Library of Congress's Blog, page 178

February 12, 2013

A Rare Photographic Opportunity

The following is a guest post from Michelle Springer in the Office of Strategic Initiatives.

The Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith

On Presidents Day, Monday, Feb. 18, from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m, you’re invited to a special public event. Twice each year, the Library of Congress opens its magnificent Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building in Washington, D.C., for a special public open house. This is a unique opportunity to take photographs in one of the most beautiful public spaces in Washington D.C., not normally open to photographers. (Sorry, no tripods.)

In July last year as part of the Library’s Flickr Team, I had the opportunity to participate in the Library’s first Photography Meetup, where we invited photography enthusiasts to come and take pictures of the Great Hall of the Thomas Jefferson Building. Everyone had a lot of fun looking closely at all the decorative elements in the Hall, and it gave all the participants a new way to experience the beauty of this grand public space. Participants were also invited to upload their photos to Flickr with a special tag, which the Flickr team then linked to in galleries on the Library’s Flickr account.

We’re offering a similar opportunity with the Open House. Come and experience a palace of knowledge and try out your own photographic eye on the Main Reading Room. Upload your photos to your Flickr account with the tag LOCspring2013 and we’ll create galleries on the Library’s Flickr Commons account to share your images from the day.

Can’t attend? You can take an online tour of the Library through this set of photos from the Carol M. Highsmith Archive. Carol has taken more than 500 photos of the Library buildings! Her great eye will help you enjoy aerial views taken from a helicopter, close-ups ceiling murals shot from tall scaffolds, and perspective-corrected scenes of the grand interior spaces.

We look forward to seeing you there!

Learn More:

On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress,

by John Y. Cole, 1995. (original print version)

Virtual Tour of the Library of Congress buildings

History of the Library of Congress over the last 200+ years

Thomas Jefferson Building: Art and Architecture reference aid

Library of Congress photos by Carol M. Highsmith.

“LOC Itself,” a set of Carol M. Highsmith images of the Library on Flickr.

February 4, 2013

Was Richard “Rubbished?”

The wonders of modern science were used to positively identify a set of human bones found under an asphalt parking lot in England (site of a former church) as those of Richard III – a former king of England and one of Shakespeare’s most memorable villains.

The world was fascinated – it isn’t every day that a set of 500-year-old bones can yield DNA that can be cross-compared with the DNA of two of Richard’s living descendants – and the late monarch even became a trending topic on Twitter.

Actor Richard Mansfield, onstage as Shakespeare’s “Richard III”

But one question remains unanswered. Was Richard “rubbished” (the British equivalent of our informal term “trashed”) by political foes rewriting history, and their scribes, including Shakespeare?

Did Shakespeare smear him ? Was the man known for orchestrating the death-by-drowning of one foe (in a barrel of Malmsey, or Madeira wine), and prime suspect in the deaths of two young princes who could block his ascension to the throne unfairly depicted? Was he one of the great “not-nice guys” in all of British history and English lit, or not?

We may never know. But what we do know is that great actors have reveled in playing Richard III for hundreds of years – and the Library of Congress has a wonderful array of photos, illustrations and broadsides in its Prints & Photographs Division showing various actors playing the man in whose mouth Shakespeare put the phrase, “The winter of our discontent.”

Here’s one of them: Richard Mansfield, who acted in England and the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He was lionized for his Shakespeare, and was a early embracer of the works of George Bernard Shaw. Mansfield also acted early in his career in the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company, playing Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. in Gilbert & Sullivan’s ”H.M.S. Pinafore,” Major-General Stanley in “The Pirates of Penzance” and title figure John Wellington Wells in “The Sorcerer.”

Paul Wilstach’s book about Mansfield, “Richard Mansfield, The Man and the Actor,” indicates that Mansfield himself felt that Plantagenet Richard was the victim of Tudor spin, as evidenced on page 178 …

What do you think?

February 1, 2013

The Power of Poetry: Natasha Trethewey Comes to the Library

The following is a guest post from the Library’s Director of Communications, Gayle Osterberg.

Chris Wallace of Fox News interviews Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry Natasha Trethewey in the Poetry Room of the Library’s Poetry and Literature Center. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis

It has been a busy first two weeks for the Poet Laureate, Natasha Trethewey, who is working this spring from the Library of Congress Poetry and Literature Center – a first for a laureate.

She visited with fellow poet Richard Blanco about his poem “One Today”, which he read at Barack Obama’s second presidential inauguration. She appeared on NPR’s Diane Rehm Show. She met with Mississippi Senator Thad Cochran. And she was profiled beautifully by the Washingtonian’s Sophie Gilbert in the new February issue.

Then on Wednesday, her first reading of the year drew a standing-room-only audience of several hundred to hear her read from “Native Guard”, her Pulitzer Prize-winning collection that she researched and wrote here at the Library. The Washington Post’s Ron Charles describes it here.

It is no wonder Chris Wallace and the Fox News Sunday team decided to spotlight Natasha as this week’s Power Player of the Week. She will be featured on this Sunday’s program, and I hope you and thousands nationwide have a chance to watch her and hear her talk about poetry and its importance as an elegant form of communication that touches the heart as well as the intellect.

She was asked at Wednesday’s reading what her top three priorities are for her laureateship and she replied to applause, “Bring poetry to a wider audience, bring poetry to a wider audience, bring poetry to a wider audience.” I think it is fair to say even after a few days she will absolutely meet those goals.

January 30, 2013

Library Signs “Declaration of Learning”

Today, the Library of Congress joined 12 other government agencies and non-governmental organizations in signing a “Declaration of Learning” that formally announces their partnership as members of the Inter-Agency Collaboration on Education. The initiative is spearheaded by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton, who joined representatives at the signing ceremony in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms at the U.S. Department of State. The historic Treaty of Paris desk was used to complete the signing.

Through this partnership, the Library has committed to working together with the other agencies and organizations in utilizing historic artifacts in its collections, as well as its educational expertise, to create digital learning tools that can be accessed from computers, tablets and cell phones. Non-digital learning tools will also be created for classroom and public use.

Now students, teachers and life-long learners will have the opportunity to explore historic objects and access new learning resources digitally, helping to ensure that tomorrow’s leaders better understand the events, ideas and movements that have shaped our country and the world. The group has selected “Diplomacy” as the first topic around which learning resources will be created. A new topic will be selected every two years.

Other institutions participating in the the Inter-Agency Collaboration on Education and signing the Declaration of Learning include the National Archives, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institutions, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Endowment for the Arts, Newseum, American Library Association, National Center for Literacy Education, National Council of Teachers of English, National Council for the Social Studies and the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

More information can be found at the U.S. Department of State website.

January 29, 2013

First Drafts: Poem for a President

(The following is an article from the January-February 2013 issue of the Library’s magazine, LCM, highlighting “first drafts” of important documents in American history.)

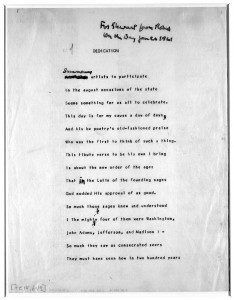

This typescript of Robert Frost’s poem “Dedication” contains Frost’s holograph script corrections in ink and Stewart Udall’s holograph printed clarifications in pencil on the last page. Stewart L. Udall Papers, Manuscript Division

Robert Frost (1874 –1963) was the first poet commissioned to write a poem for a presidential inauguration. His poem, titled “Dedication,” was intended to be read at the inauguration of John F. Kennedy Jr., but the sun’s glare on the snowy January day prevented the poet from reading his most recent work. Instead, he recited “The Gift Outright” from memory. Later that day, Steward L. Udall, Kennedy’s Secretary of the Interior, asked Frost for the original manuscript of the unread new poem. Frost agreed and added the inscription: “For Stewart from Robert on the day, Jan. 20, 1961.” The manuscript came to the Library of Congress when Udall donated his papers in 1969.

Robert Frost served as the Library’s Consultant in Poetry from 1958 to 1959. He recorded readings of his poetry in 1948, 1953 and 1959 for the Library’s Archive of Recorded Poetry and Literature.

Frost’s reading at the Kennedy inaugural was selected for inclusion on the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress in 2003.

MORE INFORMATION

Guide to online resources on Robert Frost

Download the January-February 2013 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

January 24, 2013

Inquiring Minds: An Interview with Kluge Fellow Lindsay Tuggle

The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center.

Lindsay Tuggle

Lindsay Tuggle, Ph.D., teaches English Literary Studies at the University of Sydney, Australia. Her dissertation dealt with mourning and ecology in the work of Walt Whitman. As a Kluge Fellow, she has been researching and writing her first book, “The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America.” She lectures on the topic today at noon in the Woodrow Wilson room (LJ-113).

Q: Tell us about your research.

A: I’m at the Library of Congress researching and writing my book, “The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America.” The book explores the shrinking distinction between the body as object of mourning and subject of scientific enquiry throughout the 19th century.

Q: Your lecture explores Walt Whitman and Union surgeon John Brinton. What is the connection between the two and the larger story of death in the Civil War?

A: Whitman and surgeon John H. Brinton, founding curator of the Army Medical Museum, led parallel lives during the war. Both arrived at Falmouth, Va., in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Fredericksburg. Both frequented the Washington hospitals. Whitman spent the majority of his waking hours caring for wounded soldiers. Brinton recruited hospital surgeons to submit examples of unusual injuries and amputations.

On August 1, 1862, Brinton was directed to establish the Army Medical Museum. This was the beginning of an anatomical collection that would incorporate thousands of Civil War remains, many of which are still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine. The preservation of the body became of paramount importance during the Civil War. While the practice of embalming would have been repulsive to many antebellum mourners, the war altered this perception, due to the collective desire to prolong the visibility of fallen soldiers. This corpse fever was reflected in the popularity of mourning manuals, elegies, séances and posthumous portraiture. The Civil War ushered in an era of national mourning that centered around the memorialisation of bodies en masse.

Q: How did you get interested in Walt Whitman’s perspectives on the dead?

A: Although I live in Australia, I grew up in Alabama and Kentucky, both states where the scars of the Civil War remain unhealed. I’ve always been fascinated by that bloody chapter in our history.

The idea for the book arrived because I wanted to understand how Walt Whitman came to an understanding of the corporeal afterlife so far removed from his initial anxiety in the face of posthumous wounds. What catalyzed this transformation, and how did it respond to cultural changes in medical, mourning and burial practices? “The Afterlives of Specimens” establishes Whitman’s role in evolving cultural understandings of the body as an object of posthumous discovery and desire.

Q: You’ve discovered some rare treasures in the Library’s collection. Tell us about them.

A: I’ve uncovered correspondence between Whitman and Army Medical Museum staff in the post-war years. This evidence of a direct connection between Whitman and the museum is invaluable to my work. I’m especially excited about two items that I found in the Thomas Harned Whitman Collection. One is an untitled draft poem that Whitman composed about his observation of an amputation in a Civil War hospital. The other, which I was most thrilled to discover, is a fragment of an unpublished poem about skeletal human remains that almost certainly relates to specimens at the Army Medical Museum. I will be discussing both of these poems in my lecture on January 24.

Lindsay Tuggle lectures today, Jan. 24, at noon — one of many Library of Congress programs in conjunction with the Library’s acclaimed exhibit “The Civil War in America.” Learn more on the exhibit homepage.

January 21, 2013

Presidential Precedents

The Library of Congress holds the papers of 23 U.S. presidents, from George Washington to Calvin Coolidge. These collections, housed in the Manuscript Division—and the Library’s holdings in other formats such as rare books, photographs, films, sound recordings, sheet music and maps—inform us about the time and tenor of each of their administrations.

Unique to each president were the circumstances surrounding his inauguration. One was the first to hold the office. Others were elected to the office during trying times in the nation’s history. Some of those elected to office reflected a major shift in the nature of the electorate. Still others were thrust into the role by the deaths of their predecessors. Following many of the precedents set by the first president—with some variations on the theme introduced by those who followed—the presidential inauguration remains a pivotal event.

The following is an excerpt from an article on presidential inaugurations in the January-February 2013 issue of the LCM. Written by Julie Miller of the Manuscript Division, this story takes a look at the inauguration of George Washington.

George Washington is depicted delivering his inaugural address on April 30, 1789, in this painting by T.H. Matteson, 1849.

April 30, 1789

George Washington’s inauguration on April 30, 1789, was literally without precedent. The Constitution mandated only that the president take an oath of office, and it prescribed the language of the oath, but it said nothing about how an inauguration day should go. Washington told the House and Senate committees formed to plan the inauguration that he would accept “any time or place” and “any manner” they chose. Finally, the shape of the day was determined not only by the committees but also by Washington himself and by the citizens of the capital city, New York.

The committees’ plan was set in motion when they escorted Washington, his speech folded in the pocket of his suit of American-made cloth, to Federal Hall at Wall and Broad Streets. A crowd of citizens followed behind the president-elect’s carriage. At Federal Hall, Washington stepped out from the Senate chamber onto the balcony. There, overlooking a large crowd of citizens, he took his oath on a Bible acquired at the last minute from a nearby Masonic lodge. “Long live George Washington!” shouted Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, who had administered the oath, reinterpreting the cheer traditionally used to greet monarchs. The crowd shouted back their approval.

The next part of the ceremony, the delivery of Washington’s inaugural speech before Congress, took place inside. Washington’s speech established a precedent that has been used by every elected president since, although its self-effacing tone was the mark of the 18th-century gentleman. He felt unequal, Washington told his listeners, to “the magnitude and difficulty of the trust” to which he had been called. As he spoke he trembled with nerves and emotion. Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay recorded in his journal that “This great man was agitated and embarrassed more than ever he was by the leveled cannon or pointed musket.” The president continued— reminding his audience, which represented “many distinct communities” that had not always been in concord—that the “sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the Republican model of Government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

That evening the celebrations began. Like those that followed, the first presidential inaugural was celebrated with a ball, which was postponed for a week pending the arrival of Martha Washington from Virginia. But that night a ship in the harbor shot off 13 cannon, houses were bright with illuminations, and fireworks lit the sky. When it was all over the streets were so crowded with people that Washington had to abandon his carriage and walk home. The next day the Daily Advertiser congratulated its readers: “Every honest man must feel a singular felicity in contemplating this day. – Good government, the best of blessings, now commences under favourable auspices.”

MORE INFORMATION

Research the Library’s holdings of presidential papers

View a web presentation of presidential inaugurations

View an online exhibition of inaugural collection items

You can read more about the inaugurations of presidents Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln and Calvin Coolidge here by downloading the complete January-February 2013 issue of the LCM .

January 18, 2013

Oath of Office

(The following is a guest article written by my colleague Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library’s staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

President Barack Obama next week will again take the oath of office on the Bible, drawn from the Library of Congress collections, that President Abraham Lincoln used at his first inauguration more than 150 years ago.

Obama took the oath on the Lincoln Bible at his first inauguration, in 2009. On Monday, the small, burgundy volume will have a companion at the swearing-in ceremony staged on the West Front of the U.S. Capitol: A Bible that belonged to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Obama will place his hand on the stacked Bibles as he takes the oath of office administered by U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Roberts – symbolically linking the president who emancipated the slaves during the Civil War with the reverend who led the civil rights movement a century later.

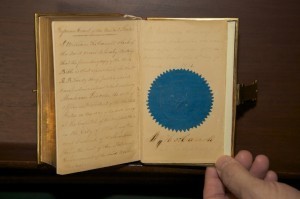

The 1861 Lincoln Inaugural Bible, opened to the page signed by the clerk of the Supreme Court, William Thomas Carroll, attesting that the book was used for Lincoln’s oath of office

“President Obama is honored to use these Bibles at the swearing-in ceremonies,” Steve Kerrigan, president and CEO of the Presidential Inaugural Committee, said on Jan. 10 in announcing the selections. “On the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, this historic moment is a reflection of the extraordinary progress we’ve made as a nation.”

The Lincoln Bible, housed in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, originally was purchased by William Thomas Carroll, clerk of the Supreme Court, for use during Lincoln’s swearing-in ceremony on March 4, 1861.

The Bible, a King James translation printed by Oxford University Press in 1853, is bound in burgundy velvet with a gilt metal rim around the outside edges.

The cover bears a metal shield inscribed with the words “Holy Bible.” The 1,280-page book is 5.9 inches long, 3.9 inches wide and 1.8 inches deep.

On inside pages, Carroll affixed a blue seal of the Supreme Court and inscribed a note certifying that the Bible was the volume upon which Lincoln took the oath. He also inscribed a personal note – a dedication to his wife: “to Mrs. Sally Carroll from her devoted husband Wm. Thos. Carroll.”

The book eventually found its way to the Lincoln family. In 1928, Mary Harlan Lincoln, the widow of Lincoln’s first son, Robert Todd, gave the Bible to the Library.

The Bible will be placed on display in the Civil War exhibition in the Jefferson Building from Jan. 23 to Feb. 18.

The Lincoln Bible’s companion at the inauguration on Monday will be a volume that, according to the King family, once served as the “traveling Bible” for the civil rights icon.

King usually traveled with a selection of books, often with this Bible. He used the book for inspiration and in preparing sermons and speeches – including during his time as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala.

“We know our father would be deeply moved to see President Obama take the oath of office using his Bible,” King’s children said in a statement. “His ‘traveling Bible’ inspired him as he fought for freedom, justice and equality, and we hope it can be a source of strength for the president as he begins his second term.

“We join Americans across the country in embracing this opportunity to celebrate how far we have come, honor the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. through service, and rededicate ourselves to the work ahead.”

Presidents traditionally have used Bibles during the swearing-in – there is no constitutional requirement – and often choose a volume with personal or historical significance.

At the first inauguration, George Washington used The Holy Bible from St. John’s Masonic Lodge No. 1 – opened at random and in haste to Genesis 49:13, according to the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies.

Presidents occasionally use that Bible for the swearing-in ceremony – Warren G. Harding, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush, for example, all took the oath on the same volume used by Washington.

Most have used a single book, but Obama won’t be the first to be sworn in using two Bibles.

Richard M. Nixon, for example, used two family Bibles. In 1949, Truman used a facsimile of a Gutenberg Bible as well as the Bible on which he was sworn in following the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt nearly four years earlier. Eisenhower used the Washington Bible as well as his own “West Point Bible.”

In 2009, Obama became the first president since Lincoln to be sworn in on that small, burgundy book.

On Monday, he’ll place his hand the King Bible and once more on the Lincoln Bible, connecting one of the nation’s great presidents with its greatest civil rights leader.

“Bibles used in inaugural ceremonies take on a certain resonance,” said Mark Dimunation, chief of Rare Book. “Certainly the use of the Lincoln Bible by President Obama has elevated this object to an iconic status – one that carries a great deal of emotional meaning to visitors when they view it. Employing it a second time and connecting it to such important anniversaries will only enhance this quality.”

You can see more images of the Lincoln Bible in this blog post from 2009, for President Obama’s first inauguration.

January 17, 2013

Library in the News: November and December Edition

With the whirlwind of the holiday season come to a close, let’s take a look back at some of the headlines the Library made in November and December.

One of our big announcements was the opening of the Library exhibition “The Civil War in America” on Nov. 12.

The Washington Post chose to highlight a select item – a little-known diary written by a wartime teenager – for its coverage of the exhibition. “A century and a half later, LeRoy Wiley Gresham’s smudges still mark the page, in a kind of communion with students of his remarkable record of the Civil War, the collapse of the Old South, and the last years of his privileged but afflicted life,” wrote Michael Ruane.

Where Guestbook did a great pictorial feature highlighting Civil War ambrotypes and a look at the Lincoln White House. And both CNN and The Examiner did website pictorials including such display items as a copy of President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address, a copy of Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, a set of children’s tinker toys and a lock of Ulysses S. Grant’s hair.

Martha M. Boltz of the Washington Times wrote about her tour of the exhibition, which had previously been thwarted because of Hurricane Sandy. “The exhibition on the Civil War, with its 200 unique items, is extraordinary and exhaustive … It was wonderful to tour with such a knowledgeable staff of archivists and curators. When one of them would start talking about a given display or artifact and paused for a moment, another would step in and add to it. The depth of knowledge of these dedicated professionals would be hard to find anywhere else.”

The Associated Press looked at the letters and diaries in the exhibition that “offer a new glimpse at the arguments that split the nation 150 years ago and some of the festering debates that survive today.”

Other outlets picking up the AP story included The Denver Post, The Huffington Post, ABC News, USA Today, Fox News, Yahoo! and several local papers in Mississippi, South Carolina, Missouri, Utah, Montana, Nebraska, Washington and Georgia.

In late November, the Library announced it would make available on its website a group of audio recordings featuring interviews from music icons. The audio recordings are part of the Joe Smith Collection of more than 225 recordings of noted artists and executives in the industry. NBC Nightly News with Brian Williams aired a brief segment. And outlets like the Los Angeles Times and examiner.com also ran headlines.

“The interviews are fascinating and worth a break from literary pursuits,” said Dave Rosenthal of the Baltimore Sun.

Speaking of the music industry, the Library announced in December that Carole King would be the recipient of the 2013 Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

Featuring the announcement were the New York Times, Washington Post, Rolling Stone, playbill.com, UPI, Reuters and the Associated Press. The AP story also ran in outlets including Billboard, the Washington Times, the Miami Herald, the Huffington Post, Salon.com and FoxNews.com. Broadcast affiliates far and wide for ABC, NBC, Fox and CBS also ran brief news segments.

In other entertainment news, the Library, also in December, added 25 new selections to its National Film Registry.

“‘Dirty Harry’ Callahan, Neo, Ralphie and his Red Ryder BB gun and the baseball-playing women of ‘A League of Their Own’ are taking a permanent field trip to the Library of Congress,” wrote Brian Truitt for USA Today, whose story includes brief segments of several of the films.

“One of the greatest productions on the long list of masterpieces produced by NFL Films has been selected for recognition in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress for its place in American culture,” said Josh Alper for the Pro Football Talk blog on NBC Sports. “They couldn’t have picked a better film than the one the Library of Congress calls the ‘Citizen Kane’ of sports movies to represent football’s enduring importance.”

Many other national and local outlets, including broadcast media, ran stories following the Library’s announcement.

On a final note, Library benefactor David Rubenstein gave the institution $1.5 million to fund three new literacy awards. Brett Zongker of the Associated Press reported the story, which was picked up by a variety of news media throughout the country.

January 16, 2013

Happy Birthday Flickr Commons!

Today marks five years since the launch of the Flickr Commons with two photo collections from the Library of Congress. Since then, more than 250,000 photographs with no known copyright restrictions have been contributed by 56 libraries, archives and museums worldwide, with new images added each week.

The Library’s blog, Picture This: Library of Congress Prints and Photos, celebrates this milestone with today’s post highlighting Flickr Commons contributors’ most viewed or interesting photos and other tidbits from the project.

Happy birthday Flickr Commons!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers