Library of Congress's Blog, page 191

March 6, 2012

Lobbying for the Silver Screen

The following is a guest post by Brian Taves, senior cataloging specialist in the Library's Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

A new gift to the Library's Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division reminds us that movies are more than just the image on the screen and the sounds that accompany them. They are also the visit to the theater, and the advertising heralding the movie and the photos of scenes and stars.

"Son of the Sheik" (1926)/Library of Congress

Many of these are just as common today as they were early in the 20th century; movie posters outside of theaters remain a way to lure possible patrons into a show. Also enduring are movie stills, showing scenes from the movie or its stars, or sometimes shots of the production, most typically used in press notices accompanying reviews. Other types of advertising art have nearly vanished, however, and among the most artistic of these were lobby cards.

Lobby cards were unique for combining the graphics created to accompany a movie with still images. The advertising art was usually presented stylistically around the borders, highlighting an inset photo. While stills themselves usually measured 8×10 and were primarily in black-and-white through the 1970s, lobby cards were most often in color, measured 11×14 inches and typically issued in sets of eight.

"Heroes for Sale" (1933)/Library of Congress

This standard form allowed many variables. Usually the inset scenes showed a highlight of the movie. Sometimes, however, they emphasized portraits of stars, especially when posed to highlight the on-screen love interest. The graphics created to promote the movie could be manipulated in many different ways, and sometimes each of the cards would have unique stylization in addition to the separate scene or star image.

The fact that lobby cards were in color, at a time when most of the movies (and stills from them) were in black-and-white, established the lobby card as a distinct medium for promotion. With both the drawn poster and the photograph blended into a single work, lobby cards often achieved a unique potential. The fact that, like the stills, lobby cards were small enough to be held gave lobby cards a more intimate relationship as relics of the movie.

From 1910 through the 1980s, lobby cards were distributed to theaters along with posters, stills and advertising. Usually theater owners were instructed to return them to movie distributors, for use in subsequent screenings, or to destroy them. Thus, most lobby cards, like posters, did not long survive their original printing.

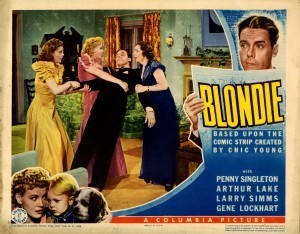

"Blondie" (1938)/Library of Congress

Lobby cards did have one advantage, however. Because of their size, they were printed on card stock rather than flimsy paper. Perhaps this, and their very colorful nature, allowed some to survive and to become a form of movie collectible.

In the 1950s, the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division began to collect lobby cards and posters and to augment its collection of stills and pressbooks (the manuals given to theater owners upon booking a film with information on promotion) through an arrangement with National Screen Service. As supplier of such advertising to many studios, National Screen Service's warehouse had become packed with items likely never to be used again for movies that had been sold to television. For three decades, until National Screen Service's demise, the Library gained a treasure trove, documenting presentations about movies to theatergoers.

"The Black Pirate" (1926)/Library of Congress

Many donations have also helped to expand the division's lobby-card holdings. Recently, noted collector Dwight Cleveland, who had previously given an extraordinary collection of glass slides used to promote upcoming movies from about 1910 to the 1950s, has given the Library several hundred lobby cards from 1910 through the 1930s. Spanning many genres and stars, the collection serves to vividly illustrate the variety and artistic potential of lobby cards as a means of promotion.

March 1, 2012

Pretty in Pink

Soon all of Washington, D.C. will be blossom-crazy thanks to the upcoming National Cherry Blossom Festival – a signature event for the capital region – set for March 20 through April 27. This year, all the stops are being pulled out as the celebration marks the 100th anniversary of the gift of trees from Tokyo to Washington.

If you haven't yet had the chance to see the blossoms, you should. The formation of trees around the Tidal Basin is quite magical. It's like walking amidst clouds of pink and white. As the petals shed, you have nature's perfect confetti.

Washington Monument, Washington, D.C., April 2, 2007. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Prints & Photographs Division.

At the annual news conference held this morning at the Newseum, organizers highlighted the bevy of festival-related programming. The morning's big announcement: Chief Horticulturalist of the National Park Service, Robert DeFeo, predicted the cherry blossoms will peak this year between March 24 and March 31. Official events include a fireworks display on April 7 and the Japanese street festival and annual parade on April 14. More information can be found at the festival's official website.

The Library of Congress is also celebrating the milestone with an exhibition titled "Sakura: Cherry Blossoms as Living Symbols of Friendship," opening on Tuesday, March 20, in the Graphic Arts Galleries on the ground floor of the Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St. S.E., Washington, D.C. The exhibition runs through Saturday, Sept. 15, 2012. More information can be found here.

Additional free events at the Library will include a series of gallery talks on the exhibition, a lecture by former Ambassador John Malott on the 1912 gift of the flowering cherry trees and an event for children, "Japanese Culture Day." Here is a full listing of the Library's related programming.

February 29, 2012

To Borrow From Google … and Rossini … and the Cosmos

What do leaping frogs and composer Gioachino Rossini have in common? Well, thanks to today's Google doodle the two are brought together rather comically – not only does today mark the cosmic anomaly of leap day but it's also the 220th birthday of Rossini … or his 53rd, depending upon which way you roll.

After some Googling of my own, it would appear the frogs – who have made previous leaping appearances in the search engine's doodle – are paying tribute to "The Barber of Seville," Rossini's famous 1816 comic opera and also one of the most-performed on stage.

The Library's own National Jukebox has pulled together more than 50 selections of Rossini's compositions, including several from the noted opera. In addition, the Library's collections include several pieces of sheet music, including this one for piano, titled "Barbier de Seville," op. 36.

Prints and Photographs Division/Library of Congress

Rossini was born on Feb. 29, 1792, in Pesaro, Italy. He has works listed as early as 1801. At 12, he delivered a set of six sonatas for strings, which scholars actually discovered the original scores in the Library of Congress following World War II. Rossini's other famous operas include "William Tell" (1829), "Semiramide" (1823) and "Cinderella" (1817). He died Nov. 13, 1868.

According to statistics, the probability of a birthday falling on leap day is 1 in 1461. To put another number on it, that means nearly 5 million people worldwide are "leapers." Now, whether they celebrate on Feb. 28 or March 1 on non-leap years is a matter of personal preference. Personally, I'd celebrate both days for double the gifts and fun! Of course, I'd likely only officially mark the event in accordance with the leap calendar … you know, to stay younger longer.

February 24, 2012

See It Now: J. Edgar, Man of Mystery

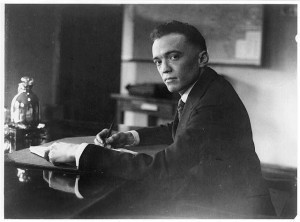

J. Edgar Hoover – former Library of Congress employee, longtime director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and a highly respected but feared individual – has been the subject of admiration and controversy alike. Some 40 years since his death, he has returned to the spotlight thanks to Clint Eastwood's biopic "J. Edgar," the DVD of which was released this month. (Although I haven't seen the DVD, one of the extra features is a "Making Of …" segment, in which Eastwood talks about Hoover working at the Library.)

In Eastwood's characterization, Hoover claims to have invented the Library's card catalog system. While not true, Hoover did become very adept at using the resource – the knowledge of which he would later use to build the FBI's own, very extensive files.

J. Edgar Hoover, Dec. 22, 1924 / National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress)

The Library had no direct input in the writing of the screenplay by Dustin Lance Black. (Within the context of the film, the scene featuring the Library implies that Hoover might have been bragging to impress his date).

According to author Kenneth D. Ackerman, separating fact from perception of the legendary American is difficult. Hoover was a hero but also had a dark side. And, of course, the rumors circulating around his personal life remain.

Ackerman spoke at the Library on Jan. 18 regarding his book "Young J. Edgar: Hoover, the Red Scare and the Assault on Civil Liberties" (Carroll & Graf, 2007). A webcast of his talk is now available on our site. Ackerman did much of his research here at the Library, using the many collections of our Manuscript and Serial and Government Publication divisions.

Regardless of the mystery and controversy surrounding Hoover, he built the FBI into a modern and professional crime-fighting organization, brought scientific investigation to the bureau, established an FBI National Academy and made the G-man brand hugely popular.

P.S. I'm hoping to make "See It Now" a more regular feature, in an effort to bring to you the various programming we host here at the Library.

February 13, 2012

Rolling Out the Welcome Mat

One would be hard-pressed not to appreciate the splendor of the Library of Congress Main Reading Room. Granted, I may have an employee bias, but it truly is a magnificent space. A local blogger once referred to it as the "Sugar Ray Robinson" of interior spaces, with grandeur that "can't be beat."

Photo by Deanna McCray-James

Twice each year, the Library opens the reading room for a special public open house. The winter open house takes place next week on the federal Washington's Birthday (Presidents' Day) holiday, Monday, Feb. 20, from 10 a.m. – 3 p.m.

More than 4,200 visitors attended last year's open house. And Library staff expect large crowds again, as this event has become increasingly popular.

James Sweany, head of the Local History and Genealogy Reading Room, talks about doing research at the Library/Photo by Deanna McCray-James

Visitors will have the opportunity to learn about the Library's genealogical collections and services, view recipes from our collection of presidential and White House cookbooks, become acquainted with the "Ask a Librarian" online reference service and check out the "Chronicling America" historic American newspaper resource, featuring president-related topic pages such as this one on Teddy Roosevelt.

A highlight of the open house is the card catalog – particularly popular with the kids, many of whom have never seen one before.

A sign of our technological times?

Visitors peruse the Library's card catalog/Photo by Deanna McCray-James

Another special treat for will be a read-aloud with Miss International, Ciji Dodds. She'll be reading "A. Lincoln and Me," by Louise W. Borden.

So grab the kids and get thee to the Library next Monday. See you soon!

February 8, 2012

Your Well-Wisher, H. C. Andersen

The following is a guest post from Taru Spiegel, reference specialist in the Library's European Division.

How would you like to receive a phone call out of the blue, asking if you are interested in a gift of priceless original letters by your favorite author? When you work at the Library of Congress, fairy-tale offers like this can come true.

Donor Barbara McKnight holds a painting of her ancestor, Louis Bagger.

For a Hans Christian Andersen fan, the Library's collection of his first editions, manuscripts, letters, presentation copies and pictorial material is a treasure trove. The collection was recently expanded with a donation of four new Andersen letters from a descendant of Louis Bagger, a 19th-century journalist, lawyer and ardent admirer of the Danish author of the classic children's stories "The Little Mermaid," "Thumbelina" and "The Ugly Duckling."

Bagger, who immigrated to the United States from Denmark in the late 1860s, helped Andersen as a translator, editor and proofreader – assistance appreciated by the author and Horace Scudder, his U.S. promoter. Hans Christian Andersen was quite popular in the U.S. and some of his stories – "The Great Sea Serpent," about the trans-Atlantic telegraph cable, for example – first appeared in the U. S. and in the English language.

The Andersen letters to Bagger span 1863 to 1872 and discuss, among other things, Andersen's fear of crossing the Atlantic, which kept the author from his admiring U.S. public; allusions to the married singer Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt, for whom Andersen held romantic feelings; and young Danish authors Andersen thought were worthy of translation into English.

Hans Christian Andersen addressed this envelope to Louis Bagger, then the editor of a Washington, D.C., newspaper called the Daily Patriot. The envelope bears Andersen's signature in the lower left corner.

Bagger also at one time entertained his own ambitions as a poet – efforts that drew a diplomatic assessment from Andersen:

Your letter and the enclosed short poems tell me that you have a warm heart and much love for poetry, but how much talent you have or do not have, I cannot possibly tell," Andersen wrote Bagger. "To put one's thoughts in verse form in our time is as easy as writing an essay. If you feel a truly intense need to compose, do it, but only when it quite overcomes you. I cannot and dare not encourage you, but neither will I discourage you. Time will disclose whether or not you have talent. — Your well-wisher, H. C. Andersen.

The letters will be housed in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

January 13, 2012

Reverberating Still

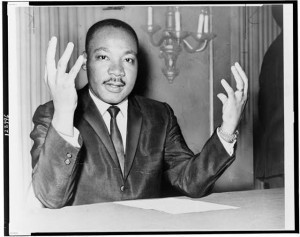

Dr. King, shortly before his trip to Norway to receive the Nobel Prize

Half a century ago, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave motion to a powerful, peaceful movement – and his words remain deeply moving today.

Here, from the Library's photographic collections, is a photo of Dr. King shortly before he traveled with members of his family to Oslo, Norway, where in December of 1964 he received the Nobel Peace Prize for his leadership in the struggle for African-Americans' civil rights.

You can find the text of his stirring acceptance speech here.

On Monday, Americans will observe Martin Luther King Day. Consider his words: "Civilization and violence are antithetical concepts … right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant … I still believe that We Shall overcome!"

Consider his words–and be moved.

December 28, 2011

The Registry — and Beyond

The closing days of the year are always exciting here at the Library of Congress, because the Librarian of Congress names the 25 films that are this year's selections to the National Film Registry, which designates films that are to be preserved for posterity due to their cultural, aesthetic and historical value.

But keep in mind, it's part of a larger preservation story that takes place every day at the Library's Packard Campus in Culpeper, Va., a state-of-the-art facility where the nation's library acquires, preserves and provides access to the world's largest and most comprehensive collection (6 million items, and counting) of films, television programs, radio broadcasts and sound recordings.

This year's picks, the culmination of a process advised by the National Film Preservation Board with extensive public input, include "Forrest Gump" (1994), "Bambi" (1942), "The Silence of the Lambs" (1991), "Stand and Deliver" (1988), "The Lost Weekend" (1945) "Porgy and Bess" (1959) and "Norma Rae" (1979). There are many other less well-known films on this year's list, but all are fascinating in one way or another – for example the home movies of Fayard and Harold Nicholas, famed dancers in the 1930s and 1940s. While documenting their stage life, they captured rare footage now unable to be found anywhere else – scenes from the interior of the Cotton Club, for example.

There are many other less well-known films on this year's list, but all are fascinating in one way or another – for example the home movies of Fayard and Harold Nicholas, famed dancers in the 1930s and 1940s. While documenting their stage life, they captured rare footage now unable to be found anywhere else – scenes from the interior of the Cotton Club, for example.

Also on this year's list is the 1921 full-length silent Charlie Chaplin classic, "The Kid," featuring a child star named Jackie Coogan later known to television audiences as Uncle Fester in TV's "The Addams Family."

There were 2,228 films nominated to the registry this year; if you want to nominate some, you are welcome to voice your opinions at the website of the National Film Preservation Board.

And heads up! This is important!

On Thursday, Dec. 29 at 10 p.m. on PBS stations' show "Independent Lens" (check local listings) an excellent documentary about the National Film Preservation Board and the registry will be aired. Titled "These Amazing Shadows," the film by Paul Mariano and Kurt Norton tells how the NFPB is saving these wonderful artworks from extinction.

If you love movies, you won't want to miss "These Amazing Shadows."

December 20, 2011

A Big Day for "Small-d"

Here at the Library of Congress, we take in more than 10,000 items a working day – books, films, music, photographs. Many are the basic stuff of everyday research; some are rare items, especially beautiful, unusual or unique; and some are major treasures of the world, to be held and preserved for the knowledge and benefit of future generations.

On October 23, 1991, we let one of those Really Big Treasures slip from our grasp – and were happy to do that, because we were sending it home in loving hands.

On that date, Vaclav Havel, then-president of Czechoslovakia (who died earlier this week) visited the U.S. Capitol to receive the 1918 first draft of the Czechoslovak Declaration of Independence, in the handwriting of the man who might be termed the Czech Thomas Jefferson — Thomas G. Masaryk, the first president of the Czechoslovak federation created at the close of World War I. In a ceremony attended by the bipartisan leaders of the U.S. House and Senate, Havel was given the document to repatriate to his country.

It had been given to the Library of Congress to keep safe in 1951 after Czechoslovakia came under Communist rule, by Masaryk's former private secretary, Jaroslav Cisar. At that time, Cisar stated that "it would, in proper time, be transferred to its final resting place in the Archives of the National Museum in Prague."

But in 1980, Cisar wrote to the Library and made an outright gift of the document, despairing of seeing his nation return to its earlier form of governance: "My hopes of seeing Masaryk's name restored to its rightful place in the official accounts of the foundation of the first formative era of our new state have, alas, proved to be overoptimistic," he said.

Cisar said he felt the document would be safer at the Library of Congress. And so it was, until the day came — following the bloodless 1989 "Velvet Revolution" that brought playwright and anti-Communist Havel to his nation's executive mansion – when it could return home safely. Havel served as president of the republic of Czechoslovakia for 2-1/2 years, and later served two terms as president of the Czech Republic that followed.

Dr. James H. Billington, the Librarian of Congress, noted that "This document … rightfully belongs to the people who have, after so many years, realized Thomas Masaryk's ambitions."

Then-House Speaker Thomas Foley noted, "Once the Library of Congress takes possession of a document, it seldom, if ever, gives it up … This is a major exception and only presented because it is a foundation document of a nation."

Havel said the care it had received at the Library of Congress "is better than it would have gotten on some shelf of the Communist Party."

"This deed is part of history," Havel said as he received the document, which he termed "the birth certificate of our nation … I cannot but be deeply moved."

Here's a webcast of a human-rights lecture Havel delivered in the Library's Coolidge Auditorium on May 24, 2005, titled "The Emperor Has No Clothes," when he was the holder of the Kluge Chair for Modern Culture at the Library's John W. Kluge Center. You can also view a discussion Havel led at the Kluge Center on Feb. 20, 2007, titled "Dissidents and Freedom."

December 16, 2011

A Stradivari Good Copy

To say that a violin made by master luthier Antonio Stradivari (1644 – Dec. 18, 1737) is priceless is an understatement. His are some of the finest stringed instruments ever made, often selling for several million dollars – that is, when they are lucky enough to be found and put on the market. Of the estimated 1,000 violins Stradivari made, there are only about 650 still in existence. The Library has three of them (and a few violas and violoncellos he also made).

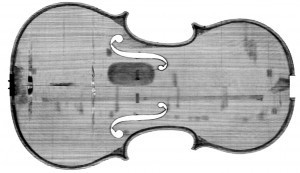

Violin by Antonio Stradivari, Cremona, 1704, "Betts" / Michael Zirkle

People have been copying these and other Stradavari instruments almost ever since they were first produced. And, while owning an original may be unattainable, thanks to some cool science, getting your hands on a pretty spot-on copy could be well within reach.

Minnesota radiologist Steven Sirr, along with violin makers John Waddle and Steve Rossow, have conceived a way to replicate a Stradivarius through CT scans. Using computed tomography (CT) imaging and advanced manufacturing techniques, they recently built a reproduction of one of the Library's Strad violins – the "Betts," dated 1704. Their goal was to "understand how the violin works" and to make reproductions available to "young musicians who can't afford an original."

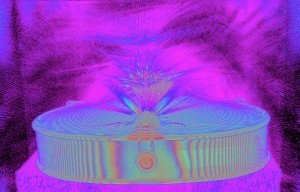

Metallic aura scan of "Betts" violin / Steven Sirr

More than 1,000 CT scan images of the "Betts" were produced and then converted to a program that instructs a machine to replicate those elements. Then, Waddle and Rossow finished, assembled and varnished the replica by hand. What resulted was an instrument with a sound quality very similar to an original Strad, according to Sirr, who is also an amateur violinist.

Scan of front detail of "Betts" violin / Steven Sirr

This isn't the first time Library strings, including the "Betts," have been scanned. Through a project with the Smithsonian Institution, Bruno Frohlich, a research anthropologist with the Museum of Natural History, has scanned nearly 50 violins and other stringed instruments – by Stradivari, his peers and today's artisans – to study their anatomy of design and hopefully uncover that elusive sound secret.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers