Library of Congress's Blog, page 165

January 29, 2014

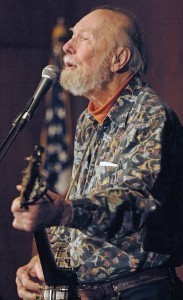

Remembering Pete Seeger

Folk singer, activist and friend of the Library of Congress Pete Seeger passed away Monday in Manhattan. He was 94. The Library’s American Folklife Center and the Music Division are home to multiple collections documenting Seeger and his family’s extraordinary musical accomplishments.

(The following is a repost from the American Folklife Center blog, Folklife Today.)

Pete Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014)

January 28, 2014 by Stephen Winick

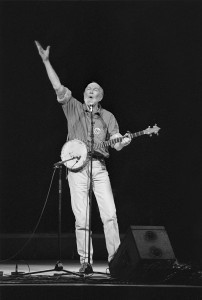

Photo by Robert Corwin, AFC Robert Corwin Collection

On behalf of the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, I’m sad to pass along the news of the death of Pete Seeger, a longtime friend of the AFC Archive and a giant in the folk music world, one of the most significant American folk musicians ever. Many AFC staff members have personal reminiscences of Pete, which we’ll be gathering in the days to come. Meanwhile, we wanted to place online an appreciation of all he has done for folk music and for AFC. We have extensive collections relating to Pete and his family, but that’s only one part of his meaning for us.

Pete Seeger was part of an important musical family, the son of ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger and concert violinist Constance de Clyver Edson Seeger. He was exposed to folk music as a young child, when his parents took him on a musical expedition in a homemade trailer, designed to bring classical music to rural areas. John Seeger, Pete’s older brother, remembered the family’s experience at AFC’s 2007 symposium:

[Charles] said, ‘I’m going to take good music to the countryside, because they cannot afford orchestras, they cannot afford quartets…. So he spent a year and a half building that damn trailer! What happened was, in western North Carolina, spending a winter there…at every farm he would say, ‘can my wife and I play you some music on Saturday?’ And after their music was over, the local farmers would say, ‘now, would you listen to our music?’ Every farm we went to, everyone could either play an instrument, or could sing, or could harmonize…and they all knew the songs! What was he bringing music to the countryside for? In March, as soon as the snow was gone, we all piled in the trailer, and we tore home, and he went to New York to teach!

The Seegers get ready to leave Washington, D.C. for their “trailer trip” in 1921. Pete, at 18 months old, holds his mother’s hand.

Pete’s love of folk music stemmed from such childhood experiences. When he was seven years old, his parents divorced, and his father later remarried, to the composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, who was also an important transcriber and arranger of folk music. With both father and stepmother involved, his love for the music blossomed in his teenage years, and he began singing songs and learning to play the ukulele. In 1936, he returned to western North Carolina with Charles and Ruth, and attended the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, organized by local folklorist and performer Bascom Lamar Lunsford. There he heard the five-string banjo for the first time, and decided to learn to play it.

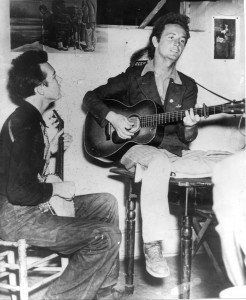

Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, circa 1940. This image was likely taken in Oklahoma City during a trip Pete and Woody made from Washington, D.C., to Pampa, Oklahoma. Courtesy of Guy Logsdon.

In the 1930s, Pete was invited by his friend Alan Lomax to work at the Library of Congress Archive of American Folk Song, which is now the AFC Archive. There’s no record of his being paid, so we consider him the Archive’s first intern! Several AFC collections from the 1930s and 1940s contain materials collected by Lomax and Seeger, as well as music and square-dance calls performed by Seeger alone and with groups.

In the early 1940s, Seeger began performing with The Almanac Singers, a group that also featured Woody Guthrie. According to Pete, who told the story onstage at the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium during the Seeger Symposium concert in 2007:

Woody must have thought I was a queer duck. He was seven years older than I was. He said, ‘That Seeger is the youngest man I ever knew. He don’t drink, he don’t smoke, and he don’t chase girls.’ But I had a good ear and I could accompany Woody on every single song. So I tagged along with him for a while.

Although they got their start as both pro-labor and anti-war activists, the Almanac singers realized the importance of defeating Hitler, and Seeger wrote a song about that, entitled “Dear Mr. President,” which was also the title track of an Almanac Singers album. He performed the song for the Library of Congress in January or February 1942 under the pseudonym of Pete Bowers; hear that recording here.

Pete Seeger entertaining at the opening of the Washington, D.C. labor canteen, 1944. Note First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in the crowd.

After service in World War II, Seeger continued his work as a musician, and rose to fame initially with the Weavers, a group founded on the model of the Almanac singers, but with fewer songs of protest and a more polished, nightclub-ready sound. The Weavers had several hits, especially a version of “Goodnight Irene,” which was a number-one hit in 1950. That song had been adapted by Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, from a version he learned from his uncle Bob; the AFC archive has recordings of Lead Belly and his Uncle singing the song. The Weavers’ career ended in 1953 due to the blacklist, although they did play reunion concerts on occasion after that. The Weavers also served as primary inspiration for the Kingston Trio, the group that sparked the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, as well as countless other similar groups, from the Limelighters to the Clancy Brothers, making Pete Seeger one of the founding fathers of the whole American folk scene.

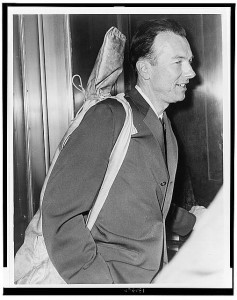

Pete Seeger arrives at Federal Court with his guitar over his shoulder, April 1961. World Telegram photo by Walter Albertin.

In 1955, Pete answered a subpoena to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He refused to plead the Fifth Amendment (which admitted the possibility that his testimony might incriminate him) and instead asserted a First Amendment right not to speak:

I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this.

For this he was convicted of contempt of Congress in 1961, a conviction that was overturned a year later. At his sentencing, he said:

I have been singing folksongs of America and other lands to people everywhere. I am proud that I never refused to sing to any group of people because I might disagree with some of the ideas of some of the people listening to me. I have sung for rich and poor, for Americans of every possible political and religious opinion and persuasion, of every race, color, and creed. The House committee wished to pillory me because it didn’t like some few of the many thousands of places I have sung for.

AFC and the Library of Congress have produced online content in recent years on Pete Seeger and the Red Scare, including a lecture by David Dunaway and an essay by Stephanie Hall.

Despite these troubles, Seeger continued his career as an important songwriter and folksong specialist. He wrote “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” with AFC archivist Joe Hickerson, and “If I Had a Hammer” with Lee Hays. He changed the lyric of “We Will Overcome,” to “We Shall Overcome,” creating a beloved spiritual of the Civil Rights movement, and wrote the song “Turn! Turn! Turn!” based on Bible verses. He popularized many traditional folksongs, such as “Kumbaya,” giving them new, political connotations. All these songs were hits for various popular folksingers. He also helped popularize the five-string banjo through his own music and by writing an important instruction book and recording, which were made into an instructional film; AFC has original film elements and other original footage from this and other Seeger films.

Pete and Toshi Seeger, 1985. Photo by Robert Corwin, AFC Robert Corwin Collection.

Pete’s legacy can’t be understood without taking into account his wife Toshi, whom he married in 1943 and whom he always credited as making his career possible. In addition to other forms of support, Toshi was a gifted filmmaker, and during the 1960s the Seegers made wonderful films together, documenting traditional music and culture around the world, which they donated to the AFC archive in 2003. In 2006, AFC director Peggy Bulger and reference librarian Todd Harvey interviewed both Pete and Toshi, and you can read an article based on the interview in Folklife Center News. Toshi passed away last year, a few days shy of their 70th wedding anniversary.

In addition to his work as a singer and songwriter, Pete Seeger was an activist for civil rights and environmental causes, especially in the Hudson Valley area of New York. He was founder of the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater organization and other charities and foundations. AFC’s Civil Rights History Project interviewed him in 2013 about his work in that field, and we plan a blog post highlighting this interview soon.

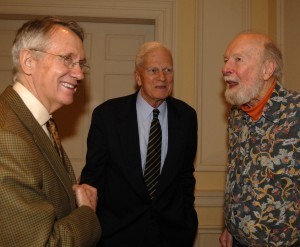

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington, and Pete Seeger at AFC’s Seeger Family Symposium, March 16, 2007. Photo by Robert Corwin, AFC Robert Corwin Collection.

Although Seeger had trouble with his voice in his 80s and 90s, he continued to perform, leading singalongs on many songs. His grandson Tao, a top folk musician, often toured with his grandfather, as well as singing and playing guitar, banjo, and harmonica with the Mammals.

In 2007, the American Folklife Center honored Seeger and other members of his family with a symposium entitled “How Can I Keep from Singing: A Seeger Family Tribute.” The two-day event was also the occasion for the last concert to feature Pete Seeger and his two half-siblings, Mike and Peggy Seeger, before Mike passed away in 2009. Please visit the symposium site, which contains links to webcasts of the symposium and concert, and to detailed lists of Seeger-related materials in the Archive. You can also read about the Symposium in Folklife Center News.

The concert video, with a time log, is located here.

Pete Seeger performs onstage at the Coolidge Auditorium as part of AFC’s Seeger Symposium, How Can I Keep from Singing? Photo by Robert Corwin, AFC Robert Corwin Collection.

AFC will continue to keep our friends informed about Pete. In the meantime, we extend our sympathies to his many friends, especially his family, including children Daniel, Mika, and Tinya, and grandchildren Tao, Cassie, Kitama Cahill-Jackson, Moraya, Penny, and Isabelle.

Pete Seeger always believed in the power of folksongs to change the world. In the era of increasing military technology, he became less convinced that the banjo would remain mightier than the sword. Still, he refused to lose all hope. In 2005, he was featured on NPR, where he said, “There’s no hope, but I may be wrong.”

On the day after his passing, none of Pete’s lyrics seem more appropriate than these, which he adapted from the Bible’s book of Ecclesiastes:

To Everything (Turn, Turn, Turn)

There is a season (Turn, Turn, Turn)

And a time to every purpose under Heaven

A time to be born, a time to die

A time to plant, a time to reap

A time to kill, a time to heal

A time to laugh, a time to weep

At the American Folklife Center, throughout the Library of Congress, and across America, it’s our time to weep.

January 27, 2014

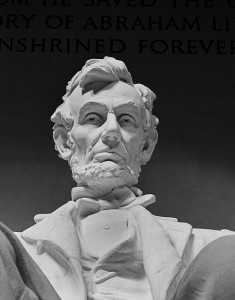

Pic of the Week: Put a Stamp On It

Close-up view of the statue of Abraham Lincoln, sculpted by Daniel Chester French, at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith

Distinguished architectural photographer Carol M. Highsmith began donating her work to the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress in 1992. She has photographed landmark buildings and architecture in Washington, D.C. — including the Library of Congress and many monuments — and throughout the United States. Starting in 2002, Highsmith provided scans or photographs she shot digitally with new donations to allow rapid online access throughout the world.

Last month, the United States POst Office announced a new stamp for 2014 using one of Highsmith’s images in the Library’s collection. The stamp features a black-and-white photograph of the statue of President Abraham Lincoln that is housed in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“In designing the stamp, art director Derry Noyes chose to work with a photograph of a sculpted portrait of Lincoln rather than a more traditional illustration or painting. Carol M. Highsmith’s photograph of this iconic Lincoln statue offered a fresh take,” said the USPO’s blog.

A Feb. 12, 2014, release date has been issued for the Lincoln stamp. You can see more images from the Highsmith Collection here.

January 24, 2014

Preserving the Grammys, and More

(The following is a guest post written by Gene DeAnna, head of the Recorded Sound Section at the Library of Congress Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation.)

Library of Congress Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation, located in Culpeper, Va.

With this year’s Grammy Awards event coming this weekend, it seems a good time to talk about recorded sound preservation. While you may not be on the edge of your seat about whether Daft Punk will win Album of The Year over Taylor Swift, you might be interested in the preservation of recordings made by past Grammy nominees. For example, in 1958 – the first year of the awards ceremony – “The Music From Peter Gunn,” by Henry Mancini, won Best Album. That record was named to the Library of Congress’ 2010 National Recording Registry, and we expect to acquire the original master tapes soon as a gift from the Mancini family. Those tapes will serve as the source recordings for Recorded Sound Section audio engineers at the Library’s Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation to create archival-quality digital preservation files, which in turn will be stored and sustained in the campus’ multi-petabyte digital archive.

That scenario for Mancini’s landmark soundtrack album is as good as it gets in audio preservation. Unfortunately, it isn’t the norm. At the Packard Campus, the Library holds one of the largest and most comprehensive audio collections in the world. Formats range from brown wax cylinders recorded in the 1890s, before mass-production molding methods were invented, to digital files arriving on hard drives. In all, that’s more than 3 million recordings – and all in need of some kind of preservation treatment.

In fact, it may surprise you that some digital formats are more at risk of loss than the 120-year-old cylinders. Some early digital formats were proprietary, requiring a specific manufacturer’s machine to record and play them back. It took only a few years for most of these technologies to become obsolete, and now, 20 years later, finding operational decks to play them is very difficult. So, though the recordings themselves may survive in good physical condition, they are unplayable. Technological obsolescence is one of the major obstacles to preserving audio.

Another challenge is sheer volume. Recordings are time-based media, and they must be played to be preserved, one at a time. Well, not always one at a time. Two of our transfer rooms in the Recorded Sound Section’s audio lab are designed for high-throughput digitization. Audiocassettes and some tape-reel formats can be digitized using simultaneous, multi-channel playback. In simpler terms, by running multiple tape players at the same time through a digital audio workstation, we can drastically increase our productivity. In this process, the engineers can’t listen to everything – only parts of each tape are sampled. Problems could be missed, as the process isn’t perfect. It is in fact a compromise made in the face of overwhelming numbers of recordings that will otherwise physically degrade before they can be digitized. For the 150,000 cassettes in the collections of the Library, it is the only viable approach to save them for future listeners.

Physical degradation is the primary threat to magnetic-tape recording formats and lacquer discs (a widely used professional recording technology developed in the early 1930s, used for recording radio broadcasts, field recordings and studio sessions). Some good news is that when properly stored, even these formats seem to stabilize considerably, and the vaults at the Packard Campus are state-of-the-art. But the clock is ticking even for materials kept in ideal storage conditions. And the scary truth is that there are millions of magnetic tapes, many unique, one-of-a-kind recordings, being stored in basements, garages and attics everywhere. On a recent visit to New Orleans I saw one of the most remarkable collections of sports interviews anywhere – rare recordings of hundreds of sports figures, being stored in a garage. That these tapes made it through Hurricane Katrina was a miracle, but how many more Louisiana summers can they survive?

The challenges are complex and daunting. But great progress has been made. Thanks to David Woodley Packard and the Packard Humanities Institute, we now have the Packard Campus facility. Anyone can listen to what we’ve preserved in the Library’s Recorded Sound Research Center in Washington, D.C. And, speaking of the Grammys, the Library was bestowed an honorary Grammy Award last year for its work over the past decade in preserving historic audio recordings.

We also have one of the best free streaming audio websites ever, the National Jukebox.

And finally, we have a “plan.” For more information about the challenges and solutions to preserving our miraculous, world-changing recorded sound legacy, check out the Library’s National Recording Preservation Plan, published in December of 2012. You can download a free PDF here.

January 17, 2014

Inquiring Minds: Animating the Library’s Collections

More than 25 years ago, retired music executive Joe Smith accomplished a Herculean feat – he got more than 200 celebrated singers, musicians and industry icons to talk about their lives, music, experiences and contemporaries. In 2012, Smith donated this treasure trove of unedited sound recordings to the Library of Congress.

In an effort to bring these interviews to life for the public, multimedia nonprofit Blank on Blank is producing, in collaboration with PBS Digital Studios, an animated series featuring excerpts from the Joe Smith collection, made available through PBS and as podcasts. In addition to recordings from the Joe Smith collection, the web series also features recorded interviews from journalists who have written for Rolling Stone, WIRED, SPIN and Esquire, among others.

Currently featured from the Library are interviews with Barry White, Jerry Garcia and Ray Charles.

David Gerlach

The Library caught up with David Gerlach, Blank on Blank founder and executive producer, to talk about the animated series and working with and using the Library’s collections.

Tell us about your web series, Blank on Blank. What inspired you to create an animated series based on journalist interviews? And, why use old journalist interviews as the source material?

Prior to launching Blank on Blank, I was a television producer at ABC News on Good Morning America. In the mid-2000s, I was a writer for Newsweek and also wrote for publications like Time Out and the New York Post. I recorded the interviews I gathered to write my stories, and I always wondered why no one ever got to hear some of these conversations. Other print journalists I knew would talk about the interviews they did over the years, and the remarkable stories and anecdotes they got on tape that no one ever got to hear. Maybe a few lines ended up in a story, but that was it. Yet these interviews stuck with writers. This is their art. Journalists drag these cassettes – and hard drives filled with digital interview files – as they move from apartment to apartment. I knew there was this untapped archive of amazing interviews that was just waiting to be heard. An American interview archive from some of the country’s greatest storytellers: journalists. We first launched a podcast and series for public and satellite radio curated from these interviews. And I always knew we could use this audio to create new kinds of video content like our animated interviews series with PBS Digital Studios.

Several of your episodes feature interviews from the Library of Congress’ Joe Smith collection. What interested you about these interviews? And why use this particular collection?

This collection captures the stories of American cultural icons. Joe had engaging, casual conversations where you get to hear who these musicians are. But, for the most part, most people never get to hear these tapes unless they know where to find them online. I knew there was an audience in America and around the world that would engage with this unheard slice of American history.

Tell us about your research in using the collection. How do you choose which soundbites and musicians to feature?

We look for stories on life, living and the American experience – the things binding people together that will be fresh and insightful today and years from now. We seek out reflections and asides that you may not expect to hear from a legendary musician whose music you know. It’s about showing what is behind the name and the face.

What are the challenges and benefits of presenting these historical interviews through animation?

The occasional challenge can be sound quality. Oftentimes these historical recordings were made using cassette recorders. For the most part, tape hiss and crackling from analog recordings provides an intimacy, this fly-on-the-wall quality to what people get to hear. There is a beauty in the rawness of these interviews.

Barry White interview

But sometimes too much distortion can be a challenge for the viewer. Thankfully we work with a great team of audio restoration experts who are wizards at cleaning up even the roughest of cassette recordings. Plus, by combining a well-known voice with the animation of Patrick Smith, we hope to provide the viewer with images and ideas that complement what is forming in the mind, as the tape rolls.

Why do you think it’s important to present and offer these historical interviews? What are you hoping to achieve by bringing them to the public in such a way?

I like to say: the future of journalism is remixing the archives. The Internet and cloud technology has made it possible to dust off and distribute so much remarkable content. But it’s also important to go beyond simply offering a huge archive for people to discover. There is so much content out there, and so much to choose from that great stories go unheard. We like to dive into these rich archives and present the interesting nuggets that someone may not know was there.

Why do you think it’s valuable for the Library to preserve such historical collections, and what do you think the public should know about the Library’s mission to preserve this cultural heritage?

The Library of Congress is one of the most vibrant institutions in the country. These collections tell the American story and, in many ways, help explain where we are and where we are going as a nation. Blank on Blank is honored to collaborate with the Library of Congress to help people realize this history that’s being preserved.

Jerry Garcia interview

What’s next for Blank on Blank and using the Library’s Joe Smith collection, or in fact any other of our sound recording collections?

We have an episode upcoming with legendary jazz musician Stan Getz, and now we are busy going through a new crop of interviews from Joe’s collection. This includes his conversations with the likes of John Mellencamp, B.B. King and Pat Benatar. In addition, we are interested in uncovering lost interviews with legendary athletes, artists and thought leaders that are part of the Library of Congress. There is so much to uncover and re-imagine.

And, in closing, any final thoughts on your project and your work with the Library’s collections in producing part of it?

Last winter I had the chance to visit the Library of Congress and the Recorded Sound Reference Center. What a day it was to put on headphones and hear all these amazing interviews. It was like discovering a lost treasure – thanks to the help of the great staff who know these archives inside and out. I knew we could help bring these interviews to life.

January 15, 2014

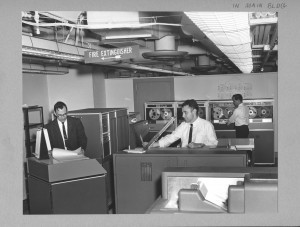

A Half Century of Library Computing

(The following is a guest post from Audrey Fischer, editor of the Library of Congress Magazine.)

Fifty years ago, the Library installed its first computer and began charting a course to bibliographic control and global shared access.

From left to right: George R. Perreault, head of the Data Processing Offiice, standing at the computer storage unit; Ernest Acosta Jr., digital computer programmer, working at the card reader unit; and Joseph B. Murphy, digital computer programmer, inserting a new tape in one of the tape units. Jan. 20, 1964.

On Jan. 15, 1964, the first components of a small-scale computer system were delivered to the Library of Congress and installed in the Library’s newly established Data Processing Office.

Provided for in the Legislative Branch Appropriation Act of 1964 (P.L. 88-248), the IBM 1401 was intended for use in payroll, budget control, card distribution billing, accounting for book and periodical purchases and to produce various statistical and management reports.

A week later, the Library announced the results of a multiyear study on the feasibility of automating its bibliographic functions. Sponsored by a $100,000 grant from the Council on Library Resources Inc., the 88-page report titled “Automation and the Library of Congress” concluded that automation in bibliographic processing, catalog searching and document retrieval was technically and economically feasible. But developmental work would be required for equipment—not yet in existence—and the conversion of bibliographic information to machine-readable format. The report also recommended that the Library of Congress, because of its central role in the nation’s library system, take the lead in the automation venture. Many of the report’s recommendations were implemented in the coming decades, while others, such as a plan for an integrated library system, would wait until the turn of the century.

Throughout the remainder of the 1960s, attempts were made for contractual development of a highly specialized bibliographic information system. The Library ultimately established its own in-house automated systems office (known today as the Information Technology Services Office) for system development. Over the past five decades, the Library has developed more than 250 enterprise systems and applications for use by Congress, and the library, legal and copyright communities, to name a few.

By the early 1970s, the machine-readable cataloging standard known as MARC became the national and international standard for creating records that can be used by computers and shared among libraries. The standard was developed at the Library of Congress by data processing pioneer Henriette Avram, working with various library associations and scientific standards groups.

MARC and the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules (AACR) in their various iterations served the library community for nearly 50 years to describe and organize library collections. Released in 2010, RDA: Resource Description & Access, a new set of instructions suitable for use in a linked data environment, has succeeded AACR2. The following year, the Library of Congress launched the Bibliographic Framework Initiative to address the future bibliographic infrastructure needed to share data, both on the web and in the broader networked world. A major focus of the initiative is to continue the tradition of a robust data exchange that has supported resource-sharing and cataloging cost-savings in recent decades while addressing the needs of 21st-century libraries and information storehouses across the globe.

The Library’s foray into the digital era began in the mid-1980s with several pilot projects to digitize selected items from the Library’s print and non-print collections. Building on the success of the CD-ROM-based American Memory pilot project, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington vowed to make 5 million items accessible electronically to the nation by the year 2000, the Library’s bicentennial year. This goal was realized and the bolstered by the advent of the World Wide Web in the intervening years. The Library’s website debuted in 1993. Today, the Library provides free global access to approximately 40 million online primary-source files.

The Library’s current information technology (IT) infrastructure includes five data centers in four building locations. These facilities support more than 650 physical servers, 400 virtual servers, 250 enterprise systems and applications, 7.1 petabytes of disk storage and 15.0 petabytes of backup and archive data on tape. The Library’s IT infrastructure also includes a wide-area network, a metropolitan-area network and local-area networks that comprise 350 network devices. The Library’s Information Technology Services Office also supports more than 8,600 voice connections, 14,700 network connections and 5,300 workstations.

MORE INFORMATION

January 14, 2014

A Spoonful of Serendipity

(The following is a guest post from Mike Mashon, head of the Moving Image Section in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.)

The Library of Congress’s collection of television programs is broad and deep, consistently revealing some rather unexpected finds. A recent case in point: in the course of selecting two-inch Quadruplex tapes for preservation by the Packard Campus for Audio Visual Preservation video lab, I recently came across a title inventoried as, simply, “P.L. Travers.” Now, I like the Disney version of “Mary Poppins” just fine, but all I really knew about P.L. Travers was that she thought so little of the adaptation that she refused all entreaties for further film treatments of Poppins stories. Suitably intrigued, I asked for it to be preserved.

A few days later, I downloaded the digital file from our archive server and was quite surprised to see an opening slate with the words “Library of Congress” on it. It turns out that the program was one in a series of late-Sixties joint productions between the Library and public television station WETA in Washington, D.C., each featuring well known authors and poets like John Updike, Rod Serling and James Dickey discussing their work. With the kind and generous permission of WETA, we will share more of these shows in future blog posts.

The program with P.L. Travers is quite different from the others in that she takes questions from a group of children – who prove to be adept interviewers – even if one gets the sense that some of their inquiries might have been provided to them beforehand. Everyone studiously avoids any mention of the film – released two years before this November 1966 recording – but it remains a fascinating and rare television appearance by Mary Poppins’ creator. If you know anything about this production (especially if you are one of the children!), we’d love to hear from you.

And in a welcome instance of serendipity, between the time of the tape’s preservation and this online presentation, “Mary Poppins” was named to the 2013 National Film Registry by Librarian of Congress James Billington. While one hesitates to hazard what P.L. Travers would think of the coincidence, it does seem practically perfect in every way.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/pl_tra...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumStandard'

}

January 13, 2014

Write Your Family History – And Send it to the Library of Congress!

(The following is a guest post by James Sweany, head of Local History and Genealogy in the Humanities and Social Sciences Division.)

Blank family record. 1888. Prints and Photographs Division.

The best way to preserve your family history is to write it down. By publishing your family history, you are able to capture and preserve the stories, pictures and genealogical data, making it available for other family members and future generations. A history of your family will make a wonderful gift for your relatives, and you may find that your family becomes inspired to help you seek out additional family branches.

As my colleague Anne Toohey wrote in her blog post on Christmas Day, by writing your family history, you are taking the known names, dates and places of your ancestors, and providing a historical context in a story-like form. This way, your ancestors become much more than names on a pedigree chart. They become people who lived during an earlier time, who had experiences through which you and others can get to know them through your narrative. If you include photographs and images of vital records or other significant events, the text will come alive and will be much more interesting for the reader.

The key to making your family history useful to others is the organization. A table of contents and an index of names and places used in your history will take additional time, but these added details will be very useful to future researchers consulting your history. Also, it is very important to document your research. By compiling and publishing a family history, you are inviting others to continue your research. Cite your records and document your sources. With documentation, others can build upon on the work you have done, and your history is more credible. There are various style manuals that can assist you with citation styles for footnotes, endnotes and bibliographies. If you decide to distribute your family history outside of your immediate family, be sure not to include personal information about people who are still living in order to protect their privacy.

The Library of Congress can help you find books about writing and publishing your family history. For example, how-to guidebooks that will help you organize your family history and resources on how to find a publisher can be identified in the Library of Congress Online Catalog. We invite you to seek guidance from our reference librarians through Ask a Librarian. For assistance with resources that may be found in your local area, consult your public or nearby university library to search other library catalogs. Local genealogical societies and historical societies are also great resources for additional guidance.

When you write your family history, you may only be doing so for your relatives. However, we also invite you to consider sending a copy to the Library of Congress. Compiled genealogies and U.S. local histories are very important to the international research clientele who frequent the institution. The Library seeks to collect all published and self-published works available on these important topics. Through generations of such gifts, the Library has assembled the leading book collection of genealogy and local history information in the world.

And who knows, perhaps not yet discovered relatives will be led back to your family line through your sharing of your family story!

January 10, 2014

Pic of the Week: Kate DiCamillo, National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette. Author Kate DiCamillo was sworn in today as the newest Library of Congress National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.)

Kate DiCamillo signs a book for a young fan during today’s ceremony. / Shealah Craighead

The inner voice of Kate DiCamillo belongs to a 10-year-old girl from a small Florida town who learned to navigate the world through books she checked out at the local library.

“That connection to the 10-year-old kid, I’ve come to believe through the years, is more immediate for me than other people,” said DiCamillo, the best-selling author of “Because of Winn-Dixie” and “The Tale of Despereaux.” “Maybe that’s why I write for kids. That 10-year-old is front and center all the time for me.”

That innate ability to empathize with young readers makes DiCamillo a natural for her new role: On Jan. 2, she was named by Librarian of Congress James H. Billington the national ambassador for young people’s literature.

“Kate DiCamillo is not only one of our finest writers for young people but also an outstanding advocate for the importance of reading,” Billington said. “The Library of Congress is pleased to welcome Kate as a worthy successor to our three previous national ambassadors.”

The ambassadorship was established in 2008 by the Library’s Center for the Book, the Children’s Book Council and Every Child a Reader to raise awareness of the importance of literature to children’s literacy. The ambassador serves a two-year term, appearing at events around the country and encouraging young people to make reading a central part of their lives.The young Kate DiCamillo certainly did.

DiCamillo was raised in Clermont, a small town in central Florida, in a home filled with books. Kate’s mother read to her, bought her books and sent her for more to the tiny, wood-framed Cooper Memorial Public Library – a place that held unique importance in her life.

“It was this old house filled with books, and the librarians knew me and gave me special privileges: I could check out more than four books at a time,” DiCamillo said by phone from her Minneapolis home last week. “Being seen by those librarians as somebody who was special and who loved to read – that shaped me. It was also how I made sense of the world, through books.”

She read, she said, “without discretion”: Beverly Cleary, “Little House on the Prairie,” “The Twenty-One Balloons” and, over and over, a biography of George Washington Carver – anything she could get her hands on.

“I was just wide-ranging. Whatever it was, I would read it,” she said. “Loved, loved, loved books.”

At the University of Florida, a professor noticed her facility with words and urged her to consider graduate school. But she passed, deciding instead to become a writer – or, at least, pose as one.

“I just got a black turtleneck and started wearing that, because that’s what writers wore,” she said. “I started talking about how I was going to be a writer. And, no lie, that’s basically how I spent the next 10 years.”

She worked at Disney World, Circus World, a campground – but never wrote a thing.

“The whole time I’m saying, ‘I’m a writer, I’m a writer, I’m a writer,’ ” she said. “It wasn’t till I turned 30 that I figured out I was actually going to have to write something.”

DiCamillo began writing short stories, moved to Minneapolis and took a job in a book warehouse as a “picker,” pulling volumes off shelves to fill orders. She had never considered writing for children, but fate landed her on the warehouse’s third floor – filled entirely with children’s books. She read them and got inspired.

“I thought, I want to try to do this,” she said.

Through her work at the book distributor, DiCamillo connected with editors at Candlewick Press and eventually submitted a draft of a novel about a lonely girl who adopts a mischievous dog she encounters in a grocery store. The finished novel, “Because of Winn-Dixie,” was published in 2000 and earned a Newbery Honor as one of the year’s best children’s books. Her follow-up, “The Tiger Rising,” was named a finalist for the 2001 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature. In 2003, “The Tale of Despereaux” won the Newbery Medal as the year’s best American book for children.

She since has produced three more novels, two picture books and two series of chapter books, and both “Winn-Dixie” and “Despereaux” were made into feature-length films – a wave of success that still leaves DiCamillo wondering what happened.

“I’m sitting here with my mouth hanging open,” said DiCamillo, who began writing with modest expectations: She hoped just to earn enough to go part-time in her other job.

That’s why, in part, she wants to serve as ambassador.

“There is a part of me that still can’t believe I got published,” she said. “So much has been given to me by this community. I want to try to give back.”

DiCamillo chose as her platform “Stories Connect Us” – the act of reading brings people together and the power of literature helps people better understand each other.

“It’s more than reading together, but partly that: Teachers to students, grandparents to grandchildren, parents to their kids, kids to their parents, communities reading together,” she said. “That is a way to connect.

“And when you’re sitting alone in your room [reading], you’re connecting with other people by imagining other lives.”

The 10-year-old DiCamillo connected to the world that way. Ambassador DiCamillo hopes to help others do the same.

“I feel really lucky to get to do this,” she said, “to tell stories for a living, and to be the ambassador and to go out and talk about the power of stories.”

More information about the national ambassador for young people’s literature is available at read.gov/cfb/ambassador/.

January 9, 2014

InRetrospect: December Blogging Edition

Blogs around the Library of Congress decked the halls with a variety of posts in December. Here are a few selections to unwrap.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Podcast: Song Travels | Michael Feinstein Interviews Rosanne Cash

Singer and musician Michael Feinstein interviews Rosanne Cash and John Leventhal about Cash’s new album “The River and the Thread.”

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

Featured Advertisement: Buy Useful Presents!

Holiday shopping ads aren’t a thing of the past.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

New Year’s Greetings from the Law Librarian of Congress

Law Librarian David Mao ushers in the new year with a look back at the Law Library’s successes in 2013.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

11 Great Digital Preservation Photos of 2013

Photos document digital preservation.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Helping Students Visualize the Process of Change With Historic Images

Stephen Wesson highlights library resources that help document historical change in our nation.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Caught Our Eyes: Santa Gets Credentials

This photograph documents Santa receiving the “all clear” to fly the skies on Christmas Eve.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress

Poetry in the School Library

Teacher in Residence Rebecca Newland discusses fostering a love of poetry in students.

Folklife Today

Auld Acquaintance for the New Year: Burns’ “Auld Lang Syne”

Stephen Winick presents the history of the traditional New Year’s tune.

Library in the News: December 2013 Edition

Every year, the Library of Congress announces the addition of 25 films to the National Film Registry, and every year, media outlets far and wide run stories on the initiative. According to a Google search on the story, more than 230 news articles highlighted the selections for 2013.

“To me, this honor goes on the same shelf as the Oscar or the Palme d’Or,” filmmaker Michael Moore told The Washington Post on the selection of his film “Roger & Me” to the registry.

Moore also took to the Huffington Post to issue a thank you to the Library for the inclusion of his film.

“The nanny Mary Poppins and the nasty Vincent Vega are now ensured a place where they can spend their golden years growing old together, using whatever they wish to help the medicine go down,” wrote the New York Times blog, The Carpetbagger, on the inclusion of “Pulp Fiction” and “Mary Poppins” to the registry.

“At the time of their release it would have been hard to imagine Tarantino’s breakout, Moore’s anti-car industry doc or a B-movie such as ‘Forbidden’ ever being recognized by Congress. Time brings a unique perspective,” wrote Gregory Ellwood for .

“The Library of Congress National Film Registry is an elite and rather special club. It places a premium on timelessness and historical import, and it always makes room for a few films you’ve never heard of,” wrote Chris Vogner for The Dallas Morning News.

National outlets running stories included USA Today, LA Times, CBS News, PBS Newshour, Time, Variety, Entertainment Weekly, Hollywood Reporter, Vanity Fair, UPI, Associated Press.

Regional outlets in Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Maine, Delaware, Michigan, Missouri, Indiana, South Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, Colorado and California, among others, also highlighted the registry.

International media, including AFP, malaymailonline.com (Malaysia), Irish Independent, BBC News and the Times of India featured stories as well.

Speaking of films, the Library recently released a report that conclusively determined that 70 percent of the nation’s silent feature films have been lost forever and only 14 percent exist in their original 35 mm format.

“The report underscores some of the difficulties faced by archivists dedicated to preserving the world’s cinematic heritage, from full length features to educational filmstrips. Some of the films may remain intact in archives where harried film technicians have not had time to identify, much less restore the work. Others, though, are likely gone forever, lost to an early Hollywood culture that saw no value in maintaining movies they couldn’t sell tickets to anymore” wrote Library Journal’s Ian Chant.

“Our film heritage doesn’t begin with “Casablanca,” “The Wizard of Oz” or “Gone with the Wind.” Silent films are a full-blown form of entertainment, and some are an art form,” said Audrey Kupferberg with WAMC Northeast Public Radio.

And in other preservation news, the Library found and recently restored work – a painting of the Madonna – by Mexican artist Martin Ramirez.

“It is a charming and energetic picture showing an angelic figure, with an androgynous face and a radiant crown, standing on a luminous blue globe,” wrote Philip Kennicott for The Washington Post. “Surrounding her, and rendered in a different perspective, are two canyons filled with what seem to be automobiles, driving from a landscape of green trees toward the bottom of the vertical landscape, perhaps south, to Mexico.”

“Ramírez was making drawings, almost all of them lost, in the 1930s and ’40s, but not until the early 1950s did the larger world take notice. That makes the Madonna at the Library of Congress one of the earliest of his surviving works from the period when the outside world was just beginning to take notice,” he added.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers