Library of Congress's Blog, page 160

May 9, 2014

Inquiring Minds: The Intrepid Explorer

(From time to time, we’ll feature the story of one of our many researchers here at the Library and the discoveries they made using our collections. The following is the story of Meg Kennedy Shaw, who conducted research on her father, a British desert explorer, botanist and archaeologist.)

Meg Kennedy Shaw has made many trips to the Library of Congress, “a favorite destination” of hers in Washington, D.C.

W. B. Kennedy Shaw taking theodolite observations from which to compute latitude and longitude. c. 1935. Courtesy of Meg Kennedy Shaw.

“Early on, I fell victim to the exquisite beauty of its great hall, staircases, Bibles gallery, the [Main] Reading Room and exhibitions,” she said.

Shaw accompanied her husband to the area in 2010, when he was awarded a one-year congressional fellowship working as a science advisor to a senator.

“Imagine my delight upon discovering that the [Main] Reading Room was open to all upon presentation of an easily-obtained Reader Registration Card!” she said.

It was during this time she began to research her father, W. B. Kennedy Shaw.

“When researching my father’s work in the Middle East in the 1920s and 1930s, in preparation for my family’s 2009 extensive expedition into Egypt’s western desert, I realized that there were many publications by and about him of which I was unaware,” Shaw said. “Then, when I moved to Capitol Hill for a year, it became obvious to me that if I were ever to find these publications they would be at the Library of Congress.”

According to Shaw, her father was born in 1901 and spent much of his early adult life as an explorer, geographer, cartographer, archaeologist and botanist in the deserts of Sudan, Palestine, Egypt and Libya. His knowledge and understanding of survival and travel in these waterless interior areas was so detailed that he was recruited in 1940 for intelligence work in a special-forces unit of the British Army.

Working with reference librarians at the Library of Congress, Shaw found scientific journal articles her father authored, both familiar and unfamiliar. These also led her to additional resources by her father, his colleagues and earlier explorers.

“I discovered many more publications by and about my father than I had previously known existed,” she explained. “Additionally I learned that he published not only accounts of exploration and mapping in Sudan and Egypt, but he also researched and made discoveries in botany, rock painting and engraving, archaeology, ethnography and geology – even one article speculating upon the political future of Libya.”

During his career, Shaw’s father also contributed to several British government maps, several of which are in Shaw’s collection.

“In preparation for our family’s Egyptian deep-desert expedition, I consulted those maps of my father’s that were in my possession,” she said. “One important map, though not unknown to me, was missing from my collection. On one visit to the Library, the helpful staff in the Geography and Map Division found this map in their collection, which they digitized and reproduced for me.”

W.B. Kennedy Shaw, left, with other participants in Sudan and Egypt expedition. 1935. Courtesy of Meg Kennedy Shaw.

Shaw believes her research conducted at the Library helped her gain a much better understanding of her father, particularly the importance and depth of his pre-war and wartime work accomplishments.

“It’s critically important for the Library to keep an eclectic and comprehensive collection,” she concluded. “In this way, research opportunities are available for that small number of people with an esoteric, specialized knowledge or interest, as well as for those seeking a more general education.”

May 8, 2014

Library in the News: April 2014 Edition

The Library made several major announcements in April, including new additions to the National Recording Registry.

The addition of the 25 new recordings to the National Recording Registry brings the list to a total of 400 sound recordings. Among the new selections were Jeff Buckley’s haunting single “Hallelujah” from his one and only studio album; Lyndon B. Johnson’s massive collection of presidential conversations; Isaac Hayes’ landmark soundtrack album “Shaft”; and “The Laughing Song” performed by the nation’s first black recording artist

Linda Ronstadt’s album, “Heart Like a Wheel,” was also added. The singer spoke with the Los Angeles Times following the announcement.

“Ronstadt, upon learning that her album is now among 400 titles from more than a century of recorded music history elected to the Registry, told The Times with a laugh, ‘If I’d known that, I would have sung it better. But I’m delighted.’”

CBS This Morning got a sneak peak at the recordings from Gene DeAnna, head of the recorded sound section in the Library’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

Other national outlets running features included USA Today, CBS Evening News, Variety, Washington Post and Rolling Stone, among others.

Affiliates of FOX, NBC, ABC and CBS news ran stories nationwide in addition to a variety of local print outlets.

On the literary front, the Library awarded the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction to author E.L. Doctorow.

Doctorow told the New York Times that “the prize was particularly important to him because the nominees were chosen by past winners and other esteemed authors and critics.”

Also running a story was The Washington Post.

Continuing to make the news was Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey, who soon ends her second term as the national poet. She spoke with The Washington Post on all things poetry.

“My friends will sometimes tease me by calling me PLOTUS,” she said.

In addition, her poetry series with PBS NewsHour, “Where Poetry Lives,” launched a new installment in April highlighting the struggles of the civil rights movement.

A new exhibition that opened in April, “A Thousand Years of the Persian Book,” offers a glimpse into the rich literary tradition of the Persian language.

Radio Free Europe featured a pictorial tour of the exhibition.

Lastly, the Library’s rich musical collections were showcased in an article by the Huffington Post. Tony Woodcock, president of the New England Conservatory of Music, wrote about a recent trip to the Library’s Music Division and the musical treasures he had the opportunity to see first-hand.

“It was more like seeing and touching the still beating heart of a masterpiece,” he wrote of viewing the original manuscript of Brahms’ violin concerto.

“It’s all there for everyone. You can look at original scores online and you can go and visit and have the same experience we had. The Library of Congress is there for us all, and it’s one of the most compelling reasons to keep going back to D.C.”

May 7, 2014

First Drafts: “The Way We Were”

The following is an article featured in the May – June 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

“Daydreams light the corners of my mind.”

[image error]

“The Way We Were,” Holograph lyrics, Alan and Marilyn Bergman, 1973. ASCAP Foundation Collection, Music Division.

These might have been the lyrics sung by Barbara Streisand in the 1973 film “The Way We Were” if not for the minds—and pens—of songwriting team Marilyn and Alan Bergman. But the word “daydreams” was changed to “memories” and the result was the Academy Award-winning song, “The Way We Were” (autographed score pictured here) from the film of the same title.

The Bergmans’ personal and professional collaboration, which began in the late 1950s, continues today. Lyricists for film, stage and television, they have earned 16 Academy Award nominations, multiple Emmys, Grammys and three Oscars.

[image error]

Alan Bergman, Marilyn Bergman and Marvin Hamlisch accept the Academy Award for “Best Song,” 1974. ASCAP Foundation Collection, Music Division.

The Bergmans have also devoted their lives to the rights of creative artists and the preservation of their work. Alan Bergman serves as a member of the Library of Congress National Film Preservation Board. Marilyn Bergman was elected president and chairman of the Board of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1994, after five terms as the first woman ever to serve on ASCAP’s Board of Directors. After leading the organization for 15 years, she continues to serve on ASCAP’s Board. In 2002, she was appointed to chair the inaugural Library of Congress National Sound Recording Preservation Board.

The Library of Congress is home to the ASCAP Foundation collection. The organization, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year, is the subject of a Library online exhibition.

May 5, 2014

Go See “Now See Hear!” Now

Today the Library adds another entry in its growing family of blogs.

“Now See Hear!” gives our specialists in the Library of Congress National Audio-Visual Conservation Center a place to showcase some of the amazing treasures of our national audiovisual heritage.

This is a place where Fugazi, Louis Armstrong, Jack Benny, Carole King, Buck Owens, Edward R. Murrow, Aretha Franklin, Mary Pickford, Dick Cavett, Carl Sagan, and Big Bird all share the same stage. We’ve captured their work on film, video, audio disc, wire, tape or CD, and will share news, stories and lessons learned.

Have a look at our first posting.

May 2, 2014

Photos Document Japanese-American Wartime Internment

(The following is a guest post by Wendi A. Maloney, writer-editor in the United States Copyright Office.)

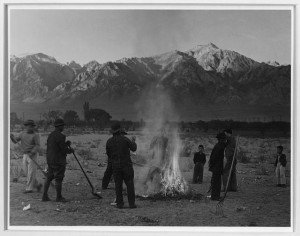

Manzanar Relocation Center, California / Photograph by Ansel Adams. 1943.

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. This annual recognition of Asian Pacific Americans’ contributions to the American story started with a 1977 congressional resolution calling for a weeklong observance. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush extended it to the entire month of May.

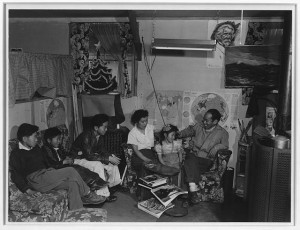

At the Library of Congress, Asian American Pacific Islander resources include books, oral histories, personal papers, community newspapers and many other materials housed throughout Library divisions. Ansel Adams’s World War II photographs of Japanese-American internment in Manzanar, Calif., are a notable inclusion. They bear witness to a sad chapter in our nation’s history – but an important one to document.

Renowned for his images of western landscapes, Adams donated this rare and stunning set of photographs to the Library between 1965 and 1968, placing no copyright restrictions on their use. The complete collection is available through the Prints and Photographs Online Catalog.

Several months after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, more than 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry were forced from their homes on the West Coast and sent to “relocation centers” by the United States government, which had declared war on Japan.

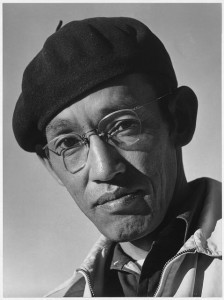

Toyo Miyatake / Photograph by Ansel Adams. 1943.

Documents accompanying the Adams online photo collection say the evacuation “struck a personal chord” with Adams after an ailing family employee was taken from his home to a faraway hospital. When Ralph Merritt, director of the Manzanar War Relocation Center, invited Adams to document camp life, he welcomed the opportunity. He shot more than 200 photos, mostly portraits, but also scenes from daily camp life with the majestic Sierra Nevada mountains often visible in the background.

One striking portrait features Toyo Miyatake, a fellow photographer and internee whose story of resolve under hardship is noteworthy. Miyatake operated a successful photography studio in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo neighborhood before the war. He smuggled a lens into Manzanar and constructed a makeshift camera – internees were not permitted to have cameras in the camp. When Miyatake was discovered, he was allowed to continue and took about 1,500 photographs over more than three years.

Miyatake’s son Archie has said that his father felt a duty to document camp life “so this kind of thing will never happen again.” Toyo Miyatake and Adams became friends, and Adams used Miyatake’s camp darkroom.

Like Adams, Miyatake shot photos of daily life. Some reviewers have noted an edgier tone to Miyatake’s pictures, however. The mountains around the camp often appear menacing in contrast to Adams’s more pristine views. And one well-known Miyatake photograph shows three boys standing behind barbed wire, even though camp rules prohibited photos of barbed wire or guard towers.

Toyo Myatake / Photograph by Ansel Adams. 1943.

Miyatake returned to Los Angeles with his family in 1945, reopening his Little Tokyo studio and achieving acclaim as a chronicler of the Japanese-American community. He died in 1979. In 2011, a street in Little Tokyo was named after him.

As for Ansel Adams, he told an interviewer in 1974 that “from a social point of view,” his Manzanar photos were the “most important thing I’ve done or can do, as far as I know.”

For more resources on Asian Pacific American cultural and historical heritage, visit www.asianpacificheritage.gov.

May 1, 2014

Jewish American Heritage: A Surviving Text

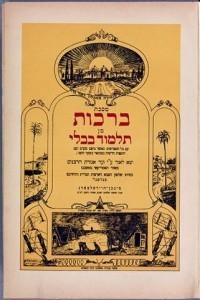

Title page of the first of nineteen volumes of the Talmud. The drawing at the bottom of the page shows a Nazi labor camp lined with barbed wire; the image at the top portrays palm trees and a panorama of the Holy Land.

May marks Jewish American Heritage Month, and this year’s theme, designated by the Jewish American Heritage Month Coalition, honors the 100th anniversary of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).

From its founding in 1914 to aid starving Jews in Palestine and Europe during World War I to life-saving rescues during war years to settling immigrants in search of freedom, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) has worked to aid Jewish communities.

After World War II ended, JDC began vast relief efforts to serve the hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors worldwide, including Displaced Persons camps in Europe and immigrating survivors to the new State of Israel.

The Library of Congress has a complete copy (in 19 volumes) of an entire Talmud printed in the American Zone just after World War II in a Displaced Persons camp that had formerly been a concentration camp. The edition, often called “The Survivors’ Talmud,” was printed by the JDC, with the active help of the United States Army.

The Talmud (literally, “the study” or “the learning”) is the chief cornerstone of mainstream Judaism. It comprises a huge compendium of legal traditions going back to Jewish antiquity. It was transmitted orally from generation to generation until around 500 A.D., when Jewish sages in Babylonia – then the chief center of world Jewry – committed it to writing. The first complete printed set was accomplished in Venice, between 1521 to 1523, by printer Daniel Bomberg.

Immediately after the liberation of the concentration camps, the survivors tried to rebuild their lives and look to the future. One of their first priorities was to reconstruct their cultural life, so schoolbooks, religious texts, newspapers and periodicals began to be published soon after the camps were liberated.

The most ambitious of these projects was the publication of a full size folio edition of the Babylonian Talmud in 19 volumes. There was an agreement signed in September 1946 by U.S. Army Gen. Joseph T. McNarney and the JDC for a set of the Talmud to be produced under the auspices of the Army. It took longer than expected to produce because of the shortage of paper and the difficulty of finding a complete set of the Talmud in Germany at the time. Eventually it was printed in Heidelberg in 1948 and is the only Talmud to have been published by a national government. Ironically, it was printed by the Carl Winter Printing Plant in Heidelberg, which had previously printed Nazi propaganda. According to the exhibition catalogue “Printing the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein” from Yeshiva Univeristy Museum in New York, only 100 copies were printed.

From the first volume of the Survivors’ Talmud: “In 1946 we turned to the American Army Commander to assist us in the publication of the Talmud. In all the years of exile it has often happened that various governments and forces have burned Jewish books. Never did any publish them for us. This is the first time in Jewish history that a government has helped in the publication of the Talmud, which is the source of our being and the length of our days. The Army of the United States saved us from death, protects us in this land and through their aid does the Talmud appear again in Germany.”

Each volume of the Talmud also included this dedication: “This edition of the Talmud is dedicated to the United States Army. The army played a major role in the rescue of the Jewish people from total annihilation and after the defeat of Hitler bore the major burden of sustaining the DPs [displaced persons] of the Jewish faith. This special edition of the Talmud published in the very land where, but a short time ago, everything Jewish and of Jewish inspiration was anathema, will remain a symbol of the indestructibility of the Torah. The Jewish DPs will never forget the generous impulses and the unprecedented humanitarianism of the American forces, to whom they owe so much.”

For a look into more of the Library’s Jewish history and cultural collections, visit www.jewishheritagemonth.gov.

(Ann Brener, Hebraic area specialist in the Library’s African and Middle Eastern Division, contributed to this blog post.)

April 30, 2014

National Recording Registry: Open to Your Nominations

(The following is a guest post by Steve Leggett, program coordinator for the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress.)

In the weeks since announcing the annual 25 additions to the National Recording Registry the Library has been asked a few questions about rap and hip-hop and its representation on the list. These questions are valid and important to explore.

The 2013 list of 25 additions announced earlier this month did not include a recording in the rap and hip-hop genre. However, the genre has been represented on the registry since the registry’s very first list of 50 recordings was announced in January 2003. In that year, “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five was among recordings including Orson Welles’ radio drama “War of the Worlds” (1938), President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s D-Day radio address (1944) and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech (1963).

The fact that those important and diverse sound recordings stand shoulder to shoulder on the same list is indicative of what the registry is about, and indeed illustrates the very important role sound recordings have played in our collective memory and consciousness since the very first recordings were captured in 1853.

With respect to rap and hip-hop, in addition to “The Message”, the registry also includes Sugar Hill’s 1979 “Rapper’s Delight” – widely credited with launching the genre – plus three others for a total of five. That means of the 17 music recordings in the Registry that date from 1979 or later, about 30 percent represent the rap genre, including the most contemporary recording in the entire registry, Tupac Shakur’s 1995 “Dear Mama.”

It is important to understand that the National Recording Registry is not a “best of music” list. Although much attention each year tends to focus on popular music, the registry is about sound recordings of all kinds – from political speeches to historic firsts, all deserving recognition and preservation.

Of course the registry includes music, but it also showcases Thomas Edison’s recording of 1888 for a talking doll prototype; 1890 recordings of Passamaquoddy Indians – considered the first field recordings; Booker T. Washington’s 1895 Atlanta Exposition Speech (1906 recreation); 1917′s the Bubble Book – the first book/record recorded especially for children; the first transatlantic radio broadcast (1925); the first official transatlantic telephone conversation (1927); Charles Lindbergh’s arrival in Washington, DC (1927); FDR’s fireside chats (1933-44); Neil Armstrong’s broadcast from the moon; and many other historic recordings.

You can view the entire list here.

The process for selecting new additions includes review of public nominations, and active discussions and review by the advisory National Recording Preservation Board, featuring representatives from the recorded sound, preservation and music industries. The Board advises the Librarian of Congress on national preservation policy as well as the National Recording Registry.

Of course, selecting the recordings each year involves a lot of discourse and argument about current representation of various genres, time periods, artists and key cultural and historical themes.

Keep in mind, the National Recording Registry represents a very small slice of the Library’s collection of more than 3.5 million sound recordings or the 46 million recordings held in U.S. public institutions according to a 2005 survey. Many of these recordings are in dire need of preservation, an alarming fact highlighted in the 2013 landmark national recorded sound plan published by the Library. The good news is that virtually any published recording of a song registered for copyright with deposited copies is in the Library’s permanent collections: so much, however, yet remains to be preserved and made available

But the registry, in essence, represents a special category of recordings the Library would seek out and ensure are in our collections in the most pristine form available. So we do like to think of it as an “honor” or recognition of the best of the best in addition to spotlighting countless other worthy recordings. From that standpoint we welcome the fact that critics are looking, well, critically at what is on the list and what is not. Keep that dialogue going!

With only 25 additions each year, the selection process is mighty challenging. And there is no doubt the number of recordings that should be on the registry far exceeds the number of recordings already on the registry.

Along with rap songs that have been mentioned in recent blogs and the public – works by artists such as Lauryn Hill, Run-DMC, 50 Cent, Dr. Dre, Jay-Z, Eminem and Kanye West — this vast treasure trove of cultural importance awaiting recognition consists of radio broadcasts, technological breakthroughs, advertisements, ambient sounds and well-known standards by a stunning litany of music legends.

If you believe rap or hip-hop – or any other genre – is under-represented on the list, please nominate a recording…or several. We are accepting nominations for the next list here.

Remember the recordings must be at least 10 years old. We look forward to hearing from you!

April 29, 2014

A Journey to the Northwest Frontier in 1783: The Journal of George McCully

(The following is a guest post by Julie Miller, early American specialist in the Manuscript Division.)

People who visit the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress often ask where our collections come from. Sometimes the answers are surprising. This is true for a journal kept in 1783 by a Revolutionary War veteran from Pennsylvania named George McCully. The journal, which is currently featured in a Library of Congress exhibition, “Mapping a New Nation: Abel Buell’s Map of the United States, 1784,” came to the Library in a roundabout way.

Many years after McCully’s death in 1793 his widow, Ann McCully, submitted an application for a widow’s pension to the War Department’s Pension Bureau in Washington D.C. To support her application she included the journal. After Ann McCully received her pension in 1837, her application, with the journal, was filed away as entry 7-411 in the Pension Bureau’s “Widow File.” There it remained until 1906, when an official named C.M. Bryant realized that after three-quarters of a century the journal had shed its original function and acquired a new one as a historical document. In 1909 the Pension Bureau transferred the journal to the Library of Congress, where it soon caught the eye of Detroit lawyer and local historian Clarence Monroe Burton. He published it in The Magazine of History in 1910.

McCully’s journal is a record of his trip from Pittsburgh to Detroit in the summer of 1783. McCully went as a companion to Ephraim Douglass, who had been sent by Secretary of War Benjamin Lincoln on a mission to the Indians of the Northwest frontier. Like McCully, Douglass was a Pennsylvanian and a veteran of the Revolutionary War. Secretary Lincoln may have chosen him because he knew him as his aide-de-camp during the war, but Douglass also had the necessary skills: he was an Indian trader (as McCully may also have been), and he knew his way along the trade routes. He also knew the languages of the tribes he was sent to meet with.

Douglass’s instructions were to tell these tribes – many of whom had sided with the British – that now that a treaty ending the war was about to be signed, they would have to accept American sovereignty. This message would be a bitter one for these people to receive. Although many had been important players in the war and all would be profoundly affected by the redistribution of land that followed, they had been excluded from the treaty negotiations then in progress.

As a primary source McCully’s journal has some problems. It is a copy – probably made by Ann McCully – and an imperfect one. A few dates are mixed up, and the journal’s account of the trip goes only from June 7, when Douglass and McCully left Pittsburgh, to July 4, when they were just outside Fort Detroit. But Douglass’s August 18, 1783, report to Secretary Lincoln shows that the little delegation reached Detroit, visited the British commander there then continued on to the British forts at Niagara and Oswego before returning to Princeton, New Jersey, where Congress was meeting. (Are you wondering what Congress was doing in Princeton? See here.)

[image error]

“Indian of the Nation of the Shawanoes.” 1826. Prints and Photographs Division.

McCully’s vivid descriptions make up for the journal’s shortcomings. Despite his sometimes iffy spelling and punctuation, he brings the landscape of the Pennsylvania and Ohio wilderness and its people to life. McCully shows how difficult this landscape was to travel through, even for those who knew the way. The trading path they took from Pittsburgh, where they both lived, was “intricate” and “impossible to follow” since “the bushes were lofty and in many places enterlocked in each other.” Near a place with the picturesque name of Hell Town they “met with intolerable swamps and thickets,” then “lost the road and lost ourselves.” McCully describes a very wet landscape, full of streams and rivers to cross, swamps to get lost in and plenty of rain. On several occasions they had to get themselves and their horses over deep, fast-moving rivers. At Mohican John’s Town in Ohio, heavy rain forced them to spend an extra night with “a large swarm of bees . . . They were our companions during our stay at the place.”

McCully also documented the social complexity of life on the frontier. This was a place where plenty of Indians spoke French, the result of centuries of interaction with French explorers, trappers and missionaries, and it was not unusual to meet white people who wore feathers in their hair. The Delaware, Shawnee and Wyandot lived in this area. So did traders, Moravian missionaries, settlers taken captive by Indian tribes and the agents the British used to manage relations with their Indian allies. This multilingual blend of cultures sometimes produced confusion. McCully describes how one evening when he and Douglass were camped near a stream they heard an Indian call. Douglass replied in the same language, asking the caller to “come up to us,” apparently so fluently that when the Indian arrived he was surprised to find a white man. McCully tells what happened: “Seeing him much alarmed Mr. Douglass and I stepped to him and took him by the hand, told our business, took every method to dissipate his fear.” The Indian, his two companions and McCully and Douglass then spent the evening “very sociably together.”

At a Delaware settlement on the Sandusky River in Ohio, McCully and Douglass met several captive settlers. One woman captive they met there “as soon as she saw us burst into tears and began to make a complaint of ill treatment as though we would have relieved her.” Another “behaved with more prudence and bore her misfortune well.” McCully’s surprising lack of sympathy for these women may be the result of what he knew and what historians have documented about the mixed experiences of white settlers taken captive by Indians. Some, especially women and children, were adopted by their captors, adapted to Indian life and chose to stay, even when they had the chance to return home. Eunice Williams, captured as a 7-year-old from Deerfield, Mass., in 1704, and Mary Jemison, captured in Pennsylvania as a 15-year-old in 1758, are two examples of this phenomenon. McCully may have seen such acculturated captives and reasoned that misery was not a given.

Frances and Almira Hall, taken captive by the Fox and Sauk at Indian Creek, Illinois, 1832. Their experience may have been similar to that of the captives George McCully met on the Sandusky River in Ohio in 1783.

Just as Indian captives could become hybrid figures – at home in more than one world – so could the agents who worked for the British Indian Department. One of these was Matthew Elliot, who McCully and Douglass encountered on their journey. Before the Revolution, according to Clarence Burton, Douglass and Elliot – both Indian traders around Pittsburgh – were “intimate acquaintances.” But early in the war Elliot left Pittsburgh to side with the British while Douglass fought on the American side. Elliot, who lived with the Shawnees and worked for the British at Detroit, developed a fearsome reputation among the Americans. Alonzo Sabine, author of “The American Loyalists; or, Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in the War of the Revolution” (1847) noted his “revengeful disposition and infamous deeds.”

Sabine may have been indulging in colorful hyperbole, but Douglass does appear to have mistrusted Elliot. At Sandusky, Douglass wrote him, asking him to invite the Shawnees to meet with him there. “Though I promised to myself very little from this Letter,” Douglass reported to Lincoln, “I knew it could do no possible harm–and though I did not hope he would give himself any trouble to serve me, I thought the possibility that the compliment of it might prevent his opposition worth the trouble of writing it.” Instead of delivering Douglass’s message to his Shawnee hosts, Elliot, taking orders from Detroit, obstructed him as Douglass guessed he might. After Douglass and McCully left Sandusky for Detroit, they met Elliot on the road. He had been sent from Detroit to conduct them there and, McCully recorded in his journal, “to prevent our speaking with the Indians.”

Joseph Brant, engraving of a portrait by George Romney, ca. 1776. Ephraim Douglass met with Joseph Brant at Fort Niagara, which was in British hands in 1783.

In the end, Douglass’s mission was not a success. Everywhere he went Indian leaders politely rejected his message. The British commanders at forts Detroit, Niagara and Oswego, wanting to maintain their relations with their Indian allies and unwilling to give up their forts (which they held onto for more than a decade after the Treaty of Paris), were not interested in helping. At Fort Detroit commander Arent Schuyler Depeyster (a New York loyalist) told Douglass that “he could not consent that any thing should be said to the Indians relative to the boundary of the United States.” But at Fort Niagara the great Mohawk leader Joseph Brant defied the resistance of the British commander there and came to speak with Douglass. In his report, Douglass described how, in an evening of “friendly argument” Brant “insisted that they would make a point of having them [Indian lands] secured before they would enter into any farther or other Treaty.” Brant later left for Canada, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Even though Douglass’s mission didn’t succeed, it produced one lasting prize, long hidden in the Widow File at the Pension Bureau: George McCully’s perceptive and revealing journal, which shows the land and the original people of Pennsylvania Ohio, and the Great Lakes as they were in the summer of 1783.

“Mapping a New Nation: Abel Buell’s Map of the United States, 1784,” is in the North Gallery, first floor, Thomas Jefferson Building, Library of Congress, Washington DC. “Across a New Nation,” a section of the exhibition’s computer interactive, is based on George McCully’s journal.

April 25, 2014

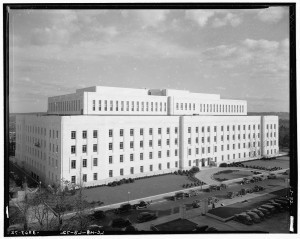

The Library in History: The John Adams Building at 75

The Library of Congress John Adams Building. ca. 1939. Prints and Photographs Division.

Seventy-five years ago, the Library opened a second building on Capitol Hill to house its growing collections.

With a collection of more than 3.5 million items, former Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam reported to Congress in 1926 that the nearly completed bookstack “will not be likely to take care of the accessions beyond the coming decade.” Thus began his push for an Annex Building.

In 1935, Congress approved and President Herbert Hoover signed a total congressional appropriation providing $8,226,457 for the construction of a second building to be located east of the existing building on land that had been acquired in 1928.

Faced in Georgian marble, the building is a wonderful example of the Art Deco design movement, which first appeared in France after World War I. Various artisans and manufacturers contributed to the beauty of the building. The building was constructed under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration, a federal agency that employed millions of unemployed people during the Depression. The project was listed in President Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act, which authorized a variety of public works.

When the building opened to the public on Jan. 3, 1939, it was called “the Annex.” On April 13, 1976, in a ceremony at the Jefferson Memorial marking the birthday of Thomas Jefferson, President Gerald Ford signed into law the act to change the name of the Annex Building to the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building.The original Library of Congress structure was then dubbed “The Main Building.”

The South Reading Room of the Annex Building is a tribute to Thomas Jefferson and was referred to as the Thomas Jefferson Reading Room. His image is captured in a lunette overlooking the reading room.

The designation of the Annex as the Thomas Jefferson Building was short-lived. In the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson had authorized a congressional appropriation of $75 million to construct a third Library of Congress building to be named for nation’s fourth president. In 1980, the James Madison Memorial Building opened to the public and Congress passed a law that changed the names of both existing Library buildings. The main building was named the Thomas Jefferson Building and the Annex became the John Adams Building, in honor of second president John Adams, who, on April 24, 1800, signed the law that established a library for Congress in 1800.

Adams Building doors. Photo by Shealah Craighead.

The building’s classical architecture features a series of large bronze doors depicting the history of the written word in high-relief sculpted figures designed by American artist Lee Lawrie, who is best known for the architectural sculptures on and around New York’s Rockefeller Center.

The doors, located at the entrance to the Adams building, showcase various deities and mythological characters such as Hermes, who was attributed with inventing the alphabet; Odin, the originator of the science of written communication in Norse mythology; and Quetzalcoatl, revered as the inventor of books in Aztec culture.

Under the auspices of the Architect of the Capitol, the bronze doors to the John Adams Building were replaced recently with code-complaint sculpted glass panels mirroring the original bronze door sculptures. The Washington Glass studio and Fireart Glass of Portland, Ore., created the new doors.

The following is an article featured in the March-April 2014 issue of the Library of Congress Magazine, LCM, now available for download here. You can also view the archives of the Library’s former publication from 1993 to 2011.

April 24, 2014

214 Years Young

The Library of Congress celebrates its 214th birthday today. Founded on April 24, 1800, thanks to an appropriation approved by Pres. John Adams of $5,000 for the purchase of “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” What started with a whopping 740 books and three maps has evolved to more than 158 million items, including more than 36 million books and other print materials, 5.5 million maps, 69 million manuscripts, 13.7 million photographs, 6.7 million pieces of sheet music and 3.5 million recordings.

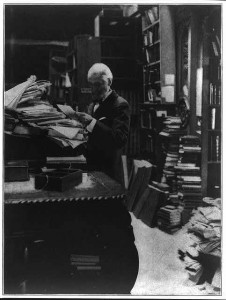

Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford standing amid stacks of books and library shelves. Prints and Photographs Division.

Thomas Jefferson took a keen interest in the Library and its collection while he was president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. In fact, he approved the first law defining the role and functions of the new institution, including the creation of the post of Librarian of Congress. When the British army invaded the city of Washington in August 1814 and burned the Capitol, where the nascent 3,000-volume Library of Congress was located, Jefferson sold his personal library of 6,487 volumes to replace what had been lost.

The Library was housed in the Capitol until 1867. Sixth Librarian of Congress Ainsworth Rand Spofford (1864–97) was the first to propose that the Library be moved to a dedicated building. He also was instrumental in establishing the copyright law of 1870. That year Spofford sent Rep. Thomas A. Jenckes, chair of the Patent and Copyright Committee, a list of reasons U. S. copyright activities should be centered at the Library. When Pres. Ulysses S. Grant signed such a bill, a flood of copyright deposits – books, maps, music, pamphlets – filled the small space assigned to the Library in the Capitol. Overflow was moved to the Capitol attics and along the basement corridors. By mid-decade, Spofford was putting volumes along the walls of committee rooms, down the first- and second- floor corridors and against the public staircases.

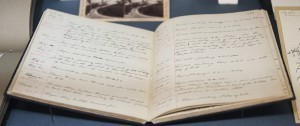

[image error]

William Boyd notes in his journal, “Everything moving along in 1s class shape. Men all working on high pressure …” Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

The Thomas Jefferson Building was built from 1886 to 1897 in the style of the Italian Renaissance. Superintendent of Construction Bernard Green and architect Thomas Casey planned and commissioned the amazing variety and type of sculpture in the Jefferson Building. William Boyd organized much of the sculpture created in workshops – both marble carving and stucco molding – housed in the building. Boyd documented the cost of materials, time and workers involved in creating the hundreds of sculptural details, such as column capitals and figures like the eagle. More than 50 American artisans contributed their talents to the symbolic sculptural and painted decoration of the building.

Men cutting stone decorations for the Library of Congress. Prints and Photographs Division.

Green and Casey selected noted artists for major sculptural works in the building. Among the commissions, Philip Martiny’s cherubs along the grand stairwell and Olin Warner’s spandrel group “The Students,” located directly across the great hall from the main bronze doors, were carved at the Piccirilli Brothers marble carving studios in New York City. Warner’s bronze doors depicting memory and imagination were cast at the John Thompson forge shop in New York. Green recorded the daily progress on the Jefferson Building in his Journal of Operations, including in 1897 that Warner’s “The Students” had arrived from Piccirilli Bros. and was ready to install.

In his Journal of Operations, Bernard Green notes the arrival of Olin Warner’s spandrels. Photo by Amanda Reynolds.

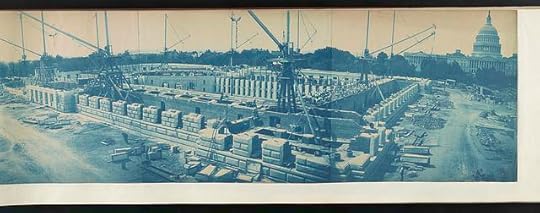

On Nov. 1, 1897, at 9 a.m., the new Library building (now known as the Thomas Jefferson Building) officially opened to the public – 25 years after Spofford had begun his entreaty. Several days later, the transfer of Library materials – some 800 tons – into the new building was completed.

The Library continued to expand its Capitol Hill campus in 1928 and 1971 1957 , with the addition of the John Adams and James Madison Memorial buildings, respectively. You can take a virtual tour of all three here.

Today, the Library’s Hill campus has multiple reading rooms and exhibit spaces available to the public. In 2013, approximately 1.6 million people visited the Library. The Library’s website was visited more than 84 million times that year. Offsite facilities include the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation in Culpeper, Va; vast modular storage at Ft. Meade; and numerous international offices.

For more information on the history of the Library of Congress and its buildings, see “Jefferson’s Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress” and “On These Walls: Inscriptions and Quotations in the Buildings of the Library of Congress.”

Searching the Library’s Prints and Photographs Online Catalog for “Library of Congress” brings forth numerous images of the construction of the Jefferson Building and its architectural drawings, as well as vivid color photographs of the Library’s Capitol Hill campus and buildings interiors.

Builders at work on the rusticated stone walls of the Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building during its construction. Sept. 10, 1890. Prints and Photographs Division.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers