Library of Congress's Blog, page 163

March 12, 2014

(Motion) Pic of the Week: An Award-Winning Memoir

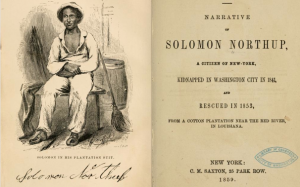

“12 Years a Slave” won the Oscar for best picture at this year’s Academy Awards. The film, based on the 1853 memoir of Solomon Northrup, made history as the first movie from a black director (Steve McQueen) to win the film industry’s highest honor in 86 years of the awards ceremony.

“12 Years a Slave” won the Oscar for best picture at this year’s Academy Awards. The film, based on the 1853 memoir of Solomon Northrup, made history as the first movie from a black director (Steve McQueen) to win the film industry’s highest honor in 86 years of the awards ceremony.

In his memoir, Northrup, a free black man born in New York, recounts to editor David Wilson his kidnapping in Washington, D.C. and subsequent sale into slavery. He was kept in bondage for 12 years in Louisiana before securing his release.

The Library of Congress owns two versions: an 1859 edition from the General Collections and an 1853 edition in Rare Book and Special Collections Division. The 1859 version is available from the Library through the Internet Archive. Here you can turn the pages of the book as if you had it personally on hand. The volume has also been digitized in color to give a much more realistic impression of the book than other grayscale versions that are online of other printings.

March 11, 2014

Sports Gold

(The following is a guest post by Matthew Barton, curator of recorded sound in the Library’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.)

Ron Barr with Fox Announcer and former NFL Coach Brian Billick.

Last year, the Library of Congress acquired the first of more than 10,000 radio interviews conducted by Ron Barr, founder and host of radio’s Sports Byline USA. The interviews date from 1988 and feature figures from across the world of sports: athletes, coaches, trainers, managers, owners, writers and others in the areas of baseball, football, basketball, hockey, soccer, tennis, golf, racing, boxing, track and field and numerous other sports. Throughout his career, Barr has sought out not only active competitors but the veterans of earlier sports generations, who have illuminated their eras and achievements for today’s listeners. Interviews such as these enrich the Library’s sports holdings in all media, going back many generations.

Sports coverage has been an ongoing fixture of radio broadcasting since its earliest days, one of the few constants in the ever-changing media world. The Sports Byline interviews form an invaluable archive of the nation’s athletic heritage, and an extensive resource for historians, researchers, fans and sports professionals. Notable interviewees include John Wooden, Reggie White, Mickey Mantle, Elgin Baylor, Hank Aaron, Oscar Robertson, John Elway, Jose Canseco, Charles Barkley, Mike Krzyzewski, Jimmie Johnson, John Mackey, Archie Griffin, Bonnie Blair, Bill Bradley, Willie Mays, Jim Brown, Barry Sanders, John McEnroe, Natalie Coughlin and Meadowlark Lemon. Some are available now online.

In this 1997 interview, the great Elgin Baylor talks about his early days of playground basketball in Washington, D.C. in the 1940s, and why, of all his achievements, he remains proudest of his rebounding.

[media player not shown]

This Friday, Barr is a featured speaker in a wide-ranging roundtable discussion of sports, broadcasting and preservation. Joining him are Brian Billick, football commentator and former Super Bowl-winning coach of the Baltimore Ravens, and Adonal Foyle, a 13-year NBA veteran who, through his charitable work, helps needy children and encourages civic involvement. Gene DeAnna, head of the Library’s Recorded Sound Section, and myself will be on hand to discuss the Library’s continuing commitment to the gathering and preservation of sports media.

The program will also feature highlights of some of Barr’s favorite interviews with various sports figures such as Negro Leagues baseball legend Buck O’Neill and wide receiver Jerry Rice. Also in the mix will be unique broadcast clips from the Library of Congress collection, dating back to the early 1930s. Sports radio broadcasting and sports itself have changed enormously over the generations, and this event is a unique opportunity to experience its past, present and future. Plans to make further Sports Byline interviews available online in the near future will also be discussed during this panel.

Free and open to the public, the program begins at noon in the Mumford Room on the sixth floor of the James Madison Building Memorial Building, 101 Independence Ave., S.E., Washington, D.C.

March 10, 2014

A Grand Hotel on the Cycle of Creativity

(The following is a guest post by the Library’s Director of Communications, Gayle Osterberg.)

I have been reading with enthusiasm recent interviews with the screenwriter/director Wes Anderson about his forthcoming film “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” not only because I am a fan of Mr. Anderson’s work, but because he has been talking about the Library of Congress. Specifically, he’s been talking about how he has recently used the Library.

Ring Street, Budapest, Hungary. ca. 1890-1900. Prints and Photographs Division.

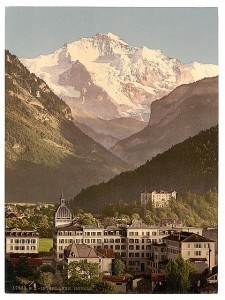

Anderson and his production designer, Adam Stockhausen, reportedly (The New York Times, Dazed) studied the Library’s online photochrom prints collection, which includes almost 6,000 images from the 1890s and 1910s created by photo companies in Zurich and Detroit.

The collection includes stunning landscapes and images of both interiors and exteriors of cathedrals, theaters and, of course, hotels. Anderson recently explained to the New York Times that after searching through the photos, they traveled around Eastern Europe looking at some of the locations – some of which look “very close to the old pictures” – and used the images to assist in recreating the look and feel of a hotel of that time and place.

In addition to making me want to immediately become a production designer (traveling the world – who knew?), the articles also reminded me of what I have come to regard as the “cycle of creativity” that the Library of Congress supports and safeguards through its work.

The Library adds about 12,000 items to its collections on average every business day. Those items are acquired through several means but most predominantly from copyright deposits.

Authors register their works and deposit original copies with the U.S. Copyright Office to support enforcement of their intellectual property rights – an important piece of our nation’s legal framework to encourage authorship.

Interlaken, hotels, Bernese Oberland, Switzerland. ca. 1890-1900. Prints and Photographs Division.

These new works join centuries old manuscripts, photographs, wax cylinders, books and other items in the Library’s 158 million-plus collection and are cared for and preserved using a range of specialized methods developed by the Library’s preservation and conservation teams. (You can read stories about just a few recent examples here.)

And finally, those collections are made available to the public, either on site at the Library’s research facilities or, in the case of the photochrom print collection, online. Practicing creators and scholars can look, study, read, touch, learn, be inspired and create new works that will themselves be registered for copyright and potentially not only entertain and inform audiences today but inspire and inform future generations of researchers and authors.

I wonder if the photographers based in Zurich and Detroit at the turn of the century imagined their images would one day more than 100 years later inspire a filmmaker’s efforts to remake a grand hotel? I wonder whom Anderson’s new film will, in turn, inspire 100 years from now (his screenplay has already been registered with the Copyright Office, natch). We cannot know for sure. But someone a century from now at the Library of Congress will.

March 8, 2014

InRetrospect: February 2014 Blogging Edition

Between winter and the winter olympics, the Library of Congress blogosphere offered up a variety of posts during February. Here is a sampling:

In The Muse: Performing Arts Blog

ASCAP on the Occasion of its 100th Birthday with Jimmy Webb and Paul Williams

The Library celebrates ASCAP.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry & Literature at the Library of Congress

Olympic Promotion Ads Inspire Through Poetry

Poetry features prominently in Olympic ad campaigns.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Curling: Right on the Button

Historical photographs showcase the sport of curling.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Snow, the Law Library of Congress and Congressional Coverage

Law librarians share snow-day recollections.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology & Business

King of Winter Sports

Hockey is highlighted in the Library of Congress collections.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Saving Mementos from Virtual Worlds

Mike Ashenfelder shares preservation tips for the gamers.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Preparing for Spring By Celebrating School Gardens

A lesson on school gardens can chase away winter blues.

Folklife Today

“The Fox”: A Song for Pete and Capitol Hill

Fox sighting inspires folksong reminiscences.

March 7, 2014

Library in the News: February 2014 Edition

News in February brought word of several Library of Congress collection resources. Here are a few headlines.

On January 30, the Library launched an online collection showcasing selected items from the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive, along with elements from other important science-related collections at the Library.

Gizmodo highlighted eight of the most fascinating items from the collection. Included in the list were a home movie of a young pianist Sagan, a rough draft of his novel “Contact” and ideas for a video game version of the novel “as exciting as most violent video games.”

“The Sagan archive gives us a close-up of the celebrity scientist’s frenetic existence and, more important, a documentary record of how Americans thought about science in the second half of the 20th century,” wrote Joel Achenbach for Smithsonian Magazine.

Also running articles were Boing Boing and The Verge.

Launching just a week later was the Library’s “Songs of America” presentation, which explores American history through music.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer featured highlights of the new presentation.

“Just how amazing is this collection? There are 55 items related soley to the song ‘Amazing Grace’ with versions from the likes of Johnny Cash, Elvis, Willie Nelson, The Byrds and Sam Cook.”

Other outlets running stories were CBS, WJLA and the Associated Press.

While this collection isn’t available online yet, the Archive of American Public Broadcasting will be an archive of countless hours footage and audio tape from the mid-20th century through the first decade of the 21st century that contain local, regional, and national history, news, public affairs, civic affairs, religion, education, environmental issues, music, art, literature, filmmaking, dance, and poetry. The digital preservation files the archive creates will be held at the Library of Congress, and the public-facing website launches in 2015.

According to an article in The Atlantic, the Library will preserve the material “for the life of the republic plus 500 years.”

One of the Library’s most popular online collections is its Prints and Photographs Online catalog, which includes more than 1.2 million digitized images from the Prints and Photographs Division. Scholars, researchers, enthusiasts and even celebrities from around the world have access to this resource. Noted film director Wes Anderson was inspired by the Photochrom Prints collection for his new film “The Budapest Hotel.”

“Using the U.S. Library of Congress archive of photochrom images from 1895 to 1910, Anderson pieced together a visual aesthetic that was brought to life by [Adam] Stockhausen and art director Stephan Gessler,” wrote Trey Taylor for Dazed.

The New York Times also wrote a travel and arts feature on the movie and Anderson’s inspiration for the hotel at the center of the film.

Ten Thousand Treasures

The World Digital Library – a website of world cultural treasures offered free of charge in seven languages to anyone on the planet with access to the Internet – has put up its 10,000th offering.

It was part of a package, actually – a group of rare manuscripts from the collections of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, which has been a contributor the WDL since 2010.

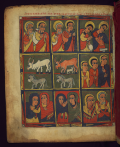

Rare manuscript from the Walters Art Museum, now on World Digital Library

If you’re not careful, you can easily become addicted to the World Digital Library. The wondrous focal point for manuscripts, maps and atlases, books, prints and photographs, films, sound recordings, and other cultural treasures was launched in 2009 with just a few hundred items and has been adding content and bringing new libraries and museums on board ever since. The site was the brainchild of Librarian of Congress James H. Billington, and was made a reality with the cooperation of the Library and UNESCO.

All items on the WDL site are presented in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish. Using a drop-down menu on the homepage – which looks like a huge map of the world – you can choose the language you’d like to use for your explorations, then go browsing within the WDL by a number of selection methods including place, time, topic, type of item or the institution that holds the original.

The Walters contributions include an early 16th-century Gospel manuscript from Ethiopia, written in Amharic and in Geez, the ancient liturgical language of Ethiopia; a manuscript containing a richly illuminated Ottonian Gospel book fragment believed to have been made at the monastery of Corvey in western Germany during the mid-to-late 10th century; and a menologion, or church calendar, in Greek, created in Byzantium circa 1025-1041.

Other items recently added to the World Digital Library include block-print books from China’s Song Dynasty, Islamic manuscripts in Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Turkish, early 20th-century historical documents from the League of Nations, and codices once found in the legendary library of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary.

One of my favorite offerings in the WDL is the full digitized set of books titled “Description of Egypt” that Napoleon ordered created when he invaded that nation; they contain gorgeous, detailed illustration plates showing Egypt’s flora, fauna and amazing antiquities.

Another is this rare gem of Americana.

What treasures have you found in the World Digital Library?

March 6, 2014

Pics of the Week: Celebrating Women’s History

The Library of Congress is an incomparable resource for research into women’s history and studies, which is especially appropriate in March, Women’s History Month. This year’s theme is “Celebrating Women of Character, Courage and Commitment.”

Spanning all time periods, classes, races and occupations, the Library’s women’s history resources are among the finest and most comprehensive anywhere. Contained in nearly every collection are materials of interest reflecting the full range of women’s experiences.

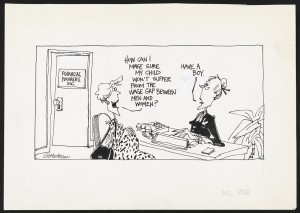

Signe Wilkinson. “How can I make sure my child won’t suffer from the wage gap between men and women?” Drawing with ink, opaque white, blue pencil. 1988.

The Library recently acquired several selections that strengthen the Library’s research holdings in women’s studies, particularly in the Prints and Photographs Division.

An award-winning American political cartoonist, Signe Wilkinson became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1992. Her wry commentary on the wage gap between the sexes was published in Ms. Magazine in November 1988. Wilkinson has addressed equality issues for women and others over many years.

Carolyn Drake. New Kashgar, Kashgar, China. digital photograph. 2011.

American artist Carolyn Drake created vibrant photographs of contemporary people in the ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar, China. The photograph on display comes from her “Two Rivers” series, which features more than 30 photographs showing current Central Asian life along the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers.

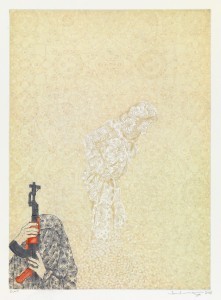

Ambreen Butt. Untitled print from the series “Daughter of the East.” Etching and aquatint. 2008.

Boston-based Pakistani artist Ambreen Butt merges aesthetic elements of Mughal and Persian painting with contemporary subject matter – often relating to the lives of women. Her beautiful work raises many questions about how their roles are changing. The featured print is from a series that shares the title of an autobiography by Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who was assassinated in 2007.

Rupert García. “Frida Kahlo.” Screen print, 1975. (Photo by Shealah Craighead)

Iconic Mexican artist Frida Kahlo has been the subject of many works of art. The Library’s recent acquisition of her portrait was created by leading Chicano artist Rupert García. Working with Library curators, artists from San Francisco’s Mission Gráfica and La Raza studios have placed more than 1,000 prints and posters from the 1970s to 2010 in the Library’s collections.

February 27, 2014

Inquiring Minds: A Study of Mental Health

(The following is a guest post by Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the Library’s John W. Kluge Center.)

Manuella Meyer

Manuella Meyer is the David B. Larson Fellow in Health & Spirituality at the Library’s John W. Kluge Center and assistant professor of history at the University of Richmond. Her research examines the socio-political and medical terrain in which mental illness became a public health construct and its subsequent management in Rio de Janeiro during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Meyer’s project examines narratives of madness and concepts of mental illness articulated by psychiatrists during a time of rapid socio-political and cultural transformation. The study dialogues with historians and social scientists across geographical boundaries about public health, the history of welfare, gender, race discourse, state building, modernity and the socioeconomic organization of post-emancipation societies.

Q: Tell us about your research.

A: I’m working on my book manuscript, currently titled “National Melancholia: Madness, State and Society, 1808-1930.” It’s an examination of politics and medicine primarily seen through the lens of psychiatrists. I am interested in how a given society defines madness at a particular moment and how psychiatrists, in addition to other actors, have attempted to manage it.

Q: How do madness and mental health get defined?

A: The project understands madness as a real illness that affects, and continues to impact, various groups and communities. Nonetheless, it is not transhistorical. Insanity requires analysis not only of the individual mad person but also of the social, political, institutional and professional structures that determine how and why a society treats that person as mad. During a time of rapid socio-political and economic transformation, known in Brazilian history as the Imperial and Old Republic eras, I investigate how race, gender, class and anxieties about modernity undergird ideas about madness and mental health.

Q: Why choose Brazil for this topic?

A: Brazil is popularly understood as a place of great contrasts, a place where high-rise luxury hotels are a few feet away from sprawling favelas, a place where the wealthy and the poor challenge and intimidate one another. During a visit to Rio de Janeiro many years ago, I became fascinated by how the affluent attempted to care for marginalized populations. This interest in the politics of care deepened as references to the “unfortunate” insane that frequently dotted mid-19th century state and medical documents in the archive sparked an academic interest in welfare and social policy. I became intrigued by how mental illness became a critical matter for both state and civil societies in addition to how both medical and religious groups sought to claim professional expertise over it.

Q: How do notions of power play into this?

A: Issues of power are at the center of this project. During the time period under investigation, psychiatrists warned of crisis as they surveyed Rio de Janeiro. Fluent in the argots of criminology, eugenics and degeneration theory (the notion that national decline was due to the supposed inferiority of Brazil’s racial composition), psychiatrists championed science and expertise to address not only mental illness but also a range of issues such as poverty, crime and delinquency.

These approaches played a fundamental role in changing the professional position of psychiatry from a peripheral discipline of marginal scientific status to a prominent field able to provide the state with a framework to address both medical and socio-political concerns.

Q: Are there strict definitions of madness, and do they evolve through the period that you’re researching?

A: Absolutely. Definitions and understandings of madness evolve over time. There is not one particular definition. For example, late 19th century Brazilian psychiatrists perceived that conversing with spirits (i.e. the ability to communicate with the dead) was in and of itself a form of mental illness. In contrast, this practice was a critical component of the respective cosmologies of spiritist mediums, candomblé (a syncretic Afro-Brazilian religion) healers and their followers.

Q: What does the Library have in its collection that is critical to this research?

A: The Library has been fundamental to my research. For example, I’ve been mining the newspaper serial collection for the 19th and early 20th century in order to explore how psychiatrists wrote accounts about the flagship asylum and prophylactic measures to ward off mental illness, in addition to other topics. Also, the Library of Congress has the proceedings of late 19th and early 20th century medical congresses, where Brazilian psychiatrists debated with experts from countries such as the United States, Belgium and France. I’ve been looking at these items to see what topics were seminal to these practitioners.

Q: What sort of implications does this research have for how we think about madness and mental health?

A: A very complex question. In terms of implications for today, it has bearings on how we care for others. This research asks us to contemplate the following: What exactly does it mean to care for society’s marginalized populations? What is the role of the state, as well as the role of competing practitioners and care providers in regards to welfare? Who “deserves” social assistance? Who does not? The project urges a consideration of how we make sense of marginality and how we devise solutions to address it.

Meyer lectures on the history of madness and mental health in Brazil on Thursday, March 6 at noon in LJ 113. Applications are currently being accepted to be the next Larson Fellow at the Kluge Center.

February 25, 2014

Conservation Corner: Rare Drawing by Martin Ramirez Conserved and Unveiled

(The following is a guest post by Holly Krueger, head of the Paper Conservation Section of the Library of Congress Preservation Directorate.)

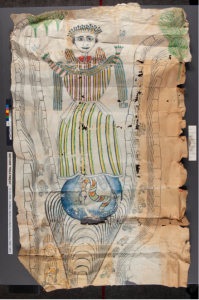

Figure one: Before treatment (front)

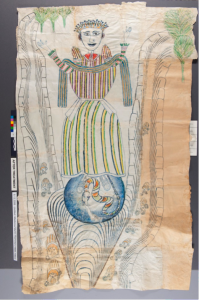

Last December, the Library of Congress unveiled a remarkable drawing by the “outsider artist,” Martin Ramirez. The drawing depicts a Madonna figure standing on a blue globe surrounded by canyons filled with anthropomorphic cars. The story of its discovery and rescue is an interesting one.

Ramirez emigrated from Mexico in 1925 to find work to support his family. By 1931, he was institutionalized in California where he remained for the rest of his life. Diagnosed as catatonic, manic-depressive and finally schizophrenic, Ramirez never saw his family again and died in 1963. While institutionalized, he began to create beautiful, enigmatic drawings with found materials. He masticated bread, oatmeal or potatoes to paste together sheets of “junk mail” and drew with various materials, including homemade inks and matchstick heads. The work was so compelling that it drew the attention and support of his doctors – who supplied him with materials – and notable artists like Wayne Thiebaud. The work of Ramirez is highly sought after and has been the focus of several major exhibitions and published monographs.

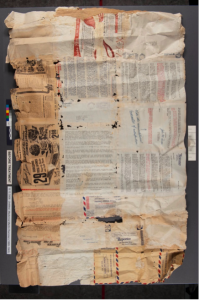

Figure Two: Before treatment (back)

During routine processing of the Library’s Ray and Charles Eames collections, curator Tracy Barton found a crumpled up object at the bottom of a document box. Once she removed and gently unfolded it, she thought she was looking at a child’s drawing (Figure 1), something the Eames’ were known to collect. Upon turning it over and seeing the patchwork of pasted together junk mail, with a bit of detective work, she knew she had something much more. (Figure 2). Barton had uncovered a previously unknown drawing by Ramirez, a Madonna figure that is especially rare in his oeuvre. Because of the materials used, this piece is considered by experts to be one of his earlier works.

The drawing was transferred to the Library’s conservation experts to receive much needed treatment to make it stable and presentable enough to handle and display. Senior Paper Conservator Susan Peckham began the process of resurrecting the heavily damaged piece with a thorough examination and consultation with Prints and Photograph curator Katherine Blood. The drawing was greatly distorted with many tears and creases, having been stored in the bottom of a document box for many years. The homemade adhesive created and used by Ramirez had proven irresistible to insects while in the Eames warehouse in California, resulting in many losses throughout. (Figure 3).

Figure Three: Detail of insect and rodent damage

The surface plane was gradually restored through a variety of moistening and flattening techniques. The process was especially complicated by the number of different types of paper pasted together to form the support, as well as the extreme solubility of some of the media used. (Figure 4) In order to mend the tears, Japanese paper strips were adhered with wheat starch paste, transparent enough to provide stability while maintaining legibility of the back of the drawing. Paper toned to blend in with the surrounding support filled in any losses. To restore visual integrity to the drawing, Peckham then painted in those losses by drawing the lost design onto a separate piece of thin tissue cut out to the exact dimensions of the loss and then adhered that to the drawing so that no non-original media was added directly to the paper itself (Figure 5) .

Figure Four: Susan Peckham testing solubility

Compensation of the loss of design areas was an aspect of the treatment that required numerous consultations with Blood. The aim of color compensation was to enable the viewer to read the drawing without being distracted by losses, while maintaining the story of the drawing’s journey from Ramirez to the Eames warehouse in California to, ultimately, the Library of Congress. Peckham achieved a perfect balance. (Figures 6 and 7)

Figure Five: Inlay inserted into loss

Concurrent to the conservation process, Peckham worked with the Preservation Research and Testing Division (PRTD) to analyze some of the materials in the drawing. XRF and Fadometer readings identified some of the pigments to the extent that responsible exhibition conditions could be determined, anticipating a high demand for viewing in the near future. PRTD was also able to support the theory that bread was used as the basic adhesive in construction of the support. Through the analysis provided by PRTD and Peckham’s research into and identification of likely media used, details of Ramirez’s methods and materials are better understood, enhancing the preservation state of this remarkable drawing.

After treatment and analysis were completed, the drawing was framed and unveiled during a ceremony that included members of the Ramirez family. It remains on view through March 15 in the “Exploring the Early Americas” exhibition on the second floor of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building.

You can read more about the Ramirez drawing in this blog post.

Figure Six and Seven: After treatment (front and back)

February 19, 2014

George Washington’s Philadelphia Household, 1793-1794

(The following is a guest post by Julie Miller, specialist in early American history in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division.)

Think of all the things your household buys and uses. Now think of George Washington. He was the commander of the Continental Army, first president of the United States and the father of our country, but he was not so different. Even though your expenses might include electricity, digital downloads, dry cleaning and gas for your car and his were candles, silver shoe buckles, clothing for his slaves and oats for his horses, the principle is more or less the same: the things we buy say a lot about who we are and the world we live in.

George Washington’s household expense book

This month, as part of a temporary display on the first three United States presidents on view on the first floor of the Thomas Jefferson building of the Library of Congress, you can see a small paperbound book containing Washington’s household expenses for 1793 and 1794. Maintained by a secretary (Martha Washington’s nephew, Bartholomew Dandridge), records the purchases of George Washington’s household in Philadelphia during a part of his second term as president. This volume is just one of many financial records that Washington kept throughout his life and that are part of the George Washington papers in the Library’s Manuscript Division.

For most of his presidency, Washington lived in a rented house in Philadelphia that served as both home and office. His household there consisted of his wife, Martha Washington; her two grandchildren, Eleanor (Nelly) Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis; secretaries; and a household staff consisting of both servants and slaves. What did this household buy? To keep the house running, they bought ice in January to store in the ice house and use later on, wood and candles, the services of chimney sweeps, brooms for the stable, oats for the horses, and “grease for the horses feet.”

In March 1794, Washington paid for “mending an umbrella to be kept at the door.” This is something we can all relate to – who doesn’t keep an umbrella by the door? But Washington had his umbrella mended – something that likely most of us don’t do. Washington’s umbrella was made by hand, possibly in Philadelphia, and it would have been expensive, worth mending.

The Washingtons bought themselves things that defined their status as a well-to-do 18th-century family: gloves for servant Patrick Kennedy to wear while placing “table ornaments;” hair powder for the president; feathers and ribbons for Martha; French and painting lessons, a harpsichord and a “pair of gold ear drops” for Eleanor Custis; a Latin book and fishing tackle for her brother; theater and a museum tickets; tailoring and hairdressing; butter, sugar and wine; picture frames; and books and newspapers.

Both George and Martha Washington gave alms to the poor when they encountered them. The president also responded to direct appeals. One came from “two distressed French women,” refugees from the Haitian revolution. Another was from Peregrine Fitzhugh, a Revolutionary War veteran, down on his luck, who raised money for himself with a lottery, offering tracts of land as prizes.

What about the servants and slaves who kept the household going? There are periodic glimpses in these pages of steward Samuel Fraunces receiving cash “to purchase sundries for the household.” Fraunces, who historians largely agree was a free black man from the West Indies, was the innkeeper in whose New York tavern George Washington said goodbye to his troops at the end of the Revolutionary War. He returned to innkeeping after this stint (his second) as Washington’s steward. The other servants appear when they are paid their wages, and at a few other times as with Patrick Kennedy and his gloves.

Overseeing the servants was housekeeper Ann Emerson, a widow with three children, who earned $33.33 per quarter. The slaves, who of course were not paid, appear in this book when the Washingtons bought clothes for them: “stockings for Austin,” “mending or altering boot for John whose foot was sore,” and money given by Mrs. Washington directly to Molly and Oney to buy shoes and stockings for themselves. These people are identifiable as slaves because they are listed here without surnames, something 18th-century slave owners commonly did. They are also mentioned elsewhere in Washington’s papers. Compared to the many details that survive about the Washingtons, these lives are documented by tiny fragments of information.

One of the most revealing things in this little book is the record of the Washingtons’ reading. Martha, who read for both pleasure and enlightenment, bought most of the books. She bought a play, poetry, religious works, geography books, two books about the French Revolution (the worst part of which, the “Terror,” was then in progress), and two books about the yellow fever epidemic that ravaged Philadelphia in 1793. She also bought “Thoughts on the Education of Daughters” (1787) by Mary Wollstonecraft, well-known author of the 1792 “A Vindication of the Rights of Women.” All of these books are briefly described, so it is hard to tell which edition Martha bought, but editions of most of them were published in Philadelphia in the 1790s. Mrs. Washington may have seen them in a Philadelphia shop or heard about them at her own dinner table.

Similarly evocative is a March 7, 1794, notation of “sundry books bought by the president.” Maybe that day George Washington grabbed the old umbrella by the door, went out for a walk and wandered into a bookshop. It hadn’t occurred to anybody yet that a president couldn’t go out without a motorcade, even one pulled by horses.

The information in this book has the effect of drawing us close to the Washington household and at the same time distancing us from it. In some cases their needs and ours are the same: when it rains, we reach for an umbrella, just like George Washington did. But just as we are rooted in the specifics of our own times and places, so were the Washingtons. In their time, the United States was a political experiment and Philadelphia was its capital, the French and Haitian revolutions were in progress, and people lived in terror of yellow fever. Today very few of us rely on a houseful of workers to take care of our needs, people who live in cities no longer keep horses, we benefit from modern medical care and disease prevention, and, most significant of all, we no longer are slaves or own slaves. These are the important things that this little book has to tell us.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers