Library of Congress's Blog, page 156

August 21, 2014

Abraham Lincoln’s “Blind Memorandum”

(The following is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division.)

Could George B. McClellan have become the seventeenth President of the United States? It certainly appeared to be a possibility as Abraham Lincoln assessed the military and political landscape of the United States in the summer of 1864.

President Lincoln understood that his chances of reelection in November hinged on military success in a war now in its fourth year. By the summer of 1864, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had settled in for a prolonged siege against the Confederates near Petersburg, Va., and Gen. William T. Sherman made slow progress toward Atlanta. Confederate Gen. Jubal A. Early, meanwhile, had led his troops to the very gates of Washington, D.C. in July. The war effort seemed to have stalled for the Union, and the public blamed President Lincoln.

The political news for Lincoln was no brighter. Republican insider Thurlow Weed told Lincoln in mid-August 1864 that “his re-election was an impossibility.” Republican party chairman Henry J. Raymond expressed much the same sentiment to Lincoln on Aug. 22, urging him to consider sending a commission to meet with Confederate President Jefferson Davis to offer peace terms “on the sole condition of acknowledging the supremacy of the Constitution,” leaving the question of slavery to be resolved later.

“Everything is darkness and doubt and discouragement,” wrote Lincoln’s secretary, John G. Nicolay, in August 1864. “Our men see giants in the airy and unsubstantial shadows of the opposition, and are about to surrender without a fight.”

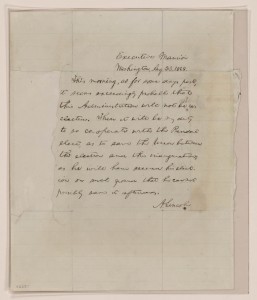

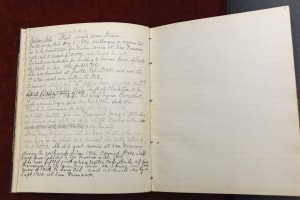

Abraham Lincoln, text of “Blind Memorandum,” August 23, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

It was in this context that Abraham Lincoln wrote the following memorandum on Aug. 23, 1864:

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards. – A. Lincoln

Lincoln folded the memorandum and pasted it closed, so that the text inside could not be read. He took it to a cabinet meeting and instructed his cabinet members to sign the outside of the memo, sight unseen, which they did. Historians now refer to this document variously as the “Blind Memo” or “Blind Memorandum” because the cabinet signed it “blind.” In so doing the Lincoln administration pledged itself to accept the verdict of the people in November and to help save the Union should Lincoln not be re-elected.

As if on cue, Lincoln’s fortunes began to change. As expected, the Democrats nominated George B. McClellan for president on August 30 but saddled him with a “Copperhead” peace Democrat, Representative George H. Pendleton, as a running mate. The Democratic platform declared the war a failure and urged that “immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities,” which even McClellan could not fully support. Then General Sherman scored a tremendous victory when Atlanta fell to the Union on Sept. 2.

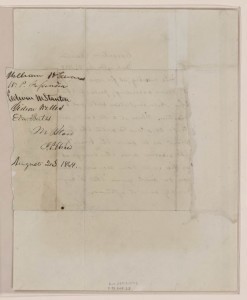

Signatures of Lincoln’s cabinet members on the reverse of the “Blind Memorandum.” Abraham Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

The brighter military outlook, expert political maneuvering by Lincoln and his reinvigorated party (running in 1864 as the National Union Party), and the negatives associated with McClellan and the Democrats spelled victory at the polls for the Republicans. Safely re-elected, Lincoln brought the memorandum with him to the next cabinet meeting on November 11. He finally read its contents to the cabinet, reminding them it was written “when as yet we had no adversary, and seemed to have no friends.”

On its 150th anniversary, the “blind memorandum” reminds us that historical outcomes we may take for granted in hindsight (like Lincoln’s re-election in 1864) do not always appear so certain at the time.

Sources: Abraham Lincoln Papers and John G. Nicolay Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., “Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay”; John C. Waugh, “Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency.”

August 19, 2014

Pic of the Week: En Pointe

Former American Ballet Theatre dancer Sue Knapp-Steen takes in the new Library of Congress exhibition about the professional dance company. 20104. Photo by Ashley Jones.

Last week, the Library of Congress opened the exhibition “American Ballet Theatre: Touring the Globe for 75 Years,” which highlights the dance company’s distinguished history and its collection here at the Library. Shortly after the opening, ABT alum Sue Knapp-Steen (1969-1974) stopped by to view the exhibition and reminisce on her time as a professional dancer with the company during the 1970s.

While with the ballet company, Knapp-Steen toured throughout the United States and Europe, performing the works of choreographers Agnes De Mille, George Balanchine, Michel Fokine, Leonide Massine, Antony Tudor and Kenneth MacMillan in ballets such as “The Nutcracker,” “Swan Lake,” “Giselle” and “Rodeo.”

Knapp-Steen is actually “featured” in the exhibition itself, in a photograph for a 1960 production of De Mille’s “Rodeo.”

Sue Knapp-Steen. October 1971. Photograph by Ken Duncan. Photo courtesy of Sue Knapp-Steen.

“With time’s passage since dancing with ABT, I now realize that the 1960-70s in the world of dance included memorable dancers and ballet companies that flourished, given the burgeoning interest and support for dance in the U.S.,” Knapp-Steen said. “ABT’s international largess of repertoire, choreographers and dancers was a primal force at this time of cross-cultural sharing on all levels. The mix of ABT’s very American-spirited, theatrical works combined with its presentation of timeless story ballets such as ‘Swan Lake’ and ‘Sleeping Beauty’ afforded dancers with ABT its most unique artistic allure.

“Now with ABT’s 75th anniversary, the company continues its dedication to this same spirit of communication and understanding amongst its peers and audiences.”

August 18, 2014

Trending: Happy 100th Birthday, Panama Canal

The seagoing tug, “Gatun” made the first trip through the Panama Canal’s Gatun Locks on Sept. 26, 1913. Prints and Photographs Division

Aug. 15, 2014, marked the centennial of the completion of the Panama Canal, a 48- mile waterway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The canal is a key conduit for international maritime trade.

Plans by the Panamanian government to celebrate the historic event began more than a year ago. A Panama Canal mobile app was launched to communicate about Panama around the world. Educational and cultural institutions in U.S. cities such as Miami and Gainesville, Fla., will also mark the occasion with exhibits. Nearly every cruise line to Panama has one trip scheduled through the canal this year to mark the centennial.

The Library of Congress has a free, 134-page reference guide to Panama materials in its collections. The guide, which is available as a downloadable pdf on the Hispanic Reading Room website, references the wealth of materials available about Panama in the Library’s General and Special Collections (such as maps, manuscripts, newspapers, photographs and legal material). Subjects include civilization and culture, foreign relations, history, literature, politics and government and the Panama Canal. Housed in the Library, the papers of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson contain a wealth of material about the Panama Canal–its construction having spanned their administrations. The papers of Roosevelt’s Secretary of State John Hay and the canal’s chief engineer George W. Goethals, along with the Panama Collection of the Canal Zone Library-Museum (1804-1977), are just a few of the Library’s most significant resources for the study of the canal’s construction.

Following the attempt by the French to construct the canal, the U.S. took over the project in 1904, during Roosevelt’s administration. Panama had become independent of Colombia the previous year, with the help of the U.S. The decade-long project cost the U.S. nearly $375 million to complete, with the aid of more than 45,000 workers, many of whom lost their lives. The majority of workers came from the West Indies and Spain. All told, workers from about 40 countries participated in the construction.

After a period of joint American-Panamanian control, the canal was returned to the Panamanian government in 1999 under the terms of a treaty negotiated by President Jimmy Carter and approved by Congress. The canal is now managed and operated by the Panama Canal Authority, a Panamanian government agency.

This article is featured in the July-August 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

August 15, 2014

But Did The Author Like the Movie?

Poster from the film “Ragtime”

Ever wonder, while watching a film made from a novel you’ve known and loved, what the author of the book thought about that movie? Whether they thought it was true to their vision? Whether they were annoyed at what landed on the cutting-room floor?

Four great modern novelists will share a dialogue on just that topic with Washington Post film critic Ann Hornaday in a session at this year’s Library of Congress National Book Festival on Saturday, Aug. 30 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center.

Titled “Great Books to Great Movies,” the session will feature E.L. Doctorow (recipient of the 2014 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction), Paul Auster, Alice McDermott and Lisa See and run from 8 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. It will be one of the evening events being offered for the first time ever in the 14-year run of the festival.

In addition to the familiar author talks (by 110 authors for readers of all ages and tastes) and literacy-based activities for kids during the daytime hours of the festival, which runs from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., other nighttime offerings include a poetry slam from 6 p.m. – 7:30 p.m., a dialogue on the centennials of three towering figures in Mexican literature (Octavio Paz, Efraín Huerta and José Revueltas) from 6 p.m. – 7:30 p.m. and a “Graphic Novels Super-Session” from 6 p.m. – 10 p.m.

There’s more breaking news on the NBF front – the addition of authors Doris Kearns Goodwin to the lineup in History & Biography and Alan Greenspan in Special Programs.

Doors will open to the public at 9 a.m. on Saturday, Aug. 30 for this fresh new take on a beloved event. The convention center is accessible by subway from the Green and Yellow Lines (Mount Vernon Square/7th Street/Convention Center) and the Red Line (Gallery Place/Chinatown). Don’t miss it!

August 13, 2014

Letters About Literature: Dear Jhumpa Lahiri

In this final installment of our Letters About Literature spotlight, we feature the Level 3 National Honor-winning letter of Riddhi Sangam of Saratoga, Calif., who wrote to Jhumpa Lahiri, author of “The Namesake.”

Letters About Literature, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives, announced its 2014 winners in June. More than 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative, a reading-promotion program of the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress.

National and honor winners were chosen from three competition levels: Level 1 (grades 4-6), Level 2 (grades 7-8) and Level 3 (grades 9-12). You can read all this year’s winning letters here. In addition, winning letters from previous years are available to read online.

Dear Ms. Jhumpa Lahiri,

As an Indian girl growing up in America, in a culture that is predominantly Caucasian, I always felt like I was slightly apart from my peers, as if there was a barrier between myself and everyone else. I remember a time when I was six years old, in the first grade, when I was eating lunch with my classmates. My mother had packed Indian bread, chapathi, and cubes of cottage cheese cooked in creamed spinach, palak paneer. The other children looked at the food and said, “Ew! That’s gross!” I still remember putting the lid on my Tupperware container and closing my lunch box, determined not to cry.

After that, I begged my mother to send me peanut butter and jelly sandwiches — American food, food that everyone else ate — for lunch. My mother readily agreed, but I can see now that my rejection of Indian food symbolized something more to her; a wish not to be associated with Indian culture.

I wanted to be American. I wanted sandwiches and pasta and food that did not provoke disgusted looks from my classmates. I wanted to have blue eyes and a name that was easy to pronounce, a name not vulnerable to a gamut of creative mispronunciations. When people tried to pronounce my name for the first time, I would apologize embarrassedly for my culture, saying, “My name is Indian. Sorry.” I did not realize, however, that in wishing all of these things, I was rejecting my heritage and all of the sacrifices my family members had made so I could live a happy life.

Because I felt alienated from my peers for most of my childhood, I believed a happy life was one where I was not an outlier, a life where I was simply the same as all of my classmates. I reasoned that although I could not change my name to make myself fit in with the rest of my peers, I could mimic my classmates in dress. I did not want clothes that could provoke my peers to say, “That shirt’s so … interesting,” and I did not want clothes that were too “Indian-looking” — anything paisley-patterned or anything that was excessively embroidered was put into this category. I wanted specific shirts, the shirts everyone wore, the ones that were emblazoned proudly with logos, logos that seemed to proclaim that I was jut like the rest of the children. I remember shopping for these shirts, hearing my parents say, “Why do you even want these shirts? You know, when I came to America, I never would have spent so much money on such frivolous items. You know what I did instead? I cut coupons. I walked miles in the snow from the grocery store to my tiny apartment because I didn’t have a car. I had permanent welts on my fingers from the plastic grocery bags straining against my hands. Do you ever think of that, Riddhi?”

I was extremely conscious about my heritage until the tenth grade, when a group of students in my English class, including me, was assigned to read ‘The Namesake.’ Although I love to read, I did not think that I would enjoy the book — I normally do not enjoy books that come with assignments and reports due for school. This preconception changed as soon as I read the first few pages and immediately saw my parents in Ashima and Ashoke, and later, myself in Gogol and Moushumi.

Reading the book was like reading an echo of myself. I empathized with Gogol’s struggles to find an identity with which he could be content; Moushumi’s struggles to please her parents; and finally I realized what my parents had given up so they could create a good life in America.

As I read about Gogol and how he detested his name, the way his peers, meaning well but not understanding, mispronounced the letters, I felt a kinship. I saw myself in the way he strived not to be associated with Indian culture, the way he fought so hard to break the bonds between himself and his roots.

I identified with Moushumi’s decision to pursue a degree in French — my forte has always been languages and the humanities, and in a family composed of doctors, engineers, and businesspeople, my strengths have been treated like a hobby, something to do on the side, not to be taken seriously. “Riddhi?” She’s good at French. But what can you do with a degree in French? Nothing, that’s what!”

But I was most enlightened by reading about Ashima’s and Ashoke’s lives and the sacrifices they made. My parents told me about the life they had when they immigrated to America — cutting coupons; walking for miles in the snow because a car was too expensive; and living in a tiny one-bedroom apartment — but when I heard these stories, I dismissed them. When I read about Ashima trying to recreate chaat in her kitchen in America, I envisioned my parents when they arrived in America, trying but failing to recreate the lives they had had in India, failing because, “[...] as usual, there [was] something missing” (Lahiri 1). As I read about Ashima’s efforts to assimilate into American culture, I imagined my parents, lost and confused in American after sacrificing the comforts of Indian for a life of cutting coupons and walking in the snow.

I no longer desire blue eyes; I no longer desire a different name. As Gogol realizes and as I realized, “The name he had so detested [...] that was the first thing his father had given him” (289). As I read these words, I understood, just as Gogol understands, that my name is the most important thing I have ever received, for my name is the embodiment of my parents’ sacrifices, my parents’ cooking, my parents’ sotires, my culture; my identity. I understood that my name and subsequently, my culture, is not something just to be rejected; instead, it is something to embrace, because my name stands for all of the past generations in my family, and all of the sacrifices they have made — such as immigrating to American when Indian held the comforts of home — so that I could have the best life possible.

Now, I bring Indian food to school for lunch. Now, I wear clothes I previously deemed “too Indian-looking” to school. Now, when people have difficulty pronouncing my name, I say proudly, “My name is Indian.”

Thank you, Ms. Lahiri, for making me finally realize that my heritage is my identity. Thank you for making me realize that my culture and my heritage are the most important parts of me.

Riddhi Sangam

August 8, 2014

Library in the News: July 2014 Edition

The Library of Congress had two major announcements in July, featuring well-known public figures, that garnered several headlines.

Billy Joel was named the next recipient of the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

Stories ran in Rolling Stone, the Dallas Morning News, The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Today Show.

Joel was also featured as ABC World News Tonight “Person of the Week.”

In addition, on July 29, the Library opened to the public a collection of letters between President Warren G. Harding and his mistress, Carrie Fulton Phillips.

“Every so often, we get a poignant reminder of what has been lost now that letter-writing has been replaced by texting, emoticons or nothing at all, if you’re a politician afraid to commit anything to paper for fear it will show up on page one or be read aloud by a committee chairman on a tear,” wrote Margaret Carlson for Bloomberg. “This makes the trove of love letters written by Warren Harding, to be unsealed at the Library of Congress and published online this month, all the more appealing.”

“The roughly 900 pages illuminate an extraordinary and intimate chapter in the life of a seemingly drab president who was dogged by political scandal, died in office and had campaigned on a platform of ‘a return to normalcy,’” wrote Washington Post reporter Michael E. Ruane.

ABC News covered a panel discussion a week before the public opening that featured historians and Harding’s grandnephew discussing the letters.

Also running stories were Slate, the New York Times Magazine and the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Several news outlets turned their headlines to the Library itself, taking a look at its buildings and services.

“I can’t leave Capitol Hill without fulfilling a dream to get a library card at the Library of Congress,” wrote Robert Reid for National Geographic. “After a look at the Jefferson Building’s exhibits (an early U.S. map shows Connecticut as a long rectangle extending toward the Mississippi), I make a tunnel walk or two between neighboring wings and find myself with a new Library of Congress Reader Card.”

PBS Newshour ran a piece on the Library’s efforts to restore Thomas Jefferson’s library.

“Sixteen years ago, Mark Dimunation and his team set out to restore Jefferson’s collection, replacing the lost books with copies from the same publisher, date, and edition,” reported Jeffrey Brown. “Green ribbons denote books from the original library. Gold are copies that serve as replacements. The white or ghost boxes are placeholders for the 250 books still being sought.”

And, finally, local ABC affiliate WJLA captured a remarkable photograph of what appeared to be a lightning bolt striking the Library’s Jefferson Building dome. There were no reports of damage or injury from the alleged strike.

August 7, 2014

Clocking In

John Flanagan’s clock. Photo by Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building opened to the public in 1897. Hailed by a guidebook as a “gorgeous and palatial monument to its [America’s] national sympathy and appreciation of literature, science and art,” the construction of the edifice was a feat in and of itself – more than 15 years of postponements, major architectural changes and an assortment of hang-ups marked its debut to the nation.

In fact, Superintendent of Construction Bernard Green wouldn’t consider the building finally complete until Aug. 9, 1902, with the placement of the ornate clock in the Main Reading Room, according to an entry in his journal.

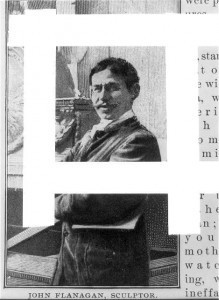

A focal point of the symbolic epicenter of the Library, the clock was designed and crafted by American sculptor and medalist John Flanagan (1865-1952). Flanagan accepted the commission on October 1, 1894, and Green proposed the “Flight of Time” as the subject. Neither could have imagined the clock would take more than seven years to complete.

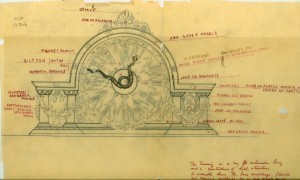

Flanagan’s original design in May 1895 contained exact notes on materials and placement of the clock’s elements. For example, the rosettes surrounding the clock face were to be pink or purple marble with a lapis lazuli center. The hands of the clock were to be serpentine and set with precious stones. (The snake design of the hands did not, in fact, make it into the final piece.)

Flanagan’s original design contained exacting notes on materials and placement. Not included in the final piece were the snake hands shown in this drawing. Manuscript Division.

Aside from the dial structure, Flanagan was committed to incorporating mostly sculptural elements to the clock, emphasizing not only time but also its relation to knowledge. Symbolic elements included seated bronze figures on each side of the dial representing study (“Sitting Students”), the “Flight of Time” above the dial featuring Father Time and attendant seasons, a mosaic back piece with signs of the zodiac and a circular panel below the dial with a bas-relief of the “Swift Runners” who “keep the light of knowledge circulating.”

Flanagan continued to revise his sketches and his work dragged on – so much so that Green threatened to cancel the commission if the clock was not complete and in place by Jan. 1, 1897. Flanagan wrote to Green saying he was working as fast as he and his assistants could “push it.” He assured the superintendent that the mosaic with zodiac signs and dial structure would be ready but the larger bronze sculptural elements would take more time.

John Flanagan. Prints and Photographs Division.

By April 20, 1897, the clock’s mosaic background and dial structure were put in place in the Main Reading Room. It would take another year for the “Sitting Students” and “Swift Runners” to arrive and another two-and-a-half years for the “Flight of Time” to be finished and delivered.

In late July 1902, Green wrote in his Journal of Operations, “Having been made very wide with spreading eagle wings and so high as to overlap the architrave, and being about 1600 lbs. weight the job is an extremely difficult one,” documenting the placement of the “Flight of Time” sculptural element. Over the next few weeks, Flanagan was on hand to supervise the installation, and, according to Green, was “nosing about” and fussing over various details regarding his creation.

Flanagan also designed the statue of Commerce, which can be found in the Main Reading Room as well.

For more information on the history of the Library of Congress and its buildings, see “Jefferson’s Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress” and “On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress.”

Searching the Library’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog for “Library of Congress” brings forth numerous images of the construction of the Jefferson Building and its architectural drawings, as well as vivid color photographs of the Library’s Capitol Hill campus and buildings interiors.

August 5, 2014

Global Gathering

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library’s staff newsletter, The Gazette, for the July-August 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.)

The sun truly never sets on collecting at the Library of Congress. At any given hour, somewhere on the planet, an employee is acquiring material to add to the world’s largest library.

Scattered across 11 time zones, from Brazil to Indonesia, the Library’s six field offices acquire hard- to-get publications from developing nations for its own collections and those of other U.S. and global research institutions. It’s a vast undertaking that requires knowledgeable people at the source. Wherever material is published—be it Syria, Pakistan, Cambodia, Rwanda, Nepal or Suriname—the Library of Congress is, in some fashion, there.

“Really, for much of what we collect, no other libraries do so on this scale,” said William Kopycki, director of the Cairo field office. “We’re the only library in the world that has this concept of overseas offices.”

Librarians in Rio de Janerio work at the Rio Book Fair at a booth constructed from recycled paper. Overseas Operations Division.

In the years following World War II, the Library and U.S. academic institutions recognized the importance developing regions would play in a changing world—and the need to better understand the history, politics, religion and culture of these far-flung places. So, the Library, beginning in the early 1960s, established nearly two-dozen field offices around the globe. Today, six remain, in Cairo; Islamabad; Jakarta, Indonesia; Nairobi, Kenya; New Delhi and Rio de Janeiro. Their mission: supply the Library and other research institutions with tough-to-acquire primary materials from developing regions to ensure Congress, analysts and scholars get critical information.

A WORLD OF CHALLENGES

Carrying out that mission in developing countries presents serious challenges. War, terrorism, political unrest, censorship, poverty, huge geographic distances, scores of languages, underdeveloped infrastructure, unreliable power grids and a lack of publishing standards all pose difficulties.

In 2011 and again in 2013, massive, violent political protests forced the temporary closure of the Cairo office and the evacuation of its director, Kopycki, from Egypt. The U.S. State Department at times denied approval for acquisition trips for fear that an airport would close and leave Cairo employees stranded – decisions, Kopycki said, “made to keep us safe.”

Islamabad is risky enough that the director oversees that office from 430 miles away in New Delhi, flying back to Pakistan’s capital city several times a year. The Library’s office in Nairobi is located in the U.S. embassy complex built after the 1998 bombing of the old embassy. Last year, terrorists attacked a shopping mall in Nairobi, killing nearly 70 people.

“Just coming into work can be challenging, given the critical threat faced by this country with terrorism,” said Pamela Howard-Reguindin, former director of the Nairobi office, who now heads the Islamabad office.

AT THE SOURCE

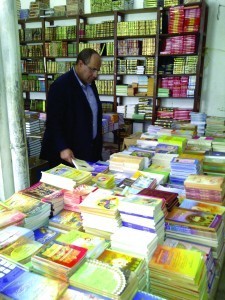

Ismail Soliman, former head of monograph acquisitions in the Library’s Cairo office, searches for library materials in a bookshop in Mauritania. Overseas Operations Division.

Despite the difficulties, the overseas offices collect a huge range and volume of material: government documents, newspapers, magazines, academic journals, monographs, books, maps, DVDs, CDs and, in recent years, websites—in all, more than 663,000 items in fiscal year 2013.

The offices also cover a vast geographic and linguistic range. In the last fiscal year, they acquired and cataloged material from 79 countries in about 120 languages. Such an effort requires knowledgeable people at the source, wherever on the globe it may be.

“The only way to get some of these materials is to be there and pick them up as they come hot off the press, so to speak,” said Beacher Wiggins, who directs the overseas offices for the Library of Congress. “Particularly in areas where there may be dissident views or dissident groups that challenge the government or espouse a different view, you wouldn’t get these through normal publishing channels. By the time you got that kind of information, it would be two or three years later. Firsthand scholarship would suffer. Congress wouldn’t necessarily get firsthand accounts of what’s going on.”

LOCAL KNOWLEDGE IS KEY

Each office is led by an American director and staffed by locals—about 240 in total—who serve as librarians, catalogers, accountants, information technology specialists, shipping clerks and drivers. Most of the catalogers and librarians have library science degrees or advanced degrees.

The local employees’ knowledge and linguistic skills are invaluable in navigating the myriad cultures and languages, the huge geographic spaces and the sometimes-tricky political terrain. They also possess another important skill: They know what to get and where and how to get it.

“Because the staffers are local, they know the language, they know the culture,” Wiggins said. “They know when it might be imprudent to advertise that they are collecting as a U.S. government employee.”

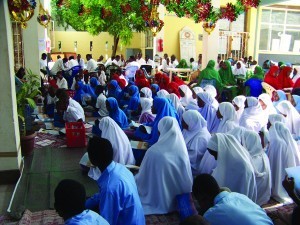

Students listen to a story being read aloud at the Somali-English family literacy story hour at the USAID-sponsored Garissa Youth Summit in Northeastern Kenya. Photo by Nancy Meaker.

Each overseas office covers a group of countries in its region. The Jakarta office, for example, collects from Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar (Burma), the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Vietnam. The Nairobi office covers 29 countries over a gigantic swath of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Material is gathered through a blend of methods—relationships with commercial vendors, bibliographic representatives who collect on the offices’ behalf and acquisitions trips made by field office staff.

“We do know the sources, where to get things,” Kopycki said. “It’s how to engage to get the things that are really unique and special.”

The materials they choose—in collaboration with the collections divisions in the Library’s Capitol Hill offices— are selected for the quality of scholarship, the importance of subject and the extent to which it adds to the knowledge of a topic. Sometimes they represent new cultural trends, such as graphic novels produced in North Africa and drawn in Japanese anime style. Other material frequently is controversial and from underground sources.

“We spent the last couple of years in particular since the Egyptian revolution gathering ephemera and pamphlets,” Kopycki said. “This culture of publishing ephemeral materials with heavy political tones was really unknown in Cairo the past 30 years.”

SHARING WITH THE GLOBE

Many institutions benefit from the hunting and gathering done by the Library’s local employees.

The offices provide material—some 375,000 items in the last fiscal year—to 80 other U.S. institutions and 24 foreign institutions through the Cooperative Acquisitions Program. Those institutions could acquire major commercial publications from some developing nations on their own. The Library field offices do what they can’t: acquire less-accessible material and items from harder-to-cover countries.

“That’s really a unique service, not just for our parent institution but for our participant libraries as well,” Kopycki said. “We’re acting as their eyes and ears to get materials that otherwise are not readily available.”

All that collecting requires a lot of other work— cataloging, accounting, processing, packing and shipping—to make sure everything arrives safely and in the right place. Shipping is a big part of what the offices do. In fiscal 2013, they collectively shipped about 180 tons of material by sea and air freight to the Library and Cooperative Acquisitions Program participants.

A lift van in New Delhi is loaded with publications for shipment to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Overseas Operations Division.

“It’s all these things that you don’t picture a traditional librarian doing that our staff does in order to make sure that book, that newspaper, that DVD arrives in the hands of a researcher in Washington,” Kopycki said.

The flow of that material, gathered at the source in countries around the globe, helps ensure that the Library of Congress, and other libraries, have the firsthand resources Congress, analysts and scholars need now, and decades in the future.

“These areas still are in turmoil and, in some instances, changing their worldview or becoming a powerhouse,” Wiggins said. “The overseas offices are critical in supplying Congress information as well as supplying research materials scholars might need 10, 50, 100 years from now.”

Download the July-August 2014 issue of the LCM in its entirety here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

August 4, 2014

Semper Paratus, Always Ready

Setting the course to victory with the U.S. Coast Guard / L.W. Bentley, U.S.C.C.R. Prints and Photographs Division.

Most people know the United States Coast Guard as a military branch that provides local maritime safety and law enforcement, with service men and women patrolling America’s shorelines and answering distress calls after boating accidents. However, the USCG has incorporated a number of functions throughout its more than 224-year career as the “oldest, continuously serving sea service.”

Today’s Coast Guard is actually an amalgamation of five former independent Federal agencies: the Revenue Cutter Service, the Lighthouse Service, the Steamboat Inspection Service, the Bureau of Navigation and the Lifesaving Service.

The Coast Guard’s official history began on Aug. 4, 1790, when President George Washington signed the Tariff Act that authorized the construction of 10 vessels. The United States Revenue Cutter Service, as it became known, used these vessels, or “cutters,” to enforce federal tariff and trade laws and to prevent smuggling.

First Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton actually proposed the “system of cutters” and urged Congress to establish this service as the new nation was struggling financially following the Revolutionary War.

“A few armed vessels, judiciously stationed at the entrances of our ports, might at a small expense be made useful sentinels of the laws,” he wrote in the essay “The Utility of the Union in Respect to Revenue,” part of The Federalist Papers.

The Library has a very significant collection of Hamilton’s papers. In fact, a few years ago, the institution received a gift of a letter written by Hamilton that concerns the per diem payments for rations issued to seamen on board the cutters.

“This is certainly not the most significant letter Alexander Hamilton ever wrote,” explained Julie Miller, early American specialist in the Library’s Manuscript Division. “It is important, however, because it shows Hamilton at work establishing the operating procedures of the Revenue Cutter Service very soon after it was founded.”

Hopley Yeaton commission signed by Washington and Jefferson. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

The Manuscript Division also holds the March 21,1791, certificate signed by President George Washington and countersigned by Thomas Jefferson as secretary of state commissioning Hopley Yeaton as the first officer of the Revenue Service.

The service expanded in size and responsibilities as the nation grew. Because the Continental Navy was disbanded in 1785, the Revenue Service was the only maritime force available to the new government. The cutters also served as warships protecting the coast. Since then, the Coast Guard has fought in almost every war since the Constitution became the law of the land in 1789.

Other responsibilities of the cutter service included protecting the country’s strategic natural resources with the Timber Act of 1822, cruising coastlines for those in distress and, after the Titanic sank in 1912, conducting international ice patrols.

Revenue Cutter Bear at Sitka, Ala. 1890-1900. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Coast Guard has helped to protect the environment for more than 180 years. With the purchase of Alaska in 1867, the ecological responsibilities of the Revenue Cutter Service were greatly increased. Sealing was a huge problem as fur seals were being hunted into extinction due to the value of their coats.

The Library’s Manuscript Division holds records from the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, including a journal and letter book detailing voyages of several cutters. In entries dated 1889-1890, mentions are made of the cutter Bear and its Alaskan patrols looking for sealers and its efforts in tamping down the illegal seal trade.

The Library’s collection of papers of Naval officer Elliot Snow includes notebooks from Horatio D. Smith, who was an officer in the Revenue Cutter Service. Smith also documented voyages of various cutters, including the cutter Golden Gate doing “good service” during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and transporting President Taft across the bay in 1909, and the cutter McCullough being the first to pass through the Suez Canal.

Notebook documenting voyages of cutter Golden Gate. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

In 1848, Congress passed an appropriation for $10,000 to allow for “the better preservation of life and property from shipwrecks.” This system eventually grew into a federal agency called the United States Life-Saving Service. Operating from small stations throughout the nation, the service saved tens of thousands of people in distress between 1878 and 1915.

In 1915, an act of Congress merged the Revenue Cutter Service with the U. S. Life-Saving Service, and thus the U.S. Coast Guard was born. The nation now had a single maritime service dedicated to saving life at sea and enforcing the nation’s maritime laws.

Additional agencies were later merged into the Coast Guard.

While the cutter service was established in 1790, Congress had created the Lighthouse Establishment the year before – only the ninth law passed by the new government – and took federal jurisdiction over lighthouses then in existence. It continued to exist as a separate agency within the Treasury Department until 1939 when President Franklin Roosevelt ordered its transfer to the Coast Guard. With this executive order, the Coast Guard began to maintain the nation’s lighthouses and all maritime aids to navigation.

The Steamboat Inspection Service and the Bureau of Navigation existed separately before being combined in 1932 and reorganized and renamed in 1936 as the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation. Essentially both provided for safety inspections and the safeguarding of life and property while at sea.

During World War II President Roosevelt transferred the bureau to the Coast Guard and in 1946 the shift was made permanent, thereby placing merchant marine licensing and merchant vessel safety under the service’s purview.

U.S. Coast Guard Cutter WHITE SUMAC. Prints and Photographs Division

In 1967 President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered the Coast Guard transferred from the Department of Treasury, where it had been since the Revenue Cutter Service was founded, to the newly created Department of Transportation. Following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the Coast Guard was again transferred by executive authority when President George W. Bush moved the military branch to the newly established Department of Homeland Security.

Other Coast Guard-related resources at the Library include the USCG Historian’s Office Collection,; the papers of Charles Frederick Shoemaker, who was chief of the Revenue Cutter Service in the early 1900s; and the diary of William Cooke Pease, service officer, written while in command of the cutter Jefferson Davis on voyage from Charleston, S.C., to San Francisco, Calif.

In addition, searching the Prints and Photographs Online Catalog for “coast guard” will deliver a variety of photographs. As part of the Veterans History Project’s “Experiencing War” series, read and listen to first-person accounts of men and women who served in the USCG.

August 1, 2014

Junior Fellows Show Off Summer Finds

(The following is an article written by Rosemary Girard, intern in the Library of Congress Office of Communications, for the Library staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

Abigail Weaver of CALM demonstrates her work with miniature books from the Library collections. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

After weeks of researching, curating and unearthing some of the Library of Congress’s millions of artifacts, members of the Junior Fellows Program had a chance to present their most interesting finds.

During an open-house display in the Jefferson Building last week junior fellows shared the culmination of their 10-week internship at the Library. The displays were organized by division, flowing from copyright materials to African and Middle Eastern artifacts, from sheet music to legal documents. In many ways, moving through the junior fellows showcase mirrored a tour of all the Library’s divisions, missions, and offerings.

Among the artifacts on display were examples of pulp fiction from the 1930s; a check from Marilyn Monroe to actor, director and acting teacher Lee Strasberg for $90 (1955); an audition sheet showing Al Pacino’s first audition for the Actors Studio (1961); hard copies of the Batman and Green Lantern comic book editions; and a letter written by Winston Churchill’s daughter-in-law describing the events of D-Day.

Julie Rogers, who worked in the Serials and Government Publications Division, described the importance of the pulp fiction collection she displayed.

“Many people do not realize the Library of Congress collects popular-culture items such as the pulp magazines or comic books,” she said. “These collections are essential if the Library is to preserve the true complexity of American creativity and knowledge.”

In addition to the physical artifacts on display, many junior fellows presented their work on monitors or iPads, demonstrating Library digital initiatives in action.

The event provided the opportunity to learn from the junior fellows about some of the connections and stories behind these treasured items.

Ayana Bowman and Miguel Castro presented an English/Spanish online display telling the story of the Mexican Revolution and its impact on the U.S. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

Walton Chaney, for example, conducted outreach for the Veterans History Project (VHP). In his time as a junior fellow, he helped create a system through which Congressional offices can partner with the Library to make veterans visiting Capitol Hill offices aware of VHP and encourage them to share their stories.

“I have seen how liberating the experience of telling one’s story can be on a personal level, as well as enlightening to others,” Chaney said. “This idea of encapsulating the human experience of war ensures that our nation’s veterans and their efforts will never be forgotten.” At the showcase, Chaney displayed a video interview of the last remaining World War I veteran, Frank Buckles, who died in 2011.

Each year, the Junior Fellows Program allows undergraduate and graduate students to explore and increase access to the Library’s collections and resources. The 2014 program specifically focused on increasing access to the Library’s special, legal and copyright collections, making them better known and available to researchers through digital service and preservation projects.

The program is made possible through the generosity of the late Mrs. Jefferson Patterson and the Knowledge Navigators Trust Fund with additional support provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers