Library of Congress's Blog, page 39

November 8, 2021

Pre-Prohibition Mixology!

The bar at the Hoffman House hotel, New York, 1890, featuring the famous/scandalous painting, “Nymphs and Satyr.” H.A. Thomas & Wylie. Prints and Photographs Division.

There are several methods of carrying out social anthropology research on times past. You might conduct a study of demographic and economic charts, read newspapers of the era (paying special attention to the ads) or consult best-seller lists of books and music.

Or you might check the liquor cabinet.

This brings us to a delightfully curated selection of Library bartender manuals, “American Mixology: Recipe Books from the Pre-Prohibition Era,” put together by Alison Kelly, a reference and research specialist in the Science, Technology & Business Division. The collection is composed of 10 cocktail recipe books, from 1869 to 1911, that form a “cross-section of pre-Prohibition cocktail culture in America,” as Alison puts it. These books are available online, so if you’re of legal age, you can shake up a Champagne Cobbler or Knickerbocker Punch and party (responsibly) like it’s 1869.

Both of those drinks are from “Haney’s Steward & Barkeeper’s Manual.” While unregulated alcohol was poured down the hatch in all manners of times and places, cocktail culture was a slightly to greatly more refined art. The cocktail was the cultured drink of a sophisticate who wanted something more upscale than beer and less intoxicating that 100-proof rotgut.

“Scientific Bar-Keeping,” 1884. E.N. Cook & Co. Science, Business & Technology Division.

Ergo, the need for a top-shelf barman (almost always men at the time) to know his trade, to know how to combine alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages to create a uniquely satisfying choice. Your shelf needed wines, whiskeys, liqueurs, champagnes, cognacs, bitters, syrups, juices, jiggers, garnishes, ices, zests, mixers, modifiers, muddlers, sodas, seltzers, strainers, swizzle sticks, a shaker and — of course — a proper wardrobe. According to Haney’s, the mid-19th century bartender dressed the part: “A long white apron is almost an indispensable requisite behind a bar; and in summer time a white linen coat presents a tidy appearance.”

Others wrote for the everyman. Jacob Grohusko, author of “Jack’s Manual,” stressed that his 1908 and 1910 editions were not intended to be one of the “literary marvels,” but a handbook for the “prince of good fellows” who was mixing up, say, a good Tom Collins for his friends.

Cocktail lounges were largely gentlemen’s establishments, refined but still a bit racy. The upscale Hoffman House hotel, a New York landmark in the chromolithograph at the top of this post, was considered the unofficial headquarters of Tammany Hall politicians. William “Boss” Tweed lived at the hotel for a time. Grover Cleveland was living there when he was elected to his second term as president.

The hotel bar, meanwhile, was famously (or infamously) the home of the William-Adolphe Bouguereau painting, “Nymphs and Satyr,” which featured female nudes. It was so scandalous that people came to the bar to gawk. Hotel management graciously hung it across from a huge mirror — so patrons could catch glimpses of its reflection without having to suffer the embarrassment of being seen looking at it.

During this era, bourbon, rum and gin were the staples of the barman’s trade. Vodka and tequila were rare. Trendy drinks, most of which are now lost to time, had colorful names. You could sip shrubs, flips, smashes, toddies and dozens of punches, including those made of parsnips.

The premier drink of the post-Civil War years, according to Haney’s, was the julep, which still abides today.

“Of all the productions of the bar the julep is, without question, the chef d’ouvre (masterpiece),” wrote Haney’s. “It is essentially and originally American, and is made to perfection in the Southern States where it is universally popular.” The best of all, the publication said, was the mint julep.

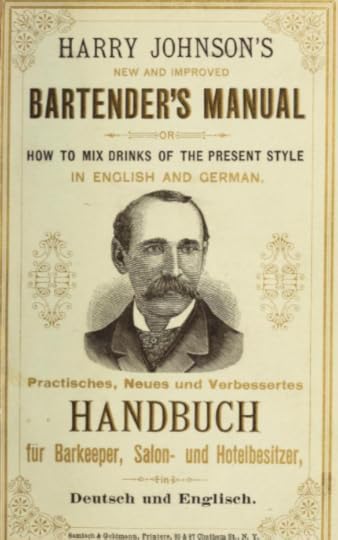

“Harry Johnson’s New and Improved Bartender’s Manual,” 1882. Science, Business & Technology Division.

Here’s Haney’s recipe:

Fill a large bar glass with thinly shaved ice, then top with a few mint sprigs and a tablespoon of white sugar. Add in 1.5 wine glasses of the “finest cognac.” Drop in a few berries (it doesn’t say what kind) and a couple of slices of orange. Shake. Add a splash of port or Jamaican rum. Sprinkle with some more sugar; garnish with more berries and another sprig of mint in the center. Serve with a straw.

Wait — a mint julep without bourbon? Is this a misprint? A bad joke?

You’ll note that this was in 1869. The first Kentucky Derby was six years later, in 1875. The Bluegrass State’s most famous product, along with racehorses, was and is bourbon. The mint julep was already a popular drink of the era, but people drank it at the Derby with homegrown bourbon instead of rum and cognac. Today, nearly 150 years later, the standard mint julep recipe is simple syrup (sugar dissolved in water) and bourbon poured over crushed ice and garnished with mint sprigs. That’s it.

That’s what we mean about cultural anthropology, seeing how the same drink (or drinks) have evolved over the decades. The Kentucky Derby became an annual cultural event across the nation and its version of the mint julep did, too.

The idea that cocktails were a self-conscious act of refinement was a daily reality of the era, too. In 1898, Joseph Haywood published “Mixology: The Art of Preparing All Kinds of Drinks.” It sold for $1. Adjusting for inflation, that’s about $30 in 2021. It was intended for the upscale set and Haywood made no bones about it. He saw cocktails as an American art form.

“…from time immemorial, men have indulged in some particular social drink, according to the custom or mannerisms of their respective countries,” he wrote in the introduction. “We, the people of these United States have more or less penchant for having our drinks mixed; hence, ‘Mixology’ … The mixologist who who concocts his beverages in a tasteful and artistic m.anner is a genuine public benefactor, providing he uses wholesome ingredients in the compounding thereof.”

More than a century later, any good bartender would agree.

[image error]New York Yacht Club cocktail lounge, circa 1901. Photo: Wurts Brothers. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 4, 2021

Native American Maps (and Ideas) that Shaped the Nation

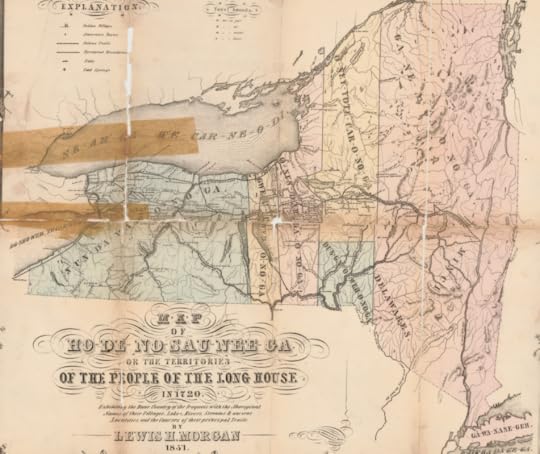

Territories of the People of the Long House in 1720. Map: Henry Louis Morgan. Geography and Map Division.

Kelly Bilz, a 2020 librarian in residence in the Geography and Map Division, wrote a short piece on this map for the Library of Congress Magazine‘s May/June issue. It’s been expanded significantly here by Jalondra Jackson, an intern in the Office of Communications.

The United States is built over the already existing identities and place names of Native Americans who lived in North America for thousands of years before European settlers arrived, a fact borne out by scanning the modern map of the nation.

From Alabama to Alaska, from Mississippi to Massachusetts, about half of all state names are taken directly or indirectly from Native American cultures and languages, including Oklahoma, Kentucky, Utah, Missouri, Michigan and North and South Dakota.

These historical fingerprints are a good thing to remember during Native American Heritage Month because, as the Library’s collections document, the influence of Native Americans on the nation’s identity goes much deeper.

Let’s take the map above as an example.

It looks like an early rendering of New York (named for the British Duke of York and Albany), but is actually the territory of the indigenous Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy or Six Nations, as it existed in 1720. The Haudenosaunee (Ho-de-no-SHOW-nee) nations had been founded on the territory of what is now New York centuries earlier.

The map’s full title is “Map of Ho-De-No-Sau-Nee-Ga: Or The Territories Of The People Of The Long House.” It shows the “names of their villages, lakes, rivers, streams & ancient localities, and the courses of their principal trails.”

Haudenosaunee is the word for the wood and bark houses that extended families, or clans, lived in. The houses mostly ranged from 80 to 120 feet long, with interior rooms connected by a central hallway. (“Iroquois” is of French origin, and not how the Haudenosaunee generally refer to themselves.)

The Long House at the Seneca Arts and Culture Center. Photo: Courtesy of Michael Galban.

The original nations of the confederacy were the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca, with the Tuscarora added later.

But it was the Haudenosaunee’s constitution, the Great Law of Peace, that proved far more influential on life in America. Benjamin Franklin, one of the nation’s Founding Fathers, was intrigued by how the Great Law balanced power among local and regional interests and among different tribes.

In the early 1750s — more than three decades before the U.S. Constitution was written — Franklin was painfully aware how united French forces routinely exploited the differences among the fledgling British Colonies. He saw in the Haudenosaunee constitution a path for his own people.

“It would be very strange,” Franklin wrote to a friend in 1751, “if six nations of ignorant savages should be capable of forming a scheme for such a union, and be able to execute it in such a manner as that it has subsisted for ages, and appears indissoluble, and yet that a like union should be impracticable for ten or a dozen colonies, to whom it is more necessary and must be more advantageous.”

Gratuitous insults aside, Franklin incorporated those ideas in his plans for a new government in the Americas; the Great Law is often cited as one of the inspirations for the Constitution’s balancing of powers.

The map, meanwhile, was made by the famed anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan. Born in 1818 in Rochester, New York, Morgan was a lawyer and state senator but is far more lastingly known as a founder of scientific anthropology.

Like Franklin, he was fascinated with the Haudenosaunee. He spent so much time with them that the largest nation among them, the Seneca, informally adopted him. While in his early 20s, Morgan founded the “Grand Order of the Iroquois,” a semi-secret fraternal society. The group would dress in Haudenosaunee regalia and chant their war cries as part of their ceremonies.

Such studies led to his first book, “The League of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois,” in 1851. The book documents the language, fabrics and a map of the nations, and is regarded as a classic in its field.

Iroquois Indians, posing for a panoramic group photo, about 1914. Photo: William A. Drennan. Prints and Photographs Division.

Morgan’s map, says Michael Galban, curator of the Seneca Arts and Culture Center in Victor, New York, was “his impression” of tribal boundaries, giving a false appearance of sharply delineated borders. Boundaries were in reality much more fluid, but Morgan’s map is acknowledged to be generally accurate, he said, even down to its trails and paths.

Today, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy still operates, maintaining their original traditions, beliefs and values through their own government — which, as Ben Franklin could tell you, had some profound ideas.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

November 2, 2021

World War II’s “Rumor Control” Project

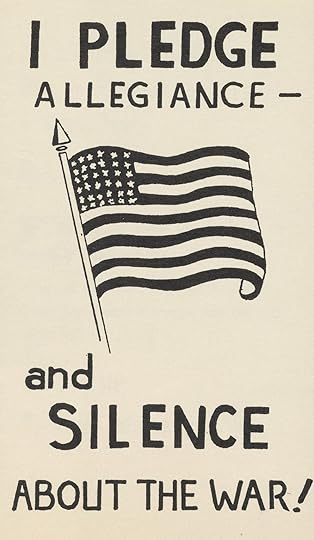

Office of War Information posters in World War II urged people not to spread rumors or to talk openly of the war effort.

In the summer of 1942, shortly after the United States entered World War II, the newly minted Office of War Information began to try to find out what people were saying about the conflict, from jokes in Georgia to conspiracy theories in California.

The “Rumor Control” campaign, now preserved in the Library’s collections, came and went with the OWI, shutting its doors in 1945 when the war was over. But, for three years, in addition to producing radio series and working with Hollywood to produce heroic films about the war effort, the OWI enlisted secret civilian “reporters” from all over the country to report what their neighbors, coworkers and fellow students were saying about the war.

In short, to spy on one another in the name of patriotism.

It targeted everyday citizens, in small towns and large. The idea was not to identify rumor spreaders by name, but capture what was buzzing around town at barber shops, dentists’ offices, classrooms and so on.

“Our democratic system will not survive the war – the President desires a socialist state,” read one reported rumor from “Seven widely scattered States.” Another: “Japanese treat Negroes as equals – this is a white man’s war. (Seven States, Southeast and Northeast.)” Others reported German submarines that had been sunk of the Florida coast, that the losses at Pearl Harbor had been much worse than had been reported, or that parachutes had been spotted in the central part of Florida and spies were now among us. And so on.

An Office of War Information worksheet sketches out the importance of identifying “rumor carriers.”

The project was taking place at an early stage of mass communications, with radio and newspapers and magazines being dominant and television just coming on the scene. Local rumors couldn’t go viral because there was no technology to make it happen, unlike today’s social media. So the OWI recruited hundreds of everyday Americans – bank workers, taxi drivers, clerks, anyone – to confidentially report what their fellow citizens were saying in private conversations. Teachers were enlisted to listen in on students.

The natural comparison would be to George Orwell’s “1984,” the dark tale of a government that monitors everything its citizens say and think and encourages its civilians to spy on one another — but that landmark book wouldn’t be written until after World War II.

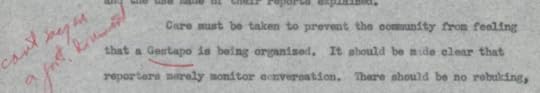

An editor’s note orders the word “Gestapo” cut from a government document.

In a document that set out the campaign’s methods and goals, organizers took a pseudo-scientific approach to identifying what constituted an actual “rumor,” like it was an odd species of fish; made pen and ink charts of “social networks” along which they spread; and recruited and trained “reporters” on how to memorize bits of conversation, going so far as to develop training skits.

Although much of the OWI’s operations were abroad — creating the same kind of disinformation to target enemy populations that they were guarding against at home — their domestic programs were controversial from the start. Lots of people in congress and people on their front porches did not like the idea of domestic government spying, no matter what it was called. Several employees resigned in a high-profile protest, and, over the years, a few others were discovered to be Soviet agents. The only significant part of the program that wasn’t shut down at war’s end was the Voice of America, which broadcasts news around the world to this day.

Some of the OWI slogans seeped into pop culture. The most famous was “Loose Lips Sink Ships,” a War Advertising Council phrase that was used on OWI posters. It became a pop-culture idiom used to urge discretion in almost any setting, often light-heartedly.

But even in the depths of war, the OWI seemed aware of the perils of a democratic nation urging citizens to report on one another, and cautioned that “care must be taken to prevent the community from feeling that a Gestapo is being organized.” An editor, red pen in hand, underlined “Gestapo” and, apparently without a sense of irony, scribbled in the margin, “can’t say in a govt. document.”

It’s a line Orwell might have penned himself.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

October 25, 2021

We’ll Miss You, Jerry Pinkney

Jerry Pinkney designed the Library’s 2005 poster for the National Book Festival..

This is a guest post by Naomi Coquillon, Chief of Informal Learning, Center for Learning, Literacy and Engagement.

Our team was left saddened by news of the passing of renowned illustrator Jerry Pinkney last week. Pinkney, whose career spanned more than 50 years, was a gifted visual storyteller with a unique style that was quickly recognizable. He garnered many awards for his work, including the Caldecott Medal for his book “The Lion and the Mouse,” which he both wrote and illustrated, and multiple Coretta Scott King awards for illustration.

Many of us at the Library grew up with his work, had the pleasure of meeting him at National Book Festival events, and have shared his work with our children. That was certainly the case for me—I recall his cover illustration for “Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry” quite vividly from my childhood and read his version of Aesop’s Fables with my six-year-old this fall. A colleague recounted the joy she felt at meeting Pinkney at her New Jersey elementary school more than 30 years ago — while we were both sitting backstage with him on September 26, less than one month ago, during the 2021 National Book Festival. There, he spoke about his most recent book, a reimagining of the story of “The Little Mermaid,” in both a live Q&A session and in conversation with author Meg Medina.

Pinkney had a long relationship with the NBF. In 2002, the second year of the festival, the Pinkney family—Jerry; his wife and frequent collaborator, Gloria; his son Brian and daughter-in-law Andrea, a children’s book illustrator and author, respectively—spoke together at the event. It was recorded and is available in two parts, here and here. In 2005, Pinkney designed the festival poster; we still receive requests for prints. You can find recordings of many of Pinkney’s appearances at the Library on our website, but I’ll include Pinkney’s short but powerful statement on his love of reading, and the value of pictorial literacy from 2016 below.

“I’m dyslexic. And so reading to me is challenging and it always has been as a kid. Yet I could also tell you that I love reading. Because I understand, one, that in many ways in order to succeed. . . you’ve got to be able to see the world. You’ve got to be able to understand others. . . I think I’m a great advocate for reading, but I also want to be an advocate for pictorial literacy. There are many ways of reading the world. “

Thank you, Jerry Pinkney.

October 21, 2021

Introducing Unfolding History: Manuscripts at the Library of Congress

Manuscript Division archivists make sense of materials that often come to them folded, bundled, stacked, or mangled. Pictured is a suitcase holding an addition to the papers of actor-director Eva Le Gallienne. It turned out to hold a letter from half-sister Hesper describing ships massing on the English coast for D-Day, and setting out for France “like ghosts in the pale light.”

The Manuscript Division is starting their own blog, as their treasure trove of documents is both (a) amazing and (b) endless. This introductory post was written by Josh Levy, a historian of science and technology in that division.

There are a lot of stories folded into the collections of the Library’s Manuscript Division, and it’s time to share them in a new way.

Those stories come from one of the world’s most extensive archives related to American history. They are found in collections that document our political, social, cultural, military, and scientific pasts. And there are a lot of collections: more than 12,000 of them, which together encompass more than 70 million items. Among them are the personal papers of presidents and artists, judges and activists, generals and poets, scientists and nurses, and transformative organizations like the NAACP and the Works Progress Administration. More are added every year.

Unfolding History: Manuscripts at the Library of Congress is a new blog that aims to offer a wider window into those collections. Here, our historians, archivists, and reference librarians will share stories about exciting new discoveries and items that catch their eye.

We’ll pull back the curtain on the whole life cycle of an archival collection, from its arrival at our doorstep – sometimes in perfect order, sometimes in a jumbled mass – to the intricate puzzle work our archivists do to make it accessible, to the evolving insights it yields as our reference librarians and historians help researchers explore it over and over again, across generations. In other words, we’ll bring you into the fold. And bring you stories we hope will spark new research ideas, find their way into your classrooms, and pause your scrolling during lunch hour.

So join us, as the Manuscript Division works to collect the unique documents, digital files, and objects that can help current and future generations probe, understand, and continually reconsider what matters about our past and present. Join us, as history unfolds.

October 19, 2021

The “Day Dream” of Billy Strayhorn’s Music

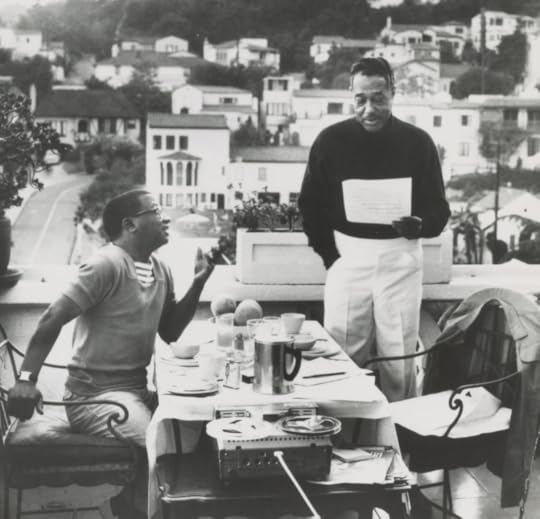

Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington. Photo: Unknown. Music Division.

It was just a few years into the 20th century. Times were impossibly hard for a young Black couple in Dayton, Ohio. Two of their three children died in infancy. So on Nov. 29, 1915, when Lillian Strayhorn gave birth to another small and sickly child, she and her husband, James, didn’t bother to name him. They didn’t think he’d live long enough. They just put “Baby Boy Strayhorn” on his birth certificate.

Eventually, though, as Duke Ellington famously put it, “his mother called him Bill.”

Billy Strayhorn’s unlikely rise from childhood sickness and poverty to becoming one of the greatest names in 20th-century American music — he was the composer, arranger and songwriter for Ellington’s orchestra for three decades — is captured in his papers at the Library. The 17,000 items, including music manuscripts, letters, photographs, scrapbooks and business contracts, were brought to the Library by his family in 2018.

Strayhorn as a child. Family photo. Music Division.

Strayhorn wrote the iconic “Lush Life,” about the darker seductions of the jazz life, when he was a teenager. He wrote “Take the ‘A’ Train” at 24, just after joining Ellington’s band. He wrote “Chelsea Bridge.” “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing.” “Day Dream.” “Rain Check.” “After All.” His style and Ellington’s so overlapped that scholars have a hard time deciding where one ended and the other began. Ellington agreed. “Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head,” he wrote in his memoir.

He was short, small, bespectacled, neatly dressed and fun to be around. He was a terrific vocal coach. Lena Horne absolutely adored him. “Ever up and onward!” was his motto. His nickname was “Sweat Pea” or “Strays.” He drank. He smoked. He was friends with everybody. He was openly gay in an era when that was all but impossible.

He died of esophageal cancer in 1967. One of his last pieces was “Blood Count,” about his cancer’s deadly progression. When he left one hospital a few weeks before his death, his nurse thanked him for his “extended hand of encouragement” to her. “I … hope that the power of God’s Blessings and protection will be your daily experience,” she wrote.

He was 51 when they buried him.

Strayhorn’s hand-written arrangement of “Day Dream.” Music Division.

His compositions are still “harmonically and structurally among the most sophisticated in jazz,” says the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, a 1,200-page reference work. Pianist Donald Shirley, remembering the man for David Hajdu’s biography, “Lush Life,” put it this way: “Many composers in jazz are good at thinking vertically and horizontally, but Billy could write diagonals and curves and circles.”

Thanks to a number of posthumous recordings, biographies and retrospectives, he is perhaps more widely known today than during his lifetime. Billy Strayhorn Songs Inc., the company his family founded in 1997, works to protect his copyrights and cement his reputation.

“The Strayhorn legacy continues to move ‘Ever Up and Onward’ … as a new generation of artists are performing his works in recordings, on television, in film and on the stage,” said A. Alyce Claerbaut, Strayhorn’s niece and president of BSSI. “There has been increasing scholar study by jazz educators that has highlighted more of the singular genius that his writing and arrangement talents contributed to the Ellington Orchestra.”

Strayhorn and his mother, Lillian Young Strayhorn at a family reunion. Early 1950s. Family photo. Music Division.

Part of the magic of the Library is holding the works of people who have changed history and helped create the modern world. Their hand pressed the pen into the paper here. They scribbled in the margin there. Time moves at the speed of their pen across the paper.

It’s that way with Strayhorn’s papers. In a working copy of “Chelsea,” the musical notation is in pencil but he marks parts for the musicians in red ink: “Paul [Gonsalves],” “Proc [clarinetist Russell Procope]” and so on. Here is “Day Dream,” taking life before your eyes. The man held this very sheet of paper, the song just an idea in his head, concentrating, his hand sketching out chord progressions, until it was there, a finished thing. A ragged copy of “Lush Life,” which got wet somewhere along the way, marks out how the lyrics should be sung: “I used to vis-it all the ver-y gay places …”

It was the era when people wrote letters, and he was delightfully chatty and offhand.

On May 18, 1952, when he was 36 and a big star, he sent his parents a postcard from Yellowstone National Park. It showed a bear, standing on two feet, looking into a car window. “Dear Mom and Pop,” he wrote, “Would you like a nice bear for your living room? Mom, I tried to call on Mother’s Day but couldn’t get through … Love and Kisses, Bill.” From Hamburg, Germany, he wrote boxer Sugar Ray Robinson, after one of his fights: “We’re a long ways from home but we heard all about you. Congratulations! See you soon, Sweet Pea.”

The collection, like his music, is a charming and lovesome thing.

“Lush Life” sheet music that was sold commercially. Music Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox

October 12, 2021

Hazel Scott: The Gorgeous Face of Jazz at the Mid-Century

Hazel Scott in an undated publicity photo from early in her career. Music Division.

Hazel Scott was the gorgeous face of jazz at the mid-century.

She was the most glamorous, well-known Black woman in America, making more than $100,000 per year, draped in custom-designed jewelry and furs. She headlined sold-out concerts, hosted her own television show and starred in Hollywood films. She wowed integrated audiences – she refused to play a segregated room – mixing jazz and classical music. “Vivacious,” newspapers liked to say.

“She has the most incandescent personality,” raved the New York Times.

Jazz, meanwhile, was the crown jewel of Black American culture, the hot, sophisticated music that was remaking popular entertainment. It sent crowds dancing. It was romance. It was swing.

That era is preserved in the Library’s jazz collections, showcasing the music’s continuing influence. There are heartbreaking letters from Chet Baker, amusing ones from Louis Armstrong. The Library holds collections of material from Ella Fitzgerald and Jelly Roll Morton and the papers of Billy Strayhorn, Charles Mingus and Max Roach. The photographs of William Gottlieb are some of the most iconic in jazz history.

Scott with her husband, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. (l), and William “Count” Basie, at the famed Birdland club in New York. Photo: Unknown. Music Division.

Scott’s story is captured in a collection of nearly 4,000 items, including music, diaries, contracts, scores, her unpublished autobiography and photographs.

Scott’s son, Adam Powell III, donated the collection to the Library in 2020, he said, so that her legacy endured in all its complexity, particularly since her stardom faded after being persecuted by the House Un-American Activities Committee during the Cold War. Besides, by the late ‘50s, Elvis was the rage, then the Beatles. Jazz was no longer center stage, and neither was Hazel Scott.

She died in 1981 of pancreatic cancer in a New York hospital. She took her last breath as Dizzy Gillespie, a friend for decades, serenaded her on a muted trumpet. She was 61.

“I’ve always wanted to do what I could to make sure that she was not lost,” Powell said. “Her intelligence and her talent and her values and her stubbornness as it were, so it could be something that was accessible to everybody.”

Scott as a child prodigy. Family photo. Music Division.

It’s a life story that reads like a Hollywood myth.

Born in Trinidad in 1920 and raised in Harlem by her mother, Alma Long Scott, a professional musician, she was a child prodigy with perfect pitch. The Julliard School of Music accepted her as a special student at the age of 8, when the minimum age for acceptance was 16.

Her mother often hosted and cooked for prominent musicians at their apartment. Scott grew up regarding Fats Waller as an uncle, Art Tatum as a de-facto dad and Billie Holiday as a big sister. Her first professional gig, at 15, was with the Count Basie orchestra. At 19, she was the star headliner at Café Society, the first integrated club in New York. In her early 20s, she’d hit the town with Leonard Bernstein on one arm and Frank Sinatra on the other. Lena Horne was a close friend. Langston Hughes mentioned her in a poem.

Her virtuosity was astonishing. She would start playing classical music, perhaps Bach or Beethoven, then slowly add syncopation and rhythm until it was swinging jazz. Then she’d launch into boogie-woogie. Her albums were hits.

She was a Hollywood film star at 23, making four films in one year, musicals like “I Dood It,” “The Heat’s On” and “Rhapsody in Blue.” She demanded the outrageous sum of $4,000 per week and got it. During the filming of “The Heat’s On,” she walked off set for three days until the wardrobe of the Black women dancers in her scene was changed from maids’ outfits to pretty floral dresses.

Scott plays piano, with Red Skelton and other cast members in a publicity still from MGM’s “I Dood It.” 1943. Photo: Unknown. Music Division.

In 1945, she married Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the Harlem congressman and pastor who was then the nation’s galvanizing civil rights leader. They made a dazzling pair, featured on magazine covers, in gossip columns and were the toasts of high-end parties in New York and Washington.

“She had every man in the room hanging on her every word,” Marjorie Lawson, a lawyer and civil rights activist who would later be D.C.’s first black female judge, told Powell biographer Wil Haygood of Scott’s first high-society appearance. “She was a sensation.”

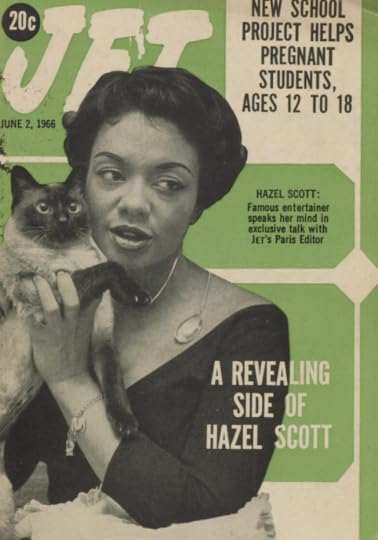

“A Revealing Side of Hazel Scott,” cover story in Jet. June 2, 1966. Music Division.

The couple were both fiercely devoted to civil rights. Conservatives accused them of being sympathetic to Communist causes during the Red Scare days of the Cold War. Scott’s name was listed in a pamphlet that attempted to smear her reputation. HUAC didn’t subpoena Scott, but she insisted on testifying before them anyway. Even her husband, who relished confrontations, urged her not to. She insisted, and, once on Capitol Hill, testified angrily. She finished by saying that musicians and artists should not be vilified by the “vicious slanders of small and petty men.”

The results were devastating.

In less than a week, her nascent television show – the first ever hosted by a Black woman — was canceled. Concert bookings dropped off. Her Hollywood career had already ended, and not just because of her stand about demeaning portrayals of Black women. Scott had called the wife of film mogul Jack Warner an epithet, she wrote in a draft of her unpublished autobiography, an incident which her son confirmed. It was one of a string of incidents over the years in which she recklessly lashed out.

Though she had made the equivalent of millions of dollars, tax brackets at the time claimed about 90 percent of it. Lawyers and accountants mismanaged much of the rest. The Internal Revenue Service said she owed far more taxes than she could pay. The Powell’s marriage crumbled, ending in divorce. She twice took overdoses of pills, but survived both suicide attempts. Stress sent her into eating binges.

Scott on a jaunt to Cannes with friends. From left: British actress and jazz singer Annie Ross, Scott, Lena Horne, Lorraine Gillespie, I.B. Lucas (Scott’s hairdresser and friend) and Dizzy Gillespie. Photo: Adam Powell III. Music Division.

She moved to Paris with their son, had a brief second marriage and, for a while, made a nice living playing in Europe. She was happy, more relaxed, hosting dinners for friends – Holiday, James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Lester Young, Quincy Jones. But times changed during the ‘60s, and after a few years, she began to struggle with paying the rent, with her health. Horne and Simone urged her to come back home.

She was just 47 when she returned to the U.S. in 1967, finding a nation caught up in riots, protests, hippies, the Vietnam War and the latter days of the civil rights movement. Young activists scarcely knew who she was. Suddenly, she seemed old-fashioned.

Her work ethic kept her going, playing intimate clubs in New York, getting a few guest roles on television series and soap operas. She settled into the role of a doting grandmother to Adam’s kids and enjoyed her friends. She poured her angry observations about being a Black woman in America, including many painful scenes in which white men had attempted to prey on her as a young star, into drafts of an autobiography that was never published.

Scott after returning to the U.S. Family photo. Music Division.

But she seemed more at peace now, more settled with how her remarkable life had evolved. The heyday of jazz might be remembered fondly, but it had been a rough way to make a living, filled with the perils of alcohol, drugs, long road trips and broken relationships. Of all the people she considered family – her mother, Tatum, Waller, Holiday – none lived past 47. It was often like that at the top of the jazz world. Clifford Brown died at 25, Bix Beiderbecke at 28, Charlie Parker at 34, John Coltrane at 40, Bud Powell at 42, Nat King Cole at 45, Bill Evans and Billy Strayhorn both at 51.

If she wasn’t at the top anymore, then so be it. She had made it through her roughest years and setbacks.

“Bitterness was not part of her package,” says Karen Chilton, Scott’s biographer. The writer/actress spent years researching “Hazel Scott: The Pioneering Journey of a Jazz Pianist from Café Society to Hollywood to HUAC.” “There may have been a sense of longing, of frustration after she came back, of ‘Where do I fit in?’ But she loved music so much, she loved jazz so much….she never stopped playing.”

She recounts Mike Wallace, the famed CBS News journalist, remembering Scott at her funeral this way: “She was gregarious. And sweet…she really lived.”

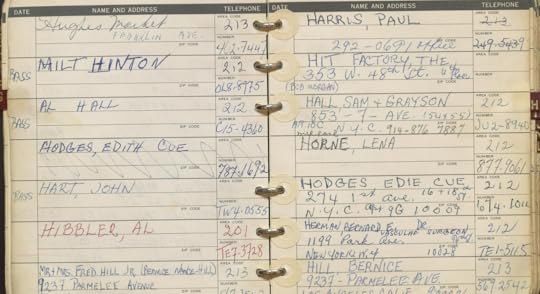

Scott’s address book lists her famous friends alongside everyday contacts. Milt Hinton, Al Hall, Al Hibbler, Paul Harris and — of course — Lena Horne were jazz stars. Sam and Grayson Hall were a television and film couple, both known for the TV classic, “Dark Shadows.” Edith Hodges was the wife of Johnny Hodges, the legendary jazz saxophonist. The Hit Factory, a famed New York recording studio, was at this location from 1975-1981. Music Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

October 8, 2021

La Biblioteca Podcast: Season 2!

“We the People Defend Dignity,” 2017. Artist: Shepard Fairey. Prints and Photographs Division. Courtesy of Shepard Fairey, Obey Giant Art.

This is a guest post by Maria Pena, a public relations strategist in the Library’s Office of Communications.

As part of Hispanic Heritage Month, the Library is launching Season 2 of La Biblioteca podcast, a six-part series titled Exploring Latinx Civil Rights in the United States, which zeros in on seminal civil rights cases and events.

The English-language series derives from A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States, created by Hermán Luis Chávez and María Guadalupe (Lupita) Partida, two Huntington Fellows in the Library’s Hispanic Reading Room. The guide offers an overview of 20th and 21st century American court cases, legislation and events that have affected the Hispanic community across the U.S., including Puerto Rico.

“I am excited by the diversity of voices and topics in this season of La Biblioteca. I learned quite a bit, and I know our listeners will come away feeling better informed,” said Suzanne Schadl, chief of the Latin American, Caribbean and European Division.

Season 2 evolves out of the resource guide — among the most viewed in the Library — and speaks with lawyers, community organizers and legislators about Latino cultural identity and history in the United States.

The first episode centers on Madrigal v. Quilligan, a 1978 federal class action lawsuit filed by 10 Mexican American women against the Los Angeles County-University of Southern California Medical Center for involuntary or forced sterilization. Although the plaintiffs lost the case in an unpublished decision from a California federal district court, the California Department of Health established new sterilization procedures and bilingual protocols for better informed consent for patients. Hermán and Lupita discuss the case and its impact with lawyer Antonia Hernández, who managed the case while working for Model Cities Center for Law and Justice.

Running through Nov. 2, subsequent weekly podcasts will discuss the fate of Central American immigrants who’ve entered the country illegally and the Temporary Protection Status, an immigration program enacted by Congress in 1990; the “Latinx” identity; Latino voter engagement; Latino student activism, and environmental activism in Puerto Rico. Guests include members of Congress, immigrant advocates, a bilingual journalist and academic experts.

La Biblioteca Podcast launched in 2017 to explore the Library’s collections. The first season, Exploring the PALABRA Archive, featured discussions with academic experts, poets and critics about a selection of recordings from the PALABRA Archive.

In addition to the Season 2 podcast, the Library joins Hispanic Heritage Month celebrations with a release of 50 new recordings from authors featured in the PALABRA Archive, including Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska and Cuban-American author, poet and anthropologist Ruth Behar. There will also be a Zoom webinar on Oct. 11 with Latin American children and young adult authors Angela Burke Kunkel, Aida Salazar and Yamile Saied Méndez.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

October 7, 2021

By the People: Transcribe Early Copyright Applications

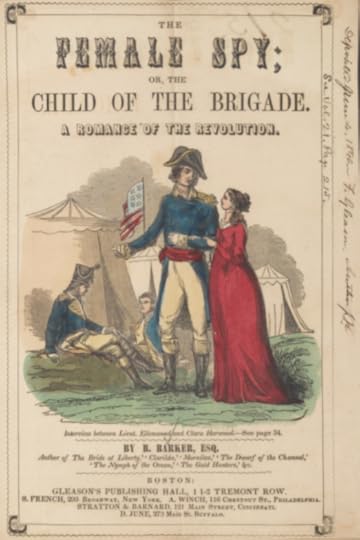

Title page copyright application for “The Female Spy,” a romance novel of 1846. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

The Library’s newest crowdsourcing campaign, American Creativity: Early Copyright Title Pages, is now online and ready for your amusement, education and transcription. It features the great (and not so great) ideas of yesteryear in copyright applications from 1790 to 1870, which recorded the young nation’s attempts to capitalize on the present and transform the future.

It’s the largest By the People crowdsourced transcription campaign so far. Previous campaigns have focused on subjects as varied as Walt Whitman, Susan B. Anthony, Rosa Parks, Civil War soldiers, baseball legend Branch Rickey and centuries of Spanish legal documents. Volunteers can read and transcribe the works or check the work of others, both steps in digitizing vast numbers of archived papers and thus making them more easily available online.

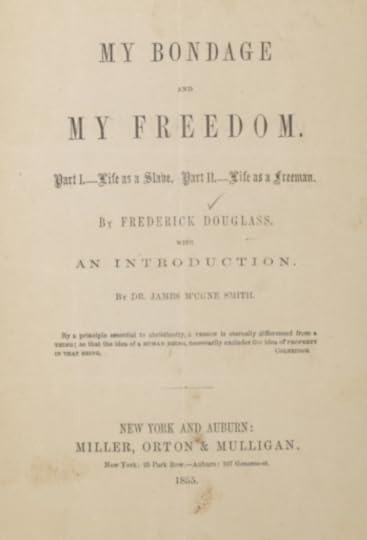

Title copyright page for “My Bondage, My Freedom,” by Frederick Douglass, 1855, six years before the Civil War began. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

In this project, the 18th- and 19th-century title pages are taken from the Early Copyright Records Collection, which we’ve recently expanded to include over 200 handwritten pre-bound ledgers that were once held by various states. From 1790 through 1870, copyright registration was accomplished by completing a form at the local federal district court, paying a fee, and depositing a printed title page with the court clerk. The Copyright Act of 1870 — the birth of modern copyright law — consolidated all these records. These early records offer a uniquely American sensibility and chronicle an industrious new nation and its intellectual pursuits. Some of the titles will be readily recognized, but many were never published or have been lost to history.

They contain some of almost every sort of intellectual activity: books, sheet music, prints, maps, dramatic compositions, advertising labels and patent drawings. There are novels, histories, plays, religious and educational instruction, music scores, science and mechanical inventions. The handwritten entries made by state court clerks often include fascinating notations, as well as pasted-in content.

“The Frog Who Would A Wooing Go,” copyright title page, 1858. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Don’t miss a lively discussion of early American copyright webinar on Thursday, Oct. 7, from 3 to 4:30 p.m. Registration is free. Speakers include John Cole, Historian at the Library of Congress; Zvi Rosen, legal scholar of copyright at the Southern Illinois University School of Law; and George Thuronyi, head of the public Information and education at Copyright Office. The recorded program will be available shortly after the live presentation.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

October 5, 2021

Thomas Jefferson’s Quran at the World Expo in Dubai

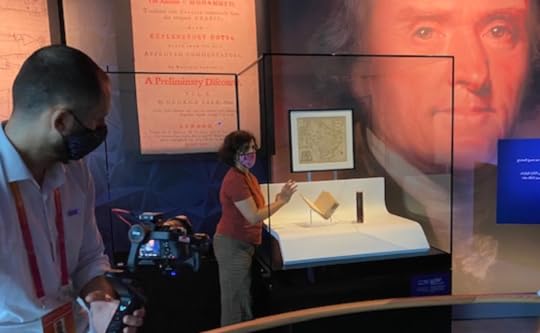

Yasmeen Khan (center), head of the Library’s Paper Conservation Section, helps install Jefferson’s copy of the Koran in the U.S. exhibit in Dubai, UAE, as USA Pavilion photographer Ibrahim Rahma films. Photo: Steve Hersch.

Thomas Jefferson’s copy of the Quran, one of the treasures of the Library, is making its first-ever appearance in the Middle East this month, debuting at the glittering World Expo in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates.

Jefferson’s English translation of the Islamic holy book is one of the stars of the Expo’s U.S. Pavilion, themed “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of the Future,” a riff on Jefferson’s famous phrase from the Declaration of Independence. Library staff installed the two-volume, 1764 copy of the Quran in a secured case as the first object on display after guests emerge from a sound and light experience that showcases the U.S. founding principles, particularly its innovations. Jefferson and the Quran are the first example of those goals, followed by some of the works of Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Graham Bell.

“Thomas Jefferson was widely interested in and curious about a variety of religious perspectives,” said Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. “Our nation’s history is a rich and beautiful reflection of the diverse ideas, cultures and religion of its citizens. The Library of Congress, the nation’s library, is a symbol to free access to information and the role it plays in a knowledge-based democracy that we share.”

The Expo, delayed for a year due to COVID-19 but still billed as Expo 2020, is a continuation of the 170-year-old tradition of international exhibitions that began as a means of sharing, if not showing off, each nation’s technology and cultural gems.

The first such event was held in London in 1851, billed as “The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations,” the brainchild of Prince Albert. He wanted to show off Britain’s industrial gains to the world (particularly Europe) as a means of building trade and British power. It was held in an iron-and-glass structure so striking that it was called the Crystal Palace.

Stereograph view of the Crystal Palace. Marian S. Carson collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

It was a magnificent success, with more than 6 million people attending, launching a plethora of such fairs through the 19th century until today. These displays were mixed with great technological wonders – nascent telephones (and mobile phones a century later), televisions, the Ferris Wheel and so on – but also, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the overt racism and colonialism of the era, as people from developing nations were often exhibited as “natives.”

The event in Dubai features exhibits from 192 nations as well as dozens of corporations and runs until next March. The Jefferson Quran will be on display for three months, an unusual stay for the type of item the Library usually only loans to other permanent museums, libraries or cultural institutions.

The book, and a framed map of Mecca that came with it, traveled in a custom-made wooden crate with four inches of padding and customized trays with more padding, along with a sensor that detects vibrations and temperature changes. Library conservation and security staffers, along with police and an international freight company that specializes in fine art shipping, secured the crate en route.

Title page of Jefferson’s copy of the Koran. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Jefferson bought his copy of the Quran in 1765 in Williamsburg, when he was 21 or 22, studying law. The two volumes are a second edition of the influential 1734 translation by George Sale, with Jefferson’s copy published in London in 1764.

Jefferson, who had an abiding interest in world religions, may have also valued the Quran as a comparison for legal codes across the world. Further, some of the enslaved Africans brought to America were Muslims, as the Library documents in the writings of Omar Ibn Said. Jefferson, who enslaved more than 600 Black people over the course of his life, may well have had firsthand experience with members of the faith.

He would go on to amass the largest collection of books in the United States in the early 19th century. After the British burned the Capitol building and the Library of Congress during the War of 1812, Jefferson sold his collection of 6,487 volumes to Congress in 1815 for $23,950. Many of his political opponents voted against the purchase, citing Jefferson’s wide-ranging interests as an “infidel philosophy” and that the books were “good, bad, and indifferent … in languages which many can not read, and most ought not.”

The Great Hall in the Thomas Jefferson Building. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The collection was so large that it took 10 wagons to carry them from his Monticello estate to Washington. It is regarded as the founding of the modern Library, and Jefferson as the Library’s patron saint, with the Library’s main building bearing his name. A fire on Christmas Eve in 1851 destroyed two-thirds of Jefferson’s collection, but the Quran was one of the volumes that survived. The book was rebound by the Library in 1918.

It endures as powerful symbol of Islamic faith in the country ̶ U.S. Rep. Keith Ellison, who in 2006 became the first Muslim elected to Congress, took his oath of office on Jefferson’s Quran.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers