Library of Congress's Blog, page 161

April 21, 2014

WDL Marks 5 Years of Sharing Cultural Treasures with Globe

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

Director John Van Oudenaren delivers a presentation about the World Digital Library to Kenyan librarians, archivists and government officials in Nairobi in 2013. Photo by Pamela Howard-Reguindin,

The idea was as big as the planet itself: Gather and digitize the globe’s cultural treasures, assemble them on one website and make them available to the world for free and in multiple languages. Such a project, Librarian of Congress James H. Billington said in proposing it, would bring people together by “celebrating the uniqueness of different cultures in a single, shared global undertaking.”

Today, the World Digital Library – the international project inspired by Billington and led by the Library of Congress – will mark its fifth anniversary of online operation.

The World Digital Library launched on April 21, 2009, with 26 global partners in 18 countries and some 1,200 items in its online collections. Today, the network has 181 partners – mostly archives, libraries and museums – in 80 countries that collectively have contributed more than 10,000 manuscripts, maps, books, prints, photographs, journals, newspapers, sound recordings and motion pictures.

The online collections contain a wide range of great primary cultural and historical documents: The U.S. Constitution, the Japanese work considered the world’s first novel, the magnificent illustrated Bible of Borso d’Este, ancient Arabic works on algebra, a 2,200-year-old papyrus fragment of Euripides’ play “Orestes,” an African rock painting of an antelope that is perhaps 8,000 years old.

The project’s appeal, director John Van Oudenaren said, lies in the breadth of the collection and the high quality of the objects and presentation.

“What’s really been striking is how the libraries – some very great libraries – have put forward their top things,” Van Oudenaren said. “They’ve put forward fantastic, rare things. It’s kind of astounding what people send.”

Those fantastic, rare things span the globe: The collection items represent countries from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe and 192 nations in between.

Part of the World Digital Library’s groundbreaking mission lies in the presentation: Each item is provided with consistent metadata; translated into Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish; and presented with high-resolution, deep-zoom photos that reveal even the paper fibers in the First Folio of Shakespeare’s plays. Those images – now nearly 500,000 in number – allow visitors to inspect each note of “The Magic Flute” in Mozart’s original handwritten score; navigate each Mexico City street via a map drawn just after the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs; or examine each calligraphic stroke in a Holy Qur’an from Iran’s national library.

“The World Digital Library is a very intensive, value-added project,” Van Oudenaren said. “There are digital-library projects of all kinds. Some focus on aggregating metadata and putting a lot of content online without really upgrading. World Digital Library is different. We take content at different levels of enrichment in terms of metadata and raise it to a single level.”

The site’s audience is as global as its content. In its first five years, the World Digital Library attracted nearly 30 million users from 231 international jurisdictions around the world, drawing visitors from continent-spanning countries (Russia, Australia) and tiny island territories (Kiribati, Wallis and Futuna) alike. Spain, Brazil, Mexico, the United States and China provide the most visitors, and Spanish, English and Portuguese are the most-used languages. Increasingly, visitors come from Arabic-speaking countries across Africa and the Middle East: Arabic now ranks fourth in use on the site.

Going forward, the World Digital Library aims to expand the depth and geographic range of its collections and partner institutions – ideally gaining at least one partner in each country.

“We’ve got partners in 80 countries, but there are 194 countries in the world so it still leaves an awful lot of countries we’d like to recruit,” Van Oudenaren said.

The project also helps countries with limited digitization capacity contribute. The World Digital Library has established digitization centers in Baghdad, Cairo and Kampala, Uganda.

“We try to use the World Digital Library as a vehicle to help developing-country institutions participate,” Van Oudenaren said. “We’d like to do more of that.”

Over the past few years, the World Digital Library has made steady improvements to the user interface: The site now features a better page viewer, for example, and full text search of both the metadata and the English, Arabic and French books in the collection.

A major upgrade also is planned for later this year. The World Digital Library will relaunch as a beta site with a redesigned interface, interactive maps, and thematic timelines and in a form more user-friendly for mobile devices.

The mission, however, will remain the same as the one Billington first put forward nine years ago: making available the cultural treasures of the world and putting them online for free for educators, scholars and the public.

“It’s been wonderful to show all this great cultural material to the world,” Van Oudenaren said. “People have fascinating things. You just don’t know what’s out there until you start bringing it together. “It’s been a huge ambassador on the part of the Library.”

April 18, 2014

Adiós, Gabo

One of the most popular features in the Library of Congress Pavilion at the Library’s National Book Festival is a whiteboard on which you can write the name of a book. Some years we ask for your favorite book. Some years we ask what book shaped the world. People stand a few feet back, ponder, look at what others write, and then step forward and put up their title.

Every year, for me, it’s the same: “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez, a native of Colombia and master of modern letters who died on Thursday in Mexico City at age 87.

Books Populi at the Library’s 2013 National Book Festival

In my lifetime of reading – a lifetime made wonderful by reading – it is, quite simply, my favorite book.

I was assigned to read this towering novel by Prof. David Cusack at the University of Colorado back in the 1970s. He was teaching a course in Latin American political science. It was odd to be assigned a novel as required reading for a PolySci course, but Prof. Cusack—who had spent a lot of time in Latin America—explained that it would help us understand a different worldview from our own, a different lens for looking at reality. It would help us understand how things were different there.

And so, I tackled this assigned book – and was swept along as if I had fallen into the Amazon in flood. I ripped through that book as if my own future were written in it. Many books take us to “other worlds” but this one – this one was literally otherworldly (Márquez’s style is often referred to as “magical realism”). I absolutely loved it – I read it again, immediately, bought extra copies and began giving them to other people I cared about, including my father, a newspaper columnist.

He liked it so well that in his annual column thanking various people, he thanked me for pointing him to it, and in doing so tipped about 250,000 Denver Post readers off to this astounding modern classic.

You may also enjoy many of this Nobel-winning writer’s other books as well – I enjoyed “Love in the Time of Cholera” and the novella “No One Writes to the Colonel.” Márquez, known as “Gabo” to his friends, wrote many novels and stories, and we have a recording of him reading from his own work in the Library’s Archive of Hispanic Literature on Tape, in the Hispanic Division.

Do I remember anything else about that political science course? No. But I maintain a fond memory of Prof. Cusack, who was also involved in early efforts to introduce the United States to the grain known as quinoa. On a trip to Bolivia to work with quinoa farmers, he was in the wrong place at the wrong time, and was fatally shot.

So, adiós, Master Márquez, and rest in peace, Prof. Cusack. Together, you gave us a great gift.

Letter to the Editor

(The following is a guest post by Barbara Bair, historian in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division.)

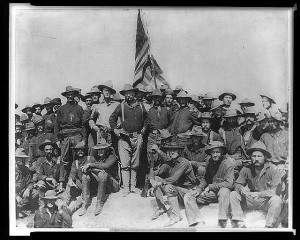

Colonel Roosevelt and his Rough Riders, Battle of San Juan. Prints and Photographs Division.

While life posed many setbacks for Teddy Roosevelt (1858-1919), he proved himself a man who met challenges and seized his opportunities. When it came to the Spanish American War in 1898, Roosevelt carefully devised public acclaim as a manly military leader of the First Volunteer Cavalry. He rode that reputation all the way to the governorship of New York and then the White House. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, meanwhile, evolved from actual soldiers participating in warfare into heroic status in the American popular imagination (and Wild West shows) as a rabble-rousing courageous band of westerners and easterners who triumphed at San Juan Hill.

A letter recently acquired by the Library of Congress’ Manuscript Division sheds light on some of the details behind the Rough Riders’ story. Modern historians continue to look backward and debate the military prowess of the regiment. Roosevelt himself noted the general confusions and lack of preparedness of the United States War Department in his diary. The letter shows that Roosevelt felt moved to personally respond to aspersions being cast specifically against his men. He wrote to defend their honor at a time when they were fresh from the victory that brought them fame.

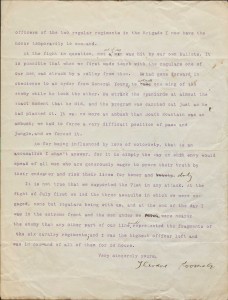

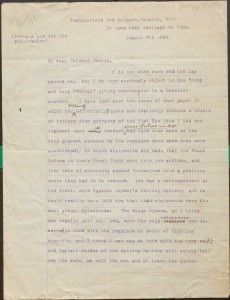

The two-page letter, marked “(Private and not for publication),” was composed on a typewriter at headquarters camp for the 2nd Brigade, Cavalry Division, near Santiago de Cuba on Aug. 4, 1898. It was signed by Roosevelt and edited in his hand. It was directed with characteristic Roosevelt energy to Col. William C. Church, founder and editor of the Army and Navy Journal.

Roosevelt wrote to contest certain allegations that were being aired in military circles claiming that the Rough Riders’ performance had been less than stellar. Among the charges that Roosevelt termed “baseless slander” were the ideas that the Rough Riders had been ambushed, engaged in ill-advised fame-seeking from which they required rescue or were guilty of friendly fire. Roosevelt proclaims these rumors to be “absurd falsehoods” and attributes them to envy on the part of members of a rival volunteer unit from the 71st New York.

At issue was, in part, who to believe about the chaotic happenings of war. Roosevelt questions Church’s failure to fact check the reports with a correspondent in the field and lends his own account of what happened in the unit’s two major encounters.

Excerpts from Theodore Roosevelt to Colonel Church, August 5, 1898. Theodore Roosevelt Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress:

“The Rough Riders, as I think any regular will tell you, were the only volunteers who deserved to rank with the regulars in point of fighting capacity . . . . As for being influenced by love of notoriety, that is an accusation I shan’t answer . . . . At the fight of July first we led the three assaults in which we were engaged, none but regulars being with us, and at the end of the day I was in the extreme front and the men under me were nearer the enemy than any other part of our line …”

Roosevelt was assistant secretary of the Navy when the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898. Roosevelt strongly favored American military intervention against Spain in the Cuban insurgency, especially after the sinking of the battleship U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor in February. Eager to participate first-hand in military combat, he resigned his administrative post to help recruit a volunteer unit that would combine the two social worlds of most interest to him: cowboys from the West and adventuresome Ivy League athletes from the East.

[image error]

Wm. H. West’s Big Minstrel Jubilee: “The Charge of San Juan Hill.” Ca. 1899. Prints and Photographs Division.

Arriving in Cuba in June, the volunteers, who had trained in San Antonio, Texas, and traveled via Tampa, Fla., saw their first battle on June 24 against Spanish fortifications in mountainous jungle terrain at Las Guásimas. Eye-witness correspondent Richard Harding Davis termed the fighting in the difficult surroundings more hot and hasty than he could ever have imagined. Their renown came on July 1 with the battle of San Juan Heights, in which Roosevelt pressed to the forefront as senior in command and led the infantry charge on Kettle Hill. The Spanish were meanwhile challenged by sea as well as by land. The U.S. Navy won the decisive naval battle at Santiago harbor on July 3, and the city was surrendered on July 17. While some had their qualms about both the virtue and the conduct of the conflict and of the United States’ reach into Imperialism, many Americans responded like Secretary of State John Hay, who termed the conflict “a splendid little war.” Roosevelt soon codified his own heroics in his 1899 war memoir, “The Rough Riders,” and in copious coverage in the popular press.

April 16, 2014

E.L. Doctorow Awarded American Fiction Prize

E. L. Doctorow, author of such critically acclaimed novels as “Ragtime,” “World’s Fair,” “Billy Bathgate,” “The March” and his current novel, “Andrew’s Brain,” is the second recipient of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. He will receive the award during this year’s National Book Festival, scheduled for Aug. 30 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C.

The annual Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction is meant to honor an American literary writer whose body of work is distinguished not only for its mastery of the art but for its originality of thought and imagination. The award seeks to commend strong, unique, enduring voices that—throughout long, consistently accomplished careers—have told us something about the American experience. Winning the award last year was author Don DeLillo.

“I was a child who read everything I could get my hands on,” Doctorow said. “Eventually, I asked of a story not only what was to happen next, but how is this done? How am I made to live from words on a page? And so I became a writer myself.

“But is there a novelist who doesn’t live with self-doubt? The high honor of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction confers a blessed moment of peace and resolution.”

Librarian of Congress James H. Billington chose Doctorow based on the recommendation of a panel of distinguished authors and prominent literary critics. ”E. L. Doctorow is our very own Charles Dickens, summoning a distinctly American place and time, channeling our myriad voices. Each book is a vivid canvas, filled with color and drama. In each, he chronicles an entirely different world.”

Doctorow’s career spans more than 50 years. He has written a dozen novels, starting with “Welcome to Hard Times” (1960). He has received the National Book Award for Fiction, the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction and the PEN/Faulkner Award. In addition to awards for his individual works, his body of work has been honored with the National Humanities Medal (1998), the New York Writers Hall of Fame (2012), the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction (2012) and the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters of the National Book Foundation (2013).

The Prize for American Fiction follows in the path of the Library of Congress Creative Achievement Award for fiction: John Grisham (2009), Isabel Allende (2010), Toni Morrison (2011) and Philip Roth (2012). In 2008, the Library presented Pulitzer-Prize winner Herman Wouk with a lifetime achievement award in the writing of fiction. This honor inspired the Library to grant subsequent fiction-writing awards.

April 15, 2014

Experts’ Corner: Image Researching

The following is an article featured in the March-April 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

Athena Angelos. Photo by Shealah Craighead.

Athena Angelos, image researcher for many Library of Congress publications, discusses the process of visual reference work.

How did you prepare for a career in image research?

I’ve always loved photography and looking for things. If you’ve lost a pearl in a white shag carpet, you should call me. When I was about 10 years old, my father let me start using his WWII-era Leica camera, which he purchased from the PX. I went on to get a bachelor of science degree in fine art at the University of Wisconsin with an emphasis on photography. When I returned to Washington, D.C., after college a friend put me in touch with a book packager who needed someone to “look for old photos at the Library of Congress.” I had never heard of picture research but this sounded more appealing than the house-painting I was doing at the time.

Looking back on my career, I have to mention that my success in the field and my enjoyment of the work has been dependent on the assistance I have received from many talented Library of Congress reference librarians, curators, catalogers and other specialists.

You have researched images for a number of Library of Congress publications. Can you tell us about those projects?

I was very fortunate that my first client, a book packager, had contracts with the Library of Congress Publishing Office for four multi-volume series of books. This provided me with about three years of work and was an excellent training period to learn about the Library’s vast array of materials and how to access them. The four series covered Colonial America, The American West, The U.S. Presidents and the Civil War. Over the years, I’ve conducted image research for many other Library publications such as “The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference,” “The Library of Congress Illustrated Timeline of the Civil War,” “The Library of Congress World War II Companion,” “World War II 365 Days,” and many calendars such as those in the “Women Who Dare” Series. My most recent project was image research for “Football Nation: Four Hundred Years of America’s Game.”

Can you tell us about your research process for “Football Nation”?

The process of working on “Football Nation” with author Susan Reyburn of the Library’s Publishing Office was dynamic and fun. We laughed a lot—quietly, of course–in the various reading rooms. Working from Susan’s book outline and several lengthy lists of “must-have” images and topics, together we set about to discover anything and everything relating to football in the Library’s collections. This resulted in a preliminary visual file containing no less than 4,000 images, which we later edited down to 390. As with all Library of Congress publishing projects, we tried to include as many “never before seen” materials from as many different divisions and collections as possible. We also like to use a diverse range of formats: photos, drawings, cartoons, books, maps, sheet music, etc. I’m very pleased with the book and grateful to have had another rich research adventure, in such good company.

How have developments in image technology changed the field of photographic research?

The remarkable developments in technology have changed how all research is done. Image research has evolved from fifth-generation photocopies—snail-mailed—to digital images snapped on a camera and sent immediately to smart phones. This ongoing evolution in the technology, along with researching such a variety of subjects for different clients and purposes has kept me interested and engaged in image research.

April 11, 2014

Copyright Deposit Sets Record Straight on Noted 20th-Century Song

(The following is a guest post by Wendi A. Maloney, writer-editor in the United States Copyright Office.)

The Library’s “Songs of America” online presentation highlights how copyright records can help to shed light on American culture and history. The exhibit draws on hundreds of thousands of pieces of sheet music and sound recordings registered for copyright since 1820 to explore the American experience through song.

William Grant Still. 1925. Prints and Photographs Division.

One copyright record has an especially interesting story. William Grant Still – cited as the “dean of African American composers” in the Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia – registered his composition “Grief” on June 15, 1953, depositing an original unpublished manuscript with the Copyright Office. He wrote the music for a poem by LeRoy V. Brant.

The Oliver Ditson Music Company first published the song in 1955. A version published afterward, however, introduced an error. The final note of the vocal line in that version does not match the one before it, creating a dissonance that extends a mood of sadness through the song’s end.

“This incorrect version of the song was widely performed and came to be considered authoritative,” said James Wintle, a Music Division reference specialist. “For more than 50 years, the mistake was unknown by the public.”

Still’s family, however, felt certain he did not mean for his composition to end the way it was being performed. Judith Anne Still, William’s daughter, turned to the Library’s Music Division for help in 2009.

“She knew about the copyright registration and wanted to find the deposit to show her father’s intention for the song,” Wintle said.

A search succeeded in locating the deposit and proving Judith Anne Still right. The original composition ends on a consonant note, suggesting a “sense of rest and relief” that resolves grief, Wintle said. “It vastly changed the way an important 20th-century composition is interpreted.”

[image error]

“Grief,” by William Grant Still. 1953. Music Division.

After learning of the discovery, baritone Thomas Hampson came to the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium in 2009 to record the original version of the song. A recording of his performance is available online.

“Grief” is but one of many musical accomplishments in the stellar career of Still. He was the first African-American composer to have a symphony performed by a professional orchestra. Wintle notes that the Music Division holds the original handwritten manuscript of Still’s Symphony No. 1, the “Afro-American,” performed at Carnegie Hall in 1935. Still was also the first African- American to have an opera nationally televised and the first African-American symphony- orchestra conductor, according to the Performing Arts Encyclopedia. In addition, he set to music many poems of the Harlem Renaissance, including those of Langston Hughes, and he scored films and arranged commercial music throughout his career. Still died in 1978.

April 10, 2014

Stay Up With A Good Book

The Library of Congress National Book Festival, as you’ve no doubt heard, is going to a new place in 2014 — the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. — on Saturday, Aug. 30 from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m.

[image error]

“Lydia Reading” by Mary Cassatt

As always, it will be free and open to the public, courtesy of the event’s wonderful sponsors. And it will be convenient to two subway stations, Mount Vernon Square on the Green and Yellow Lines and Gallery Place/Chinatown on the Red Line.

And that’s not all that’s new about it!

The new venue has made available space for several new genre pavilions. In addition the longtime pavilions History & Biography, Fiction & Mystery, Poetry & Prose, Children’s, Contemporary Life, Teens and Special Programs, this year’s festival also will offer new pavilions focused on Science, the Culinary Arts, Small Press/International and for children, Picture Books.

The popular and the comfortable will still be there — the book-signings, the Library of Congress Pavilion, the Pavilion of the States and our “Let’s Read America” area with sponsors’ activities for kids. But for the first time in its 14-year history, the festival will offer evening activities between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. including a poetry slam, a panel talk and screening we call “Great Books to Great Movies,” and a “super-session” for graphic-novel enthusiasts. Hence the theme of this year’s festival, “Stay Up With a Good Book.”

But wherever and whenever you hold it, the Library of Congress National Book Festival is first and foremost about books and their authors.

What a lineup of authors, poets and illustrators we have for you this year! It’s not complete yet, but here it is so far: U.S. Reps. John Lewis and James Clyburn, Alice McDermott, co-authors Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes, Peter Baker, Ishmael Beah, Kai Bird, Billy Collins, Kate DiCamillo (the Library’s National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature), Francisco Goldman, Henry Hodges, Siri Hustvedt, Cynthia Kadohata, George Packer, Lisa See, Maria Venegas, and Gene Luen Yang — plus the colossally talented illustrator Bob Staake, who’s just finishing up the artwork for this year’s Library of Congress National Book Festival poster, by the way.

Not to mention Bob Adelman, Paul Auster, Andrea Beaty, Eula Biss, Kendare Blake, Paul Bogard, Jeffrey Brown, Peter Brown, Eric H. Cline, Bryan Collier, Raúl Colón, James Conaway, Ilene Cooper, Jerry Craft, H. Allen Day, Liza Donnelly, Margaret Engle, Percival Everett, Jules Feiffer, David Theodore George, Carla Hall, Molly Idle, Peniel E. Joseph, Nick Kotz, Nina Krushcheva, Louisa Lim, Eric Litwin, Adrienne Mayor, Meg Medina, Claire Messud, Anchee Min, Elizabeth Mitchell, Richard Moe, John Moeller, Bryan Lee O’Malley, Alicia Ostriker, Laura Overdeck, Dav Pilkey, Paisley Rekdal, Amanda Ripley, Cokie Roberts, Ilyasah Shabazz, Lynn Sherr, Brando Skyhorse, Vivek Tiwary, David Treuer, Ann Ursu, Lynn Weise, Rita Williams-Garcia, Natasha Wimmer, Jacqueline Woodson and Tiphanie Yanique.

An array of generous sponsors is the reason the festival can be free and open to the public — including our amazing benefactor David M. Rubenstein, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, The Washington Post, Wells Fargo, the National Endowment for the Arts, PBS KIDS, Scholastic Inc., the Harper Lee Prize for Legal Fiction and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

We’ll be updating the authors and other details about the festival at its website. Keep an eye on the site, and save that date — Saturday, Aug. 30.

America At Play

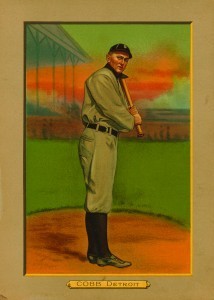

Ty Cobb, Detroit Tigers, baseball card portrait, 1911. Benjamin K. Edwards Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

As major league baseball prepared to celebrate what it thought was the sport’s centennial in 1939, it relied on a 1907 Mills Commission report that credited Abner Doubleday as the game’s inventor. The commission had accepted a personal account from Abner Graves that placed Doubleday in Cooperstown, N.Y., where he supposedly spent the summer of 1839 creating the national pastime. Had baseball officials consulted with Library of Congress staff, they might have dug up irrefutable proof that baseball’s tangled roots in America did not originate with Doubleday on a New York farm, but instead lie deep in colonial-era soil and—yes—England.

Two items available to researchers in 1939, and now in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division, would have been useful in debunking the Doubleday myth. One is the diary of John Rhea, a student at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). Writing in his diary on March 22, 1786, Smith noted that it was “A fine day play baste [sic] ball in the campus but am beaten for I miss both catching and striking the Ball.” The other is a copy of the first American edition of , in which a rhyme titled “Base-Ball” is accompanied by a woodcut image of three players at what appear to be short wooden posts, or bases. The work had originally appeared in London 43 years earlier.

In a country as sports-minded as the United States, the nation’s library documents that passion in myriad formats, housed in various divisions, located in three buildings on Capitol Hill and several preservation facilities in Maryland and Virginia.

Two women compete in a roller derby match in Madison Square Garden. 1950. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

“The Library of Congress has the most extensive sports holdings in the country—much of which has been acquired through copyright deposit,” says reference librarian Darren Jones, the Library’s recommending officer for sports and recreation. “It allows us to get things other people don’t have.”

Thus, scholars researching any sport—and especially its presence in American culture—should consider paying a visit to the Library of Congress.

Here one finds scholarly treatises on ancient athletics, early rule books and commentary on the “new” field of “physical culture,” comprehensive 19th-century baseball-card collections, oral histories, memoirs, and municipal and private athletic-club directories.

Game films, photographs, and radio and television broadcasts—including the first televised NFL game, played in 1939 between the Philadelphia Eagles and the Brooklyn Dodgers—chronicle the growth of both American athletic competition and sports media. Sports in the arts can be found in conference and league maps, posters, juvenile literature (starring Jack Standfast and Frank Merriwell), pulp fiction, comic books, original newspaper sports-page artwork and cartoons, and sheet music for fight songs and team anthems.

Poster promoting the Summer Olympics in Moscow. 1980. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library also holds official International Olympic Committee reports and an unmatched selection of sports periodicals, such as “Spirit of the Times,” which debuted in 1831 and favored horseracing.

And there are books from A to Z—”Aborigines in Sport” (1987) to “Zinger: A Champion’s Story of Determination, Courage, and Charging Back” (1995), the autobiography of golfer Paul Azinger. In between are such items as “The Art of Swimming” third edition (1789), “The Game of Croquet: Its Appointments and Laws” (1865), “Hold ‘Em Girls! An Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Men and Football” (1936) and “Roaring Game: A Sweeping Saga of Curling” (2008).

Notable sports holdings in the Library’s Manuscript Division include the Branch Rickey Papers and the Jack Kemp Papers. Rickey made history in 1945 when he broke the Major League Baseball color barrier by signing Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers. His papers include his scouting reports of Hank Aaron, Sandy Koufax and Willie Mays as well as a large collection of Robinson material. Kemp, star quarterback for the Buffalo Bills before he became a New York congressman, cabinet member and vice-presidential candidate, held onto his high school game programs and professional football contracts. Harry Blackmun’s papers include his college diary, in which the future U.S. Supreme Court associate justice chronicled his adventures during Prohibition as an usher and ticket-taker at Harvard football games, where, as he observed, “the liquor flew muchly.”

Several recently acquired sports broadcasting collections, featuring sportscasts from the 1920s to the early 21st century, continue to enhance the depth and variety of the Library’s holdings.

Champion golfer Katherine Harley, Chevy Chase, Md. 1908. George Grantham Bain Collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

And there’s more for sports enthusiasts to cheer about. The Library is currently selecting and digitizing approximately 600 sports books published before 1923 that will soon be available to researchers online.

MORE INFORMATION

Research Sports, Recreation and Leisure on the Library’s website

This article, written by Susan Reyburn, writer-editor in the Publishing Office at the Library of Congress, is featured in the March-April 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

April 9, 2014

The Sound of Freedom: Marian Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial

(The following is a guest post by Audrey Fischer, editor of the Library of Congress Magazine.)

As the Library of Congress prepares to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with a new exhibition (opening June 19), it’s worth remembering a moment in history when the specter of segregation still loomed large.

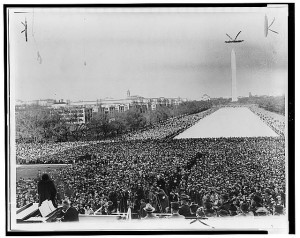

Washington’s prominent figures listen to Marian Anderson’s singing. April 9, 1939. Prints and Photographs Division.

On April 9, 1939, renowned contralto Marian Anderson (1897-1993) performed an Easter Sunday concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The event, which was broadcast nationally by radio and drew an integrated audience of more than 75,000, almost didn’t take place.

Several months earlier, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) barred the African- American singer from performing her Howard University-sponsored spring concert at DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C.

Anderson, who had begun singing in church at the age of six, had already toured Europe to rave reviews, performed with the New York Philharmonic and had sung at Carnegie Hall. (She would, in 1955, become the first African-American to perform at the Metropolitan Opera House). Nonetheless, the DAR would not budge on its “whites only” clause governing use of the concert hall.

Marian Anderson singing at Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., April 9 before 75,000 persons. Prints and Photographs Division.

Reaction was swift. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) rallied support for the singer and worked to secure another venue. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her DAR membership in protest. She worked with NAACP Secretary Walter White and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes to arrange the outdoor concert. The performance, which coincided with the anniversary of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, became a symbol of the struggle for racial equality. Anderson’s repertoire began with the patriotic “My Country , Tis of Thee” and included three Negro spirituals. She closed with “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.”

Housed in the Library of Congress, the NAACP Records include a letter from Walter White to Mrs. Roosevelt, dated April 12, 1939, thanking her for her role in making the Anderson concert possible. He also expresses his delight that the First Lady agreed to present Anderson with the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal at the organization’s annual convention in July. The letter was on display in the Library’s 2009 exhibition commemorating the NAACP’s centennial.

In 1943, a mural by Mitchell Jamieson commemorating the 1939 concert was presented by Interior Secretary Ickes at an event honoring Anderson. That year, Anderson made her first appearance in Constitution Hall at the invitation of the DAR. Her concert benefited United China Relief.

Marian Anderson, (lower left), standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial with back to camera, facing the Washington Monument and a crowd of thousands. 1939. Prints and Photographs Division.

Anderson, who performed at the inaugurations of Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy, returned to the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963, to perform at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom – another event in the long struggle for civil rights. That same year she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Kennedy.

In 2001, the Librarian of Congress selected footage of Anderson’s 1939 concert for inclusion in its National Film Registry, and in 2008, the radio broadcast of the event was included in the National Recording Registry.

A concert marking the 75th anniversary of Anderson’s 1939 concert will be held April 12, 2014, at DAR Constitution Hall, hosted by Grammy-award-winning opera singer Jessye Norman.

April 8, 2014

InRetrospect: March 2014 Blogging Edition

March came in like a lion with lots of interesting posts in the Library of Congress blogosphere. Check out this selection:

Inside Adams: Science, Technology and Business

Carl Sagan, Imagination, Science, and Mentorship: An interview with David Grinspoon

Guest blogger Trevor Owens interviews astrobiologist David Grinspoon, who knew Carl Sagan as a child.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

Works by Leon Battista Alberti – Pic of the Week

The Law Library recently acquired a compilation of Alberti’s lesser-known works.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Happy Birthday, Web!

The Signal celebrates the 25th anniversary of the World Wide Web.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Bringing History and Dance Together: The World of Katherine Dunham

Students can use to dance to study history.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints and Photos

St. Patrick’s Day in the Army

Kristi Finefield looks at how Union soldiers celebrated March 17.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress

In Praise of Detective Peter, or How We Get By With a Little Help from Our Friends

A Library reference librarian solves a literary mystery.

Folklife Today

Narratives of Women and Girls: the Center for Applied Linguistics Collection

Stephanie Hall highlights interviews by women in honor of Women’s History Month.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers