Library of Congress's Blog, page 159

June 5, 2014

InRetrospect: May 2014 Blogging Edition

Inside Adams: Science, Technology and Business

Oh, Oology!

Caliology and oology are the study of bird nests and eggs, respectively.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Best Buddies, or Just Goethe Friends?

Tchaikovsky and Brahms share a birthday, among other things.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

I Could Not Accept Your Challenge to Duel. It’s Not You, It’s Me

In Kentucky, lawyers are not allowed to duel.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Save the Date: Exploring Calendar and Scheduling Formats

Kate Murray takes a look at software such as iCalendar.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Visiting Washington D.C.? Enrich Your Trip With Primary Sources

Primary sources can help you explore the history and the architecture behind D.C.’s historic buildings.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints and Photos

The Library needs your help in identifying historic structures.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress

Is Your State Laureate-less? You Can Help Change That

Peter Armenti offers tips on how to establish a poet laureate for your state.

Folklife Today

From Cornwall to the Ozarks: More May Celebrations

Stephen Winick looks at May celebrations across the globe.

Now See Hear!

Awopbopaloomop Alopbamboom!

Little Richard talks about his early days.

NLS Music Notes

Quincy Jones and Who?

Professional musician Justin Kauflin is also an NLS patron.

June 4, 2014

Library in the News: May 2014 Edition

As May came to an end, so did the second and final term of Natasha Trethewey as U.S. Poet Laureate. She gave her final lecture at the Library of Congress on May 14.

“At the Library of Congress on Wednesday night, Trethewey began, as she often does, with her personal history and then moved into a rich exploration of America’s racial heritage,” wrote Washington Post reporter Ron Charles.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Rosalind Bentley also wrote about Trethewey’s final lecture and term. “As she brings her two terms as the nation’s top poet to a close this Wednesday, Natasha Trethewey chose the words of a homeless Seattle teen she met last year, to, in a fashion, sum up what has been her mission as the nation’s poet laureate.

“She said that being able to write about the ugly things that she’d experienced in life, through poetry, she was able to turn them around and make them beautiful.”

While one term was ending, another was beginning. In May it was announced that David M. Rubenstein, co-founder and co-CEO of the Carlyle Group, will serve as chairman of the private-sector advisory group to the Library, the James Madison Council, beginning October 2014.

Making the announcement were outlets including the Associated Press, The Washington Post and CBS local news.

The Library plays host to many esteemed individuals, who also study and give lectures at the institution. John Bew, Henry A. Kissinger Chair in Foreign Policy and International Relations, has been at the Library since last October researching the notion of realpolitik, where policies are formulated based more on practical geostrategic and national interests rather than lofty ideals.

Bew spoke with Washington Diplomat reporter Larry Luxnor.

“While at the Kluge Center, Bew is tapping the extensive collection of presidential papers and other research material at the Library of Congress to write his history of realpolitik,” Luxnor wrote. “He [Bew] describes the library’s manuscripts as among ‘the best resources in the world’ and says he’s used the Kluge Center just about every day since his arrival in the United States.”

On a more reflective note, the spring issue of the Wilson Quarterly featured stories from U.S. veterans on life and war in Afghanistan pulled from the collections of the Veterans History Project. Highlighted are poignant stories from husbands, fathers, journalists and more.

The Library continues to make news as a must-see spot while visiting Washington, D.C. New York Times reporter Jennifer Steinhauer spent 36 hours on Capitol Hill, where she visited the Library.

“One of the city’s greatest troves of stories, artwork, history and architecture, the Library of Congress, which began as Thomas Jefferson’s personal library, is often skipped over, although there is much to see here,” she wrote.

Speaking of Thomas Jefferson, NPR reported on the Library’s ongoing efforts to track down and acquire books that once belonged to Jefferson. The goal is to finish filling in the gaps to Jefferson’s library, which he donated to the institution after the British burned the Capitol in 1814. In 1851, another fire destroyed a large part of the collection.

“16 years ago, the Library of Congress sought to restore Jefferson’s original collection and find exact copies of all the books that burned in the 1851 fire,” said reporter Laura Sullivan. “Staffers kept the project a secret so as not to drive up prices. They were looking for about 4,000 books. And they started where anyone else would go to look to for really old, rare books – their own bookshelves. The Library of Congress’s catalog turned up 2,000 of them. [Mark] Dimunation picked up almost 2,000 more at auction houses, public libraries and book dealers, but the last 250 he can’t find anywhere. Either no one’s got a copy, or it’s a book nobody alive now has ever heard of.

“The collection is now displayed with markers. A green ribbon means the book belonged to Jefferson – it was his book. A yellow ribbon means it’s an exact copy – same edition, same printing press. A black box with a title means that the book is still missing. Jefferson believed books were not to be collected – they were to be used, read, absorbed by as many people as possible. It’s a philosophy this library has adhered to for 200 years.”

May 30, 2014

Stay Up With a Good Book, Too –

The 2014 National Book Festival poster by Bob Staake

The author lineup for the 2014 Library of Congress National Book Festival is growing all the time, building excitement for the free event being held Saturday, August 30 from 10 a.m. – 10 p.m. at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center.

Yes, that’s right, a 12-hour day in a new venue, with all the features you know and love by day and a bunch of fascinating new offerings by night – a first in the festival’s 14-year run.

Recent additions to the speakers’ list include science writer Michio Kaku; novelists Mona Simpson, Elizabeth McCracken, Anne Hillerman and Sara Sue Hoklotubbe; graphic novelist Raina Telgemeier; poet Albert Rios; kids’ authors Jack Gantos, Francesco Marciulano, and Judith Viorst; and chef/authors Cathal Armstrong, Sheilah Kaufman, Amy Riolo and Laura and Peter Zeranski.

Following the day’s talks, with Q&A, by more than 100 authors for readers of all ages – and book-signings by those authors—the festival will offer special events between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. including a poetry slam, a panel discussion/screening titled “Great Books to Great Movies,” and a “super-session” for fans of the graphic-novel genre.

The festival’s new location also facilitates an expanded selection of genre pavilions. In addition to the longtime pavilions History & Biography, Fiction & Mystery, Poetry & Prose, Children’s, Contemporary Life, Teens and Special Programs, this year’s festival also will offer new pavilions focused on Science, the Culinary Arts, and for young readers, Picture Books.

For more information, go to the festival website. While you’re there, you can download this year’s festival poster by artist Bob Staake. (Turn up the sound if you click Bob’s link!)

May 27, 2014

The Library in History: Library Analyst Helped Launch NASA

(The following is a story written by Cory V. Langley, a communications specialist in the Congressional Research Service, that is featured in the May – June 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

Amid fear and anxiety following the launch of Sputnik 1, a Library analyst assisted Congress in creating the agency that landed Americans on the moon.

The American public was shocked, and its leaders were concerned for national security when, on Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1—the first artificial Earth satellite.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, center, meets with NASA’s first administrator and deputy administrator, Thomas Keith Glennan, right, and Hugh Dryden, left, 1958. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Lyndon B. Johnson, then a U.S. senator and chairman of the Senate Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee, called on a national defense analyst in the Legislative Reference Service (forerunner of the Congressional Research Service) to assist Congress in determining how to respond.

Library analyst Eilene Galloway had recently authored a report for Congress titled “Guided Missiles in Foreign Countries” and had focused on the issue of military manpower and the organization of the Department of Defense. Johnson asked Galloway to serve as the subcommittee’s staff consultant for a series of hearings on satellite and missile programs, at which Members of Congress heard the testimony of preparedness experts, scientists and engineers. Galloway drafted questions and analyzed testimony.

“While our first reaction was that we faced a military problem of technology inferiority, the testimony from scientists and engineers convinced us that outer space had been opened as a new environment and that it could be used worldwide for peaceful uses of benefit to all humankind, for communications, navigation, meteorology and other purposes,” Galloway wrote in 2007.

“Use of space was not confined to military activities,” she wrote. “It was remarkable that this possibility became evident so soon after Sputnik, and its significance cannot be understated. The problem became one of maintaining peace, rather than preparing the United States to meet the threat of using outer space for war. Fear of war changed to hope for peace.”

With those ideas in mind, Galloway advised Sen. Johnson and House Speaker John McCormack in crafting the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Thus, Galloway entered the frontier of space policy. Her seminal contributions to the act included her recommendations that NASA be formed as an administration, so that it could coordinate with government agencies under centralized guidance, and that NASA be encouraged to act internationally.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the act into law on July 29, 1958—just nine months after the launch of Sputnik. Eleven years later, Apollo 11 delivered Americans Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the moon.

EILENE GALLOWAY

Eilene Galloway. Manuscript Division.

Born in Kansas City, Mo., in 1906, Eilene Marie Slack graduated from Swarthmore College with a degree in political science. She married George Galloway, a prominent expert on the workings of Congress, who also worked for the Congressional Research Service. Galloway retired from the Library in 1975, but as one of the world’s experts on the subject, she continued to work on space law and policy issues the rest of her life.

She served on NASA advisory committees, participated in international colloquia and published many articles. She was a founding member of the International Institute of Space Law. She received the NASA Public Service Award and Gold Medal (1984) and was the first recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from Women in Aerospace (1987). She was a fellow of the American Astronautical Society (1996) and the first woman elected Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (2006). The annual international Galloway Symposium on Critical Issues in Space Law is named for her.

Galloway died in Washington, D.C., in 2009—just days shy of her 103rd birthday.

May 21, 2014

CRS at 100: Informing the Legislative Debate Since 1914

(The following is an article compiled by Cory V. Langley, a communications specialist in the Congressional Research Service, that is featured in the May – June 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

An all-staff meeting is held in the Senate Reading Room (now the Jefferson Congressional Reading Room). 1948. Prints and Photographs Division.

The centennial of the Congressional Research Service is a time to look back on its history and ahead to serving a 21st-century Congress.

When the Legislative Reference Service (LRS) was established in the Library of Congress in 1914, the small staff provided what its name conveyed—reference information to assist Members of Congress in their legislative work. Over 100 years, LRS evolved into today’s Congressional Research Service (CRS), a staff of 600 that exclusively provides Congress with nonpartisan policy analysis.

CRS is known for its reports, but what makes CRS is its people—analysts, attorneys, information professionals, and management and infrastructure support staff. These staff members carry out services in support of the modern mission: to provide objective, authoritative and confidential legislative research and analysis, thereby contributing to an informed national legislature.

“The success of CRS in fulfilling its statutory mission is a direct result of diligent professional staff, entrusted with the critical task of researching issues and analyzing information and data for elected officials,” said CRS Director Mary B. Mazanec.

Tailored, Personalized Service To Congress

CRS staff members respond to specific congressional questions in a variety of ways: in person, by telephone and in confidential memoranda. CRS staff members also assist Members of Congress and their staffs in preparing for hearings and provide expert testimony.

For example, the House Armed Services Committee last year invited Catherine Dale, a specialist in international security, to testify about the transition in Afghanistan—the formal handover of security responsibility from coalition to Afghan forces. “My role was to frame key oversight issues before other witnesses presented their proposed prescriptions,” said Dale. “Afterward, members and staff from both sides of the aisle sought me out for assistance.”

Library staff members Judy Graves and Pamela Craig conduct a webinar on Congress.gov. 2013. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

Reports on Major Policy Issues

CRS analysts, legislative attorneys and information professionals prepare reports on legislative issues. CRS’s analyses are available to all of Congress on an exclusive CRS website, where nearly 10,000 reports are searchable and organized by issue area.

“I issued a report within 24 hours of a tragic wildfire incident,” said Kelsi Bracmort, a specialist in agricultural conservation and natural-resources policy. “The short report succinctly described one facet of wildfire management, directed the reader to other related reports, and, most importantly, immediately let Congress know that there was a CRS policy specialist available to discuss this matter in depth.”

Assistance Throughoutthe Legislative Process

Throughout all stages of the legislative process, CRS works with committees, members and congressional staff to identify and clarify policy problems, assess the implications of proposed policy alternatives and provide timely responses to meet immediate and long-term needs.

“Congress relies on CRS’s legal expertise in many stages of the legislative process,” said Julia Taylor, who heads the American Law Consulting Section. “Before a bill is introduced, we’re often asked to research legal definitions for terms or conduct a survey of state laws to see how an issue has been handled across the country. As the bill moves through Congress, we research issues relating to the potential impact of the new law. Congressional staff may ask about the nature of recent litigation. They may also ask for research related to floor statements the member would like to make when the bill comes up for debate.”

Francis R. Valeo, chief of the Foreign Affairs Section, consults with Mary Shepard, analyst in international organization. 1951. Prints and Photographs Division.

Process and Procedures

CRS assists lawmakers and their staffs in understanding the formal and informal rules, practices and precedents of the House and Senate and how they might be employed in the legislative process.

“I’m part of a group that supports Congress on legislative rules and procedures,” said Valerie Heitshusen, analyst on Congress and the legislative process. “We consult on legislative strategy, analyze current and historical procedural practices, and explain implications of potential procedural options. Examples include helping senators assess proposed changes in the practice of filibusters, serving as a procedural resource in committee markups, and identifying the range of opportunities Members of Congress may have to offer amendments to pending legislation.”

The Future

In its first century, CRS has acquired a store of knowledge and experience that Congress can rely on. At the present time, when there is an overwhelming amount of information readily available, it is even more essential that Members of Congress have access to issue experts in CRS who can assist them by gathering, analyzing and summarizing the most pertinent information.

“We work in an environment in which many entities are competing for members’ time and attention,” said Director Mazanec, who is involving the entire staff in developing formats and delivery methods for CRS products and services that are most helpful to the 21st-century Congress.

“CRS will stay true to its values and align with Congress’s needs. We want Congress to turn to CRS first when it is in need of research and analysis to support its deliberations and legislative decisions.”

“CRS will continue to provide Congress with the independent scholarship required as it embarks upon its second century of distinguished service,” said Librarian of Congress James H. Billington.

Current CRS Director Mary Mazanec (back row, center) leads the Research Policy Council. 2013. Photo by Karl Weaver, Congressional Research Service.

CRS at 100: A Timeline

July 1914

On July 16, President Woodrow Wilson approves the fiscal 1915 appropriations bill, which includes $25,000 for legislative reference. Two days later, Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam establishes the Legislative Reference Service (LRS) by administrative order.

1930s

LRS responds to a congressional directive to publish a digest of public bills and takes over the production of the “Constitution Annotated,” a compilation of constitutional case law, which the Library began publishing in 1913.

Early 1940s

World War II leads to rapid growth in LRS, with every senator and a majority of U.S representatives turning to LRS for reference assistance.

1946

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 calls for an immediate increase in the size and scope of LRS to meet the information needs of Congress in the post-war era.

1950s

LRS assists Congress on issues such as the Cold War, civil rights, social security, and science and technology. The press calls LRS “Congress’s right arm.”

1970s

The Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 transforms and renames LRS. The newly restructured Congressional Research Service (CRS) becomes Congress’s own think tank for objective, nonpartisan policy analysis.

1980

CRS establishes the La Follette Reading Room in the Library’s new James Madison Memorial Building to honor Senators Robert M. La Follette Sr. and his son, Robert, for their support for a congressional research department in the Library of Congress.

1981

CRS holds its first Federal Law Update briefings on current legal topics of interest to Congress, which continue to the present day with new programs and workshops on policy issues.

1995

CRS launches CRS.gov, a website for Congress. At Congress’s request, the Library develops an online public legislative information-tracking system known as THOMAS. CRS develops the Legislative Information System (LIS) to serve the legislative branch.

2012

The Library of Congress, in collaboration with the U.S. Senate, House of Representatives and the Government Printing Office, launches Congress.gov, an improved website that will replace the legacy legislative tracking systems for Congress and the public.

2013

The Library of Congress, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration and the Government Printing Office launch the “Constitution Annotated,” a new app and web publication that make the printed version of constitutional case law accessible for free on a computer or mobile device.

2014

CRS celebrates its centennial. CRS continues to enhance its staff capabilities, diversify its research products and streamline its website.

May 19, 2014

Library Launches Portal For Civil Rights History Project

(The following is a story written by my colleague, Mark Hartsell, editor of The Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter.)

Simeon Wright / Civil Rights History Project

Simeon Wright still recalls the terror of the night they came and took his cousin away.

“I woke up and saw these two white men standing at the foot of my bed,” Wright said. “One had a gun, flashlight. He ordered me to lay back down and go to sleep. He made Emmett get up and dress and marched him out to the truck.”

Wright witnessed one of the most notorious incidents of the civil-rights era: the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American from Chicago who was murdered during a visit to relatives in Mississippi in 1955. Wright drove into town with Emmett, watched him come out of the store, and heard him whistle at a passing white woman. And he was at home, asleep, when the woman’s husband and other men came to the house, took Emmett away and killed him.

“They drove off, and we never saw Emmett alive again,” Wright said. “But in that house that night, I never went back to sleep.”

Wright’s story is one of 55 interviews placed online by the Library of Congress as part of the Civil Rights History Project, a congressionally mandated initiative to collect, preserve and make accessible personal accounts of the civil-rights movement.

A Mandate from Congress

The Civil Rights History Project Act, passed in 2009, directed the Library and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) to conduct a survey of existing oral-history collections related to the movement and to record new interviews with people who participated.

The American Folklife Center (AFC), which manages the project at the Library, today officially made videos and transcripts of those interviews and a database of oral-history collections around the country available online.

“The project is unique in its capacity to expand our collective awareness and understanding of one of the most fundamentally important social, political and cultural movements, not just for this country but the world over,” said Guha Shankar, project director for the AFC. “At the same time, the public can immediately connect to the intimate, unfiltered stories of people in the freedom struggle through the interviews online and also find similar stories that exist in libraries in their own backyard via the searchable database.”

Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Bradley / Prints and Photographs Division

The database, the first of its kind, makes available to researchers information about civil rights oral-history collections at public libraries, museums, universities and historical societies in 49 states and the District of Columbia. Library contractors conducting the survey of repositories nationwide discovered a surprisingly large number of collections.

“We thought they’d find maybe 150 collections and instead they found over 1,500,” said Kate Stewart, who helps manage the project for the AFC. “It’s a big and quite comprehensive database.”

The Library’s partner, the NMAAHC, chooses the interview subjects, and the interviews – now more than 100 of them – are conducted by the University of North Carolina’s Southern Oral History Program. The Library catalogs the interviews, makes the video and transcripts available, and provides copies to the Smithsonian for inclusion in the NMAAHC, scheduled to open on the National Mall in 2015.

A Movement of Everyday People

The project focuses not on prominent figures of the movement, but on foot soldiers – the young men and women who sang, marched and protested, who witnessed historic events, who watched great leaders work up close.

“There’s always been such a focus on the history of certain people, like Martin Luther King or Rosa Parks,” Stewart said. “These interviews tell different stories, things that you wouldn’t have thought about before.”

Jamila Jones recalls riding public buses in Montgomery, Ala., and Parks offering her Kool-Aid and cookies at an NAACP youth group meeting. She also recalled a tense moment during a police raid on a community meeting. The group began singing “We Shall Not be Moved,” and she spontaneously added the line “we are not afraid.”

Mildred Bond Roxborough, a longtime secretary at the NAACP, recalls working alongside many of the movement’s great leaders – and the impressions they made not as historic figures but as real people who could be funny, difficult, compassionate, tough.

“I never heard so many cuss words in my life, which was colorful,” Roxborough said of Thurgood Marshall, who later became the Supreme Court’s first African-American justice. “He was a wonderful raconteur. He had a tremendous sense of humor.”

Sisters Joyce (left) and Dorie Ladner / Civil Rights History Project

Sisters Doris and Joyce Ladner grew up together, became activists together, helped organize the March on Washington together and, in interviews conducted for the project five decades later, still finish each other’s sentences. Joyce recalled the excitement and glamour of the March on Washington in 1963: seeing Josephine Baker and Marlon Brando, meeting Lena Horne – and the singer who crashed at their apartment in the days before the march and kept everyone awake.

“Bobby Dylan [was] sitting on the sofa strumming his guitar, and I wanted to go to sleep,” she said. “And he would sit there until midnight, and I just couldn’t wait until he would go to sleep.”

They also recalled the murder of activist Medgar Evers in 1963 – they’d known him as girls in Mississippi – and the horror of the trial of the man charged with the killing, Byron De La Beckwith. Each day, they said, De La Beckwith would enter the courtroom to a standing ovation from some in attendance – applause he received with a bow.

“Like some famous rock star,” Joyce said.

‘Powerful, Very Powerful’

Freeman Hrabowski, now president of the University of Maryland Baltimore County, participated in the “Children’s Crusade” march of young people in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963. Hrabowski, then 12, was leading his group, when they were confronted by a policeman.

“He was so angry, he spat on me,” Hrabowski said. “I’ll never forget it. He spat in my face. Picked me up and threw me. They came and got the kids, and they just threw us into the paddy wagon.”

Later, King led parents to the jail where the students were held and spoke to the crowds outside.

“We were looking through the bars, and they were singing the songs,” Hrabowski said. “And he spoke. He said, ‘What you do this day will have an impact on children yet unborn.’ I didn’t even understand it, but I knew it was powerful, powerful, very powerful.”

The AFC eventually will place all the interviews online, and excerpts will be included in the Library’s exhibition, which opens in June, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“The civil-rights movement is such a fundamental part of American history,” Stewart said. “You can read about it in textbooks, but oral history is such a moving way to learn. It really engages people in a way I don’t think the average textbook does.

“A lot of these people are talking about things they did as teenagers. What motivated them to do that? They were really risking their lives or putting themselves in danger to do this.”

The database of oral-history collections related to the civil-rights movement is available here.

May 15, 2014

Library Welcomes New Blog, NLS Music Notes

The Library adds another blog into its blogosphere today. Welcome NLS Music Notes.

The blog is designed to share information about the services of the Music Section of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped and its special format music collection: in braille, large print and audio. The blog will highlight the collection — which is the largest music braille collection in the world and very much an international one — new acquisitions and the patrons who use the collections and NLS services.

Take a look at today’s inaugural post.

The Power of One: Roy Wilkins and the Civil Rights Movement

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library’s staff newsletter, The Gazette, for the May-June 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. The Library exhibition, “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Long Struggle for Freedom,” opens June 19 in the Thomas Jefferson Building.)

Rev. Martin Luther King, seated next to NAACP Director Roy Wilkins. 1964. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

Civil Rights activist Roy Wilkins devoted his life to achieving equal rights under the law for the nation’s African Americans.

The legacy of slavery, Roy Wilkins once wrote, divided African Americans into two camps: victims of bondage who suffered passively, hoping for a better day, and rebels who heaped coals of fire on everything that smacked of inequality. Wilkins belonged among the rebels.

“I have spent my life stoking the fire and shoveling on the coal,” he wrote in his autobiography, “Standing Fast.”

Wilkins, the grandson of Mississippi slaves, devoted more than 50 years of that life to advancing the cause of civil rights, speaking for freedom and marching for justice. He led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) during the civil rights movement’s most momentous era—the years of freedom rides and bus boycotts, the March on Washington and the march from Selma, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the murder of Medgar Evers and the police dogs and fire hoses of Birmingham.

Wilkins’ family hailed from Mississippi, but his father was forced to flee to St. Louis after an altercation with a white man—one step, Wilkins recalled, ahead of a lynch rope.

Wilkins was born in St. Louis in 1901, followed closely by a sister and brother. His mother died when he was 5, and relatives contemplated sending the two older children back to Mississippi and the baby to Aunt Elizabeth and Uncle Sam in St. Paul, Minn.

Roy Wilkins meets with President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House to discuss strategies for securing passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Prints and Photographs Division.

Sam wouldn’t hear of it. “I won’t break up a family,” he telegraphed. “Bring all three.” Those nine words changed Wilkins’ life.

In St. Paul, Wilkins lived in an integrated, working-class neighborhood of Swedish, Norwegian, German and Irish immigrants and attended integrated schools—experiences that later allowed him to view whites as civil-rights allies and to reject militant activism.

Sam emphasized hard work and education. No one can steal an education from a man, he’d say. He also taught Wilkins to keep faith in the goodness of others, that the world was not a wholly hostile place.

“Everything I am or hope to be I owe to him,” Wilkins wrote.

After graduating from the University of Minnesota, Wilkins eventually edited an influential African-American newspaper in Kansas City, where he first encountered widespread segregation. Wilkins’ work drew the attention of NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White, and in 1931 he moved to New York to serve as White’s chief assistant and, later, editor of The Crisis magazine. With the NAACP, Wilkins fearlessly took his cause to the streets. He led many protests, helped organize the historic 1963 March on Washington and participated in marches in Selma, Ala., and Jackson, Miss.

Wilkins mostly sought to force change within the system, through legislation and the courts. He led the legal efforts that culminated with the historic 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education that overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine in public schools—a decision, he said, that gave him his greatest satisfaction.

In 1955, Wilkins took over as the NAACP’s director and implemented a strategy designed to get all three branches of the federal government actively working to advance civil rights.

“We wanted Congress and the White House to come out of hiding and line up alongside the Supreme Court on segregation,” he wrote.

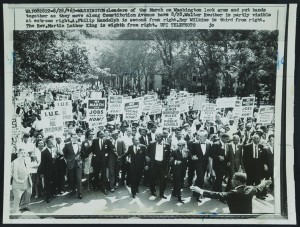

Leaders of the March on Washington lock arms as they walk down Constitution Avenue, Aug. 28, 1963, with Martin Luther King Jr., far left, and Roy Wilkins, second from right. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph

Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

The legal cases, protests and marches helped produce historic legislation in the 1960s, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964—a measure Wilkins called a “Magna Carta for the race, a splendid monument for the cause of human rights.”

Wilkins retired from the NAACP in 1977 and died in 1981, leaving behind an America radically changed for the better.

“The only master race is the human race,” he once said, “and we are all, by the grace of God, members of it.”

REMEMBERING THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act and the struggle for racial equality, the Library of Congress will present a new exhibition. “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom” will open on June 19, 2014, and remain on view through June 20, 2015. The exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from Newman’s Own Foundation and with additional support from HISTORY.

Drawn from the Library’s collections, the exhibition will include 200 items, featuring correspondence and documents from civil rights leaders and organizations, images captured by photojournalists and professional photographers, newspapers, drawings, posters and in-depth profiles of key figures in the long process of attaining civil rights.

Audiovisual stations will feature oral-history interviews with participants in the Civil Rights Movement and television clips that brought the struggle for equality into living rooms across the country and around the world. Visitors also will hear songs from the Civil Rights Movement that motivated change, inspired hope and unified people from all walks of life. In addition, HISTORY has produced two videos about the legislation and its impact that will be shown in the exhibition.

Make sure to check back next Thursday for another spotlight on other items from “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Long Struggle for Freedom,” as the Library of Congress blog leads up to the June 19 exhibition opening.

Download the May-June 2014 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

May 13, 2014

Pics of the Week: Behind the Music

Ann and Nancy Wilson. Photo by Amanda Reynolds

Last week, the Library hosted the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) Foundation for its annual “We Write the Songs” concert, featuring the songwriters performing and telling the stories behind their own music. Carly Simon, Randy Newman and Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart joined others in performing some of their most popular tunes.

“We used to tell our mom and dad that we were going to the library when we actually were rocking out,” Ann Wilson said before performing Heart’s “Dog and Butterfly” and “Crazy on You.” “Now, we’re actually at the Library, rocking out. They would be so thrilled.”

A sentiment surely shared by many of the performers taking the historic Coolidge Auditorium stage.

“Hasn’t this been the best concert you’ve ever been to?” Simon asked. “This astonishes me.”

[image error]Carly Simon at the sixth annual “We Write the Songs” concert. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

The Library is home to the ASCAP collection, which includes music manuscripts, printed music, lyrics (both published and unpublished), scrapbooks, correspondence and other personal, business, legal and financial documents, scrapbooks, and film, video and sound recordings.

Established in 1914, ASCAP is the first United States Performing Rights Organization (PRO), representing the world’s largest repertory of more than 8.5 million copyrighted musical works of every style and genre from more than 350,000 songwriter, composer and music-publisher members.

May 12, 2014

Inquiring Minds: Commemorating the Federal Writers’ Project

David A. Taylor

David A. Taylor is the author of “Soul of a People: The WPA Writers’ Project Uncovers Depression America” and writer and co-producer of the Smithsonian documentary, “Soul of a People: Writing America’s Story.” On Thursday, he joins others at the Library for an event marking the 75th anniversary of “ These Are Our Lives ,” a collection of life histories produced during the New Deal era by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Read more about it here.

Your book, “Soul of a People” (2009), is about the WPA Federal Writers’ Project. What about the New Deal program inspired and interested you to write the book?

I came to the Writers’ Project by chance, from using the series of travel guidebooks the WPA writers produced – what we now call the WPA guides. A friend lent me the “WPA Guide to New Orleans,” and I found in it a fresh and authentic portrait of the city and its people: gritty and vivid and unlike any guidebook I’d read before. The editor, Lyle Saxon, had been a journalist and a novelist before, and I became curious: How had that book and the others in the series come about? Eventually I wrote an article for Smithsonian magazine using the WPA Guide to Nebraska as a test of its durability. It held up surprisingly well, too. So I became intrigued by this sudden nationwide agency of writers.

For that article I got to speak with several of the Project’s survivors including Studs Terkel, who championed oral history in many forms – from his radio interviews to his books, which he called “oral histories.” He was generous with his time and memories. In following those leads and reading their papers, I found the story of their intersecting lives at that time of crisis fascinating. The stories and conversations led to the book and a documentary film, also titled “Soul of a People,” produced by Spark Media and funded by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and state humanities councils.

Studs pointed me to Ann Banks, whose book “First-Person America” contains selections from many of the rich life histories gathered by the WPA writers. She was really the first to rediscover that collection in the Library of Congress in the 1970s. We’re thrilled that she will join us for the May 15 event.

Tell us about your experience using the Library’s WPA collections for your research. What did you learn that helped you develop your book?

I researched my first book, a cultural history of ginseng, at the Library and had learned so much from the reference librarians in the Main Reading Room. When I started this project, the research took me into more parts of the Library, especially the Manuscript Division (which holds much of the editorial correspondence of the project and personal collections of several WPA alumni), the American Folklife Center (which has the life histories and recordings gathered by the Folklore Division of the Writers’ Project) and Prints and Photographs (which has all the wonderful photographs from the Farm Security Administration).

Each collection gave a part of the puzzle. For example, I could find the life histories that Ralph Ellison conducted, now in the American Folklife Center, and then go to Ellison’s personal collection in the Manuscript Division, a rich trove that was cataloged not long before. Zora Neale Hurston’s plays are also there. Then I visited Prints and Photographs and saw Ellison’s photos from his early years and his friendship with other WPA writers, including John Cheever. I learned how these individuals approached their work and friendships and how they sometimes reflected on influences later.

What collection items did you find most illuminating? Any life histories stand out in particular?

The life history interviews were fascinating to read through. May Swenson’s interviews in the Bronx, for example, were a wonderful surprise. As a young project employee, this great poet captured people in glimpsed observations and quirks of character. Really, it was fascinating to find the many stories of everyday people documented with the intent of capturing their words.

For entering the experience of a young person going from poverty to the thrill of finding their voice as a storyteller, it’s hard to top paging through Ralph Ellison’s letters. As a young man, he poured himself out in correspondence. His exchanges with Richard Wright are hard to top for a window into brilliance, creativity and youth. One of the life history interviews he did was with an older man on a park bench in Colonial Park in Harlem – a park where Ellison himself had spent his first nights when he arrived in the city, homeless. It’s a rich interview where Ellison taps a flood of honest outrage, with a poignant backstory.

For heartbreak, I’m struck by the interview with James Griffin, a 21-year-old whose account was recorded during a Florida sound recording tour arranged by Zora Neale Hurston. I included Griffin’s story in “Soul of a People.” In a turpentine camp, he’s asked by his WPA interviewers – including a young Stetson Kennedy – the story behind his song, “Worked All Summer Long.” Griffin explains he was jailed for 90 days at hard labor in the Dixie County Prison Camp to repay $50 to a lumber company. The song came to him while he was in jail.

“I started singing it and thought it would be my theme song,” he said.

He and the other inmates would take it up in the evening after the day’s labor.

“We’d be singing,” he said. “It helps.”

Then he sings the song for the recording. The song includes a prayer from the singer’s mother, asking that someone look down and see him, wherever he may be. His recording, from a hot day in August 1939, still lives here.

“These Are Our Lives,” written 75 years ago, featured selections from the Federal Writers’ Project. Tell us a bit about the book. How significant was it at the time, and what about it endures today?

That book was a departure, in that it showed a new way to portray history. It was a collection of life histories gathered by WPA interviewers in the South, as part of a nation-wide effort led by Benjamin Botkin, the project’s folklore director. In 1939, traditional historians still considered history to be an expert’s distillation of key documents and leaders, and folklorists were focused on tall tales and legends – not living history from people’s mouths. The New York Times reviewed “These Are Our Lives” twice when it came out, calling it “history of a new and peculiarly honest kind” and “an eloquent and important record.” One review hoped it might be the first of a series. Although that was originally Botkin’s plan, it didn’t happen. Budget cuts would soon shutter the whole Writers’ Project.

I think the book’s most enduring quality is its intimacy with people’s lives and their voices, across race and economic background. At their best, these stories evoke a scene in Wim Wenders’ film, “Wings of Desire,” where two angels dressed in overcoats wander through a subway car, listening to the unspoken fears and dreams of the people there. In some ways, the WPA interviewers were doing that. They were often the first ones ever to ask everyday people for their stories, and often neither interviewer nor interviewee knew what would come out.

The event on May 15 will highlight this sense of intimate history. In addition to StoryCorps, there will be actors bringing to life two selections from “These Are Our Lives.” The actors come from the Theatre Lab, a leading nonprofit in DC with a Life Stories program that resonates with the WPA life histories.

What would you say is the legacy of the Federal Writers’ Project? What can we learn from the life histories and individuals who brought them to life?

There are three ways to answer that, I think. The first is essentially economic – to say it provided an unexpected incubator for talent that was otherwise idled by the Depression. The project gave some of the best writers of the 20th century their first jobs as writers at a crucial time.

The second legacy is that, culturally, the project influenced American literature and its dialogue for decades afterward by putting young writers together. For example, the friendship between Richard Wright and Nelson Algren (which I wrote about for American Scholar) bloomed on the Writers’ Project and influenced how both of them depicted America in bestselling novels and films. The project influenced writers like Meridel Le Sueur, who used her interviews with Minnesota women for her novel “The Girl,” about a botched bank robbery; and Margaret Walker’s poetry and novel “Jubilee,” about slavery’s history through one family. Ralph Ellison later cited his early Harlem experiences, when he conducted life interviews for the project, as a seed for the voice and character in “Invisible Man.”

That’s not to say that the life histories just provided material for talented writers, but the project provided many writers with a vital point of engagement with American life. FDR said, “One hundred years from now, my administration will be known for its art, not its relief.”

Maryemma Graham, a professor of English at the University of Kansas and one of our NEH advisors for the film, told Poets & Writers, “The WPA was a godmother or godfather for so many writers who had had few opportunities before that point. For example, the largest single impact on black writing before the civil rights movement was really the WPA, not the Harlem Renaissance.” Graham explains that many Harlem Renaissance writers “did not continue to write after the twenties; Zora Neale Hurston [also a prominent Writers’ Project contributor] and Langston Hughes were the exceptions. Of the WPA writers who were black, more of them developed substantial careers beyond that period.” I was so glad we interviewed Graham for the “Soul of a People” documentary because her commentary is so trenchant.

A third legacy is in historical perspective. With the life histories, the Writers’ Project sort of provided big data for a wider range of perspectives in history, for making history more inclusive. It provided an approach that influenced many writers of history afterward.

Why do you think it’s valuable for the Library to preserve such historical collections, and what do you think the public should know about the Library’s mission to collect and preserve our cultural and historical heritage?

Many writers treat the Library’s collections as a secret trove. The collections offer open access to material where researchers can find new insights that affect how we understand the world. But any visitor gains from visiting the collections. You get a sense of history and its range of viewpoints as a larger view of life. Everyone should know that the Library is theirs to use. For residents lucky enough to live close enough to visit, it just takes five minutes in the James Madison Building to get a researcher’s ID. The generous help of reference librarians in the Main Reading Room puts so much in reach, even if you’re daunted when you enter.

Stetson Kennedy, the Florida folklorist, spoke to that wealth of the Library’s collections in our national life when we interviewed him in his 90s. He recalled a conversation with Alan Lomax, who had made recording tours in the 1930s, hauling a sound machine out to where people lived and worked: soup kitchens, homes, churches and prisons. Back in Washington, Lomax replayed those voices and told Kennedy that he felt was as if they were liberated:

“Alan was telling me how it felt to him later, back in the little room at the Library of Congress, plugging in this machine and listening to a black man’s voice coming out of a prison cell in Rayford, Fla. What an eerie thing it was for that voice and that man’s song to be there in the Library of Congress and echoing in this little chamber.”

For me, Stetson was talking about the Library’s majesty that holds whole worlds for us to find.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers