Library of Congress's Blog, page 172

August 5, 2013

Experts Corner: Civil Rights Collections

(The following is an interview from the July-August 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Adrienne Cannon, African American history and culture specialist for the Manuscript Division, discusses the scope of the Library’s civil rights collections.

When did the Library of Congress begin collecting material documenting the Civil Rights Movement?

Throughout its 213-year history, the Library has endeavored to document every facet of the African American experience. With the establishment of the U.S. Copyright Office in the Library of Congress in 1870, a large percentage of these materials have been collected as copyright deposits, while others have been acquired as gifts or through purchase and subscription. The Carter G. Woodson Papers, given between 1929 and 1938, provided the first manuscripts related to the fight for civil rights. The collection includes the papers of John T. Clark, a National Urban League official.

Several years ago the Library mounted an exhibition marking the centennial of the NAACP. How did the Library come to acquire this important collection?

The Library acquired the NAACP Records in 1964 with the help of Morris L. Ernst, a friend of Arthur Spingarn, the NAACP’s longtime counsel and president. Totaling approximately 5 million items, the NAACP Records are the largest single manuscript collection acquired by the Library— and the most heavily accessed.

The NAACP Records are the cornerstone of the Library’s civil rights collections. The Library’s comprehensive civil-rights collections also include the original records of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the National Urban League and the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights; and the microfilmed records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). These records are enhanced by the papers of such prominent activists as Roy Wilkins, Moorfield Storey, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Joseph Rauh, Mary Church Terrell, and Jackie Robinson. When Thurgood Marshall donated his papers to the Library in 1991, the documentation of his 60-year career, from civil rights lawyer to Supreme Court Justice, were finally brought together in one place.

Does the Library’s Manuscript Division continue to acquire material pertaining to the struggle for civil rights?

Yes. The Roger Wilkins Papers, a gift, arrived in January 2013. They chronicle his career as a civil rights lawyer, journalist and professor. In recent years, the division also received the papers of James Forman, Herbert Hill and Tom Kahn. Forman’s papers cover his leadership of SNCC, as well as his involvement in CORE, the NAACP and the Black Panther Party. Hill’s papers document his multi-faceted career, including his tenure as NAACP labor secretary. Kahn’s papers include his memoranda and notes on the 1963 March on Washington as first assistant to Bayard Rustin, the event’s chief organizer.

What other resources does the Library hold on the Civil Rights Movement?

In addition to the personal papers and organization records in the Manuscript Division, the Library’s other custodial divisions hold related resources in a wide variety of formats such as photographs, newspapers, radio and television broadcasts, film and sound recordings. The Library’s American Folklife Center preserves oral history interviews with those who experienced the movement first-hand. The Library is also collaborating with the Smithsonian Institution on the Civil Rights History Project, a congressional initiative to survey the nation’s existing Civil Rights-era oral history collections and to record additional interviews that will be housed in the American Folklife Center.

MORE INFORMATION:

August 2, 2013

Brush Stroke of Beauty

Hallway in the Library of Congress’s Thomas Jefferson Building. Photo by Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division

It is rather hard to believe that at one time some of the decorative murals that adorn every nook and cranny of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building weren’t even known to be there. In the decades after it opened in 1897, the building became increasingly overcrowded with growing staff and collections. By the 1970s, the Jefferson’s decorated spaces were obscured with partitions and dropped ceilings.

In the 1980s, the Architect of the Capitol (AOC) began major renovations to restore the splendor of the Jefferson Building for the American people. According to the AOC’s Barbara Wolanin, who was in charge of the murals restoration during the renovation, the original artists copyrighted their work and, that, coupled with historic photographs of the murals and construction records and letters in the Library’s Manuscript Division, helped AOC’s decorative painters and fine art conservators bring the murals back to life. You can read more about the project in this article from the December 1997 issue of the Library of Congress Bulletin.

“The Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress, remains, since its opening in 1897, the most elaborately embellished public building in the United States. It symbolizes and celebrates American achievements and values at the end of the 19th century in an elaborate iconographic program where the architecture, painting, sculpture and decorations work together almost seamlessly, a triumph of what we now call the “American Renaissance,” said C. Ford Peatross, founding director of the Center for Architecture, Design & Engineering in the Library’s Prints & Photographs Division. “The murals were executed by a number of artists, some of them the finest of the time, and they are a critical tool in conveying the Jefferson Building’s intended messages. Not only do the murals inform the increasing numbers of people who visit the Library of Congress, both in person and online, but their glowing colors and beautiful compositions provide a truly joyous experience. They are a public treasure that we must protect and preserve.”

Even today, AOC craftsmen continue their work in caring for the ornate walls of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building. Go behind the scenes in this video, produced by the AOC, with one of their decorative painters, Dean Kalomas, to see how they maintain the artistry of the building.

Make sure to check out the Architect of the Capitol YouTube channel to watch videos and learn more.

You can take a virtual tour of many of the Library’s spaces, including several of its most decorative in the Jefferson Building. For more information on the history of the Library of Congress and its buildings, see “Jefferson’s Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress” and “On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress.”

July 31, 2013

Death of a President

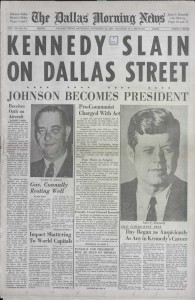

The Dallas Morning News announces a national tragedy. Serial and Government Publications Division

(The following is a story written by Library of Congress archivist Cheryl Fox for the July-August 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine. You can download the issue in its entirety here.)

As the American people struggled to come to grips with the death of president John F. Kennedy, the nation’s Library provided reference, refuge and remembrance.

Just after 10 p.m. on Nov. 22, 1963, White House Special Assistant Arthur M. Schlesinger called two Library of Congress officials at home to “relay an urgent personal request from Mrs. Kennedy.” Just nine hours after the president’s death, the calls on behalf of the newly widowed wife of John F. Kennedy were placed to Roy Basler, director of the Library’s Reference Department, and Manuscript Division Chief David C. Mearns. The request was for documentation of Abraham Lincoln’s lying in state.

According to William Manchester in “Death of a President,” First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy remembered an engraving of Lincoln lying in state that she had selected to illustrate the first public guide to the White House, published in 1962. The image showed Lincoln’s coffin, shrouded in black crepe, on a catafalque in the East Room.

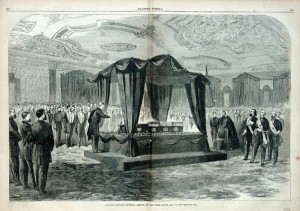

A 19th-century image from Harpers Weekly depicts Abraham Lincoln’s funeral. Serial and Government Publications Division

Mearns volunteered to go to the Library at once to get copies of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (later renamed Leslie’s Weekly) and Harper’s Weekly, in which the images could be found. He asked James I. Robertson, a noted Civil War scholar and executive director of the U.S. Civil War Centennial Commission, to join him, along with James Sutton, head of the Newspaper and Periodical Section of the Serial Division. Mearns and Basler later documented their activities, which are preserved as part of the Manuscript Division’s David C. Mearns Papers, 1918-1979. Mearns wrote:

Upon arrival, we went directly to the Manuscript Division, where I distributed flashlights. Mr. Sutton went off to collect Washington and New York newspapers. Dr. Robertson and I went to the Main Building to examine contemporary general periodicals. In Leslie’s Weekly we found excellent pictures of the scene in the White House’s East Room and in the rotunda of the Capitol. … We selected and marked those [newspapers] which contained the fullest and most precise accounts. I then called Dr. Schlesinger, and described to him the materials we had gathered together. He instructed us to deliver it to the Northwest Gate of the White House, which Dr. Robertson did. I reached home about half past one.

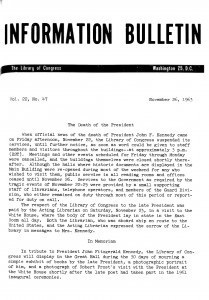

The Nov. 26, 1963, issue of the Library’s Information Bulletin notifies staff about procedures in the wake of the president’s assassination. Library of Congress Archives

Throughout the national period of mourning, from 3 p.m. on Friday, Nov. 22 until 9 a.m. on Tuesday, Nov. 26, a skeleton staff at the Library of Congress was at work. Basler, Mearns and many other staff members fulfilled numerous media requests, created reports on presidential succession and a bibliography on firearms-possession laws. They even offered the cold and weary mourners refuge in the Library’s Jefferson Building as they waited to file past the President’s coffin lying in state across the street in the U.S. Capitol. During the month that followed the state funeral, the Library presented an exhibition of books by the late president and other memorabilia.

July 29, 2013

Inquiring Minds: Studying Decolonization

(The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center.)

Each year the International Seminar on Decolonization, sponsored by the National History Center (NHC) and hosted by The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress, brings together young historians from the United States and abroad to Washington, D.C., to study and discuss the history of decolonization in the 20th century. The seminar takes place in July-August, and is generously supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. We sat down with Marian J. Barber, associate director of the NHC, to learn more.

Q. Tell us briefly about Decolonization: what does the term mean, and what period of history does it refer to?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “decolonization” as “the withdrawal from its colonies of a colonial power; the acquisition of political or economic independence by such colonies.” For the purposes of the International Seminar on Decolonization, it means the dissolution of empires, mainly in the period after the second world war and the emergence of new nations, particularly in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. The empires we focus on most are those of the European maritime powers such as Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Great Britain; but among the participants and the speakers whose lectures accompany the seminar have been scholars of Japanese, Chinese, Spanish and Italian imperial history and those who study the post-colonial Middle East.

While such conflicts are always a part of the seminar, a major emphasis has been what comes after, particularly the evolving relationships of newly independent states to their former colonial masters, as well as interactions among the new nations. Members of the seminar apply the techniques of sub-disciplines such as cultural, social, political, diplomatic, gender, economic and military history to help them understand and explain the ways that decolonization has helped reshape the world.

Q: Why the need for a Decolonization Seminar? How did it come about and what purpose does it serve?

The height of decolonization in the 1950s and 1960s was accompanied by the development of area studies programs, particularly those concentrating on Asia and Africa. Historians working in those fields often found themselves at odds with scholars of modern Europe and the U.S. The decolonization seminar is intended to bring the two groups together to create a new field that recognizes their differences and commonalities and builds upon both.

W. Roger Louis, member of the Library of Congress Scholars Council, founding director of the National History Center of the American Historical Association, and a leading scholar of the end of the British Empire, developed the idea of the seminar in 2005, in collaboration with the John W. Kluge Center. It has been funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation since 2006.

Q: What’s the connection to the Library of Congress? Why host the seminar at the Kluge Center each year?

The seminar was conceived early in the life of the NHC out of the longtime collaboration of Roger Louis and Prosser Gifford, then-director of the Library’s Office of Scholarly Programs, who had co-edited influential volumes on decolonization in Africa in 1982 and 1988. When Carolyn Brown became director of the Library’s Kluge Center in 2006, she continued the relationship, cemented when Roger Louis became a member of the Library’s Scholars Council in 2007.

The seminar continues to return to the Kluge Center each year because of the superior research facilities of the Library of Congress; the generosity and resourcefulness of the Library staff and the Library’s reference librarians; as well as the opportunity to be a part of one of the world’s great centers of intellectual endeavor. As historians, we particularly appreciate the opportunity to meet in the historic Jefferson Building!

Q: What is the study of decolonization helping us understand about our world today?

Decolonization helps us understand that the world we are encountering today is ever-changing, the product of the interactions of many cultures and societies and many different systems of economics and politics over many decades. By allowing us to see how today’s world of nations developed from a world of empires and colonies, it helps us envision a future unimaginable to the inhabitants of the colonial past.

Roger Louis lectures at the Library on July 30 at 4 p.m. in the Kluge Center, the final lecture of this year’s Decolonization Seminar. To learn more about the seminar, click here . To see a full list of this year’s seminar participants, click here .

July 26, 2013

A Rare Book By Another Obama

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell for the July-August 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine. The full issue is available for download here.)

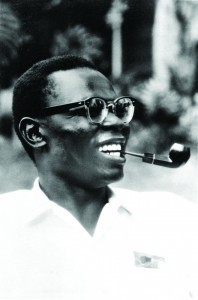

Barack Obama Sr. / Associated Press

The Library of Congress holds a rare book written decades ago in Kenya by the father of the 44th U.S. president.

The author’s name, listed on the title page, is familiar even if the language is not: “olosi gi Barack H. Obama.” The language is Luo, an African tribal dialect, and the Obama in question isn’t the 44th president of the United States, but his father.

The African and Middle Eastern Division of the Library of Congress holds an exceedingly rare copy—only four are believed to exist—of a book written decades ago in Kenya by the president’s father. “Otieno, the Wise Man,” or “Otieno Jarieko” in the original Luo, was published in Kenya in 1959 to promote literacy at a time when adult illiteracy was widespread.

The slim, 40-page volume also is the product of a collaboration that proved pivotal in the Obama story—the book’s editor helped Obama Sr. get to the United States, where he met and married a woman with whom he had the child who would become the first African American to be elected president.

“Books like ‘Otieno’ are part of the historical documentation of presidents and their families,” said Mary-Jane Deeb, chief of the African and Middle Eastern Division. “This book documents, in a tangible way, the father of the first African American president. It helps show what his values and interests were and helps illustrate what kind of man he was.”

“Otieno, the Wise Man” was a three-volume series produced by the Kenya Adult Literacy Program and published by the East African Literature Bureau to promote literacy as well as health, good farming practices and citizenship.

The Library holds copies of the first two volumes. The authorship of Vol. 1 is unclear: An illustrator is credited but no author is listed. Printed on the inside cover of Vol. 2, “Wise Ways of Farming,” however, is this note: “Written by Barack H. Obama for the Education Department of Kenya under the direction of Elizabeth Mooney, literary specialist.”

In his 2012 biography of the president, “Barack Obama: The Story,” author David Maraniss writes that Obama Sr. was performing clerical duties at the literacy program offices when the managers decided to publish primers in five tribal languages. Mooney chose Obama to write the Luo version.

“He was interested in bringing modern techniques to his homeland, and he realized he could make a bit of money through writing,” Maraniss wrote. “So for a time he willingly put himself into the mind of his wise fictional protagonist, Otieno.”

Obama’s tenure at the literacy program office ultimately was most important not for the book but for the connection he made with his editor, Mooney. “Betty” Mooney was an American who spent her life promoting adult literacy in India, Africa and the United States. In Nairobi, she headed a British government project that helped adults read in the local tribal languages.

In addition to the writing job, Mooney also offered to help Obama continue his education in the United States. According to Maraniss, entrance exams, served as a reference and provided financial support.

And crucially—though by chance—she helped Obama find the school he would attend. Leafing through the Saturday Evening Post magazine, she saw an article about a “colorful campus of the islands”—a school with a beautiful setting and a multiracial student body. She passed the article to Obama, who liked what he saw and chose to attend the University of Hawaii. There, he met Ann Dunham. They married and had the son who later became an American president.

The Library of Congress acquired its copy of “Otieno, the Wise Man” in March 1967—41 years before the author’s son was elected president and the historical significance of the book could be fully understood. It is believed that the acquisition was made possible by the Library’s Field Office in Nairobi, which was established the previous year.

Image from the Library’s copy of “Otieno, the Wise Man,” by Barack Obama Sr. / African and Middle Eastern Division.

The book, Deeb said, illustrates the importance of collecting a wide range of material, even though some material might seem puzzlingly obscure at the time it is gathered. Such material often proves valuable—decades later, in many cases—in ways unimaginable when it was acquired.

For scholars, the book also is useful in ways other than the historical importance of its connection to President Obama. It shows Kenya at a time when it was rapidly evolving technologically, socially, economically and politically. In 1963, four years after the book’s publication, Kenya declared its independence from the United Kingdom.

Volumes such as “Otieno, the Wise Man” also play an important role in the preservation of indigenous languages. UNESCO estimates that half of the more than 6,000 languages spoken today will disappear by the end of the century.

“It is important that at least one place in the world be a repository for those languages,” Deeb said. “When those languages are preserved in a place like the Library of Congress, the whole world thinks more highly of them and wants to preserve them as well.”

July 24, 2013

Hands to the Skies

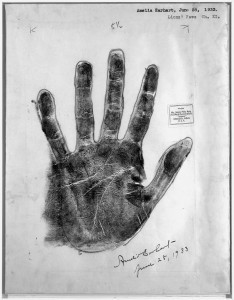

Amelia Earhart. Prints and Photographs Division.

In palmistry, a person’s personality traits, talents and interests are revealed through the topography of his or her hands. Amelia Earhart, born July 24, 1897, had her palm prints analyzed by palmist Nellie Simmons Meier four years before her mysterious disappearance. According to Meier’s analysis, the length and breadth of the famed aviator’s palm indicated a love of physical activity and a strong will. Earhart’s long fingers not only showed her conscientious attention to detail and pursuit of perfection but also revealed her ambitious yet rational nature. Her palm further reflected the reasoned and logistical manner of someone who considers all possibilities before making a decision.

Meier prepared Earhart’s palm print an analysis on June 28, 1933, and you can read it , as part of the Library’s American Memory collections.

Palm of Amelia Earhart. American Memory Collections.

“There is a wide stretch between her thumbs and fingers and between the fingers themselves which, coupled with the shape of the nails, is indicative of an impatience over restraining influence either from individuals or the conventionalities of social life. The diplomacy indicted by the little finger enables her to conform to such restrictions for a certain period, and then the urge for physical and mental activity becomes so strong that she seeks escape by a flight in her plane,” wrote Meier in her 1937 book, “Lions’ Paws: The Story of Famous Hands.”

The digital collections of the Library of Congress contain a wide variety of material associated with Lady Lindy, including manuscripts, photographs and books. This handy guide compiles all the available resources pooled from several Library divisions and collections.

Meier donated her papers to the Library, and the collection includes autographed original palm prints, autographed photographs and character sketches of 135 well-known individuals, including Walt Disney, Susan B. Anthony, George Gerswhin, Mary Pickford and Booker T. Washington.

July 23, 2013

One Scoop or Two

Little girl with ice cream cone in the zoological park, Detroit, Mich. 1942. Prints and Photographs Division.

The weather of late has been particularly hot, and I’m sure many of us have been looking for ways to cool off. Perhaps it’s very appropriate, then, that July is National Ice Cream Month. I’m a rocky road fan, and I love to scoop some ice cream between two warm cookies for a ice cream sandwich!

On this day in 1904, the ice cream cone was invented, according to the July 23 entry from the Library’s American Memory Today in History presentation.

Charles E. Menches and his brother Frank were ice cream purveyors in their hometown of St. Louis, Mo. During the St. Louis World’s Fair, the two were on hand scooping up the sweet confection for the hungry – and hot – masses. On July 23, so much ice cream was being sold at the fair, that the Menches brothers ran out of serving bowls. Next to their tent was pastry-maker Ernest A. Hamwi, who was selling sweet wafer pastries. Needing to come up with another way of serving the ice cream, Charles bought all the pastries, rolled them into cones and began scooping the dessert into them. And, thus according to popular legend, the ice cream cone was born.

It should be noted that no one really knows for sure who made the first cone. Paper and metal cones had been used in Europe for some time, and edible cones were mentioned in French cooking books as early as 1825.

And, if you want to know even more about the sweet treat, including how to make vanilla ice cream courtesy of Thomas Jefferson, you should read this Inside Adams blog post from the Library’s Science, Technology and Business Division.

What’s your favorite ice cream and way to eat it?

July 19, 2013

Witnesses to History, Keepers of the Flame

This is a guest post by Cheryl Fox of the Library’s Manuscript Division

The First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas (July 21, 1861) set many precedents in American history—key troops were transported by train, battle reconnaissance was attempted via observation balloon, battle scenes were sketched and the battle’s aftermath, photographed to be published in newspapers. And word of the results of battle was transmitted via telegraph.

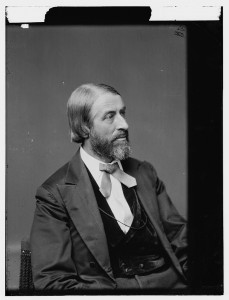

War correspondent and Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Spofford

Two men among the many journalists and battle spectators who observed the battle have special significance for the history of the Library of Congress – - Ainsworth Rand Spofford, correspondent for the Cincinnati Commercial, and John Russell Young, for the Philadelphia News. Both later became Librarians of Congress, Spofford from 1864-1897, and Young from 1897-1899.

Both Spofford and Young transmitted news of the “rout of the Union forces” via telegraph. Young wrote in his article for the News that he had rushed to Manassas Junction, Va. to reach a telegraph line, while Spofford wrote to his wife that he had to use “them legs” to return to Washington to be able to send his report via telegraph. Spofford signed his reports with the pen name Sigma.

Oddly enough, the reason Spofford had an opportunity to become Librarian in 1864 was that his predecessor, physician John Gould Stephenson, was less interested in his library duties than in using his medical knowledge to assist the wounded in Washington, D.C. hospitals, and then as an aide-de-camp to Union officers, notably General Meredith at the battle of Gettysburg.

Stephenson began his tenure as Librarian in June 1861, just one month before the first Battle of Bull Run indicated that the Civil War would be a prolonged and bloody conflict. Stephenson left Spofford in charge of the work of the Library until 1864, when Stephenson resigned. Shortly thereafter, Spofford was officially appointed Librarian of Congress by President Lincoln.

Spofford is credited with taking a tiny Congressional library with a staff of seven and just 82,000 books and convincing Congress to build a new home for it – the Library’s beautiful Thomas Jefferson Building – and place the Copyright Office within the Library. Those steps set the Library of Congress on the path that has made it the world’s largest, most comprehensive library. Today its collections in all formats number more than 155.3 million items.

Trending: Summer Vacation

All across the country, people are traveling for summer vacation. The Library’s collections document this age-old trend.

A contemporary country road in rural America. Photo by Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

HOTEL RESERVATIONS? CHECK. CAR GASSED UP? CHECK. It’s time for summer vacation. Prior to industrialization, people rarely traveled for pleasure, with the exception of the wealthy and those making religious pilgrimages.

The advent of paved roads in the early 1900s helped propel automobile travel in the United States, making cross-country travel possible. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 authorized the construction of the nation’s Interstate System— now totaling more than 47,000 miles. Last summer, Americans traveled more than 520 billion miles on those roads, according to the Federal Highway Administration.

Today most people navigate the highways and byways with the aid of such handy technology as GPS systems and Google maps for their smartphones. But that doesn’t mean that road maps are a thing of the past. State road maps are available free from most states today, thanks to tourism bureaus and automobile clubs.

In 2001, Library map cataloger Charles Peterson donated his personal collection of 16,000 oil company roadmaps to the Library’s Geography and Map Division. With the bulk of material from such maps’ heyday, 1948-1973, the collection complements a substantial collection of similar material dating back to the early 20th century.

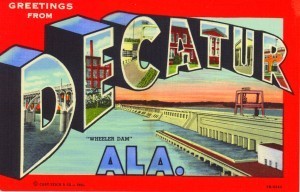

Travel and tourism are well-documented in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division. The Panoramic Photograph Collection features many images of travel destinations such as amusement parks, beaches, fairs, hotels and resorts. Several years ago, the Library’s Junior Fellows Summer Interns discovered novelty postcards located among the copyright deposits and gifts that have come into the nation’s library. A wide variety of travel destinations are represented in this visual format.

A 1946 postcard promotes the Wheeler Dam in Decatur, Ala. Curt Teich & Co., Inc. Prints and Photographs Collection.

The Library’s American Memory collection “By the People, For the People: Posters from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), 1936-1943” includes a variety of artful and colorful posters promoting tourism during the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s.

Noted photographer Carol M. Highsmith has been on the road with her camera, capturing images of present-day California as part of her multi-state “This is America!” project. The images have been donated to the Library and are available, copyright free, to the public (see story on page 27).

This article is featured in the July-August 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

July 17, 2013

Ink-Stained Riches

This year’s casting call for the Library of Congress National Book Festival is complete, and our lineup for the free event Sept. 21 and 22 will include writers Don DeLillo, Joyce Carol Oates and Khaled Hosseini, graphic novelists Lynda Barry, Fred Chao, Jonathan Hennessey, Gilbert Hernandez and Jaime Hernandez, and authors Linda Ronstadt, Christopher Buckley, Stuart Eizenstat, Hoda Kotb, Thomas Keneally, Giada De Laurentiis, and author/photographer William Wegman.

The two-day event, between 9th and 14th streets on the National Mall (from 10 a.m. – 5:30 pm. Saturday and noon to 5:30 p.m. on Sunday, rain or shine) will also offer you an opportunity to nominate “Books That Shaped the World,” which you can also do online at the Festival website.

Check out the site for the authors’ speaking and signing schedules and download the poster by Festival artist Suzy Lee, who will be there to speak and sign posters on Sunday.

Other poets and authors slated to appear at the festival include Katherine Applegate, Marie Arana, Rick Atkinson, Margaret Atwood, Paolo Bacigalupi, Nicholson Baker, Bonnie Benwick, A. Scott Berg, Holly Black, Taylor Branch, Monica Brown, Fred Bowen, Jeff Chu, Susan Cooper, Alfred Corchado, Justin Cronin, Matt de la Pena, Daniel DeSimone, Kathryn Erskine, Richard Paul Evans, David Finkel, Brian Floca, Amity Gaige, Eric Gansworth, Cristina Garcia, Albert Goldbarth, Alyson Hagy, Mark Helprin, Kevin Henkes, Juan Felipe Herrera, John Hessler, Jennifer and Matthew Holm, Kay Bailey Hutchison, Sheila Miyoshi Jager, Oliver Jeffers, Pati Jinich, Adam Johnson, William P. Jones, Cynthia Kadohata, Jamaica Kincaid, Matthew J. Kirby, Jon Klassen, Kirby Larson, Grace Lin, Mario Livio, Rafael López, Kenneth W. Mack, William Martin, Ayana Mathis, D.T. Max, James McBride, D.J. MacHale, Heather McHugh, Lisa McMann, Terry McMillan, Brad Meltzer, Wesley Granberg-Michaelson, Elizabeth Moon, Christopher Myers, David Nasaw, Phyllis Reynolds Naylor, Kadir Nelson, Patrick Ness, Katherine Paterson, Richard Peck, Benjamin Percy, Tamora Pierce, Daniel Pink, Andrea and Brian Pinkney, Matthew Quick, Lesa Cline-Ransome and James Ransome, Vaddey Ratner, Veronica Roth, Christel Schmidt, Jon Scieszka, Chad “Corntassel” Smith, Andrew Solomon, Sonya Sones, Walter Stahr, Manil Suri, James L. Swanson, Mark Teague, Evan Thomas, U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey, Steve Vogel, Rick Yancey, Dean Young, Charles Whelan and Henry Wiencek.

The 2013 Library of Congress National Book Festival will give you a chance to meet and hear firsthand from your favorite poets and authors, purchase books and get them signed, have photos taken with PBS storybook characters and participate in a variety of activities. More than 200,000 people were estimated to have attended the festival in 2012.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers