Library of Congress's Blog, page 149

March 4, 2015

Here Comes the Sun: Seeing Omens in the Weather at Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inauguration

(The following is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, Civil War and Reconstruction Specialist in the Manuscript Division. To commemorate the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, for a limited time [March 4-7, 2015] the Library of Congress will display both the four-page manuscript copy and the reading copy of the address in the Great Hall of the Thomas Jefferson Building.)

Saturday, March 4, 1865, the day of Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration, “opened rather disagreeably” with a combination of “drenching rain,” drizzling, and “a heavy gale” in the morning. Such were the downpours that The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) even joked “the police were careful to confine all to the sidewalks who could not swim.”

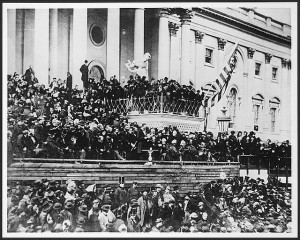

Crowds wade through pools of water and mud to attend Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration, held on the east front of the United States Capitol, March 4, 1865. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Despite the foul weather, thousands of people assembled on the east front of the United States Capitol to witness the first president since Andrew Jackson being inaugurated for a second term of office. Lincoln’s second inauguration also offered the novelty of being the first inauguration held in the shadow of the Capitol’s newly completed cast-iron dome and witnessed by a substantial number of African Americans, some of whom wore blue uniforms reflecting their status as soldiers in the Union army. What a difference four years had made. In 1861, dust – not mud – was the problem, the dome was under construction, and black men were barred from service in the army.

After Senator Andrew Johnson of Tennessee was sworn in as vice president in the Senate chamber about noon, invited guests then moved outside to the East Portico of the Capitol to witness Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration. The president stood behind a small metal table, put on his spectacles and read from a two-columned page of type, which he had cut-and-pasted to guide his reading of his inaugural address. At just over 700 words, Abraham Lincoln’s speech would be the second shortest presidential inaugural address in American history, while also managing to be one of the most profound and memorable. He identified slavery as the cause of the war and looked to God as the arbiter of how long the war would continue. And although the war had not yet ended, Lincoln looked forward to a national reunion by urging “with malice toward none; with charity for all” to achieve “a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.” At the conclusion of Lincoln’s address, Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administered the oath of office, and Abraham Lincoln had once again been inaugurated as president of the United States.

While we tend to remember the stirring words Lincoln spoke in his inaugural address, many who witnessed the event were also struck by the good omens seen in the weather. Accounts vary as to the exact timing of the sun’s appearance, but observers noted that while Lincoln gave his address and took the oath of office, the clouds parted and the sun shone brightly on the ceremony. Lincoln’s secretary John G. Nicolay wrote to his fiancé Therena Bates that “Just at the time when the President appeared on the East portico to be sworn in, the clouds disappeared and the sun shone out beautifully all the rest of the day.” Michael Shiner, an African-American laborer at the Washington Navy Yard recorded in his diary, “Before he came out on the porch to take his [word omitted] the wind blew and it rained with out intermission and as soon as Mr. Lincoln came out the wind ceas[ed] blowing and the rain ceased raining and the Sun came out and it was as clear as it could be….”

Abraham Lincoln reading his Second Inaugural Address. This was the only event at which President Lincoln was photographed while delivering a speech. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Several witnesses to the meteorological change interpreted it as a portent of better days ahead.

Charles Frederick Thomas, superintendent of construction on the Capitol dome, wrote to his family that “on Saturday morning there was a terrible Storm of wind and rain which continued for about an hour and then a few showers until about 11 o’clock. When the President commenced his address the clouds broke away, and by the time he had finished, the sun shone in all its splendor, which I may hope is a good sign for us.” Even Justice Chase, who when secretary of the treasury had not always appreciated Lincoln, wrote to first lady Mary Lincoln that “I most earnestly pray Him, by whose Inspiration it was given, that the beautiful Sunshine which just at the time the oath was taken dispersed the clouds that had previously darkened the sky may prove an auspicious omen of the dispersion of the clouds of war and the restoration of the clear sunlight of prosperous peace under the wise & just administration of him who took it.”

According to Lincoln’s friend, reporter Noah Brooks, even the president had noticed the sun’s appearance, and “went on to say that he was just superstitious enough to consider it a happy omen.” But as Brooks later considered the significance of the sunshine at Lincoln’s second inauguration, he noted that Lincoln, “illumined by the deceptive brilliance of a March sunburst, was already standing in the shadow of death.”

Abraham Lincoln would serve just over a month of his second term. He was assassinated by the actor John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, and died on April 15, 1865.

Lincoln’s words on March 4, 1865, live on, and his Second Inaugural Address is considered one of the finest ever delivered by an American president.

February 23, 2015

The Faces of Engineering

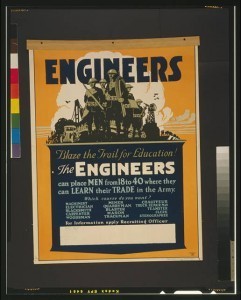

U.S. Army recruiting poster: “Engineers blaze the trail for education!” 1919. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Founded by the National Society of Professional Engineers, Engineers Week (Feb. 22-28, 2015) aims to raise public awareness of the contributions to society of the profession. The celebration is typically held in conjunction with George Washington’s actual birthday (February 22). Washington could be considering one of the nation’s earliest engineers, particularly for his work in surveying.

The Library of Congress is home to the papers of many professional engineers, many with interesting connections.

Last year marked the centennial of the completion of the Panama Canal. Within the Manuscript Division are collections of several men who worked on the project. George W. Goethals was a key figure in the construction and opening of the canal. He was chief engineer in 1907 and helped bring the project to completion ahead of schedule in 1914. He also was appointed first governor of the Panama Canal Zone.

Joseph Cowles Mehaffey started off as a maintenance engineer in the Panama Canal Zone and was later named Governor of the Panama Canal in 1944. He received such honors as the Legion of Merit and Army Distinguished Service Medal for his work.

The Library of Congress has a free, 134-page reference guide to Panama materials in its collections.

William Howard Taft with Col. George Washington Goethals and others, in Panama. Dec. 23, 1910. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The collections also include papers of pioneering aeronautical engineers, including individuals who helped make the Apollo missions possible. C.S. Draper was the founder and director of MIT’s Instrumentation Laboratory (later renamed after him), which made the Apollo moon landings possible through a computer it designed for NASA. According to MIT, the computer was designed to track the spacecraft’s location and velocity and provide steering commands to keep it on the correct path, among other things. Draper himself actually petitioned NASA in 1961 to participate as an astronaut on Apollo’s mission to the moon.

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong took the first footsteps on the moon as part of the Apollo 11 lunar mission. Thomas O. Paine was NASA administrator at the time. According to NASA, during his leadership the first seven Apollo manned missions were flown, in which 20 astronauts orbited the earth, 14 traveled to the Moon and four walked upon its surface.

NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center designs and develops spacecraft, trains astronauts and serves as Mission Control for U.S. space flights. Between 1980-2006, Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Space exploration and the moon have long been a topic of interest, and the Library’s online presentation, “Finding our Place in the Cosmos: From Galileo to Sagan and Beyond,” takes a look at some of that discussion.

The Library’s Science, Technology and Business Division provides research and reference guides on a wide variety of engineering subjects, including Aeronautics/Astronautics, building engineering, civil engineering and on the engineering profession.

Sources: pbs.org, pancanal.com, MIT, NASA

February 20, 2015

An Architectural Marvel 40 Years in the Making

The Washington Monument. April 2, 2007. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The Washington Monument is probably one of the most recognizable structures in all of D.C. At 555 feet, the Egyptian obelisk can be seen from miles away. A particularly picturesque vantage point is looking at the monument through the cherry blossom trees along the tidal basin.

Built to honor President George Washington, the Washington National Monument Society laid the monument’s cornerstone on Independence Day, 1848. However, it would take almost 40 years before the structure would be completed. The monument underwent two phases of construction, one private (1848-1854) and one public (1876-1884).

From the beginning, the monument was beleaguered with troubles, including difficulty with fundraising.

“The original design of the society was to allow every one an opportunity to contribute, and to carry out this idea the amount to be received from any one individual was limited to one dollar,” reported the May 17, 1876, issue of the Clearfield Republican.

The paper also reported that by 1826, only $28,000 had been raised. The monument society decided to lift the restriction and, by 1847, had about $87,000 and the wherewithal to begin construction.

Lithograph from the original design of the Washington Monument by architect Robert Mills. 1846. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The monument also suffered from acts of vandalism, as an issue of the Daily Evening Star reported on March 13, 1854.

“We did not think that a paper published in this country could be found so lost to a sense of every thing that is decent and rights, a to justify the recent outrageous act of vandalism perpetrated in this city by the creatures who destroyed the block of marble sent by the Pope of Rome to the National Washington Monument Association,” began the article.

The paper then reprinted an excerpt from another paper in New York that extolled the destruction of a block of marble sent by the Pope.

Opposition to the Pope’s Stone largely stemmed from the Know-Nothing Party, a group who disapproved of immigrants, especially Catholics, entering the country.

When the obelisk was a little less than one-third its originally designed height, the society lost support and funding, and the monument stood incomplete and untouched some 20 years.

At one point, superintendent of the Washington Monument, William Dougherty, was thrown off the grounds following instructions by the board of managers of the Washington National Monument Society. At that time, the society had been taken over by members of the Know-Nothings. You can read his account in this article from the May 30, 1855, issue of the Evening Star.

Beef Depot Monument. 1862. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The onslaught of the Civil War also contributed to a halt in construction and fundraising. In fact, Union soldiers drilled on monument grounds and used the area to graze cattle and store hay. By the end of the war, the monument and grounds was an eyesore. Mark Twain once referred to it as a “factory chimney with the top broken off.”

Finally, in 1876, the government resumed construction of the monument under the supervision of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Still, disagreements and criticisms about the project continued to be rampant, particularly where the design and foundation’s safety were concerned. The reason the monument looks like it is two different colors is because by the time the project resumed, the stone from the original quarry was no longer available.

When fully constructed, the Washington Monument was the world’s tallest structure. It was formally dedicated on Feb. 21, 1885, to much pomp and circumstance.

The Evening Star reported on the celebration, devoting several pages to coverage of the event and background on the planning and construction of the monument.

Washington Monument as it stood for 25 years. ca. 1860, Photo by Mathew Brady. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

“The Washington National Monument was formally dedicated today with imposing ceremonies. The day was cold and windy, but the sky was clear. Many buildings along the line of the procession were decorated with flags and gay bunting, which gave rich effects of color in the bright sunlight. The program arranged for the ceremonies was faithfully carried out in every detail.”

The monument didn’t officially open to the public until October 1888.

More historical newspaper articles documenting the Washington Monument project can be found through Chronicling America’s topics page on the landmark. The Prints and Photographs Online Catalog also has an abundance of images and architectural designs of the monument.

Sources: National Park Service, “The United States Army Corps of Engineers and the Construction of the Washington Monument,” by Louis Torres

February 11, 2015

A Sense of Purpose: Organizing the Rosa Parks Collection

(The following is a guest post written by Meg McAleer, senior archives specialist in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division.)

Archivists have wonderful jobs. Four colleagues – Kimberly Owens, Tammi Taylor, Tracey Barton and Sherralyn McCoy – and I shared nods of understanding, delight and awe often during the last two months of 2014 as we organized and described the papers of Rosa Parks, the civil rights activist who refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger in Montgomery, Ala., on Dec. 1, 1955, and in the process launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott and a new phase of the civil rights movement. Working through the holiday season, we were fueled in equal parts by excitement and a strong sense of responsibility to get it right for the sake of her legacy and the scholars, young and old, who would be using the collection.

Parks’ recipe for “featherlite” pancakes

The collection contains correspondence, family papers, writings, notes, honors and tributes, financial records, books, and, among other material, an item that entices by its very name – a recipe for “featherlite” pancakes. All told, the manuscript portion of the collection comprises roughly 7,500 items that provide rich insights into Parks’ private life and public activism on behalf of civil rights. An additional 2,500 photographs are preserved in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division. From the perspective of the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, this is a fairly small collection. Our largest collection, the records of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), contains more than 3 million items.The Rosa Parks collection encompasses the most personal of personal papers. The majority of collections we receive consist largely of office files that come to us fairly well organized, having been maintained by office staff. Some collections, however, also contain far more personal papers that are typically stored in homes (as were the Parks papers). There they are stashed in drawers, stuffed in desks and corralled into boxes relegated to attics and basements. Over the years they are taken out, reexamined and reassembled. Idiosyncratic in nature, they are fragmentary rather than comprehensive but very revealing about the private person who also played prominent public roles. Personal papers help us make sense of the public person, understanding their actions, reactions, thoughts and motivations a little more clearly. In one of her autobiographical writings available in the collection, Parks asked herself: “Is it worthwhile to reveal the intimacies of the past life? Would the people be sympathetic or disillusioned when the facts of my life are told? Would they be interested or indifferent?” Hardly making us indifferent, Parks’ collection breathes life into an icon in ways that truly inspire.

Personal papers stored in homes also tend to be poorly organized, as were Parks’. Her papers came to us with a partial item-level inventory prepared by an auction house. The inventory gave us a good sense of what was in the collection, but item-level description is no substitute for an organization that brings like material together in a logical order. Only when logically arranged and sequenced is a collection able to tell a coherent story. It is a lot like a jigsaw puzzle. Individual pieces hint at what is being depicted but only when they are assembled does the picture fully emerge. As an archivist, I know that my arrangement decisions are good ones if the collection’s narrative voice is released. The voice emanating from Parks’ fragmentary writings in the collection is strong, courageous, clear-eyed, grounded in core ethical beliefs and not immune to pain when describing the daily humiliations of racial segregation. That same voice is loving, compassionate and nonjudgmental in the relationships that mattered the most to her.

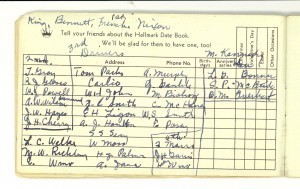

Cover of Parks’ date book

In letters to her husband Raymond Parks in 1957-1958, she shared intimately the heavy toll her protest took on their personal lives. Both Rosa and Raymond Parks lost their jobs in 1956 following her arrest, pushing them over the edge into deep poverty. Another set of records – their income tax returns – reveals how deep and prolonged their descent was.

The collection’s lack of a coherent order actually heightened the thrill of discovery. I found myself opening each container with eager anticipation. Mixed in with material from the 1990s, I found a 1955 date book from the Montgomery Fair department store where Parks worked as an assistant tailor. Opening it, I discovered that Parks had repurposed it as a notebook during the bus boycott in 1956. It brought me closer to those events as I read the names of people who bravely volunteered to drive Montgomery’s African Americans to their jobs.

Inside page of date book

All of us who worked on this collection were deeply inspired by a life lived so completely aligned with principles. To an extent, we felt like the scores of people who wrote to Parks and struggled to express their gratitude for her lifelong crusade for equal rights. For myself, I think I came to admire her most as a writer and for the power of her words. The collection contains bits and scraps of her writings and notes for speeches, created in or around 1956, in which she described what happened that fateful evening of Dec. 1, 1955, and the subsequent unfolding of the bus boycott. In none of her accounts does she portray herself as a lone heroine. Parks worked hard to place her arrest in the broader context of Jim Crow racial segregation and discrimination. She framed her decision to remain seated as one among many incidents of black protest. In other words, what happened on that bus was not a one-off event. “Treading the tight-rope of Jim Crow from birth to death,” she wanted us to understand, always involved, “… a line of some kind – color line hanging noose rope tight rope.” Her words beat at our national conscience.

The collection is now arranged and described in a written guide that lays out its organization and describes its content. Available in the Library of Congress Manuscript Reading Room, the Rosa Parks collection enters a new, dynamic phase of its life, engaging researchers in a dialogue that will leave few indifferent.

This post is part of a short series celebrating Rosa Parks and her collection on temporary loan at the Library of Congress. You can read the first post in the series here.

February 9, 2015

About That Cannon in My Basement —

A few years ago – around 2001, 2002 – I had a cannon in my basement in Rockville, Maryland. You could see it through the front windows, where it was aimed. I wondered if the mailman would report us to Homeland Security.

It wasn’t a real one, but it was incredibly realistic and man-o’war-size (about five feet long). It was made out of scrap wood and styrofoam and was one of the most ingenious set-design pieces I’d seen in several years knocking around in community theater. We put it in our basement because the theater company couldn’t afford storage space, and the only other option in the short term was to put it in a dumpster. It didn’t seem right to get only one show’s worth of use out of such a great piece.

From the Federal Theater Project

Scenic design – the sets, costumes, and lighting — are an essential part of theater, as important as the acting or the singing or the orchestra. They can evoke joy, or controversy. The Library of Congress on Feb. 12 will open an exhibition in its Music Division foyer in the James Madison Building titled “Grand Illusion: The Art of Theatrical Design,” featuring set designs of famous productions and famous designers from its vast theatrical collections, to include opera, ballet, vaudeville and musical theater.

The exhibition includes the work of 21 designers for 28 productions, including Nicholas Roerich, Robert Edmond Jones, Boris Aronson, Oliver Smith, Florence Klotz and Tony Walton. It represents a tiny portion of what the Library offers in this area, and it’s noteworthy that many separate collections here “speak to each other” in that so many luminary figures of the stage — from the musical, production, book or dance cadres — interacted with each other on myriad shows.

Productions highlighted will include the Ballets Russes, the Ziegfield Follies and the musicals “My Fair Lady,” “Grand Hotel,” “Show Boat” and “Chicago”; also included will be holograph music manuscripts from George Gershwin and Frederick Loewe, not to mention letters and scripts by Ira Gershwin, Freddy Wittop and John Kander. The exhibition closes July 25, and then will travel to the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles for display in its Library of Congress Ira Gershwin Gallery from this coming August through February, 2016.

I’m out of theater now, but fondly recall activities onstage and off. I produced two shows for the Washington Savoyards — backstage management, from renting rehearsal space and the set build to directing the stage crew and paying the cast.

Pete, William and Cayetano built sets that were clever, beautiful and–this is important–safe. Pete was responsible for that very lifelike cannon.

The cannon was in the basement for, oh, two years, but finally the day came when we wanted to put our house on the market. So I called William, and asked if he could help me get the cannon over to the storage bay for the Victorian Lyric Opera Company. They thought it might be usable for one of their productions of “HMS Pinafore.” I assumed somebody had a truck.

William and Cayetano showed up with a subcompact Toyota. They pulled the cannon into its two sections, stuffed the muzzle in the back seat and somehow tied the heavy caisson section with ropes onto the roof, and off they went.

There were interesting squash-marks in the carpet, but we got the house sold.

February 6, 2015

Library in the News: January 2015 Edition

More than 112,000 patrons visited the Library of Congress exhibition “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor” during its brief 10-week viewing, which ended Jan. 19.

“Much has been written about Magna Carta’s current visit to America, particularly in relation to the inchoate liberties it birthed. Rightly so,” wrote Kevin R. Kosar for The Weekly Standard. “The Magna Carta’s importance cannot be understated. It is font of the liberties we enjoy today.”

“So the Great Charter is more compelling as a reflection of a broader human quest, and its momentum ever since, despite the autocratic rulers, injustices, and conflicts spread across those eight centuries,” wrote Robin Wright for the New Yorker. “Its spirit, however erratically, has only deepened.”

The Washington Post highlighted the exhibition in its KidsPost section. Reporter Marylou Tousignant explained why the charter was important and the significance of its legacy.

“Magna Carta was the first charter to support the rights of the individual,” she wrote. “And although it was signed in another time and place, it was embraced by the Founding Fathers of the United States more than 550 years later as they wrote the new nation’s Constitution and Bill of Rights.”

Continuing to make news in January was the all-star tribute concert honoring Billy Joel as the recipient of the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. The concert aired on PBS Jan. 2. Covering the concert was Stav Ziv for Newsweek. Ziv spoke to several of the concert participants, including LeAnn Rimes, Gavin DeGraw and Twyla Tharp, in addition to Library officials.

Suzanne Hogan, special assistant to the Librarian of Congress told Ziv that you could see members of the “U.S. Senate tapping their toes and mouthing the words to ‘Piano Man,’ sharing a common moment and common experience,” whatever their political inclinations and personal backgrounds might be, he reported.

Reminding readers that the Library of Congress has a wealth of resources for researchers, Roll Call presented a “refresher” on how to get acquainted with the institution’s collections.

“Whether you are new in town or just haven’t gotten around to perusing the wealth of knowledge maintained by the Library of Congress, now is the time to get schooled in the art of getting one’s proper learn on,” wrote Warran Rojas.

Speaking of collections, the Library has placed more than 400 images from Chilean-born photographer Camilo José Vergara on its website.

“This is the first step toward making more than 10,000 works available to the public,” William Grimes reported for the Artsbeat blog at the New York Times. “The project is open-ended. As Mr. Vergara continues to shoot, his work will be sent to the library and displayed online.

And, lastly, the Law Library of Congress blog, In Custodia Legis, was named one of ABA Journal’s annual “Blawg 100.”

February 5, 2015

Pinteresting African American History

February is African American History Month, an annual celebration that has existed since 1926. This year’s theme, according to the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) is “A Century of Black Life, History and Culture.” This year also marks the centennial of ASALH, which was established in 1915 by Carter G. Woodson, the “Father of Black History.”

The Library is home to comprehensive collections on African American history and culture, particularly robust in the area of civil rights. Currently on exhibit at the Library is “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom.”

To get a glimpse into the breadth of the Library’s collections, make sure to follow the Pinterest board on African American History Month.

Convention of former slaves, Washington, D.C. 1916. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

A few highlights and popular pins include “The Brownie Book,” a monthly children’s magazine edited by W.E.B. Dubois; collections of notable African American figures like Thurgood Marshall and Nannie Helen Burroughs; and striking images such as a photograph of two former slaves, both allegedly over 100 years old, attending an “emancipation reunion” in 1916 Washington, D.C.

In partnership with several institutions, including the Smithsonian and National Archives, the Library has pulled together even more to recognize African-American heritage and achievement. Highlighted are presentations on the artist Hale Woodruff, African American veterans and teacher resources.

Make sure to check out the Library of Congress blogosphere to see what they are posting to commemorate African American History month. Here are a couple of recent postings: In Custodia Legis and Folklife Today.

February 4, 2015

Happy Birthday to Rosa Parks!

(The following is a guest post by Lee Ann Potter, director of Educational Outreach for the Library of Congress.)

Rosa Parks, November 1956. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Born Rosa Louise McCauley on February 4, 1913, in Tuskegee, Ala., the civil rights activist would have been 102 years old today.

It is impossible to imagine how many birthday wishes she received in her 92 years of life, but among the items in the Rosa Parks Collection that recently arrived at the Library of Congress on a 10-year loan from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, there are hundreds of birthday messages–many from school children–sent over a span of nearly 20 years. From 1986 until her passing in 2005, scores of kindergarteners to high school seniors from across the country used the occasion of her birthday to both wish her well and to thank her for the inspirational role she played in the civil rights movement.

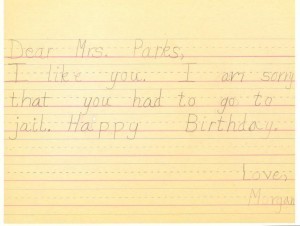

Their notes, drawings, songs, poems and essays reflect varying degrees of knowledge about her refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery, Ala., bus in December 1955. Some mention that it led to a year-long, city-wide boycott ending when the city of Montgomery lifted its law requiring segregation on public buses. Others, like a first grader from Wright Elementary School in Des Moines, Iowa, indicate awareness that she went to jail for her actions. In 2000, Morgan wrote, “Dear Mrs. Parks, I like you. I am sorry that you had to go to jail. Happy Birthday. Love, Morgan.”

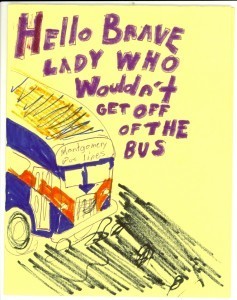

Some of the students point to the bus boycott as the beginning of the modern civil rights movement and to Rosa Parks as its catalyst. Their pride in her is evident. For example, in 2000, a fifth-grader named Ashley from Floyds Knobs Elementary School in Floyds Knobs, Ind., signed a class card to Mrs. Parks with, “Way to fight for your rights! You go girl!” And a 1994 package from seventh-graders in Ohio included dozens of hand drawn cards, including one that on the outside reads “Hey Brave Lady Who Wouldn’t Get Off of the Bus” and on the inside concludes with “Since it’s Your Birthday We’re Making a Fuss.”

Some of the students point to the bus boycott as the beginning of the modern civil rights movement and to Rosa Parks as its catalyst. Their pride in her is evident. For example, in 2000, a fifth-grader named Ashley from Floyds Knobs Elementary School in Floyds Knobs, Ind., signed a class card to Mrs. Parks with, “Way to fight for your rights! You go girl!” And a 1994 package from seventh-graders in Ohio included dozens of hand drawn cards, including one that on the outside reads “Hey Brave Lady Who Wouldn’t Get Off of the Bus” and on the inside concludes with “Since it’s Your Birthday We’re Making a Fuss.”

Quite a few student notes to Mrs. Parks explain that they had either read about her or learned about her actions from their teachers in school. Some suggest a real familiarity and friendliness; a few invite her to visit their school, others tell her to give them a call.

Virtually all of the cards and letters reflect genuine emotions–from appreciation to admiration; from interest to respect. And many describe how her actions encourage them to make the world better. For example, in the very first folder is a note from third-grader ‘Mark’ from Norcross Elementary School in Norcross, Ga., who wished her a happy birthday and announced, “One day I would like to c[h]ange the world like you did.”

Not only do the students tell Mrs. Parks to enjoy her birthday celebration, but a few tell her about their celebration of her special day. In 1990, a hand drawn card and a letter sent by Mrs. Murphy’s first grade class in Indiana describes the chocolate cake that the class had eaten–and a photograph of the students devouring it in Mrs. Parks’ honor is also included.

The bulk of the drawings in the collection are of buses, and most resemble the yellow school bus variety, certainly reflecting student experience. A few are accompanied by thoughtful, original poetry or song lyrics. For her 87th birthday, she received an anonymous card containing the following creatively spelled rhyme, “Happy Birthday to a spchle laddy [special lady]. Roses are red, Vi[o]lets are blue, civil rights are good for you.”

Importantly, among the children’s messages are a few cover letters from their teachers. While they describe class activities and summarize the contents of the students’ cards and letters, many explain what motivated them to introduce students to Rosa Parks, and share their personal sentiments. A hand written letter on flowery stationary, by Mrs. Yellin from New York in 1995, that accompanied class photos and drawings, explained, “My children were touched by your story. . . They also wanted to thank you for your strength and commitment. We all do.”

Yes, we do. Thank you, Mrs. Parks, and Happy Birthday!

February 2, 2015

Alan Lomax’s Legacy

(The following is a story written by Stephen Winick, folklorist and writer-editor in the American Folklife Center, for the January/February 2015 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. The issue can be read in its entirety here.)

Folklorist Alan Lomax at work at his manual typewriter, 1942.

A century after his birth, folklorist Alan Lomax is remembered for his preservation of the nation’s cultural heritage.

Of all the pioneering folklorists and documentarians whose work can be found in the American Folklife Center (AFC) in the Library of Congress, none is as well-known as Alan Lomax (1915-2002), both for the quantity and quality of his collections and for his influence on American culture.

Lomax’s career at the Library began in 1933, when his father, John A. Lomax, became a special consultant to the Library’s Music Division, in charge of the Archive of American Folk Song. Alan took over most of the day-to-day running of the archive, and by 1937 had a position at the Library and the title “assistant-in-charge.” He remained at the Library until 1942, when he left to serve in World War II.

Either alone or with his father, Alan spent his tenure at the Library traveling widely in the United States, carrying an instantaneous disk recorder and often a camera. His signature field trips resulted in some of the earliest documentation of traditional music in Louisiana (including Cajun music) and other parts of the American south (including ballads and fiddle tunes of the Appalachian Mountains and blues from the Mississippi Delta), Michigan and the Midwest (including music of numerous European ethnic communities).

With important collaborators, including his father, his wife Elizabeth, Pete Seeger and colleagues from other institutions (such as Fisk University’s John Wesley Work III), Alan was the first to record Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, McKinley “Muddy Waters” Morganfield, David “Honeyboy” Edwards, Aunt Molly Jackson and an enormous number of other significant traditional musicians. He also recorded many musicians at the Library, including a landmark series of 1938 recordings of Jelly Roll Morton, which yielded nine hours of music and speech. In 2006, “Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax” (Rounder Records) won a Grammy Award for best historical album.

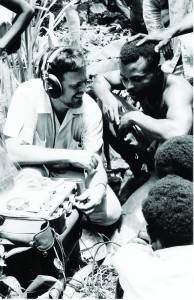

Alan Lomax records the music and language of the people living in La Plaine, Dominica, in 1962.

Antoinette Marchand, Alan Lomax Collection, American Folklife Center.

Lomax did not return to work at the Library after the war, but he did spend the rest of his life collecting and analyzing folk culture for a variety of organizations, including the BBC, PBS Television, Columbia and Atlantic Records, Hunter College in New York, and his own organization, The Association for Cultural Equity. During this time, many of the songs he collected on his Library of Congress field trips became iconic examples of American culture, from “Bonaparte’s Retreat” (which became famous as the hoe-down section of Aaron Copland’s “Rodeo”) to “House of the Rising Sun,” which was recorded by Bob Dylan, the Animals and a host of other musicians.

“Alan was one of those who unlocked the secrets of this kind of music,” Dylan once said. “So if we’ve got anybody to thank, it’s Alan.”

In 2004, the American Folklife Center (AFC) in the Library of Congress acquired the Alan Lomax Collection, which comprises the unparalleled ethnographic documentation collected by the legendary folklorist over a period of more than 60 years.

The collection, which had been housed at Hunter College in New York City, includes more than 5,000 hours of sound recordings, 400,000 feet of motion-picture film, 2,450 videotapes, 2,000 scholarly books and journals, hundreds of photographic prints and negatives, several databases and more than 120 linear feet of manuscript materials.

The acquisition was made possible through an agreement between AFC and the Association for Cultural Equity (ACE) at New York City’s Hunter College and the generosity of Lillian and Jon Lovelace, members of the Madison Council (the Library’s private- sector advisory group). With this acquisition, the Alan Lomax Collection joined the material that he and his father, John, collected during the 1930s and 1940s for the Library’s Archive of American Folk Song, thus bringing the entire collection together at the Library of Congress.

To mark the centennial birthday of the influential folklorist Alan Lomax, the Library’s American Folklife Center is presenting a year-long series of projects, concerts and special events. The events will celebrate the Lomax family’s contributions to the preservation and promotion of traditional music and dance, and highlight the depth and diversity of the Library’s Lomax family collections.

Information about Lomax events at the Library and around the country can be found on the American Folklife Center’s blog, “Folklife Today,” and the Lomax centennial website. You can also read more about the centennial celebration here.

January 31, 2015

A Jefferson Book, Rediscovered in Law Library

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

Anna Bryan holds the book she discovered in the Law Library’s rare-book collections. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

A tiny, handwritten “T” at the bottom of page 113 offered a clue that this book – long part of the Law Library collections – needed a new home: the permanent exhibition of Thomas Jefferson’s library.

Every four months, Anna Bryan and other catalogers in the U.S./Anglo Division’s Rare Materials Section work on an ongoing Law Library project involving American and English law treatises.

While cataloging for that project in August, Bryan picked up an 18th-century volume by John Freeman, Baron Redesdale, “A Treatise on the Pleadings in Suits in the Court of Chancery, by English Bill.”

Examining the leaves, Bryan noticed the markings on page 113: the handwritten “T” next to a printed “I.”

She had seen it before, cataloging books in the “Thomas Jefferson’s Library” exhibition. Jefferson often identified his books by writing his first initial next to the printed “I” signature, which, for printers, also doubled as the letter “J.”

She didn’t, however, expect to find Jefferson’s mark in a Law Library volume.

“I thought, ‘What the heck? I really do need that vacation – now I’m seeing things,’ ” Bryan said.

She wasn’t.

Bryan consulted E. Millicent Sowerby’s annotated bibliography of Jefferson’s library – considered the definitive work – and confirmed her suspicions. She had found one of the original 6,487 volumes Jefferson sold to the Library of Congress in 1815 – books that form the foundation of the modern Library.

Sowerby listed the Redesdale book as No. 1,738 – with a hitch: “The Library of Congress copy, probably Jefferson’s, disappeared sometime ago and cannot be located,” she wrote.

The “disappearance” was, in part, just a reflection of the way Jefferson’s books were viewed in the decades following the purchase of the library.

The Library didn’t gather the volumes in a single collection or even track them as “Jefferson books” for quite some time. The books, after all, were acquired not as historical artifacts but as reference works for everyday use.

“The library was not purchased as a monument to Mr. Jefferson,” Bryan said. “It was purchased for use by Congress in doing its job of legislating.”

Following the invention of the card-catalogue system in the late 19th century, the Library began producing cards for the books in its collections – including cards for Jefferson’s books.

Thomas Jefferson placed his characteristic, handwritten “T” initial at the bottom of page 113. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

The original card for the Redesdale volume, created in May 1919, bears no hint that it once belonged to Jefferson.

That’s not unusual, Bryan said. She estimated that 25 percent of the original cards for books in the Jefferson collection don’t indicate that the volumes once belonged to the third president – again reflecting the perception of his books as a working library.

As decades passed, that view changed. Today, researchers regularly use Jefferson’s books, but their historical importance now is fully recognized, too.

Part of Sowerby’s project in the 1950s was to “rediscover” Jefferson’s books as historical objects. Later, the Library decided to reconstruct Jefferson’s library, gathering all of its Jefferson books in one place and acquiring identical editions of his books destroyed by fire in 1851.

That exhibition opened in 2000, and, now, the Library can add one more volume to it.

“This is just one more example of the great puzzle the project to reconstruct Jefferson’s collections has proved to be,” said Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. “Even though we have been at this for more than 16 years, we are still bumping into unexpected treasures such as Baron Redesdale’s work. And it is certainly no surprise that Anna would be the one to uncover the item. She has evolved into a tremendous sleuth for the project.”

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers