Library of Congress's Blog, page 164

February 18, 2014

My Job at the Library: Karen Keninger

Photo by Shealah Craighead

Karen Keninger, director of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped in the Library of Congress, discussed new technological developments in the interview excerpted below.

What are your responsibilities as the Director of the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped?

The National Library Service (NLS) program has approximately 120 staff members and so part of my job is to oversee the whole program, including the staff in Washington, D.C. And then we have about 100 libraries throughout the country that are cooperating with us to provide our services. So, my job is to oversee that entire program and to look at what’s coming up in the future and plan.

Can you describe the career path that led you to this position at the Library?

I began my career path toward this position when I was seven years old and got my very first books in braille from one of the cooperating libraries in the National Library Services network. That was the beginning of my love for this program, which now serves over half a million Americans who can’t read standard print because of visual or physical disabilities.

The NLS recently organized the first-ever braille literacy conference. What were the goals and outcomes of that conference?

The braille program needs to be modernized. Toward that end, the conference brought together about 100 people from various corners of the braille world who looked at the whole issue of braille literacy from a number of angles. The goal was to have this group tell us what they thought NLS particularly, and the world of braille in general, should be doing to carry it forward into the 21st century. We spent three days talking about it from a number of different angles and we got, what I believe, were some very solid recommendations from the group.

What were some examples of the recommendations given?

One of the top recommendations was that NLS should provide a braille e-reader for people who could use it throughout the country. Braille e-readers are expensive right now and they’re not available to the average reader that we have because of the cost and NLS is not in a position to do that at the moment. But as the technology improves and changes … we will be able to look at that kind of service.

When you were first named director, you said that one of the goals of NLS was to enhance the technologies available to NLS patrons. Are there any technologies that NLS is working on that may be available in the future?

One of the things that we’ve done is develop an app for the iPhone/iPad/iPod family. With that app, you can read our braille and audio books. With the braille books, you need a braille display to go with it, but I think the mobile apps are going to be very popular.

You also said you want to increase NLS readership by 20 percent in five years. What is NLS doing to reach that goal?

One of the things that I think is going to increase the readership is the apps for the iPhone and the Android systems. I think that’s going to attract a group of people who are currently not using our programs because they’ll be able to download directly from our BARD (Braille and Audio Reading Download) website. We also are working with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and we will be helping them to distribute a currency reader as part of a project that they have.

(The following is a story from the January-February 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. You can download the issue in its entirety here.)

February 12, 2014

Conservation Corner: Historical Book Repair

(The following is a guest post by Dan Paterson, preservation specialist in the Book Conservation Section of the Conservation Division.)

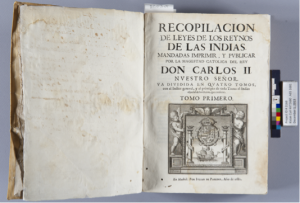

In preparation for display, Conservation Division staff recently treated a historical 17th century book of Spanish laws for governing settlements in the New World. “Recopilacion de Leyes de Los Reynos de Las Indias,” printed in Madrid in 1681, has been added to the “Exploring the Early Americas” exhibition. The book is from the Jay I. Kislak collection housed in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

According to John Hessler, curator of the Kislak collection, the translation of the title is “Collection of the Laws of the Kingdoms of the Indies” and is an extremely important compendium. The book was brought together under the reign of Charles II and is a compilation of all the laws that had been drafted by the Spanish in the New World since its discovery. Containing copies of all the laws, privileges and charters for the running of settlements in the Indies, this volume provided information on every possible facet of community planning and as such gives incredible insight into how the Spanish administered the first settlements in the New World, updating the information found in much earlier documents like Columbus’ Book of Privileges, which is also a collection of legal documents.

All books that are selected for exhibit undergo a conservation review. During this process, conservators identified numerous problems with “Recopilacion” to be addressed before safely displaying the item.

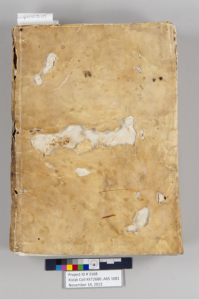

Note the holes on the left side of the cover. The sewing supports should be visible there but they are missing. Loss in the vellum is particularly visible in the center.

The volume is in its original limp vellum binding, a common style for books from Spain during the 17th century. Limp vellum covers were the least expensive way to bind a book based on the cost of the vellum and the time required to complete the binding. There were some annotations and glosses in the text and on the flyleaf. Because of their presence, and the rather pedestrian binding, the book was likely a “use” copy and referred to often – not something that sat on a bookshelf.

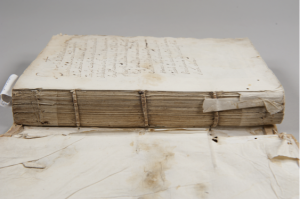

There were several failures with the binding that subsequently caused damage to the text pages. The most significant problem was the break and loss of the original sewing supports, as highlighted in the image to the left. The sewing supports serve as the primary attachment between the cover and the block of text pages. Frequent use would contribute to them breaking. Without the supports, the cover had separated completely from the text, as seen in the image below right. Also, the vellum had shrunk and wrinkled significantly. Vellum is very sensitive to moisture and reacts badly to getting wet. These large losses, visible in the image to the left, threatened the text pages underneath. There are stains throughout the text pages that suggest the book was exposed to water at some point. That exposure was likely a contributing factor to the shrinkage of the cover. As a result, the edges of those pages are now flush with the cover and without protection.

In addition, the first leaf and the title page had numerous tears and losses along the right side of the book. The first leaf was also breaking away from the text block at the spine edge, and the last leaf of the volume had significant tears and losses throughout.

It’s fortunate that it was never rebound, because that evidentiary value may have been lost if it had been put into a more expensive binding at a later date.

The failure of the sewing supports caused the cover to completely detach from the text block.

The tears and losses to the text block were repaired first. Mends were made using long-fibered Korean paper and wheat starch paste. The spine edge of the first leaf was repaired so that the page could be turned without fear of causing further deterioration. The back page was flattened and stabilized, also using mends made from Korean paper and starch paste.

Once the pages were stabilized, new sewing supports were added. The supports were attached to the original ones using unbleached cotton thread, sewn through the original sewing holes and wrapped around both the original supports and the new material. In order to reattach the vellum cover, the lacing holes were repaired and the losses to the vellum were also filled in at the same time. Finally, the repaired cover was laced back onto the text pages in the traditional manner.

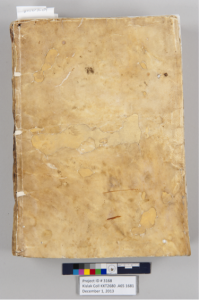

The front cover after repairs have been made. The vellum is now attached to the text block with new sewing supports on the left. Losses to the vellum have been filled.

The final treatment decision was whether to address the shrinking of the vellum. It is possible to carefully and in a controlled manner expose vellum to humidity and gently stretch it back to a larger size. However, due to the extensive damage to the vellum where the losses had occurred, it was determined this procedure would be too risky and potentially cause more harm than good. Instead, a custom fitting box was made for long-term storage and to protect the text block edges and prevent further damage.

Now in its display case, the volume is safely supported by a plexiglass cradle measured and designed to fit the book exactly. Following the exhibition, the book will be returned to the Rare Book Division and available for researchers.

The opening displayed in the exhibit. Mends were applied to the fore edge to stabilize the page and prevent further tearing or loss.

February 11, 2014

A Novel Approach: The Library in Fiction

(The following is a story written by Abby Yochelson, reference specialist in English and American Literature in the Humanities and Social Sciences Division, for the January-February 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. You can download the issue in its entirety here.)

From murder to alien attack, the Library of Congress has provided novelists with fodder for fiction.

Margaret Truman put the nation’s library in the title of her book, “Murder at the Library of Congress” (1999). David Baldacci gave the Library of Congress increased visibility by putting its Main Reading Room on the cover of “The Collectors” (2006). These two novels are the only books in the Library of Congress online catalog rating a subject heading of “Library of Congress—fiction,” but many others have scenes set at the nation’s oldest federal cultural institution.

“Murder at the Library of Congress” follows several murders—including that of a Hispanic Division employee—connected to the pursuit of the diaries of Christopher Columbus, rumored to be housed in the Library.

The fictional Rare Book and Special Collections librarian Caleb Shaw is briefly introduced in Baldacci’s “The Camel Club” (2005), the first in a series of thrillers featuring a group of four eccentric crimesolvers. The Library’s role grows considerably in “The Collectors,” the second book in the series, which investigates the death of the head of the Rare Book Division. In the next installment, Baldacci incorporates the newly opened U.S. Capitol Visitor Center (CVC) into the plot as the tunnel connecting the CVC to the Library of Congress becomes the setting for a shoot-out in “Stone Cold” (2008).

Dan Brown’s “Lost Symbol” (2009) also makes use of the tunnel, providing protagonist Robert Langdon with an escape route from the Capitol. Brown’s description of the history of the Library of Congress and the art of the Jefferson Building is so detailed that he could be mistaken for a Library docent. In another scene, Langdon escapes from the Main Reading Room on a book-conveyor system, which would be an unprecedented use of this technology.

The Library’s labyrinthine bookstacks have stimulated novelists’ imaginations for decades. In R.B. Dominic’s “Murder, Sunny Side Up” (1968), a character observes that “there are corners in this pile where a body could lie undisturbed for months.” This time, it’s Members of Congress who are found murdered in the wake of congressional hearings on a new egg-preservation technique.

The Library affords fictional assailants with unusual murder weapons. A fire-hose nozzle in the bookstacks is used for the first murder in Francis Bonnamy’s “Dead Reckoning” (1943). A leaded weight used to hold down maps is the weapon of choice in “Murder at the Library of Congress” and an unusual fire-suppression system is employed in “The Collectors.”

Long before Hollywood produced “National Treasure: Book of Secrets,” novelists saw the potential for finding clues in the pages of a book. In Ellery Queen’s story, “Mystery at the Library of Congress,” (Argosy, June 1960), researchers use the Library’s books to pass secrets. This plotline is also used in “The Collectors.” A family diary and Bible housed in the Library highlight a conspiracy stretching back centuries in Glen Scot Allen’s “The Shadow War” (2010).

Brad Meltzer’s “Inner Circle” (2011) is a political thriller that focuses on secrets hidden in the National Archives. However, the plot involves a fictional Library employee who provides information about the reading habits of a 19th-century researcher. That information would never be provided by an actual Library employee!

Fictional researchers come to the Library of Congress to find treasure maps, learn about pre- Columbian sites, examine a 19th-century Japanese diary and read espionage thrillers for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in James Grady’s “Six Days of the Condor” (1974).

Second only to murder mysteries, the genre of science fiction makes most use of the Library as a setting. Science-fiction novels run the gamut in envisioning the Library of the future from a dead depository providing useful clues to the past, a working library with 24-hour service or the ultimate electronic repository of information—either all freely available or available at great cost.

The future Library of Congress and the CIA are depicted in Neal Stephenson’s “Snow Crash” (1992). The reader is told that at some point in history the Library merged with the Central Intelligence Agency. With all information digitized, commercialized and sent to the Central Intelligence Corporation, the words “library” and “Congress” have ceased to exist and all information from the CIC is for sale. The term “LC” is used as a measurement of data meaning information equivalent to all pages of material that had been deposited in the Library of Congress.

In contrast, Bruce Sterling’s “Heavy Weather” (1994) depicts all of the information at the Library of Congress digitized and freely available in 2031. “The Puppet Masters” (1951) by Robert Heinlein shows an America of 2007 under attack from another planet, but the Library’s comprehensive historical collections—on microfilm—provide the key to defense. Even Heinlein’s vivid imagination did not predict the world of computers and the Internet.

In reality and fiction, the Great Hall of the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building is a prized venue for special events in Washington. An event in Ellen Crosby’s “The Viognier Vendetta” (2010), which marks an important donation to the Library, is set in “the beautiful Italian Renaissance-style library with its paintings, mosaics, and statuary depicting mythology, legend, and flesh-and-blood icons of poetry and literature.” In Michael Bowen’s “Corruptly Procured” (1994), a bomb provides a diversion to cover the theft of the Gutenberg Bible during a G7 summit reception held at the Library.

With its unparalleled collections and magnificent spaces, the Library of Congress is sure to be cited in works of fiction and nonfiction in the future.

READER CHALLENGE

Readers who come across additional references to the Library of Congress in literature are encouraged to contact Abby Yochelson at ayoc@loc.gov.

February 7, 2014

Celebrating African American History: Rich Library Resources

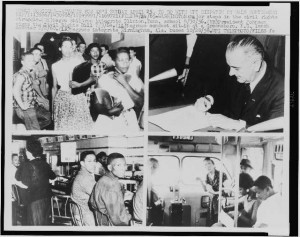

Composite of four photographs relating to the Civil Rights movement during the 1950s and 1960s. Prints and Photographs Division.

February is African American History Month, an annual celebration that has existed since 1926. This year’s theme, according to the Association for the Study of African American Life and History is “Civil Rights in America.”

Much of the credit for commemorating African-American heritage can go to historian and Harvard scholar Carter G. Woodson, who, in 1926, organized the first annual Negro History Week, which took place during the second week of February. He chose this date to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, two men who had greatly impacted the black population. Over time, Negro History Week evolved into today’s African American History Month.

The Library houses the most comprehensive civil-rights collection in the country: the original papers of the organizations that led the fight for civil liberties, such as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; the National Urban League; the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights; the microfilmed records of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Martin Luther King Jr.; the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); and the personal papers of Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, Roy Wilkins, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Arthur Spingarn, Moorfield Storey, Patricia Roberts Harris, Edward W. Brooke, Thurgood Marshall, Robert L. Carter and Joseph Rauh.

Since 1964, the Library has served as the official repository for the NAACP Records. The collection consists of approximately 3 million items spanning the years 1842-1999, with the bulk of material dating from 1919 to 1991. Included are manuscripts, prints, photographs, pamphlets, broadsides, audiotapes, phonograph records, films and video recordings. The NAACP Records are the largest single collection ever acquired by the Library and the most heavily used. The NAACP Records are the cornerstone of the Library’s unparalleled resources for the study of the Civil Rights Movement.

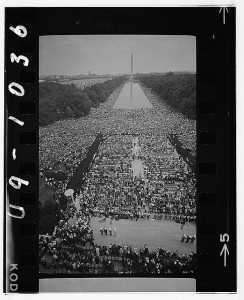

Civil rights march on Washington, D.C. Photo by Warren K. Leffler. Prints and Photographs Division.

The list of Library resources and collections could go on and on. The digital collections of the Library contain a wide variety of material related to civil rights, including photographs, documents, and sound recordings. This guide compiles links to civil-rights resources throughout the Library of Congress website. In addition, it provides links to external Web sites focusing on civil rights and a bibliography containing selections for both general and younger readers.

Currently on exhibit is “A Day Like No Other: Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington,” to document the largest non-violent demonstration for civil rights that Americans had ever witnessed.

In partnership with several institutions, including the Smithsonian and National Archives, the Library has pulled together even more to recognize African-American heritage and achievement. Highlighted are presentations on the Underground Railroad, African American veterans and documentary films on the Civil Rights Movement.

February 6, 2014

Library in the News: January 2014 Edition

With the new year, the Library of Congress rang in lots of news. Here is a sampling of the headlines.

The Library last month announced its acquisition of the collection of jazz great Max Roach.

“Admiration, invective, scrutiny — the sense you get is of a man determined enough to take it all,” wrote Ben Ratliff for the New York Times after having an opportunity to go through some of the archive.

Brett Zongker of the Associated Press caught up with the Library’s jazz curator, Larry Appelbaum, to talk about the importance of Roach and his collection.

“He’s a major figure, not just in jazz but in American music,” said Appelbaum.”Max represented much more than just a musician or even a composer. He was at the nexus of music, civil rights and black power because he was among that wave of socially conscious musicians.”

News of the acquisition also appeared in The Washington Post and D.C. jazz blog, CapitalBop.

In science-related news, Science Friday ran a feature on physicist Carl Haber and his pioneering work in extracting sound from historic audio recordings – many in the Library of Congress’s collections – using Haber’s IRENE, a preservation technology that can create a digital audio file from the analog information found in the grooves of an audio disc. (You can read more about it in these Library of Congress blog posts here and here.) Haber was as the Library last fall working on a collection of audio recordings held by the National Museum of American History, produced by the long-defunct Volta Laboratory.

“Haber and his teammates are working on an unusual disc from the Volta collection, made of bookbinder’s board topped with wax—it looks like a primitive record. Wearing purple surgical gloves to protect the media from the griminess of human hands, a curator takes the recording and places it on a clear plastic turntable connected to specialized optical equipment,” wrote reporter Andrew P. Han. “She must be careful—nobody really knows what is on these files.”

Also spending time at the Library were astrobiologists Steve Dick and David Grinspoon, incoming and outgoing astrobiology chairs at the John W. Kluge Center, respectively. The Washington Post’s Joel Achenbach moderated an event last month featuring the two scientists.

“Yesterday I moderated a discussion about astrobiology at the Kluge Center of the Library of Congress and lobbed questions at two eminent astrobiologists, Steve Dick and David Grinspoon. Here’s one: ‘If you were to make contact with an alien civilization, what’s the first question you’d ask?’” Achenbach wrote. “I always thought we’d want to know what the aliens were made of – whether they had DNA, for example, and were carbon-based and water-based, and so on. But Grinspoon suggested a more practical question: How do we become sustainable?’

“That’s not really a science question, but it’s the one we should all be asking. It’s the question that pulls in science, technology, engineering, political science, social science, and efforts on behalf of human rights, justice and education.”

On the literary front, the Library in January named Kate DiCamillo as the new National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature.

“The huge popularity of young-adult books like ‘The Hunger Games’ series might leave the impression that children’s literature needs no added promotion,” said Julie Bosman for the New York Times. “But librarians and reading advocates say children’s books are constantly under pressure from other forms of entertainment like video games and television, a collective feeling that prompted the Library of Congress and other groups to form a new post in 2008 dedicated to promoting literature for children.”

“‘Stories connect us,’ DiCamillo says, and she believes this so strongly that she’s decided to make it the platform of her two-year ambassadorship. She hopes to encourage communities to engage in reading projects together — retirement homes reading with elementary schools, or entire towns launching on the same book,” wrote Monica Hesse.

DiCamillo also spoke with Jeffrey Brown of PBS Newshour: “I want to remind people of the great and profound joy that can be found in stories, and that stories can connect us to each other, and that reading together changes everybody involved.”

InRetrospect: January 2014 Blogging Edition

The Library of Congress welcomed the new year with a variety of blog posts. Following are a sampling of stories.

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Beautiful Dreamer: Remembering Stephen Foster

Cait Miller commemorates the 150th anniversary of the composer’s death.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

I’ll be damned if I don’t do it!”: The Failed Assassination Attempt on President Andrew Jackson

Robert Brammer looks back on the failed attempt on the seventh president’s life.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Rescuing and Digitally Preserving the Cultural Heritage of the Great Smokey Mountains

Efforts are being made to preserve the culture of the western North Carolina Smokey Mountain Region.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Kate DiCamillo: Stories Connect Us

Rebecca Newland, the Library of Congress 2013-14 Teacher in Residence, talks about using the works of the children’s author in the classroom.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints & Photos

Flickr Commons: What’s New!

Helena Zinkham gives an update on the successful social media community.

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress

In Praise of the Occasional Thursday Night Players

Rob Casper talks poetry with a group of enthusiasts.

Folklife Today

Play Ball! … Aboard Ship?

Sports play a big part in military culture.

February 5, 2014

American History, an-NOTE-tated

The history of America is reflected through its songs. From changes to the “Star Spangled Banner” as played by different bands in different eras, to sheet music art documenting historical themes, the tapestry of American culture and life has been woven through music.

New to the many online offerings of the Library of Congress is “The Songs of America” presentation, which explores American history through song recordings, videos, sheet music and more. From popular and traditional songs, to poetic art songs and sacred music, the relationship of song to historical events from the nation’s founding to the present is highlighted through more than 80,000 online items and is documented in the work of some of our country’s greatest composers, poets, scholars and performers.

Calling the Library an “unbeatable destination for music lovers,” singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash introduces the “Songs of America” website.

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/131206...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

Highlights of the presentation include the first music textbook published in colonial America (1744), Irving Berlin’s handwritten lyric sheet for “God Bless America, The library’s collection of first edition sheet music by Stephen Foster” and performances by baritone Thomas Hampson and soprano Christine Brewer.

Of the presentation, musician Michael Feinstein said, “We can learn about so much that is important for our world today because as Irving Berlin once said, ‘History makes music and music makes history.’”

{

shortName: '',

detailUrl: '',

derivatives: [ {derivativeUrl: 'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/blogs/131206...'} ],

mediaType: 'V',

autoPlay: false,

playerSize: 'mediumWide'

}

Users can listen to digitized recordings, watch performances of artists interpreting and commenting on American song, and view sheet music, manuscripts and historic copyright submissions online. The site also includes biographies, essays and curated content, interactive maps, a timeline and teaching resources – including a handy educator’s guide – offering context and expert analysis to the source material.

As you can image, the Library blogosphere is excited about this new resource and will be producing related posts. Make sure to check back here for updates once they are published.

In the Muse: The Library of Congress Presents the Songs of America: “The Teddy Bear’s Picnic”

Teaching with the Library of Congress: Songs of America: A New Online Collection from the Library of Congress

Folklife Today: The American Folklife Center Participates in “The Library of Congress Celebrates the Songs of America”

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry Widely Featured in the Songs of America Project

February 3, 2014

Curious Collections

(The following is a story written by Jon Munshaw, former intern in the Office of Communications, for the January-February 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. You can download the issue in its entirety here.)

Tom Thumb and his bride, Lavinia Warren, in wedding attire. 1863. Prints and Photographs Division.

Some unusual items in the Library’s non-book collections will amaze and amuse researchers.

Most people know the Library of Congress for being, well, a library. And being a library, there are tons of books. But along with volumes on bookshelves there are a number of quirky artifacts—to be found across all Library divisions—that are less well-known to Library visitors.

A piece of Tom Thumb’s wedding cake is preserved in the Manuscript Division. The 2-foot-11-inch man—star of the P.T. Barnum shows in the 1860s—married the similarly sized Lavinia Warren. Their nuptials created quite a media sensation when they wed on Feb. 10, 1863. The once edible artifact, now black with mold, still remains as a reminder of the occasion.

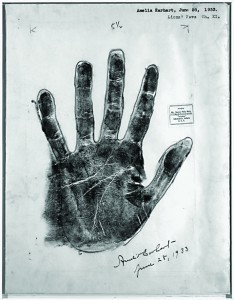

Amelia Earhart’s palm print and analysis of her character prepared by Nellie Simmons Meier. June 28, 1933. Manuscript Division.

The Manuscript Division is also home to Amelia Earhart’s handprint, taken by palmist Nellie Simmons Meier in 1933—four years before the aviator disappeared over the Pacific Ocean. According to Meier, Earhart’s rather large hands indicated a love of physical activity and a strong will. The original prints and character sketches included in Meier’s book, “Lions’ Paws: The Story of Famous Hands” were donated to the Library. (You can read more about Earhart’s handprints here.)

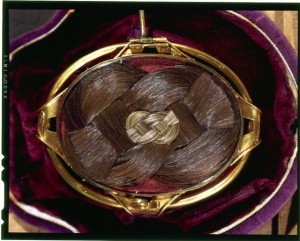

The Music Division houses 26 strands of hair from composer Ludwig van Beethoven. The hair is part of the papers of John Davis Batchelder, a collector of musical autographs and manuscripts. Batchelder’s father received the hair from a friend who brought it to Beethoven’s funeral and almost got into a fistfight over its ownership. The Library also holds locks of hair from the heads of Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

Verso of oval portrait miniature in gold case, showing James Madison’s hair in braided pattern. 1783. Prints and Photographs Division.

The heaviest, and perhaps most poignant, item in the Library’s collection is a 400-pound beam from the World Trade Center, in the Prints and Photographs Division. Photographer Carol Highsmith put the division in touch with company officials in charge of recycling the steel from Ground Zero. The beam, which is stored off-site because of its size, was part of the Library’s Sept. 11 exhibition in 2002.

January 31, 2014

All That Jazz

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell, editor of the Library of Congress staff newsletter, The Gazette.)

Jazz’s greatest drummer once earned D’s in music in school, once wrote an essay entitled “I Hate Jazz” and once even launched a venture to break into the soft-drink market.

Max Roach performs at the Three Deuces club in New York in 1947. William P. Gottlieb Collection / Music Division.

The Library of Congress on Monday announced the acquisition of the papers of Max Roach, the groundbreaking drummer who helped birth bebop, the adventurous musician who never stopped innovating, the educator who inspired new generations and the civil-rights activist who insisted on freedom now.

Roach’s five children – Daryl, Maxine, Raoul, Ayo and Dara – appeared in the Members Room of the Jefferson Building to celebrate his legacy and to check out a few of the 100,000 items in the collection – including dad’s eighth-grade report card, his ruminations about jazz and the promotional material for Afro Kola (slogan: “The Taste of Freedom”).

“As a drummer, composer, bandleader, educator and activist, Max Roach had a profound impact on American music,” Librarian of Congress James H. Billington said. “His collection will have high research value not just for musicians and jazz scholars, but for anyone exploring the rise of political consciousness among African-Americans in the post-World War II period. His collection will now be preserved in the nation’s library so that his legacy and works might inspire generations to come.”

Roach grew up in New York and got a musical education in the clubs of 52nd Street, where almost every great jazz singer or player of the era performed.

“I attended the university of the streets in the ‘Harlems’ of the USA,” Roach wrote on a hotel stationery pad, now part of the Library collections. “My professors were Duke Ellington, Sonny Greer, Baby Dodds, Louis Armstrong. … My classmates were Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Charlie Mingus, Thelonius Monk, Miles Davis.”

In 1942, at age 18, he filled in with the Duke Ellington Orchestra at the Paramount Theater.

In the years that followed, Roach performed with jazz’s giants on some of their greatest records: Davis and “Birth of the Cool,” Ellington and “Money Jungle,” Monk and “Brilliant Corners,” Sonny Rollins and “Saxophone Colossus” and – especially – the 1940s sides with Parker, Gillespie and Coleman Hawkins that helped create modern jazz. On those early records, Roach pioneered a new approach to drumming – he didn’t just accompany, he led. He could play any tempo and any time signature, and his lighter, propulsive sound gave the other players more space to solo.

“He was one of the great African-American creators of the modern jazz style known as bebop,” said Larry Appelbaum, a senior reference specialist in the Music Division.” He not only set very high standards for his technical prowess, but also for his vision, innovations and collaborations.”

Roach reinvented jazz drumming, then embarked on a musically adventurous career spent breaking other barriers.

Roach was among the first to use jazz as a voice for racial equality: His album “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite” marks a musical milestone in civil rights.

He formed a 10-member drum ensemble, M’Boom; composed music for plays and dance; performed with a string quartet that included daughter Maxine; worked with avant-garde musicians; played drums for spoken-word concerts and recordings featuring the works of Toni Morrison and Martin Luther King Jr; and incorporated elements of hip-hop and poetry into his music.

He later taught music at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Roach made his final recording in 2002 and died five years later at 83.

Members of Max Roach’s family (onstage) take in a film clip featuring their father on drums. Photo by Shealah Craighead

On Monday in the Members Room, Roach’s children reflected on his life and legacy. They recalled growing up around some of the great figures in African-American culture: chess games with Gillespie, musical advice from Davis, a visit at home by James Baldwin, a babysitting session with Mahalia Jackson.

“It seemed normal,” Maxine said. “We were fortunate. We just met these people.”

The family first considered the Library of Congress as the permanent home to Roach’s papers in 2010, when Maxine attended a Library event celebrating the acquisition of saxophone great Dexter Gordon’s papers.

“I was so warmly received,” Maxine said. “I was given a tour. My impression after leaving the library was that this was one of the sanest places I’ve ever been in my life.”

The collection contains some 400 linear feet of musical scores, photos, audio recordings, video recordings, business plans, lesson plans and correspondence that define Roach’s life and times. It holds many important items – the holograph score for Roach’s groundbreaking “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite,” an unreleased recording of legendary pianist Hassan Ibn Ali, and an unpublished draft of his autobiography, among others.

The collection also includes a fascinating assortment of odds and ends that reveal his life, music and the music business: that early report card (he earned an A in “civility” and a D in music); an address book (Josephine Baker and Miles Davis face off on opposite pages); receipts noting payments to sidemen (trumpeter Freddie Hubbard got $3,500); a contract for a gig at the Blue Note in Philadelphia ($1,500 for two weeks).

The papers also illustrate a man deeply concerned about jazz, African-American culture and their place in the United States. His “I Hate Jazz” essay explores not a dislike for the music but the racial and economic implications of the term: “ ‘Jazz’ has always meant the worst of working conditions for our artists,” he wrote.

In another essay, he wondered, “What does it mean economically when black musicians espouse and perform the music of anyone other than black composers?”

Roach’s children said he felt a strong sense of the importance of jazz in American music and that he meticulously documented his experiences for the benefit of future generations and researchers – dedication that produced the collection acquired by the Library this week.

“It speaks to his passion to be recognized as not only a hard-working musician all his life, but a human being as well,” Maxine said. “He fought for that on so many levels. That was always the focus: dignity as an artist and a human.”

January 30, 2014

Finding Our Place in the Cosmos with Carl Sagan

(Trevor Owens, digital archivist with the Library’s National Digital Information and Infrastructure Preservation Program and special curator for the Library of Congress science literacy initiative, contributed to this blog post.)

“We are a way for the cosmos to know itself,” once said American astronomer Carl Sagan. Profoundly interested in the universe and our place in it, the celebrated scientist, educator, television personality and prolific author was a consummate communicator who bridged the gap between academia and popular culture. The Library of Congress acquired his papers last year thanks to the generosity of writer, producer and director Seth MacFarlane.

Today, the Library has launched an online collection showcasing selected items from the Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive, along with elements from other important science-related collections at the Library.

Online visitors can view some 300 items, including rare books, manuscripts and celestial atlases, early science fiction books and pop-culture items and such personal items of Sagan’s as journals, loose notes, letters and a full draft of his science fiction novel, “Contact.” The website includes three primary sections. The first presents the Library’s models of the cosmos throughout history. The second explores the history of the idea of life on other worlds. The third focuses on Sagan’s life and works as part of the tradition of science, his education, his mentors and the scientists he mentored.

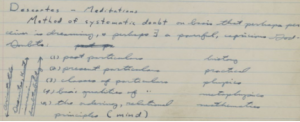

Sagan’s notes on Rene Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy.

Featured in the collection are Sagan’s University of Chicago undergraduate notebooks, which offer a rare opportunity to gain insight into his studies and thoughts. Together they are a testament to the variety and range of his interests as a college student. Notes on course work and other random thoughts offer an engaging way to see how the young astronomer’s ideas and approaches were developing.

For instance, turning through the pages of Sagan’s notes on Rene Descartes’ Meditations on First Philosophy, one finds detailed notes on philosophy, sociology, population genetics and economics in between pages littered with mathematical equations. Sagan mixes commentary on Aristotle, astronomy, genetics and psychology with descriptions of his dreams, commentary on particular pieces of music, drawings, and plans for what courses to take and graduate programs he might enroll in.

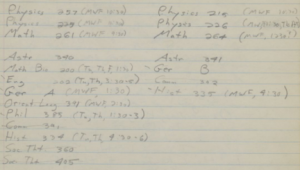

Sagan’s list of courses and programs to enroll in.

These notebooks show Sagan’s diverse interests colliding on the page. On one page, he makes references to an article from a 1952 issue of the science fiction magazine Astounding Stories called “The Tiniest Time Traveler,” suggests that Sadi Carnot’s contributions to thermodynamics were critical to industrial development of 19th century, and jots down the melody for Felix Mendelssohn’s “The Hebrides.”

The broad liberal arts education Sagan received at the University of Chicago played an important role in his development as a scientist and intellectual. As he went on to become a prolific scientist and spokesperson for science, it is clear that this liberal arts perspective is evident in his work.

[image error]

Mendelssohn’s “The Hebrides” joins notes on thermodynamics and popular science fiction.

Also included in the online presentation are a set of short narratives explicating the history of astronomy, notions of life on other worlds and Sagan’s place in the tradition of science.

Through the selected items in this presentation, visitors can explore connections between some of Carl Sagan’s work communicating about the cosmos and the possibilities of life on other worlds and the extensive diversity of collections of the Library of Congress.

To read more about the online collection, Carl Sagan and his profound effect on the science and education community, make sure to read these stories by these Library of Congress blogs.

Inside Adams: Take a Course or Two with Professor Sagan

Folklife Today: Alam Lomax and the Voyager Golden Records

From the Catbird Seat: Space, Time and the Poet Sagan

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers