Library of Congress's Blog, page 40

September 28, 2021

National Book Festival: That’s a Wrap!

The Library’s first live event since the spring of 2020. Crossword puzzle experts Adrienne Raphel (l), Will Shortz (c) and Lulu Garcia-Navarro chat in the Coolidge Auditorium. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Let the record reflect that on Tuesday, Sept. 21, 2021, at about 7 p.m., Shari Werb, the Library’s director of the Center for Learning, Literacy and Engagement, came on stage during the National Book Festival in the Jefferson Building and said the following.

“This is the first event in our historic Coolidge Auditorium in over a year and a half.”

It was a statement so welcome and so long in coming that the crowd – most of them sitting a few seats apart around the auditorium — burst into applause. She had to wait for it to die down before adding: “And it feels really good to be back home.”

The comeback event was an on-stage, socially-distanced conversation with crossword puzzle gurus Will Shortz and Adrienne Raphel. The last event before COVID-19 shut down all live events and no small number of other Library operations? March 2, 2020. Garth Brooks, Gershwin Prize winner, chatting on the very same stage with his wife and fellow country music star Trisha Yearwood, with Librarian Carla Hayden asking the questions.

This time around, there was an even more festive atmosphere. Lulu Garcia-Navarro, host of NPR’s Weekend Edition Sunday and moderator of the event, joked when she came onstage, “I even put on my pre-pandemic jeans for the occasion.”

And then, like slipping into an comfortable pair of old shoes, the evening fell into the familiar pattern of Library events that once seemed a given: A smart, well- informed talk about an interesting subject, polite questions from a curious audience and a few laughs along the way.

As the festival wound down its 10-day schedule, with more than 100 authors appearing in a variety of platforms, Hayden was thrilled with the way the second virtual NBF had turned out.

“This year, the National Book Festival showed there is a huge appetite from booklovers across the nation to connect and engage more than ever with their favorite author,” she said. “Users were able to curate their own festival experience whether it was watching a live author conversation, listening to podcasts, streaming on-demand videos or watching the PBS special.”

The festival’s final days continued to showcase writers across the literary spectrum. There was a symposium on comic book history, “With Great Responsibility: The Spider-Man Origin Story in Art and Comic Books,” featuring the Library’s copy of the comic in which the superhero first appeared, “Amazing Fantasy” #15, from 1962. Peter Godfrey-Smith, the Australian philosopher of science, discussed how animal life developed a “sense of experience,” or consciousness, from his book “Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mind.” Novelists George Saunders (“Lincoln in the Bardo”) and Alice McDermott (“Charming Billy”) talked about their craft with Washington Post book critic Ron Charles.

And, of course, there was the perennial favorite: Cookbooks and the entertaining chefs and authors behind them.

The common refrain here is that food is never just about food. It’s about everything: family, culture, humor, shared traditions and new experiences. The blends of American cooking, which incorporates cultures and ingredients from all over the world, results in an ever-changing but always compelling menu – and conversation.

“American food wouldn’t be the same, it would be very dull without the black experience,” said Marcus Samuelsson, author of “The Rise: Black Cooks and the Soul of American Food.”

Samuelsson is head chef of the Red Rooster Harlem. He was in conversation with Hawa Hassan, the Somali-born entrepreneur who has just written, “In Bibi’s Kitchen: The Recipes and Stories of Grandmothers from the Eight African Counties that Touch the Indian Ocean.”

East African cooking isn’t widely known in the U.S., so the pair dropped into a conversation about how and where to buy the ingredients needed – specialty stores? Chain grocers? It wasn’t, they agreed, a decision just about where to find turmeric.

Hassan counseled practicality.

“If you’re starting out, I hate to endorse these bigger grocery chains, but you’re going to find cumin there, you’re going to find cardamom there,” she said. “Then, as you get more familiar with these cuisines, start going to the specialty stores to support them.”

Samuelsson agreed that would do if you were in a hurry, but there was more to the dish than just the spices.

”When you go to one of our stores, one of our markets, it’s a vibe,” he said. “It’s such a pleasure to go to an African market…it’s never is about just about buying the thing. If you’re doing that, you’re missing out. It’s about arguing about the price, it’s going back and forth, and they’re always gonna win. You know you’re going to lose, but you’re going to have a great time.”

Southern chefs brought more of a down-home flavor. The recipes and methods of cooking in the Deep South have been shaped across the generations by small-towns, home-grown vegetables, and no small amount of poverty; it’s a place where fancy ingredients aren’t on the shelves and far-flung dishes aren’t what’s on for supper.

Rodney Scott grew up in Hemingway, South Carolina, population 400, where “the biggest thing in town was your imagination.” Yearwood, the country music star, grew up in a Monticello, Georgia, population 2,000, where “our exotic spices were salt and pepper and sometimes garlic powder if we were really getting crazy.”

They both cook professionally now, though. Scott is co-founder of Rodney Scott’s Whole Hog BBQ, operating in both Charleston, South Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama. He was the 2018 recipient of the James Beard Award for Outstanding Chef Southeast and is author of “Rodney Scott’s World of BBQ: Every Day Is a Good Day.” Yearwood, author of four cookbooks (the latest is “Trisha’s Kitchen: Easy Comfort Food for Friends and Family”) hosts her own cooking show on the Food Network.

Scott cooked his first “whole hog” over an open pit at age 11; Yearwood grew up in a house where her mother cooked by ear, saying things about frying chicken like, “you cook it till it sounds right.”

Like Hassan and Samuelsson, they said that ingredients alone aren’t what makes food taste great; it’s also the life lived around its preparation.

“Food,” Scott said, “is one of the universal languages.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

September 27, 2021

Kazuo Ishiguro: People in Service, A Life of Meaning

Kazuo Ishiguro. Photo: Andrew Testa.

Nobel Laureate and Booker Prize-winning author Kazuo Ishiguro, making a headlining appearance at this year’s National Book Festival, was asked why so many of his central characters work in service-oriented jobs.

A metaphor, he said, for the lives most of us lead.

Ishiguro’s haunting works include “The Remains of the Day,” “Never Let Me Go,” and his newest, “Klara and the Sun.” In each, the central character works in service to others. In “Remains,” it’s an English butler on an estate; in “Never,” a nurse who helps coordinate organ donations; in “Klara,” a robot created in the form of a little girl to help her owners avoid loneliness and heartbreak.

Ishiguro, 66, joined the online festival from his home in London. In a conversation with Marie Arana, the Library’s former literary director, he said the “person in service” archetype – mostly arrived at unconsciously — represents people living small lives beneath the waves of history. They “torture themselves” in a struggle to be good, decent people, in the hopes that it will contribute to a larger good.

“In every endeavor, we care about this so much, and this is what fascinates me about people and it touches me about people,” he said. “It moves me about human beings, in (their) struggle to do something that they think will bring them dignity and pride and a sense of self-worth. And so I often show people in service because that is such a huge part of who we are.”

It wasn’t the only insight of the talk. In a 40-minute conversation, Arana and Ishiguro shared their stories of having a childhood in one country and an adult life in another – Arana in Peru and the U.S., Ishiguro in Japan and the United Kingdom.

He was born in Nagasaki, but moved with his parents to England when he was five. Still, his parents had not originally planned to stay long, spoke Japanese at home, and the family generally regarded England as an interesting place they were passing through. They wound up staying, but Ishiguro, while adapting fully to English life, still regarded himself as Japanese.

“I certainly don’t think as myself as an Englishman with just a few years of a Japanese childhood somewhere at the beginning,” he said. “I think the Japanese side of myself runs all the way through.

“I saw the world around me, the only one I had direct contact with, as something that was slightly provisional and certainly the values were not something that were permanent,” he continued. “…they were more the customs of the natives who we should respect and look at with interest, but these were not absolute right and wrongs about how to behave. I had one set of values at home and another at school…I think I’ve grown up with that slight distance, of dislocation.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

September 22, 2021

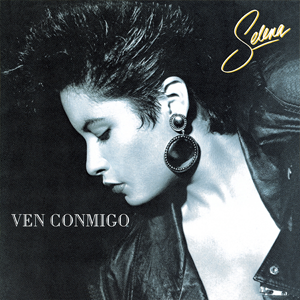

Hispanic Heritage Month: Selena’s “Ven Conmigo”

As we celebrate Hispanic Heritage Month, author Joe Nick Patoski, who has been writing about Texas music and musicians for five decades, examines Selena’s 1990 album, “Ven Conmigo.” It was added to the Library’s National Recording Registry in 2019.

To fully appreciate Selena, the superstar Tejano singer, start with “Ven Conmigo,” the second album that Selena y Los Dinos recorded for their new major label, EMI-Latin. Released in 1990, the record was a watershed for Selena and her siblings, the Quintanilla family band. They were from Corpus Christi and were serving notice that they were the new standard bearers of Tejano, the regional music popular among second- and third-generation Texans of Mexican descent.

The big band ensemble sound dated back to the 1940s and was built on the polka as its primary rhythm. Tejanos — the name also describes Texans of Mexican descent — borrowed the European dance tradition from Czech and Germans immigrants to Texas in the early 20th century and reworked it into their own style.

Tejano had its own living legend, Little Joe Hernandez of Little Joe y La Familia, but the music’s popularity had remained local until a wave of younger musicians appeared primed to reach a wider audience. Major record labels, including EMI, had taken notice and were betting on the crossover potential of acts such as Emilio Navaira, La Mafia, Grupo Mazz, and Selena.

The songs on “Ven Conmigo” illustrate the evolution that Selena and her siblings had made during nine years of management and direction from their father, Abraham Quintanilla Jr. He had once sung street-corner harmonies in his own version of Los Dinos in the early 1960s. Frustrated over his group’s inability to crossover into the mainstream, Abraham taught his English-speaking children to play the bouncy Tejano rhythm and how to sing in Spanish.

They began as a small combo that played Papa Gayo’s, the family’s Mexican restaurant in Lake Jackson, when Selena was in elementary school. Years of playing every weekend on the road polished the act into a state-of-the-art performing enterprise complete with recording studio and touring busses. Joining Selena was her older brother and producer-composer, Abraham III (known professionally as A.B. III), and her sister, Suzette, the drummer. Onstage was a full ensemble that included longtime colleague Ricky Vela on keyboards, and from Laredo, a second keyboardist, Joe Ojeda. Pete Astudillo, a singer-songwriter-dancer, co-produced with A.B. III. At the center of it all was 20-year-old Selena.

The head-and-shoulder profile photograph of Selena looking down, pensive, on the album cover, speaks volumes. The perky teen who came of age at Tejano Music Awards shows in San Antonio had grown into a woman in full flower, of exceptional natural beauty, her jet-black hair cut stylishly short.

Most songs on the album are straight up Tejano. They are distinguished by a gliding, danceable rhythm with keyboards and synthesizers replacing the traditional accordion and horns for a more modern sound. Then there were the romantic ballads, showcasing Selena’s soaring vocals.

That strange, weird polka groove drives the title track, with David Lee Garza’s accordion added on this song for old-school street cred. It also distinguishes “Yo Te Amo,” a duet Selena sings with Astudillo, on a song he co-wrote. The updated polkita rhythm also defines “La Tracalera,” a much-improved remake of her 1982 version of the Tex-Mex truckers’ anthem, complete with shout outs to San Antonio, Laredo, Houston, Dallas, Waco, Victoria, Corpus Christi, and La Feria.

“La Tracalera,” “Aunque No Salga El Sol” and “Despues de Enero” — the last a ballad showcasing Selena’s vocal range — were written by Johnny Herrera, her father’s mentor. Herrera, from Corpus Christi, had several hits in Mexico in the 1950s where he was known as “El Suspiro,” the Sigh.

Three songs on “Ven Conmigo” offer hints where Selena was headed.

The second single, “Baila Esta Cumbia,” completely strayed from the Tejano formula. The song was a cumbia, not a polka, and was produced by Astudillo and A.B. III. It borrowed heavily from Fito Olivares, who hailed from the Texas-Mexico borderlands. Powered by a mesmerizing beat tailored for dancing, the song hit big in Mexico, something few Tejano bands had accomplished. Selena was opening doors.

“Enamorada de Ti,” another percussive, made-for-dance collaboration between A.B. III and Astudillo, features a rap break with a growling, assertive Selena busting rhymes, showing what she’s got.

Along with “No Quiero Saber,” the production team was making a strong case that they could create the English-language crossover songs that the label executives wanted when they signed Selena.

“Ven Conmigo” froze all that in time.

Weeks after the album’s release, guitarist Chris Perez joined Los Dinos, adding a rock component to the band’s sound. Two years later, he and Selena married.

With “Ven Conmigo,” Selena was ascendant, earning comparisons to Gloria Estefan and Madonna. She was signed to endorse Coca-Cola, the first Tejana to do so. Yet to come were concerts that filled Houston’s Astrodome with 60,000 fans; street dances at Miami’s Calle Ocho that turned on the larger Latin music world to this new singer coming out of Texas; a movie with Johnny Depp; and a role in a Mexican telenovela. Each album that followed topped the previous one, capped by 1994’s fully-formed “Amor Prohibido,” which sold more than 500,000 copies. It was only the second time a Tejano act had sold that many records.

The success of “Ven Conmigo” also attracted the attention of Yolanda Saldivar, a San Antonio nurse. She first asked to run Selena’s fan club, but eventually worked her way into being Selena’s business associate, managing the singer’s boutique in San Antonio and assisting Selena as she developed a fashion line with designer Martin Gomez.

On the morning of March 31, 1995, Saldivar shot Selena to death at a Corpus Christi motel, following a dispute over charges that Saldivar had been embezzling funds. She was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. She is eligible for parole in 2025.

Selena’s legacy, meanwhile, glows brighter than ever.

Joe Nick Patoski has authored and co-authored biographies of Willie Nelson, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Selena, and the Dallas Cowboys.

September 21, 2021

Jason Reynolds Takes a Third Lap

As the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature for the past two years, Jason Reynolds has been an enthusiastic and supportive proponent of reading, writing and creativity, even in the depth of the pandemic. In April 2020, we joined with him to launch a 30-part video series for kids, “Write. Right. Rite,” offering fun and engaging prompts to express creativity. The popular video shorts were widely used in home and classroom settings during a time when social distancing required fresh and engaging virtual content.

“Jason’s GRAB THE MIC platform has proven that connecting with kids on their level empowers real world growth in reading and writing,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. Today, she made it official: Reynolds has been appointed to an unprecedented third year as National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. The Ambassador program is an initiative of the Library in partnership with Every Child a Reader and the Children’s Book Council, with generous support from Dollar General Literacy Foundation.

Reynolds discussed plans for his third year during an interview on NPR’s TED Radio Hour podcast at the Library of Congress National Book Festival. You can also read the complete announcement on his third year, with details of those plans, which include a nationwide virtual tour to meet students in rural communities to continue his work of encouraging young people to share their own narratives and write their stories.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

September 17, 2021

Welcome to the 2021 National Book Festival!

The 2021 Library of Congress National Book Festival has begun! Watch as News4 Today journalist Eun Yang talks to Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden about this year’s Festival:

{mediaObjectId:'CC21D5071FA79A90E053CAE7938CDE48',playerSize:'mediumWide'}Join us for the 2021 National Book Festival, Sept. 17-26. Audiences are invited to create their own festival experience this year, with more than 100 authors in programs in a range of formats. Subscribe to the Festival blog for future updates, and visit the Festival website.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

September 16, 2021

Medieval Manuscripts in the Digital Age

Detail from the “Book of Hours.” published in France, circa 1420. Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

This is a guest post by Marianna Stell, a reference assistant in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. It appeared earlier this year in the Library of Congress Magazine.

Like contemporary digital interfaces, medieval manuscripts anticipate an engaged user. Imagine that you are viewing a well-designed webpage from behind the glass of a museum case. The glass would prevent you from interacting with the page as the designer intended. You would be an observer, not a user.

Viewing a medieval manuscript without information about its historical context can be a similarly limited experience. Medieval manuscripts are not static products. Like a website, a manuscript realizes its purpose in its dynamic engagement with its user. Rather than simply instructing readers, a manuscript’s compositional program is designed to move viewers to some action. The nature of the action depends upon the context for which the manuscript was created to function.

An illuminated prayer book, like the one by the Boucicault Master pictured above, is designed to catch the user’s attention. Light dances off the many flecks of gold leaf used in the borders and the miniatures, catching the eye of the reader with even the smallest motion and making the page appear as though it is illumined from within. Books of Hours like this one were created to allow laypersons to participate in the cycle of prayers that priests and monastic orders kept. The program of images and words connected domestic habits to the larger rhythms of the church festival calendar and the cycle of the seasons.

Intended to be portable, Books of Hours were sometimes fashioned as a girdle book. The length of cloth attached to the binding was tied in a knot and often tucked into a belt for easy transport. As a consequence, Books of Hours were used at home, at church and even at gravesides.

Not all medieval manuscripts were created for a ritual context, however. Some manuscripts were created to prompt mental rather than physical engagement. Manuscripts created for personal study assumed use in the active theater of the reader’s mind. A 15th-century encyclopedic manuscript in the Rosenwald Collection contains compositions that are built to generate mental associations. The design is a testament to the medieval creator’s ability to nest layers of information into a central image so that the reader might more easily remember the content.

This medieval manuscript references a metaphor that scholars ride on the shoulders of their mightier predecessors. Germany, circa 1410. Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

A 15th-century reader would recognize an image of what looks to be a piggyback ride as referring to a famous metaphor attributed to Bernard of Chartres, who claimed that modern scholars (i.e., those working around 1150 A.D.) are like dwarves being carried by giants. The modern scholar can see further into the horizon only because the ancients, like the giant, have given him a leg up. Modern knowledge therefore rests in a privileged position only because of those giants who wrote and studied beforehand. Illustrating this point, the giant’s surcoat (what we’d call an overcoat today) is inscribed with references to the seven liberal arts, which the medieval educational system inherited from the Romans.

The design of the composition moves the reader around in a circle, like the one labeled “macrocosm” above the head of the dwarf. By following the internal itinerary of the page, the reader actively experiences and internalizes its informational content. In so doing the reader becomes part of the manuscript’s larger message: Each human being is a microcosm of the greater macrocosm of the universe.

For those of us studying book arts in the digital age, we are the dwarves and the medieval manuscript designers are our giants.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

September 14, 2021

Maps: The (Bright) Side of the Moon

The 1962 map of the moon. The Sea of Tranquility, where the Apollo 11 mission landed, is the large dark area at center right, Geography and Map Division.

Cynthia Smith, a reference specialist in the Geography and Map Division, wrote a short piece about this lunar map for the Library of Congress Magazine. It’s been expanded here.

The Soviet Union demonstrated its early lead in the Cold War space race with the United States with the launch of the satellite Sputnik 1 in 1957. They continued to develop their space program and, in April 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth.

The orbit was a dicey proposition. Nearly half of Soviet rocket launches had failed. A launch pad explosion in 1960 had killed dozens of people, perhaps more than 1o0. Somehow, Gagarin was preternaturally calm on April 12, the morning of his launch. His pulse rate was just 64 a few minutes before liftoff. Then the rockets kicked in on Vostok 1, his ship, sending him just beyond the Earth’s atmosphere.

His single orbit took just under two hours. It was not a good ride. He thought he was going to burn to death during reentry. He could seem flames licking the outside of his ship. “I’m burning,” he told ground control. “Goodbye, comrades.”

The flames were just burning plasma, though. Gagarin’s capsule spun wildly, the result of coming in too fast, nearly causing him to black out. But he managed to eject from the capsule, as planned, at about 23,000 feet, still in his space suit, and land safely in a field in the Saratov Oblast, near the Volga River.

He instantly became a Soviet hero and an international celebrity.

Nowhere outside of the Soviet Union did his name resonate more than in the United States, where space flight was in its infancy. So galling was Gagarin’s success that President John F. Kennedy went before a joint session of Congress a month later, laying out an astonishing goal: The U.S. would put astronauts on the moon by the end of the decade, he said.

That speech set off one of the most ambitious American scientific projects of the 20th century. Early on, the mission needed a detailed map of the moon, to see where this proposed flight might land. To that end, the Aeronautical Chart and Information Center of the U.S. Air Force compiled the above lunar photo mosaic map in November 1962, using remote sensing imagery. Scientists and photographers had drawn and photographed the moon, dating back to the 17th century. But this was a project that needed a cartographer’s scientific skillset, as the National Geo Spatial–Intelligence Agency (the ACIC’s descendant) points out in a post about their work on the mission.

“Accurate coordinates of the sites needed to be determined in a coordinate system consistent with accurate vehicle orbit information,” said John Unruh, a former ACIC cartographer and scientist. The agency would go on to create hundreds of maps for the Apollo missions, including 3-D plastic models of the moon’s surface at proposed landing sites.

The following years were dangerous ones for both nation’s space programs.

On Jan. 27, 1967, three U.S. astronauts — Gus Grissom, Edward White II and Roger B. Chaffee — were killed when their Apollo 1 capsule caught fire during a training exercise at Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Three months later, Soviet cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov was killed during an orbiting mission in a very flawed spaceship. His capsule hurtled back to Earth, its parachutes failing to open, killing him on impact. Intercepted radio communications showed that, as the module fell, he was screaming in rage at Soviet space officials for sending him on a doomed mission. Then, on March 27, 1968, Gagarin himself was killed in a training jet exercise.

The Apollo 11 Command Module. Photo: Smithsonian Institution.

Still, less than 16 months later, on July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to land on the moon — an achievement once considered impossible and a demonstration of the United States’ now commanding lead in the space race. The landing module was put down in the Sea of Tranquility, a flat plain of dark lava that is roughly 700 kilometers in diameter. You can see it on the map above, just to the right of the middle center, as a broad, darker section that extends at a downward angle. It is to the left of the large round crater at center right.

It was there, with the help of a map made 238,900 miles away, that Armstrong took his “one small step” that was a “giant leap” for mankind.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

September 9, 2021

Venture Smith: The First Slave Narrative

Descendants of Venture Smith gather at his gravesite in East Haddam, Connecticut, during the town’s 2019 Venture Smith Day. Photo courtesy of Venture Smith Day Celebration Committee.

Delighted to write this post with Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“I was born at Dukandarra, in Guinea, about the year 1729. My father’s name was Saungin Furro, Prince of the tribe of Dukandarra.”

That’s the opening line of Venture Smith’s “A Narrative of The Life And Adventures of Venture, A Native Of Africa: But Resident Above Sixty Years in the United States of America,” the earliest slave narrative in the United States, published in 1798.

The Library has an original copy of the 32-page pamphlet, preserved in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Publishing by the Charles Holt company, it is still in print 223 years after publication (you can also read it online for free) and is the basis for biographies of Smith and academic studies of the era.

Smith’s narrative is a rare account of slavery in Colonial New England, one of only a few ever published. It’s also one of the very few records of enslaved people who told of their lives in Africa, among them the handwritten autobiography of Omar ibn Said, also preserved at the Library.

Today, the city of East Haddam, Connecticut, near the farm where Smith settled for the last decades of his life after buying his freedom, lists his gravesite as a tourist attraction and will celebrate the 25th annual Venture Smith Day this Saturday, Sept. 11. In 2006-07, archaeologists excavated his long-lost homestead and published a fascinating pamphlet, “The Venture Smith Homestead.” (The site is now part of the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge and is not open to the public.)

“(The homestead) wasn’t quite in the place people thought it had been,” said Lucianne Lavin, the lead archaeologist on the project. “It was completely grown over, with only a few stone ruins. You’d never have known there had been three houses, a huge storage building, a barn.”

Smith’s story is a harrowing tale, filled with kidnappings, fistfights, years of hard labor and, finally, love and perseverance. Smith was 70, bent with age and nearly blind at the time he told his story, but he owned more than 130 acres of land, a waterfront compound on the Salmon River that included three houses, a dry dock, blacksmith shop and several warehouses. He was still married to his wife, Meg, whom he had worked for eight years to buy out of enslavement.

The title page of Venture Smith’s life story. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“It gives me joy to think that I have and that I deserve so good a character, especially for truth and integrity,” he says near the end of his story (emphasis in the original).

The pamphlet was clearly intended as a rebuke to slavery, but the editor’s preface contains passages that are startling to modern sensibilities. Smith grew up “wholly destitute of all education but what he received in common with other domesticated animals,” they write. Still, the editors note his intelligence, drive and ambition. They tartly observe that “perhaps some white people would not find themselves degraded by imitating such an example.”

Smith’s story begins on the west African savanna, a couple of hundred miles inland. His real name was Broteer Furro and he was the son of a prince of Dukandarra (scholars have not been able to locate the place; it may have been a small kingdom that disappeared long ago).

Though privileged, his early life was traumatic. His mother fled with the children after an argument with his father, running into the wilderness. Broteer was perhaps 4 years old, as he recalled. She eventually left him with a kind farmer while she continued on with his siblings. He did not hear from his family again for more than a year, until his father sent for him after reconciling with his mother.

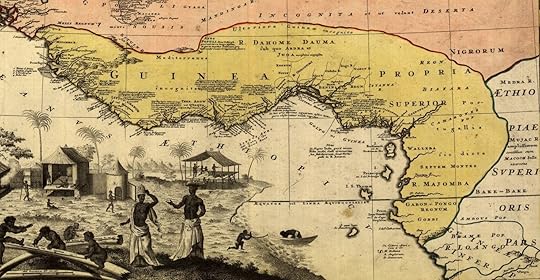

This 1743 map highlights the western savanna region of Africa. The map was made with Venture Smith was about 4 years old. Map: Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’ Anville. Geography and Map Division.

But shortly after his return, an army from a neighboring region rampaged through their village. His father was tortured to death in front of his family. “The shocking scene is to this day fresh in my mind, and I have often been overcome while thinking on it,” he dictated more than six decades later.

Broteer, his mother, siblings and hundreds of others were bound together and marched hundreds of miles to the coast. He does not say what became of his mother and siblings, but he was sold on the coast of modern-day Ghana, along with about 260 others, to the owner of a Rhode Island slave ship.

The ship’s captain paid “four gallons of rum and a piece of calico cloth” for the child and told him his new name was “Venture.” (Decades later, he would take the surname of his last owner, Oliver Smith.) The ship was likely the Charming Susannah, which departed Newport in late 1738 and returned in September 1739, according to Connecticut Humanities, a nonprofit division of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The Middle Passage voyage was brutal; a quarter of the enslaved died of a smallpox outbreak. Most of the survivors were sold in Barbados, but a handful were brought to Rhode Island. Smith, then about 6 years old, was bought by George Mumford, a commercial farmer. He was soon assigned to carding wool and grinding corn, often subjected to physical abuse.

He grew into a tall, powerful man, often described as weighing more than 300 pounds, and so renowned for his feats of strength that he was later remembered as the “black Paul Bunyan.” In his early 20s, he married Meg, an enslaved young woman who worked for the same owner. For the next decade, he labored for one owner or another, fishing, working on ships in the bay, or chopping hundreds of cords of firewood.

He recounted several fights with his owners, trading punches and once being clubbed on the back of the head with a log. In April 1754, he and several others made a short-lived escape. Realizing they were going to be caught, he returned on his own, but not before his owner placed a runaway slave ad. It is the only known contemporary description of him, according to Connecticut Humanities: “… he is a very tall Fellow, 6 feet 2 Inches high, thick square Shoulders, Large bon’d, mark’d in the Face, or scar’d with a Knife in his own Country.”

The final chapter describes Smith’s life after he bought his freedom, at age 36. “My freedom is a privilege which nothing else can equal,” he wrote.

Venture Smith’s farm was along the waterfront near the intersection of the Salmon river. Map by Carrington Bowles, ca 1780. Geography and Map Division.

He worked for four years to buy the freedom of his sons, Cuff and Solomon, and then another four years to buy Meg’s freedom. They both then worked to buy the freedom of Hannah, their daughter.

Historians note there is little in the record that shows what his life was like as a free man, and that his autobiography includes almost nothing about his wife and children save their names and when two of them died.

But it is clear that he was a well-established figure in the community, said Lavin, the archaeologist. His farm and houses, she notes, was not a typical enterprise by European settlers, but more akin to a west African family compound. His sons and their families lived in the two other houses on the property (his daughter died as a young adult) and they were almost entirely self-sufficient. His sailed on Connecticut and Salmon rivers, hauling cargo, trading goods and repairing boats. He farmed and sold lumber that he had cut. He bought freedom for at least three other enslaved men. Perhaps the best measure of how well he was regarded, historians say, is the existence of his autobiography and that he was buried in a prominent place in the local church cemetery, even though he was not a member of the congregation.

But it was never an easy life. He never learned to read and write very well and was often conned by whites who could. A wealthy businessman once falsely accused him of losing a barrel of molasses in shipment, sued him for it and then “insultingly taunted” him about it.

“But Captain Hart was a white gentleman, and I a poor African, and therefore it was all right, and good enough for the black dog,” he wrote.

That’s the voice that still commands attention, centuries later — a proud, defiant man, forging his way on a vast, often cruel continent.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

September 8, 2021

20 Years Ago Today: Remembering the First National Book Festival

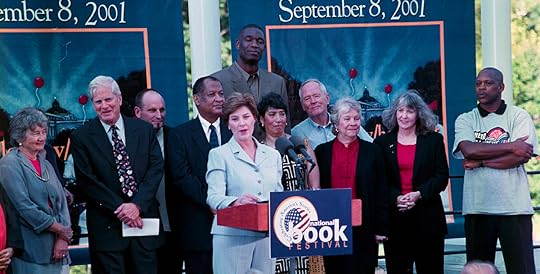

Laura Bush (center), Dr. James Billington and others open the first National Book Festival Sept. 8, 2001 outside the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Photo by Yusef El-Amin

It was a beautiful, sunny Saturday morning on Sept. 8, 2001. I was one of hundreds of excited Library of Congress employees and volunteers getting ready to host the very first Library of Congress National Book Festival here in Washington.

This was before the Festival was a vast tent city on the National Mall (2002-2013) or a huge, expo-style event in the Washington Convention Center (2014-2019) – and certainly before it was the virtual event that we’ve seen in the past two years, compelled by the COVID pandemic. Back then, it was a totally new idea, envisioned by first lady Laura Bush, who founded the Texas Book Festival when she was first lady of that state. She suggested a national festival to then-Librarian of Congress James Billington at a reception at the Library the night before George W. Bush was to inaugurated as 43th U.S. president in a ceremony to be held just across the street.

A national book festival was a big idea and would be a big undertaking. We didn’t even have social media to talk about it back then. We advertised this new Festival the old-fashioned way: newspaper ads, announcements to TV, radio and other media, and good old word-of-mouth. Working as part the team responsible for publicity, I was frankly a little anxious as we approached our starting time. Would people show up?

Boy, did they ever. Thousands were on hand as Dr. Billington and Mrs. Bush formally opened the Festival at 9:30 a.m. (She went on to serve as the National Book Festival’s honorary chair through 2008.) “We’ve come together to revel in the joy of the written word,” she said to a big, cheerful crowd.

What a day it was! Some 30,000 book lovers of all ages crowded the halls of the Library’s Capitol Hill buildings and tents set up on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol to hear 60 of their favorite authors, visit with players from the NBA, listen to Library curators and hang out with Clifford the Big Red Dog. Writers signed books and posters, answered questions, and bumped elbows with their fans.

Streets around the Capitol and the Library were cordoned off, and it all felt like a small-town fair. I remember being on the plaza outside the James Madison Memorial Building, which had become a makeshift open-air dining area with a few food trucks. There I was, munching on a hot dog, when Mrs. Bush strolled by, casually checking in to chat with surprised festival-goers and enjoying the day just about as much as anyone.

Here’s a story from our Library of Congress Information Bulletin with more details about our first Festival. And here is a selection of author talks from that day.

Three days later, on September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks changed the world – and the Capitol Hill campus of the Library of Congress was not immune to those changes. Since that sunny, happy day, there have been lots of changes in the way we get around in Washington and on the Library’s campus, as well as changes to the National Book Festival through the years.

But none of these changes have kept the Library and our Festival sponsors from celebrating books, authors, poets and the love of reading with a nationwide audience every year. It’s been my great joy to have worked on every National Book Festival since it started. I may be biased, but I think this year’s will be the best one yet.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Author Liz Carpenter, who was Lady Bird Johnson’s press secretary and chief of staff during the Johnson administration, captivated a crowd in one of the author tents set up on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol. Photo by Christina Tyler Wenks

Library Announces Winners of 2021 Literacy Awards

On this International Literacy Day, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden has announced that three organizations working to expand literacy and promote reading are the 2021 recipients of the Library of Congress Literacy Awards. The awards honor organizations doing exemplary, innovative and replicable work and recognize the need for the international community to unite in achieving universal literacy.

“Literacy develops the mind and the heart, engages the intellect and imagination, and builds wide-ranging knowledge of the world,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “Through the generosity of David M. Rubenstein, the Library of Congress is proud to honor and celebrate the achievements of these extraordinary organizations in their efforts to advance literacy and enable people to survive and thrive in the world.” This year’s recipients:

2021 David M. Rubenstein Prize ($150,000): Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library, Pigeon Forge, TennesseeThe Imagination Library, also known as Dolly’s Library, is an initiative of the Dollywood Foundation, a nonprofit organization founded by Dolly Parton in 1988. Dedicated to improving the lives of children by inspiring a love of reading, the Imagination Library provides books free of charge to families through local community partnerships.American Prize ($50,000): The Parents as Teachers National Center, St. Louis, Missouri

Parents as Teachers builds strong communities, thriving families, and children who are healthy, safe and ready to learn by matching parents and caregivers with trained professionals who make regular personal home visits during a child’s earliest years in life, from prenatal through kindergarten. Parents as Teachers (PAT) began in the 1980s and is now the most replicated home visiting model in the United States.International Prize ($50,000): The Luminos Fund, Boston, Massachusetts

The Luminos Fund provides transformative education programs to thousands of out-of-school children, helping them to catch up to grade level, reintegrate into local schools and prepare for lifelong learning. It delivers a joyful-learning approach in classrooms in Ethiopia, Liberia and Lebanon to help children cover three school grades of learning in 10 months.

The Library of Congress Literacy Awards Program also honored an 14 additional organizations for their implementation of highly successful practices in literacy promotion. For more details, see the complete announcement or visit the Literacy Awards website.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers