Library of Congress's Blog, page 154

October 15, 2014

Celebrating Hispanic Heritage: Cultural Contributions

(The following is a guest post by Tracy North, reference specialist in the Library of Congress Hispanic Division.)

As Hispanic Heritage Month (Sept. 15 – Oct. 15) comes to a close, now is an excellent time to reflect on the many ways in which Hispanic Americans have contributed to our nation’s cultural and political landscape.

Joseph Hernandez, first delegate to Congress from the Florida Territory and brigadier general of the Militia of Florida. Between 1850 and 1857. Prints and Photographs Division.

Hispanic Americans have served in Congress as far back as 1822. The first Hispanic American member of Congress, Joseph Marion Hernández, served as the Territorial Delegate from the Florida Territory as a Whig from 1822-1823. Then, in the second half of the 19th century, the territory of New Mexico was represented by a succession of statesmen, businessmen, veterans and intellectuals. The first Hispanic-American senator, Octaviano Larrazolo, also represented the state of New Mexico (from 1928-1929). In total, eight Hispanic Americans have represented their constituents as members of the United States Senate, including three who serve in the current 113th Congress. On the House side, 100 Hispanic Americans have served – and continue to represent our country – from 12 states and 4 territories including Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, New York and Texas.

While many Members return to their districts to serve their local communities – at the request of current and past U.S. presidents – Hispanic American members of Congress have augmented their political careers by serving the country as cabinet heads and ambassadors after their terms have ended. A publication from the Office of the Historian of the U.S. House of Representatives examines the political trajectory of Hispanic American territorial delegates, resident commissioners and congressmen and senators in our nation’s history.

Hispanic Americans have enlisted in the U.S. military in all conflicts dating back to the Civil War and including both world wars, the Korean War (most notably the 65th Infantry Borinqueneers from Puerto Rico), the Vietnam War, and more recent conflicts in the Persian Gulf. You can learn more about all of America’s veterans by visiting the Veterans History Project, an oral history project that “collects, preserves and makes accessible the personal accounts of American war veterans so that future generations may hear directly from veterans and better understand the realities of war.” A special presentation on Experiencing War: Hispanics in Service shares stories of men and women in all branches of the U.S. military.

Antonio Martinez service picture with division logo. Veterans History Project.

Featured narratives, such as that of Antonio Martinez, animate history. On Christmas Eve 1944, Martinez was one of 2,235 American servicemen aboard a Belgian transport ship, the Leopoldville, on its way from England to France. Five miles from its destination, a torpedo from a German U-boat struck the ship, and it sank within three hours. Martinez helped a man who could not swim. One of the last rescued from the water, Martinez survived, but more than 750 GIs did not. His in-depth account of this tragedy, among the worst in U.S. military history, is an important addition to the public record, as survivors were told at the time not to discuss the episode. It took 50 years before an official monument to those who went down with the ship was erected.

Some featured veterans, such as Leroy Quintana, went on to gain fame after military service. Drafted to serve in Vietnam in 1967, Quintana did at one point consider fleeing across the border into Canada. But his mother had instilled in him respect for military service, and he stayed on. Serving in the 101st Airborne at the height of U.S. involvement, he kept a notebook of his experiences on five-man reconnaissance teams. “There was no reward for people returning from Vietnam,” recalls Quintana, “especially in the Army.” Quintana became a published, award-winning poet who sometimes uses his days in the service as inspiration for his work.

Other stories, such as that of Joseph Medina, give personal perspective to current events. Following in the military tradition of his family dating to the 15th century in Spain and later in Mexico, Medina entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1972. In 2003, Medina was promoted to brigadier general, one of the first Hispanics to hold the rank in the U.S. Marine Corps. More recently, he commanded the Expeditionary Strike Group Three during Operation Iraqi Freedom, during which he was responsible for developing the Iraqi Coastal Defense Force. “If something goes bad in Iraq,” says Medina, “the press focuses on it and everybody sees it. But sometimes they don’t see all the good things that are getting better.”

[image error]

Cuban-owned bakery, “La Borinquena Bakery,” in Paterson, N.J. Photograph by Thomas D. Carroll, 1994. American Folklife Center.

The Library’s collections are also rife with examples of personal stories about Hispanic Americans finding a place in and contributing to the economic development of U.S. society. One rich collection of interviews and documentary photographs depicts the types of jobs held by people of Paterson, N. J., a working-class city a short drive – or train ride – northwest of Manhattan. Within these tremendous oral histories, stories of Puerto Ricans, Dominicans and other Hispanic Americans come to life. In one gem of an audio recording with attorney Beatriz Meza, she recalls the generosity of a mentor who guided her through the rigors of becoming a practicing attorney. Her confidence is admirable: she “feel(s) that being a Latina gives me an advantage” because she is bilingual and possesses multicultural knowledge and skills to work with diverse clients.

In addition to the useful items in our collections such as maps, manuscripts, sound recordings, photographs, posters and of course books detailing the activities of Hispanic Americans, Library staff members have developed helpful tips for researchers, such as the Science Reference Guide that highlights resources on the important topic of Hispanic American Health and the incredibly valuable tools for teachers and educators who are looking for guidance in celebrating the achievements of Hispanic Americans that are described in a past blog post.

The Hispanic Reading Room is available as a starting point for research on Hispanic Americans, Latinos in the U.S. and in Latin America, both historical and current, Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. Patrons and researchers can contact us on the web in English or Spanish.

October 13, 2014

See it Now: Columbus’s Book of Privileges

Columbus’s “Book of Privileges.” 1502. Manuscript Division.

On January 5, 1502, prior to his fourth and final voyage to America, Christopher Columbus gathered several judges and notaries in his home in Seville to authorize the authentic copies of his archival collection of original documents through which Queen Isabella of Castille and her husband, King Ferdinand of Aragon, had granted titles, revenues, powers and privileges to him and his descendants. These 36 documents are popularly called Columbus’s “Book of Privileges.” Four copies of this volume existed in 1502 – three written on vellum and one on paper.

John Herbert, former chief of the Library’s Geography and Maps Division, talks about the book in this video presented in partnership with the History Channel.

{mediaObjectId:'E70D96A4F86D0174E0438C93F0280174',playerSize:'smallStandard'}

The Library’s copy of the “Book of Privileges” – one of the three on vellum – is the only one to contain the Papal Bull Dudum siquidem, the four-page letter that Pope Alexander VI composed on Sept. 26, 1493, which is thought by some scholars to contain the first written reference to a New World.

The papal letter is among the 91 full-size, full-color facsimile pages bound into the Library’s new book, “Christopher Columbus Book of Privileges: The Claiming of a New World,” which also contains the first authorized facsimile of the Library’s copy of the royal charters, writs and grants.

In addition, the pages of the letter have been printed on four loose sheets that are pocketed inside. A translation of the papal bull, which was authenticated in the 1930s, is included.

Levenger Press printed the book in the U.S. to rigorous production standards that include a Smythe-sewn binding and archival-quality paper, both to ensure the book’s longevity. The 184-page hardcover book is available for $89 from the Library of Congress Shop.

The Library debuted “Christopher Columbus Book of Privileges: The Claiming of a New World” at this year’s National Book Festival. A webcast of the presentation is forthcoming.

October 10, 2014

Library Hosts Columbus Day Open House

(The following is a guest post by Library of Congress reference librarian Abby Yochelson.)

Main Reading Room Open House.

Photo by Abby Brack Lewis.

This Monday, the Library of Congress holds its annual Columbus Day Open House in the Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building. Every year, excited tourists and school groups from all over the United States and around the world, families with babies in strollers and eager photographers visit by the thousands. The look on their faces is one of awe, when seeing the soaring dome and magnificent art up close.

Throughout the day, visitors have the opportunity to speak with librarians, view collections from many different parts of the institution and take photos of themselves among the Library’s riches. Tours of the Great Hall and hands-on activities in the Young Readers Center add to the excitement. More information on Monday’s event can be found here.

Open house visitors enjoy taking pictures in the Main Reading Room. Photo by Deanna McCray-James.

Librarians have helped open-house visitors find a record of their book or their father’s or grandmother’s books in the online catalog and delightedly snapped photos of them proudly standing next to the giant screen displaying the evidence that they have a book in the Library of Congress. Teachers and burgeoning family archivists are also regular attendees.

One visitor discovered a great-great uncle’s account of his World War II experience in the Library’s Veterans History Project. Another found the house she grew up in while looking at an 1887 panoramic map of Philadelphia.

Reference librarians on hand at last year’s event recall one young patron asking about material on keeping rats as pets. “My parents said if I write a really persuasive essay, they’ll consider it.”

The Ask a Librarian service is on hand to answer reference questions. Photo by Deanna McCray-James.

However, the open house isn’t the only time visitors can enjoy the Library’s collections and reference services. The Main Reading Room and several other reading rooms are open to researchers six days a week, Monday through Saturday, throughout the year except for government holidays. Anyone 16 years and older with photo identification and curiosity about anything can use the Library of Congress. It’s simple to obtain the Researcher Identification Card and explore a variety of interests, such as family genealogy, the latest astronomy discoveries or diaries of founding fathers to learn their thoughts on the Constitution.

Not everyone can take advantage of coming to the Library in person, so the reference staff works to continuously digitize historical material. The Library not only collects materials from all over the world in all languages and formats, it also makes much of these collections accessible online. Popular collections include the Prints and Photographs Online Catalog, Chronicling America’s newspapers and the National Jukebox. A complete list of the Library’s digital collections can be found here.

In addition, the Library’s knowledgeable librarians can provide reference services virtually through the Ask a Librarian service.

The Library also offers many ways to keep up with news and events, such as exhibition openings (all exhibitions are online too) or new digitized collections, by subscribing to a wide variety of blogs, RSS feeds or email lists.

October 9, 2014

Documenting Dance: The Making of “Appalachian Spring”

(The following is an article written by Raymond White, senior music specialist in the Music Division, for the September-October 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

The Martha Graham Dance Company performs “Appalachian Spring” on the stage of the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium on Oct. 30, 1944. The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation Collection, Music Division.

When “Appalachian Spring” debuted at the Library of Congress on Oct. 30, 1944, the one-act ballet made dance history. Set in rural Pennsylvania during the 19th century, the idyllic story of newlyweds building their first farmhouse evoked a simpler time and place that appealed to a nation at war abroad. Rooted in Americana, the ballet has continued to resonate with audiences during the 70 years since its first performance.

The confluence of several creative forces, each at the top of their game, is a key ingredient to the work’s success. These included choreographer and dancer Martha Graham and her dance partner Erick Hawkins; composer Aaron Copland and artist and set designer Isamu Noguchi. But others played a pivotal role: music patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, who commissioned the work, and the Library’s Music Division chief, Harold Spivacke, who served as impresario.

The story behind the original commission of “Appalachian Spring” began in June 1942 with an idea of Hawkins, a Graham company dancer (and Martha Graham’s future husband). He wrote to Library benefactor Coolidge, suggesting she commission work by the renowned choreographer and dancer Graham.

Mrs. Coolidge, whose 150th birthday will be celebrated with a concert at the Library on Oct. 30, 2014, was a composer and pianist. Although her musical interests were extremely wide-ranging, her greatest musical love was chamber music, and her chief musical passion was the composition and performance of new works in the Library’s concert auditorium, built with her financial support. Since its establishment in 1925, the Coolidge Foundation has commissioned more than 100 works in various musical genres, including four ballets. “Appalachian Spring” is by far the most well- known and most significant of Mrs. Coolidge’s Library commissions.

Graham came to prominence in the 1930s as director and, often, as a principal dancer of her own company. From 1934 on, the woman known as “the mother of modern dance” relied almost entirely on original scores written for her dances (as opposed to creating choreography for pre- existing music). However, she was limited in the choice of composers for her commissions by a perennial shortage of available funds. Thus, when presented with the prospect of a program of new works with scores by composers of the first rank and commissioned by the Coolidge Foundation, Graham wrote to Mrs. Coolidge with excitement: “It makes me feel that American dance has turned a corner, it has come of age.”

Letter from Martha Graham to Aaron Copland, July 22, 1943. The Aaron Copland Collection, Music Division.

The idea took hold, and prompted a flurry of correspondence among Coolidge, Graham and Spivacke. Graham was officially commissioned to create the choreography and Copland to compose one of the scores.

By the early 1940s, Copland was widely regarded as the dean of American composers. He was hailed for works in a variety of genres, many of which are still regularly played today, including his “A Lincoln Portrait,” “El Salón México” and ballets “Billy the Kid” and “Rodeo.” In his letter to Mrs. Coolidge in reply to the offer of the commission, Copland said, “I have been an admirer of Martha Graham’s work for many years and I have more than once hoped that we might collaborate.”

Although he is best remembered as an eminent music librarian and administrator, Spivacke was a key force in bringing “Appalachian Spring” to the Library’s stage. When Mrs. Coolidge expressed concern that her first-choice composers might be unwilling to accept her commissioning fee of $500, Spivacke encouraged her to make the offer regardless, arguing that Graham’s reputation would serve as adequate enticement.

The original schedule was for the premiere performances to be held in 1943, but for a variety of reasons the concert was delayed. It was Spivacke who pressed Graham and the three composers for progress reports, and he ultimately suggested rescheduling the concert for Oct. 30, 1944–Mrs. Coolidge’s 80th birthday.

Mrs. Coolidge left it to Graham to devise the ballet scripts. Graham ultimately supplied the initial story line and scenario for what would become “Appalachian Spring” for Copland. Letters between Graham and Copland reveal the give-and-take between choreographer and composer that resulted in the final course of the ballet.

1946 photograph of Aaron Copland in his studio. Victor Kraft, The Aaron Copland Collection, Music Division.

Its evocation of simple frontier life appealed to Copland and, in the words of Coolidge biographer Cyrilla Barr, “drew from him some of his best expressions of Americana in the form of hymnlike melodies and fiddle tunes, ending appropriately with variations on the Shaker hymn tune ‘Simple Gifts.’”

Copland referred to the work in progress as “Ballet for Martha.” It was Graham who suggested the final title, a phrase from a Hart Crane poem titled “The Dance”:

O Appalachian Spring! I gained the ledge;

Steep, inaccessible smile that eastward bends

And northward reaches in that violet wedge

Of Adirondacks!

Mrs. Coolidge herself had very definite ideas about the new score. She wanted it to be “true chamber music, which is to say for an ensemble of not more than 10 or 12 instruments at the outside” to suit the acoustics of the Coolidge Auditorium as well as its small orchestra pit. In the end, the performance featured a chamber ensemble of 13 wind and string instruments along with a piano, which would allow Graham to tour the work with her company.

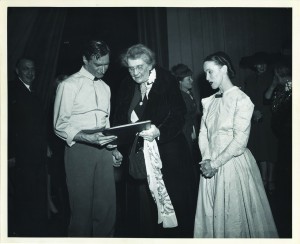

Martha Graham and Erick Hawkins are greeted by Elizabeth Coolidge, center, following the debut performance of “Appalachian Spring.” The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation Collection, Music Division.

At long last, and more than a year later than its originally scheduled premiere, ”Appalachian Spring” was presented for the first time as part of the Library’s Tenth Festival of Chamber Music. Graham danced the role of the bride, Erick Hawkins was the husbandman, Merce Cunningham was the fire-and-brimstone preacher and May O’Donnell played a pioneer woman. The two other works that made up the evening’s program were “Herodiäde” (Mirror Before Me) with a score by Paul Hindemith, and “Jeux de Printemps” (Imagined Wing) with a score by Darius Milhaud.

The performance was well- received. New York Times critic John Martin observed that the tone was “shining and joyous. On its surface it fits obviously into the category of early Americana, but underneath it belongs to a much broader and a dateless category. It is, indeed, a kind of testimony to the simple fineness of the human spirit.”

But the story doesn’t end there. Copland’s score received the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1945. That same year he arranged an orchestral suite of the music for concert performance, and in 1954 he orchestrated a fully symphonic version of the complete score; all three versions of the score remain popular today as concert pieces. “Appalachian Spring” remains a staple in the performing repertoire of the Martha Graham Dance Company.

(The Martha Graham Company in New York City celebrates the 70th anniversary of Graham’s “Appalachian Spring” with a performance of the work on Oct. 30. More information can be found here.)

MORE INFORMATION

Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation Collection

October 7, 2014

Library in the News: September 2014 Edition

On Sept. 10, the Library opened the exhibition “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom.” Covering the opening were outlets including the National Newspapers Publishing Association, the Examiner and regional outlets from New York to Alabama.

“A few things set this exhibition apart from the multitude of this year’s commemorations,” wrote Jazelle Hunt for NNPA. “The Library draws from its exclusive archives of the NAACP, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, James Forman of SNCC, the recently borrowed Rosa Park’ papers, and more.

“But what truly distinguishes the Library of Congress’ exhibition is that it ventures well beyond stock narratives of sit-ins and Freedom Rides.”

“The Library of Congress‘ new exhibit, ‘The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,’ is an absolute must-see for everyone, black or white, male or female, old or young — especially those too young to have lived through this era,” wrote Marsha Dubrow for the Examiner. “The exhibit vividly illuminates that long struggle, and inspires and lights the long struggle ahead.”

One of the civil rights leaders featured in the exhibition is Rosa Parks. In September, the Library announced that her papers would be housed in the institution for the next 10 years, thanks to a loan from the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, with some of the items incorporated into the Library’s exhibition.

USA Today spoke with auctioneer Arlan Ettinger, who helped facilitate the purchase by Buffett of the collection. He said he was gratified that the Library of Congress would be the next stop for Parks’ papers.

“The Buffett Foundation wasn’t acquiring this to put into their vaults, this was an acquisition to do the right thing,” Ettinger said.

Also running stories were ABC, the Associated Press, the Detroit News, the New York Times arts blog and Politico.

Many of the items on display in “The Civil Rights Act of 1964″ exhibition are photographs. They are only a small sampling of the Library’s photographic collections, which cover a wide variety of subjects. Last year, the Library published an e-book featuring some of these. VOA recently talked with the book’s photo editor, Aimee Hess.

“A lot of readers … have said they had no idea that the Library of Congress had images like this. … We wanted people to realize that we have these in our collection, and that these images are for everybody, they’re for the public,” she said. “The bulk of the book are these unknown photographers, and their photographic contributions are just as important and just as interesting and compelling as these household names, so I think it’s really nice that we’re giving them their due.”

Mark Murrmann of Mother Jones also spent time perusing the Library’s photo collections to highlight several images of interest.

Speaking of taking creative license with the Library’s photo collections, artist Kevin Weir creates ghostly gifs using historical black-and-white photos he finds in the institution’s online archive. According to Colossal, a blog that explores art and visual culture, Weir is “deeply drawn to what he calls ‘unknowable places and persons,’ images with little connection to present day that he can use as blank canvas for his weird ideas.”

On Sept. 25, Poet Laureate Charles Wright kicked off the literary season at the Library by presenting his inaugural lecture. Susan Page of USA Today caught up with him to talk about his new job.

When asked, “Why does poetry matter?” he said, “I know why it matters to me. I can’t speak for anyone else. It changed my life. It gave me some valve for the emotional longings that I had as a young man and helped me bring together various independent thoughts that I had. It was very important to me, and I always had a love of language, which is the first thing you have to have if you want to write poems. You’ve got to love the language. And you’ve got to be good at finding new ways of using it.”

Wright also spoke with the Associated Press: “I’m at a stage in my life and career where I don’t need this, but I’m happy to have it if they want me.”

October 3, 2014

Poem Dedicated to Library Published as Children’s Book

(The following is a guest post by Guy Lamolinara, communications officer in the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress.)

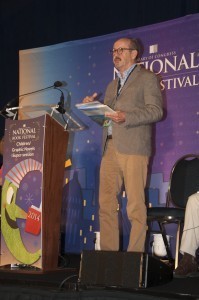

Billy Collins at the 2014 National Book Festival. Photo by Colena Turner.

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins (2001-2003), creator of the Library’s Poetry 180 website, has just published his first illustrated children’s book with artist Karen Romagna. The book features Collins’ poem “Voyage,” which the poet wrote in 2003 and dedicated to John Y. Cole, director of the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress.

That year, Cole celebrated his 25th anniversary as the founding director of the center, and he has recently marked his 50th year of federal service (all but two at the Library).

The poem, presented to Cole in a letterpress edition from the coordinators of the 50 Center for the Book state affiliates, “was a surprise to me,” he said. “The original letterpress edition of 100 copies was printed at the University of Alabama by Steve Miller on handmade paper by Frank Brannon.”

Collins and Romagna discussed “Voyage,” a poem about the pleasures of reading, in the Children’s pavilion at this year’s National Book Festival. (A webcast of the presentation is forthcoming.)

In their presentation, Collins and Romagna discussed their contributions to the 32-page book, released Sept. 1 by Bunker Hill Publishing of Piermont, N.H. (The book is available from the Library’s Sales Shop.)

“The poem’s text and illustrations tell the story of how a young boy searching the beach for treasure comes across a sailboat and pushes out to sea. Magically the boat becomes a book that the boy begins to read, and he finds himself living out its adventure, pirate ship and all, in the fantastic world of words,” said Cole.

“Voyage” is Romagna’s debut as a picture book illustrator. A self-taught artist, she lives and paints in historic Clinton, N.J.

Collins has been called “the most popular poet in America.” While he was Poet Laureate, Collins created the Library’s widely used Poetry 180 website, which offers a poem a day throughout the school year. Collins made another presentation at the 2014 National Book Festival. He also discussed “Aimless Love,” his new collection of poems, in the Poetry & Prose Pavilion.

The Library’s Center for the Book, established by Congress in 1977 to “stimulate public interest in books and reading,” is a national force for reading and literacy promotion. A public-private partnership, it sponsors educational programs that reach readers of all ages through its affiliated state centers, collaborations with nonprofit reading-promotion partners and through the Young Readers Center and the Poetry and Literature Center at the Library of Congress. For more information, visit read.gov.

October 2, 2014

Share Your Photos of Halloween

The American Folklife Center (AFC) at the Library of Congress is inviting Americans participating in holidays at the end of October and early November – Halloween, All Souls Day, All Saints Day, Dia de los Muertos – to photograph hayrides, haunted houses, parades, trick-or-treating and other celebratory and commemorative activities to contribute to a new collection documenting contemporary folklife.

Between Oct. 22 and Nov. 5, AFC invites people to document in photographs how holiday celebrations are experienced by friends, family and community, then post photos to the photo-sharing site Flickr under a creative commons license with the tag #FolklifeHalloween2014.

AFC will explore the stream of photographs shared on Flickr and pick a selection of images to be archived. Of particular interest are images that capture the diversity of practices, people and places that are distinctive in their association with these holidays.

Selected images accessioned by the Library will be shared via the blog Folklife Today in a series of blog posts beginning in November 2014. Depending on the response to this project, AFC may continue using this method to collect documentation of other holidays and other topics.

The Library’s collections are full of documentarians and folklorists including Alan Lomax, Sidney Robertson Cowell and Dorothea Lange, whose work and contributions have inspired this project.

You can read more about this project in a recent blog post from the folklife center, which includes submission guidelines and some example photographs.

September 30, 2014

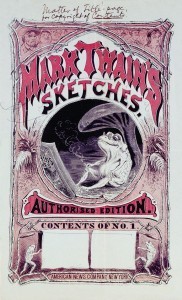

Mark Twain & Copyright

(The following is an article written by Harry Katz in the September-October 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. Katz is a former curator in the Library’s Prints and Photographs Division and author of a new Library publication, “Mark Twain’s America.”)

Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) poses in his classic white suit, 1905. George Edward Perine, Prints and Photographs Division.

Samuel Clemens’ fight for the intellectual property rights to Mark Twain’s works helped protect the nation’s authors at home and abroad.

On May 7, 1874, Samuel L. Clemens–the American author and humorist known as Mark Twain–wrote to Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford, seeking copyright protection for his pamphlet and its cover design. In 1870, the Library of Congress had become the federal repository for commercial and intellectual copyright; authors routinely submitted samples of their work to the Librarian of Congress to document their legal claims.

Accompanying Clemens’ letter was an illustration from “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” the landmark comic sketch that made Twain an overnight literary sensation in 1865 under the title “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog.” Twain was known as “the people’s author” for his wildly popular comic sketches and hugely successful books, ”The Innocents Abroad” (1869), “Roughing It” (1872), and “The Gilded Age” (1873, co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner).

Pamphlet for which Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) sought a copyright from the Library of Congress. Prints and Photographs Division.

It would be several years before his publication of ”The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” but Twain had already discovered the price of success–unauthorized editions of his writings were being published throughout the English- speaking world without due compensation for the author.

From early in his writing career, Twain was victimized by unscrupulous publishers who simply transcribed his published writings into unauthorized editions which were sold without the author’s permission. Pirated editions of his works infuriated Twain, who went to great lengths, traveling to Canada and England, to ensure his copyright and protect his intellectual property. Twain told a reporter, “I always take the trouble to step over in Canada and stand on English soil. Thus secure myself and receive money for my books sold in England.”

Twain became so frustrated by literary piracy that from time to time he considered giving up books to write plays, successfully staging versions of “The Gilded Age,” “Huckleberry Finn,” “The Prince and the Pauper,” “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” and “Pudd’nhead Wilson.”

Twain also became a leading advocate for an international copyright law, which was enacted by Congress in 1891 to extend limited protection to foreign copyright holders from select nations.

In 1900, he appeared before the British House of Lords, and in 1906 made a stunning entrance into a U.S. congressional committee meeting on copyright. As one observer noted of Twain’s unveiling of his trademark white suit, “Nothing could have been more dramatic than the gesture with which he flung off his long loose overcoat, and stood forth in white from his feet to the crown of his silvery head.”

Letter from Samuel Clemens to Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford requesting a copyright for his pamphlet, May 7, 1874. Prints and Photographs Division.

Twain was in favor of perpetual copyright protection. But he supported a bill that would extend the term of copyright from 42 years to the author’s life plus 50 years. The copyright law of 1909–the law’s third general revision– provided for a term of only 28 years, plus a single renewal term of 28 years. The life-plus-50 term was not established in U.S. law until 1978.

At its annual meeting in New York City in 1957, the American Bar Association adopted a special resolution that “recognized the efforts of Mark Twain, who was so greatly responsible for the laws relating to copyrights which have meant so much to all free peoples throughout the world.”

Katz will discuss “Mark Twain’s America” at the Library at noon on Oct. 22 in the Mumford Room, located on the sixth floor of the James Madison Building at 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington, D.C.

“Mark Twain’s America,” a 256-page hardcover book, with 300 color and black-and-white images, is available for $40 in bookstores nationwide and in the Library of Congress Shop, 10 First St. S.E., Washington, D.C., 20540-4985. Credit-card orders are taken at (888) 682-3557 orwww.loc.gov/shop/.

September 25, 2014

Anatomy of the Flute

(The following is a feature on “Technology at the Library” from the September-October 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

Lynn Brostoff of the Preservation Directorate and Carol Lynn Ward- Bamford of the Music Division perform an X-ray fluorescence analysis on a glass

flute from the Library’s collections. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis

The Library of Congress holds the largest collection of flutes in the world, due in great measure to the generosity of Ohio physicist and amateur flutist Dayton C. Miller (1866-1941). Miller donated his collection of more than 1,700 flutes and wind instruments to the Library upon his death.

Housed among Miller’s gold, silver, wood and ivory flutes are 18 flutes made out of glass during the first half of the 19th century by Claude Laurent of Paris. The Library holds nearly half of the approximately 40 glass flutes known to exist worldwide, in institutions like the Metropolitan Museum, the Corning Museum of Glass and the Smithsonian Institution.

Although trained as a clockmaker, Laurent took out a patent for his “crystal” flutes in 1806 and won the silver medal at the Paris Industrial Exposition that year. Laurent’s flutes, with their intricate cut patterns and ornate jeweled keys, are also functional instruments. Some were made for heads of state. One such flute, which was crafted in 1813 and presented to James Madison during his presidency, is permanently on display at the Library of Congress.

The Laurent flutes are the subject of a collaborative research project between the Library’s Music Division and its Preservation Directorate. This cross- disciplinary collaboration is shedding new light on the Madison flute and its sibling glass flutes. The research will allow the Library to care for these rare instruments with the most up-to-date preservation methods, provide a new understanding about the place of Laurent’s flutes in history and enrich the world’s knowledge of 19th-century glass preservation.

The sheer number of Laurent’s flutes in the Dayton C. Miller Collection makes the Library an ideal place for researchers to carry out this work, which was prompted by senior curator of instruments Carol Lynn Ward-Bamford. She observed that some of the flutes were undergoing subtle changes in appearance and enlisted the help of research chemist Lynn Brostoff and conservator Dana Hemmenway. The team is moving forward with an in-depth study that seeks to bring to light the remarkable story behind Laurent’s creation of glass flutes, as well as their current preservation needs. Their tools include a high-powered microscope and the use of X-rays to “see” into the glass and discover its composition.

Close-up of a glass flute undergoing X-ray analysis. Photo by Abby Brack Lewis

The materials analysis carried out thus far by Brostoff has revealed that only two of the 18 flutes are, in fact, made of “crystal,” which is technically leaded glass. The remaining flutes are made of potash glass, so named due to the presence of potassium from the ash used in their manufacture. As the study continues, Library researchers–aided by glass chemists at the Vitreous State Laboratory of The Catholic University of America–will investigate how a new understanding of the materials and manufacturing methods that Laurent used in different flutes may aid in their conservation. Library Junior Fellows Dorie Klein and William Sullivan also are assisting in the Library’s efforts by learning more about Laurent, including a possible family connection to the famous Paris maker of cut crystal, Baccarat.

“The project is amazing,” said Klein, a history and museum studies major at Smith College– and a trained glassblower. “Our goal to determine the structure and significance of these rare flutes is important, both to the Library and to the larger mission of preservation of history.”

September 23, 2014

Remembering the Real Fifties

(The following is a guest post by Tom Wiener of the Library’s Publishing Office and editor of “The Forgotten Fifties: America’s Decade from the Archives of Look Magazine.)

[image error]

“The Forgotten Fifties: America’s Decade from the Archives of Look Magazine” (Skira/Rizzoli and the Library of Congress, 2014).

Look Magazine was a large format, glossy-paged publication that emphasized photography as much as words. Published between 1937 and 1971, it is recalled now as the poor sister of the more heavily financed and successful Life. The magazine was owned by the Cowles family, which also owned newspapers in Des Moines, Iowa, before branching out with Look. After the magazine closed its doors, the family donated the entire Look photo archive to the Library of Congress. It comprises the largest single collection within the Prints and Photographs Division, with an estimated 5 million individual images.

Look was a late bloomer, struggling for respectability in its early years when it published pictures of female movie stars accompanied by simplistic stories. It became known as a barber shop magazine, and Look’s principal owner, Gardner “Mike” Cowles, admitted, “Not until 1950 did Look begin to reach that level of quality for which I had hoped.” In that watershed year, Look began running stories on foreign affairs, on the political scene in Washington and on American communities they dubbed “All American Cities.” 1950 saw the outbreak of war in Korea and the arrival on the American scene of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, a Wisconsin Republican who insisted that the United States government, and in particular the State Department, was riddled with members of the Communist party. Look reported on both of these stories and the anxieties they raised among their readers.

In March 1950, Look ran a story titled “Southern Catholics Fight Race Hatred,” about efforts in Alabama by the church to reach out to black citizens living in an officially segregated society, often in fear for their safety. It was a bold move by the magazine, and reader reaction was strong – both in praise and in condemnation – with many of the latter letters originating from the South. Thus began a decade-long fascination with racial issues in Look’s pages, which reflected the early days of the Civil Rights era.

Look also displayed a fascination with women, but not like in its early days with the plethora of features on starlets. Mike Cowles’ wife, Fleur, became an associate editor at the magazine in 1947, and her hand on the editorial content was evident until the Cowles marriage broke up in 1955. Yes, there were still pieces on female entertainers, from Marilyn Monroe to Lucille Ball, but there were also examinations of the lives of ordinary women, many of them working for a living. In 1950, Look featured a single mother living in New York who worked as an assistant to cartoonist Al Capp, creator of the popular comic strip “Lil Abner”; and on a middle-aged traveling saleslady specializing in lingerie.

Newly published by the Library of Congress, “The Forgotten Fifties: America’s Decade from the Archives of Look Magazine” (Skira/Rizzoli and the Library of Congress, 2014) by James Conaway brings the 1950s to life through images from the collection selected by photo editor Amy Pastan.

In preparing to assemble “The Forgotten Fifties,” Jim, Amy and I were guided by an outline of topics, including the Cold War, the rise of television and rock music, and the shifting dynamics of race and gender. We indexed all the relevant features on these topics, and Amy dove into the Look Collection in search of the most evocative photographs. Jim Conaway wrote his text to the photos in each of the 10 chapters, representing one year of the decade. Our book traces the story of how America evolved from its preoccupations with Communism to the dawn of a different era. The photo that opens the 1950 chapter is from the Korean War, and the last photo in the 1959 chapter is of Jacqueline Kennedy. (The author and editors will be on hand today at the Library to discuss the book. A webcast from the event will be forthcoming.)

The unexpected rewards of dealing with a collection so large was that Amy found many photos that never appeared in the magazine. Either they weren’t used for the article for which they were shot, or the article never ran. For example, in 1954, Look staffer Bob Lerner photographed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson for a feature marking her debut recording for Columbia Records. We found no article corresponding to Lerner’s photos of Jackson at the Columbia microphones, and only after we completed the book did we learn that most of the film Lerner shot for the story was stolen and Look chose not to run an article. A strip of pictures of Mahalia at the microphone appear on page 126 of “The Forgotten Fifties.”

Researching the Look Collection was both exhilarating and exhausting. No book before ours had made such extensive use of the collection, and Amy immediately found that, as a working archive for a publication, Look rarely made prints of its photos. She was faced with poring over contact sheets, slides and color transparencies–all requiring the use of a magnifying loupe. Look wasn’t stingy; on most assignments, their photographers shot dozens, even hundreds of exposures.

Look’s vision of the 50s offers a nuanced view of a decade thought to be prosperous, simple and innocent. Though there are plenty of pictures in “The Forgotten Fifties” of well-groomed kids and smiling suburban housewives, there are also shots of tattoed beatniks and the Little Rock “mob” of angry white people that greeted the nine black teenagers trying to integrate Central High School. Perry Como appears on our pages, as do Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. Doris Day is here, as is “Peyton Place” “bad girl” author Grace Metalious. Look took it all in, and we’re happy to share their view of a decade that’s richer and more complex than is remembered.

The 224-page hardcover book, with 200 color and black-and-white photographs, is available for $45 in bookstores nationwide and in the Library of Congress Shop, 10 First St. S.E., Washington, D.C., 20540-4985. Credit-card orders are taken at (888) 682-3557 or www.loc.gov/shop/ .

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers