Library of Congress's Blog, page 42

July 28, 2021

Jade Snow Wong: The Legacy of “Fifth Chinese Daughter”

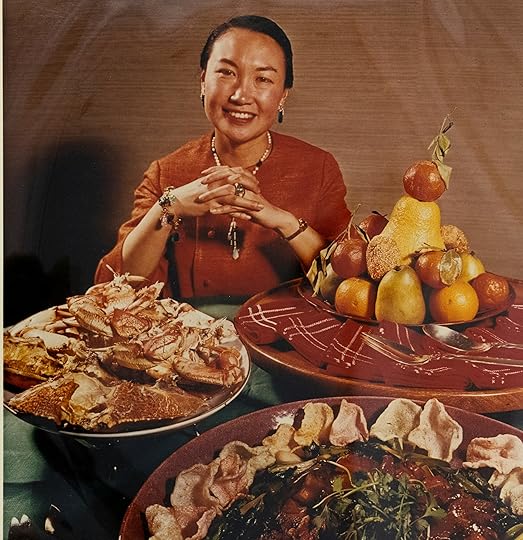

Jade Snow Wong, in a 1965 San Francisco Examiner article. Asian Division. Photo of original: Shawn Miller.

Jade Snow Wong published “Fifth Chinese Daughter” in 1950, and it has been part of American literature ever since. The memoir of a young Chinese American woman coming of age in San Francisco’s Chinatown, torn between her family traditions and her American ambitions, it has lived several lives in the intervening three-quarters of a century.

“I wrote with the purpose of creating better understanding of the Chinese culture on the part of Americans,” she wrote later, a sentiment she would use throughout her life.

Lauded by critics, it became a bestseller in an era when the Chinese Exclusion Act had only recently been lifted. It was a feel-good story about a determined young Chinese woman (Wong was 28 when the book was published) who said that America was a land of opportunity, if only you worked hard for your dreams. Racial slights and discrimination scarcely exist in the book and are quickly and cheerfully overcome. The Chinese Exclusion Act is not mentioned at all.

It presented such a positive view of Chinese immigrant life, in fact, that in 1953, the State Department sent Wong and her book on a four-month tour across Asia, touting American ideals against the growing spread of communism in the region.

By the late 1960s and 1970s, times had changed. A new generation of young Asian Americans dismissed the book as naïve, too accommodating of white readers’ stereotypes, too willing to spout the U.S. government’s narrative at the expense of their lived reality. She was using her individual success story in disregard of prevailing anti-Asian discrimination, they said.

U.S. and international editions of “Fifth Chinese Daughter.” Asian Division. Photo: Shawn Miller.

As it has fallen further into the past, the book has settled into the national narrative as a lasting portrait of Chinese American life at the midcentury – stilted, sometimes perceptive, sometimes shading the truth in favor of an up-by-the-bootstraps narrative.

“It has a very high place as part of the historical record,” says Leslie Bow, a professor of English and Asian American Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who wrote the introduction to the book’s 2019 Classics of Asian American Literature Edition. “Part of that history is having these documents (in the Library’s collection) that tell a bit more of an ambiguous story; the history that was, as opposed to the history that you want it to be.”

Wong was, by any account, ambitious and multitalented. In her adult life, she and her husband, Woodrow, ran a successful travel agency and import-export business, and yet she is perhaps best known today as a ceramic artist whose works have been shown by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

Her family donated her papers and dozens of her ceramic pieces to the Library in 2009, three years after her death. The collection is now part of the Asian American Pacific Islander Collection in the Asian Division. (It has not been digitized and is available only at the Library.)

Her son, Mark Ong, talked about her dual nature in a 2020 interview with the Asian Art Museum. He said it was a “living process, how she could be a Chinese woman, how she could be a successful artist, how she could be a businesswoman, a wife, a mother, a civic leader as well.”

“Daughter” was one of the first portrayals of Chinese life in the United States, following the works of the Eaton sisters a couple of generations earlier. (Winnifred and Edith Eaton, children of a British father and Chinese mother, wrote novels and non-fiction in the U.S. and Canada in the first two decades of the 20th century, each gaining acclaim.) Wong painted a clear, concise picture of growing up in San Francisco in the 1920s and 1930s. She wrote about herself in the third person, as if she was describing someone else:

“Until she was five years old, Jade Snow’s world was almost wholly Chinese, for her world was her family, the Wongs. Life was secure but formal, sober but quietly happy and the few problems she had were entirely concerned with what was proper or improper in the behavior of a little Chinese girl.”

Jade Snow Wong in her pottery workshop. Asian Division. Photo of original: Shawn Miller.

This balancing act of Chinese home and American life still resonates with young Asian readers, says Bow, herself the child of Chinese American parents.

But over time, cracks in the narrative and its underlying philosophy appeared. It became regarded as a tourist-level snapshot of Chinese American life for white readers who wanted to dip a toe into the cultural pond, but not deal with the harsher realities of poverty, racism and discrimination.

For example, her father, who ran a small sewing company that turned out overalls (the family lived on a floor of the factory) had been in the country for decades, but was only able to become a naturalized American citizen after she had graduated from college due to blatantly racist immigration laws.

Further, Jade Snow was indeed her father’s fifth daughter, but her mother’s first. Her father’s first wife had died, and the second had assumed her identity, a fact omitted in the book. This impersonation was a common way for Chinese immigrants to evade the severe restrictions placed on them by the U.S. – a country she was nonetheless touting as a land of freedom.

And lastly, as her yearbook, passport and other documents show, she went by her American name of Constance, or Connie, throughout her life, even at home. But, in the book, she writes as if people instead called she and her siblings by their Chinese names. Critics came to scoff that this was blatant pandering to white readers’ taste for the exotic.

Still, the book has endured for its clearly written prose, for its evocation of a time and place, and for its appealing story of a determined young Chinese woman who found her way to success in American life.

“Chinatown in San Francisco teems with haunting memories, for it is wrapped in the atmosphere, customs and manners of a land across the sea,” she wrote at the beginning of the book. “The same Pacific Ocean laves the shores of both worlds, a tangible link between old and new, past and present, Orient and Occident.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 26, 2021

America on the Road: The Family Vacation by Car

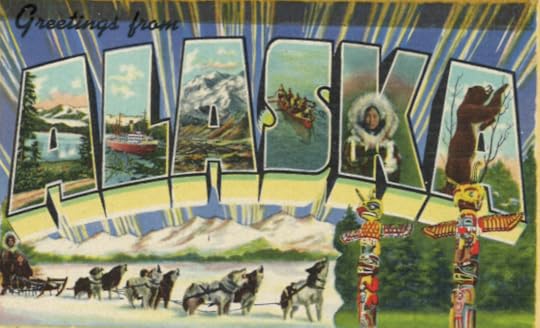

Alaska postcard in the 1950 travel journal of sociologist Rilma Oxley Buckman. Manuscript Division.

This is a guest post by Joshua Levy, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

In 1960, John Steinbeck set out on a months-long road trip to reacquaint himself with his country. He returned not with clear answers but with his head a “barrel of worms.” The America he saw was too intertwined with how he felt in the moment, and with his own Americanness, to permit an objective account of the journey. “External reality,” he wrote, “has a way of being not so external after all.”

Pandemics aren’t the only reason Americans have found sanctuary in our homes, or the only anxious times we’ve itched to escape them. The American road trip was first popularized during the auto camping craze of the 1920s, with its devotion to freedom and communing with nature, but it was democratized after World War II. The golden age of the American family vacation came during the very height of the Cold War. It was a time when, according to historian Susan Rugh, the family car became a “home on the road… a cocoon of domestic space” in which families could feel safe to explore their country.

The trips 2oth-century Americans took, to national parks and resorts and historic sites, generated a wealth of travelogues and other sources that often communicate far more about the traveler than the road taken. They can help us understand our own moment as well. Earlier this year, just 29 percent of Americans felt comfortable taking a commercial flight, but 84 percent were comfortable using their own vehicles for a road trip. During the pandemic, tourism suffered but road trips surged. Driving into the great outdoors again felt like a safe escape.

The Manuscript Division is full of road trip stories, not because it maintains specific road trip collections but because automobile travel has been so central to modern American life. Items in the division range from administrative records mapping out early guidebooks, to breathless journals recounting shared adventures, to testimonials of discrimination faced at roadside gas stations, restaurants and hotels. Together, they tell the story not of one America, but of many.

Researchers can find in the papers of the Works Progress Administration the records of the American Guide Series, a Depression-era project to create richly textured guidebooks of all of America’s states and major cities and some of its highways and waterways. The series generated 378 books and pamphlets altogether, and employed subsequently celebrated authors like Richard Wright, Eudora Welty and Zora Neale Hurston.

Poster for “A Guide to the Golden State,” WPA American Guide series for California. Prints and Photographs Division.

The books were needed. Railroads, one of the 19th century’s great symbols of modernity, had run along immovable tracks following set timetables. Rich and poor travelers alike were essentially reduced to pieces of baggage. Early automobiles promised a pathfinding freedom, but motorists found America’s intercity roadways disjointed and virtually unmarked. Colossal early touring guides like the Automobile Blue Book prescribed tedious turn-by-turn directions through the maze, but offered little insight into local communities.

The WPA guides blended an attention to local history, culture and commerce with a literary sensibility. The project’s ambition still startles. An early prospectus promised to advance efforts to “preserve national literacy and historic shrines, to exploit scenic wonders and to develop natural advantages such as mines and quarries.” Steinbeck later called the guides “the most comprehensive account of the United States ever got together.” Staffers, sometimes road-tripping to fact check their work, labored to create a nuanced, encyclopedic account of what mattered about America — one mapped out in routes Americans could drive for themselves.

Yet not all Americans traveled those routes with the same ease. The records of the NAACP, held by the Manuscript Division, contain hundreds of testimonials speaking to the uncertainties and humiliations Jim Crow-era African Americans faced when they ventured from home. For these motorists, the automobile’s promise of freedom coexisted with segregated buses and trains and a range of limitations on their mobility. Black drivers experienced the open road, according to historian Cotten Seiler, as “both democratic social space and racial minefield.” Automobiles seemed to offer a real escape from Jim Crow, but one that always lay just beyond the horizon.

As a result, excursions often turned sour. One letter, submitted in 1947 by a high school science teacher, details an afternoon road trip to a state park near Albany, “for the purpose of sightseeing and enjoying the natural beauty of the State of New York.” When a hotel bartender within the park twice refused service to the teacher and a Jewish colleague, he insisted the hotel be “made to pay” for his “humiliation and damage to my pride.” Similar testimonials, of injustices on buses and trains and at roadside stops, illustrate the road trip’s unfulfilled promise for African American travelers. But they also suggest the allure of commanding one’s own vehicle and of sidestepping more communal forms of transit.

Travelogues in collections of personal papers offer another dimension still, documenting both cosmopolitan tourism and nostalgic returns home. A travel journal in the papers of sociologist Rilma Oxley Buckman describes a footloose road trip from Indiana to Alaska, taken in 1950 with a Purdue colleague in a late model Nash. The “lady campers” had met in Yokohama just after the war, both working with the U.S. military. Adventuring their way north, they socialized and took snapshots. They noted the “Huckleberry Finn riverscapes” of Illinois and Alaskan roads “wobbly as a wagon trail.” But their lives in Asia repeatedly intervene, from birds that resembled Korean magpies to the Japan-like hot springs of the Canadian Rockies and then to worrying radio reports about the start of the Korean War.

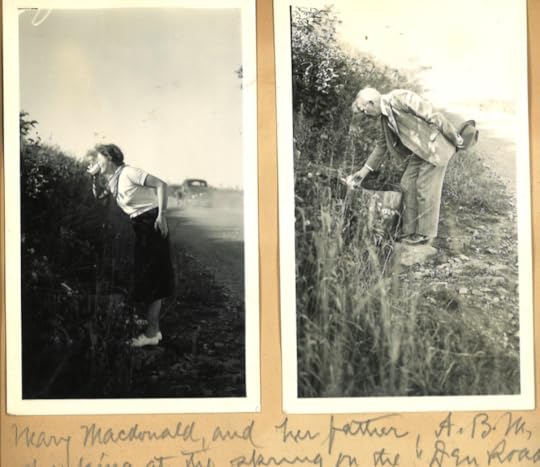

Page from A.B. McDonald scrapbook, with father and daughter drinking from a roadside spring. Manuscript Division.

A scrapbook made by journalist A.B. MacDonald recounts a road trip with his daughter Mary in 1938, just four years before he died. From Kansas City to his boyhood home in New Brunswick, father and daughter visit the old “homestead,” drink at a roadside spring where the family once watered their horses and catch up with boyhood friends. Captions are written two years later in a shaky hand, from MacDonald’s sickbed. By that time, Mary had tragically passed away. Above his recollections of an old schoolmate’s home, whose bed of nasturtiums both had admired as a “perfect blanket of gold and crimson,” two flowers just received by mail are pressed into the paper. There, MacDonald writes, “Later — I did put two of the flowers on Mary’s grave, and there they remained for several weeks. She knew, of course she did.”

And there are more. The Library’s manuscript collections show suffragists embracing the automobile as a vehicle for women’s liberation and activists like Sara Bard Field staging cross-country journeys to gain publicity for the cause. They show Carlos Montezuma, cofounder of the Society of American Indians, defending the rights of indigenous Americans to purchase automobiles without government permission and to travel as they please. We even find political satirist Art Buchwald in a comically overloaded Chrysler Imperial, on a 1958 road trip from Paris to Moscow in order to test whether such a drive can be made “without being arrested.”

Road trips appear in unexpected places, and they can be revealing in unexpected ways. And in a nation knitted together with highways, cars long ago became Americans’ liberating, frustrating, memory-making homes on the road.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 22, 2021

Library’s Junior Fellows: Online Interns Get the Job Done

Tania María Ríos Marrero, one of the 2021 Library Junior Fellows, with her digital research project.

This is a guest post by Leah Knobel, a public affairs specialist in the Office of Communications.

For 30 years now, the Library’s Junior Fellows program has provided undergraduate and graduate students with experiences in everything the world’s largest library has to offer. This year’s 10-week program was held virtually for the second year in a row, due to COVID-19 precautions. The junior fellows logged on daily, launched their individual research projects, participated in weekly professional development sessions and worked with Library staff.

In an online presentation, this year’s class of 42 fellows shares glimpses of their work. Their projects include a data-driven approach to communication and outreach for the Copyright Office; a digitization effort to improve access to a collection of posters amassed from across sub-Saharan Africa; an exploration into the history of arithmetic; a digital Story Map of Caribbean women poets from the PALABRA archive; and contributions to the Congressional Research Service’s ongoing Supreme Court Justice Project.

“The Junior Fellows program, like most everything in our world, faced unprecedented challenges with the onset of the pandemic,” said Kimberly Powell, chief of talent recruitment and outreach in the Library’s Human Capital Directorate. “During this second virtual year, we expanded on lessons learned and stakeholder feedback to prioritize changes and processes to prepare for and expand display day.”

Interns were equipped with a virtual Library workstation, with access to Skype for Business and Zoom accounts when they started in May. Then they set to work.

Shlomit Menashe, a rising senior studying information science at the University of Maryland, College Park, spent her summer working to increase the discoverability of 1,200 uncatalogued Hebrew prayer books. During her work, she came across a Hebrew prayer book printed in Constantinople, or present-day Istanbul, in 1823. As Menashe’s own family emigrated from Turkey, her interest was piqued.

For her project, she decided to learn more about events at the end of the 15th century that brought Jews to the Ottoman Empire, which in turn became a center of Hebrew printing.

“Working on my project for display day was especially meaningful in that it provided me an opportunity to connect with and learn more about my family’s Sephardic heritage,” Menashe said. “My grandfather even has a haggadah, a prayer book traditionally read on the first two nights of the Jewish holiday of Passover, which was passed down from his grandfather who used it while living in Izmir, Turkey.”

Joe Kolodrubetz will begin the final year of his J.D. at the George Washington Law School this fall. During his summer fellowship in the Law Library, Kolodrubetz created metadata for the library’s foreign legal gazettes collections. A legal gazette is an official source of law published by a foreign government to announce the decisions of courts, legislatures and executives in that country.

Kolodrubetz cites the few days he spent working with Cypriot gazettes as the highlight of his summer. His knowledge of ancient Greek was directly transferable to the Greek of the Mediterranean island.

“It was still a bureaucratic text,” Kolodrubetz joked, “but I enjoyed utilizing my Hellenic knowledge!”

Tania María Ríos Marrero is set to complete a master’s degree in library and information science at the University of Washington’s iSchool in spring 2022. While interning in the Science, Technology and Business Division, Ríos Marrero built a Story Map contextualizing a selection of Farm Security Administration photographs taken in Puerto Rico in the mid-20th century. The project draws connections between aspects of land use, food production and social movement in Puerto Rico at the edges of the industrial and modern era.

“I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to interact with the photographs in a … tangible way,” said Ríos Marrero. “I hope that this Story Map is just the beginning of my personal research and engagement with this collection.”

The Junior Fellows program is made possible by a gift from Nancy Glanville Jewell, the late James Madison Council member, through the Glanville Family Foundation; the Knowledge Navigators Trust Fund; and by an investment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

July 20, 2021

Olympic Gold: Harrison Dillard and Military Athletes

Harrison Dillard, bottom, wins the Olympic gold medal in a photo finish. Photo: Alamy Stock photo. Also in Prints and Photographs Division.

This post draws from an article by Megan Harris, a reference specialist in the Veterans History Project, in the Library of Congress Magazine. It’s been expanded here.

London, summer 1948. All eyes are on the first Olympic Games held since 1936. After years of war, countries from around the world meet not on the battlefield, but on the track, in the swimming pool, inside the boxing ring.

At Wembley Stadium, six sprinters crouch on the track for the finals of the 100-meter dash. The gun sounds and in 10.3 seconds it’s over. The race is so close that a photograph is used to declare the winner.

The image is striking. Six of the world’s fastest men, caught seemingly in mid-flight — none of their feet are touching the ground — are frozen in a furious burst of speed. They seem to be out-running their own shadows. It’s appears to be as much a ballet as it is a sprint.

But the photo makes it clear: William Harrison Dillard, at the bottom of the image, won the gold and takes the honorary title of the “fastest man alive.” His arms and hands are flung out and up, palms open, his right leg bent backwards at the knee, the toes of that foot pointing straight toward the heavens.

Fellow American Barney Ewell — who initially celebrated with arms raised, thinking he had won — took the silver. Panama’s Lloyd LaBeach edged the U.K.’s Alastair McCorquodale for the bronze.

Dillard’s feat was all the more stirring because, three years earlier, he had not been sprinting at a university or track club, but dodging mortar fire in Italy as part of the U.S. Army’s 92nd Infantry Division, a segregated unit known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

“I was extremely proud” of being a Buffalo Soldier, he said in a 2008 interview with the Library’s Veterans History Project.

As the 2021 Olympics get set to begin, it’s worth remembering that Dillard — along with Charley Paddock and Mal Whitfield — were among the armed services’ greatest Olympic champions in a long list of military and athletic greatness. The Department of Defense lists 19 members of the armed services participating in this Olympics.

Paddock, who served in the U.S. Army Field Artillery in World War I, won two golds and two silvers in the 1920 and 1924 Olympics. (You might remember him as the cocky American in “Chariots of Fire.”) He returned to the service during World War II and was killed in a 1943 military plane crash in Alaska. Whitfield, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen, and Dillard won a combined nine medals at the 1948 and 1952 Olympics, seven of them gold. Four of the golds belonged to Dillard; five of the total belonged to Whitfield. All three are in the U.S. Olympics & Paralympics Hall of Fame.

Dillard’s Olympics got off to a disastrous start. He failed to quality for the finals in his signature event, the hurdles, even though he was the world record-holder at the time (he hit several hurdles). He barely qualified for the 100 meters final and thus had to run in the far outside lane.

But perhaps most striking was that he had attended the same high school in Cleveland, Ohio, as Jesse Owens. Owens won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, humiliating German leader Adolph Hitler and his ideal of Aryan supremacy. Dillard, about a decade younger than Owens, had been 9 when he had watched Owens, then a high school senior, run at East Technical High back home. He idolized Owens, vowing to grow up to be just like him.

Since the Olympics were cancelled due to World War II in 1940 and 1944, the 1948 Olympics were the first held since Owens had accomplished his feat. And so it was that the East Tech guys were, in consecutive Olympics, both dubbed the fastest men on the planet.

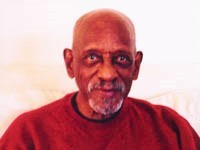

Harrison Dillard, at his home in Shaker Heights, Ohio, 2008. Photo: Veterans History Project.

Born in Cleveland, Dillard graduated from East Technical, then went to Baldwin-Wallace College (now Baldwin Wallace University) on a track scholarship. During his sophomore year, he was drafted and later assigned to the 92nd.

By 1944, he was in combat in Italy. For six months, the 92nd slowly advanced, liberating towns as they went. In his VHP interview, Dillard recalled mortar fire, minefields, the bravery of his comrades. He also remembered Italian civilians, their villages destroyed, begging U.S. servicemen for food.

With the end of the war, Dillard’s focus turned from survival to running. He would go on to being one of the greatest sprinters and hurdlers of his generation.

“I grew up physically in the service…but more than that it teaches you self-reliance and discipline,” he said in his VHP interview. “Military discipline is second to none.”

While stationed in Europe during the occupation, he won four gold medals at the G.I. Olympics. Gen. George Patton, whose papers are at the Library, had placed fifth in the pentathlon in the 1912 Olympics, was there. A reporter about the fiery general about Dillard’s performance. “He’s the best (expletive) athlete I’ve ever seen,” Patton responded.

He was the best athlete a lot of people ever saw. At the London Games, he won gold medals in 100-meter dash and the 4×100 relay. Four years later, at the Helsinki Games, he won the 110-meter hurdles and another relay — making him a four-time Olympic gold medalist, just like his idol, Owens. He’s the only man to win Olympic gold medals in the 100-meter dash and the 110-meter hurdles.

He returned to his hometown and spent the rest of his life there, well-known but not an icon. He spent most of his career as a manager in the business department of the Cleveland Board of Education, eventually retiring as department head in 1993. Fame never followed him very far, and he certainly never followed it.

When a reporter from The Undefeated visited him in 2016 for a story before the summer games in Rio de Janeiro, his Olympic medals were stored in a closet and there were no glory-days pictures or memorabilia on display. He was 93 years old. He didn’t consider himself a hero, but still saw Owens as one.

“He performed his athletic feat in circumstances where they were important, by throwing the lie of Aryan supremacy right in Hitler’s face and in his house,” he told The Undefeated. For himself, he said, his athletic achievements didn’t carry the same symbolism, and, at the end of the day, he didn’t think running fast was all that important in the scheme of things.

He died in 2019. He was 96.

Grit and resilience are among the qualities that make Olympic athletes great — many overcome formidable challenges just to reach the games. It’s even more difficult to survive the rigors of military service and combat to arrive at the medals podium.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 15, 2021

It’s Magic! Ye Olde Hocus Pocus

Illustration from “Hocus pocus junior : the anatomie of legerdemain.” Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

This is a guest post by Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

Looking for a few good party tricks? Perhaps pulling a card from your sleeve, or a smooth shell game, or even a captivating decapitation?

Harry Houdini had the book for you.

Page from “Hocus pocus junior: the anatomie of legerdemain.” Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

In 1927, at the bequest of Houdini, the Library received his personal collection of 4,000 volumes. In addition to documenting Houdini’s personal campaign against Spiritualism, the collection contains what you would imagine – magic books, playbills and many volumes of pamphlets on such topics as card tricks, mediums, hypnotism and handcuff escape methods. Before Houdini turned his attention to feats of escape, he rose to fame as a master of the sleight of hand. His collection carefully documents the history of that art form.

The earliest known English language work on magic, or legerdemain (as sleight of hand was then known) appeared anonymously in 1635 under the title “Hocus Pocus Junior: The Anatomie of Legerdemain.” A popular handbook of magic tricks, “Hocus Pocus” was the first illustrated book in English entirely about conjuring, and likely the first magic book written by an actual magician. UPDATE: An alert reader asks about “The Discouerie of Witchcraft,” published in 1584. That was the first book published on witchcraft, which was held as a thing apart from card tricks, slight of hand and stage tricks that constituted “magic.”

The author of “Hocus Pocus” is thought to have been William Vincent, who had a license to perform magic in England in 1619 and went by the stage name Hocus Pocus. His repertoire included dagger-swallowing and rope-dancing, as well as standard tricks of legerdemain. In addition to describing how to carry out ordinary tricks using cups and balls, the book includes a decapitation trick — “How to seeme to cut off a mans head, its is called the decollation of John Baptist.” (John the Baptist, one of the apostles of Christ, had been beheaded, an execution that loomed large in the stern Christianity of the era.)

Startling as it sounds, it’s not that complicated — the trick involves two people who greatly resemble one another (twins are ideal) and a cloth-draped table with two concealed holes in it. One person lies on their stomach on the table, their head over one hole concealed hole. The other is hidden beneath the table’s opposite end, perched beneath the second concealed hole.

During some eye-catching stage business — maybe an abracadabra wave of the wand, a puff of smoke, a twirl of the cape and perhaps a blow from a slightly misdirected ax — the first person plunges their head through the table into the first concealed hole, their neck doused with bloody-looking stuff. The second person pops their head up from the second concealed hole, also with bloody-looking stuff about the neck.

Presto! The head appears on the table, far apart from the neck, as if beheaded.

“The head may fetch a gaspe or two, and it will be better,” the author notes, then advises: “Let no body bee present while you doe this, neither when you have given entrance, permit any to be medling, nor let them tarry long.”

In other words, the stitching shows on close inspection; keep the crowd moving.

Magic aficionados will recognize this technique as the same one used in the “saw the magician’s assistant in half” trick that has been wowing audiences for ages.

Houdini, no doubt, appreciated the stagecraft and the trick’s long history.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 12, 2021

Japan in U.S. Children’s Books: “A New World”

“Japan and American Children’s Books,” by Sybille Jagusch. Published by the Library and Rutgers University Press.

As children, books are one of our first ways of experiencing the wider world. They’re often our first exposure to new and different people, places and cultures. They’re written by adults, though, so in a looking-through-the-other-end-of-the-telescope way, they also tell us a lot about the older generation that writes, illustrates and publishes them.

That’s the brilliant manner in which Sybille Jagusch, chief of the Library’s Children’s Literature Center, views the relationship between Japan and the United States in her new book, “Japan and American Children’s Books.” It’s published by Rutgers University Press in association with the Library.

The gorgeously illustrated, 385-page book is a window into both cultures as they have evolved over the past two centuries, but its focus is on the stories and illustrations that Americans have chosen to show their children about Japan. It’s not always a pretty picture, with stereotypes, caricatures and exoticism dominating the early years, but it has also resulted in beautiful stories, pictures and narratives that will last for generations.

“My intent was not to evaluate how correctly an American writer would portray American and Japanese cultures,” Jagusch said in a recent interview. “It’s to give the reader an overall picture of Japanese culture as it was portrayed by Americans. Those books today are very up to date. That was not the case in the early days, in the 19th century, because children’s books were not as highly regarded as they are today.”

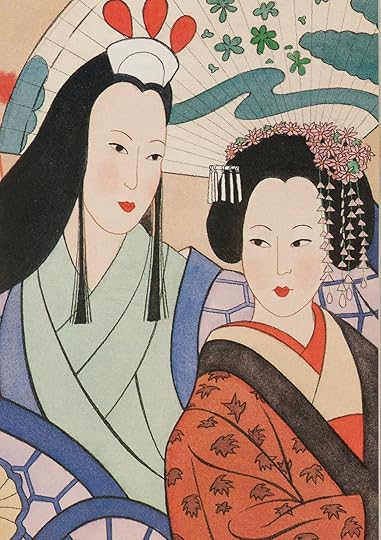

Lady Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon in “Japanese Portraits,” by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler, illustrated by Victoria Bruck, p. 13. Raintree SteckVaughn, 1994. Courtesy of Victoria Bruck Vebell.

Jagusch was appointed chief of the Children’s Literature Center in 1983. Over the ensuing years, she’s expanded the Library’s collections of rare and remarkable children’s literature, organized exhibitions and symposia and brought together an international book community. The Library now holds more than 600,000 children’s books, periodicals, maps and other items.

She became fascinated with Japan shortly after taking the helm of the Literature Center. Tayo Shima, a children’s book editor, walked into her office as a volunteer. The pair struck up a friendship and put together exhibitions and books on Japanese and American children’s books.

The papers from their first conference were published as “Window on Japan: Japanese Children’s Books and Television Today.” A companion volume, “Japanese Children’s Books at the Library of Congress: A Bibliography of Books from the Postwar Years, 1946-1985,” was also published.

Jagusch soon began traveling to Japan, touring the country, developing friendships and becoming a collector of Japanese children’s books.

This book, two decades in the making, walks readers through the history of Japan’s appearance in U.S. children’s books. As Jagusch points out, the U.S. published very few children’s books and magazines in the 18th and early 19th centuries, a time when Japan was also almost entirely closed to outsiders.

But in 1853, a gunboat trip by U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry to Edo (Tokyo) Bay resulted in a treaty that opened the nation to international trade and culture. Americans immediately saw it as a land of the exotic and told their children the same. Merry’s Museum and Parley’s Magazine, one of the few children’s magazines of the era, made a short mention of the place several years after Perry’s visit: “So wholly unknown, so strange, so curious, Japan seems like a new world, and her inhabitants like a new race of beings. It will be a long time before we shall become fully acquainted with them.”

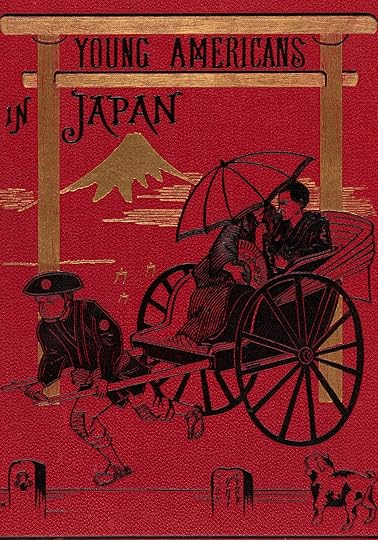

“Young Americans in Japan; or, The Adventures of the Jewett Family and Their Friend Oto Nambo,” by Edward Greey. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1882.

This approach would continue for decades, Jagusch writes. Algernon Mitford, a British diplomat and linguist, sought to correct some of most egregious errors. His research into traditional folklore, collected into “Tales of Old Japan” in 1871, included what are believed to be the first Japanese fairy tales printed in a Western language.

“These are the first tales which are put into a Japanese child’s hands; and it is with these, and such as these, that the Japanese mother hushes her little ones to sleep,” he wrote. “[t]those which I give here are the only ones which I could find in print; and if I asked the Japanese to tell me others, they only thought I was laughing at them, and changed the subject.”

The collection included magical stories in which people and animals shape-shift. There’s “The Accomplished and Lucky Tea Kettle,” which miraculously transforms itself into a badger; and “The Story of the Old Man Who Made Withered Trees to Blossom,” which begins with the man’s dog finding a pot of gold.

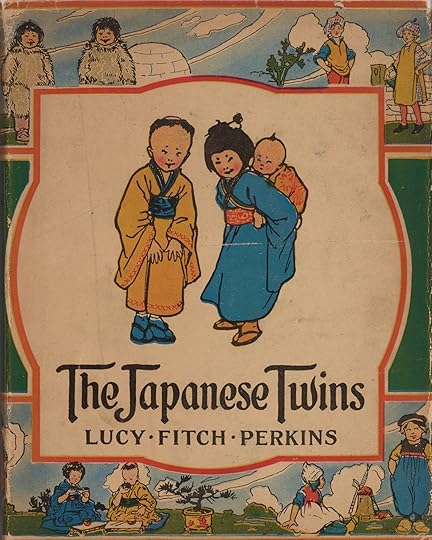

“The Japanese Twins,” written and illustrated by Lucy Fitch Perkins. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1912.

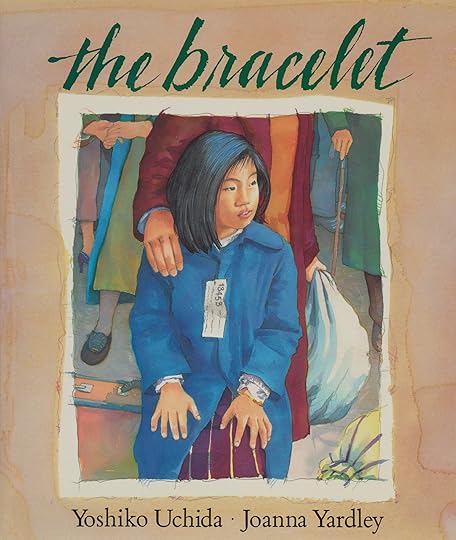

Americans seemed to cling to the idea of Japan as a realm of the mysterious until the eve of World War II. The horrors of war – the brutality of the Pacific Theater, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the internment of Japanese-Americans – were seldom reflected in children’s books of the mid-century. But, afterwards, a new realism about Japan began to appear in American children’s books, led in no small part by Japanese-American storytellers and artists who help bridge the cultural gaps. Writers such as Taro Yashima and Yoshiko Uchida created authentic and serious works, not fearing to touch subjects like the war years and the immigrant experience.

“The shift away from the exotic towards the familiar and down-to-earth is obvious, and mirrors in turn the level of increased familiarity between the two cultures,” writes J. Thomas Rimer, professor emeritus in the Department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of Pittsburgh, in the book’s introduction.

As a native German, Jagusch said she found an affinity between the two cultures and became comfortable with the idea of herself as a traveler between two worlds.

“These children’s books with their special point of view and purpose reveal the evolving relationship between Japan and America,” she writes in the book’s introductory note. “They also provide a glimpse of a traveler between these two places.”

“The Bracelet,” by Yoshiko Uchida, illustrated by Joanna Yardley. 1993. Courtesy of Joanna Yardley.

“Japan and American Children’s Books” is available in hardcover ($120.00), softcover ($49.95) and e-book ($49.95) formats from booksellers worldwide. Softcovers are available for purchase from the Library of Congress shop .

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

July 8, 2021

Researcher Story: Nelson Johnson’s “Boardwalk Empire” and “Darrow’s Nightmare”

Nelson Johnson used the Library’s collection of Clarence Darrow’s papers to inform his latest novel, “Darrow’s Nightmare.” His earlier books include “Boardwalk Empire,” which was adapted into a hit HBO series. Johnson retired in 2018 from his position as a New Jersey state superior court judge.

Nelson Johnson used the Library’s collection of Clarence Darrow’s papers to inform his latest novel, “Darrow’s Nightmare.” His earlier books include “Boardwalk Empire,” which was adapted into a hit HBO series. Johnson retired in 2018 from his position as a New Jersey state superior court judge.

You were a lawyer for decades, then a judge. Tell us about your legal career.

I grew up in a small town in southern New Jersey — and remain there 72 years later. I’m a graduate of St. John’s University and Villanova Law School.

I’ve had a very uncomplicated life. When I was 5, my grandfather said to me, “Nelson you talk so much, you should be a lawyer.” When I asked what lawyers did, he replied, “They help people when they are in trouble.” That sounded like a good thing, and as I learned more about what lawyers did, my course was charted. No uncertainty, no anxiety, no choices — becoming an attorney was all that interested me. When I was 12 or 13, my mother introduced me to “Darrow for the Defense” by Irving Stone, and Clarence Darrow became one of my heroes.

When and why did you start writing nonfiction?

I’ve been writing letters, essays and opinion pieces since my freshman year of college. In the early 1980s, I was hired to represent the Atlantic City Planning Board. I found myself in the middle of a land rush —developers were crawling all over city hall, and I was concerned about their heavy-handed influence. I also couldn’t wrap my brain around was the dysfunctionality of the place. So, I headed to the Atlantic City Free Public Library to learn more. There, I found two librarians who fed me books.

The result was “Boardwalk Empire,” which tells the story of Atlantic City’s history from the arrival of the railroad in 1854 up to the present-day era of casino gambling.

How do you select topics?

I research and write with an eye toward making sense of things on a topic no one has written about. I think that’s what all four of my books have done, namely, make sense of people, places and events that are either not understood at all, or misunderstood by commentators who got it wrong.

Besides “Boardwalk Empire” and my new book on Darrow, I’ve written about the indispensable role of African Americans in the creation of Atlantic City. And my book “Battleground New Jersey” discusses the “political dirt” that preceded New Jersey’s 1947 Constitution and creation of a genuinely independent court system.

“Darrow’s Nightmare” by Nelson Johnson.

What drew you to Darrow as a subject?

I had read Stone’s book years earlier and knew of Darrow’s problems in Los Angeles. Clarence — over wife Ruby’s advice — agreed to represent the McNamara Brothers, labor activists accused of bombing the antiunion Los Angeles Times. He learned quickly that they were guilty and negotiated a plea bargain. Not long afterward, Darrow was charged with attempting to bribe jurors who had been selected for the trial — even though it never occurred. The people of power in Los Angeles wanted to silence Darrow.

But for Earl Rogers, his extraordinarily talented defense attorney, we might never have known of Darrow. He was acquitted and went on to famously defend John Scopes in the “Scopes monkey trial” and to save Leopold and Loeb from the death penalty.

Over the years, I read many books on Darrow and was never satisfied with how his troubles in L.A. were handled by other historians.

How did Darrow’s papers inform your account?

I can’t express my excitement upon finding all of Ruby Darrow’s letters to Irving Stone in the Clarence Darrow papers at the Library. Ruby wrote to Stone and collaborated in the writing of what she hoped would be an important work in establishing Darrow as the most important lawyer in American history. In some ways, he was.

Ruby’s letters are a treasure. Frequently, I used something Ruby told Stone or a story she recounted as a thread to pull things together. Those letters are true gems, so very valuable in my research.

What was a favorite discovery?

My favorite experience was the first time I read Ruby’s letter to Stone about a surgery and hospital stay of Clarence’s in L.A. following a 1908–09 trial in Idaho, two years before his troubles in L.A. Ruby had been a reporter before marrying Clarence, and she knew how to tell a good story.

Can you comment on the importance of archival collections such as the Library’s to your work?

Primary resources are critical to my research and writing. My legal background compels me to search for documents that will support the burden of proof referred to in the law as “clear and convincing” evidence. If I can’t support a conclusion based on that standard, then I either don’t make use of those facts, or I will let the reader know that what someone said, did or suffered may or may not have occurred.

What are you working on now?

My current research is proceeding in two very different directions. I may write about 15 months in the life of Earl Rogers when he represented another lawyer and that lawyer’s client on corruption charges in San Francisco around 1908. If my research yields what I’m hoping, then I will be heading west to the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. If it doesn’t, I’m going to write a book on an aspect of slavery and its role in American history, in which case I’ll be returning to the Library.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 7, 2021

Medgar Evers: A Hero in Life and Death

Medgar Evers, 1963. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is a guest post by Jennifer Davis, a collection specialist in the Law Library’s Collection Services Division.

Medgar Wiley Evers, civil rights activist, voting rights activist and organizer, was born 96 years ago this month in tiny Decatur, Mississippi. He would go on to become one of the nation’s most significant 20th-century voices in the causes of civil rights and social justice before being assassinated at the age of 37.

His life story can be sketched out in any number of holdings at the Library, perhaps most notably in the collections of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, as he was the organization’s first field secretary in Mississippi, widely regarded at the time as the most violently racist state in the nation.

Decatur in 1925 was a town of a few hundred people in east-central section of the state. His father was a farmer and his mother a homemaker. At the time, Blacks made up about one-third of the local population but were a majority of the state population, at about 55 percent. Still, almost no Blacks could vote and none held political office. They were subject to Jim Crow segregation, lynching and state-supported violence.

When he was a teen, a friend of his father’s was lynched by a white mob for the alleged offense of insulting a white woman. On his way to school each day, Evers had to walk by the tree where the man, Willie Tingle, was hanged.

During World War II, he joined the Army and was sent to Europe to fight in France and Germany. He left the service in 1946 with the rank of sergeant.

When he returned home, he attended Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University), where he and his older brother Charles participated in civil rights activism. He met his future wife there, fellow classmate Myrlie Beasley, and married her in 1951, graduating from Alcorn in 1952.

Statue of Medgar Evers at Alcorn State University. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith. Prints & Photographs Division.

Although he took a job working as an insurance agent in the all-Black town of Mound Bayou in the Delta, he continued his activism and his interest in furthering civil rights for African Americans. While still working at his insurance job, he became president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership. In that role, he started a civil rights campaign using bumper stickers, “Don’t Buy Gas Where You Can’t Use the Restroom.”

In 1954, after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down segregation, he was the first Black person to apply to the University of Mississippi Law School, but was denied admittance because of his race. Thurgood Marshall, the future Supreme Court justice, served as his attorney.

Later that year, as a result of Evers’ activism, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People hired him as the first field secretary in Mississippi. He led investigations into nine killings of Blacks, the lynching of Emmett Till, and the wrongful conviction of Clyde Kennard. He established new NAACP chapters, particularly youth councils, organized voting registration drives, participated in boycotts, investigated and gathered evidence of “racially motivated incidents,” and promoted school desegregation. He was repeatedly sent death threats. He taught his children to crawl on the floor of their house — below the windows — and to shelter in the tub if they sensed a menacing person outside. This would prove to be well-founded advice.

In 1962, he worked on the successful bid to get James Meredith admitted to the University of Mississippi. Thousands of angry whites rioted, resulting in more than 25,000 federal troops being called into restore order. Two people were killed and more than 300 injured. The episode became a major moment in the civil rights movement.

By this point, Evers was a marked man to white supremacists. A firebomb was thrown in the family’s carport in early 1963. Myrlie Evers put out the fire with a garden hose.

Then, on June 11, 1963, Evers was at a mass meeting in Jackson, the state capital, with fellow activists. His wife and children stayed home a few miles away listening to the president’s speech on civil rights, asking Congress to create and pass civil rights legislatioṇ. Just after midnight, Evers returned home. After exiting his car, he was shot in the back with rifle fire. The gunman had been hiding in bushes across the street. When he fell, Evers was clutching a handful of T-shirts that read, “Jim Crow Must Go.”

Home of Medgar and Myrlie Evers, the day after his assassination. Photo: UPI. Prints and Photographs Division.

As a combat veteran, Evers was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery; over 3,000 people attended his funeral. Both his widow and his brother went on to long careers as notable civil rights advocates.

The assassin, Byron De La Beckwith, an avowed white supremacist, pleaded not guilty at trial in the 1960s. Then-governor Ross Barnett, himself a proud segregationist, came to the courtroom to shake Beckwith’s hand in front of the jury. Two juries, both all-white, deadlocked. But three decades later, after new evidence surfaced in stories by journalist Jerry Mitchell, a jury of blacks and whites convicted Beckwith of the shooting. He was sentenced to life in prison and died there in 2001.

Evers became more famous nationally in death than in life. His assassination, and the president’s speech, spurred action on civil rights legislation. One year later, fittingly on his birthday, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law. In 1970, the City University of New York named their new Brooklyn campus Medgar Evers College. In 2010, the U.S. Navy named an ammunition ship in his honor. And in 2017, President Barack Obama designated the couple’s home in Jackson, Mississippi, as a National Historic Landmark.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

June 30, 2021

Joy Williams Wins 2021 Prize for American Fiction

Joy Williams, wearing her trademark prescription sunglasses, accepts the 2021 Prize for American Fiction from Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. Photo: Rob Casper.

This post was co-written by Brett Zongker, chief of media relations.

Novelist, short-story and non-fiction author Joy Williams, known for works such as “State of Grace” and “The Quick and the Dead,” is the winner of the 2021 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction, Librarian Carla Hayden announced today.

The award, made annually for a lifetime of outstanding work, will be presented during this year’s National Book Festival in September.

“This is a wonderful award and one that inspires much humility,” said Williams, who now resides primarily in Arizona, but who also is known for her cross-country road trips. “The American story is wild, uncapturable and discomfiting, and our fiction — our literature — is poised to challenge and deeply change us as it becomes ever more inclusive and ecocentric.”

One of the Library’s most prestigious awards, the Prize for American Fiction honors an American author whose work is distinguished not only for its mastery of the art but also for its originality of thought and imagination. Last year’s winner was Colson Whitehead. Previous awardees have included Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo and Louise Erdrich.

“I am pleased and honored to confer this prize on Joy Williams, in celebration of her almost half-century of extraordinary work,” Hayden said. “Her work reveals the strange and unsettling grace just beneath the surface of our lives. In a story, a moment, a single sentence, it can force us to reimagine how we see ourselves, how we understand each other — and how we relate to the natural world.”

Hayden selected Williams as this year’s winner based on nominations from more than 60 distinguished literary figures, including former winners of the prize, acclaimed authors and literary critics from around the world. Williams is the author of four short story collections, two works of nonfiction and five novels, including the upcoming “Harrow.”

“Harrow,” by Joy Williams, will be published in September.

“The fiction of Joy Williams reminds me how lucky I am to be an American writer,” said Don DeLillo, winner of the 2013 prize. “She writes strong, steady and ever-unexpected narratives, word by word, sentence by sentence. This is the American language and she is an expert practitioner.”

Williams’ many honors include the Rea Award for the Short Story and the Strauss Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She was elected a member of the Academy in 2008, and she has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

“We are American writers, absorbing the American experience,” she once said at a literary conference, as quoted by the Paris Review in 2014. “We must absorb its heat, the recklessness and ruthlessness, the grotesqueries and cruelties. We must reflect the sprawl and smallness of America, its greedy optimism and dangerous sentimentality. And we must write with a pen—in Mark Twain’s phrase—warmed up in hell. We might have something then, worthy, necessary; a real literature instead of the Botox escapist lit told in the shiny prolix comedic style that has come to define us.”

She is best known for her short stories, but all of her work is populated by offbeat characters, often middle-class and on their way down, related in grim and darkly comic narratives. Her essays, particularly about the environment, are fierce and uncompromising.

Born in Massachusetts in 1944, she grew up partly in Maine, the child of a minister, and was a self-described indifferent student in high school. She went to college in Ohio, then went to the prestigious Iowa Writers Workshop. Her first short story was published when she was 22. Her first husband worked at newspapers in Florida, and she quickly became attached to the place.

Joy Williams. Photo: Courtesy of Knopf.

Here’s a hint to her personality, from that Paris Review interview:

“We rented a trailer in the middle of tangled woods on the St. Marks River. Didn’t know a soul, husband away all day. I wrote ‘State of Grace’ there [her first novel]. Excellent, practically morbid conditions for the writing of a first novel. We returned to Siesta Key, and I got a job working for the Navy at the Mote Marine Laboratory, researching shark attacks.”

Her career has since garnered the admiration of fellow writers, critics and fans of literary fiction, though she’s never been a big name on bestseller lists. Her second marriage, for 35 years, was to L. Rust Hills, the influential fiction editor at Esquire Magazine, ending only at his death in 2008. The couple had one child, Caitlin.

Williams lived in the Florida Keys for years, once writing a guidebook to the region, before moving to Arizona. She’s taught creative writing at universities from Florida to Wyoming.

She will appear at the 2021 National Book Festival, set for Sept. 17-26. The festival, with the theme “Open a Book, Open the World,” encourages attendees to create their own festival experiences through multiple formats over 10 days.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

June 28, 2021

Drag Queens! Copyright Your Work!

Female impersonators from the “An Evening With La Cage,” the Las Vegas show that ran for 23 years, closing in 2009. Photo: Carol Highsmith.

This is a guest post by Holland Gormley, a public affairs specialist in the U.S. Copyright Office. It was first published on the Copyright: Creativity at Work blog.

June is Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer (LGBTQ+) Pride Month, which is celebrated each year to honor the 1969 Stonewall Uprising in Manhattan. It’s an opportunity to recognize and celebrate the impact that this community has had on our nation’s culture and history.

One example is the art of drag performance, one of the many creative contributions to come out of the queer community. The history of drag within the copyright record runs deep, and many aspects of it are protected by copyright.

The origins of drag performances can be traced back to 1869 when Harlem’s Hamilton Lodge began hosting secret “drag balls,” which served as a safe place for the queer community to congregate without fear. These went on for decades.

In his 1940 autobiography, “The Big Sea,” Langston Hughes described Hamilton Lodge as “a queerly assorted throng on the dance floor” where men dressed as women and women dressed as men. Although the balls catered primarily to the queer community, straight artists and writers were also attracted to the celebratory atmosphere. Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, coauthors of 193e’s “The Young and Evil,” described the scene as “a […] celestial flavor and cerulean coloring no angelic painter or nectarish poet has ever conceived . . . lit up like high mass.”

Several decades later, documentaries registered for copyright protection, such as “The Queen” in 1968 and “Paris Is Burning” in 1990, explored the origins of vogueing, a precursor to modern drag. Contemporary TV series like “POSE” and “RuPaul’s Drag Race” have helped bring further awareness to the art form and draw it into more mainstream culture. It is worth underscoring how prolifically creative today’s drag queens can be. For example, “Drag Race’ contestant Brian Firkus, better known as Trixie Mattel, has recorded three albums and coauthored a book with fellow queen Katya Zamolodchikova, also known as Brian Joseph McCook.

The art of drag itself also incorporates many forms of work protected by copyright. Performers of drag can register original comedy and stand-up sketches, songs, and, possibly, certain types of choreographic works for copyright protection using a performing arts application. Videos can be registered as motion pictures, and photographs are also covered by copyright. Drag performers should consider copyright laws that apply to music used while performing choreography or during lip-synching. Some public venues will have a license that covers this use, but check to be sure.

What’s not registerable for copyright when it comes to drag? Many performers choose stage names that include clever plays on words. Although we LOVE puns at the Copyright Office, names, titles, and short phrases are not protected by copyright. The Office cannot register individual words or brief combinations of words, even if the word or short phrase is novel, distinctive, or lends itself to a play on words.

Regardless of the medium, the work inspired by and created as part of drag performance is an important part of LGBTQ+ culture. Representation of the queer community in the copyright record matters. Protecting original work through copyright helps it become a part of our diverse national record. During 2021 Pride Month, the Copyright Office celebrates the creative works of LGBTQ+ creators and performers past, present, and future. Our nation is stronger and more vibrant for it!

You can learn how to register your work for copyright protection anytime.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers