Library of Congress's Blog, page 158

July 2, 2014

Books Changed His Life

It is with great sadness that we convey to you, this evening, news of the passing of a great friend of the Library of Congress and all people who know the joy of reading – author Walter Dean Myers, winner of two Newbery Honors and five Coretta Scott King awards.

Walter Dean Myers

He served in 2012 and 2013 as the Library’s National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, and his theme was “Reading Is Not Optional.” Walter Dean Myers’ own life was an object example of how becoming literate can literally alter one’s future for the better. He not only wrote books with storylines compelling to young men of his own disadvantaged early background, but carried his message of the hope reading can bring to underserved and incarcerated Americans.

He spoke at the Library’s National Book Festivals in 2001, 2003, 2005 and 2012.

This man walked his talk. What follows is an endpaper he wrote for the September/October 2013 issue LCM, the Library of Congress Magazine:

**

Walter Dean Myers, the National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, believes in the power of reading to transform lives.

At a breakfast in Austin, Texas, some years ago, I was watching a group of librarians chatting over coffee and sweets when a man approached me and asked how I thought we could get more children reading. Assuming he was a librarian, I went into my usual spiel about getting young parents to read to toddlers. He replied, “Well, that’s all good, but do you think it’s actually going to happen?”

I did think that it could happen. I believed it then and I believe now as I finish my stint as National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

During the past decade I have spent a lot of time visiting juvenile detention centers around the country. I have continued to visit these facilities during my tenure as National Ambassador. The correlation between reading and success for these kids is clear and well-documented. I’ve spent years trying to figure out just how these young people went wrong and how we, as concerned and caring adults, could have intervened. I then asked myself how I escaped the traps they face.

Raised in a foster home by a barely literate mother and a functionally illiterate father, I was not a great candidate for National Ambassador of anything. When my mother worked, it was either in New York’s garment center or cleaning other people’s homes. However, when she wasn’t working, she would read to me. What she read were romance magazines and an occasional comic book. I didn’t understand what was going on in the magazines or much of what was going on in the comics, but I enjoyed the closeness of sitting on Mama’s lap and the sound of her voice in our small Harlem kitchen. I remember watching her finger move along the lines of type as she read and began to understand the connection between how the words looked on paper and how they sounded.

Later, I would be disappointed in my mother as alcoholism claimed much of her life and all of our closeness. After my uncle was murdered, my father plummeted into a depression that further added misery to the already angst-ridden family. I dropped out of high school, but I was already a reader. Even when I was fighting in gangs, I would spend my non-combat moments alone with the new friends I had found—Balzac, Shakespeare, Thomas Mann.

Over the last two years I’ve seen an American literacy problem that is growing. This year the high school graduation rate in New York decreased. Also decreasing is the number of young people achieving the high level of reading competency required for today’s workplace.

We are, as a nation, interested in solving the problem. The man I assumed was a librarian in Austin turned out to be Texas Gov. Rick Perry. He wanted a simple and direct solution to the problem, and I wanted to help.

I still do, and I will continue trying to spread the word about the importance of reading. I am working with the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress and the nonprofit literacy organization Every Child a Reader to establish a neighborhood reading center in New York.

The nation has to avoid the easy path of giving up on children because their parents and communities can be difficult to involve. I believe Americans are too good, and too generous a people, to let that happen.

July 1, 2014

Letters About Literature: Dear Dr. Seuss

Letters About Literature, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives, announced its 2014 winners last month.

More than 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative, a reading-promotion program of the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress.

The top letters in each competition level for each state were chosen. Then, national and national honor winners were chosen from each of the three competition levels: Level 1 (grades 4-6), Level 2 (grades 7-8) and Level 3 (grades 9-12). For the next several weeks, we’ll post the winning letters. Winners came from all parts of the country and wrote to authors as diverse as Dr. Seuss, Sharon Draper, Anne Frank, Ray Bradbury, George Orwell and Jhumpa Lahiri.

There was a tie for the national prize for Level 1. Following is one of the winning letters written by Becky Miller of Wellesley, Mass., to Dr. Seuss, author of “One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish.”

Dear Dr. Seuss,

When I was little, I remember reading “One Fish Two Fish, Red Fish Blue Fish” at night before I went to bed, and being so absorbed in it I wouldn’t put it down. It would leave me with such a great feeling I wouldn’t want to stop reading; it was my favorite. Eventually, though, my mom would come in and tell me to go to sleep, and I always dreaded that point. I felt as if that visit was the moment my room came back to life, and I bounced back to reality. But sadly, I don’t get those visits anymore. About a month ago, my mother passed away with brain cancer.

My mom always had a love of reading. She would read a 200-page novel in two hours if you let her. She could read on and on and on. Most of the books she read were trashy novels, with no definite purpose except to entertain. But my mom would read me any book in the universe if l asked her to, simply because she wanted to share her love of reading with everyone. We read “One Fish Two Fish” so many times, I can’t imagine how she didn’t feel as if she had written it herself, but the funny pictures, the made-up words, the voice — it made us both escape into a place we couldn’t explain. It was wonderful and so exciting it left me with a lasting impression of books I’ll never forget. These memories were some I will always cherish. They connected me to my mom and I hope one day, if l have a family, I will share this memory with my kids and pass it on. I hope I will be just like my mother, because these memories were some I shared with her.

Once, when I was about eight years old, my mom and I cleaned out my bookshelf. It was overflowing with picture books, books I had gotten as presents, and the books my mom had saved since she was a little girl. We took every single book out and made three piles: the Keep pile, the Throw Out pile, and the Keep in the Attic pile. I would take the books that no one read anymore, put them in the Throw Out pile, and as soon as my mom saw what I had done, she’d say, “NO! We have to keep this one. Don’t you remember reading this before?” I’d say, “Mom, I’m never going to read that. If you really want to keep it put it in the Attic pile.” Pretty soon the Attic pile was by far the biggest one. We stored them up there, but they were soon long forgotten, isolated from small children’s hands and eagerness to read for so long. I still have those Attic books, and I haven’t looked at them in forever. My mother cared way too much about the memories of reading books with my brother and I when we were kids, to throw them away. She and I wanted to hold on to the happy past and the fun memories. I realized that I would be okay as long as I didn’t let go of our time together, just like neither of us let go of our memories reading “One Fish Two Fish.”

One of the only books in the Keep pile was “One Fish Two Fish.” It was the memory that always made neither of us want to let it go. Whenever I miss my mom, I can read it and remember the way her voice sounded and how safe and warm we felt with each other. The way she’d fall asleep on my bed sometimes if we read late enough. Even if l can’t be with her, I can still turn to what we both held on to. I’ll always have that.

“Today was good. Today was fun. Tomorrow is another one.” —Dr. Seuss

Becky Miller

June 28, 2014

See It Now: Our Fourth President

James Madison. Between 1836-1842. Prints and Photographs Division.

On June 28, 1836, President James Madison passed away at age 85 – the last of the nation’s Founding Fathers. His public service had a symmetry to it. He had served in several positions, each for eight years: first as a member of Congress, followed by the same span as Secretary of State, then finally eight years as President of the United States. Even after that, he served eight years as director of the University of Virginia after Thomas Jefferson’s death.

Madison was also a president of firsts – often referred to as the “Father of the Constitution,” Madison wrote the first drafts of the important document, as well as the Bill of Rights. In 1792, he and Jefferson founded the Democratic-Republican Party, which has been called America’s first opposition political party.

According to Pulitzer-prize winning historian Jack N. Rakove, Madison was an intensely private man who sought only to be known by his public deeds. In fact, in his retirement after 1817, he edited a good bit of personal material out of his papers to reinforce that message.

Rakove spoke about Madison during a special event at the Library earlier this year, and the webcast is now available here.

Madison’s papers make up part of the Library’s collection of presidential papers. Included are materials documenting his activities as a member of the Continental Congress, his role in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, his tenure as secretary of state during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson and his two terms as president. Noted correspondents include George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Noah Webster and James Monroe. Also included in this collection are a copy of Madison’s autobiography and his correspondence with his wife, Dolley.

Scattered throughout the institution’s various collections, online exhibitions and other resources are assets pertaining to Madison, all collected in this guide.

June 27, 2014

Bringing the “Banner” to Light

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette, in honor of the Star Spangled Banner, which celebrates its 200th anniversary this year. To commemorate the anniversary, the Library is hosting a concert featuring baritone Thomas Hampson on July 3.)

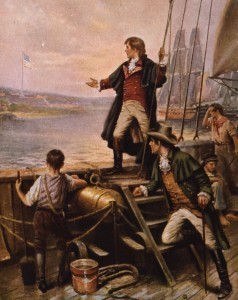

Francis Scott Key watches the bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814. Prints and Photographs Division.

The story of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” for many decades, seemed as murky as the smoky haze over Fort McHenry on the morning two centuries ago when Francis Scott Key wrote the lyrics that still inspire a nation.

No one knew for sure who wrote the music. No one fully understood the circumstances of the tune’s creation (but, no, it wasn’t a bawdy English drinking song). No one fully understood how Key’s words became connected to the music or how they were disseminated.

Much of what is known about “The Star-Spangled Banner” now – at the anthem’s 200th anniversary – is known because of research conducted by Music Division librarians or with Library of Congress collections. For more than a century, the Library has served as the principal research center for the national anthem.

“We’ve been collecting, documenting, researching and making available this information since 1909,” Music Division librarian Loras Schissel said. “The piece has been printed and reprinted from 1814 to the Civil War. All the different versions that occurred during that period are here through collecting, purchasing, gift or copyright deposits.”

By Dawn’s Early Light

Key, detained aboard a British warship, watched British ships bombard Fort McHenry in Baltimore Harbor in September 1814. The assault failed, and at dawn on the 14th, Key saw the U.S. flag still there, streaming over the fort’s ramparts. Inspired, he composed the lyrics to what 117 years later became the national anthem.

Key wrote with a particular tune in mind: “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a piece composed as the official song for an 18th-century London club of amateur musicians and, later, widely adapted for other uses.

Key’s lyrics – set to the “Anacreon” melody and soon titled “The Star-Spangled Banner” – over the decades became one of America’s most popular patriotic songs. In 1931, Congress declared the song the official anthem of the United States.

[image error]

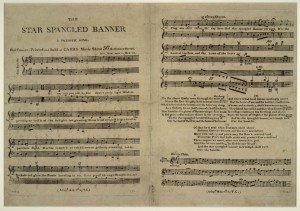

First edition of “The Anacreontic Song.” Music Division.

Library collections contain hundreds of pieces related to the “The Star-Spangled Banner,” collectively tracing its evolution from London music club anthem to national anthem of a growing, powerful country an ocean away. The Library holds, for example, the first printed lyrics of “To Anacreon in Heaven”; the first printed sheet music of that song; Key’s own copy of “Anacreon”; the first printing of Key’s lyrics, circulated in Baltimore just days after the battle; the first printed sheet music setting Key’s lyrics to the “Anacreon” tune and bearing the title “The Star-Spangled Banner”; and the lyrics handwritten by Key years later.

“Taken together, we have the whole story,” Music Division librarian Raymond White said.

An Uncertain History

That story, however, remained murky long after Key’s work became one of America’s most popular patriotic songs. Little was known about the London music club, the Anacreontic Society. The identity of the composer of “To Anacreon in Heaven” was unclear; the song frequently, it turned out, was attributed to the wrong composer. It wasn’t clear how Key became familiar with the tune or how his lyrics were spread.

Much of the scholarly work of locating, comparing and evaluating – often contradictory – information about the song was done by researchers using Library resources or by Music Division librarians examining numerous editions of music and lyrics, newspaper reports and other documents.

“What it comes down to is looking at printed sources, which are not unique but extraordinarily rare,” White said. “The story of this thing plays itself out in these printed sources.”

Composer and bandleader John Philip Sousa, conducting research at the Library, in the late 19th century produced the first serious study of the piece. (Sousa also gave “The Star-Spangled Banner” its first official status: On his recommendation, the Navy required the piece to be played each morning as the flag was raised.)

Over the next nine decades, Music Division librarians expanded on Sousa’s work and ultimately wrote the anthem’s definitive story.

A Watershed Report

The first printed edition combining the words and music of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Music Division.

Oscar Sonneck – Music Division chief from 1902 to 1917 – was perhaps America’s first great musicologist. He wrote a bibliography of American secular music, devised the music-classification system still used by many of the world’s libraries and – determined to make the Library one of the world’s great music repositories – began collecting important material.

“He is, perhaps, the most important music librarian in the world,” Schissel said. “His ideas still are standard.”

In 1909, Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam asked Sonneck to produce a report on America’s most important patriotic songs: “Yankee Doodle,” “Hail, Columbia,” “America the Beautiful” and “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Sonneck’s work helped establish, among other things, how Key’s lyrics became connected to the “Anacreon” music, when and how the first editions were printed, and that Key was thinking of “Anacreon” when he wrote the lyrics.

Sonneck also helped resolve the lingering mystery of the “Anacreon” composer. Samuel Arnold, among others, had been prominently suggested as its creator. Sonneck, however, sifted the evidence and concluded that an obscure London church organist, John Stafford Smith, likely was the composer.

Later, Sonneck played a key role in establishing a definitive version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” At the request of President Woodrow Wilson, Sonneck headed a committee charged with creating a “standard” version that could be taught and performed consistently. (The original manuscript is in the Library collections.)

“That’s the big step toward 1931,” Schissel said. “Wilson’s saying, ‘When it’s appropriate to play a national anthem, I’d like it to be ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’ That’s another push toward anthemhood.”

Putting it all Together

Music Division librarian Richard Hill carried on Sonneck’s work in later decades, establishing proof of the basic conjectural things Sonneck and Sousa had come up with and adding detail about the Anacreontic Society and Smith.

“He put it all together: This was printed at this time. This edition came out then. The Anacreontic song was first published at this point,” Schissel said. “And, among other things: Who was John Stafford Smith? He was a murky figure in this operation.”

Hill died relatively young, in 1961, leaving his work unfinished.

Music Division librarian William Lichtenwanger took Sonneck’s and Hill’s research, added his own and in 1977 produced the work now considered the anthem’s definitive history: “The Music of The Star-Spangled Banner: From Ludgate Hill to Capitol Hill.”

“It basically should be a three-name book: Sonneck, Hill and Lichtenwanger,” Schissel said. “We’re always looking for new information, we’re always looking for new editions, we’re always adding to our knowledge. But that book still is cited. It’s always used.”

June 24, 2014

Inquiring Minds: A Voyage of Musical Rediscovery

Pianist Alex Hassan’s passion is music, but not just any music – he lives to recreate the Tin Pan Alley melodies of the 1920 and 1930s. The classically trained musician, who says he is a pupil of pupil of a pupil of Franz Lizst, has, in his own words, “tunnel vision” for the popular musical styles and arrangements of the bygone era. But his interests lie in the discovery of what he calls “musica obscurae,” works from the time that often went unpublished. He performs them as part of the trio, Three For a Song, featuring soprano Karin Paludan and tenor Doug Bowles. In addition, Hassan is an avid collector of these works, having currently amassed some 45,000 pieces of sheet music.

“The significance of these ‘music obscurae’ allow me to quote Doug Bowles: ‘Your favorite songs were once songs you didn’t know,’” he said.

Hassan has been a fan and avid researcher of the Library of Congress collections for many years. He first began researching in the early 1970s.

“The Performing Arts Reading Room has been a second home for decades,” he said. “Happily, the greatest, most accessible library in the world is minutes away.” Hassan lives in Falls Church, Va.

Hassan recalls his experiences searching the Library’s stacks some 30 years ago. “I regularly had stack passes and can honestly state that all important piano solo collections were meticulously perused.” (The Library’s stacks have always been closed to the public, but exceptions were once made for scholars and others who verified a need to browse in designated areas.)

Working with reference librarians, Hassan discovered the Library’s “It’s Showtime” collection, which “proved a goldmine” for his performances.

“Many of the stunning finds have entered both my repertoire and those of singing friends Kari Paludan and Doug Bowles in our performances,” he said. “An early program of ours in the Coolidge Auditorium was an adjunct to [retired Music Division senior cataloging specialist] Sharon McKinley’s luncheon talk on the database.”

Most recently, Hassan has been working with the papers of American composer and film producer Arthur Schwartz and materials from the Warner-Chappell archives, a collection of manuscripts from Warner Bros. music publishing company. According to him, he’s made many discoveries, including an unpublished work by Herman Hupfeld, who wrote “As Time Goes By” in 1931 (not written for “Casablanca,” Hassan says). The score was for a show, “One More Night,” staring noted chanteuse of the time Irene Bordoni, which closed before reaching Broadway.

“The title song has one of those soaring romantic melodies that stays in the memory,” he said.

Speaking of melody, that’s why Hassan has developed such in interest in these sounds of the 1920s and 1930s. During that time, melody was in the forefront of the songs, he said. He also feels that the music of that time lends itself to his piano-playing style.

“There was such a proliferation of melody in the 1920s and 1930s that a ton of stuff of equal merit never had a chance,” he explained. “The explorer in me has always prevailed, and I’ve been a torch-bearer for the songs that didn’t make it.

“The standards will always be there: ‘Star Dust,’ ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’, ‘Summertime,’ ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,’ ‘Stormy Weather,’ ‘Over the Rainbow,’” he continued. “We’re the drum majors for the songs that, for a variety of reasons, didn’t have the snowball’s chance.”

The Library’s efforts to preserve such historical musical collections are, to him, a blessing.

“There’s no other library in the world with the quality and quantity and, importantly, accessibility of collections,” Hassan concluded. “May I continue to beg the wonderful staff’s forgiveness for my continuing gluttony.”

June 20, 2014

Let’s Get Pinning!

Today the Library of Congress launched its own Pinterest account, continuing efforts to make educational, historical and cultural resources available to web users across many platforms.

With Pinterest, the Library can share visual content with a wide audience, allowing them to also curate their own collections featuring the same content by creating and managing “boards” and “pinning” items. Each pin links back to the original Library source material.

The Library is the repository to more than 158 million items of cultural and historical value, including more than 13.7 million photographs, 5.5 million maps, 6.7 million pieces of sheet music and 69 million manuscripts.

The Pinterest account joins other social-media platforms, including YouTube, Flickr, Twitter and Facebook.

June 19, 2014

Pic of the Week: Octavia Spencer

Photo by Amanda ReynolAward-winning actress Octavia Spencer visited the Young Readers Center earlier this week to discuss her children’s book, “Randi Rhodes, Ninja Detective: The Case of the Time-Capsule Bandit,” with students from Roots Public Charter and Orr Elementary in the District of Columbia, and Oak View Elementary School in Fairfax, Va.

Schools were from at-risk communities, and Spencer shared her own personal story growing up with dyslexia in a very small town in Alabama. The actress won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her role as Minny in the 2011 film “The Help.”

“Randi Rhodes, Ninja Detective: The Case of the Time-Capsule Bandit” is the first in a series, with the second forthcoming next summer.

June 16, 2014

See It Now: Happy Bloomsday

James Joyce. 1941. Prints and Photographs Division.

Several years ago I took a whirlwind tour of Ireland, which included a few days in Dublin. One of my most memorable experiences was taking a literary pub crawl through the city. Throughout the evening, the actor tour guides led us in the footsteps of James Joyce, Samuel Beckett and Oscar Wilde, among others.

While I can’t quite remember all the spouted prose, I’m sure our guides likely entertained us with selections from Joyce’s most seminal work, “Ulysses.” Today, June 16, marks Bloomsday, a celebration of the early 20th century Irish author and a nod to the novel, which recounts a day in the life of protagonist Leopold Bloom on June 16, 1904.

St. Olaf College student Johnna Purchase interned at the Library last year, where she worked in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division. She used her time to examine the material and cultural history of Joyce and his works, among other things. (You can read more about her internship here. Purchase delivered a lecture at the Library discussing her research, which you can see below.

{mediaObjectId:'FB30ADD61A94023EE0438C93F028023E',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

Joyce also published several books of poetry. His book, “Chamber Music,” is a collection of 36 of his poems. Noted composer Samuel Barber was much influenced and inspired by Joyce’s writing. In 1936, he composed a series of songs set to poetry from “Chamber Music”: “Rain has fallen,” “I hear an army,” and “Solitary hotel.” Available as part of “The Library of Congress Celebrates the Songs of America” presentation are audio and video recordings of these songs featuring baritone Thomas Hampson, who will perform at the Library July 3.

For more Joycean resources, search for “James Joyce” in the Library’s online catalog for a list of several electronic book resources.

June 11, 2014

Rare Map on Display at Library Scored Some “Firsts”

(The following is a guest post by Wendi A. Maloney, writer-editor in the U.S. Copyright Office.)

[image error]

Abel Buell, “A New and Correct Map of the United States of North America,” 1784. On deposit to the Library of Congress from David M. Rubenstein.

Engraver Abel Buell “came out of nowhere,” at least in terms of cartography, when he printed a United States map in 1784. “He’d never done a map before,” says Edward Redmond of the Library’s Geography and Map Division. Nonetheless, Buell set records.

He was the first U.S. citizen to print a map of the United States in the United States after the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783. The treaty formally concluded the American Revolution and recognized the United States as an independent nation. Buell was also the first person to copyright a map in the United States.

Buell’s “New and Correct Map of the United States of North America” is the centerpiece of “Mapping a New Nation,” an ongoing exhibition in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress. Philanthropist David M. Rubenstein purchased Buell’s map at auction in 2010 and made it available for public display at the Library.

The wall map contains no original cartographic material, Redmond says; instead, Buell combined elements of maps published earlier in Europe.

“Buell, who lived in New Haven, Connecticut, may have accessed other maps at nearby Yale University,” Redmond suggests. “That’s a supposition, however; we can’t prove it.”

Redmond worked with other Library colleagues to identify maps in the Library’s collections that Buell may have used as sources and include them in the exhibition. “As the largest map library in the world, we have in our collections the maps Buell likely would have had available to him,” Redmond says.

Buell’s map documents a unique time in U.S. history. “Before adoption of the Constitution in 1787, the federal government couldn’t establish boundaries between states or force surrender of the western lands some states claimed,” Redmond notes. “As a result, the boundaries of many states in Buell’s map extend west from the Atlantic Coast all the way to the Mississippi River.”

Buell petitioned the General Assembly of Connecticut for a copyright for his soon-to-be-printed map on October 28, 1783, nine months after Connecticut became the first U.S. state to enact a copyright law. By October 28, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Jersey had also passed copyright laws, but none expressly protected maps, as Connecticut’s law did. Thus Buell became the first person to copyright a map in the new nation.

Lawrence Wroth, Buell’s biographer, described Buell as creative and versatile but also restless and impulsive, which perhaps explains his conviction in 1764 for counterfeiting. Buell served jail time, had the tip of his ear cut off, and had his forehead branded with the letter C, a standard penalty of the time.

His colorful life notwithstanding, Buell had the skill and wherewithal to create his own “cartographic conception of the United States,” rich in symbolism of the emerging nation, Redmond concludes.

June 9, 2014

A Book Festival for the Bird(er)s

“Shirley,” the celebrated Cooper’s Hawk liberated from the cupola of the Library’s Main Reading Room early in 2011. She was identified by a Library staffer using a Sibley app.

David Allen Sibley – yes, the author of the recently updated “Sibley Guide to Birds,” that indispensable handbook on all things feathered – will appear at this year’s National Book Festival, Saturday, August 30 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center.

In addition to this most highly respected ornithologist, we will also welcome Sally Satel, co-author (with Scott Lilienfeld) of “Brainwashed: The Seductive Appeal of Mindless Neuroscience,” Ian Morris, author of “War! What Is It Good For? Conflict and the Progress of Civilization from Primates to Robots” and former National Basketball Association star Derek Anderson.

Tweet it, squawk it, send it via carrier pigeon, release it from the Main Reading Room: the Library of Congress National Book Festival will bring more than 100 authors for all ages to the Washington Convention Center August 30, for a full day followed by all-new evening activities including a graphic novels “super-session,” a poetry slam and a screening titled “Great Books to Great Movies.”

It’s all free and open to the public. Don’t miss it!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers