Library of Congress's Blog, page 175

May 3, 2013

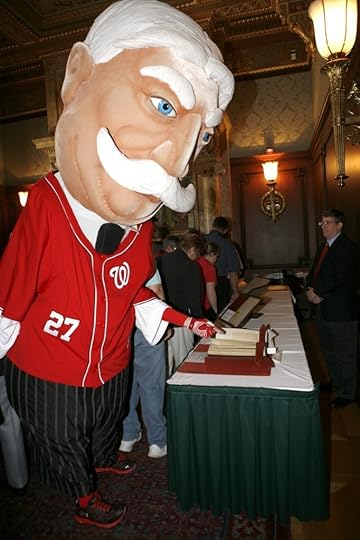

Pic of the Week: Taft in the House

Photo by Abby Lewis Brack.

Washington Nationals newest mascot, William Howard Taft, stopped by the Library of Congress last Friday during a special event celebrating the acquisition of the historic recording collection of Hall of Fame sports broadcaster Bob Wolff. A selection of Library treasures was put on display for guests, including Taft’s papers, which the National’s mascot is seen here perusing.

During the event, the 92-year-old Wolff, who was the pioneering television voice of the Washington Senators for 15 years, wowed the crowd with a review of his more than 74-year career as a sportscaster. He entertained with stories and personal anecdotes about the sports legends he interviewed over the years — among them, Babe Ruth, Jim Thorpe, Vince Lombardi, Ted Williams, Joe Louis, Yogi Berra, George Steinbrenner, Clark Griffith and Rocky Marciano.

April 29, 2013

Duke Ellington’s Film Debut

The Washingtonians, ca. 1925.

One of the great joys of working with the Library of Congress film and video collections is learning more about our holdings from the astonishing variety of researchers the Moving Image Reference Center attracts. While we’re justifiably proud of our in-house expertise, we rely on patrons, scholars and consultants to help us understand even more about our treasures.

A perfect example of this happy circumstance happened just recently when we were contacted by Ken Steiner, an historian specializing in the life and work of Duke Ellington, whose 114th birthday we celebrate today. I’ll let Ken set the stage:

Duke Ellington’s early days in New York are a Prohibition-era tale of torrid jazz, hot shows, Broadway stars and Treasury raids. Before he rose to fame at Harlem’s Cotton Club, Ellington spent three and a half years in a cellar dance club and cabaret near Times Square, which had opened as the Hollywood in September of 1923. Ellington assumed leadership of the house band, the Washingtonians, in February 1924, and they cut their first record late in the year. By 1925, the Hollywood had re-opened as Club Kentucky, and the Washingtonians had developed a small following for their “indigo modulations.”

I was doing some research on the Washingtonians when a one-sentence paragraph in the June 13, 1925, edition of the Philadelphia Tribune caught my attention:

“Johnn[y] Hudgins, the Kentucky club band and four girls from the club Alabam have been filmed in the Rue La Paix [sic] scene in a feature film called ‘Headlines’ being produced by the St. Regis Picture Corp.”

I immediately knew that “the Kentucky club band” had to be Duke Ellington’s Washingtonians, the only band to have played at the club to that point. The question then became: was there a copy of the film “Headlines” still in existence?

So, Ken immediately googled “Headlines 1925,” which led him to a website devoted to the film’s star, Alice Joyce, where he learned that “a copy of this film is located at the Library of Congress (35mm, not preserved).” He contacted Reference Specialist Zoran Sinobad, who in turn alerted me to this tantalizing possibility.

Our nitrate print of the silent film “Headlines” was indeed unpreserved. It was acquired from the Netherlands Film Archive (now called EYE Film Institute Netherlands) in 1992 and has Dutch intertitles. One of the first steps in film preservation after physically preparing the reels is setting the exposure levels for individual scenes, otherwise known as “timing” or “grading” a film. I asked timer Frank Wylie to keep an eye out for the Rue de la Paix sequence and, if possible, get some frame grabs that might help identify Ellington. He did—with his phone’s camera—but despite the poor resolution and the fact the band remains far in the scene’s background, I sent them to Ken with eagerness and trepidation. He quickly responded that he had shared the stills with several other Ellington experts and that they unanimously agreed the fellow with the distinctive “bean-shaped head” at the piano was definitely Duke Ellington. “Headlines” has since been fully preserved, although we still have some work to do in translating the intertitles.

So while we may wish that the Washingtonians had been favored with a closeup, we’re pleased to present Duke Ellington in his (so far as we know) first ever film appearance, thanks to the detective work of Ken Steiner. This clip is excerpted from the seven minute nightclub sequence.

[media player not shown]

April 22, 2013

Perspectives on the Environment

Nature. Environment. Earth. Each of these words points to a particular physical phenomena, but their meanings are different. And people’s perspectives of them are different.

From left, David H. Grinspoon, Jean-Francois Mouhot and Matthias Klestil discuss the environment during a Kluge Center panel discussion. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

On Feb. 28, the John W. Kluge Center brought together three of its scholars to discuss these perspectives and their moral implications in a panel titled “The Evolving Moral Landscape: Perspectives on the Environment, Literary, Historical and Interplanetary.” And, what better time then Earth Day today to take a look at perceptions of human’s relationship to our planet and its environs.

According to American astrobiologist David H. Grinspoon, the first Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology at the Kluge Center, humans are now changing the earth “as a kind of new type of geological force.” We are in what he calls the Anthropocene, a phrase that scientists and others are increasingly using to describe the current phase of earth history.

“The Anthropocene is focusing these questions of the relationship between humanity and nature in a new way,” said Grinspoon. “Should we be pragmatic? There’s ecopragmatism where you recognize we live on a planet that’s permanently altered by humanity, and rather than seek to return to or preserve pure wilderness, we recognize that’s an illusion and we proceed under the new knowledge that we live, in fact, in a human-dominated planet.

“Then there are these more purist movements within environmentalism that say that’s surrender. We should seek to protect wilderness and not give up and admit that we live in a human-dominated planet. So as we go forward into the future the Anthropocene serves as a sort of locus for some of these questions – is nature something that we can even think of meaningfully anymore as separate from humanity, or do we acknowledge that now having arisen from nature we are actually running this place?”

Environmental historian Jean-Francois Mouhot, a Marie Curie Fellow from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Paris), presented his take on climate change, using slavery as an example, and the underlying moral issues. Mouhot believes that at some point in the future, we may be held accountable for reparation to other countries and people for things that we do today, in terms of our impact on the environment. He used the Haitian Revolution as an example. The slaves revolted in the country that became Haiti and became dependent. Years later, France forced Haiti to essentially pay them for that loss of property in order to give them diplomatic recognition. According to Mouhot, that was normal at that time.

“Driving cars or taking planes or drying your clothes in the dryer … activities that we all do on a regular basis that we find normal and nobody really finds morally appalling or anything like that,” he said. “Now, if you think about the implications of the use of these machines that all rely on fossil fuels … in the light of the Anthropocene about the fact that we are now altering especially the climate of the earth but also that we are disrupting a lot of other things through our activities, this might in the future be regarded as activities that are not morally neutral.”

Bavarian Fellow Matthias Klestil from the University of Bayreuth in Germany, who is researching the development of environmental consciousness in African-American literature, discussed how the African American community is perceived in regards to its relationship with nature and the environment. Citing an August 2009 trip taken by President Barack Obama to Yellowstone, the media exchange that followed really triggered the perception of how deeply unfamiliar the image of not only Obama but of an African-American in general enjoying a frontier setting seemed to be, he said.

“You know, we might not find much if we think about African-American literature in terms of having an explicit activist or conservationist/preservationist ethics underlying,” Mouhout said. “So instead I’m implying the wider definition of environmental knowledge. I’m looking at the ways in which there are specific attachments or identifications with nature in African-American literature.”

Using slavery as a case in point, he talked about three aspects to this environmental consciousness.

“First, there is the aspect of vision. So I look at how, for example, the fugitive slave narrative has a different mode of visually relating and perceiving nature than, you know, mainstream transcendentalists have,” he said. “The second aspect would be that of labor. So what does it mean to actually work with environments under slavery but also more general terms? How does that shape the human’s relation to natural environments, having actually to do work but not just going there in their free time?”

The third aspect, he said, revolves around the abolitionist debate versus the pro-slavery debate of nature.

“Basically both sides are in a sense drawing on nature,” Klestil said. “One side is saying slavery is unnatural, and the other side is saying slavery is totally natural because that’s how they [slaves] were made, what they were made for.”

The John W. Kluge Center brings scholars and best thinkers to the nation’s capital to utilize the Library’s collections, to energize and inspire one another and to engage in dialogue with leaders in Washington and the public.

You can watch the panel discussion in full here.

Grinspoon summed up the discussion: “We have to learn to become a new kind of entity on this world that has the maturity and the awareness to handle being a global species with the power to change our planet and use that power in a way that is conducive to the kind of global society we want to have.”

April 17, 2013

InRetrospect: March Blogging Edition

While March may have “gone out like a lamb,” the Library’s blogosphere offered a wealth of great posts. Here’s just a sampling.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Lincoln and the Blair House Binder’s Volumes

Sharon McKinley talks about musical scores belonged to the Blair family, a prominent family during the Civil War.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

Getting to Know Sir Arthur C. Clarke

Jennifer Harbster posts about Arthur C. Clarke, chairman of the British Interplanetary Society.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Marmite: A Sticky Legal Situation

Former New Zealander Kelly Buchanan writes about the New Zealand-made condiment and some legal importation issues.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Death, Taxes, Digital Audits and PUPPIES!

How to get and keep your digital tax and financial files in order.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Stereotypes and Humor in Historic Films from the Library of Congress

A guide for students in exploring how humor in film changes over time.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Caught Our Eyes: A Giant Bat Roost?

The Prints and Photographs Division spotlights an early 20th century photo of a bat roost.

Copyright Matters: Digitization and Public Access

Copyright Digitization: Moving Right Along

Mike Burke reports on the digitization efforts of the Copyright Card Catalog.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

Radical Form: Lesley Dill’s Poem Dress of Circulation

Art intersects with poetry in Dill’s “Poem Dress.”

April 12, 2013

A Birthday Fit for a President

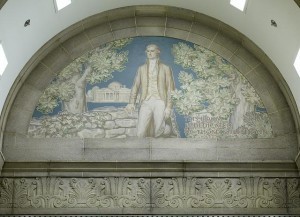

Mural of Thomas Jefferson with his residence, Monticello, in the background, by Ezra Winter. Library of Congress John Adams Building. Photo by Carol Highsmith.

Saturday is the 270th anniversary of Thomas Jefferson’s birth (April 13, 1743). And, the Library of Congress owes much to this esteemed third president. After the British invaded Washington in the War of 1812, they burned down the Capitol building, including the Library of Congress collection housed there. Jefferson, an avid book collector, sold his 6,487 volumes – the largest personal collection in the United States – to help restart the Library.

Jefferson was renown for being many things: author of the Declaration of Independence, father of the University of Virginia, founding father of the nation, respected scholar and prolific inventor.

The Library has original letters, cartographic materials, drawings, manuscripts and other items as part of its Thomas Jefferson Collection.

Several letters from the Library’s Manuscript Division reveal insight into Jefferson, who was a faithful public servant, powerful advocate of liberty, skilled writer and advocate of knowledge and learning.

In a letter to James Madison on Dec. 20, 1787, he defined what he did and did not like about the new federal Constitution, which was still being ratified by the states. He was “captivated by the compromise of the opposite claims of the great and little states.” However, Jefferson was disturbed by the lack of a bill of rights, which “is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth.” Despite his criticisms, he would support a ratified Constitution “in hopes that they [the states] will amend it whenever they shall find it works wrong.”

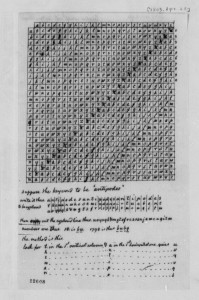

Cipher from Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis, April 20, 1803. Thomas Jefferson Papers.

January of that same year, Abigail Adams had corresponded with Jefferson, expressing her concern about the uprising led by Massachusetts farmer and Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shay over pain caused by the state’s postwar financial policies. Calling the protestors “ignorant, wrestles desperadoes,” Adams believed they were without cause for their grievances. Jefferson disagreed and responded with a little daring: “I like a little rebellion now and then. It is like a storm in the atmosphere.”

Jefferson’s correspondence wasn’t limited to letter writing alone. When he sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark off to explore the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, he hoped for periodic reports along the way. To keep it all a secret, he gave Lewis a cipher. “Suppose the keyword to be ‘Antipodes,’” Jefferson wrote in his explanation for how to use the key. On the back he revealed a real keyword: Artichokes.

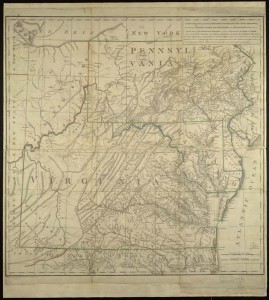

The Louisiana Purchase was a major coup in Jefferson’s presidency, and several maps from the Library’s Geography and Map Division highlight the Lewis and Clark expedition, whose primary purpose was to explore and map the newly acquired territory. A pre-expedition map is believed to be a chart that the intrepid explorers carried on their journey at least as far as the Mandan-Hidatsa Villages on the Missouri River, where Lewis annotated in brown ink additional information obtained from fur traders. In addition, the first printed map of the Lewis and Clark expedition (1810) was the first published map to display reasonably accurate geographic information of the trans-Mississippi West and was the landmark map that laid the foundation for the future mapping of the West.

Thomas Jefferson’s only published map. 1787. Geography and Map Division.

Considering Jefferson’s varied interests in geography and natural history, it should come as no surprise he dabbled in cartography himself. Jefferson’s only published map (1787) features the area between the Albermarle Sound and Lake Erie. It was prepared as a fold-out illustration for his sole book-length publication, “Notes on the State of Virginia.”

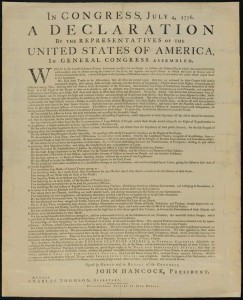

The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division holds perhaps the most significant piece of printing produced in the 18th-century colonies, the Dunlap Broadside. This was the first printing of the Declaration of Independence. It was produced in the evening following the final vote of the session.

The Dunlap Broadside. 1776. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

According to the National Archives, interest in reproductions of the Declaration increased as the nation grew. An unusual copy features the document printed on silk, known as the Ingraham 1823 Declaration, in honor of the three surviving signers: John Adams, Charles Carroll and Jefferson.

Another item is a rare satin broadside of Jefferson’s 1801 inaugural address. It is embellished with a portrait of Jefferson at the top, the only known broadside edition to be illustrated in such a way. Jefferson had actually requested the copy from printer Mathew Carey.

Other items include the first-known draft of Jefferson’s inaugural address, a survey – in his own hand – of his Elk Hill Plantation and a catalog of his library reflecting Jefferson’s preferred book organization into the categories of history, philosophy and fine art. (For many years, this manuscript was mistakenly labeled as a catalog of the University of Virginia library but was rediscovered in 1980 and properly identified.)

The Library is the home of Thomas Jefferson’s personal library and the largest collection of original Jefferson documents in the world.

April 11, 2013

In Bloom

Photo by Abby Brack Lewis

We’ve been on cherry blossom watch here at the Library, waiting for our 100-year-old cherry blossom trees to bloom. The grounds of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building are home to two of the original group of 3,020 Yoshino cherry trees given to Washington, D.C., in 1912, by the city of Tokyo as a symbol of friendship between Japan and the United States. And, these two beauties are among only nine remaining from that group.

Recently, one of the trees (pictured here), located at the corner of Independence Avenue and 2nd Street, was given a plaque to officially mark it as a commemorative tree.

Photo by Abby Brack Lewis

The Library commemorates the 100th anniversary of the gift of the cherry blossom trees with a webcast and an exhibition, “Sakura: Cherry Blossoms as Living Symbols of Friendship,” which explores the origin of the donation, the significance of cherry blossoms in Japanese culture and the friendship between Japan and the U.S. as symbolized through the trees.

April 9, 2013

First Batch of Authors for 2013 National Book Festival

Authors and poets Margaret Atwood, Marie Arana, Taylor Branch, Don DeLillo, Khaled Hosseini, Barbara Kingsolver, Brad Meltzer, Joyce Carol Oates, Katherine Paterson and U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey will be among more than 100 writers speaking at the 13th annual Library of Congress National Book Festival, on Saturday, Sept. 21 and Sunday, Sept. 22, 2013, between 9th and 14th streets on the National Mall. As always, the event is free and open to the public; it will run from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. on Saturday and from noon to 5:30 p.m. on Sunday, rain or shine.

Author John Green signs books for his fans at the 2012 Library of Congress National Book Festival. Photo by Richard Herbert

Other poets and authors slated to appear at the festival include Katherine Applegate, Rick Atkinson, Paolo Bacigalupi, Nicholson Baker, Bonnie Benwick, A. Scott Berg, Holly Black, Monica Brown, Steve Coll, Susan Cooper, Justin Cronin, Matt de la Peña, Katherine Erskine, Richard Paul Evans, Brian Floca, Eric Gansworth, Albert Goldbarth, Mark Helprin, Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Juan Felipe Herrera, Jennifer and Matthew Holm, and Kay Bailey Hutchison.

Also Pati Jinich, Adam Johnson, William P. Jones, Cynthia Kadohata, Jamaica Kincaid, Matthew J. Kirby, Jon Klassen, Kirby Lawson, Grace Lin, Mario Livio, Rafael López, Kenneth W. Mack, William Martin, Ayana Mathis, James McBride, D.J. MacHale, Heather McHugh, Lisa McMann, Terry McMillan, Elizabeth Moon, Christopher Myers, Phyllis Reynolds Naylor, Kadir Nelson, Patrick Ness, Katherine Paterson, Daniel Pink, Andrea and Brian Pinkney and Matthew Quick.

Not to mention Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome, Vaddey Ratner, Christel Schmidt, Jon and Casey Scieszka, Chad “Corntassel” Smith, Andrew Solomon, Sonya Sones, Walter Stahr, Manil Suri, James L. Swanson, Mark Teague, Evan Thomas, Steve Vogel, Dean Young, Charles Whelan, and Henry Wiencek. (Hmm. I guess we are mentioning them.)

What is more, internationally known illustrator Suzy Lee is creating the artwork for this year’s NBF poster.

This author list is just getting started! For details as they develop, go to www.loc.gov/bookfest/ .

April 8, 2013

Supporting Congress: Lawmakers and Their Library

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell for the March-April 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. Hartsell is editor of The Gazette, the Library’s staff newspaper.)

The Library’s mission is to support the Congress in fulfilling its constitutional duties and to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people.

By the time voters went to the polls in November, analysts in the Library’s Congressional Research Service (CRS) were hard at work researching the key public policy issues the newly elected representatives and senators likely would face when they convened on Capitol Hill nearly three months later.

The analysts in the Library’s Congressional Research Service identified roughly 160 such issues—from health care at home to political upheaval in the Middle East—and prepared research and reports that would be ready for use by the 113th Congress in the upcoming legislative session.

The research conducted by those analysts is but one service among many the Library provides to directly assist Congress in the performance of its legislative work. The Library offers members of Congress and their staffs a wide range of other support—legal research; guidance on important copyright issues; maps of global hot spots; expert, bicameral seminars on policy issues; information technology support; and, every two years, even the Bibles and bound copies of the Constitution newly elected members use in swearing-in ceremonies.

An act of Congress, signed by President John Adams, established the Library in 1800 to provide “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” Today’s Library still provides Congress with books—more than 30,000 volumes circulated to the House and Senate in the last fiscal year—but it serves in many other ways as well.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, CRS held an open house for members and congressional staff to help address constituents’ needs and concerns. Photo by Robert H. Nickel.

“The U.S. Congress created this amazingly library,” said Librarian of Congress James H. Billington. “For this, the Congress, past and present, deserves the most heartfelt thanks of all of us.”

Legislative Support

The research, analysis, seminars and programs produced by CRS provide Congress with a nonpartisan, confidential resource that helps members navigate the legislative process and address important, complex issues. Last year, CRS responded to about 700,000 congressional reference requests, delivered to Congress more than 1 million research products and offered a cadre of seminars and briefings.

CRS, for example, conducts a three-day orientation that provides newly elected members of the House with an overview of priority issues on the legislative agenda, legislative procedure and the budget process. The service also conducts programs that support Congress once the session gets underway – seminars, for example, that give members and their staffs the chance to meet with experts on a wide range of issues in an informal, confidential setting.

CRS has but one mission: Serve Congress in the performance of its work.

Similarly, service to Congress remains the Law Library’s first priority. Congress established the Law Library of Congress in 1832 with the mission of making its resources available to Congress and the Supreme Court—a mission that expanded over time to include other branches of government and the global legal community. Librarians and lawyers respond to congressional inquiries about U.S., foreign, comparative, and international legal and legislative research, drawing upon the world’s largest collection of law books and legal resources—more than 5 million items that span legal systems around the globe. Last year, the Law Library provided members of Congress with more than 300 in-depth reports, along with nonpartisan analysis and in-person consultations.

The Law Library’s legal reference librarians assist congressional and CRS staff any time either chamber of Congress is in session, no matter the hour. Law Library and CRS staff engage members of Congress through social media—RSS feeds, Facebook, Twitter, and blogs—on legal developments and course offerings.

Information Services

The Library brings together its unique combination of technical and congressional process expertise to provide Congress with a variety of information technology services.

The Law Library and CRS, working with the Library’s web services experts, maintain THOMAS, the Internet-accessible database that makes legislative information—bills, resolutions, treaties and the Congressional Record—available to Congress and the public. Congress.gov, a beta website operated jointly by the Library of Congress, the House, the Senate and the other legislative branch sources, provides the same information through mobile devices and eventually will replace THOMAS. The Law Library responds to all queries related to THOMAS and the Congress.gov beta site.

“Since the launch of the public legislative information system known as THOMAS in 1995, Congress has relied on the Library to make the work of Congress available to the public in a coherent, comprehensive way,” said Rep. Gregg Harper (R-Miss.) at the September 2012 launch of the Congress.gov beta site. “The Library staff has a strong working relationship with the House, Senate and the Government Printing Office, which will enable the Library to successfully develop the next generation legislative information website.”

Working with its legislative branch data partners, the Library launched a Congressional Record app on Jan. 16, 2012, and, on the following day, broadcast the first House committee hearing as part of a new streaming video project. Through the Congressional Cartography Program, the Geography and Map Division produces geospatial products for congressional offices and committees.

Register of Copyrights Maria Pallante (left) testifies before a congressional subcommittee on intellectual property rights and the Internet. Photo by Cecelia Rogers.

Copyright Issues

The Library of Congress also is home to the U.S. Copyright Office, where creators like Scott Turow and Taylor Swift and studios such as DreamWorks register books, songs or films for copyright to protect their rights as creators—more than 510,000 such claims were registered in fiscal 2012.

The register of copyrights—the director of the Copyright Office—also serves as the principal advisor to Congress on copyright issues. As such, the register works with the Senate and House Judiciary committees and with individual members to provide advice and technical expertise on copyright law and policy and to develop recommendations for potential legislative discussions in the future. The register also provides expert testimony before Congress and its committees.

Congress Comes to the Library

Curator Ed Redmond (left) shows items from the Geography and Map Division collections to (from left, at table) Reps. Gregg Harper (R-Miss.), Leonard Lance (R-N.J.) and Rush Holt (D-N.J.). Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

The Library’s three Capitol Hill buildings, all located within a block of the U.S. Capitol, frequently serve as meeting and event venues for members, including events in conjunction with the start of each new Congress. The Library provided space for more than 85 events for members in the last fiscal year: staff retreats, panel discussions, meetings with foreign legislators, luncheons, concerts and receptions.

The Congressional Relations Office, the primary point of contact between the Library and Congress, helps manage those congressional events and other services. Last year the office hosted nearly 500 visits by members and arranged tours for more than 84,000 constituents referred by 466 congressional offices.

The Congressional Relations Office also runs programs that provide service to constituents back home. For example, the office worked with more than 150 members of Congress last year to send surplus books to local libraries, schools and museums. Through another program, the office helped congressional staff teach educators in their home districts how to use the Library’s vast online resources in their own classrooms. Last year, the Library trained more than 27,000 teachers from 378 congressional districts to use primary sources in the classroom.

Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.), co-chair with Rep. Robert Aderholt (R-Ala.) of the Library’s Congressional Caucus, paid tribute in a November floor statement to the service the Library provides in helping Congress perform its constitutional duties. “Perhaps one of the best parts of serving in Congress is the access to our Library, the Library of Congress, the dedicated staff at CRS, and the magnificent Members Reading Room,” Blumenauer said. “The Library of Congress is truly a national treasure.”

A download of the March-April 2013 issue of the LCM is available here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

April 5, 2013

A Turn-of-the-Century “True Hollywood Story”

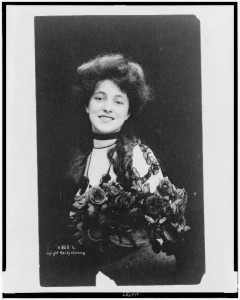

Evelyn Nesbit. Photo by Otto Sarony. 1901. Prints and Photographs Division.

In the 1890s, illustrator Charles Dana Gibson created the “Gibson Girl,” a vibrant, new feminine ideal—a young woman who pursued higher education, romance, marriage, physical well-being and individuality with unprecedented independence. Until World War I, the Gibson Girl set the standard for beauty, fashion and manners.

The Library’s new exhibition, “The Gibson Girl’s America,” which opened last week, pays homage to the artist, his iconic art and how women’s increasing presence in the public sphere contributed to the social fabric of turn-of-the-20th-century America. The exhibition is on view through Aug. 17 in the Graphic Arts Galleries on the ground level of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building

Charles Gibson used several models as his muses, including his own wife, Irene Langhorne, and Belgian-American actress Camille Clifford. However, it would be model Evelyn Nesbit that would bring scandal to the name. Gibson’s work, formerly titled “Women: The Eternal Question” (1905) – one of many he drew featuring Nesbit –remains one of his best-known pieces.

Nesbit was discovered at age 14 in Philadelphia, while working at Wanamaker’s department store. Her career as an artist’s model soon took off, and she moved to New York City in December 1900. She became an overnight sensation and the sole breadwinner for her family, first as a model for painters and sculptors, and then in the more lucrative field of posing for photographers, magazine illustrators and advertising. At 16, she took to the stage as a chorus girl in the Broadway musical “Florodora” and later as a featured player in “The Wild Rose.” The media quickly latched on to the young ingénue and the publicity hype soon followed.

Her beauty and talent did not escape the eyes of would-be suitors, including prominent architect Stanford White, who was 31 years her senior. White was very calculated in his pursuit of Nesbit. Ingratiating himself with her mother and friends, White cultivated the notion of himself as a father figure and benefactor. Through this trust, he was able to take advantage of the teenaged girl, seducing her one night while her mother was out of town. Nesbit and White carried on a relationship for nearly a year until she was sent off to a girls’ school in New Jersey at age 17.

“The Queen of Hearts,” possibly featuring Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, by Walter Dean Godlbeck. March 28, 1914. Prints and Photographs Division.

After her relationship with White ended, Nesbit certainly dated other men, but none would capture her until Henry Thaw. Thaw, heir to a $40 million fortune, pursued Nesbit relentlessly after seeing her on the Broadway stage. She resisted his advances and marriage proposals for nearly two years after breaking up with White – even confessing to Thaw what had transpired between her and her much older lover. The confession only enraged Thaw – who was believed to be a drug addict with myriad mental problems – and planted the seed for a fatal vendetta.

Nesbit did finally agree to marry Thaw, possibly because she realized she had few opportunities for a respectable marriage and financial security. On April 4, 1905, the two exchanged vows. A year later, Thaw and Nesbit ran into Stanford White at a rooftop performance of a new musical at Madison Square Garden. During the finale, Thaw approached White brandishing a pistol and shot him three times in the face. White died instantly. According to a New York Times account the following day, a witness heard Thaw saying “You ruined my wife” as he shot White.

Dubbed the “trial of the century,” the first trial in 1907 ended with a hung jury. During a second trial a year later, Thaw pleaded temporary insanity and was sent to the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in upstate New York. Thaw escaped to Canada, briefly, and was finally released from the asylum in 1915, after being judged sane.

The love triangle between White, Nesbit and Thaw and its violent end was fodder for the yellow journalism of the time, as the media sensationalized the story and its characters and dissected every detail. The Library’s Chronicling America site has several headlines from the New York Tribune.

The morning after the murder, headlines screamed of the tragedy.

“Looks Bad for Thaw,” “White Stories Untrue” said the July 5, 1906, issue.

As the first trial progressed, the paper was with it at every step.

“Thaw Jury Disagrees,” Discharged After Forty-Eight Hours of Wrangling,” “Nearly at Fisticuffs,” “Seven for Death; Five, Acquittal” announces the April 13, 1907, issue.

Harry K. Thaw leaving court. July 1915. Prints and Photographs Division.

Of course, other newspapers reported on the events surrounding the murder and trials

“Great Battle for Thaw’s Life” reads a headline from the Jan. 21, 1908, edition of the Hawaiian Star.

“Second Trial Opens Tomorrow; Prisoner Relies Upon Insanity Plea and His Girl Wife’s Graphic Life Story” said the Jan. 5, 1908 issue of The Washington Times.

“Thaw Found Not Guilty By Reason of Insanity – Sent to the Asylum” shouts a Seattle Star headline from Feb. 1, 1908.

These are just a sampling of the stories in Chronicling America. Just search for the key players – Harry K. Thaw, Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White – to pull many more.

Nesbit went on to find moderate success in vaudeville, as a burlesque dancer and as an art teacher in Los Angeles. She died at a nursing home in Santa Monica, Calif., in 1967, at the age of 82.

April 3, 2013

A League of Their Own

The Rockford Peaches. 1945. Library of Congress.

The other day at roller derby practice, the subject of women and baseball came up. Okay, to be fair, my teammates may have just been quoting lines from the movie “A League of Their Own,” which was recently inducted into the Library of Congress National Film Registry. But, nonetheless, with baseball season upon us, it’s no wonder the subject was on their minds.

The movie follows the real-life All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL), which celebrates its 70-year anniversary this year. The organization was founded the spring of 1943. Men all over the country were being drafted into the armed forces during World War II and with that came fear the Major Leagues might disappear. Chewing-gum mogul and Chicago Cubs owner Philip Wrigley proposed a professional women’s league to keep the sport in the public eye.

What started out as four teams – the Kenosha Comets, the Racine Bells, the Rockford Peaches and the South Bend Blue Sox – grew into some 10 teams and more than 600 women athletes. Initially softballs were used, but as the league grew, so did their adherence to regular baseball regulations like smaller balls, base stealing and full overhand pitching.

While these women may have been strong athletes, league officials strived to keep up the femininity of its players – from their short-skirted uniforms to their outward feminine appearance and deportment.

Dottie Schroeder (inspiration for Geena Davis’s character in “A League of Their Own”) was a slick-fielding shortstop and the only player to play all 12 years of the league, according to the AAGPBL. She started playing at age 15 with the Blue Sox but spent the majority of her career with the Fort Wayne Daisies. She also played on several All-Star teams.

Manager Jimmy Foxx and Dorothy Schroeder were models for the Tom Hanks and Geena Davis characters in “A League of Their Own.” 1952. Library of Congress.

In addition to playing 12 AAGPBL seasons, Schroeder holds all-time records for most games played (1,249) and most at-bats (4,129). She also produced the most RBIs in league history, 431, making her one of only five players to collect over 400 RBIs. Oh, and she was pretty and friendly to boot.

She listed “winning playoffs in 1954, South and Central American Tour in 1949, spring training in Havana, Cuba [1947] and just simply playing ball in each and every game” as her favorite memories in a questionnaire for the AGPBL Archives at the Northern Indiana Center for History. She passed away in 1996.

The League disbanded in 1954, following financial difficulties, declining attendance and the advent of televised Major League baseball games.

I think you could agree that these athletes were pioneering a new opportunity for women, which perhaps opened the door for future professional sports like women’s softball, basketball and hopefully, one day, roller derby.

The Library of Congress publication, “Baseball Americana,” features the story of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League and more, peppering each chapter of America’s favorite pastime with items from our baseball collection, one of the world’s largest.

Want to see more? We’ve gathered a variety of our online resources on baseball here.

Here are some more links where you may find information on your team or baseball in general:

Benjamin K. Edwards Baseball Card Collection

The Business of Baseball (Business & Economics Research Advisor)

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers