Library of Congress's Blog, page 41

September 1, 2021

Library Legend John Y. Cole Retires

John Y. Cole stands before a portrait of Ainsworth Rand Spofford, his favorite Librarian of Congress. Photo by Shealah Craighead.

John Y. Cole is the historian of the Library of Congress and the former director of the Library’s Center for the Book. He began working at the Library in 1966 and is retiring this month.

Where did you grow up and go to school?

I was born and raised in Washington state, graduating from the University of Washington with degrees in history and librarianship. My grandfather was an itinerant linotype operator and newspaper editor who read to me frequently, managing to instill both printer’s ink and a love of reading in his grandson.

What first drew you to library work and ultimately to the Library?

At the University of Washington I was “lured” into library school by a wonderful teacher who introduced me to book and library history. My next lucky break came in 1964, when my two-year ROTC obligation took me to the U.S. Army Intelligence School at Fort Holabird near Baltimore, where fortunately my graduate library school degree was noticed.

As a result, and without my knowledge, 2nd Lt. Cole was not assigned to Vietnam with most of the rest of his class, but instead “stayed home” to head the Intelligence School Library. I learned about the Library of Congress (loved it from the start!) when I began visiting the Library’s Surplus Duplicate Collection to gather materials for my U.S. Army Intelligence School Library.

How did your career at the Library evolve?

I left the Army in 1966, knocked on the door of the Library’s Personnel Office and was shepherded into the 1966-67 professional intern program, then called special recruits. I served as the Library’s adviser for the program for the next several years; an early career satisfaction was being able to facilitate the opening up of this valuable “outsider” experience to qualified Library employees.

I soon found a job in the Collections Development Office in the Reference Department, which was a good “Library-wide” fit with my recent part-time enrollment in the American Studies Ph.D. program at George Washington University. My dissertation topic focused on Ainsworth Rand Spofford, Librarian of Congress 1864-1897.

My interest in Library history was one of the reasons that, in 1976, Librarian of Congress Daniel J. Boorstin asked me to chair his one-year task force on goals, organization and planning. This key experience led in 1977 to my appointment as the first (and at the time the only) staff member of the newly created Center for the Book.

What inspires you to study and write about the Library’s history?

During my initial training year at the Library, I read “The Story Up to Now: The Library of Congress 1800-1946,” by David C. Mearns, a distinguished Library veteran who joined the staff in 1918 and retired in 1967 — one year after I had arrived.

I was astonished to learn about the national library vision and accomplishments of Spofford, who then was a relatively unknown Librarian of Congress. Mearns encouraged me to take Spofford on as a dissertation topic. I did so and then followed up on a lead from an earlier issue of the Library’s Information Bulletin about Spofford descendants in the D.C. area. To my amazement and delight, these family members in Great Falls, Virginia, and also New York City had kept important Spofford manuscripts and documents as well as a color portrait — all eventually donated to the Library. I still am inspired by Spofford and his remarkable achievements.

What are a couple of standout memories from your career?

Overall, I’m grateful to have been able to contribute to the Library in several different ways, especially in helping increasing understanding of our unusual and somewhat complicated role in American government and culture.

Specifically, I was privileged through my 39 years of service as the founding director of the Center for the Book to work closely with Librarians of Congress Daniel J. Boorstin and James H. Billington — both strong personalities who also loved the Library.

I especially treasure the friendships I developed, in tandem with Dr. Billington, with first ladies Barbara Bush, the honorary chair of Center for the Book national reading promotion campaigns from 1989 to 1992, and in 2001 with Laura Bush, the “founder” and co-chair, with Dr. Billington, of the National Book Festival.

What’s a little-known fun fact you’ve uncovered about the Library?

In January 1898, “on behalf of the American home,” the National Women’s Christian Temperance Union urged “our National Library” to stop liquor sales in its restaurant on the third floor of the newly opened Jefferson Building. And the campaign apparently was successful.

What do you see as the most significant changes at the Library during your time here?

The continued expansion and improvement of the institution, thanks largely to better internal communication with the staff and with also with Congress, libraries, scholars and researchers, and the general public.

Concurrently, a growing awareness of the Library’s unique characteristics on the part of both its staff and its talented top leadership. Each of the Librarians of Congress “during my time” has brought different interests and talents to the institution, continuing the “balance” needed to continue a high standard of service to our wide range of constituents — local, national and international.

What will you do during retirement?

My wife, Nancy Gwinn, retired last year after a long career at the Smithsonian Libraries. Now that I’m finally (in her view) joining her ranks, we will have more time, especially for family and international travel. The D.C. area, however, will remain our home, with our condo in Arizona as a western outpost. And of course I’ll be working on an interesting Library history project or two wherever I am!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

August 30, 2021

The 2021 National Book Festival: Big Names, Great Books, Stellar Conversations

Nobel Laureate Kazuo Ishiguro. Photo: Andrew Testa.

No matter what kind of books and authors you love, the Library’s 2021 National Book Festival has a star-studded cast that you can watch – and chat with – in a 10-day series of events starting Sept. 17.

Nobel laureate Kazuo Ishiguro, who has dazzled us over the years with “Remains of the Day” and “Never Let Me Go,” will be online to talk about his new book, “Klara and the Sun.” Joy Williams, the 2021 recipient of the Library’s Prize for American Fiction, debuts her new novel, “Harrow,” the week of the festival. Film stars Lupita Nyong’o and Michael J. Fox will be on hand to talk about their latest books, as will fashion icon Diane von Furstenberg. The New Yorker’s Patrick Radden Keefe, whose “Say Nothing” was a riveting account of Northern Ireland’s political violence, is here with his new bestseller, “Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty.”

In all, the festival will feature more than 100 authors, poets and writers in a range of formats under the theme of “Open a Book, Open the World.” The virtual programs will roll out over 10 days from Sept. 17-26.

Lupita Nyong’o. Photo:: Nick Barose.

Not sure what you want to see? You can get an hour-long preview of the festival with guest host LeVar Burton and Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden in a PBS special on Sept. 14 (check local listings). The pair will be back to kick off the festival in a live conversation on Sept. 17 at 7 p.m. ET.

Almost everything is online again this year, due to COVID-19 concerns, and will range from videos on demand to author conversations in real time and live question-and-answer sessions. Live events will also be recorded for viewing on demand, so you can check them out later. In addition to the schedule, linked to above, there’s the National Book Festival blog to keep you up to date with developments. You can also sign up for updates.

There’s the usual array of powerhouse writers, ranging from literary fiction, history and biography, science, lifestyle, teens and children, poetry and so on. Pulitzer Prize-winning historians Annette Gordon-Reed and Kai Bird will be here, as will organizational psychologist Adam Grant, whose bestselling books “Originals” and “Think Again” have challenged the way we think about…well, thinking.

Somalia-born model and food entrepreneur Hawa Hassan will talk about how she got her Basbaas Foods business going, along with her cookbook, “In Bibi’s Kitchen.” Also on the kitchen front, Trisha Yearwood will take a break from her singing career (a mere 15 million albums sold) to talk up her new cookbook, “Trisha’s Kitchen.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen. Photo: BeBe Jacobs.

In Young Adult fiction, Angie Thomas, latest in a long line of Mississippi authors, comes to us with “Concrete Rose,” a prequel to her debut bestseller, “The Hate U Give.” There’s also Traci Chee, of the Reader Trilogy fame, and, of course, Jason Reynolds, the Library’s National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, will be here, too.

In fiction, it’s just crazy. In addition to Ishiguro and Williams, there’s Tana French, Roxane Gay, Yaa Gyasi, Elliot Ackerman, Alice McDermott, Viet Thanh Nguyen and George Saunders, among more than a dozen others.

For those of you in the D.C. area, there are a pair of live conversations scheduled. Crossword puzzle lovers will get a kick out of a Sept. 21 evening talk with maestros Adrienne Raphel and Will Shortz. Raphel is author of “Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them,” and Shortz is the longtime New York Times crossword puzzle editor.

The second event, Sept. 25, is Nikki Giovanni, the legendary poet and author, in conversation with Hayden. Chief on her mind will be her new book, “Make Me Rain: Poems & Prose.” The setting for both is still being determined, again due to the ongoing COVID-19 situation.

Be sure to bookmark the festival blog and website. See you there!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

The poster for 2021 National Book Festival. Artist: Dana Tanamachi.

August 25, 2021

The Islamic World Map of 1154

The world map of al-Idrisi in 1154. It’s upside down from the modern point of view — the south at the top, north at the bottom — and Mecca at the center top. Facsimile by Konrad Miller, 1928. Geography and Map Division.

This is a guest post by Sundeep Mahendra, head of the Research Access and Collection Development Section in the Geography and Map Division.

Early in the 12th century, King Roger II of Sicily commissioned Arab Muslim geographer and cartographer Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Abdallah ibn Idrīs al-sharif al-Idrīsī (or al-Idrisi) to produce a book detailing the geography of the known world.

Over the course of nine years, and drawing on earlier works by Ptolemy, Arabic sources, firsthand information from world travelers and his own experience, al-Idrisi in 1154 completed what became one of the most detailed geographical works created during the medieval period.

Consisting of 70 separate section maps with accompanying text, when put together the original sheets would have created a rectangular map 9 feet, 5 inches long. In 1928, Konrad Miller produced this re-creation of al-Idrisi’s original work.

To a modern viewer acclimated to north being placed at the top of a map, this view of the world may seem skewed or even upside down. However, orienting maps with the south at the top was a common practice in Islamic cartography. Viewed from this direction, Mecca, the most holy city in the Islamic world and its focal point, is at the top and most prominent section of the map.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

August 23, 2021

Back to School: Abe Lincoln’s Grammar Book

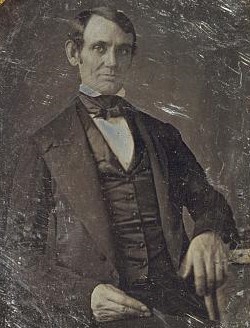

This 1846 or 1847 daguerreotype is the earliest known photograph of Abraham Lincoln. He was 37 and a Congressman-elect from Illinois. Photo: Nicholas H. Shepherd. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Abraham Lincoln never really had a “back to school” moment, as the future president was raised on a farm and had less than a year of formal schooling. This didn’t mean he didn’t love learning, though. From an early age, he devoted intense effort to self-study through reading.

In 1831, when he was 22, Lincoln left his frontier home in southwestern Illinois for the bustling village of New Salem, Illinois. Over the next few years, he worked as a store clerk, dabbled in business, served as postmaster and engaged in a serious regimen of self-education. By today’s standards, he was old enough to be a college graduate, but still considered his education to be “defective.”

So, soon after arriving in New Salem, Lincoln contacted the local schoolmaster, Mentor Graham, about the availability of a proper grammar for his study. Graham apparently recommended Samuel Kirkham’s 1828 volume, “English Grammar in Familiar Lectures.”

This was an influential, all-in-one volume that went through many editions over the years. It was filled with rules of grammar and syntax, sentence structure, instructions on pronunciation and basic composition, as well as warnings against provincialisms, such as “ain’t” “izzent,” and “askst.” There was a guide to common but erroneous manners of speech (“Give me them there books”) paired with the the correct way (“Give me those books.”)

Lincoln’s copy of Kirkham’s “English Grammar.” Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

“This work is mainly designed as a Reading-Book for Schools,” the introduction read. “In the part of it, the principles of reading are developed and explained in a scientific and practical manner, and so familiarly illustrated in their application to practical examples as to enable even the juvenile mind very readily to comprehend their nature and character, their design and use, and thus to acquire that high degree of excellence, both, in reading and speaking, which all desire, but to which few attain.” (emphasis in the original.)

Lincoln definitely wanted to attain that “high degree of excellence.” When it turned out that the only available copy of “Grammar” in the area was at the farm of John Vance, some six miles out of town, Lincoln didn’t hesitate. After the 12-mile round trip, and a few chores to help him earn the book, Lincoln returned home with his prized possession. It is the earliest book known to have been in Lincoln’s possession and is now in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

It was noted that Lincoln always had the book with him. He would later remark that it was his study of grammar that shaped his success and later gave voice to his eloquent speeches. Most likely he had it in hand one day when he acted on behalf of Denton Offutt, the owner of the general store at which he clerked. He was handling a receipt between James Rutledge and David Nelson. Today, that receipt is still attached to the inside front cover of the book.

Lincoln’s signature on the Offutt receipt. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

It was while working at Offutt’s store that Lincoln is said to have accidentally overcharged a customer. At Offutt’s insistence, Lincoln traveled the many miles to make amends for the error, earning him the sobriquet “Honest Abe.”

Meanwhile, that receipt is of more than just passing interest. The first party of the receipt, Rutledge, owned the local tavern, and his daughter, Anne, stayed with him. One version of this story, most likely apocryphal, is that Abe first became well acquainted with Anne in 1833 at her father’s tavern. Although she was engaged, the long absence of her intended freed Anne to eventually fall in love with young mister Lincoln. A promise was made to marry once she was released from her commitment.

Whatever the actual circumstances, they were on such good terms that Abe wrote on the title page: “Anne M. Rutledge is now learning grammar.” Whether this was a sweet double entendre between two young lovers, or just a polite inscription between friends, remains a matter of conjecture.

But more was not to come. Typhoid fever swept through New Salem in the late summer of 1835. Anne died of complications of the disease on August 25 — 186 years ago this week. Lincoln is said to have slid into a deep, dark depression. He eventually recovered, went on to work as a lawyer, and eventually married Mary Todd Lincoln seven years later.

The lessons he learned from Kirkham’s “English Grammar” stayed with him and helped him give the nation some of the most memorable speeches in its history.

Lincoln wrote “Anne M. Rutledge is now learning grammar” on the title page of his copy of Kelsey’s “Grammar.” Rare Book and Special Collections division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

August 19, 2021

Summer Beauties: The Golden Age of Travel Posters

This Depression-era Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project poster urged Americans to travel. Artist: Alexander Dux. Prints and Photographs Division.

Jan Grenci, a reference specialist in the Prints & Photographs Division, wrote a short piece about travel posters in the July/August issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. It’s been expanded here.

Some of the Library’s most popular Free to Use and Reuse photographs and prints are the travel posters from the golden age of the art form, the 1920s to the 1960s, when artists used graphic design, bold lines and deep colors to render destinations more as a mood than just a place.

Take, for example, that image above. The massive scale of the stalagmites and stalactites, the huge cavern opening — they combine to dwarf the man and woman in the foreground. The blueish/purple geologic formations, lit softly from the right, are offset by the shadows in deep black. She appears to be dressed in a skirt, blouse and (one hopes) sensible walking shoes; he, his hat at a jaunty angle, is clad in a coat, jodhpurs and riding boots, complete with a gentleman’s walking stick. They appear not just to be enjoying a day’s hike so much as contemplating the immense passage of time itself.

SEE AMERICA, the poster commands. The America in question is timeless, majestic and full of adventures. No

And that was the idea of the posters — to evoke a mood. One could feel the color and excitement of Times Square, the sea air in a lush garden in Puerto Rico, the spray from an eruption of Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park.

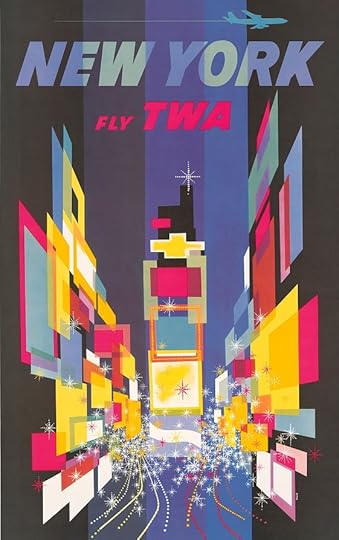

A Trans World Airlines poster for New York., with blocks of color showcasing the bright lights, big city idea of Times Square. Artist: David Klein. Prints and Photographs Division.

This golden era came to an end in the 1960s, when ad agencies began to go with flashy color photographs; the wide-angle view of the blue domes and white cliffside houses of Santorini, the caldera far below; the sunlight and golden beaches of Acapulco; snow-capped Mount Fuji, always from a distance, framed by blue sky above and green fields below. Lovely images, no doubt, but they put place over mood.

The Library holds thousands of travel posters from this era, designed to inspire viewers to get out on the road. Henry Ford’s Model T ignited a revolution in personal travel — you didn’t have to book passage on a train that was restricted to a certain track You could get in your car and go most anywhere, taking as much time and as many routes as you had the interest to explore. The family road trip was born.

Many of the Library’s collection of travel posters were created by the Work Projects Administration between 1936 and 1943. The WPA, a New Deal agency designed to help lift the nation out of the Great Depression, included Federal Project Number One, which hired writers, photographers, actors, artists and musicians to help keep the nation’s arts alive.

Other posters (like the blue cave) were created the United States Travel Bureau, designed to boost domestic tourism. They featured national parks and encouraged all to “See America” — the catchphrase on a number of them.

Blue skies and blue waters. Bermuda in the 1940s, as advertised by the nation’s Department of Tourism Artist: Adolph Treidler. Prints and Photographs Division.

But there was plenty of international travel, too, and the posters from the era reflect a similar approach of mood over place. The Bermuda Islands Department of Tourism and Trade Development was going all in on tropical romance and summer breezes in this lovely blue-water, blue-sky poster, pictured above. A horse-drawn carriage, wind coming in off the Atlantic and a secluded resort at water’s edge. That’s not a bad mood. Not at all.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

August 17, 2021

PBS Special: LeVar Burton and the National Book Festival

LeVar Burton. Photo: Robyn Von Swank.

LeVar Burton, fresh from a hosting “Jeopardy,” turns his attention to hosting a special edition of the Library’s 2021 National Book Festival, a one-hour special on PBS that is studded with some of the world’s brightest literary stars.

The show, “Open a Book, Open the World: The Library of Congress National Book Festival,” premieres Sunday, Sept. 12, at 6 p.m. ET (check local listings) on PBS, PBS.org and the PBS Video app. The show will feature 20 of the world’s most captivating authors and celebrities, ranging from actors Michael J. Fox and Lupita Nyong’o, to Nobel Prize-winning novelist Kazuo Ishiguro and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Annette Gordon Reed.

“Books open the world to us, fuel our imaginations and show us our common humanity, especially as we confront huge challenges in society,” said Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. “We’re proud to collaborate once again with PBS and public television stations nationwide to celebrate the power of reading from our national library.”

Burton, a longtime champion of reading, will host from the Los Angeles public library with Hayden appearing at the Library of Congress on Capitol Hill.

“I’m proud and honored to join Dr. Carla Hayden to explore the National Book Festival,” Burton said. “A good book can take you on a journey. After the last year, we’re all ready to plot a new course, and books can be an amazing compass. Join me for the National Book Festival as some of our nation’s leading literary voices bring us a sense of renewal, discuss their newest work and open up a whole new world of possibilities.”

The poster for 2021 National Book Festival. Artist:

Full interviews with each author will be featured in on-demand videos through the National Book Festival website and will be released Sept. 17. The 2021 virtual festival will invite audiences to create their own festival experiences from programs in a range of formats and an expanded schedule over 10 days, from Sept. 17 through Sept. 26.

The festival’s full lineup will be available online through videos on demand, author conversations in real time and live question-and-answer sessions, as well as a new podcast series with NPR. There will also be some in-person, ticketed events at the Library, should local COVID-19 restrictions allow gatherings.

To create the broadcast, the Library is collaborating with PBS Books, a national programming initiative produced by Detroit Public Television. PBS will distribute the one-hour National Book Festival broadcast to public television stations nationally.

“Books have been a lifeline for so many of us during this most difficult year. They have offered us an escape from the pandemic but also advice on how to cope with its challenges,” said Rich Homberg, president and CEO of Detroit Public TV. “We are delighted to be working once again with the Library of Congress, the National Book Festival and this incredible lineup of authors to celebrate our love of all things literary.”

The National Book Festival is made possible by the generous support of private- and public-sector sponsors who share the Library’s commitment to reading and literacy, led by National Book Festival Co-Chair David M. Rubenstein. Sponsors include: Festival Vice Chair the James Madison Council; Charter sponsors The Washington Post, Institute of Museum and Library Services, National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities; Additional generous support from the Library of Congress Federal Credit Union, Tim and Diane Naughton and Capital Group; Presenting Partner NPR; and Media Partner The New Republic.

You can llow the festival on Twitter @LibraryCongress with hashtag #NatBookFest, and subscribe to the National Book Festival Blog at loc.gov/bookfest.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

August 11, 2021

Researcher Stories: The Violins of George Yu

George Yu. Photo: Jon Cherry.

George Yu is an award-winning luthier based in Louisville, Kentucky, who models his handcrafted violins on rare Italian instruments, including a 1654 Amati violin at the Library .

You started your professional career as a software engineer. How did you end up making violins?

I was lucky to have parents who nurtured both my scientific and my artistic pursuits. I did some growing up in their chemistry labs while they were grad students, often asking, “Why?” — not from defiance, but from wanting to better understand. As a child, I started playing the violin.

Later, I graduated from the University of Waterloo [in Ontario, Canada] with a bachelor’s degree from the Systems Design Engineering program, which focuses on acquiring and integrating knowledge across multiple disciplines — an approach that would become very relevant to me as a violin maker. After working as a software engineer for nine years, I decided to combine two other disciplines with my scientific one — playing violin and creating with my hands — and become a violin maker.

I was accepted into the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City, graduating in 1999. Afterward, I apprenticed with Ken Meyer and Di Cao in suburban Boston, then established my own workshop in Toronto. In 2018, I moved to the U.S. to marry my husband, the Rev. Dwain Lee, pastor of Springdale Presbyterian Church in Louisville, Kentucky.

How does science inform your violin making?

For me, violin making is a confluence of music, art and science. Science involves constant learning about why violins sound good or bad. It’s an engineering problem that provides no ultimate, neat solution and raises questions. There’s no room for boredom.

Before I start working with a piece of wood, for example, I take measurements to get a good idea of its stiffness and density. While working only with wood that has both good stiffness and good density doesn’t guarantee that the finished violin will have great tone and responsiveness, it is a good starting point.

My choice of drying oils in varnish also draws on science. They vary in their number of double bonds and their sequencing along fatty-acid chains, affecting how the varnish chips, crackles and wears down. This is important to know in the process of antiquing, or making an instrument look like a replica from the 17th or 18th century.

Which instruments in the Library’s violin collection have inspired you?

I became aware of the Library’s collection of rare violins before heading off to violin making school in 1996. Bob Sheldon, who was then the curator of musical instruments at the Library, and Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford, his successor, kindly gave me access on multiple occasions to study, play and photograph them.

Every visit deepened and matured my acquaintance with the violins. The three that stood out for me, in chronological order, were the “Brookings” Amati (1654), the “Betts” Stradivarius (1704) and the “Kreisler” Guarneri del Gesù (circa 1730).

In playing them, I found that the Betts required a totally different approach from the others — faster and lighter bow strokes — and coaxing. I could not press or dig into it; otherwise, it would choke. There was no such issue with the Kreisler — I could press more, and it would respond by bringing forth even more of the beautiful, complex tone that was readily available in reserves; there was also an immediacy of sound. But the Brookings was my favorite. While it didn’t have quite the reserves of the Kreisler, it had more than the Betts; it also had a strikingly beautiful, rich, contralto voice.

The Brookings is named after Robert Somers Brookings, founder of what is now the Brookings Institution. He is said to have bought this violin on the advice of the virtuoso Joseph Joachim, a friend of Brahms. In 1938, Brookings’ widow presented the violin to the Library.

Describe one of your award-winning violins.

A violin of mine inspired by the Brookings Amati won double-distinction awards at the 2014 Violin Society of America Competition. Out of 246 violins entered that year, only three won awards in both categories of tone and workmanship. In creating the instrument, I made use of CT scans of the Brookings that were made through a project with the Smithsonian Institution.

Where are your instruments being played?

My instruments are being played by professionals in the New York Philharmonic, Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Lyra Baroque Orchestra and other ensembles. They are also being played by students at top music conservatories.

How has it been to do research at the Library?

Bob and Carol Lynn have been a great pleasure to work with! I hope to arrange more visits in the future to further study the Library’s violins — there is always more to learn.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

August 9, 2021

Marie Tharp: Mapping the Ocean Floor

Heinrich Berann’s 1977 painting of the Heezen-Tharp “World Ocean Floor” map, a landmark in cartography. Geography and Map Division.

Mike Klein wrote a short piece for the Library of Congress Magazine’s July/August issue on the Heezen-Tharp map, pictured above. That article has been expanded here.

Marie Tharp was well-suited to the task of interpreting the texture and rhythm of the Earth’s surface, including the ocean floor — a space almost entirely unknown to humans, even after they began sailing the seas. A scientist, she had a background in mathematics, music, petroleum geology and cartography.

But she was a professional woman in the American mid-century in a field overwhelmingly dominated by men. She played a major role in one of cartography’s greatest achievements, mapping the sea floor for the first time in history, documenting a vast mountain range in the Atlantic Ocean. The maps she and her longtime collaborator, Bruce Heezen created then verified the theory of continental drift — the idea that the Earth’s continents shifted across the ocean bed due to the movement of tectonic plates. Continental drift is now fundamental to understanding how our planet came to be.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime—a once-in-the-history-of-the-world—opportunity for anyone, but especially for a woman in the 1940s,” she wrote in a 1999 essay.

Tharp donated the papers of their research to the Library in 1995, then helped Library staff arrange the tens of thousands of items for future researchers. It is by far the largest manuscript/research collection in the Geography and Map Division, comprising maps, journals, research papers, letters, correspondence and geologic and cartographic data. It culminates in the depiction of the map in the painting above, the Heezen-Tharp “World Ocean Floor” map. It is still in use today and documents the 40,000-mile undersea mountain ranges that are critical to understanding how and why the Earth’s continents came to be where they are.

This collection is part of a larger archival project that documents some of the pioneering geographers of the 20th century, include Roger Tomlinson, one of the primary developers of the Geographical Information System (GIS), and John P. Snyder, who worked on the mathematics that enables mapping from space.

“Tharp’s work certainly provided evidence and weight to the theory of plate tectonics, but her work is really about seafloor spreading, which occurs at the mid-ocean ridges that she was the first to map,” says Paulette Hasier, chief of the division.

Marie Tharp with James Billington, former Librarian of Congress. Photo: Rachel Evans.

Tharp’s role as a top-tier female scientist who largely worked behind the scenes might prompt comparisons to the women at NASA’s space program in the 1960s, as featured in the book and film, “Hidden Figures.” But Hasier says the better comparison would be to the “Harvard Computers,” female scientists who worked at the Harvard Observatory in the early 20th century. Astronomers such as Annie Jump Cannon, Williamina Fleming and Florence Cushman helped develop and codify a classification system for some 300,000 stars, thus rendering the universe more of a known entity.

“Tharp, like these women, had a talent for visualizing data, something we take for granted today but required real geometric intuition before the widespread use of computers,” Hasier said.

Before Heezen and Tharp’s work, maps of the world showed three-fourths of it — the oceans — to be a flat blue surface. Sailors knew of reefs, channels and sand bars, of course, but not much else of what lay further below. Geologists had only a vague idea of the depths, but it was largely presumed to be flat and featureless.“I think our maps contributed to a revolution in geological thinking, which in some ways compares to the Copernican revolution,” she wrote in an essay included in “Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University: Twelve Perspectives on the First Fifty Years 1949 – 1999.” “Scientists and the general public got their first relatively realistic image of a vast part of the planet that they could never see.”

In many ways, she had been working her entire life to make such discoveries.

Born in Ypsilanti, Michigan, in 1920, Tharp grew up moving to place to place, as her father was a soil surveyor for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The family moved seasonally to follow his work, a peripatetic life in which she attended more than two dozen schools by the time she graduated high school. It left her, she later said, with a residual awareness of land, soil and the way the Earth is shaped.

Her father’s mantra: “When you find your life’s work, make sure it is something you can do, and most important, something you like to do.” At Ohio University, she didn’t find much she liked that women were allowed to do. The outbreak of World War II provided a break in the patriarchal system, as men were called away to war. In their absence, women took on many roles in the workplace they had not before. At the University of Michigan’s geology department, the staff began to allow female students. In 1943, Tharp was one of 10 young women who enrolled.

This led to unfulfilling work in the petroleum industry, which led to an unfulfilling math degree from the University of Tulsa, which led to an unfulfilling proposed job the American Museum of Natural History in New York, which, finally, led to a job at Columbia University’s Lamont Geological Observatory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory). There, she soon met Bruce Heezen, another bright young star, with whom she would work for the next quarter century. The partnership was necessary, as women were not allowed on sea-faring research ships at the time. For years, while he gathered data at sea, she developed the data on maps back at the lab.

They began compiling thousands of files of data about the ocean floor (mostly sonar readings from U.S. Navy ships). The sonar soundings were rough, incomplete, and taken at different international measuring standards. Still, she began to map out data that showed a huge north-to-south mountain range underneath the Atlantic Ocean, bordered by a rift valley.

When she showed it to Heezen, he dismissed it as “girl talk” and scoffed that it looked “too much like continental drift,” then considered an outlandish theory.

“But I thought the rift valley was real and kept looking for it in all the data I could get,” she wrote. “If there were such a thing as continental drift, it seemed logical that something like a mid-ocean rift valley might be involved. The valley would form where new material came up from deep inside the Earth, splitting the mid-ocean ridge in two and pushing the sides apart.”

By the 1970s, as their work progressed, after they had charted the locations of tens of thousands of undersea earthquakes, and as their findings were collaborated by other scientists from around the world, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge became an obvious part of an undersea mountain range that stretched around the world.

The pair produced maps of individual oceans in partnership with National Geographic that culminated in the iconic worldwide panorama above in 1977, painted by Austrian artist Heinrich Berann. Ironically, Heezen died of a heart attack on a research cruise just a few months before the map’s publication.

She summed it all up this way:

“I worked in the background for most of my career as a scientist, but I have absolutely no resentments. I thought I was lucky to have a job that was so interesting. Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge that went all the way around the world for 40,000 miles—that was something important. You could only do that once. You can’t find anything bigger than that, at least on this planet.”

Subscribe to the blog — it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

August 5, 2021

Maya Blue and the Vessels of the Diving Gods

This guest post is by John Hessler, curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Archaeology & History of the Early Americas. It is part of a series, Excavating Archaeology.

The ceramics created by ancient Maya potters make for some of the most vibrantly colored objects that survive in the archaeological record of the Americas. Through the centuries, a great deal of the coloration on many of the surviving examples has eroded, its brilliance lost to the ravages of time. Occasionally however, there are rare survivals that give us an indication of just how colorful was the Pre-Columbian Maya world.

In the Kislak Collection, there are two extraordinary vessels from Quintana Roo, Mexico, which date from the 13th to 15th centuries. These two small ceramic pots, each measuring only a little over four inches tall, are made from red ceramic and display a vivid spectrum of colors.

Diving god vessel from Quintana Roo. Jay I. Kislak Collection. Author photo.

Both of these pots are painted in the style of Mixteca-Puebla forms found in central Mexico and around the area of Oaxaca. The subjects of the vessels are diving figures, so called because they are pictured as plummeting headfirst from the sky. Each vase is painted with angular lines running across their faces, a mark usually associated with a postclassic version of the Maya maize god. Both vessels show the figures holding offerings.

Three-dimensional model of one of the diving god vessels from Quintana Roo. Jay I. Kislak Collection. GIF by author.

The angled lines on the face, along with other symbolic colorations, reveal that these pieces are cultural hybrids, with the late variant of the Maya maize god, known as “Bolon Mayel,” merging with features of the Central Mexican version “Centeotl,” and the god of flowers and plants, “Xochipilli.”

Madrid Codex, showing a diving god. Jay I. Kislak Collection.

The diving god appears in many forms and in many places in Maya art — stone carvings, wall paintings and in one of the four surviving Maya books, the Madrid Codex. It’s pictured above. The diving god is upside down at the top of the blue section.

The painting on the two vases is also special.

The Maya made their pottery by hand, without a potter’s wheel, a process that involved many steps. The first, of course, was selecting and preparing the clay. Then the potter might fold into the mix different additives, known as tempers, such as ground limestone or volcanic ash.

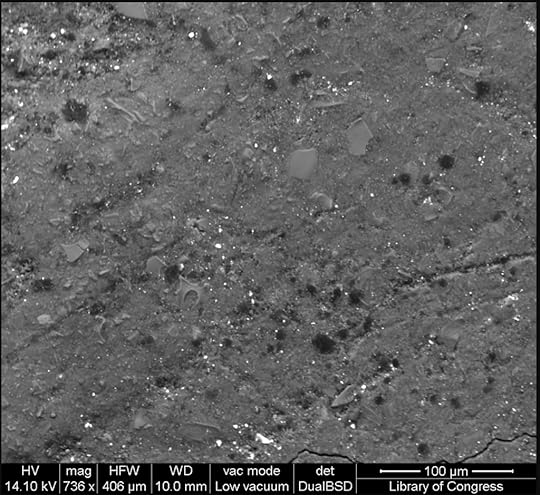

Scanning electron microscope image of the Maya ceramic matrix showing the additives and temper in the clay. Preservation Testing and Research Division.

Before firing in a kiln, the surface would typically be covered in slips, which are mixtures of minerals and pigments. They are applied to give the vessels their color, shine and brilliance. In the the diving god pieces above, there was no slip applied. They were painted after they came out of the firing kiln.

Magnified section of the painted surface. LED microscope photo by author.

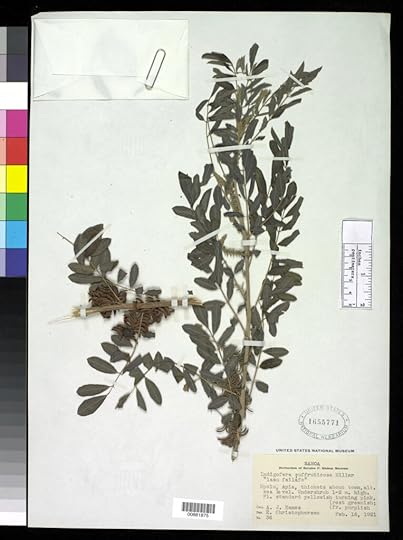

One of the colors is an important innovation. The bold and distinct blue paint, which we see on the ear-spools, is called Maya blue. The pigment is a composite of ingredients, primarily a mix of blue indigo dyes derived from the leaves of Indigofera suffruticosa plants (the same dye in your blue jeans). It is combined with palygorskite, a natural clay that is important to the longevity of the color.

Indigofera suffruticosa leaves from Mexico. Smithsonian Institution, Museum of Natural History, Botanical Collections.

The stability of Maya blue, and the reason it does not fade on ancient ceramics (like it does in your jeans) is because the palygorskite particles in the paint form a kind of lattice, mixing with and trapping the indigo molecules. This structure makes the paint amazingly resistant to natural bio-corrosion, resulting in the survival of the beautiful blue color we still see on the vessels today.

A diving god vessel with Maya blue paint on the ear-spool. Jay I. Kislak Collection. Author photo.

Maya blue, and many of the other colors found painted across ancient Mesoamerica, are striking in their brilliance and composition, and are a testimony to the artists who experimented with the wide variety of plants, minerals, and binders needed to create these colors. Nearly indescribable to us today, and whose original names have, in many cases, been lost to history, these paints are clearly examples of what the 19th century art critic John Ruskin meant when he said, “It is the best possible sign of a color when nobody who sees it knows what to call it.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

August 2, 2021

Glen Campbell, Jimmy Webb and “Wichita Lineman”

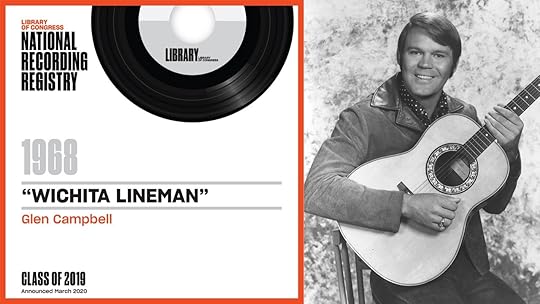

Glen Campbell’s 1968 recording of “Wichita Lineman by Jimmy Webb, was inducted into the National Recording Registry.

The Library’s National Recording Registry includes 1968’s “Wichita Lineman,” written by Jimmy Webb and first recorded by Glen Campbell. Kent Hartman, whose 2013 book “The Wrecking Crew” detailed the L.A. music scene that produced Campbell, wrote this essay for the Now See Hear! blog, drawing on his research. This version has been slightly adapted.

Glen Campbell had bigger hits during his illustrious career, but no song of his has stood the test of time or packed more of an emotional wallop than “Wichita Lineman.” It became Campbell’s oft-cited favorite out of the hundreds of songs he released during his Country Music Hall of Fame career. Yet only a serendipitous series of events allowed this platinum record to become what is now considered an American classic.

In the early spring of 1968, while sitting behind a funky green piano, high in the Hollywood Hills inside an old mansion that used to be the Philippine Embassy, the songwriter Jimmy Webb heard his telephone ring. As the author of the recent Grammy-winning single “Up, Up and Away” by the 5th Dimension, the red-hot Webb had been sequestering himself in an effort to write some new material.

The progress was slow — Webb was a perfectionist —and Campbell’s call came as a welcome distraction. Recent friends, the two had shared an almost immediate connection upon meeting. As both men later recalled in separate interviews with me, the call went something like this:

“Jimmy — hey, it’s Glen Campbell.”

“Glen, good to hear from you, man! What’s goin’ on?”

“Well, my producer, Al DeLory, and I are over here at Capitol cutting a new album and we’re short on material. We need something really strong. Do you think you could write us another ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’?”

Both an unexpected and heavy request, it gave Webb pause.

Campbell was referring to the crossover country smash that Webb had penned and given to him the prior year. It had provided Campbell with the first meaningful chart success of his career. Yet he wanted more; needed more. He was in his mid-thirties, and pop stars don’t have forever. Campbell knew that it took a Top 10 single to become headlining act, something he had dreamed of since his days playing the clubs in Albuquerque a decade before. And he was determined to make that leap.

Writing a hit song is hard enough, let alone one made-to-order. But Webb liked a challenge. And he knew that with Campbell’s career on the rise, there might be some good publishing money in the deal.

“Okay,” Webb said after some thought. “Let me see what I can do.”

He had a policy against copying a previous hit — even if it was his own — but he nonetheless thought that once again employing a geographical reference in the title might be a good start.

Sometime earlier, Webb had been driving through a flat and remote area of Oklahoma, his native state, absorbing the almost surreal nature of its isolation and seemingly endless horizons. He passed by a utility worker perched high on a telephone pole. The curious image of the anonymous, lone figure toiling in the heat in the middle of nowhere stuck in Webb’s mind. What might be the circumstances of this solitary man’s life? What were his thoughts?

Turning back to his piano after the phone call with Campbell, Webb spent the next couple of hours sketching out a song about the mysterious individual he had encountered on that lonely stretch of highway, then asked Campbell and DeLory to swing by the house that evening to take a listen.

“It’s not finished yet,” Webb warned as they sat down. “There’s no third verse.”

As Webb began playing and singing the basics of his new tune, Campbell flipped. He knew it was a hit. A story of desolation and longing, it spoke to the human condition, the universal need for love. The imagery about the singing in the wires and searching in the sun for overloads was out of this world.

“What’s it called?” Campbell asked.

“ ‘Wichita Lineman,’ ” Webb said.

***

Wondrous things can happen in a recording studio when inspiration becomes contagious.

Inside the subterranean confines of Capitol A, Campbell and DeLory walked musicians through the charts for the song. Something kept bothering the bassist, Carol Kaye. She and Campbell had played together as part of the Wrecking Crew, a group of secretly-used, top-notch Hollywood-based session musicians who played on dozens of Top 40 hits. They were good friends.

Looking over the chord sheets, Kaye saw that the tune lacked an identifiable opening lick. She had noticed the same deficit about the original version of Sonny and Cher’s “The Beat Goes On.” She had added a nine-note opening bass riff, then repeated it over and over, turning what at first had been a rather mundane rhythm track into a certifiable earworm.

Here, drawing on her jazz background, where less almost always meant more, Kaye quickly worked out a descending six-note intro for Campbell that she thought might do the trick.

Campbell thought it was perfect. But he also loved the tone of her bass. It was a Danelectro, a six-string, solid-body electric bass guitar made out of Masonite. It was often used in studios on pop recordings to add a higher sound than that of a standard Fender electric bass or an acoustic stand-up bass.

Campbell asked Kaye if he could borrow the guitar to play a solo to fill the space for the third verse that Webb had never finished. An unconventional but brilliant choice, the deep, resonant passage scored a direct hit, giving the song just the right quavering, tremolo-fueled melancholic interlude.

Webb chipped in with some inspiration of his own. Showing off his vintage Gulbransen church organ to Campbell one afternoon at his house, Webb mentioned that the keyboard’s unique bubbling sound evoked what he imagined to be the noise of signals passing through the telephone wires. As his lyrics said, “I hear you singing in the wire/I can hear you through the whine.”

Campbell was so taken with the idea that he had a company immediately come over and dismantle the monstrous organ and then reassemble it in the studio. Webb himself played just three notes on it, over and over, during the song’s fade. It proved to be the final piece to a masterfully executed production puzzle.

With Campbell’s plaintive vocals adding just the right touch of wistfulness and heartache, “Wichita Lineman” did indeed become the Top 10 hit he had so desperately sought. There would be no more anonymous guitar playing on everybody else’s records for this country boy. No more wondering whether he really had what it took to break out, to headline his own shows.

While “Wichita Lineman” rocketed to No. 3 on the national pop charts (and No. 1 on country charts), it became Campbell’s springboard to more success, including his own television show that ran for four seasons. As Campbell remarked to the British Broadcasting Corporation many years later, mentioning one of the song’s lines: “‘I want you for all time,’ I always say that to my wife, because it cheers her up.” There can be no greater poetic coda than that.

Kent Hartman is the bestselling author of “The Wrecking Crew,” along with “Goodnight, L.A.” and the forthcoming “A Cool Dark Place.” [Essay copyright: Kent Hartman]

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers