Library of Congress's Blog, page 182

October 23, 2012

Black and White and (Still) Read All Over

Old newspapers have acquired an iffy reputation over the years. We bemoan the trees that had to die to bring them into existence for their one day of glory; we dub them “mullet-wrappers” or note, as they do in the British Isles, that “Yesterday’s news is tomorrow’s fish-and-chip paper.”

But old newspapers can be addictive! And if you’d like to find out just how, the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities have a little something to show you – a website called “Chronicling America,” which recently digitized its 5 millionth old-newspaper page. It features 800 newspapers from 25 states.

Short of watching a well-assembled documentary, or a movie like “The Godfather” that re-creates another place and time in great detail, there’s nothing like an old newspaper to give you a dimensional sense of a past era.

Not only can you find out what was news in that city at that time; you also see advertisements that convey everything from the fashions of the day to the nostrums people took for their ailments – including maladies like “catarrh,” “ague” and “scrofula.”

You see changes in the way people absorbed information – a newspaper published in 1912, for example, might make no effort to separate its editorial positions from its news coverage, openly lacing its news with ridicule. Legitimate news sources moved away from that in the latter part of the 20th century.

And you can see how hot topics of the day cropped up in unexpected places. Here, for example, reported in the Fayette, Missouri “Boon’s Lick Times” in 1848,

Hmmm … the spring-bottom jeans don’t seem to be in vogue this year

we find the topic of extending slavery westward raised in a letter from U.S. Sen. Thomas Hart Benton to the denizens of California, just liberated from Mexico:

“The treaty with Mexico makes you citizens of the United States; Congress has not yet passed the laws to give you the blessings of our government; and it may be some time before it does so. In the mean time … The edicts promulgated by your temporary Governors (Kearny and Mason, each an ignoramus), so far as these edicts went to change the laws of the land, are null and void …

… you are apprised that the question of extending African slavery to California occupies, at present, the attention of our Congress. I know of nothing that you can do at this time that can influence the decision of that question here. When you become a state, the entire and absolute decision of it will be in your own hands. In your present condition … I would recommend total abstinence from the agitation of the question.”

Here’s another classic old newspaper, the “Tombstone Epitaph” of Tombstone, Ariz. We all know this as the locale of the shootout at the O.K. Corral – that was in 1881 – but what was it like in Tombstone as the 20th century was rounding the corner?

This edition of the paper – March 27, 1898 – has lead stories about the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine (prelude to the Spanish-American War) and ads for such remedies as Dr. King’s New Discovery for Consumption, Ely’s Cream Balm (cures colds, hay fever, headaches and deafness!) and S.M. Barrow’s One Price Cash Store, where you could buy anything from silk and dimity fabrics and “Buckingham & Heck’s Cowboy Boots” to “guns, pistols, and cartridges.” Also, you could book a trip to the Yukon to mine for gold.

Thar’s gold in them thar yellowing pages, too. And, because Chronicling America is digital, you can dive in from your desk or home computer. No trees – no more trees, anyway — were harmed in the making of this website.

October 19, 2012

First Drafts: “The Star-Spangled Banner”

(The following is an article from the September-October 2012 issue of the Library’s new magazine, LCM, highlighting “first drafts” of important documents in American history.)

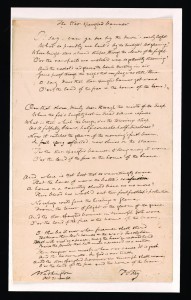

O! say, can you see by the dawn’s early light …”

Francis Scott Key autographed manuscript of “The Star Spangled Banner,” 1840. Manuscript Division.

These words are as American as, well, the American flag that inspired them.

Francis Scott Key, a young lawyer and poet, was so moved by the sight of the Stars and Stripes that he penned those very words, which became the lyrics to our country’s national anthem.

On Sept. 14, 1814, while detained aboard a British ship, Key witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry by British Royal Navy ships in the Chesapeake Bay. The failure of the British to take Baltimore during the Battle of Fort McHenry was a turning point in the War of 1812.

As dawn broke, Key was amazed to find the flag, tattered but intact, still flying above the fort. Inspired, he penned “The Defense of Fort McHenry” (later dubbed “The Star-Spangled Banner”) on the back of an envelope.

Almost immediately, his poem was published with the instruction to sing it to the music of “To Anacreon in Heaven.” Contrary to popular belief, it was not a drinking song. Written by British composer and musicologist John Stafford Smith, the tune was the beloved song of the Anacreontic Society, a London society of doctors and lawyers who were avid amateur musicians.

More than a century later, with the help and encouragement of bandleader John Philip Sousa, President Herbert Hoover signed the act establishing Key’s poem and Smith’s music as the nation’s official anthem on March 3, 1931.

The Library holds several hundred editions of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” most notably an 1840 copy of the poem in Key’s own hand. According to Loras John Schissel, a specialist in the Library’s Music Division, Key handwrote numerous copies of the poem for friends near the end of his life. The Library purchased its copy, known as the “Cist Copy,” in 1941. According to Schissel, “The Star-Spangled Banner” is the only national anthem to end in a question mark.

“Unfortunately, we don’t know what became of the back of the envelope that contained the manuscript original,” he said.

MORE INFORMATION

Bound manuscript of “The Star-Spangled Banner” (page-turner version)

Download the September-October 2012 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

October 18, 2012

Library in the News: September Edition

With the announcement of the new Library website, congress.gov (you can read more about it here and here), media outlets in September were all over the story.

The Washington Post’s Ideas & Innovations column called the site’s design a “boon” for mobile users, allowing those pages to expand or contract based on screen size.

Other high profile outlets running the story included The New York Times, Roll Call, The Hill, Politico, Associated Press, Bloomberg Business Week, UPI and The Washington Times.

On the heels of such a big announcement came one of the Library’s premier events, the National Book Festival, on Sept. 22-23. Coverage of the festival was popular on Twitter, capturing the most buzz: 84% of online volume throughout the weekend (12,614 total tweets). Facebook was the second most popular channel with 6% of online volume (850 total posts). Almost 400 news stories (print, online, radio and television) ran about the festival.

“Thousands of book lovers from around the region flocked to the Mall on Saturday for the National Book Festival, where readers who reveled in books long before they had e’s in front of them mingled happily with those who have come to love the convenience of having an entire electronic library in the palm of one’s hand,” said Washington Post reporter Lori Aratani in describing the scene.

“The future of book publishing may hang in the balance, but the need to cultivate young readers who can become the critical thinkers and book buyers of tomorrow remains constant,” wrote Jamshid Ghazi Askar for the Deseret News. “In that context, then, the kid-friendly National Book Festival occupies a unique place in the public square – different in size but similar in purpose to the thousands of school book fairs and the youth-literacy outreach efforts that take place all over the country every year.”

Children’s author Jeff Kinney of “Diary of a Wimpy Kid” books fame told USA Today, “Parents have clearly done their job with the kids here. Reading is fun!”

In other news, Poet Laureate Natasha Tretheway’s first reading at the Library on Sept. 13 inspired another round of stories and interviews with various media.

“If last night’s event at the Library of Congress is anything to go by, Natasha Trethewey’s tenure as U.S. Poet Laureate is going to be extremely popular,” wrote Washingtonian reporter Sophie Gilbert, touting the overflow audience at the event. “As she read from different poems, briefly explaining where they came from, the audience listened intently, audibly murmuring at some points when a line was particularly resonant.”

Speaking to Jeffrey Brown of PBS NewsHour, Trethewey said of her new title, “I’m hoping that my youth, relatively speaking, means I’m also energetic and can bring a lot of service to the role, rather than simply ceremonial or honorific as it certainly is.”

Debbie Siegelbaum of The Hill talked to Trethewey about her new accomplishment. “I have to tell you that when I won the Pulitzer Prize years ago, at the ceremony they said to us, ‘Now you know the first line of your obituary.’ And when I went to the Library of Congress after the call from Dr. Billington, they said to me, ‘Now you know the line that will replace that line,’” said the poet laureate.

“Her poetry is by no means stylistically consistent or even recognizable as hers except by its subjects,” said Gary Tischler of The Georgetowner. “It has the strange quality of being powerful, deceptively and often simple in its use of words and language, diverse in the method and sytle.”

And, a last little tidbit: According to the Washington Post Express in its “Explore DC” feature, the Library of Congress is “where you’ll feel guilty for not being smarter” thanks to its décor “glorifying all things knowledge-related.”

October 17, 2012

A Presidential Fundraiser

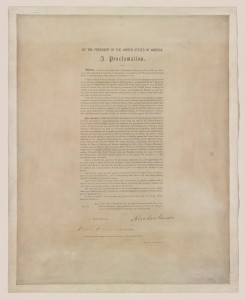

“BY THE PRESIDENT…(EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION)” Philadelphia: Leypoldt, 1864. Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress.

“That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.”

In January 1863, as the nation began its third year of a bloody war pitting its very own citizens against each other, Pres. Abraham Lincoln signed an executive order proclaiming the emancipation of slaves in Confederate territory. By issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, he created one of American history’s most iconic documents.

The Library holds a broadside edition of the proclamation – one of only 48 copies printed – signed by Lincoln, Sec. of State William H. Seward and Presidential Secretary John G. Nicolay. The document, never before on public view, will be featured in the upcoming exhibition, “The Civil War in America,” opening Nov. 12. The edition was specifically created to raise funds for the Sanitary Commission at the Great Central Sanitary Fair held in Philadelphia in June of 1864.

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private agency that held events around the country to raise money for Union soldiers. These sanitary fairs helped provide medical supplies, establish field hospitals, fund the hiring of nurses and care for wounded soldiers during and after the war. It was, in fact, a mission near and dear to Lincoln’s heart.

“The Sanitary Grand March,” by Edward Mack. Philadelphia, 1864. Music Division, Library of Congress.

President Lincoln, his wife Mary and son Tad visited the Great Central Sanitary Fair held in Philadelphia on June 16, 1864, and the day ended up being a highly lucrative fundraising effort. Admission was doubled, and more than 100,000 people flocked the grounds to see the president. Signed editions of the Emancipation Proclamation could be purchased for $10. Ultimately, the Great Central Fair raised more than $1 million for the USSC through admissions, concessions and the sales of goods and mementos like the proclamation. Of the many Northern cities that hosted major sanitary fairs between 1863 and 1865, Philadelphia was second only to New York City in money raised.

Make sure to check back next Wednesday for another spotlight on other items from “The Civil War in America.” Until then, you can read about them in previous blog posts here, here and here.

October 16, 2012

Inquiring Minds: A Visionary Center

(The Library of Congress is not solely our collections. It’s also our people. Often our blog showcases the treasures. Now we’ll also showcase the minds. The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, a program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center, to debut a new blog series, “Inquiring Minds.” We start with an introduction to the Kluge Center, an area of the Library that welcomes scholars from across the world to interact with our unique collections. )

Let’s say you want a new car. How do you decide what to buy?

Presumably, you start by doing some research. You check out the latest models available. You analyze your budget, and see what you can afford. You look in consumer magazines and websites: what are the best models selling? How much do they cost? What can I expect to spend on maintenance? You check the insurance rates where you live. You go for test drives. Soon, you have enough information to make a well-informed decision. The better informed you are, the better decision you make.

Every day we draw on information to make decisions in our lives. We become scholars, of a sort, mining the facts, analyzing and assessing the arguments, and asking how it applies to us. We take on the role of scholar to address issues that matter to us.

This notion, on a national level, is at the heart of the Library’s mission in serving Congress and the public. Thomas Jefferson wrote, “There is, in fact, no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.” (See “Like a Phoenix From the Ashes”) To make good policy, Jefferson reasoned, policy makers need information. They need conversation and thoughtful consideration of the facts. They need time and space to think. They need to draw on the knowledge of the world, and apply it to addressing our most pressing concerns.

This was also the late John Kluge’s vision. In 2000, he envisioned a space within the Library where thinkers and doers could interact. He saw the richest record of human activity and creativity ever collected, and wanted distinguished scholars and promising rising ones the opportunity to think, research, and converse with it. The result is The John W. Kluge Center.

The Kluge Center really starts with the Library’s collections, the depths of which are breathtaking. Any time you think you’ve scraped the bottom, you discover there are miles below the surface you haven’t touched. It’s not just the original printing of the Declaration of Independence or General Patton’s papers—which we have. You want a history of arguments on monogamy v. polygamy going back to the Crusades? It’s here. You want to see how the Spanish brought horses to the New World? We have a book that shows you. The extraordinary collections add to our understanding of our country’s deepest questions.

The Kluge Center provides space to scholars to mine those collections, and ruminate on their meaning. Each year, they come to tackle questions of relevance. Take our newest Distinguished Visiting Scholar, Wesley Granberg-Michaelson. From a career in the ministry, he witnessed first-hand an explosion of Christian denominations in the Global South, particularly in Africa, Asia and Latin America. More than 42,000 Christian denominations now exist. One of out every four Christians now lives in Africa. The typical Christian in the world today is a woman in Kenya. How will this impact the future of the religion?

To finish his inquiry into the impact of this new demography, he’s come to the Library of Congress. Our databases allow him to research patterns of immigration from the Global South to the Global North. Our space offers a serene environment to write and reflect. In his six weeks he will finish his book. Then he will take his research to the field to apply it.

Join the conversation. Attend one of our public events and hear from our scholars. Leave a comment below. Join us in making the The John W. Kluge Center realize its benefactor’s vision.

October 12, 2012

Centennial of Cinema Under Copyright Law

(The following is an article from the September-October 2012 issue of the Library’s new magazine, LCM, highlighting 100 years of Copyright law.)

By Wendi A. Maloney

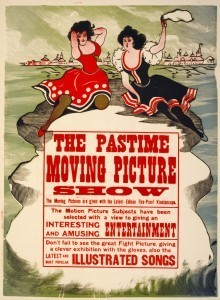

1913 poster advertising Edison's kinetoscope films. / Prints and Photographs Division

A hundred years ago, a new category of work became subject to copyright protection: motion pictures. The Townsend Amendment to the U.S. copyright law took effect Aug. 24, 1912, creating one class for dramatic motion pictures and one class for newsreels and similar material.

A May 1912 House of Representatives report explained:

The production of … motion pictures … has become a business of vast proportions. The money therein invested is so great and the property rights so valuable that the committee is of the opinion that the copyright law ought to be so amended as to give to them distinct and definite recognition and protection.”

At the urging of the movie industry, the amendment also limited statutory damages that could be awarded against movie studios for innocent infringement of nondramatic works.

The first year the Copyright Office accepted motion-picture applications, it registered 892 movies. One of the earliest was “The Charge of the Light Brigade” registered by famed inventor Thomas Edison on Sept. 26, 1912.

Edison was a prolific filmmaker whose studio produced movies on diverse topics for many years. In 1894, his firm registered “Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze,” the earliest surviving motion picture deposited with the Copyright Office. The deposit consisted of a series of still photographs printed on photographic paper.

This 1894 image consists of a series of 45 frames for Edison's kinetoscopic movie showing a man, Fred Ott, sneezing. / Prints and Photographs Division

Before inclusion of motion pictures in the copyright law, copyright owners typically registered their movies as a collection of still photographs, which the law had covered since 1865. More than 3,000 paper copies of films in that format were deposited with the Copyright Office. Many of these early films—transferred to film stock in the 1950s—are now accessible in the Library’s collections.

After 1912, copyright owners started to deposit film. Because most film at that time was made on flammable nitrate stock, the Library chose not to house it. Instead, film deposits were returned to claimants, and the Library retained only descriptive material. This practice changed in 1942 when, recognizing the importance of motion pictures to the historical record, the Library began to request the return of selected works, including films made before 1942.

Nitrate film was phased out of production in 1951, replaced by nonflammable “safety stock.” The Library’s collection of nitrate film is now substantial, thanks mostly to donations from movie studios, said Mike Mashon, head of the moving-image section of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division. Other donations have come from individual collectors and estates, including that of Edison.

As donations arrive, staff at the Library’s film-preservation laboratory in Culpeper, Va, make copies on safety stock. “We’re still acquiring nitrate films today,” Mashon said. “Gaps exist, but our collection effort has been quite successful.”

Download the September-October 2012 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

MORE INFORMATION

Learn more about Edison and his work

Visit the Motion Picture, Broadcast and Recorded Sound Division

View “Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze”

October 11, 2012

InRetrospect: September Blogging Edition

Here’s a roundup of some September selections in the Library blogosphere.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

New Dance Collections in the Performing Arts Encyclopedia (PAE)

Presentations on Bronislava Nijinska and the Ballet Russes de Serge Diaghilev are now featured in the PAE.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Yes, the Library of Congress Has Video Games: An Interview with David Gibson

David Gibson, a Moving Image technician at the Library, talks about the acquisition and preservation of games.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Caught Our Eyes: Better With Butter

Butter sculptures found in the Library’s photo collections.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

A Debut Introduction at the Festival

Poetry Center staff member Caitlin Rizzo talks about her experience at this year’s National Book Festival.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

Ellen Terrell profiles Jay Gould and James Fisk Jr.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

We Waived Death (and Survived!)

Claire Feikert-Ahalt talks about her experience in the Tough Mudder endurance challenge and the legality of death waivers.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Presidential Elections: Newspapers and Complex Text

Newspapers can be rich tools in helping students understand point of view and word choice.

October 10, 2012

Congress.gov Three-Week Check-Up

(The following is a guest post from the Library’s Director of Communications, Gayle Osterberg.)

In its first three weeks of life (still a newborn!) Congress.gov has attracted almost 45,000 visitors and is approaching a quarter million page views, as people find time to explore the new site and some of its features.

It has been terrific to see the positive response on the ease of navigation, clean layout, permanent urls and general wealth of information the site offers. Here is one of my favorites, which I can’t help but share because the Library team working on this resource is outstanding and I love when they get props: “This may be the best website redesign in the history of the world. Thank you, thank you, thank you.” A big smile, for sure.

Also coming in are lots of other comments about things users like about THOMAS and want to see incorporated into Congress.gov. The team is reading all of them.

At the time of launch, we promised additional data like the Congressional Record, past congresses and other features will be added over time – about once each quarter. Those updates are in the works. But today, the team has gone ahead with a few modest updates, several of which address some of the early suggestions we’ve received, including:

Filters have been added that intercept and recognize variants to bill citations and normalize results. For example, search results will be the same whether a user inputs hjres1, H.J. Res 1, hj1 or some other variation.

Appropriations legislation now links back to the separate appropriations listing on the THOMAS.gov site. Several comments pointed out the THOMAS site maintains detailed history for current and prior years that is useful.

A status of amendment facet has been added to the amendment tabs on the legislative and amendment detail pages so you can easily track the outcomes on a particular amendment.

Two other features have been added to help with overall education about the legislative process and about the site itself. Transcripts for all legislative process videos now include links to glossary terms. And a chronology has been added to the “About” section that will itemize new and recently added or updated features, so you can check back to see what’s new.

Finally, the point of Congress.gov is to make legislative information accessible, and the goal of this beta period is to get feedback from all kinds of users so it develops into the best site possible. To help spread the word, we posted a new promotional video today on our YouTube channel about the site (see if you recognize the voice of the narrator!). We hope you’ll share the link and encourage colleagues, educators, journalists, students, and anyone interested in following the legislative process to use it.

A Letter Home

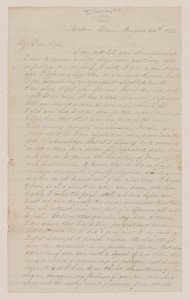

For some Union soldiers, their exposure to southern slavery profoundly altered their views on the institution, even before President Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862.

One such soldier, John P. Jones, wrote to his wife of his increasing sympathy for abolitionism after seeing the inhumanity with which slaves could be treated. He rejoiced that military policy no longer forced soldiers to return escaped slaves, which had made him feel like a “slave catcher.”

John P. Jones to his wife, August 24, 1862, Donald Benham Civil War Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

A page from his letter, sent from Medon, Tenn., and dated August 24, 1862, is a featured item in the Library’s “The Civil War in America” exhibition, opening Nov. 12. The letter has never before been seen by the public.

I am getting to be more and more of an abolitionist. I believe that this accursed institution must go down. We can never have a permanent peace as long … as this curse stains our otherwise fair insignia. The ruler of nations can never prosper these United States until it blots slavery from existence. He can no longer wink at such atrocities. This must be the grand, the final issue. I hope the powers that be will soon see it and act accordingly. It may be that we have not suffered enough yet, that the bones of a few more thousands of soldiers must bleach in the dismal swamps of the south, that a few more homes must be desolated, that suffering and desolation be more widely sown throughout the land, but come it must, postpone it as we may.

Thank God a few bright spots are luring up in the distant horizon, small it is true. But they will expand and grow brighter. We are to guard rebel property no more, and fugitives are no longer to be returned when they come within our lines. Thank God the American Soldier is no longer to be used as a slave catcher, no longer to drive helpless women around at the point of the bayonet, and be obliged to obey orders that makes him almost ashamed of being an American Soldier.”

Jones goes on to tell his “dear wife” of trips he’s made to the country since arriving in Tennessee.

The country looks wretched and forlorn. The soil is not very good, but it might be improved a great deal by good cultivation. But the people seem to have no idea of doing anything as it should be, their farming implements look as they were invented some four years before the flood. I have seen some of the most wretched looking families, some of the most abject scenes of poverty that I ever beheld.”

The identity of John P. Jones hasn’t been positively confirmed. There is a possibility that he is John P. Jones of the 45th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. According to historian Michelle Krowl of the Library’s Manuscript Division, the 45th Illinois did have a John P. Jones who enlisted in October 1861, and it also had a sergeant named Crittenden, who is mentioned in the letter. However, the description that accompanied the Library’s document suggested he was Capt. John P. Jones of Missouri, whose identity Library curators have been unable to confirm.

Jones closes his letter to his wife just as vehemently as he began:

Slavery is not only a curse to the nation but also a curse to the states, to the very plantations where it is in vogue, a curse to the owners themselves and some I have found candid enough to acknowledge it, were slavery abolished, free labor and Yankee enterprise encouraged, how soon would the south become more as the prosperous north.”

Make sure to check back next Wednesday for another spotlight on other items from “The Civil War in America.” Until then, you can read about them in previous blog posts here and here.

October 3, 2012

A Grief Like No Other

Fatalities during the Civil War were not limited to the battlefield, as both first families discovered. Both the Lincolns and the Davises lost young sons within a couple of years from each other.

The Davises lost 5-year-old Joseph in 1864 when he fell to his death from their porch in Richmond, Va. According to one account from Rice University, home to the papers of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, rumors persist older brother Jeff Jr. pushed young Joseph, but there is no evidence to support this story.

Neither parent was home at the time of the accident and apparently the adults had only just arrived as their son died. A servant discovered Joseph lying on the pavement, having fallen from a height of about 15 feet. Older sister Margaret ran to the neighbors for help, and Jeff Jr. enlisted the aid of two people passing by on the street. One of these men, a Confederate officer, wrote that Joe’s “head was contused, and I think his chest much injured internally.” Following Joseph’s death, his father refused to see visitors and could be heard pacing all night.

Another account by William C. Davis, author of “Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour,” tells a slightly different story, placing both Jefferson and wife Varina home at the time of the accident. Little Jeff found his brother’s body and told his nurse, who then ran to alert the senior Davises.

Drinking polluted water piped into the White House from the Potomac River likely caused the typhoid fever to which 11-year-old Willie Lincoln succumbed in 1862. His passing was extremely hard on his family. Of his death, his father Abraham Lincoln said, “My poor boy, he was too good for this earth. God has called him home. I know that he is much better off in heaven, but then we loved him so. It is hard, hard to have him die!”

Mary Todd Lincoln grieved so intensely for Willie that her family feared for her sanity. According to Elizabeth Keckley (or Keckly), former slave and personal confidante to the first lady, Mary was “an altered woman” and she never again went into the guest room where her son died or the Green Room where he was embalmed.

Mary Todd Lincoln to Julia Ann Sprigg, May 29, 1862, Mary Todd Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division.

A featured item in the Library’s soon-to-be-opened “The Civil War in America” exhibition is an autographed letter on mourning stationery from Mary Todd Lincoln to Mrs. John C. Sprigg, dated May 29, 1862, commenting on Willie’s death.

“Your very welcome letter was received two weeks since, and my sadness & ill health have alone prevented my replying to it. We have met with so overwhelming an affliction in the death of our beloved Willie, a being too precious for earth, that I am so completely unnerved, that I can scarcely command myself to write.”

According to historian Michelle Krowl of the Library’s Manuscript Division, the text of the Mary Todd Lincoln letter has been known to scholars for some time, but to the best of her knowledge the original letter has not been on view in a public repository until now.

“While the text is moving on its own, seeing the black mourning band around the edges of the stationery does add visual reinforcement to Mary’s words expressing her grief,” she said.

Make sure to check back next Wednesday for another spotlight on other items from “The Civil War in America,” which opens on Nov. 12. Until then, you can read a bit about them in last week’s blog post.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers