – Part II

This series of blogposts shows creative writers how business management techniques apply to both the writing process and the storytelling process, and why the corporate world isn’t as alien at it seems.

(c) Dennis Skley via Flickr

(c) Dennis Skley via FlickrWriters and business people have more in common than we imagine. In Part I of this series, I discussed the merits of production planning for both the process of writing and publishing, but also how to keep the story itself on track.

In this post, we will explore another indispensable model that every writer should use.

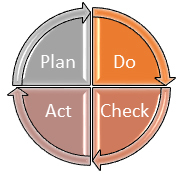

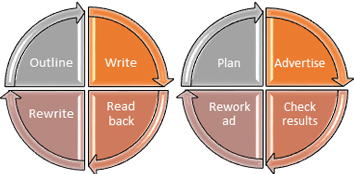

Deming Cycle For Writers

When you know what to look for, avoiding a pitfall is easy. You leap across the hole, pat yourself on the back, and as you square your shoulders to continue on your way… you fall down a second pit that you didn’t see.

Fool me once, shame on me. Fool me twice, still shame on me.

Since all people have a tendency to lay back after getting something right, business science employs the Deming Cycle of Continuous Improvement. If you have never heard that name, chances are you will still recognise its four stages:

You make a plan,

You do as you planned,

You check if what you did has the desired results,

You act upon that feedback to stay on the Plan.

People, situations and the world in general change constantly. So whenever you set a plan in motion, sooner or later it will run out of the ruts. Considering driving a car: even when you’re going straight ahead, you need to correct the steering wheel now and then before your run off the road and into something.

For some activities, this cycle comes natural. We do it in our writing, we are taught to apply it to our marketing strategies. Just think about it:

Yet it’s staggering how often people neglect those last two steps:

Writers let people read their book draft, but put off processing feedback they don’t like to hear;

Authors see their advertisement on Facebook didn’t get them new followers, so they abandon the idea of social media altogether instead of working on a formula that does yield results.

I’m guilty of this myself. Everyone is, no exceptions. But if we want to improve, not just as writers but as the entrepreneurs we must also be, then we need to put in the work. Constantly and relentlessly. No shortcuts.

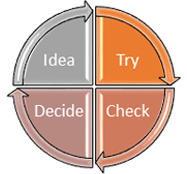

The usefulness of the Deming Cycle doesn’t end there. This extremely versatile model also helps to keep unexpected and undeveloped story ideas from ruining your work in progress:

You have a great idea for a scene/character/story/plot twist.

You try it out: visualise, daydream about how this idea affects your story, plot, characters, etc.

You check if this outcome improves the story.

You decide to implement the idea, amend it or toss it.

This simple four-step process can save you from writing an utterly unsalvageable first draft.

Tinkering with story ideas Deming-style can all take place in your mind. No need to spend hundreds of hours writing a book based on this “great idea” that in the end doesn’t work for your story’s message (also known as “theme”).

Still want to stretch a flawed draft to make it work? Then Reason’s Swiss cheese is your friend. More on that next week. Until then!

Het bericht Write Like It’s Business – Part II verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

April 13, 2017

Write Like It’s Business – Part I

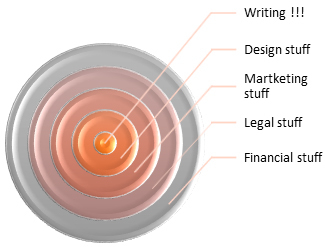

Never before has the writing business been more about business than it is now. Any author who wants to be published (again) needs to be an entrepreneur as much as a writer. Taxes, contracts, advertisement, PR… It doesn’t matter if you are self-published or with a publishing house : most of us count our blessings if we can devote 10% of our time to getting actual writing done:

A sore sight, isn’t it?

The good news is that these new waters are far from uncharted. And the best way for newbies to navigate ancient currents, is to observe what its natural inhabitants have done for generations.

While the publishing revolution might be recent, the science of business management goes back more than a century. Many pitfalls, benchmarks, do’s and don’ts have already been charted. So why waste precious time and effort on reinventing the wheel, when we’d much rather work on our next book?

This series of blogposts takes creative writers on a ride past various business management techniques, how they apply to both the writing process and the storytelling process, and why the corporate world isn’t as alien at it seems.

Don’t believe me? Let’s take a closer look.

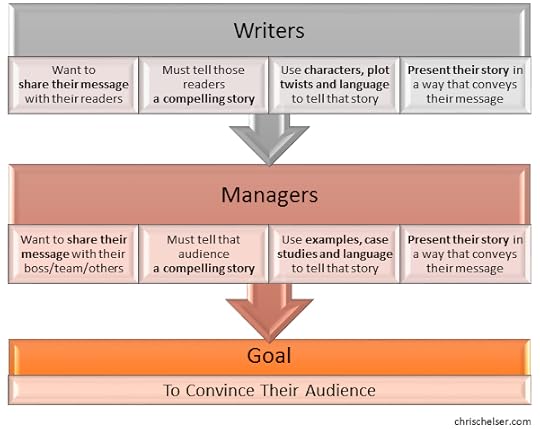

Writing Business Parallels

Society has a deep-rooted prejudice that artists are emotional and chaotic. Another prejudice says that business people are calculating and cold-hearted. Neither is true, but the human mind does so love a good stereotype. What these stereotypes neglect to mention, however, is that creative writers and business managers play the same game by very similar rules.

Creative writers and business managers play the same game by very similar rules.

Oh, don’t look so surprised. We are all human, after all. Whatever our differences in talents and temperament, we were born with a human brain that, on average, functions more or less the same as all the other human brains. For example, a sportsman’s eye-to-limb coordination is neurologically the same, regardless of whether he throws a big orange ball or a brown oblong ball.

When you break down the essence of what writers and managers do, you will find that the skills they require are equally similar. They merely play different varieties of the same game. Just look at what they do for a living:

Both writers and business managers have a day job convincing their audience.

Who that audience is and what defines “convincing” to them may differ, just like a football goal isn’t the same as a basketball hoop. But in some cases, like market-specific non-fiction books, that difference is marginal. In the end, writers and managers need to go through the same kind of motions in order to achieve the same kind of end result.

Hopefully. Like writers can produce bad fiction or rush an unpolished manuscript to print, so managers can try to launch a bad plan or rush an unfinished draft to their bosses. For both, the consequences of such mistakes are the same, too: at best you’re told off, at worst you’re laid off.

Let’s Exchange Tactics

We’re in the same game, so let’s exchange tactics.

I know from personal experience that it’s worth the effort. A significant part of my writing skills developed during my years working as a financial and legal manager, when I honed my writing tactics on court documents, official correspondence, shareholder reports and whatnot.

But there are business tactics that are much faster and easier for writers to apply: models. Schematics created to make sense of organisations, people and processes. To make complex subjects easier to understand. Models that can give authors a leg up in the writing business.

And no, they’re not swimsuit models. Still, they are worth studying in detail ;).

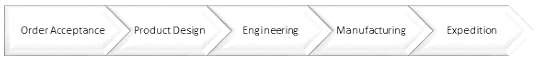

#1: Production Planning Model

Business management models don’t come any more straightforward than this one:

Don’t be deceived by its simplicity. It’s an evergreen tool for good reason: the more complex a process becomes, the more likely people are to accidentally omit a step. Spelling out every step in order helps to stay on track and make sure that all that needs to be done, is done.

Apply that to your “book production process” and you might get this:

Yes, simple. Of course you can add as many steps to it as you please, breaking down every stage into smaller steps. It is the basis for making checklists, project planning and the like.

But this model can also be used to map out essential stages in your story:

Naturally you fill in scenes and events in more detail to monitor their chronological order, keep track of whether your main character can know this particular info in that chapter or not, and if that confrontation with the Bad Guy is of more use elsewhere in the storyline.

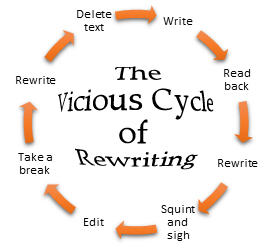

And before you dismiss this most basic model out of pride, just remember that all writers have been stuck in this other model at some point:

Many writers plan their stories and their work progress instinctively, with or without the help of sticky notes, scribbled scraps of paper or special software. Whichever your method, you are likely already using the Production Planning model.

See? Business management ideas can be useful! In Part II, we will be exploring the author’s benefits of employing two other classics from the Management Model Hall of Fame.

See you there!

Het bericht Write Like It’s Business – Part I verscheen eerst op Chris Chelser.

Photo:

Photo: