Library of Congress's Blog, page 186

June 29, 2012

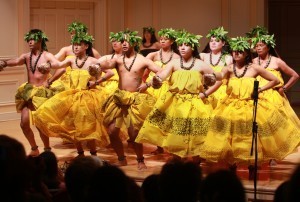

Pic of the Week: Hula Hula

When I was a kid, my dad went to Hawaii for work and brought back grass skirts and shell necklaces for me and my sister. I can remember prancing about the house mimicking what I thought at the time was a hula dance, likely influenced by watching too much “Fantasy Island.”

UNUKUPUKUPU / Abby Brack Lewis

According to the International Encyclopedia of Dance, the origins of hula are shrouded in legend. One story describes the adventures of Hi’iaka, who danced to appease her fiery sibling, the volcano goddess Pele. The Hi’iaka epic provides the basis for many present-day dances.

On Tuesday, hula dancer troupe UNUKUPUKUPU took to the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium stage to perform ancient dances and songs, rooted in the sacred `Aiha`a Pele (Ritual Dance of Volcanic Phenomena). The group is from the Hālau Hula (Hula School) of Hawaii Community College, Hilo, Hawaii. To experience the particular fiery style of hula termed `Aiha`a Pele, one is trained to call up the fire within the body and to dance until sweat shines at the temples and forehead.

The performance was featured as part of the popular “Homegrown: The Music of America” concert series presented by the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress in cooperation with the Kennedy Center Millennium Stage. The series, which is free and open to the public, brings the multicultural richness of American folk arts from around the country to the nation’s capital. Here’s a schedule of future performances.

Concerts are recorded and most are later made available on the Library of Congress website. Previous years’ concerts can be viewed here.

June 28, 2012

An Answer for Everything: 10 Years of “Ask a Librarian”

This month marks the 10th anniversary of the Ask a Librarian reference service. Through the service, users from around the world can submit online reference questions to the Library and receive responses from Library staff. On average, the reference staff receives more than 58,000 inquiries per year. In 2011, more than 62,000 inquiries were received through Ask a Librarian. Since its launch in 2002, nearly 580,000 questions have been fielded.

From the Ask a Librarian homepage, users can choose the specific area of the Library to which they’d like to submit their online inquiry. Library reading rooms also provide links to their own Ask a Librarian web forms from their home pages.

Currently three areas of the Library provide live-chat reference service: the Digital Reference Section, the Serial and Government Publications Division and the American Memory collections.

Many questions turn up repeatedly. People seeking electronic books and other electronic materials do not always understand that the Library doesn’t digitize everything – although it has more than 31 million digitized items available on its website. Many researchers want to know if the Library holds copies of every book ever published in the United States, which isn’t the case.

Users also inquire on topics ranging from art history to zoology to various presidents, as well as people seeking congressional materials of various types, such as government documents and information on government services.

Ask a Librarian also receives library and information science and digital library questions from all over America and from many other countries. In fact, in response to the volume of these questions, Library’s staff created a guide to online materials in Library Science, “Library and Information Science: A Guide to Online Resources.”

June 22, 2012

So — What Books Shaped You?

In conjunction with the Monday launch of an exhibition at the Library of Congress titled “Books That Shaped America” as part of its overarching Celebration of the Book, the Library of Congress is making public a list of 88 books by Americans that, it can be argued, shaped the nation over its lifetime.

It’s not being proposed as a definitive list, or a final list; and you are invited to comment on it, or propose alternate selections to it, at this survey link on the National Book Festival website. Variations on the list – different cuts at it — are likely in coming months and years.

There’s a lot to agree on in this list. When I sat down to ask myself what books I’d put on, I came up with a list of about 30; 26 of my choices are on the Library’s list, too. Books ranging from Paine’s “Common Sense” and Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn” to Nader’s “Unsafe at Any Speed” and Heller’s “Catch-22” – I think many of us would find common ground about books that made the ground rumble when they came out, and in some cases still move the seismometer dials.

But since we’re all being invited to name books we think ought to be on the list, but aren’t, here are a few of mine:

Ken Kesey’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” This book captured a sense many felt, in the mid-20th century, that individuals were being overwhelmed by “the machine.”

The poetry of jazz-age poet

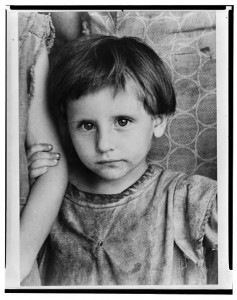

Walker Evans' portrait of Laura Minnie Lee Tengle from "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men"

Edna St. Vincent Millay (whose papers are here in the Library of Congress). Millay explored love, lust and other topics not considered suitable for a ‘lady poet,’ and gained a huge following doing it. She also tackled controversial topics, such as the Sacco & Vanzetti trial.

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ “The Yearling.” In this artful, touching coming-of-age tale, harsh reality overtakes a childhood, but family love softens the blow. Rawlings didn’t just write for kids.

As for a book that shaped me, I’d have to pick James Agee’s “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” I read it when I was 13 or so. You probably know the pictures that illustrated this book — stark black-and-white shots of farm sharecroppers and their environment taken by the now-famed photographer Walker Evans. He and Agee were sent out as a team, on a magazine assignment, to record the lives of these folk during the Depression. Agee’s eye was sharp and his prose was poetic – and his net effect on the reader, emotionally, was like having the wind knocked out of you.

Mr. Morrill Goes to Washington

On Monday (June 25) at the Library of Congress – in a conference anybody can attend, free of charge – the contributions of a congressman you’ve probably never heard of, but really should know about, will be explored.

Justin Morrill of Vermont may never be as well-known as his executive-branch supporter in these endeavors, Abraham Lincoln. (It’s probably safe to predict that you will never see a movie titled “Justin Morrill: Vampire Hunter.”) But Justin Morrill set a standard that was more than just admirable: he was the central figure in the establishment of the land-grant colleges that made higher education a reality for generations of Americans; he championed the establishment of the National Academy of Sciences; he even helped get the congressional library (yes, the Library of Congress) out of its cramped digs over in the U.S. Capitol and into its own building on Capitol Hill.

When you think about it, that combination of illuminations — higher ed, science, and access to libraries – had a lot to do with making the United States a world power.

The Librarian of Congress, James H. Billington, who will speak about Morrill at the conference, says he was a low-key congressman who didn’t hold major leadership positions or call a lot of attention to himself. His name lives on in his good works.

But what good works!

Also speaking at the conference, “Creating a Dynamic, Knowledge-Based Democracy,” will be U.S Sens. Patrick Leahy and Lamar Alexander; U.S. Rep. Rush Holt; Vartan Gregorian, president of the Carnegie Corp. of New York (which is sponsoring the event); Ralph J. Cicerone, president of the National Academy of Sciences; M. Peter McPherson, president of the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities; Anthony W. Marx, president of the New York Public Library; and Carla D. Hayden, CEO of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore.

Information about the conference, which starts at 8:30 am. in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium (10 First St. SE, Washington, DC) and will end at 3:30 p.m. and be followed by a wreath-laying ceremony at the Lincoln Memorial at 4 p.m., is here.

Come on down to the Library and indulge in a little significant history!

June 20, 2012

Legends Unplugged

On Monday, the Library of Congress announced its recent acquisition of audio interviews from of our most celebrated music icons courtesy of retired music executive Joe Smith.

More than 230 hours of recorded interviews feature the likes of Bo Diddley, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney and others discussing all manners of things, from their own personal lives to personal stories about their music.

Currently the interviews are now accessible in the Library’s Capitol Hill Recorded Sound Reference Center. Select recordings will be available on the Library’s website in the next few months.

Until then, here are a couple of snippets for your listening enjoyment from George Harrison, Mick Jagger and Dick Clark.

Mick Jagger

George Harrison

Dick Clark

June 19, 2012

Laurels for Morrill

(The following is a guest post by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library’s staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

The Library of Congress this month will celebrate the legacy of a man who helped bring higher education to millions of Americans and who played a key role in the creation of one of the nation’s most splendid pieces of architecture – the Jefferson Building.

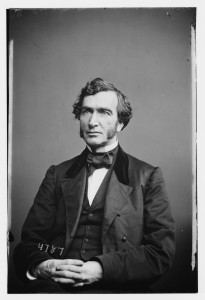

Justin Morrill

On June 25, the Library plays host to a conference that explores three events that shaped America’s knowledge-based democracy: the founding of the National Academy of Sciences, the founding of the Carnegie libraries, and the passage of the Morrill land-grant colleges act – the last the work of then-Rep. Justin S. Morrill.

The conference, which is free and open to the public, takes place in the Coolidge Auditorium and features three panel discussions and remarks by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Rep. Rush Holt (D-N.J.).

The daylong event concludes at the Lincoln Memorial with speeches and the ceremonial laying of a wreath.

“Justin Morrill was not only the longest-serving member of Congress in the first 160 years of its history, he was arguably the most important elected official in creating a nationwide infrastructure for higher education and reinforcing a knowledge-based democracy in the second half of the 19th century,” Librarian of Congress James H. Billington said.

Morrill’s legislation helped establish public universities across America following its passage in 1862 – and thus opened the door to higher education for millions of ordinary Americans.

Morrill, the son of a Vermont blacksmith, had very little formal learning himself – only the modern equivalent of an elementary-school education.

He largely was self-taught but possessed a practical and curious mind: He amassed an impressive personal library. He studied architecture on his own and designed his family home. He owned a dry-goods business and did so well that he retired comfortably at 38.

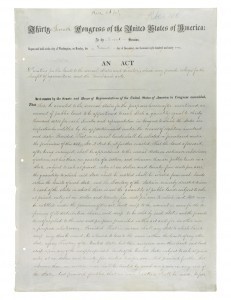

Morrill Act

In 1854, Morrill was elected to Congress, where he became a prominent figure on the House Ways and Means Committee and, later, the Senate Finance Committee – though today he remains best known for the education act that bears his name.

As a member of Congress, Morrill made himself an expert in political economy.

“The precedent he set for the protective tariffs remained U.S. policy for decades,” said Barbara Bair, a curator in the Manuscript Division.

Morrill also worked hard to promote the interests of the Library of Congress, and he personally used its resources.

An exhibition accompanying the Coolidge event includes, among other things, a register that lists books checked out by Morrill from the Library – he once received a notice from the Librarian when he failed to return “The Scarlet Letter” and the “Dictionary of Political Economy” on time.

Morrill more than made up for his tardiness: He was instrumental in getting approval from Congress for a separate building for the Library on Capitol Hill.

In 1879, Morrill strongly endorsed the plan for a separate building in a major speech before Congress.

“There’s this great quote: ‘We just don’t have enough room. We either have to move out the Congress to keep the Library here or move out the Library to keep the Congress here. You choose,’ ” Bair said, paraphrasing Morrill.

He also promoted the idea that the Jefferson Building should be much more than just a place to house books.

“The idea that it should be a showcase – that it should be brilliantly beautiful – also was not the majority viewpoint,” Bair said. “Morrill pushed that through.”

Still, Morrill mostly is remembered today for the legislation that fostered the establishment of public universities – many of which still house halls named in his honor – from coast to coast.

The Morrill Act funded the creation of such universities by granting federal land to the states to develop or sell – every state received 30,000 acres for each of its representatives and senators in Congress. These schools would teach agriculture, science and engineering as well as classical studies.

Many of the schools established as a result of the act remain major institutions – the University of California system, Cornell, Ohio State, Texas A&M, Virginia Tech and Iowa State, for example.

“Almost any college that has the word ‘state’ in it probably is a land-grant college, and some of the major research institutions that are public universities come from a land-grant tradition,” said Michelle Krowl, a curator in Manuscript.

An expansion of the act, passed in 1890, fostered the establishment or expansion of many historically black colleges – Tuskegee University, Florida A&M and Alcorn State, among others.

Part of Morrill’s interest was economic: A better-educated populace of farmers would produce more, sell more, hire more and make the country more prosperous and secure.

The act also reflected a commitment to his rural constituents.

“People tend to think about farmers as not professionals: It’s just something that people do,” Krowl said. “But with the land-grant colleges, agriculture and mechanical sciences became worthy fields of study – not something you just pick up along the way.”

Morrill also understood – through his own humble upbringing – the importance of providing opportunity for a higher education to everyone.

“On a very personal level, he really wanted to help people like himself,” Bair said. “It’s about the democratization of education.”

Congress passed the Morrill Act in 1859, but President James Buchanan vetoed it. After Southern states that opposed the plan seceded from the Union, Lincoln signed the revamped act into law in 1862.

The act made a profound impact that continued for more than a century in all corners of the country – in 1994, the act was expanded again to include Native American schools.

“Look at how many colleges benefited from the Morrill land grant and how many people graduated from those colleges: You probably have millions of people for whom college otherwise might not have been possible,” Krowl said. “You’ve got all of the discoveries that come out of the research institutions, the educational impact for Americans of diverse backgrounds – the legacy is incredible.”

June 14, 2012

Growing a Family Tree

In addition to today being Flag Day (you can read more about that here), June 14 is also Family History Day. This actually makes me think of my dad, who has become quite the budding genealogist. Over the last several months, he has been extensively researching our family tree.

Genealogical Tree. Prints and Photographs Division

Apparently one of my very distant great-grandfathers (I think ninth) on my mother’s side was Col. Richard Henry Esq., “The Immigrant” Lee (1617-1664). Among other things – he was attorney general of the Colony of Virginia, Clerk of the Quarter Court at Jamestown and at the time of his death likely the richest man in Virginia – he was the great-great-great grandfather of Confederate general Robert E. Lee and great grandfather of President Zachary Taylor.

According to my dad, we are also somehow related to Geronimo on his side, although I don’t think he’s found conclusive evidence to the fact thus far in his research.

The Library of Congress can help you grow your family tree with one of the world’s premier collections of U. S. and international genealogical and local historical publications. The Local History and Genealogy Reading Room, located in the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, is the hub for such research. More than 50,000 genealogies and 100,000 local histories comprise its collections, which are especially strong in North American, British Isles and German sources. These international strengths are further supported and enriched by the Library’s royalty, nobility and heraldry collection, making it one of only a few libraries in America that offer such resources. In addition, the vertical files in the reading room contain miscellaneous materials relating to specific family names; to the states, towns, and cities of the U.S.; and to genealogical research in general. The reading room also offers several very large CD-ROM titles produced by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Family History Library.

Reading room reference librarians also have compiled several bibliographies and guides to the Library’s genealogy collections.

The Library’s genealogy collection began as early as 1815 with the purchase of Thomas Jefferson’s library, which included such titles as the “Domesday Book,” which was the record of the survey of England made for William the Conqueror; Sir William Dugdale’s “The Baronetage of England,” a genealogical and historical account of the English Baronets up to King Henry III; and “Peerage of Ireland,” another historical and genealogical account of Ireland’s nobility.

June 8, 2012

Literate Critters

2012 National Book Festival Poster by Rafael López

When it comes to priceless art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has quite a bit, including a trove of Raphaels.

But the Library of Congress (on its National Book Festival site, now live at www.loc.gov/bookfest) has a new Rafael López National Book Festival poster for 2012 that’s priceless, too – because you can download it free of charge!

The Festival will take place Sept. 22 and 23 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It will feature more than 100 authors – appealing to all age groups – many delightful activities for kids, and a bigger, even-more-information-packed Library of Congress Pavilion.

What’s more, you can see how the poster artist took his concept from drawing to finished poster in a slideshow, available here. And you can follow his creative process on his blog.

Our Rafael doesn’t have a title yet; maybe you’d like to propose one with a comment. My nomination is “The Readers of the Rainforest.”

In Retrospect: May Blogging Edition

In addition to the Library of Congress blog that you’re reading right now, the institution has brought several other blogs into the fold. And, let me tell you, they are writing about some great things. From time to time, I hope to give a shout out to these blogs and direct your attention to what they are posting.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

The Mysterious Disappearance of the First Library of Congress

Nathan Dorn delves into the history of the Library of Congress.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

What Do You Give for a 200th Anniversary

Ellen Terrell offers a little history on Louisiana.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress

The 18th Poet Laureate delivers his swan song.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

First Year of The Signal Illustrates Value of Broad Digital Preservation Outreach

Bill LeFurgy looks back on the digital preservation blog’s first-year milestones.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Surf’s up! Jeff Bridgers talks about surfer and Olympic record-breaker Duke Kahanamoku.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Remembering Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, 1925-2012

German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is memorialized.

June 7, 2012

A Southern Stanza

( The following is a guest article about the Library’s new Poet Laureate, Natasha Trethewey, written by my colleague Mark Hartsell, which appears in the Library’s staff newsletter, the Gazette.)

Natasha Trethewey. Photo by Nancy Crampton. 2012.

The writing of Natasha Trethewey explores a past that often is unsettling – growing up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, the lives of forgotten African-American soldiers during the Civil War, the murder of her mother, the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

“When you begin to think about the past, you realize how much of it is lost to us,” says Trethewey, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Native Guard.”

On Thursday, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington announced the selection of Trethewey as the Library’s 19th poet laureate consultant in poetry.

Trethewey will open her one-year term and the Library’s annual literary season on Sept. 13 with a reading in the Coolidge Auditorium.

Trethewey succeeds Philip Levine in a position previously held by some of the most prominent American poets of the past 75 years: Robert Penn Warren, Robert Frost, Allen Tate, Robert Lowell, William Carlos Williams, Rita Dove and Gwendolyn Brooks, among many others who have served as consultant in poetry or poet laureate at the Library since 1937.

“I’m truly humbled by it. I want to be the best advocate and promoter for poetry that I can be,” says Trethewey, the author of four books of poetry – “Domestic Work,” “Bellocq’s Ophelia,” “Native Guard” and the upcoming “Thrall” – and one work of nonfiction, “Beyond Katrina: A Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.”

Trethewey, a professor of English and creative writing at Emory University, is no stranger to the Library of Congress – she researched and wrote part of “Native Guard” at the Library.

She first began conducting research at the Library in 2001 and spent all of the summer of 2004 studying Civil War letters in the reading room of the Manuscript Division.

That summer, she also worked frequently in the Main Reading Room – “a beautiful place,” she says – where she wrote many of her poems of that period.

Growing Up Down South

Trethewey was born in 1966 in Gulfport, Miss., the child of a social worker mother, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough, and a Canadian poet and professor father, Eric Trethewey.

The marriage of Gwendolyn and Eric was illegal under Mississippi law at the time – she was African-American, he was white – and they left the state to get married before going back home.

“In 1965 my parents broke two laws of Mississippi; they went to Ohio to marry, returned to Mississippi,” Trethewey wrote in “Miscegenation,” one of the poems in “Native Guard.”

Trethewey grew up biracial in the Deep South – the Gulf Coast and, later, Atlanta – in the years immediately following the civil rights movement.

“I knew at a young age that the irony of my own existence was connected to the fact that I was born 100 years to the day that Mississippi first celebrated Confederate day,” she says. “So growing up, my birthday was always Confederate Memorial Day. It helped to create this profound sense of awareness about the Civil War and the 100 years between the Civil War and the civil rights movement and my parents’ then-illegal and interracial marriage.”

She often explores that confluence of personal and cultural history in her work.

“Writers, particularly poets, always feel exiled in some way – people who don’t exactly feel at home, so they try to find a home in language. And that’s what I’ve been trying to do,” she says. “It’s important for me to assert just how much I love my native state, even as I have that kind of love-hate relationship with it.”

An ‘Unthinkable’ Event

Trethewey’s parents divorced when she was 6.

Gwendolyn moved to Atlanta, remarried and divorced again.

After that divorce, in 1985, Gwendolyn was shot and killed by her second husband – Natasha’s stepfather.

Natasha, at the time, was a student at the University of Georgia. She wasn’t really a practicing poet, just a 19-year-old trying to put her grief into words.

“I wrote a couple of poems right then to try to say the unthinkable, to deal with that tragedy – much like all the people who wrote poems after 9-11, who only turned to poetry because it seemed the only place to make sense of what happened,” she says.

But Trethewey didn’t think those poems were any good, and she hid them away.

She went on to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in English from Georgia, and, with the encouragement of her father, to write poetry seriously. She earned a master’s in poetry from Hollins University and a master’s in fine arts from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Trethewey eventually – reluctantly – found herself back in Atlanta to take the job at Emory.

“I had sworn to myself that I’d never return to this place – to Atlanta, to Decatur – where I had grown up and where the tragedy happened,” she says.

But, she ultimately figured, a good job is a good job. She found a nice home that, coincidentally, was near the courthouse in which her stepfather had been tried for, and found guilty of, the murder of her mother.

The place – and a few other things – “began to work on me a little bit,” Trethewey says.

She was approaching her 40th birthday – the age of her mother when she was murdered. She was nearing the moment when she had lived as many years without her mother as with her.

She began to write about the loss of her mother again.

“It rained the whole time we were laying her down; Rained from church to grave when we put her down,” Trethewey wrote in her poem “Graveyard Blues” from “Native Guard.”

Once more, she put away the finished poems – this time because they were so personal, not because she didn’t think they were good.

But, when editors asked her for more of her work, she reluctantly sent in these.

They ultimately ended up in “Native Guard” – and winning a Pulitzer Prize.

Trethewey plans to work in the Poetry and Literature Offices in the Jefferson Building during the second half of her term – the first time a laureate has done so since an act of Congress changed the consultant-in-poetry to poet laureate in 1986.

“It’s a place that’s close to my heart both as a poet and an academic researcher,” she says. “I want to be there because it’s a place that I felt nurtured me and my craft. I’m hoping that being there – at the seat of it all, the hub of it all – will give me a way to give back and to honor poetry.”

You can read her poem, “Domestic Work, 1937″ here.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers