Library of Congress's Blog, page 155

September 19, 2014

Mathew Carey (1760-1839), Philadelphia Publisher and Provocateur

(The following is a guest post by Julie Miller, early American specialist in the Manuscript Division.)

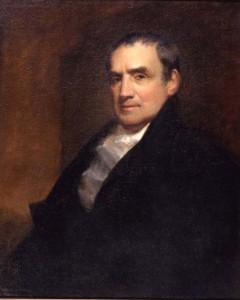

Through the winter and spring of 1825, the Philadelphia publisher Mathew Carey sat for the painter John Neagle. On Feb. 1 he recorded in his diary: “His portrait appears a flattering one. If true, I am a better looking man than I ever supposed.” The Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress recently acquired two manuscript diaries by Carey, including the one containing this entry. Like the painting (now at the Library Company of Philadelphia), the diaries are a portrait of a man who was at once boastful and self-doubting, sociable and cranky, driven and depressed.

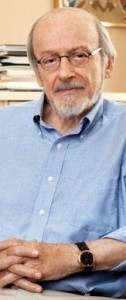

John Neagle (1796-1865).

Portrait of Mathew Carey, 1825.

Oil on canvas.

Library Company of Philadelphia. Gift of Mary Hudson, 1991.

Carey was born in Dublin in 1760, emigrated to the United States in 1784 after several times tangling with the British parliament over his writings in favor of Irish nationalism and Catholic emancipation and settled in Philadelphia. After an early career as a printer, journalist and newspaper publisher, he became one of the most successful book publishers in the U.S. He prospered publishing bibles, schoolbooks, maps and atlases, almanacs and novels. The absence of an international copyright law made it possible for him to republish British books, including the popular novels of Sir Walter Scott, and “Charlotte Temple,” by Susanna Haswell Rowson, which attracted a wide and enthusiastic readership. His American publications included the “Life of Washington,” by Mason Locke “Parson” Weems. In 1801 he organized an annual book fair, to be held alternately in Philadelphia and New York, following the example of the book fairs of Frankfurt and Leipzig. It lasted only a few years, but it fortified Carey’s reputation as a leader in the American book business.

Carey was also an impressively active participant in Philadelphia civic life. He was a member of the American Philosophical Society and the Franklin Institute; a director of the Bank of Pennsylvania and the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal company; and a founder of the Hibernian Society, which aided Irish immigrants. More ephemeral bodies he belonged to included the health committee organized during Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of 1793; a “committee of 24″ that promoted canal-building in the 1820s; and a “friends of Clay” group that supported Henry Clay’s presidential candidacy in 1824.

During the period these diaries cover, Nov. 11, 1821 – Jan. 3, 1823, and Sept. 2, 1824 – Nov. 1, 1825, Carey was easing out of the publishing business and into a new career as an author of essays on political economy and a promoter of what Americans then called “internal improvements.” Like Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay, both of whom he admired, Carey believed that government ought to play an active role in promoting and protecting the American economy. For Carey, this meant federal government protection of American manufacturing through tariffs on foreign imports and the construction of canals in order to speed communication and trade. As early as the 1780s Carey was leading organizations that promoted American manufacturing and the “useful arts.” After the Panic of 1819, an economic collapse whose effects lasted into the early 1820s, he helped found several more, including the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Internal Improvements.

Carey’s economic views are preserved in his writings and in correspondence with friends and political leaders. On Oct. 3, 1822, he wrote retired president James Madison “on the policy that prevails in our intercourse with foreign nations – a policy which renders us hewers of wood and drawers of water to the manufacturing nations of Europe.” Today Carey’s letter is in the Manuscript Division’s James Madison papers. On Nov. 2, 1822, Carey wrote in his diary: “Rec’d a flattering letter from Mr. Madison.” A draft of that reply, dated Oct. 25, 1822, also in the Madison papers, is more flattering than Carey knew. Lengthy and heavily corrected, it is evidence of Madison’s engagement with Carey and his ideas.

Carey’s diaries are also a storehouse of his emotions at a time when the practice of diary-writing was shifting from terse and factual to emotive and soul-searching. An incident in the diary that shows Carey’s emotions from the inside out involves the Marquis de Lafayette. In 1784, Lafayette, in a gesture of life-transforming generosity, gave Carey $400 to start his first American enterprise, a newspaper. In 1824 Lafayette was visiting the U.S. again and Carey wanted to pay him back. In his autobiography, Carey writes that as soon as Lafayette arrived, he sent him a check that Lafayette cashed “only at my earnest insistence” (Autobiography, Letter II, Vol. 5, December, 1833, “New England Magazine,” p.491, “Making of America,” Cornell University). But here is what Carey wrote in his diary on Oct. 2, 1824: “The Marquis de Lafayette’s check paid – so that I was overdrawn about $20. Gloomy and desponding today.”

Carey’s moods appear everywhere in the diaries as the private backdrop to his public life of constant activity and prolific writing. The reputation for irritability he acquired in his lifetime is demonstrated in an entry for Nov. 24, 1824, when he wrote: “Almost determined to cease writing, disgusted with the apathy, worthlessness, & sordid meanness of those with whom I have to deal.” Sometimes his annoyance burst into rage, as on April 4, 1825, when after an incident with his horses he wrote of his coachman: “Outrageously angry with George.”

Especially striking are Carey’s descriptions of his depression and self-doubt. The gloom he experienced when he was unable to repay Lafayette without overdrawing his account is one example. There are more: on Jan. 18, 1822, he wrote: “Rode out to the Robin Hood [a Philadelphia green space] in the gig. Atmosphere hushed. My faculties in good measure benumbed. Fear they are fast decaying. Think I ought to write no more.” He added: “In the evening recovered.” But two days later he was down again: “My mind low spirits. Cannot cheer up my spirits.” He sounds panicked. And on Oct. 13, 1825: “Awoke a prey to the blue devils. Could not regain my spirits all day. Determined to cease writing on public subjects.” That day he went for a ride “to try to raise my spirits – but in vain.” Despite his struggle with the “blue devils,” Carey led an active and productive public life. The diaries show how he struggled to do that.

They also show how he enjoyed himself, or tried to. He went to many parties and gave a few, mingling with Philadelphia’s elite, including Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States and Pennsylvania supreme court justice William Tilghman. He loved the theater, except once when three women in front of him “behaved with boundless indecorum. Talked & giggled & laughed aloud even during the performance. Inexpressibly disgusted at such conduct” (Dec. 18, 1821). A week later he had a better time at St. Augustine’s church, recording this observation about the sermon: “style elegant. Some inconsistency” (Dec. 23, 1821). In 1824 he went to see a painting, “The Resignation of Washington” by the Connecticut-born artist John Trumbull, in Philadelphia as it toured American cities before being installed in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington D.C. “Likeness of Washington most miserable,” he complained on Dec. 4, 1824.

Carey’s deepest pleasure seems to have been reading. Every day he ravenously consumed many pages of books, pamphlets, reports, magazines and newspapers for information, business and pleasure. On Nov. 25, 1821, he “examined a large part of the first album of Macpherson’s annals. Found much matter admirably calculated for my purpose” (David Macpherson, “Annals of Commerce, Manufactures, Fisheries and Navigation,” London, 1805). On Feb. 4, 1822, he “finished reading the Pirate” by Sir Walter Scott, which he was in the process of republishing. On Sept. 20, 1822, he “staid up till 12:30 reading Ennui,” a novel by the Irish writer Maria Edgeworth. On Dec. 26, 1822, he “read 90 pages of the History of an Opium Eater in the carriage & the remainder at night.” This is Thomas de Quincey’s popular “Confessions of an English Opium Eater” (1821). On Sept. 8, 1824, he reports reading the “second number” of Washington Irving’s “Tales of a Traveler,” which was “much better than the first.”

The diaries show Carey at work as a publisher. His entry for June 17, 1822: “Rose at 5. Wrote, corrected & read proofs” is typical, and he frequently reports getting bank loans for his son Henry Charles Carey and son-in-law Isaac Lea (husband of his daughter Frances and a scientist), who joined him in the business and then took it over when he retired. As he eased out of publishing, they show him writing on the subjects that possessed him during these years. Starting in 1822 and continuing through and beyond the period the diaries cover, Carey published more than 60 essays on economic subjects for which he used the pseudonym “Hamilton.” He notes the composition and publication of these in his diary entries, as on Oct. 28, 1822, when he “completed Hamilton No. 5 & sent it to the press.” His working methods are revealed in this entry showing how he spent the evening of Jan. 9, 1825: “After 7 began an essay on Canals, which I finished before one, although it required considerable research in Niles Register. To bed at one.” The diaries may help identify essays Carey published anonymously. For example, his entry for April 22, 1822, reveals that he was the author of an address signed “a Pennsylvanian.”

Carey’s life was packed with incident. Even during the four years these diaries cover, there is more than can fit in a blog post. Had blogs existed during Carey’s lifetime (imagine quills and candlelight mixed with digital clicks and flashes), he would certainly have been a blogger. He would have described the dinners he attended during Lafayette’s visits to Philadelphia in 1824 and 1825, the observations of Philadelphia and its hinterlands he made during his daily carriage rides, and much more. Carey had more to say and a lot more can be said about him with the help of these two diaries, now at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

September 17, 2014

We the People

Today we celebrate the 227th anniversary of the signing of the United States Constitution in Philadelphia, Penn., which was ratified at the Constitutional Convention on Sept. 17, 1787.

[image error]

“The Constitution,” one of six new Student Discovery Sets for the iPad, now available from the Library of Congress.

The Library recently released a series of interactive eBooks for tablets, including a set on the Constitution, which can be downloaded for free on iBooks. The new Library of Congress Student Discovery Sets bring together historical artifacts and one-of-a-kind primary source documents and objects on a wide range of topics, from history to science to literature. Interactive tools let students zoom in for close examination, draw to highlight interesting details and make notes about what they discover.

The set on the Constitution follows many of the drafts and debates that brought the historical document into being. With a swipe of a finger, students can scrutinize George Washington’s on the Constitution, read newspaper articles about the document or use prompts to help analyze such things as maps and letters.

[image error]

Detail with drawing palette from “The Constitution.”

Other sets available cover the Symbols of the United States, Immigration, the Dust Bowl, the Harlem Renaissance and Understanding the Cosmos.

The sets are designed for students, providing easy access to open-ended exploration. A Teacher’s Guide for each set, with background information, teaching ideas` and additional resources, can be found on the Library’s website for teachers.

The Library of Congress has excellent Constitution Day resources, including this page that pulls together a variety of materials from across the institution’s collections.

September 15, 2014

Celebrating Hispanic Heritage: Feliz Cumpleaños, Hispanic Division

(Today is the beginning of Hispanic Heritage Month, which is celebrated annually Sept. 15-Oct. 15. This year, the Library’s Hispanic Division marks its 75th anniversary. The following is an article from the July-August 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine .)

[image error]

“Entry into the Forest” is one of four murals by Brazilian painter Cândido Portinari in the Hispanic Reading Room. Carol Highsmith

Dating back to the middle ages, the Library’s Hispanic world collections are the largest in the world.

An original 1605 copy of Miguel de Cervantes’ “Don Qixote.” A 16th-century Native American legal document protesting Spanish colonialism. Films of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders after the Spanish American War in 1898.

These are just a few of the Library’s Hispanic treasures. Comprising nearly 14 million items in various formats, the Library’s Iberian, Latin American and Caribbean collections are the largest and most complete in the world.

The point of entry for these collections is the Library’s Hispanic Reading Room, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year. The reading room opened its doors in the Thomas Jefferson Building on Oct. 12, 1939, Columbus Day. The Hispanic Division was established three months earlier with an endowment from Archer M. Huntington (founder of the Hispanic Society of America), a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and a congressional appropriation.

[image error]

The Library holds this 1605 first edition of Miguel de Cervantes’ classic “Don Quixote.” Amanda Reynolds

Huntington began donating funds to build the Library’s Hispanic collection in the 1920s. But the Library’s collections from the broad Hispanic world–which date to the Middle Ages–began more than a century earlier. Thomas Jefferson’s personal library, which the Library of Congress purchased in 1815, contained about 200 books about the Hispanic world. Jefferson believed in the basic unity of the Americas–North and South. In 1820 he declared, “I should rejoice to see the fleets of Brazil and the United States riding together as brethren of the same family and pursuing the same objects.”

The Hispanic Division’s first chief, Lewis Hanke, was the founding editor of the “Handbook of Latin American Studies.” Considered to be the father of the field of Latin American Studies in the United States, Hanke became the first Latin Americanist to be elected president of the American Historical Association. In remembrance of their father, Hanke’s children donated funds to the Hispanic Division to offer online access to the Handbook.

In addition to books, journals and manuscripts, the Hispanic Division holds an original collection of sound recordings. The division has been recording selected readings by poets and writers for more than 70 years. Today the “Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape” holds nearly 700 recordings from more than 32 countries in some 10 languages. Among the authors are nine Nobel laureates, including Gabriela Mistral, Octavio Paz and Gabriel García Márquez. Cuban-American poet Richard Blanco, who read his poem “One Today” at Barack Obama’s second presidential inauguration, was recently recorded and added to the collection. Using cutting-edge technology at its Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation, the Library is transferring the retrospective recordings from magnetic tape reels to a digital format.

Hispanic Division Chief Georgette Dorn contributed to this story.

September 12, 2014

Conservation Corner: A Persian Manuscript

(The following is a guest post written by Yasmeen Khan, senior book conservator in the Conservation Division.)

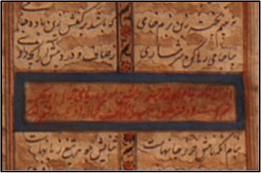

Opening page showing tears and grime. The opening illumination on the right and the calligraphy are of poorer quality than the rest of the text. A chapter heading can be seen in the gold cartouche on the left.

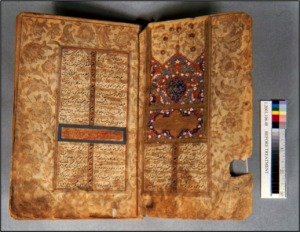

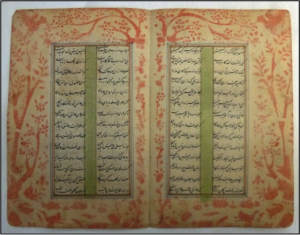

Conservation staff recently treated a rare Persian manuscript in preparation for display in the Library of Congress exhibition, “A Thousand Years of the Persian Book.” The bound 103-leaf manuscript, dated 1583 and attributed to Central Asia, forms the fifth tale in a seven-part work of poetry by Nasiruddin Jami (d. 1492) called the “Haft Aurang” (“Seven Thrones”). Titled “Yusuf wa Zulaykha,” the story follows Joseph and Potiphar’s wife based on the tale told in the holy Qurʼān.

The Library’s 1583 copy came to the Book Conservation Section with both covers missing and many tears and losses in the paper of the first and last few leaves of the manuscript. On the other hand, the calligraphy of Jami’s poetry was in a beautiful nasta’liq hand – a predominant style of Persian calligraphy in the 15th and 16th centuries – and the fine polished leaves of the book were painted in various styles and colors.

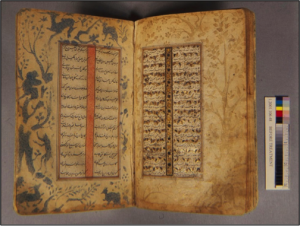

An opening from the text showing two types of decoration: the sinuous stenciled decoration on the left, with a stenciled inner column; and gold painted decoration on the right which consists of a stenciled layer finished with a gold painted lines.

While documenting the manuscript, however, the inconsistencies of the decorative program immediately caught the eye.

Stencils of flora and fauna were used to decorate the margins with watercolors, while the text was framed with multiple lines of black, red, gold and blue. A blank column dividing the text area into two was also spattered with color using the same technique as the stenciled margins. Chapter headings were written in white, red and blue inks, respectively, on gold cartouches set into the text area. Occasional pages were more richly decorated with gold within the text and in the margins.

Upon further inspection, the first six leaves of the manuscript were of a much lower quality than the rest: the calligraphy was bad, the ink used was less opaque, the details of the multicolored illumination above the opening lines were badly executed, and subsequent leaves used large stencils that seemed more akin to Matisse’s collages than the delicate forms in the rest of the book. The sinuous and delicate stenciled margin decorations in the greater part of the manuscript were found in two configurations: with either the same color on both pages of an opening or with a different color on each page.

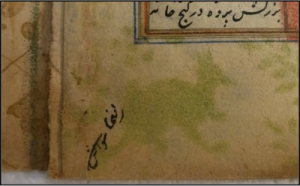

The difference in the crispness of the ink and the calligraphy on the cartouche is clear. In addition, the blue used to outline the cartouche show that they are lapis lazuli of different quality.

Disassembling the manuscript revealed more design inconsistences: some opening pages were decorated with the same stencil and color, others had different stenciled designs or colors and old catchwords under the margin paint had been crossed out over the paint and new catchwords had been inscribed. In addition, paper stubs along the spine showed that someone had removed a few leaves. It was clear that the book was not in its original order.

A crossed out catchword with the new catchword written next to it that show the new order of the pages after some pages had been removed. The blurred blue line by the text is evidence that the green paint from the stenciled design was applied later.

Understanding the original order of the pages was essential to gaining insight into the decorative inconsistency, the damage visible and the use that the manuscript had received. The Library’s manuscript was compared to another edition of “Yusuf and Zulaykha” printed in Bombay, India in 1884. It was discovered that approximately 50 leaves constituting 1,130 lines of rhyming couplets had been removed, mainly from the second half of the manuscript. The comparison also revealed that the graphite Persian numbering of the pages in the last half of the book was done in order to maintain the same color in the margin decorations for facing pages of the manuscript and not on maintaining the integrity of the text. For example, the leaf I had numbered 101 based on its order in the bound manuscript carried the earlier graphite Persian page number 83. After disassembly and review of the text, the page was found to follow the leaf I had numbered 89. There were many such instances that illustrate how complicated and puzzling a process this was.

Two designs for the colored stencils are found in the manuscript: the animal design shown above and the one shown here. Birds predominate in this image, though fish are shown in the rocky pond along the lower margin, as well as ducks and squirrels.

Finally, after putting the manuscript back into the order of the text and looking at the evidence of the stenciled decoration, catchwords and Persian page numbers, a possible history of the use of the manuscript began to take shape.

The manuscript was written and illuminated in a delicate style (a few of those pages are still extant), and it may have been bound. Over the course of its history it was likely rebound several times and edited and redesigned to include stenciling, trimming, adding and removal of the leaves. New catchwords were written along the lower inner margin of the leaves, the pages were numbered in graphite and the leaves were put in order based on the color of the opening leaves.

[image error]

All the extant sections or gatherings of the “Yusuf wa Zulaykha” laid to collate the text.

Though more scholarly work needs to be done on the manuscript in terms of its relationship to other copies of 16th century “Yusuf and Zulaykha” manuscripts from the Persian world, I had enough information to treat and prepare the leaves of the manuscript in their correct order for display in the exhibition on “A Thousand Years of the Persian Book.” In late September when the show ends, the leaves of the manuscript will be rebound with goatskin leather in a Persian-style binding appropriate to the time when it was written.

“A Thousand Years of the Persian Book” closes Sept. 20 in the South Gallery of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building. The exhibition is available online.

September 10, 2014

Songs of a Movement

Music is a powerful tool. It can create an emotional response, a feeling, a certain attitude. Music can unite people, and give a voice when simple words fail. During the Civil Rights Movement, music played a vital role. Freedom songs drew from spirituals, gospel, rhythm and blues, football chants, blues and calypso and were sung by protesters, activists, civil rights leaders and music legends to spread the message of the movement.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., called these songs ”the soul of the movement” in his 1964 book “Why We Can’t Wait.” Civil rights activists ”sing the freedom songs today for the same reason the slaves sang them, because we too are in bondage and the songs add hope to our determination that ‘We shall overcome, Black and white together, We shall overcome someday.”’

In the new Library of Congress exhibition, “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,” which opens today, 25 songs from the era are highlighted.

Making up a large group of music in the exhibition is a selection of songs from Smithsonian Folkway’s “Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: Black American Freedom Songs 1960-1966.” Many of the songs were recorded live during mass meetings. Several of the songs feature the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Freedom Singers, a performance group arm of one of the key organizations in the civil rights movement. The singers performed throughout the country to raise money and awareness for SNCC.

Whether sung in churches or in jails, such freedom songs as “Oh Freedom (Over Me)” and “This Little Light of Mine” helped to shape the movement and sustain it in moments of crisis. Most freedom songs were common hymns or spirituals familiar to the southern black community; the lyrics were often modified to reflect the political aims of the civil rights movement rather than the spiritual aims of a congregation. The songs not only reflected the views and values of the movement’s participants but also, in the case of the Freedom Singers, helped to share them with a national audience. (Hatfield, Edward A. “Freedom Singers.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 11 July 2014. Web. 08 September 2014.)

Considered the unofficial anthem for the movement, “We Shall Overcome,” popularized by folk singer Pete Seeger, has its roots in African-American hymns from the early 20th century, and was first used as a protest song in 1945, when striking tobacco workers in Charleston, S.C., sang it on their picket line. A few years later, activists in the civil rights movement discovered the song and quickly made use of it during protests, marches and sit-ins. You can read more about the song in this blog post from the American Folklife Center.

Often referred to as the African American National Anthem, “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” was a poem written by James Weldon Johnson and set to music by his brother John for a special celebration of President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday on Feb. 12, 1900, in Jacksonville, Fla. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) later adopted the work as its official song.

Featured on a listening station is Louis Armstrong’s “What Did I Do To Be So Black and Blue?” Known as the first American popular song of racial protest, the jazz standard was written in 1929 by African American songwriters Thomas “Fatts” Waller and Andy Razaf for an all-black-cast Broadway musical revue. Originally conceived as a romantic lament, Armstrong transformed it into a protest song against racial discrimination. The song inspired Ralph Ellison to write in his book “Invisible Man” that Armstrong “made poetry out of being invisible.”

“The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom” is made possible by a generous grant from Newman’s Own Foundation and with additional support from HISTORY®.

September 8, 2014

Library in the News: August 2014 Edition

In August, the Library of Congress was busy with exhibitions and expositions, opening “American Ballet Theatre: Touring the Globe for 75 Years” on Aug. 14 and hosting the 14th annual National Book Festival on Aug. 30.

“At the company’s heart was ballet theater, a physical way of creating a new world onstage,” wrote Sarah Kaufman for The Washington Post. “If the scope of that effort has narrowed in recent years, with a reliance on old favorites and warhorses, at least the evidence of its flourishing is preserved under glass.”

The Washington Post Express also ran a photo essay on two images on display in the exhibition.

The opening of the American Ballet Theatre (ABT) exhibition also celebrated the Library’s acquisition of the dance company’s archives.

“[The Library of Congress] seemed like a natural fit, as we are a national company,” said Rachel Moore, ABT’s chief executive, who spoke with Roslyn Sulcas of the New York Times.

The National Book Festival received much press preceding the event, including advance announcements in DCist, Roll Call, Fine Books Blog and by Fox 5.

Stories on festival coverage continue to trickle in, but the Washington Post reported immediately following the event. Because the festival was moved to a new, indoor venue this year, its change in location received media attention.

“As thousands upon thousands of readers of all ages filled the cavernous conference halls at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center — and lined up to buy books signed by their favorite authors — organizers let out a collective sigh,” wrote Post reporter Brigid Schulte. “It worked.”

While the Library’s Civil War exhibition closed earlier this year, its resources continue to make news. One of the highlights on display included the diary of LeRoy Gresham, an invalid teenager who chronicled the war. The Library in August posted a letter online by his mother written following his death, along with LeRoy’s full seven-volume, five-year journal.

“The diary, which the Library thinks has never been published, is a fascinating look at the war through the eyes of a precocious Southern youngster who was largely housebound by illness,” wrote Michael Ruane for The Washington Post. ”Mary Gresham’s letter, which the Library thinks has never before appeared in a public forum, is a voice from outside the journal. She is the offstage presence but has been watching her son’s deteriorating health and approaching death.”

In other news on the Library’s Civil War resources, the institution recently acquired a new 150-year old tintype to ad to its vast collection of wartime images. The photograph, donated by longtime Library supporter Tom Liljenquist, features a young Confederate soldier with his servant, who is also dressed for battle.

“The photograph is a tiny window into the past, but it also presents modern Americans with an enduring image of the role of race in the United States,” wrote Ruane for the Post. “It portrays two men who are bound, willingly or unwillingly, in a common story.”

And, perhaps because of its exhibitions and collections, the Library of Congress was named a 2014 Travelers’ Choice, Top 25 Landmarks in the United States by TripAdvisor.

Lastly, the Library’s preservation work continues to make headlines. Recently, the institution began efforts to study the longevity of compact discs.

Preservationists are worried that a lot of key information stored on CDs — from sound recordings to public records — is going to disappear. Some of those little silver discs are degrading, and researchers at the Library of Congress are trying to figure out why,” wrote Sarah Tilotta for NPR. “In a basement lab at the library, Fenella France opens up the door to what looks like a large wine cooler. Instead, it’s filled with CDs. France, head of the Preservation, Research and Testing Division here, says the box is a place where, using temperature controls, a CD’s aging process can be sped up.”

“France says part of what they are trying to do here is determine the minimal conditions needed for libraries and archives everywhere to preserve CDs.”

CBS News also featured a story on the Library’s research. “As for preserving the library’s collection, France and her team plan to test the CDs every three to five years to make sure as little as possible is lost to history.”

September 4, 2014

Pics of the Week: 2014 National Book Festival

Now in its 14th year, the Library of Congress National Book Festival welcomed book lovers to the Walter E. Washington Convention Center — a new venue for this year — on Saturday. More than 100 authors, poets and illustrators were featured throughout the day and evening, packing crowds into pavilions such as History & Biography, Poetry & Prose, Contemporary Life, Science, Fiction & Mystery, Children’s, Teen’s and Culinary Arts.

Throughout the day and after, festival-goers tweeted #NatBookFest their thoughts on the event:

“Great venue and incredible authors”

“Thanks @librarycongress for an excellent festival. Incredible experiences with so many authors. #NatBookFest is a national treasure”

“Was excellent yesterday. especially all the young readers, engaged and excited – the authors i saw were poised, clear, funny”

In the coming weeks, the Library will be posting videos from the festival presentations. In the meantime, here is a sampling of photos from the event to enjoy.

Crowds attend the National Book Festival, held for the first time at the Washington Convention Center. Photo by Colena Turner

Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin is interviewed by by National Book Festival Co-Chairman David M. Rubenstein. Photo by Shealah Craighead

[image error]

Chef Daniel Thomas demonstrates a recipe from his book, “Recipes for a New You: Healthy Eating at Its Best” in the new Culinary Demonstration pavilion. Photo by Ralphael Small

Great Books to Great Movies panel, featuring (from left) E.L. Doctorow, Alice McDermott, Lisa See and Paul Aster. Photo by Shealah Craighead

Festival attendee Hanna Fisher of Fairfax, Va., asks a question of Fiction and Mystery author Ismael Beah. Photo by David Rice

Evangeline Mackey, Library staff, reads to children at the 2014 National Book Festival. Photo by Ralphael Small

September 3, 2014

Civil Rights Act Exhibition Features Historical Documentary Footage

Considered the most significant piece of civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It banned discrimination in public accommodations, such as hotels, restaurants, theaters and retail stores. It outlawed segregation in public education. It banned discrimination in employment, and it ended unequal application of voter-registration requirements. The act was a landmark piece of legislation that opened the doors to further progress in the acquisition and protection of civil rights.

Next Wednesday, the Library of Congress opens the exhibition “The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom,” highlighting the legal and legislative struggles and victories leading to its passage, shedding light on the individuals – both prominent leaders and private citizens – who participated in the decades-long campaign for equality.

Six thematic sections in the exhibition – Prologue, Segregation Era, World War II and the Post-War Years, Civil Rights Era, Civil Rights Act of 1964 and The Impact – help patrons navigate through the exhibition.

Among the more than 200 items on display are several audio-visual stations featuring more than 70 clips showing dramatic events such as protests, sit-ins, boycotts and other public actions against segregation and discrimination, as well as eyewitness testimony of activists and from participants who helped craft the law. These materials are drawn from the Library’s American Folklife Center’s Civil Rights History Project and from the Library’s National Audio-Visual Conservation Center.

Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth discusses the violence he suffered in 1955 and 1957.

Here are a few highlights:

The only known sound recording made by Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) features the African American leader and educator reading an excerpt of the famous “Atlanta Compromise” speech that he delivered at the Atlanta Exposition on Sept. 18, 1895. The recording was made on Dec. 5, 1908, for private purposes and was made available commercially by Washington’s son in 1920. In his speech, Washington suggested African Americans should remain socially and politically segregated in return for basic education and improved social and economic relations between the races.

Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, one of the founders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and leading civil rights activist in Birmingham, Ala., discusses the bombings and beatings he suffered during a May 18, 1961 interview with CBS News. Shuttlesworth’s home was bombed Dec. 25, 1956, and he was later attacked by a mob in 1957 when he and his wife attempted to enroll their children in a former all-white public school.

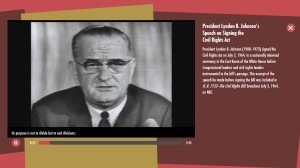

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, in a nationally televised ceremony in the White House before Congressional and civil rights leaders instrumental in the bill’s passage.

The thematic section focusing on the legislation itself features several pieces of documentary footage, including film footage of Oval Office deliberations prior to Kennedy’s national television address on civil rights; a debate about Kennedy’s speech among black leaders, including Malcolm X; and an NBC News clip of Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964 in a nationally televised ceremony at the White House.

“The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom” is made possible by a generous grant from Newman’s Own Foundation, with additional support from History for both audio-visual and educational outreach.

August 27, 2014

The Last Word: E.L. Doctorow

(The following is an article in the July-August 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM. Award-winning novelist E.L. Doctorow discusses the role of fiction and storytelling. You can read the issue in its entirety here.)

E.L. Doctorow. Photo by Gasper Tringale.

The story is the most ancient way of knowing. It preceded writing. It is the world’s first system for collecting and transmitting knowledge. It antedates all the empirical disciplines of a modern society. For millennia, it was the only thing people had.

In the Bronze and Iron ages purely factual discourse did not exist. There was no learned observation of the natural world that was not religious belief, no history that was not legend, no practical information that did not resound as heightened language. Science, poetry, the law and daily speech were fused. The world was a story.

From their first telling, stories were a means of survival; they were as essential as a spear or a club; they instructed the young, they connected the present to the past, and the visible to the invisible. They distributed the suffering so that it could be borne.

Stories are still a means of survival. As the channels of communication round the world fall into fewer and fewer corporate or government hands, the unaffiliated young writer’s witness is a trustworthy form of knowledge.

The publication of measured aesthetically worked fictions from the configured voices of writers is one way a nation composes its identity. Every story, every poem, if created honestly, with regard for a felt truth, contributes to a consensual reality, so that with each generation we may know who we are and what we’re up to.

Writers appear unbidden out of nowhere. Society does not give them credentials as it does doctors or lawyers or engineers. A writer may choose to earn a Master of Fine Arts degree, but that is more of a salute and wish of good luck than a license to practice. The writer’s only credential is self-conferred.

The writer of fiction stands outside the assemblage of experts that organizes the intellectual life of a society. Expert in nothing, the writer is not ruled by any one vocabulary and so is free to utilize any of them. He can write as a scientist, a theologian. He can be a philosopher or a pornographer. She can write as a journalist, a psychiatrist, an historian. She can, if she chooses, render the drugged hallucinations of poor mad souls in the streets. All of it counts, every vocabulary has equal value in the writer’s eyes, nothing is excluded.

In biblical times the writer’s inspiration was attributed to God. The modern writer understands that the writing of stories is itself empowering, that a sentence spun from the imagination confers

a heightened awareness, or degree of perception or acuity; that a sentence composed with the strictest attention to fact, does not. And so the knowledge we glean from a story may be unlike any other. The modern fictive voice continues to sound the world and find its meanings.

E.L. Doctorow will receive the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction at the Library’s 2014 National Book Festival this Saturday, Aug. 30.

August 25, 2014

Out of the Ashes

(The following is an article written by Guy Lamolinara, communications officer for the Center for the Book, featured in the September-October 2012 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. Aug. 24 was the 200th anniversary of the burning of the Capitol building and the Library.)

The story of the phoenix that rises triumphantly from its own ashes to live life anew is the story of how the Library of Congress survived its destruction during the War of 1812 to become the nation’s–and the world’s–pre-eminent source of knowledge and information.

An 1814 drawing shows the U.S. Capitol after its burning by the British. Print | George Munger, Prints and Photographs Division

On Aug. 24, 1814, the British occupied Washington, D.C., and burned the Capitol building. Inside, the congressional library went up in flames.

Two years before the conflagration, on June 18, 1812, President James Madison proclaimed that the Congress of the United States had declared war on the United Kingdom for “the wrongs which have forced on them the last resort of injured nations.”

When the Library of Congress burned, it was less than two decades old. In 1800, the year of the Library’s founding, as the new nation prepared to move its capital from Philadelphia to Washington, President John Adams signed into law a bill that appropriated $5,000 to purchase “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The money was used to acquire 740 books and three maps, ordered, ironically, from London. On the eve of the British attack on U.S. soil, Congress’s library had more than quadrupled to just over 3,000 books, maps, charts and plans, according to an 1812 catalog. Little would survive the conflagration.

From his home in Monticello, Va., retired President Thomas Jefferson wrote to his friend and political ally Samuel H. Smith, “I learn from the newspapers that the vandalism of our enemy has triumphed at Washington over science as well as the arts, by the destruction of the public library with the noble edifice in which it was deposited.”

Jefferson subsequently offered to sell his personal library–the largest and finest in the country–to Congress to “recommence” its library. After some political wrangling and arguments in Congress over why its members would need such a wide-ranging library as Jefferson’s–much of it in foreign languages–the United States purchased the 6,487 volumes for $23,950 in 1815.

To the doubters Jefferson replied, “There is, in fact, no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.”The ideal of a knowledge-based democracy was a cornerstone of the new republic and has remained so for more than two centuries. The far-ranging nature of the collections Jefferson assembled and his belief in the importance of a “universal” collection have ever since guided the Library’s collecting policies and are the key to the institution’s stature as a national–and world– library.

With the purchase of Jefferson’s books–collected over a period of 50 years–the Library effectively more than doubled in size. The new Library of Congress now contained volumes devoted to the arts and sciences as well as those that pertained to lawmaking.

On Dec, 31, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Ainsworth Rand Spofford to the post of Librarian of Congress. Located in the west front of the U.S. Capitol, the Library housed more than 82,000 volumes.

Spofford obtained congressional support for several legislative acts between 1865 and 1870 that ensured the growth of the collections and made the Library of Congress the largest library in the nation. The most important new measure was the copyright law of 1870, which centralized all U.S. copyright registration and deposit activities at the Library. The new law brought books, pamphlets, maps, prints, photographs and music into the institution without cost, thus assuring the future growth of the Americana collections and providing the Library with an essential and unique national function.

Published in Harper’s Weekly on Feb. 27, 1897, this print shows the congressional library in its overcrowded quarters in the U.S. Capitol. Librarian of Congress Ainsworth R. Spofford appears at far right. Print | W. Bengough, Prints and Photographs Division

In 1874, for the first time, the copyright law brought in more books than were obtained through purchase. The rapid growth of the collection necessitated a new home for the congressional library. The new structure, now called the Thomas Jefferson Building, was authorized by Congress in 1886 and completed more than a decade later. When it opened across the east plaza from the Capitol on Nov. 1, 1897, Librarian Spofford called it “the book palace of the American people.”

The Library of Congress began its expansion into a national and international institution under the leadership of Herbert Putnam, who served as Librarian of Congress from 1899 until 1939. The Library’s annex–later known as the John Adams Building–opened in 1939. The Library’s third Capitol Hill structure, the James Madison Memorial Building, opened to the public in 1980.

By 1992, the Library was the largest in the world and that year celebrated the acquisition of its 100 millionth item. For its burgeoning physical collections, the Library opened a high-density storage facility at Fort Meade, Md., in 2002. And in 2007, the Library opened a state- of-the-art audiovisual conservation facility at its new Packard Campus in Culpeper, Va.

On the eve of the 21st century, the institution was acquiring materials in all media, including digital. In 1994, the Library began to offer its collections online as part of its mission to make its materials as widely available as possible. Digitization efforts focused on rare and unique items such as the Gettysburg Address, the rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, the papers of Frederick Douglass, early maps and the first films of Thomas Edison. Since then, the Library has continued to add materials to its vast website, which now offers more than 31.4 million items. The World Digital Library website, which launched in 2008, offers content from 151 partner institutions in 75 countries, with metadata and expert commentary provided in seven languages.

By embracing technology and exploiting its potential, the Library has transformed itself into an essential–and readily accessible–resource for the nation as well as the world. And the institution has worked to extend its reach, not only making its collections more accessible on its own site, but also appearing on other content sites such as Flickr, YouTube and iTunes.

The Library of Congress– risen from the war’s ashes–continues to inform the national legislature and the world with its unparalleled collections.

John Y. Cole, Center for the Book Director and Library of Congress historian, also contributed to this article.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers