Library of Congress's Blog, page 171

August 23, 2013

March on Washington Riches at the Library of Congress

Celebrants observing the 50thanniversary of the March on Washington should not miss special displays of artifacts, treasures and a talk by Congressman John Lewis on Wednesday, Aug. 28, all at the Library of Congress and all free and open to the public.

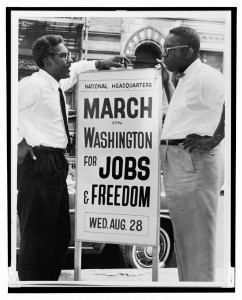

March on Washington organizer

Bayard Rustin

Opening that day is the Library’s photo exhibition, “A Day Like No Other, Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington” featuring photos of the 1963 march by photographers including Leonard Freed, ‘Flip’ Schulke, Danny Lyon and Roosevelt Carter. That exhibition will be open from 8:30 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. in the Graphic Arts Galleries on the ground floor of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, 10 First St. S.E., directly east of the U.S. Capitol building. Curators will be on hand to enhance the viewing experience, and Brigitte Freed, the widow of featured photographer Leonard Freed, will also be on hand for this exhibition opening.

Also on Wednesday, Aug. 28, several other special activities are planned:

A talk by Congressman Lewis at 10 a.m. in the Library’s Great Hall on the first floor of the Jefferson Building;

A special display, from 11 a.m. – 2 p.m., of unique treasures from the Library’s collections related to the March on Washington, in the foyer of the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium on the ground floor of the Jefferson Building. These will include a copy submitted for copyright registration of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and manuscripts and photos related to iconic participants’ roles in the march;

Additional photos, legal materials, audiovisual displays and music of the day in the Library’s ground-floor Whittall Pavilion, plus a guest book for visitors to sign. Those who do will receive a button that is a reproduction of a button worn by participants in the 1963 march;

A noon panel discussion in Dining Room A on the 6th floor of the Library’s James Madison Building at 101 Independence Ave. S.E. (just south of the Jefferson Building) about March on Washington organizer Bayard Rustin. This talk is cosponsored by the Library’s Daniel A.P. Murray Association, and the Library’s chapters of Blacks in Government (BIG) and GLOBE, a staff group representing a gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender membership.

The Library of Congress holds a great wealth of research material pertaining to the African-American experience. Among its holdings are the NAACP Records, which are the largest single manuscript collection at the Library, and the most-accessed; the papers of such activists as Roy Wilkins, Moorfield Storey, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Joseph Rauh, Mary Church Terrell, Jackie Robinson and Thurgood Marshall; and the papers of James Forman, Herbert Hill and Tom Kahn.

August 21, 2013

Inside the March on Washington: Bayard Rustin’s “Army”

(The following is a guest post by Kate Stewart, processing archivist in the American Folklife Center, who is principally responsible for organizing and making available collections with Civil Rights content in the division to researchers and the public.)

(left to right) Bayard Rustin, deputy director, and Cleveland Robinson, chairman of Administrative Committee, March on Washington. Orlando Fernandez, World Telegram & Sun photo. Prints and Photographs Division.

The planning and execution of the March on Washington in 1963 stands as an extraordinary testament to the vision, political strategy and determination of several organizations and key individuals, chief among them A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, who had conceived of just such an event as far back as the 1940s. By the summer of 1963, the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership, an umbrella group of member organizations including the SCLC, the NAACP, the National Urban League and SNCC, among others, had come together to raise funds to support the day-to-day work of Rustin and his production crew, consisting of dozens of college students.

Typically, it is the voices of leaders of the groups within the council – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young – that figure prominently in many accounts of the march. By contrast, this second post in a series commemorating the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington focuses on the experiences of individuals who worked behind the scenes to plan and carry out a feat of logistics, imagination and organization that made the march an indelible memory for both those who participated in it and others who witnessed it on television around the nation and the world. In these two interviews from collections in the American Folklife Center, Rachelle Horowitz and Joyce Ladner describe their work at the march headquarters in Harlem in the summer of 1963. Both remember the long hours and hard work it took to plan the march in the course of eight weeks, and both talk about the mentorship of Bayard Rustin, for whom they worked that summer.

Rustin’s central role in shaping the philosophy of the movement and organizing many of the key direct actions that gave the movement public prominence was indisputable. By the summer of 1963, he had already planned and carried out the Prayer Pilgrimage in 1957 with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), as well as two marches in 1958 and 1959 called the Youth March for Integrated Schools. All three of these events were precursors to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in the summer of 1963.

Rachelle Horowitz was a student at Brooklyn College in the late 1950s when she became involved in the Civil Rights Movement. She started volunteering with a little-known organization called In Friendship in Manhattan with Rustin and Ella Baker, another civil rights icon, and subsequently, at age 22, became the march’s transportation coordinator. In this 2003 interview with Megan Rosenfeld for the Voices of Civil Rights Project Collection, Horowitz discusses how Rustin led the planning of the march in 1963 at the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership, along with A. Philip Randolph. Despite initial opposition from the Kennedy administration and other politicians, Rustin and Randolph convinced them to approve the march. Horowitz then talks about the challenge of chartering buses and planning the logistics of moving thousands of people in and out of the city in August 1963.

[media player not shown]

Sisters Joyce and Dorie Ladner grew up in Mississippi and became civil rights activists as teenagers in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). While attending Tougaloo College, Joyce joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced “snick”), a group founded in 1960 by students involved in sit-ins, protests and other forms of nonviolent direct action. In the summer of 1963, Joyce went to New York as a representative of SNCC to help plan the march along with her sister, Dorie. Joyce worked as a fundraiser with Rustin, Rachelle Horowitz and Eleanor Holmes (now Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton). The two sisters lived with Horowitz and Holmes for the summer. In this anecdote from an interview conducted by UNC’s Southern Oral History program for the Civil Rights History Project Collection, Joyce remembers long hours, hard work and “Bobby” Dylan hanging out in their apartment and playing guitar late into the night when the residents only wanted to go to sleep.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/jaladn...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

The Library of Congress exhibition “A Day Like No Other: Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington” opens on Aug. 28. You can read the first post of the “Inside the March on Washington” blog series here.

August 19, 2013

“West Side Story” Redux

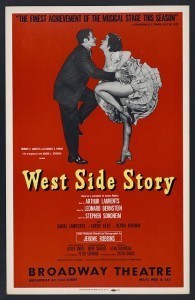

“West Side Story,” 1958. Printed by Artcraft Litho. & Ptg. Co. Inc. Prints and Photographs Division.

On August 19, 1957, “West Side Story” began its pre-Broadway tour at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C. About a month later, it opened on Broadway, changing the nature of the American musical and challenging the country’s view of itself. The show dealt seriously with violence, adolescent gangs and racial prejudice—themes rarely included in musicals—and ended with one of the show’s leads dead on stage. The integration of music, dance and script, as well as the theatricality of the staging were a revelation to audiences.

The musical’s success must be credited primarily to its creators. Composer Leonard Bernstein created his most memorable score—complex, passionate, tuneful, shocking and bursting with rhythmic energy. Jerome Robbins, credited with conceiving the show, doubled as director and choreographer. Lyricist Stephen Sondheim, in his first Broadway musical, exhibited the wit, intelligence and craft that would make him the pre-eminent songwriter of his generation. Arthur Laurents staged the adaptation of William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” in contemporary Manhattan with a lean, concise libretto, which allowed for the integration of language, music, dance and movement. All of these elements came together to create a groundbreaking musical.

If you missed the opening by a few decades, you can still see the online exhibit. “West Side Story: Birth of a Classic,” drawn mostly from the Library’s extensive Leonard Bernstein Collection, offers a rare view into the creative process and collaboration involved in the making of this extraordinary production. Included in the exhibition are unique items such as an early synopsis and outline of the script; Bernstein’s annotated copy of “Romeo and Juliet”; choreographic notes from Robbins; two original watercolor set designs by Oliver Smith; original music manuscripts; a facsimile of a Sondheim lyric sketch for the song “Somewhere”; and amusing opening-night telegrams from celebrities such as Lauren Bacall, Cole Porter and Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

Also included are notes that reveal actors who auditioned, such as Jerry Orbach and Warren Beatty, who was described as “good voice—can’t open his jaw—charming as hell—clean cut.” As an added bonus, the Library has the very first prints made of several never-before-seen production photographs taken for Look magazine for a feature spread that never ran.

The composer, conductor, writer and teacher Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) was one of 20th-century America’s most important musical figures. The Leonard Bernstein Collection is one of the largest and most varied of the many special collections held by the Library’s Music Division. Its more than 400,000 items, including music and literary manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, audio and video recordings, fan mail and other types of materials extensively document Bernstein’s extraordinary life and career.

August 16, 2013

Inquiring Minds: Alan Lomax Goes North

(The following is a guest post by Guha Shankar, folklife specialist with the Library of Congress American Folklife Center.)

A fall landscape of orange and red foliage rushes by a car winding down a long road…a stern-faced singer draws his bow across a single-stringed lute and sings a ballad in Serbian about the 1389 Battle of Kosovo… an elderly couple softly recite Finnish hymns in the parlor of their home…a man and woman trade French song verses in call and response style by the fading light of day.

These sounds and images are only a few of the astonishing range of roots music and cultural communities in the American Upper Midwest that were recorded 75 years ago this week for the Library of Congress by Alan Lomax, legendary folk song collector and then assistant in charge of the Library’s Archive of Folk Song. It is just as eye-opening that the 23-year-old Lomax set out on his pioneering tour of Michigan, the “most fertile source” for folk songs in the summer and fall of 1938, alone in a Library car. He had with him little else but his recording kit, which consisted of an instantaneous disk cutting machine, dozens of blank disks and remarkably, a 16mm film camera. He returned to Washington after three months on the road with nearly a thousand recorded songs and several hundred feet of motion picture images (sadly, several rolls of film were stolen on a stop during the expedition and never recovered).

Now, on the 75th anniversary of that trip, the American Folklife Center, which houses the Alan Lomax Collection, and several institutions are jointly commemorating the journey. The two film clips below are excerpted from a longer documentary that, together with my colleague, Jim Leary, University of Wisconsin folklorist and noted cultural historian of the region, I produced and edited for the Library of Congress. The documentary marries the all-too-brief silent film footage that Lomax shot to audio disk recordings of the same performers; the microphone can clearly be seen in the shot on several occasions. But, given the absence of any recording logs or other notation about the filming and what music was being played at that exact moment, the choice of the audio track that I joined to the picture is based solely on reasonable conjecture, decided upon by Leary. On several instances, I slowed the film frame rate severely in the digital editing system to accommodate a few more seconds of audio. Jim Leary is also producing a set of archival recordings of the region’s musical communities culled from the Library’s Lomax collection that will include more than 40 full-length tracks from Lomax’s 1938 trip.

In this first clip, Lomax filmed the Floriani family, a Croatian tamburitza group that also played more popular styles of music, in the front yard of their home in Ameek, Mich. It is a town in the “Copper Country,” which is a reference to mining, the main industry in that part of the state. There are several shots of a mine in the first part of the clip under which the song “31st Level Blues” is playing. It is about mine work – “31st level” refers to the depths that miners have to descend to do their jobs – and the lyrics amplify the hard toil and weariness of the occupation and the antagonism that characterized relations between mine workers and bosses. The second song highlights the group’s facility as tamburitza performers and the track used here is a traditional Croatian ballad, “Majko Moje” (My Mother)

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/lomaxd...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'smallWide'

}

The second clip features Mose and Exilia Bellaire, French-Canadian residents of Hancock, Mich., singing “Dites moi pourquoi un?” It is a version of “The Carol of the Twelve Numbers,” which has been documented throughout Europe and North America as far back as the mid-nineteenth century.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/lomaxd...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'smallWide'

}

The 75th anniversary projects also include a series of podcasts produced by the Library, a potential e-book, “Michigan-I-O,” slated to be published by Dust to Digital Records, as well as public programming consisting of lectures and concerts, a traveling exhibition, and the dissemination of recordings to the communities in Michigan. In addition to the Library, participants in the projects include the Michigan State University Museum, Michigan Council for the Humanities, the Great Lakes Traditions Endowment; the Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Culture at the University of Wisconsin, the Association for Cultural Equity (ACE), and the Finlandia Foundation.

Keep an ear and an eye out for more such performances in the days and weeks ahead, drawn from the American Foklife Center’s Archive.

August 15, 2013

A (Married) Life at the Opera

It’s a fair thing to say that classical music, and more specifically opera, is what brought me and my husband together. We met while working at The Denver Post, but our first date – seeing Verdi’s “Un Ballo in Maschera” at Opera

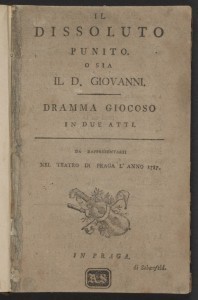

An early “Don Giovanni,” dubbed “a playful drama in two acts”

Colorado – may have been a sort of test. He didn’t want to marry anyone who wasn’t into opera, and I wanted someone who wouldn’t squirm at the sound of “squeaky violins and tinkly pianos,” as one of my ex-boyfriends once described classical.

We’ve seen symphonies, chamber-music concerts and yes, operas in our quarter-century together. Mostly operas. Shortly after we moved to the Washington, D.C. area I got him season tickets for opera as a birthday present. We just kept going. It’s been wonderful!

We’ve seen — no pun intended — scores of operas, including multiple bites at my two favorites, Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro” and Richard Strauss’ “Der Rosenkavalier.” And the exhibition “A Night at the Opera” that the Library of Congress is opening today will probably get visited, repeatedly, by my spouse because it’s heavy on items by his two favorite opera composers: Giuseppe Verdi and Richard Wagner, both of whom are observing 200th-birthday celebrations this year.

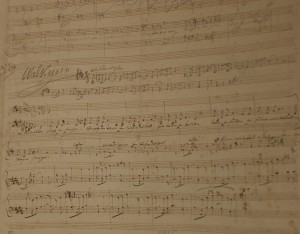

If opera gets inside your head – even at the Bugs Bunny/Elmer Fudd level – you’ll really enjoy this exhibition. It displays several manuscripts in the composers’ own hand – one from Verdi’s opera “Attila” and another from Wagner’s “Walküren” (The Valkyrie); a third from Alban Berg’s “Wozzeck” and letters — from Berg to fellow composer Schoenberg and from Puccini to Alfredo Vandini. It can inspire awe to be a few inches away from something these greats actually touched.

And the exhibition features programs and the stage manager’s original score from George and Ira Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess,” from the Library’s unparalleled Gershwin collection.

There are also many beautiful visuals: first editions of opera scores (including a 1787 piano-vocal score from Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” and the full score from Wagner’s “Lohengrin”) and photos of some of opera’s greatest stars through history, from Enrico Caruso (as Radamés in “Aida”) to Lauritz Melchior (as Lohengrin) to Marian Anderson as Ulrica in “Ballo”) to Lily Pons as Lakmé and Alexander Kipnis as the title character in “Boris Godunov.”

Speaking of Boris, there is a wonderful wall-size rendition of the coronation scene from “Boris” and there are gorgeous set designs, in watercolor, by Oliver Smith for his 1960s productions of “Carmen” and “Don Giovanni.” The exhibit also features the original Galileo Chini set design for Puccini’s “Turandot” from 1926.

The Library of Congress has superb music collections, and this exhibition brings forward the cream of its huge opera holdings. Don’t miss it!

August 14, 2013

Inside the March on Washington: A Time for Change

(The following is a guest post by Kate Stewart, processing archivist in the American Folklife Center, who is principally responsible for organizing and making available collections with Civil Rights content in the division to researchers and the public.)

For many Americans, the calls for racial equality and a more just society emanating from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963, deeply affected their views of racial segregation and intolerance in the nation. Since the occasion of March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 50 years ago, much has been written and discussed about the moment, its impact on society, politics and culture and particularly the profound effects of Martin Luther King’s iconic speech on the hearts and minds of America and the world. The Library of Congress exhibition “A Day Like No Other: Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington” which opens on Aug. 28, is an opportunity to both celebrate the occasion and to renew the discussion about the ideals that underpinned the march and the broader struggles for freedom.

This post is the first in a series that will explore the “insider” perspective on the march as experienced by individuals who helped organize or in some other way helped shape the events leading up to Aug. 28, 1963. In popular consciousness, the march has come to stand as the symbolic high point of the Civil Rights Movement and a testament to the fundamental goals and aspirations of all who participated in the broader struggle. However, when seen through the eyes of those who organized and participated in the event, more complicated and nuanced appraisals emerge, regarding the march itself as well as the broader political, social and cultural context surrounding it. In particular, those who had fought for racial equality and social justice “in the trenches” of the segregated South viewed the march as yet another moment in which to press their demands for permanent change, as well as a strategic opportunity to continue to fight against the status quo. In the two following interviews from collections in the American Folklife Center, on-the-ground activists (who were college students at the time), reflect on the historical and political circumstances in which the march was planned.

Sisters Joyce and Dorie Ladner grew up in Mississippi and became civil rights activists as teenagers in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). As a student at Jackson State University, Dorie was expelled for participating in a civil rights demonstration. She then went to work for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, commonly pronounced “Snick”), a group founded in 1960 by college students who challenged segregation through sit-ins at restaurant counters, protest marches and other forms of non-violent direct action. In the interview excerpt, she discusses the physical harm and brutality that front-line activists endured during the summer of 1963 – jailing, beatings and even murder – leading up to the march in August. Joyce Ladner describes her shock and sorrow at hearing about the murder of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, a friend since childhood, and her subsequent decision to move to New York to work with her sister and others to plan the march.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/afc201...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

Courtland Cox was a student at Howard University in Washington, D.C., when he helped found the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG) to protest segregation in the D.C. area. Members of NAG soon joined with other student groups across the nation to found SNCC. In these excerpts, Cox recalls internal tensions and differences among student activists over the tactics and strategies to use in pressing for social change, particularly the principles and philosophies of non-violent protest, which were espoused by John Lewis and other student leaders. He then recalls how, in 1962, he and fellow Howard students Stokely Carmichael and Tom Kahn staged a protest in Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s office because of Kennedy’s refusal to speak with them about fellow Howard student, Dion Diamond, who had been falsely charged and jailed in Louisiana for organizing protests there. In Cox’s perspective, the hope that activists had for meaningful change after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 and the Kennedy election in 1960 waned and turned into outright confrontation by the time of the march, due to the federal government’s “go slow approach” to desegregation.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/afc201...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

August 13, 2013

Last Word: Rep. John Lewis and the March on Washington

(The following is an interview from the July-August 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

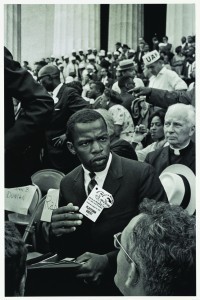

John Lewis, then leader of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, rises to speak at the March on Washington in 1963. Detail ©Bob Adelman, Prints and Photographs Division.

Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) discusses his memories of the March on Washington and its legacy.

You were one of the leaders of the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Aug. 28, 1963. Tell us about some of your experiences that day.

On the morning of the march, I traveled with the other speakers to Capitol Hill and met with Democratic and Republican leaders of the House and Senate. We met with the chairman and ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee. Then, we traveled to the Senate and also met with the majority and minority leaders. We discussed the need for strong civil rights legislation from the Congress.

After we left Capitol Hill, our plan was to link hands and lead the marchers from Capitol Hill down Constitution Avenue to the Washington Monument. We thought there might be a few thousand people, but in the end there were over 250,000. When we came out to the street, I looked towards Union Station and saw a sea of humanity marching. I said to myself, there goes our people, let me catch up to them. We linked arms and started marching with the crowd. They literally pushed us down the street, toward the memorial and onto the stage.

That day, I spoke sixth and Martin Luther King Jr. spoke last. His speech was amazing. He turned the marble steps of the Lincoln Memorial into a modern- day pulpit. We did not have a sense of the magnitude of that day, at the time, but he knew—and we knew—he had made an impact. After the speeches were over, people were still coming to the National Mall from all over America. We were invited to the White House by President Kennedy. He met us at the door of the Oval Office and he was standing there almost like a beaming father. He shook hands with each speaker and said to each one, “You did a good job.” And when he got to Dr. King he said, “And you had a dream.”

Your book “Across That Bridge” shares life lessons for those committed to bringing about social change. What are some of those lessons?

The movement taught me to have faith, to never give up, to always love and to not become bitter or hateful. Most importantly, it taught me to pace myself for the long haul. The struggle for equality will not last a week or a year; it is the struggle of a lifetime.

Your soon-to-be published book, “March,” is in the form of a graphic novel. Why did you choose to use this format to tell the story of the Civil Rights Movement?

The format was chosen to reach more young people and children, so they can know the history and meaning of the Civil Rights Movement. It is an attempt to bring the movement alive through drawings and words.

Do you believe President Obama’s election is the realization of Dr. King’s dream?

The election of President Obama is a significant step towards making Dr. King’s dream become a reality, but it is not the true fulfillment or realization of his dream. It is only a down payment on King’s dream of building a “Beloved Community”—a society based on simple justice that values the dignity and the worth of every human being. We have come a long way, down a very long road toward accomplishing this ideal, but we are not there yet. We still have a great distance to go before we realize the true meaning of Dr. King’s dream.

Civil rights leader John Lewis is the U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district. Rep. Lewis is the author of “Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of a Movement,” “Across That Bridge: Life Lessons and a Vision for Change” and “March,” a graphic novel about the Civil Rights Movement.

MORE INFORMATION

Listen to Rep. John Liews at the 2004 and 2012 National Book Festivals.

August 9, 2013

InRetrospect: July Blogging Edition

The Library’s blogosphere kept things cool in the July heat with a variety of posts representing the wealth and breadth of the institution’s collections and initiatives. Here are just a few selections.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Ben-Hur and Music to Race Chariots By

Robin Rausch talks about musical adaptations of Lew Wallace’s well-known book.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

Stinky Flowers

D.C. goes wild over the “corpse flower.”

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

A Duel with Rifles

A debate in early 19th century Congress leads to a tragic end.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

3 Things to Change the World for Personal Digital Archiving

Bill Lefurgy offers advice on making digital archiving easier for today’s society.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Our Favorite Posts: Crossing the Delaware: General George Washington and Primary Sources

The blog looks back on a post about Washington’s 1776 crossing of the Delaware River.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

A Summer Holiday in the Isle of Wight

Jeff Bridgers beats the July heat by looking at some photochroms in P&P’s collections.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

Always a Laureate

Rob Casper talks about Natasha Trethewey’s first year as Poet Laureate.

August 8, 2013

The “Essential” Opera

There are so many things about the upcoming Library of Congress exhibition, “A Night at the Opera,” that I feel personally connected to. Several of the operas highlighted in the 50-item display are like a program of operas I have sung in my last few seasons as part of The Washington Chorus.

Set design for Puccini’s “Turandot” by Galileo Chini. Music Division.

Each season, we usually do a program of “essential” compositions by a composer. And, in the past, we’ve highlighted the works of Giacomo Puccini and Richard Wagner – both maestros featured in the exhibition, which opens next Thursday.

On display for the first time in the exhibition is a colorful set design by Italian Art Nouveau artist Galileo Chini (1873-1956), created for the very first production of Giacomo Puccini’s “Turandot” at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan in 1926. I had the opportunity to sing this opera when the chorus included selections from all three acts as part of our “Essential Puccini” concert. The legend of a bloodthirsty princess whose icy, vengeful heart softens as she comes to know true love was brought to life with musical grandeur, with the chorus keeping pretty busy throughout, as Puccini wrote much for an accompanying ensemble.

“A Night at the Opera” also will commemorate Wagner’s bicentennial He was born in 1813. He’s actually one of my favorite composers, so being able to sing some of his works has been a particular treat. The exhibition features a holograph manuscript (in the composer’s own handwriting) score of his “Siegfried Tod,” from which the scheme for his four-opera cycle, “Der Ring des Nibelungen,” developed. Handwritten on the manuscript leaf amongst the music notes is “Walküren” or “Valkyries.” I actually had the opportunity to view this manuscript a couple of years ago and then sang selection’s from Wagner’s Ring Cycle, including “Ride of the Valkyries,” for another Washington Chorus program, the “Essential Wagner,” last season. So, you could say, things came full circle for me.

This original Wagner manuscript leaf shows an early sketch for his four-opera cycle “Der Ring des Nibelungen.” Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

I just really love full, formidable and somewhat overwhelming music, and both of these operas have it in spades. And, the thing about both of them, too, is that even if you don’t know much about these operas or the genre itself, you’ve likely heard and are familiar with some of the music. That should make checking out the upcoming exhibition even better.

“A Night at the Opera” opens Thursday, Aug. 15, in the Performing Arts Reading Room. You can read more about it here.

August 7, 2013

LC in the News: July Edition

News of Library of Congress acquisitions and initiatives led the headlines in July, with stories on the recent donation of the Lilli Vincenz papers and work of the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation to preserve television.

“History is written by the victors, but also by the scrapbookers, the collectors, the keepers, the pack rats. By those who show up, at the beginnings of things and with the right technology,” wrote Washington Post reporter Monica Hesse. “In one corner of the climate-controlled manuscript division, on a series of otherwise empty shelves, sits Lilli Vincenz’s unprocessed collection. … Twelve boxes. Cream-colored. Heavy. Inside: meticulous fragments of the gay rights movement of the latter half of the 20th century.”

Also running pieces were The Blade, The Associated Press (in the Las Vegas Sun), advocate.com and the Huffington Post.

“Preserving these shows turns out to be a challenging and time-consuming task. But unless the videotapes are transformed, experts say, future generations will have a diminished appreciation of the era of JFK, flower power and Watergate” wrote Washington Post reporter W. Barksdale Maynard on the Packard Campus.

CBS This Morning’s Jan Crawford reported on the facility’s efforts as well.

News of the Library’s exhibition, current and upcoming, also made the media spotlight.

Opening Aug. 15 is “A Night at the Opera,” an exhibition featuring 50 items celebrating the musical art form.

“Open the shrine!” wrote The Washington Examiner, quoting Wagner’s “Parsifal.” The story also featured a 13-picture slideshow to accompany the article.

Also running brief announcements were the Associated Press, San Francisco Chronicle and Washington Post.

The Library’s “The Gibson Girl’s America” exhibition, which opened in March, was highlighted in the Washington Post Express (June 27).

“With her arched eyebrows, corseted waist and elaborate updo, the Gibson Girl could have come off as stiff. But in Charles Dana Gibson’s iconic illustrations, which graced the pages of Life, Scribner’s and other magazines at the turn of the 20th century, she was vivacious, athletic and smart,” wrote reporter Sadie Dingfelder.

Where Magazine also highlighted the exhibition and the Library in its July 2013 issue.

In a headline not to be missed, “Busy Babies at the Library of Congress,” the Washington Post took a trip to the Library’s Great Hall in the Thomas Jefferson Building to enjoy its art and architecture.

“Washington D.C. is not exactly known as a laugh-riot city, and certainly not through its very serious marble sculpture. But it turns out the Library of Congress — of all places —offers something of a respite from that reputation,” wrote reporter Valerie Strauss. “On a recent trip to the library, I was amused by the sculpted baby boys — known as putti in Italian Renaissance art. … It is said, according to one of the tour guides, that the sculptor, Philip Martiny, was asked to sculpt putti in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance (as the building itself is designed). Martiny said he didn’t want to sculpt little Italian babies in an American building in the nation’s capital, but felt it was only right to create strong American babies who were busy and industrious. And so he did.”

Also continuing to make the news were announcements regarding teachers selected for the Library’s Teacher Institutes. Local coverage came from Pennsylvania, Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, West Virginia and Connecticut.

And in a last piece of interesting news, The Huffington Post took several of the Library’s Civil War stereographs and made them into animated gifs.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers