Library of Congress's Blog, page 151

December 25, 2014

Pic of the Week: A Tree Grows … in the Great Hall

The Library of Congress Christmas tree adorns the Great Hall in the Thomas Jefferson Building. Photo by Shawn Miller.

Every year, the Library of Congress decorates the Great Hall with a tall tree for the holidays, replete with lights and ornaments for the enjoyment of visitors.

Zelma Cook of Tryon, N.C., recalls her first Christmas tree and holidays spent with her family and the mill workers of the village in this excerpt from American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940.

“Christmas we always had a big tree. The Company did that for us. My, but it was always a grand affair. We didn’t just gather and sing songs and then maybe get a bag of candy and an orange. We had toys and everything else. There were plays and songs as well, and after that, when we’d all been given our presents, we had hot chocolate and fancy cakes before we went home.”

“I’ll never forget how scared I was when Pa took me to the first Christmas tree there in our little church. That tree just jumped at me as I went in, it was so bright and wonderful; the most beautiful thing I had ever seen in my life.”

How do you celebrate the season? More holiday history from the Library of Congress can be found here. Merry Christmas!

December 24, 2014

Highlighting the Holidays: A Visit From St. Nick

“The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there…” reads the familiar poem most of us know as “The Night Before Christmas.”

However, that title isn’t really correct.

Santa Claus, rosy-cheeked as usual. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, between 1980 and 2006. Prints and Photographs Division.

Clement Moore first penned the poem in 1822, under the title Moore is thought to have composed the tale on Christmas Eve of that year, while traveling home from Greenwich Village, where he had bought a turkey for his family’s Christmas dinner.

Inspired by the plump, bearded Dutchman who took him by sleigh on his errand through the snow-covered streets of New York City, Moore wrote the poem for the amusement of his six children. His vision of St. Nicholas draws upon Dutch-American and Norwegian traditions of a magical, gift-giving figure that appears at Christmas time, as well as the German legend of a visitor who enters homes through chimneys.

A graduate of Columbia, Moore was a scholar of Hebrew and a professor of Oriental and Greek literature at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan. He was said to have been embarrassed by the work, which was made public without his knowledge in December 1823. Moore did not publish it under his name until 1844.

“Twas the night before Christmas.” 1898. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library has other reproductions of Moore’s famous poem in the online presentation An American Time Capsule: Three Centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera.

While not quite an audio-book, the Library has a couple of sound recordings in the National Jukebox of the poem being recited.

Also make sure to follow the Library on Pinterest where you’ll find boards related to the holiday season, including one on Santa Claus.

More historical treasures from the Library of Congress can be found here. Happy Holidays!

* Source: Today in History: Dec. 24

December 22, 2014

Highlighting the Holidays: Home for the Holidays

(The following is a guest post by Monica Mohindra of the Veterans History Project.)

“Home for the holidays”- it’s a sentiment that can cut across lines we might otherwise let divide us. For my dad, it means a longing to be with his family in India for Diwali, a multi-day festival of light that falls each year on dates determined by the Hindu calendar. For a neighbor this year, it meant having her children and grandchildren at home with her for at least one night of Hanukkah.

Home can also be less of a location and more of an idea. For a dear friend, it doesn’t matter where in the world he is for New Year’s, as long as he’s with his loved ones. For me, raised on a holiday culture diet replete with Irving Berlin and Bing Crosby, the idea of home evokes a nostalgic gathering of friends and family, with images of winsome young men in uniform and quaint “make-do” decorations and treats flitting across the projector screen in the back of my mind.

For Alexander Standish, a 45-year-old intelligence officer stationed in Luxemburg near the end of World War II, the significance of Christmas at home was shared with a local family separated by war.

Edith and Yvonne de Muyser, Luxembourg. Alexander Standish Collection, Veterans History Project.

A veteran of World War I, Standish found himself yet again away from his own loved ones during the holiday and sought solace in sharing Christmas festivities with his landlady and her children:

“For weeks the excitement built up in the household — the children became more and more excited, “Mutter” was busy working on dolls’ clothes, dresses, etc. and hiding them in my room where the children would not find them. I decided that Christmas was the same the world over in a family of children.”

While we love the romantic notion of a Christmas-time truce, for Alexander Standish, the war continued unabated through Christmas 1944. Within the Veterans History Project’s “Making it Home” blog series, Standish’s collection has become emblematic for me, illustrating how VHP collections illuminate the commonality of our hopes and dreams for even small moments of peace. I echo his declaration “I decided that Christmas was the same the world over in a family of children.” Despite decades, despite conflict, despite geography, I have decided that the holidays are the same for much of the world: we yearn to be with our loved ones, sharing in a moment of joy and hoping for peace.

Nicholas W. Phillips in front of Christmas tree decorated with beer cans. “Korea Xmas ’52” on reverse. Nicholas W. Phillips Collection, Veterans History Project.

Join us over on Folklife Today to see other ways veterans have made manifest their desires to be home for the holidays and share your own thoughts and memories in the comments. Help us spread these collections that so eloquently voice these universal themes. Please post the images and links wherever you share compelling information-Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Instagram or Pinterest-using the hashtag #VHPatHome. If you’re home with loved ones please consider recording the memories of the veteran in your life.

December 19, 2014

Highlighting the Holidays: The Poinsettia

(The following is a guest post from Francisco Macias of the Law Library of Congress.)

Nativity scene sculpture with poinsettias. Photo by Theodor Horydczak, ca. 1920-1950. Prints and Photographs Division.

Each winter we see poinsettias adorning houses, shopping centers and offices throughout the country. But a little known fact is that the poinsettia is an endemic flora of Mexico. In Spanish it is often called “flor de nochebuena” or simply “nochebuena,” which translates to “holy-night flower.”

According to Mexico City’s Agency for Urban Management, its use as a holiday decoration originates from the early colonial encounter by Franciscan friars, who in turn came to use it to decorate the crèches or nativity scenes. In the Náhuatl language, the flower is called “cuetlaxóchitl,” which means “flower that withers.” It was a symbol of purity, and as such it is more poetically said to be a “mortal flower that withers and perishes like all that is pure.”

According to an entry about “cuetlaxsuchitl” by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún in the “General History of the Things of New Spain“:

“Ay unos arboles en las flor estas que se llama Cuetlaxsuchitl que quando quiebran las ramas destos arboles mana dellas leche on un humor blanco como leche: estos arboles crian unos flores que se llama Cuetlaxsuchitl: las hojas de las quales [sic] son como hojas de cerezo: pero muy coloradas y blandas tiene colorado muy fino pero no tienen ningun olor son hermosas por eso son preciadas.” (pg. 379 – 80; transcribed from the original, as it appears, which serves to explain inconsistencies with modern orthography and omission of diacritics.)

“There are trees that bear these flowers called ‘Cuetlaxsuchitl’ whose branches produce a milk-like substance when they are broken. These trees produce flowers called ‘Cuetlaxsuchitl.‘ The leafs are like those of the cherry tree, but they are very red and pliable. They feature a very fine hue of red, but they have no fragrance. They are indeed beautiful, hence the reason why they are prized.” [Translation with modifications to make it more legible.]

The plant made its way to the United States in the 1820s, thanks to Joel Roberts Poinsett, who was appointed the first U.S. Minister to Mexico (1825-1829) and whose death, on Dec. 12, 1851, resulted in the English re-naming of poinsettia as we know it in today.

More stories on historical holiday-themed items from the Library of Congress can be found here.

December 18, 2014

Highlighting the Holidays: Happy Hanukkah

The Chanucka celebration by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association at the Academy of Music, New York City. 1880. Prints and Photographs Division.

In 2014, December 16 marked the first day of Hanukkah, the Jewish holiday commemorating the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem after its desecration by the forces of Antiochus IV. Also referred to as the Festival of Lights, Hanukkah recalls the event. According to the Talmud, a central text of Rabbinic Judaism, at the re-dedication following the victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucid Empire, there was only enough consecrated olive oil to fuel the eternal flame in the temple for one day. Miraculously, the oil burned for eight days, which was the length of time it took to press, prepare and consecrate fresh olive oil.

“And Judas, and his brethren, and all the church of Israel decreed, that the day of the dedication of the altar should be kept in its season from year to year for eight days, from the five and twentieth day of the month of Casleu, with joy and gladness.” The First Book of the Maccabees, Old Testament, 4:59.

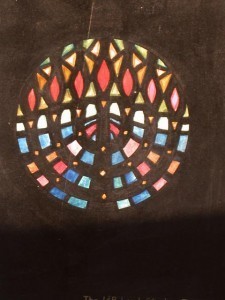

Design drawing for stained glass contemporary tondo window with flames and seven-branch Days-of-Creation menorah. J. & R. Lamb Studios, between 1950-1990. Prints and Photographs Division.

Thus Hanukkah was born to commemorate these miracles. A nightly menorah lighting is at the heart of the festival: in addition to the Shamash, the ninth candle on top, on the first night, a single flame is lit, two on the second and so forth until night eight, when all flames are set alight.

Some typical customs of Hanukkah include eating foods such as latkes (potato pancakes) and sufganiot (doughnuts), all fried in oil; spinning the dreidel, a four-sided spinning top; and exchanging gifts each night.

Hanukkah begins on the 25th day of the Jewish month of Kislev. The Jewish calendar is primarily based on the lunar cycle, and its dates fluctuate with respect to other calendar systems. Thus, the first day of Hanukkah can fall anywhere between November 28 and December 26.

The Hebraic Section in the Library’s African and Middle Eastern Division has long been recognized as one of the world’s foremost centers for the study of Hebrew and Yiddish materials. Established in 1914 as part of the Division of Semitica and Oriental Literature, it grew from Jacob H. Schiff’s 1912 gift of nearly 10,000 books and pamphlets from the private collection of a well-known bibliographer and bookseller Ephraim Deinard. The gift is commemorated with the exhibition, “Words Like Sapphires: 100 Years of Hebraica at the Library of Congress, 1912-2012.”

The Hebraic Section houses works in Hebrew, Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Persian, Judeo-Arabic, Aramaic, Syriac, Coptic and Amharic. Holdings are especially strong in the areas of the Bible and rabbinics, liturgy, responsa, Jewish history and Hebrew language and literature.

American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940 contains both personal recollections and examples of Yiddish folklore. Search the collection for “Jewish” to locate accounts of Jewish culture and traditions such as “A Genzil for the Holidays.”

The collection American Variety Stage: Vaudeville and Popular Entertainment, 1870-1920 features more than 70 unpublished Yiddish play-scripts. “Chanukah Party: A Drama in 4 Acts,” written in 1909 is one such play.

In commemoration of Jewish settlers’ emigration to the New World and their more than 350-year history in America, the Library presents the online exhibition “From Haven to Home,” which features more than 200 treasures of American Judaica from the collections and examines the Jewish experience in the United States through the prisms of “Haven” and “Home.”

In addition, the online exhibition Scrolls From the Dead Sea offers a selection of scrolls from the late Second Temple period.

The Library highlights other holiday stories here.

*Sources: history.org, Today in History

December 17, 2014

The Big Lebowski Abides

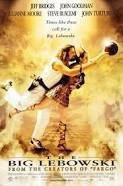

My condition is in fantastic condition today – I’m pleased that “The Big Lebowski” made this year’s list of 25 films selected for placement on the Library of Congress National Film Registry. These movies are judged to have special cultural, historic or aesthetic value and to be worthy of preservation for posterity.

The Dude’s Busby Berkeley bowling dream

Other noteworthy films on this year’s list include “Saving Private Ryan,” “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” “Rio Bravo,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” the 1971 version of “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” Efrain Gutierrez’s 1976 indy picture “Please Don’t Bury Me Alive!” deemed the first Chicano feature film; several reels of footage shot in 1913 that, had work on them been completed, would have been the first feature-length film starring African-American actors; and a silent film from 1919 starring Hollywood’s first Asian star, Japan native Sessue Hayakawa.

If you have not seen the Coen brothers cult classic “Lebowski” yet, let me put it this way: you’re either in for a whole lot of laughs or a heckuva shock. This 1998 movie, which suddenly took off due to internet-related word of mouth after its unimpressive showing in theaters, stars Jeff Bridges as the lesser Lebowski, aka “The Dude”, John Goodman, Julianne Moore, Steve Buscemi and Philip Seymour Hoffman, with wonderful walk-ons by John Turturro, Ben Gazzara and Sam Elliott. Add to that a soundtrack that manages to take in “Driftin’ Along With the Tumblin’ Tumbleweeds,” “What Condition My Condition Was In,” Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” and Creedence.

So, mix yourself another White Russian while I roll out the other highlights of a fine registry list for 2014:

Little Big Man, 1971. This film with Dustin Hoffman and Faye Dunaway flashes back the long, fictitious life of Jack Crabb, a Wild West former scout who spent time among the Cheyenne as a child and moved at the edge of the Indian/cavalary conflicts of the mid-1800s . It was one of the first movies (the genre was referred to as “revisionist Western”) to take up the cause that made Dee Brown’s book “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee” a bestseller after it was published in 1970 – the fact that the history of the Native Americans had never been written from their perspective.

Saving Private Ryan, 1998. This WWII tale won Steven Spielberg an Academy Award, for its unvarnished depiction of the horror of war, with the Allied landing on Omaha Beach as the setting for the story of the effort to spare from death the last surviving son of a U.S. family that already had sacrificed all three of his brothers to the war effort.

Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport, 2000. One of the more touching stories out of WWII chronicled the extensive efforts made by humane adults to get Jewish children out of the occupied nations of Eastern Europe and into safe havens such as England, to save them from being sent to concentration camps. This Academy-Award-winning film chronicles the work; its producer was the daughter of one of the children saved.

House of Wax, 1953. This film is said to have revived Vincent Price’s flagging career. He played a sculptor of wax figures who is badly burned in a fire started by his colleague, who torches the wax museum for the insurance money. The sculptor, masked to hide his hideous burns, begins killing people and dipping their bodies in molten wax to make new figures for his wax museum. This film was an early and successful 3-D flick.

Rosemary’s Baby, 1968. Roman Polanski took Ira Levin’s eerie novel and turned it into a classic of psychological horror. The young and eventually pregnant wife Rosemary becomes convinced her overly solicitous neighbors are actually members of a devil-worshiping coven of witches, in cahoots with her husband to take her child away from her to be sacrificed.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). A film by John Hughes, a director who didn’t forget what it was like to be a teen when he reached adulthood, documents the nervy exploits of the title character (Matthew Broderick), a hooky-playing high-school kid. One highlight, of course, is his teacher (played by former TV game show host and occasional political columnist Ben Stein) calling roll, finding Bueller gone, and ineffectually intoning Bueller’s name, over and over.

Also on the registry list you’ll find:

Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day (1913)

Down Argentine Way (1940)

The Dragon Painter (1919)

Felicia (1965)

The Gang’s All Here (1943)

Luxo Jr. (1986)

Moon Breath Beat (1980)

The Power and the Glory (1933)

Ruggles of Red Gap (1935)

Shoes (1916)

State Fair (1933)

13 Lakes (2004)

Unmasked (1917)

V-E Day + 1 (1945)

The Way of Peace (1947)

You can, and should, nominate films for next year’s National Film Registry: a list of films that are yet-undesignated is here.

Enjoy the movies – and please, don’t roll on Shabbos.

December 15, 2014

Highlighting the Holidays: Window Dressing

“Music” window at Bergdorf Goodman. Photo by Erin Allen.

Over the Thanksgiving holiday, I spent several days in New York City. The holiday season was in full swing, with several holiday markets around town, lights and decorations adorning street posts and buildings and Rockefeller Center nearly completely decked out – the Christmas tree was up but not yet decorated.

One of the things I was most looking forward to was taking in the window displays of the fine department stores, one of the city’s best traditions. For decades, stores like Saks Fifth Avenue, Bloomingdale’s and Lord & Taylor have delighted and amazed passers-by with their whimsical, festive and often over-the-top displays of artistry.

My favorites were the windows at Bergdorf Goodman, Saks and Lord & Taylor. Bergdorf’s windows paid homage to the arts, with mannequins festooned in haute couture surrounded by objects of the specific craft: the “music” window featured a barrage of brass instruments whose shine left spots in your eyes if you stared too long, and the “literature” window showed a collection of portraits of notable writers all done in a red hue.

Saks took a modern look at favorite fairy tales, all done in Art Deco style with Manhattan as a backdrop. Cinderella heads to Saks to buy a pair of designer glass slippers. Rumpelstiltskin spins straw into gold at the City Hall subway station. Little Red Riding Hood encounters the Big Bad Wolf at The Plaza.

Lord & Taylor’s windows were a bit more whimsical, with an enchanted mansion full of mischievous mice, fairies in jars and animated family pet portraits.

According to New York University and Macy’s, R.H. Macy was one of the first to develop the holiday window display. In 1874 its designers created an animated scene of mechanical wind-up toys and dolls.

Christmas toys. Between 1908 and 1917. Prints and Photographs Division.

While many of the retailers have visual presentation staff who develop and direct the visual displays – a process often beginning the moment that year’s windows are dismantled – well-known individuals have been known to be window dressers. This year, director Baz Luhrmann (of “Moulin’ Rouge” fame) developed the windows for Barneys. Other notables have included Andy Warhol, Salvador Dali and Maurice Sendak, according to the New York Times. L. Frank Baum was also a pioneer in the field of commercial window displays.

During the five years preceding the publication of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” Baum earned his living by editing The Show Window, a journal devoted to the art of shop window display. He was also founder and officer of the National Association of Window Trimmers of America and published the first book dedicated to the subject in 1900, “The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors,” which came out the same year as “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.”

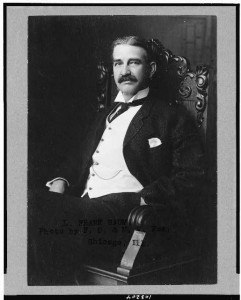

L. Frank Baum. F.S. & M.V. Fox, Chicago, Ill. 1908. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library’s online exhibition, “The Wizard of Oz: An American Fairy Tale” tells the story of Baum’s career as a children’s book author and the development of his Oz books.

The Library’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog has many historical photos of department stores, including images of R.H. Macy and Company during the holidays. This one captures children lined up to meet with Santa. In addition to Macy’s leading the charge in decorative window displays, the store was also the first to introduce an in-store Santa Claus and has been doing so since 1862.

And, if you want to know what it was like to work at Macy’s during the 1930s, you can read Irving Fajans’ account as part of the American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940 collection.

More historical treasures from the Library of Congress can be found here. Happy Holidays!

December 12, 2014

Inquiring Minds: World War II, Through Patton’s Lens

(The following is a story written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

George S. Patton. Prints and Photographs Division.

Imagine, military historian Kevin Hymel writes, if George Washington or Ulysses S. Grant had carried a camera and photographed war as he experienced it. How important would those images be as documents of history?

Gen. George S. Patton, the brilliant but often-troublesome U.S. Army commander of World War II, did just that during his campaigns across North Africa and Europe from 1942 through 1945.

Patton, an amateur photographer who carried an Army-issued Leica camera, took hundreds of photos of the war he lived: ruined towns, dead soldiers, destroyed tanks, civilian refugees, ancient monuments, his palatial headquarters in Sicily (where, he said, all the maids gave him the fascist salute) and, sometimes, soldiers simultaneously taking pictures of Patton as he photographed them.

Those images today reside in the Library of Congress’s Manuscript Division. Patton died following a car accident in Germany just months after the war ended, and in 1964 his family donated his papers – and photo albums – to the Library.

GIs get stuck in the mud in France. George S. Patton Papers. Manuscript Division.

Hymel appeared at the Library on Nov. 18 to discuss the photos and his own book about them, “Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It.” The event was sponsored by the European Division.

The general, Hymel said, mailed the photos home to his wife, Beatrice, to build a historical record of his experiences.

“I’m going to send you photographs and letters so that some future historian can make a less-untrue history of me,” Patton told her.

Beatrice wrote captions and placed his photos into albums along with images of the general taken by others: Patton wading ashore during the Sicily invasion; meeting with Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower; playing with his pet bull terrier, Willie; posing beside a tank in headgear of his own design – a gold football helmet bearing the stars of his rank.

“His photo albums are just like yours and mine,” Hymel said. “They’re photographs that we take and photographs that other people take that we like and put into our albums.”

U.S. Army engineers pose on a bridge they built over the Sauer River into Germany. George S. Patton Papers. Manuscript Division.

The albums also chronicle Patton’s time in limbo following two infamous incidents in the Sicily campaign – he slapped soldiers suffering battle fatigue, drawing the wrath of Eisenhower and Congress. Awaiting a new assignment, Patton restlessly toured forts in Malta, pyramids in Egypt and battlefields and cemeteries in Sicily.

“A year ago, I commanded an entire corps,” he wrote after visiting the 2nd Armored Division cemetery. “Today, I command barely my self-respect.”

Patton claimed one photo saved his life. The general stopped to photograph artillery in action and, seconds later, a shell landed in the path ahead – just where, Patton said, he would have been if he hadn’t stopped to use his camera.

Patton took the near-miss as a sign that God was saving him for greater achievements.

“It’s only a few days later,” Hymel said, “that he gets the call to come to England and command Third Army for the invasion of France and the eventual invasion of Germany.”

December 11, 2014

Curator’s Picks: Magna Carta’s Legal Legacy

(The following is an article in the November/December 2014 issue of LCM, the Library of Congress Magazine. The issue can be read in its entirety here.)

Nathan Dorn, the Law Library’s curator of rare books, highlights five favorite pieces from the Library’s Magna Carta exhibition.

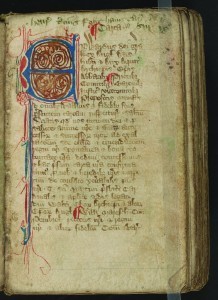

Statutes of England

Statutes of England

“Intricate colored-pen work graces this 14th-century miniature manuscript containing the text of Magna Carta, the Charter of the Forest and the 13th-century statutes of England. This is truly one of the Law Library’s most-treasured items.”

Statuta Nova

Statuta Nova

“Magna Carta’s guarantees originally applied only to people from the top of the social hierarchy. ‘Statuta Nova,’ a medieval book of the statutes of England, contains a 1354 statute that extended those guarantees to ‘a man of any estate whatsoever.’ The first instance of the phrase ‘due process of law’ also appears in this statute.”

Sir Edward Coke on Magna Carta

Sir Edward Coke on Magna Carta

“For more than a century, colonial America learned English law from Sir Edward Coke’s ‘Institutes of the Laws of England.’ Coke claimed in this work that Magna Carta secured inviolable liberties for individuals. This copy belonged to Thomas Jefferson.”

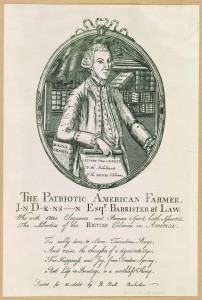

Magna Carta, the Touchstone

Magna Carta, the Touchstone

“John Dickinson, chair of the committee that drafted the Declaration of Rights and Grievances for the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, rests an arm on Magna Carta in this engraving copied from the 1772 edition of ‘An Astronomical Diary.’ Coke’s ‘Institutes’ is placed prominently on his bookshelf above.”

Prints and Photographs Division.

Defying King John

“Heroic outlaw Robin Hood faces down King John in this lithograph advertising the 1895 play ‘Runnymede.’ Magna Carta makes an appearance in the play when an unhappy John finds that Chapter 39 prohibits him from murdering Robin Hood.”

All images from the Law Library of Congress, except where noted.

December 9, 2014

Library in the News: November 2014 Edition

The Library of Congress featured prominently in November news with the opening of a special exhibition and the celebration of a special individual.

On Nov. 6, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor” opened with much fanfare, featuring the 1215 Magna Carta, on loan from Lincoln Cathedral in England and one of only four surviving copies issued in 1215. The exhibition celebrates the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta and also marks the 75th anniversary of Lincoln Cathedral Magna Carta’s first visit to the Library of Congress. In 1939, the Library safeguarded the document during WWII.

“It may look like any other crinkly piece of paper under glass, but Magna Carta is to constitutional law what Louis Armstrong was to the trumpet,” wrote Geoff Edgers of The Washington Post.

The Washington Post Express also featured a story on Magna Carta and the Library’s exhibit.

On hand to open the exhibition was Britain’s Princess Anne. Covering the event was the Associated Press.

“Princess Anne said it is an important exhibition representing the shared values between the United States and the United Kingdom,” AP reported.

“We take so much for granted in terms of our freedoms and our expectations of freedoms and independence, and anniversaries such as this really are reminders of how far we have come in safeguarding our liberties,” she said. “Nearly 800 years ago, Magna Carta gave us our first concept of a society governed by the rule of law — a major step.

The UK newspaper The Telegraph also wrote about the opening.

Special to the Huffington Post, Sir Peter Westmacott, British ambassador to the United States, wrote a blog post on Magna Carta.

“Earlier today, I was honoured to re-enact the 1939 handover, along with the current Marquess of Lothian, whose predecessor the eleventh Marquess was British Ambassador at the time. More importantly, the speech on behalf of my country was delivered by Her Royal Highness Princess Anne–the Queen’s daughter and, in fact, a descendant of King John. Which just goes to show how far we’ve come in a mere 800 years.”

In addition to the exhibit, the Library is presenting a series of lectures and events. Prior to the opening, a discussion of Magna Carta featured Chief Justice Roberts and Lord Igor Judge, a former chief justice of England and Wales.

The Wall Street Journal covered the event.

“The British did not give it over lightly, and I think they did so in a very calculated way,” Chief Justice Roberts said. “They wanted to remind us that this is what they were fighting for, sending a very strong message that you should be, too.”

Later in the month, the Library feted singer-songwriter Billy Joel with an all-star tribute concert as he formally accepted the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song.

“I’m starting to suspect that I have some kind of terminal disease,” Joel told USA Today in an interview before the Library of Congress event. “They keep giving me all these awards, and I’m thinking, ‘Are you trying to tell me something I don’t know?’ I mean, I’m 65 — I’m supposed to be irrelevant. I keep trying to have a dignified exit, and getting pulled back in.”

“Billy Joel has more than a few powerful friends in Washington with a musical legacy powerful enough to draw cheers from both sides of the political aisle Wednesday,” wrote Brett Zongker of the Associated Press.

Frances Stead Sellers of The Washington Post wrote, “[Wowed them] is pretty much what Joel and the musical stars who came to honor him — Boyz II Men, Gavin DeGraw, Michael Feinstein, Leann Rimes, Twyla Tharp, among others — did Wednesday night. This crowd knew his stuff.”

Stories appeared in a variety of other news outlets across the U.S., from Washington to Utah to Louisiana to Michigan, and even in Europe and Canada.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers