Library of Congress's Blog, page 169

October 22, 2013

Inquiring Minds: Sabor! Latin American and Hispanic Cookbooks in the Library of Congress Collections

Natalia Silva Prada

(The following is a guest post by Kaydee McCann, humanities editor for the “Handbook of Latin American Studies” and reference librarian in the Hispanic Division.)

Historian Natalia Silva Prada is a visiting researcher in the Hispanic Division of the Library of Congress. Supported by a fellowship from Goya Foods, she spent two months preparing an annotated bibliography of Latin American and Hispanic cookbooks from the Library’s collections. The bibliography will be made available in the coming months on the Hispanic Division website. She is continuing research in the Hispanic Division, writing a book on the role of political lampoons and political prophecies in 16th- to 18th-century Latin America.

Q: Why do you think there’s been a recent surge of scholarly interest in food history?

The growing interest in the history of gastronomy is really tied to two related subdisciplines – social history and cultural history. Social history took hold in the first half of the 20th century and cultural history reached a peak in the 1990s. The academic interest in the daily lives and experiences of ordinary people and in popular culture has recently been matched by a popular interest in food, cooking, restaurants and so forth. And you can see this interest reflected in the many television shows about cooking competitions and chefs, for example. So there’s been a sort of meeting of scholarly and popular interest.

Q: How many individual cookbook titles did you find during your research? And how many titles did you include in your bibliography?

There were many more titles in the Library on the food and cooking of Latin America and United States Hispanics than I expected to find. I located 1,300 titles and included 200 in the final bibliography. (I had two months to work on the bibliography, which placed some limits on the numbers of books that I had time to review and include).

Q: How did you decide which ones to include?

It seemed to me that it would be really interesting for people to know about the historical works from each country, so I included some of the oldest books. At the same time, I thought it would be really useful to highlight some of the most recent gastronomic works, so I looked for titles published between 1990-2012. I didn’t completely exclude works from other periods. For example, about two-thirds of the titles I included on Surinamese cooking were published in the 1970s.

Q: The Library has an incredible wealth of resources. How did you begin your research?

Before beginning a new project, a researcher has to do some investigation into previous bibliographic studies to understand which works are the best and what remains to be done. Earlier works help you understand what and how to search: specific terms and subject headings, specific concepts, specific authors. Bibliographic reviews are another essential tool for preselecting materials, for example the books that are indexed in the databases available at the Library of Congress and the abstracts in the “Handbook of Latin American Studies.”

Q: Food can be a way to maintain and preserve culture, and it can also be an indication of the influences that different cultures have on one another. Was there an identifiable moment when Latin American cooking emerged, as something new and separate from Spanish and Portuguese cooking?

Rice in a lunch of a sugar worker on a Puerto Rican plantation. 1942. Prints and Photographs Division.

And similarly, was there a moment when Hispanic/Latin American food-related influences began to find their way into mainstream U.S. tastes?

From the very first moment, when European and African populations made contact with the American continent, the foundations were established for new types of foods, new choices of food, new patterns of consumption and cooking. New tastes evolved and food taboos were broken as they tried new foods. European, indigenous, and African traditions all made a mark on New World cooking and eating.

As for the United States and Mexico, you could say that they have shared flavors and tastes since the early days when California and the Southwest states were part of the Spanish colonies. That sharing has continued right up to the present day – the use of chiles to preserve meat, for example, isn’t a tradition that belongs to just one nationality. Then, at the end of the 19th century, due to the Spanish-American War, Cuba and Puerto Rico began to interact with the United States and that marked another period of the spread of different foods and ways of cooking.

A similar situation occurred as Latin American migrants to the United States continued cooking and eating the foods from their own countries, which little by little were then adopted by North Americans. During the second half of the 20th century, there was a proliferation of [Latin and Hispanic] restaurants and many Hispanic dishes have been popularized by the fast food chains.

Q: Your recent work has looked at political dissent in the colonies under Spanish rule. Do you see any connections between food and political dissent in the colonial context?

A page from the Huexotzinco Codex showing the turkeys, chiles, and corn paid in tribute to Spanish Crown in the 16th century by the peoples of Huexotzinco. Library of Congress

Well, at first it didn’t seem to me that there was any connection between food and political discord, but if you consider the social discontent at the root of many rebellions, then you do see links between a lack of food (corn, for example), social discord and political dissent. And if you look at the abuses of colonial authorities, such as unlawful imposition of taxes or excessive tax increases on provisions, or changes in the rules related to the supply of food and provisions, then you do find these connections. And the resulting protests over this unfair taxation probably helped [the colonists] recognize what was rightfully theirs and to see themselves as different from the Spanish.

Q: Food styles change over time. For example, in the United States, there’s been a growing interest in local and organic foods, and we’ve seen the rise of the farm-to-table movement. Did you see any trends in the cookbooks that you reviewed?

In the most recent cookbooks, there’s a growing recognition of the use of organic foods and interest in recipes featuring organic foods and also an interest in the recovery and preservation of local food traditions.

In the Andes, particularly in Bolivia, there’s been a strong emphasis on recovering the use of grains, like quinoa, that were eaten by pre-Hispanic indigenous populations. Other countries, especially Mexico and Paraguay, are also showing this interest in preserving local food traditions. Cooking and health are also very closely linked these days, for example, with recipes for people with diabetes.

Q: What surprised you most or impressed you most over the course of your research in the Library of Congress?

I was impressed by the indigenous populations of Mexico who eat insects and poisonous grasses and also by the many recipes from Nicaragua using tortoises; the latter really had an impact on me. Also quite striking were the food offerings made to the saints. Although I already knew about this tradition in Mexico, it’s also quite prevalent in Brazil. There are also books on music and food and on food as an aphrodisiac.

Tortilla making. Between 1950 and 1970. Prints and Photographs Division.

Q: In addition to your work as an historian, you’re a blogger. You have two blogs, one on political culture in the New World and one that explores Latin American food history . Were any of your posts inspired by research that you did at the Library?

Yes, all of the posts on the blog “Love Cooking, Love History,” are based on research done at the Library of Congress with the support of the Goya Fellowship. From reading this enormous number of books, I developed lots of ideas and noted many things of interest that I wanted to explore in greater depth. Whenever I’m not feeling inspired, I just look over the introduction to my bibliography once or twice to remember the amazing things that might be of interest to the blog readers. The best example is one of my most recent entries about entomofagy or the art of eating insects, as I called it!

Q: You grew up in Colombia, received your doctorate and taught for many years in Mexico, lived in Italy, and now live here in the U.S. Are there any foods that hold special memories for you?

I was born and raised in Colombia and lived there for almost 27 years. Besides the influences from Mexican food, the friends I had in Mexico, who were from all over Latin America and from Italy, also had an important impact. From them and, in particular from my Italian husband, there have been many cultural influences.

The food I miss the most is from my country, Colombia. I especially miss the tamales santandereanos. And from the years I lived in Italy, I miss the delicious pizzas, the hams, the gelato. Strangely enough, now that I live in the United States, I eat more Mexican food than ever because the “Americanization” of it is more to my taste – it’s a little less spicy and a little more “friendly” for my relatively intolerant palate.

Q: Your husband is also a researcher here in the Hispanic Division. Who’s the chef in your family?

Well, my husband was really the one who inspired me to cook – I learned to cook for love. When we met, he cooked a little bit more than me, but over time I became the chef of the house! I was also inspired by a book that my mother gave me when I left Colombia – “La buena mesa,” by doña Sofia Ospina de Navarro – and for which I have great affection. With that little book I started to experiment with Colombian recipes and from my husband and a few good friends, I learned to make excellent pasta! For my own wedding reception, I made a tuna soufflé that was a great success and from then on I was really excited by cooking.

For more information on foods native to the Americas and on food history and cooking, see the following guides produced by the Science and Business Division of the Library and links to gastronomy collections in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division:

How the squash got its name

Chocolate: a resource guide

Food Writing: a resource guide

Rare Book Collections on cooking and gastronomy

Katherine Golden Bitting Collection

Elizabeth Pennell Collection

September 27, 2013

A Congressional Legacy: The Peter Force Library

1865 portrait of Peter Force / Mathew Brady, Prints and Photographs Division.

Purchased through an act of Congress in 1867, the Peter Force Library became the foundation of the Library’s Americana collections.

As the nation sought to reconstruct the Union after the Civil War, so, too, did the Library of Congress seek to build a collection that documented fully America’s history. At the time, the nearly 100,000 volumes in the Library of Congress fell short of the task.

“It is not creditable to our national spirit to have to admit the fact … that the largest and most complete collection of books relating to America in the world is now gathered on the shelves of the British Museum,” wrote Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford in his “Special Report” to Congress’ Joint Committee on the Library, dated Jan. 25, 1867. Spofford appealed to the committee to approve the purchase of the private library of Peter Force. The report ends with an appeal “to the judgment and liberality of this committee and of Congress to secure the chance of adding to this National Library the largest and best collection of the sources of American history yet brought together in this country.”

The response was quick and unanimous. A recommendation to appropriate the sum of $100,000 would be made to the full Congress. President Andrew Johnson’s signature, five weeks later, made it law.

Born in New Jersey, Peter Force (1790- 1868) was the son of a Revolutionary War soldier. A lieutenant in the War of 1812, Force settled in the nation’s capital where he worked as a printer, newspaper editor and politician—serving as mayor of Washington, D.C., from 1836-1840.

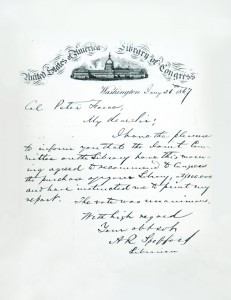

In this letter, dated Jan. 26, 1867, Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford informs Peter Force that the Joint Committee on the Library has recommended the purchase of his private library. Library of Congress Archives, Manuscript Division

But at his core, Force was a collector and editor of historical documents. His life’s work was the compilation of a “Documentary History of the American Revolution,” better known as the nine- volume “American Archives.” The manuscript materials acquired by Force to compile the work were part of his personal library. Spofford observed, “The value to the Library of Congress, which is wholly destitute of manuscripts as unpublished materials for history, would be very great.”

All told, Force’s private library comprises more than 60,000 items relating to the discovery, settlement and history of America. With the acquisition of the collection, the nation’s library, in one stroke, established its first major collections of 18th-century American newspapers, incunabula (pre-16th-century publications), American imprints, manuscripts and rare maps and atlases. The 420 manuscript items in the collection include several autograph journals of George Washington. The 245 bound volumes of pre-1800 American newspapers cover the Stamp Act controversy, the Revolutionary War and the establishment of the U.S. Constitution.

With the acquisition of Force’s library, the Library of Congress also acquired a perfect copy of Eliot’s Indian Bible (1663), the first complete Bible printed in America. Several years ago, a member of Congress requested this item for his swearing-in ceremony. This congressional request and many others underscore Thomas Jefferson’s belief that “there is no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer,” which was one of the justifications for the congressional purchase of Jefferson’s eclectic personal library in 1815.

This article is featured in the September-October 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

September 25, 2013

Inquiring Minds: An Interview with History Prize Recipient Danielle Johnson

Paul Ridgway, Danielle Johnson (center) and Nanette Ridgway at the “Discovery or Exploration in History Prize” ceremony. National History Day.

Earlier this summer, the Library of Congress awarded the first “Discovery or Exploration in History Prize” as part of National History Day (NHD) to Danielle Johnson of Faiss Middle School in Las Vegas. Johnson was honored for her project, “The Erie Canal: ‘A Little Short of Madness.’” The prize is sponsored by the Elizabeth Ridgway Fund, established two years ago in memory of the former director of Educational Outreach at the Library of Congress. Ridgway, who served in that position for seven years, died in 2010 of injuries suffered in a fall while horseback riding. She was 41.

Q. Tell us about your research project on the Erie Canal and how/why you became interested in that particular subject?

I first became interested in the Erie Canal when I saw it on the sample topic list for the 2013 National History Day theme, “Turning Points in History.” I had heard of the canal before, but I didn’t really know what it was so I was eager to learn about it. I also felt a connection to the topic because my grandparents lived in Erie, Penn. Out of the [project] options of performance, documentary, exhibit, website and paper, I was drawn to the exhibit because it allows more hands-on learning and shows more creativity. Along with the display, each student/group had to create a process paper showing how their research had been transformed into the project and an annotated bibliography that cited all of the sources used and the importance of each source.

Q. Your research led you to the Library of Congress. What collections and/or items did you find most informative?

The Library of Congress was the first place my teacher suggested for sources and was where I found my first primary source. This source was a letter written by Abraham Lincoln concerning the Erie Canal. In his letter, Abraham Lincoln said he had chosen a certain engineer to enlarge the locks on the canal. Later, I found another letter written by the New York legislature to the president asking him to decide on the engineer that would enlarge the locks on the Erie Canal to keep the people safe. I realized this letter was the original letter sent to President Abraham Lincoln. This was interesting to see the involvement of New York and the president because the Erie Canal was built entirely by New York State, not the government. Another source I used from the Library was a portrait of DeWitt Clinton. DeWitt Clinton was the man in charge of the whole Erie Canal project, so the portrait helped show others the driving force behind the canal.

Q. What did you learn about the canal that you may not have previously known? Any interesting discoveries found through your research?

Because I created a project on a topic I knew nothing about at the beginning of the year, I became an expert on my topic by the end of the year. This was because I had no limits to my research. My goal was to know more about my topic than anyone else, so I went to every source I could find and learned everything I could. Everything I learned throughout the project was new information. I learned everything from the speed limit of the boats to the worker wages. My favorite discovery towards the end of my research was the quote, “America can never forget to acknowledge that they have built the longest canal in the world, in the least time, with the least experience, for the least money, and to the greatest public benefit,” by William Stone. This quote completed my project. It made the whole thing make sense and showed why the Erie Canal was a turning point in history. Although America was so inexperienced in engineering, they made this amazing canal that helped the country in so many ways, including expanding west, improving transportation and creating jobs.

Q. How did you feel when you were awarded the first “Discovery or Exploration in History Prize” from the Library?

That was just pure excitement. I already knew I hadn’t won for the junior individual exhibit category or outstanding state entry, so this was my last chance to win – not only for me but for Nevada, too. Nevada had quietly sat through nearly three hours of other states running on and off stage, so when the “Discovery or Exploration” award came up on the screen, we were on the edge of our seats. Once my name was called we all just freaked out. I hugged my teacher and ran down to the stage while my mom was crying and cheering at the same time she was trying to record me. I have no idea what I was thinking when I was getting the award other than, “Oh my gosh!!!!” I was just very excited to have won an award at a national competition my first year participating in National History Day (NHD). This was such an amazing award to win because of the backstory of it and Elizabeth Ridgway.

Q. Why do you think it’s important for people to have an understanding and appreciation of history?

I believe it is important for people to have an understanding and appreciation of history because it is the reason we are who we are. It’s our ancestors, our roots and our heritage. History shapes us into the people and the country we are. It’s just like America was shaped by the Erie Canal. America went from a young, inexperienced country to a wiser and more knowledgeable country because of all of the events and history that has happened to it.

Q. Why do you think it’s valuable for the Library to preserve such historical collections, and what do you think the public should know about using them and doing research here?

It’s valuable for the Library to preserve historical collections for research projects just like NHD so people can learn more about their project topics or anything that interests them by using the many primary sources the Library has available. The Library of Congress is the most reliable source website out there and it has information on almost anything you could imagine.

More information about National History Day, the annual contest and all prizes is available at www.nhd.org.

September 23, 2013

Celebrating Hispanic Heritage: The Voice of Hispanic Literature

(The following is a guest post by Catalina Gomez of the Library of Congress Hispanic Division.)

The Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape, most commonly referred to as the AHLOT, is one of those rare gems that readers can come across in the hidden corners of the Library of Congress. Compiled and carefully curated by the Hispanic Division since the 1940s, this extensive audio archive has collected close to 700 recordings of the most prominent poets, novelists and essayists from the Luso-Hispanic world reading from their works. Throughout the years, the AHLOT has captured works in Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, Dutch, Catalan, Basque, Nahuatl, Zapotec and Aymara, becoming a unique treasure of the cultural patrimony of Spain, Portugal, Latin America, the Caribbean, the United States and the world.

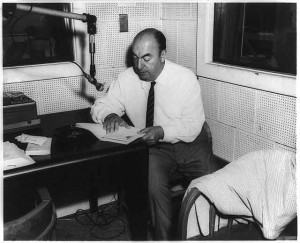

Pablo Neruda, recording for Library of Congress in its recording studio. Prints and Photographs Division.

Among the writers included in the archive are Nobel Prize winners Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia), Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda (both from Chile), Miguel Angel Asturias (Guatemala), Octavio Paz (Mexico), Juan Ramón Jiménez, Vicente Aleixandre, Camilo José Cela (all from Spain), and Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru). Other noteworthy authors included are Argentinians Jorge Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar, and Mexicans Elena Poniatowska and Carlos Fuentes. Cuban-American poet Richard Blanco, who read his poem “One Today” in the 2013 presidential inauguration, was recently recorded and added to the collection in the spring of 2013.

Listening to Neruda read his beloved poem “Las Alturas de Machu Picchu” (“The Heights of Machu Picchu”), Paz read his “Piedra Nativa” (“Native Stone”), or Mistral read “Canción Qechua” (“Quechua Song”), will suffice in making one understand the magic of these recordings, which are available for the public to listen to in the Hispanic Reading Room of the Library. The idea behind the AHLOT has been to provide poets and prose writers with a unique space and opportunity to interact intimately with their work, where they can express it, and, in some cases, dissect it. As they record, writers choose which selections to read from, in what order to do so and what tone to use – hence the uniqueness and value of each session. Another fundamental aspect of the archive is the great significance of a literary work when read aloud. It could be said that in the voices of these writers live the essence of their creation in its purest form.

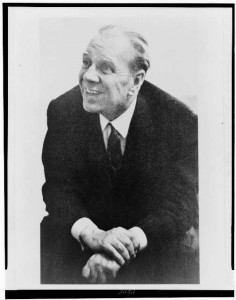

Jorge Luis Borges. 1962. Prints and Photographs Division

In a great number of AHLOT recordings, authors provide rich reflections on the meaning of their work. Borges, for example, speaks about the concepts of happiness and the profound nature of poetry during his recording: “… it might be said that to a poet unhappiness is essential.” He says, “Happiness, as you all know, is an end in itself. Happiness does not desire anything more. But to have been unhappy, to be unhappy, is something that a poet has to turn… has to change into music, into passion, into some strange harmony.”

Novelist Cortázar explains how surrealist cinema and reading anthropology fuel his creativity, and how John Keats has been one of his most influential figures (translated from the Spanish): “I oftentimes imagine that Keats is still alive and that he is my buddy.” Cortázar also gives advice to young writers during his recording (translated from the Spanish): “I would offer some advice to young writers, and that is to never ask for advice from other writers. I would advise them to search alone and through reading … reading books. My advice is for them to search for that indirect advice that can only come from a poet that has long been dead, or by a philosopher far, far away. Never ask another writer for advice, as that is a sign of weakness, and those who ask for advice will never become great writers.”

Even though the bulk of the recordings in the AHLOT are literary, the archive also delves into other disciplines such as philology, history, essays and non-fiction. The recording of Angel María Garibay (Mexico), an encyclopedic compiler, biblical scholar and expert on Nahuatl and ancient Greek is one example. Garibay’s recording contains commentary on his important philological study of the Aztec languages, and he reads Nahuatl poetry both in its original language and in Spanish. Another example of a rare recording is that of Lewis Hanke, the first chief of the Hispanic Division of the Library of Congress, and the founding editor of the “Handbook of Latin American Studies” (HLAS). In his AHLOT interview, Hanke tells the story of the beginnings of the Division and of the building of the beautiful Hispanic Reading Room.

Building this collection has been no easy feat. In 1943, the then assistant chief of the Hispanic Division, Francisco Aguilera, spearheaded the project, and for 27 years he served as the curator of the AHLOT before passing it on to the Hispanic Division’s current chief, Georgette Dorn. Aguilera and Dorn, throughout their years as curators, have actively reached out to authors, poets, publishers and embassies, in order to cast a wide net and capture as many voices as possible.

Staff members of the Hispanic Division are currently working with the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division (MBRS), to transfer the recordings from their original format (magnetic tape reels) to digital form – a task made possible thanks to the cutting-edge technology housed in MBRS’s Culpeper campus. The goal of the Hispanic Division is to one day provide this special collection to an online audience making it available to the entire world. For now, those who live locally or those who come to visit the nation’s Capital can come and experience the collection onsite in the historic Hispanic Reading Room of the Library of Congress.

September 20, 2013

If You Build It, They Will Learn

(The following is a story written by Daniel De Simone, curator of the Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection in the Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division, for the September-October 2013 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. You can download the issue in its entirety here.)

Booker T. Washington, circa 1905-1915 | Harris & Ewing Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

The year 1912 was a pivotal one for African American educator Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) and Chicago businessman Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932). The two men were acquainted, with Washington as the founder and principal of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute for the training of black teachers (now Tuskegee University) and Rosenwald serving as a member of the school’s Board of Trustees.

That year, Washington had the idea to build schools for African American children throughout the rural South. “Separate but equal” was the law of the land, but black children were learning in underfunded and dilapidated buildings across the South. Why not replicate the success of Tuskegee by providing the necessary academic skills in clean, well-lit modern structures for students on the K-12 level? For funding, he turned first to Tuskegee’s benefactors.

Rosenwald, the president of Sears, Roebuck and Co., was approaching his 50th birthday and had decided to celebrate by donating funds to various causes. He shared Washington’s concern about the lack of educational resources for black children in the South. He had already launched a program to offer matching grants for the construction of African American YMCAs and was interested in Washington’s plans to do the same for schools.

In a letter to Washington dated July 15, 1912, Rosenwald offered to help.

“If you had $25,000 to distribute among institutions which were offshoots of Tuskegee or doing similar works to Tuskegee, how would you divide it?”

Washington replied five days later in a long and heartfelt letter.

Julius Rosenwald, 1917 | Harris & Ewing Collection, Prints and Photographs Division,

“I shall be very glad to send you recommendations and opinions regarding the use of $25,000 in helping institutions. … Such a sum of money will prove a Godsend to those institutions and can be made to accomplish much more good just now than any one realizes. I think I am not stating it too strongly when I say that a wise expenditure of such a sum of money will enable these schools to do fifty or one hundred percent better work than they are now doing.”

Rosenwald requested from Washington a list of schools that “in your judgment should participate, naming the amount for each and the purpose for which the money is to be used … and as soon as any school you name has raised an equal amount, I will pay to it such an amount as you have designated.”

Both men shared a belief in the importance of self-reliance. So it is not surprising that the plan called for monies from the Rosenwald Fund to be matched by the African American community. The call was met and exceeded.

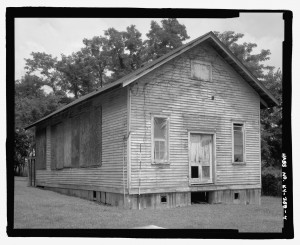

Cadentown Rosenwald School, Lexington, Ky., 2004 | Dean A. Doerrfeld, Historic American Buildings Survey/ Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, Prints and Photographs Division

Washington pushed the concept further by suggesting that “the people themselves build the [school] houses…” The design for the Rosenwald Schools was simple – a two-room schoolhouse with plenty of windows to aid in lighting and ventilation. Their modern construction stood as a symbol of black aspiration and potential.

After Washington’s death in 1915, Margaret Murray Washington continued to work with Rosenwald in her late husband’s stead. At the program’s conclusion in 1932, it had produced 4,977 new schools, 217 teachers’ homes, and 163 shop buildings. It is estimated that the schools served more than 663,000 students in 883 counties in 15 states.

Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision declaring racial segregation unconstitutional, the Rosenwald Schools became obsolete. Many of the structures were repurposed to serve other community functions while others were abandoned. In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the Rosenwald Schools to its list of America’s Most Endangered Historic Places, and declared the building program as “one of the most important partnerships to advance African American education in the early 20th century.”

September 19, 2013

One Day, 15 Hours, 53 Minutes and Counting …

Pavilions arise … the Library of Congress National Book Festival opens Saturday

The Library of Congress National Book Festival is just hours away!

It’s free … it’s open to the public on the National Mall … and it’s got fun and fascination for readers of all ages and tastes.

No fewer than 112 stellar authors – historians, novelists, children’s and teens’ authors, poets, biographers, illustrators and graphic novelists – will delight legions of fans at the 13th annual Festival. It takes place on Saturday, Sept. 21 and Sunday, Sept. 22, 2013, between 9th and 14th streets on the Mall. It will run from 10 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. on Saturday and from noon to 5:30 p.m. on Sunday, rain or shine.

Special features of this year’s festival include a Library of Congress Pavilion packed with presentations from the Library’s curators and collections, plus a presentation of top awards Sunday at noon in the Special Programs Pavilion for 5th-and 6th-grade students who wrote essays in the multi-state “A Book That Shaped Me” contest. During that session, a trio of excellent literacy programs that have won awards in the premiere Library of Congress Literacy Awards will be announced.

In keeping with the festival’s theme, “Books That Shaped the World,” fans are invited to go to the official website and, using a survey form, nominate books that they believe meet that description. Balloting will also take place in-person at the Festival’s Library of Congress Pavilion (you can even nominate on our giant whiteboard).

Poets, authors and artists slated to appear at the festival include Marie Arana, Rick Atkinson, Margaret Atwood, Lynda Barry, Taylor Branch, Christopher Buckley, Fred Chao, Giada De Laurentiis, Don DeLillo, Stuart Eizenstat, Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Juan Felipe Herrera, Khaled Hosseini, William P. Jones, Cynthia Kadohata, Thomas Keneally, Hoda Kotb, this year’s poster illustrator Suzy Lee, Rafael López, Terry McMillan, Brad Meltzer, Joyce Carol Oates, Katherine Paterson, Tamora Pierce, Daniel Pink, Linda Ronstadt, Jon Scieszka, Chad “Corntassel” Smith, Manil Suri, U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey, George Weigel, William Wegman … well, heck. Why not just look at the entire list of authors here.

This may be, honestly, as much fun as you’ll ever have under the auspices of the federal government (paid for with funds provided by very generous sponsors). Don’t miss it! It goes on rain or shine, and every now and then there will be some precip, so pack a little umbrella or a poncho and you’ll be golden.

We’ll see you there! Meanwhile, have fun watching the NBF countdown clock (and other features) at the festival website.

A Pirate’s Life For Me

Morrison’s production of the new romantic melo-drama, “The Privateer,” by Harrison Grey Fiske. 1897. Prints and Photographs Division.

Today, you best get out your peg leg, eye patch and practice your “arrrr’s” … it’s International Talk Like a Pirate Day! What started as a joke among a handful of friends in 1995 has become a widely recognized fun-for-the-sake-of-fun celebration, thanks in large part to a column written by Dave Barry in 2002.

A few words of advice from various Internet resources in preparation for the day: growl and scowl often, making sure to slur words and gesticulate frequently while using pirate lingo. Embellish stories at will and, above all else, be loud and confident.

And, fear not, your social media needs are covered as Facebook has “pirate” as an official language.

Pirates were certainly colorful characters and the scourge of the sea. During the centuries of Spanish exploration and colonization, “treasure fleets” made regular trips to the Americas to deliver merchandise and collect treasures and precious metals. As these cargos increased in size and value, so did the risk of capture and theft. Foreign navies, privateers (commissioned agents sent out against the enemies of states), and pirates threatened, attacked and plundered the ships of the treasure fleets. Privateers were licensed by a government to raid the ships of declared enemies and shared their gains with the licensor. Pirates were not loyal to any country and attacked indiscriminately for their own gain.

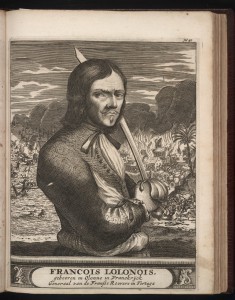

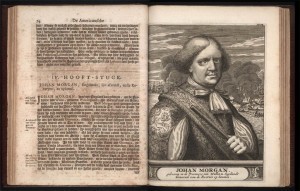

One of the most important books documenting pirates was “The Buccaneers of America,” written by Alexandre Exquemelin in 1678. He served as surgeon for nearly 10 years with various buccaneers and gives an eyewitness account of the daring deeds of French, Dutch and English pirates raiding Spanish ships and colonies in the Caribbean.

This item is one of many digitized materials from the Library’s Jay I. Kislak Collection housed in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. You can get an up-close and personal look at this priceless volume here.

And, what would a pirate be without a song? Several types of sea shanties and sailors’ songs are found in the recorded collections of the Archive of Folk Culture in the Library’s American Folklife Center. In addition, recordings can be found in the Library’s American Memory collections.

And, what would a pirate be without a song? Several types of sea shanties and sailors’ songs are found in the recorded collections of the Archive of Folk Culture in the Library’s American Folklife Center. In addition, recordings can be found in the Library’s American Memory collections.

September 17, 2013

Happy Constitution Day!

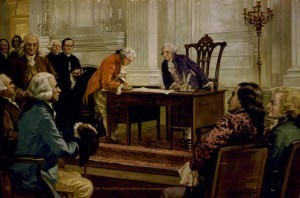

Reproduction of a painting of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and others signing the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia, Penn., by Hy. Hintermeister. 1925. Prints and Photographs Division.

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Today we celebrate the 226th anniversary of the signing of the United States Constitution in Philadelphia, Penn. The Constitutional Convention convened in response to dissatisfaction with the Articles of Confederation and the need for a strong centralized government. Although the vote was close in some states, the Constitution was eventually ratified and the new Federal government came into existence in 1789.

And, to mark the historical occasion, the Library of Congress is releasing a web publication and free “app” for smart devices that places a clause-by-clause explanation of the important document in the hands of millions of people.

The new resources, which include analysis of Supreme Court cases through June 26, 2013, will be updated multiple times each year as new court decisions are issued. Legal professionals, teachers, students and anyone researching the constitutional implications of a particular topic can easily locate constitutional amendments, federal and state laws that were held unconstitutional, and tables of recent cases with corresponding topics and constitutional implications.

Release of the web publication and app also coincide with the 100th anniversary edition of a printed document, “The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation,” which was published at the direction of the U.S. Senate for the first time in 1913. Popularly known as the Constitution Annotated, the volume has been published as a bound edition every 10 years, with updates addressing new constitutional law cases issued every two years. The analysis is provided by the Congressional Research Service (CRS) at the Library of Congress. These new resources will now make the nearly 3,000-page Constitution Annotated more accessible to more people and enable updates of new case analysis throughout each year.

While the Constitution serves as a model of compromise and collaborative statesmanship, the road to it was a slow and difficult process – most of which took place during a long revolutionary war. The Library’s online exhibition, “Creating the United States,” takes a look at the path in creating one of our nation’s most fundamental documents. Included is an interactive that let’s viewers connect with particular phrases and ideas, along with edits made when drafting the document.

September 15, 2013

Celebrating Hispanic Heritage Month: Why Sept. 15?

(The following is a guest post by Barbara A. Tenenbaum, specialist in Mexican culture in the Library of Congress Hispanic Division.)

It seems a bit strange that in contrast to all the other “heritage” celebrations and recognitions, the one for Hispanic Americans starts in the middle of the month – September 15 to be exact. That selection, however, has profound roots in Hispanic history.

The vast majority of Hispanics living in the United States come from Mexico and Central America. Those areas are deeply connected to that date because their independence day is either on September 15 or September 16.

Originally, Mexico (much larger than it is today, including Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona and parts of several other states) and all the nations of Central America except Panama – Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua – were all part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Spanish Crown had ruled the Viceroyalty of New Spain for almost 300 years when its Mexican residents began to think about becoming a co-equal kingdom or independent from the mother country. The Bourbon Reforms (1766-1804) had brought with them new taxes, new restrictions on native-born Spaniards, and the exile of the Jesuit order among other things. Further, many Mexican residents wanted to trade freely and legally with other powers like Britain, France, and the United States.

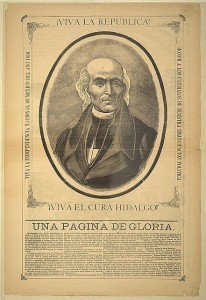

Commemoration of Father Miguel Hidalgo by José Guadalupe Posada. Prints and Photographs Division.

At midnight on the night of Sept. 15, 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla began his campaign for Mexican independence and rang the church bells in the town of Dolores in the present-state of Guanajuato, Mexico, proclaiming, “Viva la independencia y mueran los gachupines!” (Long live independence and death to the Spaniards!”) Hidalgo knew he would soon be arrested along with other co-conspirators who had been discovered by the authorities and decided to advance the process by beginning the movement immediately. At its height, the Hidalgo insurgency had approximately 50,000 members, most of whom were Indians.

Royalist forces eventually defeated and captured Hidalgo and his supporters, but others continued the movement, including José María Morelos, Guadalupe Victoria and Vicente Guerrero. On Feb. 24, 1821, royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide adopted the independence cause and issued the “Plan de Iguala,” calling for independence from Spain, the adoption of Roman Catholicism as the state religion, and the legal equality of whites and mixed races. Ultimately, Mexico and Central America became independent from Spain in 1821.

Iturbide declared himself emperor in December 1821 and Central America agreed to become part of royalist Mexico. However, Iturbide was forced to abdicate the throne in March 1823, and the countries of Central America left Mexico in July, with the significant exception of Chiapas. Those nations declared September 15 as their Independence Day, while Mexico went with September 16, to mark when Hidalgo delivered his famous “Grito de Delores” battle cry of independence.

September 13, 2013

Back to School

(The following is the cover story written by Stephen Wesson, educational resource specialist in the Educational Outreach Division of the Office of Strategic Initiatives, for the September-October 2013 edition of the Library of Congress Magazine. You can download the issue in its entirety here.)

Teachers and students are discovering new ways of learning with resources from the Library of Congress.

Fourth-grade students enjoy looking for clues in historic maps. Educational Outreach Division.

Students in the Bronx pore over first-hand accounts of riots in New York City in 1863 and map them to neighborhoods that they know today.

In Oregon, fifth-graders sprawl across a massive world map from 1507, searching for clues about what life would be like for an explorer.

A Nevada middle-schooler finds original paperwork from the construction of the Erie Canal— including a letter from Abraham Lincoln—weaves it into the story of labor and management in the industrial revolution, and wins a national history prize.

These students from different states, in different grades, studying different subjects, have one thing in common: They’re all making discoveries using resources from the Library of Congress.

Over the past two decades, technology has allowed the Library to make many of its collections accessible in classrooms around the world, helping teachers and students to explore a wide variety of subjects. The Library’s robust educational outreach program helps educators maximize this opportunity. At the heart of that program is the unparalleled collection of objects and documents that anyone can explore, save and use for free on the Library’s website, loc.gov.

Bringing the Library into the Classroom

Students from Georgetown Day School in Washington, D.C., use the LOC Box to explore different features of the Library’s architecture. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

The Library’s outreach to K-12 educators has its roots in the late 1980s, when Librarian of Congress James H. Billington recognized that digital technology could be used to make the contents of the nation’s library more accessible to Congress, the American people and the world. In the 1990s, the Library began digitizing items from its collections and sending them to schools on disc. With the rise of the Internet, the treasures of the Library, and its expertise, could be available to an even wider audience. The possibilities for teachers and students were—and are—tremendous.

However, these technologies bring new challenges as well. Students need the skills that will allow them to navigate a crowded information marketplace, and the skills to prepare them to be effective 21st-century citizens. Meanwhile, teachers need materials and strategies to engage students and provide them with opportunities to learn and practice problem-solving, research and collaboration skills.

In the current educational climate, primary sources are more important than ever. The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) require teachers to use primary sources in their classrooms, supporting students as they learn to cite evidence and synthesize ideas, thoughtfully considering each piece of information’s point of origin. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), a guide for the teaching of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), also stress the value of primary-source analysis and research skills.

“The Library is playing a unique and vital role in supporting the K-12 community during this period of transformation,” said Lee Ann Potter, the Library’s director of Educational Outreach. “As the world’s largest cultural repository, the Library provides free access to millions of online primary- source items.”

The Power of Primary Sources

Kindergarten students from Manalapan, N.J., interact with primary sources. Photo by Earnestine Sweeting.

The power that these items bring to learning is that they are historical artifacts that were created during the time period under study. Primary sources are the raw materials of history and culture. “As such, they capture students’ attention,” said Potter. “They give students a powerful sense of history and of the complexity of the past in a way that textbooks and other secondary sources don’t. Analyzing primary sources prompts students to ask questions; guides them toward higher-order thinking, better critical-thinking and analysis skills; and encourages additional research.”

No matter the subject or era, there’s something for everyone. From Thomas Edison’s late 19th-century films to 20th-century soda commercials, from poet Walt Whitman’s notebooks to the journals of scientist Carl Sagan, from Revolutionary War letters from Valley Forge to the stories of Iraq War veterans, the collections span the universe of knowledge, and offer a dazzling record of human creativity.

An Online Home for Teachers

The Library’s support for educators isn’t limited to providing access to its collections.

“We are providing the nation’s K-12 educators with a treasure trove of free tools, professional development and subject-area expertise that allows them to bring the world’s history and culture to life in their classrooms,” said Potter.

All this can be found at the Library’s online home for educators—loc.gov/teachers. The Teachers Page provides classroom-ready primary sources, along with tools and training that make it easier to integrate sources effectively into curricula. The site also allows K-12 educators to interact and share ideas and to learn from Library staff members via webinars.

The site offers more than 100 carefully prepared, teacher-tested lesson plans and teaching activities built around the Library’s online collections. The collections are all searchable by Common Core State Standards, state content standards and the standards of national organizations.

To keep up with everything the Library is doing for teachers, more than 25,000 subscribers receive the Teaching with the Library of Congress blog (blogs.loc.gov/teachers). The blog brings ready-to-use teaching ideas and news to its audience via email and RSS feeds.

Educators looking to build their skills can choose from an array of online, self-directed training modules or customizable professional-development activities on the Teachers Page.

When in doubt, teachers and students can pose their questions through the Library’s online “Ask a Librarian” service.

“Looking ahead, we are energized by the possibilities that mobile devices offer cultural institutions like the Library of Congress, which seek to serve broad and diverse audiences, regardless of where they are located,” said Potter.

On-Site Opportunities

Teachers participate at an on-site workshop at the Library of Congress. Educational Outreach Division.

Each year, educators from across the country are selected to participate in one of several week-long Teaching with Primary Sources Summer Teacher Institutes held at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. (Apply at the Library’s “Resources for Teachers” website.) To provide educators across the country with similar instruction, the Library’s Teaching with Primary Sources (TPS) Educational Consortium offers professional development workshops in various locations.

Teachers and elementary-school students who plan to visit the Library in person should not miss the Young Readers Center. They also will find that many of the Library’s exhibitions offer special guides for children to interact with the exhibitions. Student groups in grades four to six can participate in the LOC Box program to “unlock” the secrets of the historic Thomas Jefferson Building and learn about the Library of Congress and its resources. The program allows students to participate in hands-on activities designed for use by a team of students led by a teacher or adult chaperone.

Anyone age 16 or older can get a Reader Identification Card to do research at the Library of Congress. The reader card allows the public to access the more than 155 million items in the Library’s collections.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers