Library of Congress's Blog, page 152

December 3, 2014

The Warrior Poet (a.k.a. Fellow Traveler No. 1)

Former Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish greets Marquess of Lothian at WWII ceremony displaying Magna Carta at the Library

Many larger-than-life figures have served as the Librarian of Congress. As the Library once again plays host to that seminal document affirming the rule of law, Magna Carta, today we shine a spotlight on the man who was Librarian of Congress when the great charter first visited the Library – Archibald MacLeish.

MacLeish, before his long life (1892-1982) ended, worked as a lawyer, a professor, and a founder of UNESCO in addition to his main profession as a poet and playwright. He won two Pulitzer Prizes, a Bollingen Prize and a National Book Award for his poetry, in addition to a Pulitzer Prize for drama.

MacLeish, who came from a comfortable background in Illinois, wrote poetry in high school and during his undergraduate years at Yale. He served as an artilleryman in World War I, then returned to the U.S. to study law at Harvard; after receiving his degree he worked as a lawyer for about three years.

Then he and his wife, Ada, decided to decamp for Paris, so he could devote his efforts to poetry and she could focus on singing. There, they hung out with American expats including Ernest Hemingway, Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound and other noted writers and poets. MacLeish became a focused anti-fascist as he watched developments around Europe during the late 1920s and 1930s.

From 1920 to 1938, MacLeish struck a deal with publishing magnate Henry Luce, agreeing to serve as editor of Fortune Magazine if MacLeish could carve out enough time to keep working on his poetry. In 1932, he won his first Pulitzer in poetry. He wrote more and more about the threat posed by fascism.

In 1939, with Franklin Delano Roosevelt in office, MacLeish was recommended for the post of Librarian of Congress by Felix Frankfurter, a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

FDR offered and MacLeish took the job – his predecessor had held it for nearly four decades - and presided over a reorganization of the Library. As war loomed, however, he led the institution toward a role as a “Fortress of Freedom,” emphasizing new roles for the Library including safeguarding such documents as Magna Carta (originally on loan from England to be exhibited at a world’s fair and at the Library, the British and the Library agreed to send it to Fort Knox for its own protection when the U.S. entered WWII, for the duration of the war); creating a reference agency for the support of the Office of Strategic Services, which later became the CIA; and supporting Congress and federal agencies in their needs for war-related information.

Also, appropriately, he presided over the creation of the Library’s Poet Laureate, Consultant in Poetry

Former Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish greets Marquess of Lothian at WWII ceremony displaying Magna Carta at the Library

position, which previously did not exist. Although MacLeish is responsible for the laureateship being a short-term, revolving gig – he wasn’t a fan of the poet originally suggested by the donor who put up the money for the program – he kept it all on a professional basis, including naming one poet, Louise Bogan, who had criticized MacLeish’s poetry in earlier years. When she pointedly asked him why he’d chosen her, he replied that she was the best person for the job.

He served as Librarian until 1944. In 1945, MacLeish went to the State Department as an assistant secretary of state for cultural affairs, then helped draft a constitution for UNESCO and served on its executive council. From 1949 forward, he wrote poetry and plays and taught. He served in the mid-1950s as president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Here are two of his many poems: “Ars Poetica” and “An Eternity.’ He is also well-known for his play, “J.B.,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1959.

Cornell History Prof. Robert Vanderlan writes that MacLeish was controversial in the 1940s and 1950s – both with the left, which accused him of holding “unconscious” pro-fascist views and with sympathizers of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Vanderlan writes that MacLeish was the first American to be dubbed a “fellow traveler” by HUAC’s chairman, Rep. J. Parnell Thomas.

MacLeish was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and the National Medal for Literature in 1978. He died, in Boston, in 1982.

December 1, 2014

My Job at the Library: David Mao

(The following is an article in the November/December 2014 issue of LCM, the Library of Congress Magazine. The issue can be read in its entirety here.)

David Mao. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

Law Librarian of Congress David Mao discusses his career path to the world’s largest law library.

What are your responsibilities as Law Librarian of Congress?

I see the position as having three very broad responsibilities. I am part law librarian to Congress, part steward for the law collections at the Library of Congress and part ambassador to the world’s legal and library communities. As Law Librarian, I manage the operation and policy administration of the world’s largest collection of legal materials and of the leading research center for foreign, comparative and international law.

Can you describe the career path that led you to this position at the Library?

During my second and third years of law school, I worked as a student aide in the library. I really enjoyed working in the library. When graduation neared, I consulted with two of the librarians about a possible career in law librarianship. I was advised that I would need to complete a library degree. Deciding to be fiscally prudent, I took a slight detour–for the next several years, I toiled for a large law firm, working on commercial litigation matters.

A chance encounter presented me with the opportunity to work in an academic law library again. I took the opportunity and thereafter applied to library school. A year later, I applied for and was given a position as legislative librarian in the D.C. office of an international law firm. I tracked and monitored current federal legislation, provided in-depth research on historical legislation, and also compiled and prepared legislative histories. I also continued my studies and received a library science degree. After almost eight years at the firm in various positions, including managing research and conflicts, I moved to the Library’s Congressional Research Service. In 2010, I joined the Law Library as Deputy Law Librarian, and then became Law Librarian in 2012.

Why did you want to work at the Law Library of Congress?

The opportunity to work with the world’s largest collection of legal materials is a primary reason. In addition, I am able to work with the Law Library of Congress team–a high-caliber group of people who are very respected in the community and around the world. As the Law Library is a part of the larger Library of Congress, I have the added pleasure and honor to work with colleagues who together are leading the library profession in the Age of Information. I am always in awe to be among the leaders in the areas of information, policy, preservation and research–right here at the Library of Congress.

What is the most interesting fact you’ve learned about the Law Library?

One interesting fact is that, pursuant to the Standing Rules of the Senate, “the Assistant Librarian in charge of the Law Library” has privilege of the Senate floor. Access to the Senate Chamber floor is a privilege not accorded to many non-members of Congress.

How have you used your fluency in Chinese in your profession?

I believe that it is important to be involved in professional associations. As an outgrowth of work with the American Association of Law Libraries, I joined with several law librarian colleagues to help found a non-profit organization to promote the accessibility of legal information and foster the education of legal information professionals in the United States and China. Working with the organization has allowed me to use my Chinese language skills as well as my academic background in international affairs, law and librarianship.

November 26, 2014

Trending: A White Christmas

(The following is an article in the November/December 2014 issue of LCM, the Library of Congress Magazine. The issue can be read in its entirety here.)

As the holidays approach, the dream of a white Christmas is on many minds.

The cast of “White Christmas” poses on this 1954 movie poster. Paramount Pictures Corporation, Prints and Photographs Division.

A white Christmas is the stuff that dreams are made of, at least according to composer and lyricist Irving Berlin (1888-1989).

Berlin’s “White Christmas” was written for the movie musical “Holiday Inn,” starring Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. The first public performance of the song was by Crosby, on his NBC radio show “The Kraft Music Hall” on Christmas Day 1941. The song rapidly became a wartime tune for those fighting abroad and for those on the home front. By the time the film debuted in the summer of 1942, the song was on its way to becoming the best-selling single of all time. It garnered the Academy Award for Best Original Song of 1942.

The Irving Berlin Collection in the Library of Congress–750,000 items–documents all aspects of his life and career. The collection contains music scores, Berlin’s handwritten and typewritten lyric sheets, publicity and promotional materials, personal and professional correspondence, photographs, business papers, legal and financial records, scrapbooks filled with press clippings, awards and honors and artwork. Among these items is the lead sheet sketch of “White Christmas,” dated Jan. 8, 1940–though not in Berlin’s own hand since he didn’t write musical notation.

The popular song also became the inspiration for the 1954 movie musical, “White Christmas.” With a similar plot involving a country inn, “White Christmas” paired Crosby with Danny Kaye. Still images from the film came to the Library as part of the Danny Kaye and Sylvia Fine Collection.

The collection of more than 1,000 boxes of materials (sheet music, scripts, business papers, correspondence, photographs, recordings and videos) came to the Library in 1992. The Library’s 2013 exhibition “Danny Kaye and Sylvia Fine: Two Kids from Brooklyn” featured items from the collection.

Score and cover for “White Christmas,” Irving Berlin Music Corporation, 1940. Music Division.

The original 1942 Bing Crosby recording of “White Christmas” was added to theNational Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in its inaugural year, 2002.

The opening verse, dropped from the original version, may prove that the song was written in California.

“The sun is shining, the grass is green,

The orange and palm trees sway.

There’s never been such a day

in Beverly Hills, L.A.

But it’s December the twenty-fourth,–

And I am longing to be up North–“

November 24, 2014

A Prize for the Piano Man

Billy Joel accepts the Gershwin Prize from Librarian of Congress James H. Billington and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Photo by John Harrington.

Last Wednesday, the Library of Congress celebrated the music and career of singer-songwriter Billy Joel, awarding him the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. A star-studded cast walked a packed house at the DAR Constitution Hall through Joel’s own songbook during a tribute concert. I myself had the honor and privilege to also take the stage as a sort of “opening act” for Joel while performing with the Library of Congress Chorale. It was a once in a lifetime experience to be able to honor such a music legend.

Twyla Tharp. Photo by Amanda Reynolds

The following is a recap of the concert, written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress newsletter, The Gazette.

The Library of Congress honored rock and roll’s piano man with its Gershwin Prize for Popular Song on Wednesday night, with a little help from his friends.

“This is kind of verklempt,” Billy Joel told the audience during a concert at DAR Constitution Hall that featured more than a half-dozen stars performing some of his most-loved tunes. “This is something that’s very, very important to me and very, very valuable. I’ll always treasure this.”

Members of the Twyla Tharp Dance company. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Joel composed and recorded 33 top-40 songs during his career, a string of hits that spanned three decades and inspired generations of fans: “Piano Man,” “Just the Way You Are,” “Movin’ Out,” “Only the Good Die Young,” “Big Shot,” “You May Be Right,” “It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me,” “Allentown,” “Uptown Girl,” “An Innocent Man,” “The Longest Time,” “Keeping the Faith” and “A Matter of Trust,” among many others.

On Tuesday, Joel attended a luncheon at the Library, took a tour of the Main Reading Room, viewed a collection of Library treasures and stopped at the Gershwin display in the Jefferson Building, where he played a few tunes on Gershwin’s piano.

Tony Bennett. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

On Wednesday, Academy Award-winning actor Kevin Spacey, choreographer Twyla Tharp and singers Tony Bennett, Boyz II Men, Gavin DeGraw, Michael Feinstein, Josh Groban, Natalie Maines, John Mellencamp and LeAnn Rimes took the stage to celebrate Joel and his songs’ memorable melodies and characters.

Following a performance by the Twyla Tharp Dance company, Spacey greeted the audience and lauded the Library as a “beacon of American culture” and the “world’s largest repository of human knowledge and creativity.”

“That’s right: I said ‘repository,’” Spacey quipped, “not that other word some of you were thinking I said.”

Then, taking on his villainous “House of Cards” character, Spacey welcomed the guest of honor, seated above the stage between Librarian of Congress James H. Billington and Supreme Court Associate Justice Sonia M. Sotomayor.

Gavin DeGraw (left) and longtime Billy Joel bandmate Mark Rivera. Photo by Shawn Miller.

“I think even a man like Frank Underwood would be pretty excited about a night like tonight,” Spacey said in his slow Underwoodian drawl. “So, Billy, here’s to you. Let’s start the show.”

Via video, Joel received tributes from two of his great pop contemporaries, Barbra Streisand and James Taylor, and one fellow Gershwin Prize-winner: Paul McCartney.

“This is an award you very much deserve,” McCartney said. “This is from a great American composer of the past to a great American composer of the present. … I love your music.”

Boyz II Men delivered a finger-popping a cappella performance of “The Longest Time” that kicked off a string of some of Joel’s biggest and best-loved hits: “Lullabye” (Rimes), “It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me” (DeGraw), “She’s Got a Way” (Maines), “She’s Always a Woman” (Groban, accompanied by a string quartet and classical guitar) and “Allentown” (Mellencamp).

Natalie Maines. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

John Mellencamp (right). Photo by Shawn Miller.

Kevin Spacey. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

“Bet you all didn’t know Billy was a protest singer, but he was and is. So, we’re going to prove it right now,” Mellencamp said, launching into a raspy acoustic version of Joel’s song about the blue-collar blues of out-of-work Pennsylvania steelworkers.

By the time Joel released his first album in 1971, the next performer already had been singing professionally for more than two decades. At Constitution Hall, Bennett, dapper as ever at age 88 and in fine voice, earned a standing ovation with his take on Joel’s classic “New York State of Mind.”

LeAnn Rimes. Photo by Shawn Miller.

After Bennett exited, Billington, Sotomayor, House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and Reps. Gregg Harper and Candice Miller entered, escorting Joel to the stage to present him with the Gershwin Prize medal.

“For more than five decades, Billy Joel has inspired new generations of performers, musicians and singer-songwriters,” said Sotomayor, a New Yorker and noted Yankees fan. “Tonight, we recognize Long Island’s favorite son – even if he is a Mets fan – for creating an enduring musical and lyrical legacy for our nation as well as our world.”

Joel propped the medal on his piano, took a seat and performed a brief set (“Movin’ Out,” “Vienna,” “Miami 2017,” “You May be Right”) – prompting Spacey to return to point out a glaring omission.

“I took a poll backstage, and there is a general sense that you’ve left one song out. This song requires a particular instrument,” Spacey said, pulling out a harmonica.

Erin Allen sings a solo during a performance by the Library chorale. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Spacey and Joel duetted on the piano-and-harmonica intro to “Piano Man,” then led the whole cast – and, at times, the audience – through a show-ending sing-along of perhaps Joel’s best-known composition.

In video interview clips shown throughout the evening, Joel discussed his early life, his musical upbringing, the musicians who influenced him and the importance of the Gershwin Prize to him.

“I recognize great songwriting when I hear it. These people who have received the Gershwin award are the great authors of the American Songbook,” Joel said. “I would like to hope that my songs will have that kind of resonance. These songs resonate and will continue to resonate by these great songwriters. It’s a great group to be included in.”

Billy Joel (center) with Boyz II Men, Josh Groban, Gavin DeGraw and Tony Bennett. Photo by Shawn Miller.

The Gershwin Prize concert honoring Billy Joel is scheduled to be broadcast Jan. 2 on PBS.

November 19, 2014

Magna Carta: A Charter for the Ages

(The following is a feature story written by Nathan Dorn, curator of rare books in the Law Library of Congress, for the November/December 2014 issue of the LCM. The issue can be read in its entirety here.)

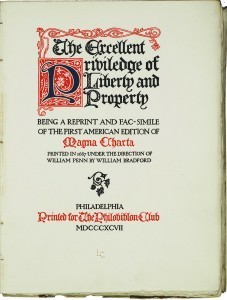

“The Excellent Priviledge of Liberty and Property: Being a Reprint and Facsimile of the First American Edition of Magna Charta,” 1687, Philadelphia, 1897. Law Library of Congress.

After 800 years, the granting of Magna Carta remains a milestone of human history. But why does a feudal charter issued by a medieval king in a distant country still mean so much to us today?

Magna Carta is one of the great symbols of individual liberty and the rule of law. Along with the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, Magna Carta is regarded as a charter of American liberty. Its reputation, however, sometimes conceals its complex history and actual significance.

Magna Carta was originally created as a peace treaty. King John of England in early 1215 faced rebellion in his kingdom from disenchanted barons threatening civil war. When the barons seized the tactical advantage, John had no choice but to accept their demands for reform. The two sides met at Runnymede, a meadow by the Thames River west of London, to discuss terms of agreement. After days of negotiations, on June 15, 1215, John placed his seal on a list of guarantees he promised to uphold in perpetuity.

The document that emerged from John’s conflict with the barons wasn’t an obvious candidate for the reputation it eventually earned. It contains few statements of high principle. Instead, it is a list of practical reforms tailored to the barons’ specific grievances. Many relate to customs and institutions that have not existed for centuries.

Magna Carta doesn’t guarantee individual liberties. Where it promises to safeguard “liberties,” the charter is referring to special immunities the wealthy and powerful could inherit or purchase from the king. The barons mainly hoped to obtain the king’s guarantee to protect their narrow private interests.

Fortunately, that isn’t all they sought. A principal grievance against John was that he disregarded custom-he governed the kingdom in a lawless and erratic way. This disregard was particularly felt in John’s administration of the courts of law. The barons’ charge wasn’t unfair, but there was more to the story. The Plantagenet kings–including John, but especially his father, Henry II– were intimately involved in the development of England’s legal system. Henry II expanded the quality and availability of courts throughout the country, promoting the development of standards for procedure. John carried on this project as well.

This effort had unexpected results for the kings. Both Henry II and John excelled at using the courts and their new instruments of governance to reward friends and punish enemies. But the expanding legal culture created new expectations among the baronage, which now counted on the customs and procedures of the courts to protect their interests.

These expectations, in turn, gave rise to demands for custom as a matter of right–a scenario that could no longer abide the kings’ freewheeling ruling style. This conflict came to a head during John’s reign.

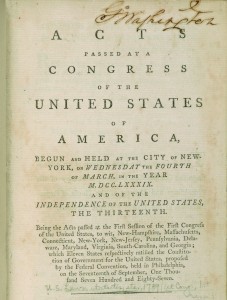

The legacy of Magna Carta continued with the “Acts passed at a Congress of the United States of America,” New York, 1789. Law Library of Congress.

To be sure, John was unpopular for many reasons. To fight foreign wars, he taxed the wealthy at unprecedented levels–and then lost the wars for which he had risked alienating his barons. He was excommunicated by the Church, causing all of England to be placed under interdiction, as a result of an unnecessary argument with Pope Innocent III. John’s last defeat, at the Battle of Bouvines in July 1214, seems to have triggered the rebellion of 1215.

All these factors were important, but it was John’s perceived lawlessness the barons sought above all to address in Magna Carta.

Magna Carta represented, therefore, an argument in favor of rule of law. This can be seen concretely in provisions relating to the operation of the courts. For example, Magna Carta requires that the crown supply neutral witnesses against the accused, that judges be knowledgeable in the law and that fines be assessed according to the severity of the infraction. Justice, it famously guaranteed, should not be sold, delayed or denied.

The most important of Magna Carta’s guarantees has become virtual scripture for the rule of law. It reads: “No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” That single sentence provided protection from prejudgment imprisonment, torture, execution and confiscation of property; it guaranteed a rudimentary form of jury trial and protection from arbitrary court proceedings.

Over time, Magna Carta’s association with the supremacy of law over king grew stronger. Magna Carta was reissued in abridged form many times by John’s successors and later by Parliament.

Beyond its specific guarantees, the charter’s confirmation came to represent a pledge that the king would uphold the rule of law. A series of medieval statutes expanded and amplified some of its core guarantees, so that they applied to all Englishmen and made any law or act of the sovereign that violated the charter’s terms null and void.

In the early 17th century, English jurists, especially Sir Edward Coke, took renewed interest in Magna Carta. Coke, who had been Queen Elizabeth I’s attorney general and King James I’s Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, claimed that Magna Carta placed legal restraints on the king’s prerogative, safeguarding individual liberties from infringement by the monarch. In particular, he interpreted Magna Carta as the legal basis of the writ of habeas corpus, that is, the privilege to petition for a judicial review of the reasons for one’s detention. He saw the charter’s requirement that one may only be imprisoned according to the “law of the land” as a kind of due process protection against being held without charges.

Many ideas that were common to the founders of the American republic–limited government, the consent of the governed, constitutionally guaranteed liberties and judicial review–all owed a debt to the tradition surrounding Magna Carta. Elements of Magna Carta were included in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights, notably the Seventh Amendment right to a trial by jury, Fourth Amendment protections from unlawful search and seizure and the Due Process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Coke may have read into Magna Carta rights not present in the text, but his understanding of the text inspired American law and colonial institutions and ultimately played a major part in the political thought that led to American independence.

The Library of Congress exhibition, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor,” is open through Jan. 19, 2015.

November 17, 2014

David Seymour (CHIM), Photographer of the Spanish Civil War

The following is a guest post by Beverly Brannan, Curator of Photography, Prints and Photographs Division, and first appeared on the Library’s “Picture This” blog.

Photographer David Seymour (CHIM), with three Leica cameras around his neck. Photographer unknown, ca. 1950. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppbd.00599

When I read For Whom the Bell Tolls in my junior year of high school, it was just the most romantic thing I had ever come across, and I fell in love with the thought of fighting for one’s ideals. The Spanish Civil War seemed to epitomize just such a struggle. I was not alone in my idealism. When fighting broke out in 1936, individuals from all over the world rushed to Spain to fight variously for democracy, Fascism, or Communism.

The conflict in Spain also fascinated CHIM, the photographer whose legacy and 103rd birthday we observe on November 20 with a program in the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building (Room 119, 3-4 pm).

Born David Szymin in Poland, he changed his surname to “Seymour” when he emigrated to France. For his pen name, he used CHIM, which is an abbreviation for the French pronunciation of his original surname.

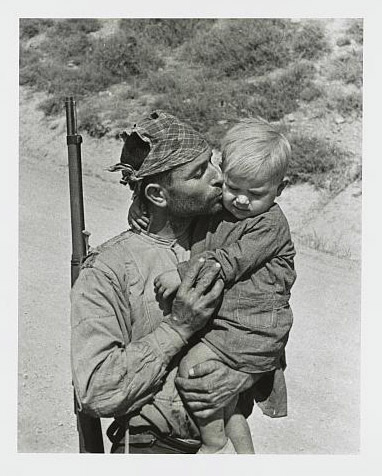

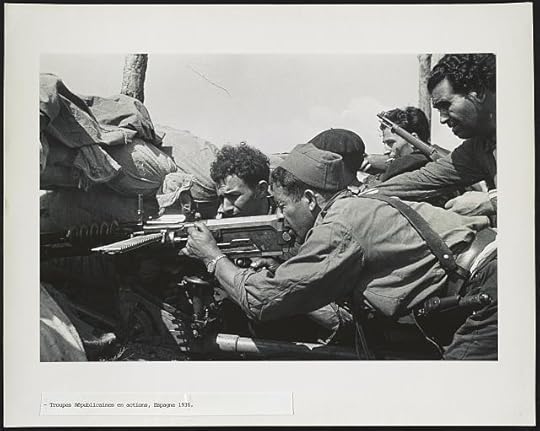

CHIM worked in France as a photojournalist for Regards magazine from 1935 to 1936. From 1936 to 1939, he took many assignments in war-torn Spain. While fellow photographers Taro and Robert Capa focused on combat scenes, CHIM concentrated on the social and cultural aspects of the conflict. His photographs reveal the grim reality of war and represent some of the most iconic images of the conflict.

Soldier kisses his son goodbye, Spain. Photo by CHIM, 1936. © Estate of David Seymour (CHIM)/Magnum, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.37988

Spain Fighting 2: 5 soldiers aiming gun. Photo by CHIM, 1936. © Estate of David Seymour (CHIM)/Magnum, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.38033

After the war, CHIM continued his work as a photojournalist covering international news events. Tragically, he was killed while covering the Suez crisis in 1956.

The Library is grateful for the gift of 112 photographs, including CHIM’s photographs from the Spanish Civil War and other stages of his career donated by his niece, Helen Sarid, and his nephew, Ben Shneiderman. The photographs are an important addition to the Library’s rich documentation of a conflict that attracted international participation and was a precursor to the ideological warfare among fascism, communism, and democracy that affected so many countries in World War II and later.

Learn More:

Take a look at the David Seymour (CHIM) photographs (they show in small size outside Library of Congress buildings because of rights considerations).

View a press release about the recent acquisition of the CHIM photographs and the upcoming commemorative event.

Read an overview of the David Seymour (CHIM) photograph collection in the Prints & Photographs Division.

Explore the relationship between the CHIM photographs and other Library of Congress holdings relating to the Spanish Civil War.

November 14, 2014

Chasing Sadie

My remembrances of Sadie Hawkins Day don’t stem from reading the well-known “Li’l Abner” comic strip by Al Capp, although it was his imagination that created the pseudo-holiday. Growing up in the early 90s, participating was a sort of rite of passage for the girls at school, both junior high and high school. The novelty: girls ask the guys out to a dance. We took it a step further and bought matching plaid shirts for our dates and ourselves to get even more in the spirit.

While this event may not be so relevant today, it’s interesting that a nationwide fad began with a comic strip.

Capp introduced Sadie Hawkins Day on Nov. 15, 1937. In his comic strip, Sadie was the “homeliest gal in all them hills.” Her father, Hekzebiah Hawkins, a prominent resident of their town Dogpatch, was concerned that his daughter would never get married. So he declared Sadie Hawkins Day, bringing all the town’s eligible bachelors together to be chased down by the resident single ladies in a footrace.

The idea really caught on with the public. A Dec. 11, 1939, double-page spread in Life Magazine proclaimed, “On Sadie Hawkins Day, Girls Chase Boys in 201 Colleges” and printed pictures from Texas Wesleyan University. Two years later, Life again reported on a day of “humorous osculation” at the University of North Carolina, along with 500 other colleges, clubs and Army camps across the country.

According to Capp, he received, “tens of thousands of letters from colleges, communities and church groups,” asking when he would declare Sadie Hawkins Day that year so they could make plans accordingly.

In an article Capp wrote for the March 31, 1952, issue of Life, he said, “And how about that Sadie Hawkins Day? It doesn’t happen on any set day in November; it happens on the day I say it happens.”

The comic strip’s main characters, Li’l Abner and Daisy Mae, did the song-and-dance for 15 years before finally getting married, after Daisy Mae caught her prize.

According to Sara Duke, curator in the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, the feature generally began with an announcement that the day was occurring and a few mystical elements about how Li’l Abner was to avoid being trapped. The story line invariably shifted away from Sadie Hawkins Day, only to weave back in a few days before the race.

[image error]

“Midnight madness. Warnin to all Dogpatch bachelors – Sadie Hawkins Day comes on Nov. 6th.” Al Cap, Sept. 25 1943. Prints and Photographs Division. © Capp Enterprises, Inc. Used by permission.

In this 1943 three-panel strip (above), L’il Abner reads the notice about the upcoming Sadie Hawkins Day. And while he predicts that he will be “as far outa her reach as – as – as them stars,” he is horrified when he looks to the sky to see the constellations in the shape of a girl catching her man.

Here’s another strip (below) from the 1943 series, in which it appears that Li’l Abner is trapped.

[image error]

“This is it. Oh *sob* feet! After all we has gone through together … “Al Capp, Nov. 15, 1943.

© Capp Enterprises, Inc. Used by permission.

In the footrace, the men took off first, followed shortly thereafter by the women. Whomever was caught by sundown had to marry. The race started on the announcement day and generally lasted for several days afterward. Li’l Abner always figured out – usually by accident – how to avoid the marriage trap and narrowly escaped – that is until 1952.

“Capp had a wonderful sense of humor and a great ability to tell a story,” Duke said.

The bold cartooning style, use of effective black and Capp’s ability to spin a yarn made “L’il Abner” an award-winning comic strip from 1934 to 1977.

The Library has about 1,000 “Li’l Abner” comic strips in the Art Wood Collection, which have been cataloged but do not yet appear online. There are additional original drawings in the Swann Collection for Caricature and Cartoon and from the George Sturman collection, for which there are some digital images.

The Library’s collections are also rich in American cartoon prints and original drawings, British cartoons and is the repository for the Herblock collection.

November 13, 2014

Pic of the Week: Princess Anne Opens Magna Carta Exhibition

Library curator Nathan Dorn and Princess Anne view the exhibit. Photo by John Harrington.

Last Thursday, the Library of Congress opened a new exhibition, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor,” which marks two special occasions: Magna Carta’s 800th anniversary and the return of the Lincoln Magna Carta to the Library after 75 years, where it was sent for safekeeping during World War II. Guest of honor for the festivities, which also included an evening program following the exhibition’s opening, was Britain’s Princess Anne.

During the opening ceremony, the U.S. Army Herald Trumpets, the Temple Church Choir of London and the Howard University Singers performed, their sounds echoing majestically in the Library’s Great Hall.

“This exhibition really does underscore the importance of great cultural institutions like the Library of Congress and the British Library,” said the princess, who is Queen Elizabeth’s daughter, at the gala. “They have been entrusted with acquiring and preserving the intellectual heritage of our two nations as well as providing access to that heritage.

“This exhibition will very much enrich the public understanding of our heritage, not only by revisiting the major achievements of history but by offering new insights into those achievements in these changing times.”

The Lincoln Magna Carta is one of only four remaining original copies of the document to which King John affixed his seal at Runnymede in 1215. After a six-month public showing in the British Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, the document traveled to Washington, D.C. On Nov. 28, 1939, the British Ambassador to the United States, in an official ceremony, handed Magna Carta over to Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish for safekeeping during World War II. The Library placed the document on exhibition until the U.S. entry into the war, when the Library sent Magna Carta to Fort Knox, Ky. The document returned to England in 1946.

You can read more about the opening day events and see more pictures in these two blog posts from In Custodia Legis, the Law Library of Congress’s blog.

November 10, 2014

Veterans History Project in the News

NBC4 Reporter Chris Lawrence (center) interviews VHP Director Bob Patrick for a Veterans Day-themed news feature.

Photo by Owen Rogers.

As has been the case every year since its inception, the Veterans History Project receives an increased amount of media coverage during the Veterans Day season, both prior to and after the holiday. This year’s coverage included a segment on Washington’s NBC affiliate, NBC4, which aired on Nov. 8. The segment featured VHP Director Bob Patrick explaining the VHP process and a look at a few collections that piqued the reporter’s interest. You may access the story online at www.nbcwashington.com.

Patrick is also featured in a Comcast Newsmaker’s segment, where he discusses VHP’s mission and how to participate. The segment will run on the national XFINITY “On-Demand” and Comcast HD platforms through Nov. 29, 2014. It is also accessible on Comcast Network’s YouTube page.

Today, several radio stations across the country will air interviews of Patrick explaining how to make Veterans Day meaningful and how easy it is to record veterans’ oral histories for the Library of Congress.

Tune in at one of the stations below:

Metro Networks Seattle (Regional)

WAMV (Roanoke)

WPHM (Detroit)

KLTF (Minneapolis)

WBAV (Charlotte)

WYRQ (Little Falls)

WELW (Cleveland)

WDBL (Nashville)

WATD (Boston)

WVNU (Cincinnati)

WQEL (Columbus)

WFAS (New York)

WOCA (Orlando)

WFIN (Toledo)

WSAT (Charlotte)

KDAZ (Albuquerque)

WLKF (Tampa)

KOGA (Denver)

WTER (National)

WRTA (Altoona)

KMA (Omaha)

KWCC (Seattle)

Kansas Information Network (Regional)

Military Life Radio and Navy Wife Radio (National)

CRN- The Chuck Wilder Show- (National)

Making Veterans Day a Meaningful One

(The following is a guest post from Lisa A. Taylor, liaison specialist with the Veterans History Project.)

Amie Pleasant interviews Vietnam Veteran Peter Young. Photo by Christy Chason.

Millions of Americans across the country observe Veterans Day every Nov. 11. Armistice Day, now Veterans Day in the United States, is a commemoration dedicated to all veterans – a way to remember and thank them for their bravery and sacrifice. People choose to mark the day in a variety of ways. However, the Library of Congress Veterans History Project (VHP) has one suggestion that I’d like to pass on to you: make Veterans Day meaningful.

How can you make it meaningful? By volunteering to record the story of the military veteran in your life and submitting it to the Library of Congress, where it will be preserved for generations to come. Participating in this effort will make Veterans Day meaningful, not only for you, but also for the veteran in your life. Go one easy step further and encourage others to do the same by sharing on your social media accounts one or more of VHP’s 16,000 digitized collections that resonate with you.

Established by the U.S. Congress in 2000, VHP’s mandate is to collect, preserve and make accessible the firsthand recollections of America’s wartime veterans. Through a network of volunteers from across the country, VHP has collected more than 95,000 stories and added them to a searchable online database found on VHP’s website.

Participation is easy. All you need is you – the volunteer interviewer, a veteran willing to be interviewed, a recording device and a few forms found in VHP’s instructional field kit. Everyone, from 10th grade students to senior citizens, is welcome to volunteer.

Individuals are not the only ones conducting VHP interviews. Local businesses, libraries, houses of worship, Scout troops, universities, retirement communities and congressional offices participate as well. Here is a look at how some groups are making Veterans Day meaningful this year.

The Veterans History Project is hosting its annual Take Your Veteran to Work Day for all Library of Congress staff.

The National Court Reporters Foundation and the National Court Reporters Association are encouraging their membership to interview the veterans in their lives for VHP.

The VA Center for Minority Veterans launched a new VHP Initiative, which will inspire VHP participation at all 300 locations.

Rep. Donna Edwards (D-Md.) hosted “Vets Count Day of Service” in Fort Washington, Md.

The Flushing Council on Culture and the Arts at Historic Flushing Town Hall in New York will host a workshop with local students and volunteers and begin interviewing local veterans on Veterans Day.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development hosted a combined Veterans Day and employee Health Fair in Washington, D.C.

The Lehigh Valley Veterans History Project in Pennsylvania is encouraging people across the area to interview the veterans in their lives for VHP.

Strong Tower Apostolic Assembly hosted a Veterans Day Brunch and VHP training workshop in Capitol Heights, Md.

In addition to hosting a week-long exhibit, students and volunteers at Carroll College in Montana will read aloud VHP collections, drawing from memoirs and correspondence identified as meaningful to their community.

Blacks in Government hosted a VHP training workshop in Silver Spring, Md.

The Craft in America Center in Los Angeles, Calif., in conjunction with their Service episode and exhibit, will host a VHP workshop for students and volunteers.

DC Public Library is hosting a VHP training workshop at a local branch.

Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) will host a week of “Make It Meaningful” events throughout the district.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will host its annual Salute to Veterans at the Washington, D.C. headquarters.

The Mexican American Community Center in Stockton, Calif., is installing an exhibit centered on community veterans’ photographs, manuscripts and memorabilia, and will host an open house and oral history training workshop.

With all these activities going on, I implore you to do something for Veterans Day, something meaningful that is.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers