Library of Congress's Blog, page 174

June 10, 2013

Hollywood Mermaid

You know the old saying, “they don’t make them like they used to” – which is perhaps why I’ve always been a fan of classic movies. I’m more prone to get excited about one of them on the television than brand-new ones at the movie theater.

Esther Williams. 1945. Prints and Photographs Division.

The passing of a beloved actress, who I grew up watching, reminded me of this. Screen siren Esther Williams passed away last Thursday in Beverly Hills, Calif. She was 91.

I can see her scenes now: synchronized swimmers, fountains of water spraying everywhere, and her — center — coming up and out of the water, replete in gilded swimming suits, flowers in her hair. I was always fascinated by the fact that there were movies built around such swimming extravaganzas. And, yet, I was completely mesmerized and delighted.

Williams turned to Hollywood after failing to win the Olympic gold medal in 1940. She was only 17 when she won three gold medals and earned a place on the United States Olympic team. Unfortunately, the games were canceled with the onset of WWII.

She ended up becoming one of the biggest box-office stars of the 1940s and 50s. She appeared in more than 20 films, including “Bathing Beauty,” “Neptune’s Daughter,” “Million Dollar Mermaid” and “Ziegfeld Follies,” in which she played herself.

“I always felt that if I made a movie, it would be one movie,” Williams once said. “I didn’t see how they could make 26 swimming movies.”

“Ziegfeld Follies.” 1945. Prints and Photographs Division.

Over the course of her career, Williams ruptured her eardrums seven times – “I gave my eardrums to MGM” – broke her back taking a dive and nearly drowned, all because she did her own stunts.

Following her film career, she went on to lend her name to a retro line of swimwear and a swimming-pool company, among other things. In 1966, Williams was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

All in all, Williams believed she was “just a swimmer who got lucky.”

June 5, 2013

Inquiring Minds: An Interview with Marie Arana

(The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center.)

Photo by Clay Blackmore.

Author Marie Arana is a writer-at-large for the Washington Post and former editor-in-chief of Book World, as well member of the Library of Congress Scholars Council. Her latest book, a biography of Simon Bolívar, was extensively researched and written at the Library of Congress.

Q. Tell us about your new book, “Bolívar: An American Liberator,” and how you came to be interested him.

I have always been fascinated by Simón Bolívar. Two of my ancestors fought on opposite sides of the Battle of Ayacucho, which was the defining struggle—the Yorktown, the Waterloo, if you will—of the Latin American wars for independence. But quite apart from that personal connection, I was looking for a way to capture who Americans of Latin origin are, how we think, where we’ve been. The story that could deliver that history best, I became convinced, was the life of Bolívar. He was the quintessential Latin American hero, the founder, the visionary, and yet he died impoverished and despised. Along the way he liberated a vast, unruly territory that became six independent republics. His life touches on so much of South America and is representative of so many aspects—good and bad—of our character that I decided it was the perfect vehicle to explain South America to English-speaking readers.

Q. Where is scholarship on Bolivar currently and how does your book support or depart from it?

The scholarship depends on where you’re from. In Venezuela, Bolívar is idolized, and a biographer needs to pick her way through the hagiography. In Peru, he is despised and she’ll have to work her way in the opposite direction. Ecuador and Bolivia feel at once saved and injured by Bolívar: he had rough things to say about Ecuadorians, and he thought Bolivians were so disorderly that they needed a president for life. Colombia, on the other hand, has a very divided opinion: Colombia made heroes of his rivals, yet managed to exalt him, too. My greatest challenge—and, perhaps, accomplishment—is to have parsed through the partisanship carefully, relied on Bolívar’s words more than anything else, studied the world around him and made it past the tendentiousness.

Q. You spent a lot of time at the Library of Congress researching and writing this book. What items did you find in the Library’s collections that were most illuminating?

I spent almost a year at the Kluge Center. The great discovery for me was that everything I needed—documents that would have had to be hunted down separately and with some difficulty in South America—were in the Library’s remarkably rich and deep collection. Of course, I’m from South America, so I was well acquainted with Bolívar’s stomping grounds and had done early research in South America’s libraries, but I quickly found that much of what exists scattered in various places was sitting tidily in the stacks of the Library of Congress. Staring long enough at Caracas court documents from the late 1700s (Bolívar had a criminal record from the tender age of 12) to a street grid of his neighborhood, to a graphic of every kilometer Bolívar had ever traveled, I felt I was seeing and understanding aspects of his life that I hadn’t read anywhere else.

Q. You’ve spoken widely on the book since its release in April, on CSPAN and at book signings. What’s been the general reaction? Has any of the reaction been surprising in any way?

I’ve been fortunate in that the reaction has been overwhelmingly positive. I’ve also been pleased that there has been so much praise for the book’s liveliness and accuracy, the two aspects I cared about most in the writing. I wanted to bring the man alive, but I also wanted to say some important things about how history has shaped South America and made us different from Americans of the North. What surprised me, I think, was that one or two critics took me to task for making as much as I did of the Inquisition and Spain’s harsh colonial system. Some recent scholarship has questioned the “Black Legend” of Spain’s colonial rule. But to deny the Inquisition, the evidence of Spain’s violent conquest and spoliation of Latin America, not to mention the crippling Laws of the Indies . . . well, that struck me as intellectually unsound. But, as I say, Bolívar’s story can be polarizing. What amazed me is that, 200 years after the fact, the gloves are still on for some Spanish intellectuals.

Q. You’re very involved with the Library of Congress and the Kluge Center, from serving on the Scholars Council to helping with the National Book Festival and International Summit for the Book. What caused you to get involved with the Library, and how do you see the Library’s contributions to scholarship and promotion of “the book?”

The Library is one of the great wonders of the world. I don’t say that lightly. As a book professional all of my life—an editor at two New York publishing houses; editor-in-chief of a major, national literary review; and, finally, author of my own books—I have stood in awe of the institution. More than that, I am in awe of the wisdom of the American founders, librarians and public servants who built the Library with such a broad, generous sense of what knowledge should mean to a democracy. The Library of Congress may have started as an establishment meant to serve the United States of America, but it quickly became a library to serve the world. I was honored to be invited by the Kluge Center to do my research under its auspices, and I have always seen it as a sacred mission to take my love of reading and books to a wider world. So, you see, it was only natural that I would want to become involved in the vital work that goes on at this Library. I’m very glad to be a small part of it.

“Bolívar: An American Liberator” is published by Simon & Schuster and is currently available in bookstores. Marie Arana discusses the book on Thursday, June 6, at 4 p.m. at the Library of Congress John W. Kluge Center, co-sponsored by the Library’s Hispanic Division.

June 3, 2013

A Special Recording to Celebrate Casey’s 125th

This is a post by Gayle Osterberg, the Library’s Director of Communications.

Herblock political cartoon referencing “Casey at the Bat”

There is joy in Mudville today, as we mark the 125th anniversary since “Casey at the Bat” was first published on June 3, 1888, in the San Francisco Examiner.

The poem, dubbed the “single most famous baseball poem ever written” by the Baseball Almanac, has inspired everything from political cartoons to entire operas.

Written by Ernest L. Thayer – pen name Phin – “Casey at the Bat” has also been recorded multiple times, including this classic 1909 recording by De Wolf Hopper in the Library’s National Jukebox.

In honor of this momentous occasion we invited our friend Dave Jageler, a radio announcer for Major League Baseball’s Washington Nationals, to record his own interpretation of this poetry classic. We love the result, which will be archived in the Library’s Recorded Sound section, to be enjoyed by generations of baseball fans to come.

May 29, 2013

Civil War Chic

When looking at some clothing trends of today, with their bright colors and patterns, daring necklines, couture price tags and sometimes general wackiness, it’s hard to imagine how far fashion has actually come.

Silk Ikat dress, ca. 1855. Ikat is a dyeing technique that makes the pattern in fabric. Photo by Mary D. Doering.

According to Mary D. Doering, an heirloom-clothing collector, despite the trauma imposed by the Civil War, the mid-19th century witnessed the development of ready-to-wear garments and the growth of urban department stores, both of which were essential contributions to the modern American fashion industry.

Doering delivered a lecture at the Library of Congress last month discussing fashions from the period of 1855 to 1870, with an emphasis on the Northern states. She also addressed the evolution of the garments’ styles, the accompanying foundations, related technology and media marketing.

Technological innovations had much to do with the culture of clothing during the era. The growth of the mill and the Industrial Revolution were essential in providing fabric and democratizing fashion by making it affordable.

“In the 19th century, pricing was based on the volume of textiles used, which allowed for more modest pricing,” said Doering.

Roller printing technology ensured that the replication of patterns could be printed on cotton cloth – a technique that was also less labor intensive than hard woodblock printing. In addition, the invention of the power loom and sewing machine made for rapid production of clothing items.

Much like today, fashion magazines aided in marketing the clothing. Godey’s Lady’s Book, founded in 1830, was a leader in the industry. Almost every issue included an illustration and pattern – like ones from Butterick – with measurements for a garment to be sewn at home.

“Godey’s had a national distribution,” said Doering. “The railroad and improvement of transportation methods evened the playing field in reaching a broad spectrum of the population.”

Godey’s success inspired other publications, including Peterson’s Magazine and Graham’s Magazine, of which Edgar Allan Poe was editor from 1841-1842.

Thanks to the fashion media, designers were coming into their own, as well as retailers.

Godey’s fashions for February 1865. Prints and Photographs Division.

“Fashion advertisements tended to be generic, but you would also see specific retailers referenced,” said Doering.

One of the principal department stores of the time was A.T. Stewart Department Store in New York. According to Doering, A.T. Stewart’s was not only a place to shop but also a travel destination.

“It occupied a whole city block,” said Doering. “Women would make a pilgrimage to visit.”

Mail order sales were also becoming increasingly popular, and Marshall Field’s was an innovative leader.

So, what did fashion of the Civil War era actually look like? Doering brought several examples of dresses, separates and other accessories. One could not talk about this period without highlighting the hoop skirt, which personified the fashion of the time.

“It was innovative because women could reduce the number of petticoats,” she explained.

Style-wise, pagoda-like sleeves, military-inspired details and white-shirt separates were very popular.

“By the time of the Civil War, women’s undergarments also became more decorative and feminine,” said Doering.

One of the garments Doering showcased was a corset that featured an 18-inch circumference, expandable to 20 inches.

“That’s about the circumference of a roll of Bounty paper towels,” she said.

May 21, 2013

Notes? Check. Words? Check. Pipes? Check!

It’s no great surprise that Carole King has become the first woman to win the prestigious Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song– what a talent. She was co-writing hits that got huge airplay when she was still a teen in bobby sox: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” “Take Good Care of My Baby,” “One Fine Day,” “Up On The Roof.”

Carole King, winner of the Gershwin Prize

But one of the most satisfying things about her storied career is how she wrote song after song and hit after hit for everyone’s voice, it seemed, but her own – and when she finally put her own singing behind her own words, the result was “Tapestry,” an album that blew the doors off the music industry.

That breakout 1971 album remains one of the best-selling record albums of all time. It became the first solo album by a female artist to reach the Recording Industry Association of America’s “Diamond” status, meaning it sold more than 10 million copies. (Actually, more than 25 million copies.) Packed with hits – “You’ve Got A Friend,” “It’s Too Late,” “I Feel The Earth Move,” and her own rendition of “Will You Love Me Tomorrow”—“Tapestry” was named to the Library of Congress National Recording Registry in 2003 as worthy of preservation for coming generations.

Tonight her voice was heard once again, as Carole King and a cast of stars celebrated her career and her prize in the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium, closing with rousing collective renditions of “You’ve Got A Friend” and “I Feel The Earth Move.” Tomorrow night, she’ll sing again at the White House, and President Barack Obama will present her with the Gershwin Prize medal.

Is there a moral to this amazing story? Sure. Something like: Share your gifts, but don’t forget to share them with yourself.

Congratulations to Carole King.

May 20, 2013

A Cabinet of Gold

(The following is a story written by Martha Kennedy for the May-June 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM.)

The Library’s new exhibition “The Gibson Girl’s America: Drawings by Charles Dana Gibson” features works by a great American master of pen-and-ink drawing selected from the Library’s Cabinet of American Illustration.

In his 1910 illustration “Know All Men by These Presents,” Coles Phillips’ depiction of the “Fade-away Girl” is reminiscent of the “Gibson Girl.” Prints and

Photographs Division.

The story of how drawings by Gibson (1867-1944) and other illustrators became part of the cabinet presents a fascinating case history of building a collection. A special initiative launched in the 1930s enabled the Library to acquire many masterworks from the Golden Age of Illustration (1880-1930), a pre-radio and pre-television era when illustrated books, magazines, and newspapers provided essential sources of entertainment, enlightenment, and self-improvement for the American public.

The cabinet came into being largely through the dedicated efforts of William F. Patten, who persuaded Leicester Holland, then the chief of the Library’s Division of Fine Arts (now the Prints and Photographs Division), to start a collection of original illustration art for the nation. Holland provided modest support to Patten as he contacted illustrators or their heirs to request original drawings. As the art editor of Harper’s magazine in the 1880s-1890s, Patten was passionate about illustration and knew many leading illustrators and pursued his mission with urgency, as many of them were elderly and had not always saved much of their work.

Most leading Golden Age illustrators acquired excellent drawing skills through fine-art training and applied their best efforts to completing book, magazine and advertising assignments—often on tight deadlines. Although peak demand for illustration drawings had passed by the 1930s, Holland and Patten both comprehended the artistic and cultural significance of the art form. In the Librarian’s 1932 annual report, Holland asserted that illustration “was probably not only the most highly developed art in this country but had reached a higher development here than anywhere else in the world.”

When Patten contacted Gibson, the artist replied in a letter that he was honored by the invitation, supported the endeavor, and pledged gifts of his work, promising “only those that can make the grade.”

His response was typical of many illustrators and their heirs. By 1935, Gibson had generously donated more than 75 exemplary drawings, most featuring his signature creation, the “Gibson Girl”—a vibrant new feminine ideal. These included some works from two of his best known series, “The Education of Mr. Pipp” and “The Weaker Sex.”

The Cabinet of American Illustration grew rapidly and today numbers 4,000 drawings and prints by more than 250 artists. From 1933-1939, the Library mounted exhibitions of newly acquired works, thereby affirming enthusiastic support for building the collection and recognizing the high esteem in which illustration art was held. The cabinet’s holdings of outstanding works by leading illustrators embody the diverse array of styles, genres, techniques and subject matter characteristic of the art form during its Golden Age. Today, the Library continues to acquire selected examples of original illustration art.

The Cabinet of American Illustration is an excellent resource not only for enjoying individual works of art on paper but also for studying how artists influenced one another. Images of Gibson’s idealized young women inspired imitators as well as rivals, and examples of other illustrators’ icons of feminine beauty abound in the cabinet. “Know All Men by These Presents” by Coles Phillips (1880-1927) beautifully represents his stunning creation, the “Fade-away Girl.” Wladyslaw Benda (1873-1948) fashioned the “Benda Girl,” an exotic, almond-eyed beauty that graced the covers of Hearst’s International Magazine and other magazines. Nell Brinkley (1886-1944) portrayed her “Brinkley Girl” in such lovely forms as “Golden Eyes,” her dynamic World War I heroine.

Strong representation of several prominent women illustrators also distinguishes the cabinet’s excellent coverage of Golden Age illustration. Among them, Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954), Jessie Wilcox Smith (1863-1935) and Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932) all became known and well-respected in a field dominated by men. This was no small feat when illustrators were often public figures, and some, like Gibson, even achieved celebrity status.

Along with Gibson, Stephens gained standing when she won a commission in 1897 from the Ladies’ Home Journal for six cover drawings that alternated with his cover designs. Among more than 90 drawings and prints by her in the cabinet are award-winning works also considered her finest book illustrations—for George Eliot’s “Middlemarch” (1899), and Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Marble Faun” (1900). The cabinet also holds Daniel Carter Beard’s drawings for another classic, Mark Twain’s “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” (1889).

In addition to illustrations for literary classics, the cabinet holds many drawings created for popular fiction and children’s readers. Rosina Emmett Sherwood (1854-1948) drew an amusing example of the latter, “Miss Cloud and Miss Sunbeam” (1888) for “Harper’s Third Reader.”

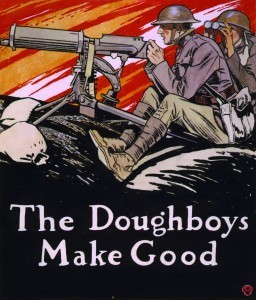

The Library mounted exhibitions of works by both Stephens and Edward Penfield (1866-1925) in 1936. Penfield, who was influenced by French poster design, took a leading role as a poster artist and key player in the transformation of magazine covers into poster-like designs. His drawing in the cabinet, “The Doughboys Make Good” (1918) stands out vividly among his many masterful works as a model of innovative design and use of color in WWI cover art.

Edward Pennfeld’s 1918 cover design for Collier’s magazine highlights the bravery and skill of the “doughboys,” the American infantrymen of World War I.

Prints and Photographs Division.

The cabinet holds hundreds of other war-related drawings, including dramatic scenes of military action by William Glackens (1870-1938) and pointed cartoon commentaries by W. A. Rogers (1854- 1931). Gibson, too, created powerful cartoons sharply critical of Germany during WWI and the current exhibition includes examples of his engagement with such leading political issues later in his career.

By virtue of their artistry alone, Gibson’s drawings represent a crowning glory within the Cabinet of American Illustration. Known primarily for drawings of archetypal beauties for magazines, he was surprisingly versatile and prolific, like many of his peers, producing book illustrations, advertising posters and political cartoons. His work offers a window into the visual riches to be found in the Cabinet of American Illustration, a collection of original art that reflects and visually documents the multi-faceted experiences and aspirations of American society during an era whose final years signal transition toward modernism in

American art forms.

This article is featured in the May-June 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

May 17, 2013

Library in the News: April Edition

April was a month of honors for the Library of Congress – from feting a sports legend to honoring achievement in fiction to an all-out Grammy nod.

On April 26, the Library celebrated the achievements of veteran sportscaster Bob Wolff, whose collection the institution also acquired. Outlets including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Baseball Nation, WTOP and the Washington Examiner, among others, all ran stories leading up to the event and afterward.

“The stories behind his stories remain vivid,” wrote Tyler Kepner for the New York Times. “The interviews are compelling historical documents, and Wolff preserved many of the early ones on 16-inch lacquer discs – slices of sports’ oral history on pizza-size records.”

“The best way to describe sportscaster Bob Wolff is a treasure,” said Thom Loverro for the Examiner. “The best way to describe Wolff’s life is that it has been a treasured one.”

On April 25, celebrated novelist Don DeLillo was named the first recipient of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction, which will be presented to him at the 13th annual National Book Festival in September. National Public Radio, The Washington Post, , CBS News, the Associated Press and the Miami Herald all ran stories.

“His most famous books have explored the prevalence of conspiracies, violence and political terror in a world of mass media saturation,” wrote Ron Charles for The Washington Post. “He’s still pounding away on his Olympia typewriter, transcribing his startling vision of modern America.”

And, adding another honor to its name, the Library of Congress was honored by the music industry with a special Grammy Award for its work to preserve historic audio recordings. The Associated Press wrote an article that was also featured in outlets across the country. In addition, broadcast coverage included affiliates of CBS, ABC and NBC.

“The Grammys on the Hill Awards are meant to connect the music industry with the world of policy and politics in Washington,” wrote the AP’s Brett Zongker. “Songwriter Kara DioGuardi said the library’s preservation work is critical.”

Speaking of preservation efforts, online magazine The Connectivist featured a great story on the Library’s digitization efforts.

“The library works with old books so brittle their pages go to powder if turned, and their spines snap when opened too far. Slides and negatives can crack beneath insensitive hands,” wrote Emma Bryce. “There are papers and maps so old and impossible to handle that without digitization, they’d never meet the public’s gaze. Digitizing, then, becomes a way to ‘protect’ the materials by preserving them for generations to come.”

May 7, 2013

Rising Up Out of the Myths

It’s the year 1933. There’s a 13-year-old kid in the front row at the movie palace. He’s watching “King Kong,” completely transfixed.

And there, in the flickering light of the screen, in the roar of the soundtrack, a famous career is born – as a youngster named Ray, already obsessed with dinosaurs, tells himself “Wow. I want to learn how to make creatures like that.”

Ray Harryhausen — whose “stop-motion” animation using models that appeared to move after being painstakingly filmed, frame-by-frame, as their articulated bodies were adjusted just a bit this way and then just a bit more – died today at the age of 92.

He is famously remembered for the scene in which skeletons engage in swordfights with live-action heroes (“Jason and the Argonauts,” 1963). His film “The 7th Voyage of Sinbad,” (1958) featuring a cyclops, a dragon, and another sword-wielding skeleton, was named by the Librarian of Congress to the 2008 National Film Registry of movies deemed worthy of preservation due to their cultural, historic or aesthetic value.

Harryhausen, a friend of science-fiction giant Ray Bradbury, became synonymous with the best of fantasy and sci-fi moviemaking from the 1940s (when Harryhausen assisted on the film “Mighty Joe Young”) through the early 1980s, when Harry Hamlin met Harryhausen in “Clash of the Titans.” (Hamlin played Perseus, and no less an actor than Sir Laurence Olivier played Zeus in this Greek mythfest.)

Then computer-assisted special effects overtook the field. But many special-effects artists and directors whose work features these latest effects pay homage to Ray Harryhausen.

Here’s a link to a museum in England that contains much of Harryhausen’s collection.

What’s your favorite Ray Harryhausen movie?

In Retrospect: April Blogging Edition

The Library of Congress blogosphere published lots of great content in April. Following is just a highlight.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

An “Appalachian Spring” Collaboration

Students from the Baltimore School for the Arts talk about working with the Music Division collections.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

The Great Sheet Cake Mystery

Jennifer Harbster researches the origins of the Texas Sheet Cake.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

In God We Trust

Margaret Wood uncovers the history of this national motto.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Older Personal Computers Aging Like Vintage Wine (if They Dodged the Landfill)

Older computers can have secondary value.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

What’s the Difference Between the National Archives and the Library of Congress?

Stephanie Greenhut and Stephen Wesson discuss the key differences between the two institutions.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Fresh Eyes on a Classic: Photographers Share Pictures of the Main Reading Room on Flickr

Selected favorites from visitors during the President’s Day Main Reading Room Open House are featured.

Copyright Matters: Digitization and Public Access

Cumulative Motion Pictures and Dramas

Seven more volumes of the Catalog of Copyright Entries from 1891 to 1978 have been digitized.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

“But Why Write a Poem?”: Remembering Danial Hoffman

Former Consultant in Poetry Hoffman passed away March 30.

May 4, 2013

The Bird is the Word

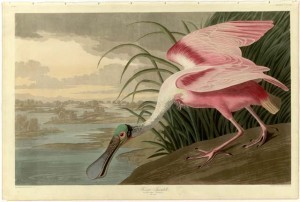

Roseate Spoonbill from “The Birds of America.” 1836. Rare Book & Special Collections Division.

“Bird” has been the word around my house lately. And, today, we celebrate Bird Day – a holiday established in 1894 by Charles Almanzo Babcock, a school superintendent in Oil City, Penn. Babcock hoped the initiative would promote conservation and awareness to the public, especially school children.

Recently, a friend of mine started talking about “The Big Year” bird-watching competition and her desire to participate. And, I’ve been enlisted to help. The informal competition takes bird watching to a whole new level, with birders vying to spot or hear the largest number of bird species within a single calendar year and within a specific geographical area. Sandy Komito holds the current record with 748 species seen in North America in a calendar year. Neither of us are really bird watchers, so things will certainly be interesting on this adventure. Fortunately, we can look to some Library of Congress resources in preparation.

Perhaps we could use as our starting point the works of John James Audubon (1785-1851), known for his famous drawings and paintings of North American birds. The first edition of his “Birds of America” book, also known as the “elephant folio,” is the largest book in the Library, at 39.37 inches high.

Cardinals with red tanager from “American Ornithology.” 1808. The Filson Historical Society.

Searching the Library’s Prints and Photographs online catalog for the title displays several lithographs from the book. In addition, a of paintings from his penultimate “Birds of America” can be found in the Library of Congress presentation “The First American West: The Ohio River Valley, 1750-1820” along with a three-volume ornithological biography with descriptions of the birds found in the book.

Another resource is the bird illustrations by painter Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1874-1927), whose work is featured in (1899) as part of the Library presentation “The Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920.”

Scottish ornithologist Alexander Wilson (176-1813) made a comprehensive study of the birds of North America by studying the specimens skillfully mounted and displayed by artist Charles Wilson Peale and his sons in the Philadelphia Peale Museum. The museum became the repository for a wide array of natural history specimens from commercial and government-sponsored expeditions. Wilson’s masterwork, would eventually grow to nine volumes and was the first comprehensive survey published on the birds of North America.

Just as important as knowing what the birds look like is knowing when and where to actually find them. The Library’s Science, Technology and Business Division has put together a reference guide on using space-based technology like remote sensing to track bird migration.

Annual convention of the American Ornithologists’ Union held at the American Museum of Natural History, November 1935. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library is also home to the papers of ornithologists Hans Hermann Carl Ludwig von Berlepsch (1850-1915), who was one of the first zoologists to apply Darwinian principles of systematic classification to the study of birds; Charles Bendire (1836-1897), honorary curator of the Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution; W.L. McAtee (1883-1962), an expert on the food habits of birds; and T.S. Palmer (1877-1954), former secretary of the American Ornithologist Union.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers