Library of Congress's Blog, page 173

July 16, 2013

Inquiring Minds: An Interview with Author Jason Emerson

Jason Emerson is a journalist and an independent historian who has been researching and writing about the Lincoln family for nearly 20 years. He is a former National Park Service park ranger at the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Ill. His previous books include “The Madness of Mary Lincoln,” “Lincoln the Inventor” and “The Dark Days of Abraham Lincoln’s Widow, as Revealed by Her Own Letters.” He discusses his newest book on Robert T. Lincoln, Abraham and Mary’s oldest and last-surviving son, today at the Library. Read more about it here.

Jason Emerson is a journalist and an independent historian who has been researching and writing about the Lincoln family for nearly 20 years. He is a former National Park Service park ranger at the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield, Ill. His previous books include “The Madness of Mary Lincoln,” “Lincoln the Inventor” and “The Dark Days of Abraham Lincoln’s Widow, as Revealed by Her Own Letters.” He discusses his newest book on Robert T. Lincoln, Abraham and Mary’s oldest and last-surviving son, today at the Library. Read more about it here.

Q. Tell us about your new book, “Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln” and how you came to be interested in him.

A. My book is a cradle-to-grave biography of Robert Lincoln — only the second ever done and the first since 1969 — that examines him not only as his father’s son but also as his own man. Robert was an amazing person with numerous accomplishments, and myriads faults and mistakes, during his 82 years of life. He is generally considered the most successful presidential son in American history (financially and as a private citizen) not including Adams and Bush who became presidents like their fathers.

Professionally and politically, Robert was a Chicago attorney (eventually one of the biggest in the city), supervisor of the town of South Chicago, secretary of war under Presidents Garfield and Arthur, minister to Great Britain, president or board member to numerous telephone, railroad, electricity and other companies, and, finally, president and chairman of the board for the Pullman Car Company. He was also the keeper and protector of his father’s papers and legacy for more than 60 years. He was a self-made man who died a multi-millionaire.

I became fascinated by Robert many years ago when I learned that the Republican Party tried five times to get him to run for president, but he had no interest in the White House and so demurred every time. I wrote an article about it, and as I did research for that article, I kept finding more and more unknown, unpublished information about Robert that really needed to be told. I prefer writing about aspects of history that have not been written about ad nauseum, and Robert, I discovered, was not only practically ignored in the annals of Lincoln scholarship, but the few things actually written about him were typically mistaken, misinterpreted or downright mendacious. So after numerous articles about aspects of his life I decided I should just write his life.

Q. Little has been published about Robert Lincoln. What has made him such a previously unknown historical figure?

A. Robert was an extremely private and reticent person, which was one reason. During his life, he almost always refused to insert himself into his father’s (or his mother’s) legacy, often by stating he really knew nothing interesting enough to tell. It turns out Robert had volumes of fascinating stories to tell (which he did in his personal correspondence to family and close friends), but his self-effacing refusals were his way of politely excusing himself from the spotlight.

Also, because Robert was at Harvard College during the Civil War, historians have assumed (incorrectly) that he was never in Washington and therefore knew nothing about his father’s administration — and therefore knew nothing of interest to their work. I actually discovered that Robert was not only in Washington constantly, but he was in fact his father’s confidant during some of the most trying times of the war.

I have never understood why Robert has been a persona non grata in Lincoln studies. As the oldest son, he was alive and aware of his parents private lives in Springfield moreso than anyone else; as a college student he was not only aware but could comprehend what his father suffered through the war; and as the only surviving son for the next 60-plus years, Robert knew everyone and everything relating to his father that writers and historians continuously searched for. During my research I found a literal treasure-trove of documents not only about Robert but about Abraham, Mary, Willie and Tad, the Civil War, the Lincoln papers, and on and on that no historian had ever used merely because they felt Robert too inconsequential to look into.

Q. Much of your research was done at the Library of Congress. What collections and/or items did you find most illuminating? What were the “previously undiscovered” materials you drew upon?

A. If you totaled up all my research time at the Library of Congress for this book I probably spent years there. I used dozens of collections in the Manuscript Division, looked through probably hundreds of old newspapers, consulted the legal law library, used the library’s general book collection and of course the prints and photographs division.

Every day I found something unknown or unpublished in Lincoln history. I found amazing items in the papers of every president after Abraham Lincoln during Robert’s life — they all wanted to be his friend, his mentor, his ally, to have that link to the Great Emancipator. And whenever they contributed to Lincoln’s legacy or memory, first they consulted Robert, so his hands are all over his father’s legacy. For example, Robert was intricately involved in the creation of The Lincoln Memorial for 20 years, and of course Robert donated his father’s papers to the Library of Congress.

The best thing I ever found was in Robert’s personal papers in the Library, which was only two folders at the time. I found a 15-page handwritten letter by Secretary of War Lincoln detailing day by day, even minute by minute, everything that happened from the moment President Garfield was shot by Charles Guiteau for the next seven days in the White House. Robert was only 40 feet away from Garfield during the shooting, and during the first week thereafter, Robert and Secretary of State James G. Blaine really ran the government. It was an amazing letter that I discovered had never been quoted, used or even referenced by any scholar. Ever. That was a great day.

Q. What is the story behind how you found Robert Lincoln’s papers? And how did you help the Library acquire them?

A. That is a long story that I tell in full in the last chapter of my book “The Madness of Mary Lincoln.” But, succinctly, I was doing research at Robert’s Vermont house, Hildene, where I found two letters that made reference to Mary Todd Lincoln’s “lost insanity letters,” or the letters she wrote from inside the insane asylum in 1875 that have been missing for over 80 years. Those two letters led me on a quest that ended five months later when I found the children of Robert Lincoln’s private attorney. They had in their attic (unknown to them) for 40 years a steamer trunk filled with Lincoln family documents, among them Mary’s missing letters. Most of the rest of the letters related to Robert, his wife and children and his grandchildren, but there was also some about his father.

The owners of the trunk did not know what to do with it, or if it was even valuable or should simply be destroyed. I told them the papers were invaluable and should certainly be kept intact. They decided to donate them to a safe historical repository and had many offers and ideas. When they asked my opinion I told them the three most appropriate places they should consider: the Library of Congress, the Lincoln presidential Library in Springfield, and Hildene, Robert’s Vermont Home. The family wanted a place that would be the most accessible to the public and that would appreciate the trunk, and I gave them the best advice I could. In the end they chose the Library.

Q. You’ve been researching and writing about the Lincoln family for nearly 20 years. What’s your interest/fascination with them?

A. They are just a fascinating family. But also, as I mentioned previously, I prefer ignored, untouched, unknown history and both Robert and Mary Todd Lincoln have lives that have been really ignored, maligned and misunderstood. So it is not only interesting to me to research and write about them, but the research almost always yields amazing discoveries. And since so few writers do anything about Robert and Mary, I have found my niche. Finally, the more I research, the more unknown and unpublished information I keep finding that forces me to continue on researching and writing about them, because I can’t just find this great information and then do nothing with it!

Q. Why do you think it’s valuable for the Library to preserve such historical collections, and what do you think the public should know about the importance of the Library’s mission to collect and preserve our historical and cultural heritage?

A. As Abraham Lincoln (and many others I’m sure) previously said, we can’t know where we are going if we don’t know where we’ve been. The study of history guides us, teaches us and, hopefully, its understanding prevents us from continually making the same mistakes as a society. Preserving historical collections is simply invaluable. It’s such a weighty idea and so important to me I don’t know how else to describe it.

Without knowing the history of our country, our communities, our extraordinary individuals humanity would be at a loss, a dog chasing its tail continually repeating itself because it would never learn how to evolve and strive for greatness and change.

The mission of the Library to preserve our historical and cultural heritage is one of the keystones of our collective identity. Its importance is evident in the number of people that visit and utilize the library every day, in the number of new books and materials donated and acquired every day, in the sheer ubiquity of the Library’s importance to understanding all academic disciplines.

When the Library was burned during the war of 1812, one of the first things Thomas Jefferson did was to give the country his own personal library as a foundation to rebuild the national library. Anything that important and essential to Thomas Jefferson is something to which we should all pay attention.

July 12, 2013

InRetrospect: June Blogging Edition

While school may be out for summer, Library of Congress blogs continue to educate and inform readers on interesting and valuable subjects. Following are a few selections from the month of June.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Gelukkige verjaardag! Eugène Ysaÿe at 155

Remembering the great Belgian violinist

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

“Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” — the ZIP Code is 50

A history of ZIP Codes

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

How Robin Hood Defied King John and Brought Magna Carta to Sherwood Forest

A retelling of the classic tale

The Signal: Digital Preservation

10 Resources for Community Digital Archives

Insightful resources for developing a community collection

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Our Second Anniversary

Celebrating two years in the Library blogosphere

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Whistler’s Butterfly

An artist’s monogram signature

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

Stay Gold: Robert Frost and First Poems

A coming-of-age poem

July 9, 2013

Inquiring Minds: Historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam

(The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center.)

Historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam is now concluding his tenure as the Kluge Chair in Countries and Cultures of the South at The John W. Kluge Center. His research looks at the first person narratives of early modern India and the new questions facing Indian historians. He lectures on the topic at the Library of Congress on Thursday, July 11. Read more about it here.

Historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam is now concluding his tenure as the Kluge Chair in Countries and Cultures of the South at The John W. Kluge Center. His research looks at the first person narratives of early modern India and the new questions facing Indian historians. He lectures on the topic at the Library of Congress on Thursday, July 11. Read more about it here.

Q: Tell us about your current research.

A: This is ongoing research with Muzaffar Alam from the University of Chicago. We’re concerned with first person narratives of India written in a variety of different forms between 1500 and 1800, during the Mughal Empire. This is what we call the early modern period. There’s been a lot of interest in these types of narratives in Europe, the Middle East and China. But in India, for whatever reason, no one has paid too much attention. To the extent that attention has been paid, it’s been mostly focused on memoirs written by the emperors. To get the emperor’s point of view is one thing; it’s quite another to get the view of others in the social structure.

Q: Can you give us a few examples of the kinds of first person texts you’re looking at?

A: One text that is relatively well-known is a text written by a merchant in the 17th century, written in a language similar to today’s Hindi. Interestingly, it is written in verse. It reflects on the author’s life as a merchant and an intellectual. Of the more obscure texts that I’ll be mentioning in my lecture, one is a text written by a man named Bhimsen Saksena who was a secretary, or a scribe, involved in the Mughal campaigns in Southern India. This is a funny case because the text has never actually been published—we are working from the manuscript. The last author is Anand Ram, a very prolific author from the 18th century. He was in the court in Delhi. These are interesting texts because he’s living in a moment with political turmoil. He also enjoys the good life and talks a lot about food. We don’t have a very good history of food in South Asia, so it’s interesting to see the names of dishes and recipes which are essentially the same as now.

Q: Do we have these materials at the Library of Congress?

A: At the Library we have editions and translations. For example, the Library has the whole set of works by the first of these authors. Print editions are rarely available digitally. Many of these things are still in copyright.

Q: What are the ramifications for this research? What gaps does it fill?

A: Actually, historians don’t reason anymore in terms of gaps. That kind of assumes that history is a building that you go at brick by brick. Instead, the attention of historians in India has shifted. The main questions used to be about taxation, peasants and merchants—sometimes with the big question behind us of why we didn’t have an Industrial Revolution in India. We’ve now moved onto other questions. By looking at these autobiographies, we’re opening social and cultural history and finding a different angle of vision.

Q: Does South Asian history particularly resonate with you given your heritage?

A: Yes, but I don’t think that one should insist too much on this. It’s my job to teach everybody, and everyone can learn from each other’s histories. So I like to separate those questions out. No one should be ashamed to study one’s own culture. But sometimes we have a tendency to insist too much that things must associate with our own identity and heritage.

Q: How do you reflect on your time at the Kluge Center and as the Kluge Chair in Countries and Cultures of the South?

A: The Kluge Chair has significance because I know two of the previous holders, who are both senior colleagues and friends: Romila Thapar and Christopher Bayly. The main thing, though, is the huge set of collections available under one roof here at the Library of Congress. That makes a big difference. Quite nice, too, has been the interaction with the post-doctoral fellows at the Kluge Center. Also it has been a pleasure to get to know the staff in the various reading rooms. It turns out that someone in the Russia Section is the son of an old friend. So that’s been a real treat.

July 8, 2013

Library in the News: June Edition

Leading the news headlines in June was the announcement that Natasha Trethewey would return for a second term as U.S. poet laureate.

“Natasha Trethewey likened her most recent poetry reading at the Library of Congress to a church revival in the South, complete with tents and believers making enough noise to make nonbelievers come in and listen,” wrote Deborah Barfield Barry for Gannett News Service. “Trethewey marked the end of her first year as the nation’s poet laureate last month with a personal and emotional lecture about why poetry matters to people in their everyday lives. She isn’t done spreading the word.”

“Her signature project will involve filming a regular feature on the PBS NewsHour Poetry Series, in which she and NewsHour senior correspondent Jeffrey Brown travel the country for a series of on-location specials that examine societal issues through a poetic lens,” announced Washington Post reporter Monica Hesse on Trethewey’s second-term plans.

Trethewey spoke with Entertainment Weekly’s Adam Carlson about her appointment and project with PBS.

“Because I’m a younger laureate, it seemed important to me to do something, not to just accept the honor of the position but actually make it useful,” she said in the interview. “Deciding to put a personal slant on it seemed to be what I might be good at. NewsHour is very interested in poetry, but they’re also interested in not just that something’s cute to add on at the end of their programming, but something that actually is integrated into the news.”

Also running an announcement was the New York Times, Christian Science Monitor and the Associated Press.

Also in the news were stories on the Library’s week-long Teacher Institutes promoting the use of primary sources in the classroom. Community newspapers far and wide ran stories of local teachers who participated in the program. Teachers came from Washington, Illinois, Minnesota, Virginia, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Missouri and California to name a few.

For a final piece of interesting news, the National Journal ran several historic photographs from the Library’s collections on baseball, specifically the Congressional baseball game.

July 3, 2013

A Presidential Fourth

George Washington. Published by Currier & Ives, [between 1856 and 1907]. Prints and Photographs Division.

Recently my dad gave me an interesting little tidbit concerning further research he has done on our family tree that is particularly auspicious for the occasion of today’s Fourth of July celebrations. (As you may recall from this previous blog post, my father has found a new hobby in ancestry research.) As it turns out, his research has led him to believe I’m related to George Washington – specifically as a cousin on Dad’s side of the family. Incidentally, he also found out that a relation on my mother’s side, Charles Lee, served as Washington’s attorney general during his second term, but that’s a story for another time perhaps.This revelation started me wondering how Washington commemorated our country’s independence, considering he was a distinguished general and commander in chief of the colonial armies during the American Revolution and later the nation’s first president.

Although July 4 didn’t become a legal holiday until 1870, the tradition of Independence Day celebrations goes back to the 18th century, following the adoption of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Concerts, bonfires, parades and the firing of cannons and muskets often accompanied the first public readings of the important document. In his general orders, dated July 3, 1778, Washington gives these instructions:

“Tomorrow, the Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence will be celebrated by the firing of thirteen pieces of cannon and a feu de joie of the whole line; the Army will be formed on the Brunswick side of the Rariton at five o’clock in the afternoon on the ground pointed out by the Quarter Master General. The soldiers are to adorn their hats with green-boughs and to make the best appearance possible. The disposition will be given in the orders of tomorrow. Double allowance of rum will be served out.”

The following year, Washington wrote in his general orders that the day would be commemorated “by the firing of thirteen cannon from West Point at one o’clock p.m.” In the same missive, he granted a general pardon to all army prisoners under sentence of death.

A few diary entries make passing commentary on Washington’s celebration plans. On , while visiting Lancaster, Penn., during a presidential tour of the “southern” part of the country, Washington wrote, “This being the anniversary of American independence and being kindly requested to do it, I agreed to halt here this day and partake of the entertainment which was preparing for the celebration of it.”

It was here he made his one and only speech about the Fourth of July.

After his presidency, Washington retired to his Mount Vernon estate where he received guests and was seen about town. According to his diary entry of July 4, 1798, the morning was clear but breezy with temperatures around 78 degrees. He participated in an Independence Day event near Alexandria.

From an annotation to his diary entry: Gen. Washington was escorted into town by a detachment from the troop of Dragoons. He was dressed in full uniform and appeared in good health and spirits. At 10 o’clock . . . uniform companies paraded . . . the different corps were reviewed in King Street by General Washington and Col. Little, who expressed the highest satisfaction at their appearance and manoeuvering; after which they proceeded to the Episcopal Church, where a suitable discourse was delivered by the Rev. Dr. Davis.

The Library of Congress is home to the papers of George Washington.

June 28, 2013

Story Time Returns at the Young Readers Center

The author Pat Mora has a word for it: Bookjoy.

Kids get into Story Time at the Young Readers Center

If you’re a lover of books, you won’t have to look that up in a dictionary – you’ll just know, instinctively, what it is. But where were you when you first experienced the joy of books?

Odds are it was on your mom’s, dad’s or a grandparent’s lap, having a book read to you – or at your local library, having a lively adult bring a storybook to life for you.

The Library of Congress Young Readers Center, in Room G29 of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building at 10 First Street S.E. in Washington, D.C., is again starting up its popular Story Time program for infants and toddlers.

The stories will be read on Fridays from 10:30 am. to 11:15 a.m. There is no charge, but space is limited, so tickets are distributed on a first-come, first-served basis beginning half an hour before the scheduled start time.

The Friday program is for little ones who come with parents, grandparents, caregivers, babysitters and even older siblings. The sessions are based on themes (this month’s theme is animals) and future story times may be tied to holidays, literary forms such as poetry, or events at the Library such as “Take Your Child to Work Day.”

The storytelling gets the children involved – in addition to the telling of the story, kids participate in rhymes, songs, and movement, including finger play and larger motor activities.

For more information on Story Time, see the Library’s website at www.read.gov. And don’t forget that the Young Readers Center is for youthful readers from very young children to teens, and offers onsite access to a variety of excellent books.

June 26, 2013

Library in the News: May Edition

Let’s take a look back at some of the headlines from last month. The Library had several celebrity visitors in May, including lots of musicians and even Swedish royalty. Making the biggest headlines was singer-songwriter Carole King accepting the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. She was feted at both the Library and the White House May 21-22.

King told the Associated Pressthat it’s a tremendous honor to be recognized at such an historic place in history that she never would have expected. “It is yet another of the many important messages to young women that women matter, women make a difference,” she said. “That popular music is recognized by the Library of Congress as being worthy of a place in history is especially significant to me.”

Bloomberg News noted that a flag in King’s honor would be flown over the Capitol, according to Mississippi Congressman Gregg Harper.

UPI ran several pictures from the White House concert.

USA Today, Washington Post, Washington Examiner, NPR, salon.com and national and affiliate stations of CBS, NBC and ABC ran stories.

A writer in his own right, composer John Adams – who Anne Midgette of the Washington Post calls “the face of new music” – was in residency at the Library at the end of May, presenting and conducting a series of concerts.

“I particularly love the people at the music department at the Library of Congress,” Adams told Washington Times reporter Matthew Dicker. “The archives there are lovingly cared for. It’s just a joy to be at the Library of Congress.”

In other celebrity sightings, media picked up news of a visit from the King Carl XVI Gustaf and Queen Silvia of Sweden, who took a tour of the Library while visiting Washington, D.C.

The Library’s Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation continues to regularly make the news. In May, PBS Newshour ran a piece on the conservation efforts done by the facility.

“Today, the treasure being protected is cultural, an effort born of a growing concern that audio and visual recordings were disappearing, in some cases misplaced, ignored or forgotten, in others due to film and tape literally disintegration,” said reporter Jeffrey Brown. “At the Conservation Center, technicians work on those that have managed to survive, however damaged, in an effort to ring them back to a form that can be copied, preserved and shown once more.”

June 19, 2013

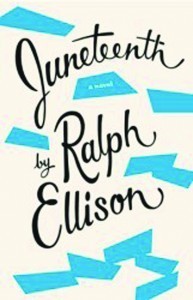

Trending: Juneteenth

More than 40 states celebrate the day that Texans learned of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

More than 40 states celebrate the day that Texans learned of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The news came late—two-and-a-half years late—and in the form of an official pronouncement. Known as “General Order No. 3,” the edict was delivered by U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger from the balcony of a mansion in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865.

But to the African-American population of the Texas territory, it might have come direct from heaven out of the mouth of an archangel: President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing them from slavery.

The widespread joy in Galveston and other Texas towns nearby as the news spread—and commemorative celebrations in other places around the U.S., held over many years and today in virtually all states—became known as “Juneteenth,” a day observed by African Americans and their fellow citizens in memory of that date of glad tidings (the name combines “June” and “nineteenth”). Today more than 40 states officially recognize Juneteenth as a state observance, and there is a movement to have it declared a national day of observance, similar to Flag Day and Mother’s Day.

The Library of Congress holds Lincoln’s handwritten first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, and displayed it early this year in its “The Civil War in America” exhibition in Washington, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

In addition to being the name of the time-honored celebration, “Juneteenth” is also the title of African American writer Ralph Ellison’s novel, published posthumously. The Library of Congress holds the papers of Ralph Ellison—best-known for his classic novel “Invisible Man”—in its Manuscript Division and Ellison’s library in its Rare Book and Special Collection Division.

MORE INFORMATION

Finding Aid to Ralph Ellison Papers

View webcasts (here and here) of Library programs about Ralph Ellison

This article, written by Jennifer Gavin, is featured in the May-June 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

June 14, 2013

InRetrospect: May Blogging Edition

The Library of Congress blogosphere was blooming with great posts. Here are a selection.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

To Richard Wagner on His 200th Birthday: A Textilian Tale Retold

Letters reveal insight into the composer’s private life.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

The Aeronauts

Jennifer Harbster writes about Civil War aeronautics.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Certain baby names are banned every year in New Zealand.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Fifty Digital Preservation Activities You Can Do

Susan Manus presents a list of ways to get involved in digital preservation.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

June in History with the Library of Congress

Danna Bell-Russel looks ahead at some important dates in June.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

A Window on Heritage and Home

A shop window honors Jewish heritage in its display.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

Mona Van Duyn and the Women of the Catbird Seat

Caitlin Rizzo pays homage to the first female Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry at the Library.

June 12, 2013

Experts Corner: The Art of Collecting

(The following is an interview from the May-June 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM.)

Martha Kennedy, curator of “The Gibson Girl’s America: Drawings By Charles Dana Gibson,” discusses illustration art with Richard Kelly, curator of his collection of American illustration.

Martha Kennedy: You have developed a remarkable collection of illustration art along with a library that supports research in the field. Could you tell us a little about how and when you began building your collection?

Richard Kelly: The Kelly Collection of American Illustration got its start in 1987 when I bought a Mead Schaeffer painting from a friend of mine. Later that year, I bought a painting by Howard Pyle from an auction and the seeds were sown. Soon after that my focus changed—my taste “matured” entirely toward the older works and from then on my collecting centered entirely on Golden Age Illustration (1880-1930).

MK: What special subject interests, themes, and principles have guided you in the process of developing your collection?

RK: I was fortunate in that very early on I set some guidelines that gave the collection a more manageable focus. The collection is entirely American, and from the Golden Age time period. We don’t collect what is known as “pulp” or “pinup art” and have only a few children’s book illustrations or western-themed paintings. Within those parameters, we have tried to collect all of the important illustrators in both breadth and depth. We consistently focus on quality, trying to get the very best that each artist was capable of throughout his or her career.

MK: Could you share some thoughts on the impact of illustrators’ images of the “ideal woman” on the market economy at the turn-of-the-19th century?

RK: The improved printing technology of the 1890s began a boom in publishing periodicals in America, and images of the “ideal woman” quickly played a major role in decorating their pages. These idealized women graced the pages of American magazines and books and dominated our advertisements well into the 20th century.

MK: Have you found it useful to consult and view parts of the Library’s Cabinet of American Illustration as a resource over the years as you developed your collection? If so, how has it been useful?

RK: While I was an intern at the Library in the late 1990s, I was introduced to the Cabinet of American Illustration. I was astounded at the number of pieces in the collection and quickly realized it could help me in my own collecting. The quality of a piece can only be determined by a careful comparison within a broad range of an artist’s work. By comparing works that came up at auction with the vast holdings of those artists at the Library, I was able to more easily determine if they deserved a place in the Kelly Collection.

MK: What would you consider the strengths of the Cabinet of American Illustration?

RK: The major strength of the Cabinet of American Illustration is its enormous scope and size. With over 4,000 works, it is a major repository for this type of art. Additionally, almost all of the works were executed between 1890 and 1940, so virtually every illustrator working on paper during that period is represented here, most with multiple examples. As a result, the cabinet represents the major archive for important illustrators such as Gibson, Elizabeth Shippen Green, Joseph Pennell and Edward Penfield, as well as its extensive holdings of many other artists’ work.

MK: What are some of the ways you think American illustration art has contributed to America’s artistic legacy?

RK: In the late 19th century, illustrators in this country made the transition directly from easel painting to illustration. As a result, they devised a style that was more robust than that of their European counterparts, both powerful and distinctly American. Throughout the Golden Age of American Illustration, there were tens of thousands of quality works produced, all of which aesthetically conveyed the emotional impact of the stories and advertisements they illustrated. They provided countless Americans with an introduction to art available nowhere else in their everyday lives. Now those same illustrations give the visual detectives of today a clear window into the culture and values of this very exciting period in American history.

This article is featured in the May-June 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers