Library of Congress's Blog, page 157

July 31, 2014

Letters About Literature: Dear George Orwell

We’re rounding out our spotlight of letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. National and honor winners were announced last month.

You can read the winning letters from the competition Level 1 (grades 4-6) and competition Level 2 (grades 7-8) here.

The following is the Level 3 (grades 9-12) National Prize-winning letter from Devi Acharya of University City, Mo., who wrote to George Orwell, author of “Animal Farm” and “1984.”

To George Orwell:

You were right, you were right, you were right. I’m sorry I never saw it before, and I feel like an idiot, sitting here and penning this to you when you were so unspeakably right. You shouldn’t have published those books of yours under the guise of fiction—how could fiction be what’s happening outside my very doorstep! People get so worked up, angry at some imaginary oppressive tyrant when the very dystopias we fear and loathe are being built around us. I’m only just beginning to see them myself—brick and mortar meant to keep worlds apart, shields of hatred and arrows of intolerance, warlords arming for battle while the unwitting peasants continue to live from day to day. Soon only the fortress, a bastion cutting down any hope of love or compassion, will remain, with every citizen gripped tight in the steely apathy of law.

Oh, if only I could make you understand just how important—nay, fundamental!—your work has been to my life! If only I knew I would be able to express such a thing in this letter—and it not come across as the ramblings of a madman! What I enumerated before, but feel I have not adequately expressed, is that you were right. I first read “Animal Farm” when I was young—too young to understand it. I thought of it as a humorous fable, nothing more. Every day I saw oppression—in the news, on the street, in my home. Every day I watched as underlings tried to rise above their rulers, getting drunk on power and imposing rule harsher than even that of previous tyrant. I saw the denizens, mindless and dumb, waiting to see who the new ruler would be, wondering if they should care. And in my wide-eyed youth I did not think, “Those are Orwell’s words! Those are the very actions, painted on the canvas of reality! That group is made of pigs, and those other fellows’ horses and goats and sheep. Here is where the story starts, and here is where it will end, every word as he penned it.” My eyes might have been as blind as those vacant stares about me, but to my credit I did observe. I watched people and places and motivations and reactions. I tried to piece my world together through the map you created.

Then came your work “1984.” This piece was the key that turned the lock in my mind, allowing me to see that this was real, that vigilance was needed. I saw in my slovenly compatriots the face of Parsons, and in my fellow youth those trained only to follow orders and the herd under the guise of “teambuilding” and crafting “character.” I saw the posing, the scare tactics, the hypes and hysteria. I saw the pain of real terrorism as it happened, and then saw the far more expansive, far more deadly panic and paranoia of imagined threats of terrorism.

Now what do I see when I dare to venture outside my tiny safe haven? Drones circling overhead. Cellphones that track every move; whose conversations are being recorded and analyzed indiscriminately for any sign of suspicion. More and more information has been released, telling evidence of our descent into dystopia—and yet people seem to become ever more complacent! Scandals blow up in a day and are gone the next. Disaster relief gets attention perhaps only a few months. People would much rather live in an era where superheroes and men with guns can solve all the problems in the world. And I must confess, I can’t blame them for that.

I am not saying, sir, that I think that every aspect of society is awful and must be usurped, countermanded, destroyed. I love this world. That’s why I want to protect it. I am saying (as you have always said) that people must always watch the world around them instead of drifting between obligations and pleasure, as so many do now. That’s the reason I wrote this letter—to say (for it must be reiterated this one last time) that you were right. Right to write your books, right to do all that you have done to better the world. I, too, have begun my first steps in the world of writing, describing the world I see around me just as you did. I hope to be, just as you have been, an observer spinning my cautionary tales, and trying to help the world understand.

You are truly an inspiration. Your words will echo in this world for centuries to come.

Goodbye for now,

Devi Acharya

July 29, 2014

President Harding’s Letters Open to the Public

(The following is an article written by Mark Hartsell for The Gazette, the Library of Congress staff newsletter.)

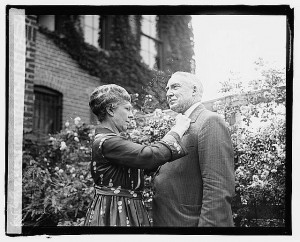

Warren G. Harding / Prints and Photographs Division.

For most of two decades, a future president carried on an affair with a family friend. For 50 years, the love letters they wrote each other – discovered in a closet, sealed by a court order and, finally, locked in a vault at the Library of Congress for safekeeping – have been closed to the public.

Today, the Library opens the letters Warren G. Harding wrote to his mistress, Carrie Fulton Phillips, to the public for the first time since they were sealed by a probate judge in 1964 and later donated to the Library by the Harding family. The Library also has recently obtained a separate collection of material, such as photos and letters, from Phillips’ descendants.

An Affair Between Friends

Harding and Phillips began their affair in 1905 in Marion, Ohio, where both lived. He was the lieutenant governor of Ohio. She was the thirtysomething wife of a prominent dry-goods merchant and mother of a little girl.

The families were close enough to even vacation together in Europe. All the while, Harding and Phillips carried on their intimate relationship.

Harding and Phillips exchanged letters when either was away from Marion, sometimes writing dozens of pages at a time. While Phillips lived in Germany for several years and after Harding was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1914, the affair – and the letters – continued, long distance.

“They talk about their relationship,” said Karen Linn Femia, Library archivist who organized and described the material. “They talk about family things, hometown things, political things, the war in Europe.”

The Harding-Phillips collection at the Library includes about 240 items: drafts, empty envelopes indicating letters not saved, letter fragments and about 100 full letters that total about 1,000 pages.

The letters date between 1910 and 1920. Most were written by Harding, many while he served in the Senate. The affair ended just before he was inaugurated as president in1921.

“It was a 15-year relationship,” Femia said. “We just see the last 10 years. It’s almost sort of like looking in on a marriage, at some point, because it was such a long-term thing.”

Carrie Fulton Phillips / Manuscript Division.

Harding and Phillips remained on cordial terms after the affair ended, as did the families – even though Harding’s wife and Phillips’ husband had earlier discovered the relationship. Indeed, Phillips, her husband and her mother in 1922 visited President Harding at the White House.

Harding’s presidency ended early and tragically: He died of heart failure in 1923 after only two years in office.

Discovery in a Closet

Phillips over the decades became something of a town eccentric, living in Marion in a neglected house overrun with German shepherds. Her health failed, and in 1956 her lawyer and court-appointed guardian moved her to a nursing home.

While preparing for the move, the lawyer discovered a box hidden in the back of a closet. Inside, he found a surprise: a stash of letters from Harding. Not knowing what to do with them, he took them home for safekeeping.

Phillips died in 1960 and, three years later, the lawyer made the letters available to a potential Harding biographer.

Word of the letters’ existence spread and the New York Times eventually wrote a story about them, drawing the attention of the Harding family and Phillips’ daughter, Isabelle Phillips Mathée.

“That’s when Isabelle, the daughter, finds out these letters exist,” Femia said. “That’s when the legal proceedings begin, when the Hardings find out these letters exist.”

A Tangled Web

Warren G. Harding with his wife, Florence, in 1920 / Prints and Photographs Division.

Harding’s nephew, George Harding, brought a lawsuit, thwarting the use of the letters by the biographer. An Ohio probate judge closed the papers on July 29, 1964, as the court tried to determine who, exactly, owned the letters.

Finally, after extended litigation, Harding agreed to purchase the letters from Phillips’ daughter – a settlement that included a 50-year closure, dating from the probate judge’s original sealing in 1964. In 1972, Harding donated the letters to the Library of Congress for safekeeping, with the stipulation that it keep the papers closed for the remainder of the 50 years. The letters have been locked in a Manuscript Division vault ever since. Other copies, however, do exist.

Ohio archivist Kenneth Duckett microfilmed the collection during its temporary storage at the Ohio Historical Society in 1963. Author and historian James D. Robenalt discovered the microfilm in Duckett’s papers at the Western Reserve Historical Society and in 2009 published a book on the subject, “The Harding Affair: Love and Espionage During the Great War,” that contends Phillips may have been a German spy.

“There are aspects of presidents’ personal lives that lead them in a certain direction as far as decisions they make in a political realm,” Femia said. “Scholars may find things here that led Harding in certain ways. There’s importance to that.”

July 28, 2014

See It Now: Historians Discuss Significance of President Harding’s Letters

The Library of Congress will open a collection of approximately 1,000 pages of love letters between 29th U.S. President Warren G. Harding and his mistress, Carrie Fulton Phillips, on Tuesday, July 29. The collection has been locked in a vault in the Manuscript Division since its donation in 1972.

The letters were written between 1910 and 1920 during an affair that began in 1905 between then-Ohio Lt. Gov. Warren Harding and family friend Carrie Fulton Phillips. The vast majority of the letters were written by Harding—many while he served in the U.S. Senate (1915-1921). Additional material from the Phillips/Mathée family will also be accessible to the public on July 29.

On July 22, the Library hosted a symposium on the historical significance of the Harding/Phillips correspondence. The following is a webcast of the program.

{shortName:'',detailUrl:'',derivatives:[{derivativeUrl:'rtmp://stream.media.loc.gov/vod/webcasts/201...'}

Manuscript Division Chief James Hutson moderated the panel, which included Library of Congress archivist Karen Linn Femia, Ohio lawyer and historian James D. Robenalt and Dr. Richard Harding, a grandnephew of President Harding, who made this statement on behalf of the Harding family. Members of the Mathée family provided a statement that can be read here.

July 25, 2014

Slammin’ those Books OPEN!

This year’s Library of Congress National Book Festival is going to segue from a big day of authors for all ages to an evening of excitement – starting with a poetry slam titled “Page [Hearts] Stage” at 6 p.m. in the Poetry & Prose Pavilion.

The festival will be held from 10 a.m.–10 p.m. on Saturday, Aug. 30 at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center in Washington, D.C. It is free and open to the public.

The 2014 National Book Festival poster by Bob Staake

The slam—a contest in which poets read or recite their poems, which are then judged by a panel—will include the District of Columbia’s top youth slam groups: the DC Youth Slam Team and Louder Than a Bomb DMV. Champion delegates from both groups will compete to be named the city’s top youth slammer, by performing new works on the subject of books and reading. The event is a collaboration among the Library of Congress Poetry and Literature Center, The National Endowment for the Arts and the poetry organization Split This Rock. Judges will include national and international slam champion Gayle Danley, Tanuja Desai Hidier, author of “Born Confused,” and Maryland State Sen. Jamie Raskin. The emcee for the slam will be Beltway Grand Slam champion Elizabeth Acevedo.

The poetry slam is among this year’s first-ever nighttime activities in the 14-year history of the Library of Congress National Book Festival. This year’s festival theme is “Stay Up With a Good Book.” The event will take place in the Poetry & Prose Pavilion sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts.

And that’s not all! Evening activities will include a Graphic Novels Super-Session with Michael Cavna, author of The Washington Post’s Comic Riffs blog, as master of ceremonies, presented with the assistance of the Small Press Expo. The Washington Post is a charter sponsor of the festival.

Other festival events between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. will include a session featuring “Great Books to Great Movies” moderated by Ann Hornaday, film critic for The Washington Post, with panelists E.L. Doctorow, Alice McDermott, Paul Auster and Lisa See.

There will also be a session celebrating the 100th anniversaries of the births of three literary giants of Mexico—Octavio Paz, Efraín Huerta and José Revueltas—in collaboration with the Mexican Cultural Institute.

The festival will feature more than 100 authors of all genres for readers of all ages. The Walter E. Washington Convention Center is accessible via Metro on the Red Line (Gallery Place) and the Green and Yellow Lines (Mount Vernon Square/7th Street/Convention Center).

Letters About Literature: Dear Ray Bradbury

In this fourth installment of our Letters About Literature series, we highlight the Level 2 (grades 7-8) National Honor Winner Jane Wang of Chandler, Ariz., who wrote to Ray Bradbury, author of “Fahrenheit 451.”

Dear Ray Bradbury,

“Fahrenheit 451 the temperature at which books burn.” A title that would kindle any curious eighth grader’s interest. Its simplistic, plain back cover showed only a small picture of an ancient, smoldering tome to hint at the plot. It bore the distinct appearance of being one of those antiquated, perplexing novels with a profound theme that would probably make my language arts teacher grow all warm and fuzzy inside but leave my head pounding. But your book was so much more than even that. It was a story of ignorance and knowledge, illusions and reality, misery and happiness. It was a story that changed my perspective of something that had once troubled me very much.

Controversy and debate; I have never liked either of them. It was previously my belief that they had only ever been a nuisance to me and overcomplicated my life. You see, I am a naturally cautious person. I do not enjoy taking risks, and I hate having to make decisions or pick sides for fear that I will regret it later. It has always been a huge burden to me and in my mind; I used to tentatively entertain the notion of a much easier life where only one opinion, one belief, and one answer existed for everything. There would be no more test questions asking “why,” no more arguments with Mom about possibilities for the future, no more discord between countries regarding controversial government programs or questionable laws. After all the absence of furious debates and nasty disputes should lead to a happier, more peaceful, and ultimately better world, right? Wrong. Your novel showed me just how wrong I was.

“Fahrenheit 451″ told the tale of a world where the controversy and debate that had troubled me so much did not exist. But I quickly realized that your book did not tell a happy story. That controversy and debate had been eliminated at the cost of something much more important: free, individual thought. Montag’s wife, Mildred, and the rest of her friends cared about nothing more than their own immediate pleasures. Anything that required even the slightest bit of time or concentration was believed to interfere with the advanced technology, loud music, and fast cars they enjoyed in their fast-paced lives. Literature, self-reflection, and even the simple act of thinking had no place in their world, though they play important roles in mine. I read to learn and grow. I reflect to make myself a better person. And thinking, wondering about the ways of the world as Clarisse did, is something I take for granted. The books that Beatty, Montag, and the rest of the firemen sought to burn have shaped me into who I am today. All my life, I have surrounded myself with books to promote my learning and knowledge of the world; I would be miserable without them. Montag and many others in your novel never had that opportunity to experience such a form of genuine happiness. They never had the chance to spend that time on their own simply sitting in a rocking chair at their own front porch and quietly reflecting. And without that special moment to think and wonder, Montag and everyone else’s mind slowly faded away as they were continually stifled and restrained, their individual thoughts and ideas burned away with books they couldn’t even remember. No wonder all that controversy and debate disappeared; how could there have been any argument regarding any matter if no one knew of any problems to discuss?

Your novel did not change me in a particularly noticeable way. I did not take on a radical new personality or come to any unexpected epiphanies. My peers and others around me still saw the same careful, perfectionist girl they had known before. But underneath all the layers of invisible yellow caution tape that I had wrapped myself up in was a girl with a new perspective. Suddenly, the words controversy and debate did not seem like the very nemeses of my cautious nature. What was once a burden now seems like a wonderful gift to be cherished. “Fahrenheit 451″ showed me what a life without argument would entail. Your novel allowed me to understand that where there are no disagreements, there are no personal opinions, and where there are no personal opinions, there are no individual thoughts.

Furthermore, I realized after reading your book that the events in your novel were not all fictional. Censorship exists in today’s society just as it did in the world of “Fahrenheit 451″; burning books is just a rather extreme version of it. I recognize the fact that there are people who live in places very similar to Montag’s world, where individual thoughts that don’t align with the purported ideals are forbidden. I know now that I am very fortunate to be able to experience the occasional disagreement, because controversy and debate are proof that my thoughts are well and truly my own.

Thank you, Mr. Bradbury, for writing “the novel of firemen who are paid to set books ablaze.”

Jane Wang

Letters About Literature, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives, announced its 2014 winners in June. More than 50,000 young readers from across the country participated in this year’s initiative, a reading-promotion program of the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress.

National and honor winners were chosen from three competition levels: Level 1 (grades 4-6), Level 2 (grades 7-8) and Level 3 (grades 9-12). You can read the letters from the Level 1 winners here and here and the Level 2 National Winner here. In addition, winning letters from previous years are available to read online.

July 23, 2014

America’s Other Anthem

O beautiful for spacious skies,

[image error]

“Sea to Shining Sea,” by L. Stovall, 2008. Prints and Photographs Division.

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

America! America!

God shed his grace on thee

And crown thy good with brotherhood

From sea to shining sea!

Pikes Peak is one of America’s most famous mountains. Rising more than 14,000 feet, the mountain has been designated a National Historic Landmark. The views from the summit have inspired many, including Katharine Lee Bates, who penned the iconic anthem “America, the Beautiful” following a visit to the top in July 1893.

Bates was an English literature professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts and had traveled west to Colorado to teach a summer course. As she told it, “We strangers celebrated the close of the session by a merry expedition to the top of Pike’s Peak.”

She and her band of fellow educators traveled to the top by prairie wagons pulled by horses and mules.

“It was then and there, as I was looking out over the sea-like expanse of fertile country spreading away so far under those ample skies, that the opening lines of the hymn floated into my mind,” Bates later wrote.

She finished the poem before she left Colorado but would not publish it until two years later. Her words appeared in The Congregationalist in commemoration of Independence Day. She went on to revise the poem in 1904 and again in 1913.

Pike’s Peak, Colo. 1899. Prints and Photographs Division.

Bates’ poem was first set to music in 1904 and was typically sung to almost any popular tune, with “Auld Lang Syne” being the most common. In 1910, her words were published as “America, the Beautiful” and set to the tune we know today, which is by Samuel Augustus Ward, a Newark, N.J., church organist and choirmaster. He originally composed the melody in 1882 (also titled “Materna”) to accompany the words of the 16th century hymn “O Mother Dear, Jerusalem.”

A plaque commemorating the words to the song was placed at the summit of Pikes Peak in 1993.

You can read more about “America, the Beautiful” in a special feature as part of The Library of Congress Celebrates the Songs of America collection. Included are audio recordings and notated music.

The Library’s National Jukebox, an online collection of historical sound recordings from Victor Records, also includes two recordings of “America, the Beautiful.”

July 16, 2014

Letters About Literature: Dear Anne Frank

For the last two weeks, we’ve been featuring the winning letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners were announced last month. National and honor winners were chosen from three competition levels: Level 1 (grades 4-6), Level 2 (grades 7-8) and Level 3 (grades 9-12). You can read the letters from the Level 1 winners here and here.

Following is the Level 2 National Prize winning letter from Jisoo Choi of Ellicott City, Md., who wrote to Anne Frank, author of “The Diary of a Young Girl.”

Dear Anne,

I hold your diary in my hands, and I feel as if you are speaking to me from years past. You are telling me how much it annoys you that the van Daans are always quarreling. You’re whispering sadly that you think you will never become close with your mother. Your scream rings in my ear, and the echo tells me you’re tired of crying yourself to sleep. And it tears my heart in half. Thank you for speaking to me. Thank you for your diary. Thank you for your legacy you have left for the world; for me.

I am thirteen years old, the same age you were when you first went into hiding. The same age you were when you set foot into the solitary world you would know for over two years. And at such a young age, your dreams have inspired so many all over the world. And because of you, I have learned not to wait until I am older to achieve my dreams, not to think about “when I grow up, I will…” but to strive to inspire at my age, just as you have. The fact that you have become an amazing, worldwide inspiration both comforts and challenges me.

Reading your account of the two years you spent in hiding, I cried with you, learned with you, dreamed with you. I came to know you and came to appreciate you for who you were. You cried to me so many times about how your family can’t love you for being you. If only you had known that your diary would be published for the world to be inspired by … If only you had known that the “musings of a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl” that you thought nobody would want to read made such a difference on another thirteen-year-old schoolgirl. Anne, in the beginning of your diary, you wrote that you did not have your one true friend. And throughout the progression of your diary, you continuously wished that you could have a friend to confide all your sorrows and aspirations in. That was Kitty.

You thought that the only person reading your letters would be you. Your letters so filled with fantasies one day and frustrations the next. But, Anne, the world has become your Kitty. I have become your Kitty. And I am so grateful.

Every time there’s a disagreement or commotion in the Secret Annex, you always come back to your diary. You’ve even wrote once, “When I write I can shake off all my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived!” As an inspiring writer, just like you, I also find solace in writing. I have school notebooks filled with fragments of ideas for stories, planners with a poem on every other page. But, like you again, I also wonder if I really have talent, worry if I’ll ever be able to write something great. I worry about the same things as you, and although you may have thought they were petty concerns, they’re everything I challenge myself to overcome. And reading your unabashedly honest and real narrative, I found a real friend in you.

As a girl reading your diary over a half a century since you penned them, I know the ending to your story. To the absolutely amazing and inspiring story of your life. And I’m sorry you had to face such injustice. Those who live the most deserving lives always seem to be silenced so unfairly and so brutally. You dreamed so ardently of the days after the war. You wrote yourself to freedom in the space which confined your body but not your soul. I am grateful, for although the world never heard your voice, you have left your words as your story. I’ve gone through hardships in my life as well, though none have been as trying as your years in the Annex, and I’ve gone through them by writing and dreaming my way out, just as you have those long two years. You dared to dream, in spite of the reality that threatened you daily, and you have allowed me to dream as well. “There are no walls, no bolts, no locks that anyone can put on your mind.” You are truly a role model to me. You have shown me the subtle beauties in life. You have let me experience the sheer power of words, the words that connect generations across the globe.

You have left a spark in my heart that will kindle the flames of hope in my darkest days. Whenever I despair, or consider giving up, your voice will be whispering your dreams and hopes, because they are mine also. Anne, you needn’t worry those times when you felt no one understood. Because, dearest Anne, because your Kitty understands.

Jisoo Choi

July 11, 2014

Letters About Literature: Dear Sharon Draper

We continue our spotlight of letters from the Letters About Literature initiative, a national reading and writing program that asks young people in grades 4 through 12 to write to an author (living or deceased) about how his or her book affected their lives. Winners were announced last month.

There was a tie for the national prize for Level 1. Following is one of the winning letters written by Jayanth Uppaluri of Clayton, Mo., to Sharon Draper, author of “Out of My Mind.” You can read the other Level 1 winning letter here.

Dear Sharon Draper,

I don’t have cerebral palsy. I don’t need a device to communicate. I don’t even have a photographic memory. My life is so different from Melody’s life. I can use all of my fingers to type on a computer. I can walk around the block. I can take part in a regular conversation about the St. Louis Cardinals. I don’t need an aide to help me. I have two siblings, a brother and a sister. My sister is about as free of disabilities as you can get. My brother is a different story.

My brother has difficulty in expressing his words because he has a form of autism. Like Melody, he tries to tell people many things, and like Melody he gets frustrated when people don’t understand him. Similar to Melody, he has a device to communicate, but unlike Melody’s, my brother’s device is quite complicated to use. On top of this, he does not always have his device when he needs it the most because the battery can fail at any time.

Because of his talking complications, people don’t understand him, and sadly he gets frustrated. What’s so hard to understand about this? If I had trouble expressing myself, I would be frustrated, too. For example, if I couldn’t tell my parents that I hated peas, and they kept giving me peas, or if I couldn’t tell them that I love eggnog and they kept offering me carrot juice…I think you get the picture. When my brother gets frustrated, he might tear paper or throw things. Sometimes, to get attention, he has even hurt himself by hitting his head or banging his chin. Before I read your book, I never understood how he could survive or how to help him.

Then, I read your book. Though cerebral palsy is different from autism, there are some things in common. People with cerebral palsy or autism are held back by symptoms whether it’s lack of mobility or lack of expression. Also people with autism are not dumb and the same goes for people with cerebral palsy. Reading ”Out of My Mind” gave me a different perspective on things. It is the only book I have read that was from the impaired person’s perspective. I never thought “What is she crying about?” because I could vividly see what Melody was thinking.

Your book made me think differently about my brother and begin to put myself in his shoes. I began to help him express his feelings. For example, when I ask him a question, I give him time to respond rather than ask him over and over again like I used to. I also have learned how to interact with my brother. We wrestle together and chase each other around the house instead of doing things separately. Before I read your book, I didn’t make the effort to play with him. That was a big mistake, because seeing my brother’s winning smile when we played for the first time has made me realize that we have a very special bond that no one can break.

It is important for Melody to feel confident in order to succeed, and that’s very important for my brother too, just as it is for any of us. When Melody participated in the Whiz-Kids competition, her family and caregiver, Ms. Violet, supported her and helped her study, which gave her the confidence to win. It is also vital for my brother to experience success. When he brings my mom the iPad when she wants him to watch videos, we don’t overlook it. We praise him for doing it. This gives him the confidence to do better and progress. If he hides in the closet and stuffs his face with Lindt chocolate truffles without asking, we don’t scream at him. Instead, we take the bag away, tell him to ask us first…then we stuff our faces with chocolate. This doesn’t make him afraid of us, instead it makes him laugh, and it makes us happy because we get to eat chocolate (chocolate equals treasure in our house). When he flashes his million dollar smile at us as we are eating chocolate, it sends an unspoken message that words could never express.

Now I know that my brother can survive. When Melody was in Mr. Dimmwit’s class and everyone thought it was a mistake that she got 100% on the preliminary Whiz-Kids test, she didn’t give up. She studied very hard with Ms. Violet and then aced the final test to get into the Whiz-Kids competition. This made me think that my brother could survive all that he was going through and that people around him would realize how intelligent he is. If Melody could endure all the taunts and insults given by Molly and Claire, my brother can endure the ignorant people who don’t understand him. If Melody can tolerate not making it to the national Whiz-Kids competition, my brother can tolerate his challenges. He works so hard in his therapies, and I am confident it will pay off.

Before I read your book, I thought my brother didn’t understand me. Because he couldn’t talk that well, I didn’t think he could understand anyone. After I read your book, I realized something. I was wrong. He understood me. The only person who didn’t understand anything was me. Thanks for writing this amazing book that helped me to understand my brother.

Jayanth Uppaluri

July 9, 2014

InRetrospect: June 2014 Blogging Edition

The Library of Congress blogosphere helped beat the heat in June with a variety of engaging posts. Here are a sampling:

In the Muse: Performing Arts Blog

Connecting to Samuel Barber: A Young Musician’s Connection to a Musical Manuscript

Music Division intern Rachael Sanguinetti talks about her appreciation of the composer’s works.

Inside Adams: Science, Technology and Business

Getting Around: Presidential Wheels

Read about the cars various U.S. presidents cruised in.

In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress

150 Years of the Arlington National Cemetery — Pic of the Week

The historic cemetery was founded June 15, 1864.

The Signal: Digital Preservation

Web Archiving and Preserving the Performing Arts in the Digital Age

The Library is currently working on a project to preserve performing arts websites.

Teaching with the Library of Congress

Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Fugitive Slave Act

Teacher-in-Residence Rebecca Newland examines the relationship between the novel and legislation.

Picture This: Library of Congress Prints and Photos

Anything to Get the Shot: Volcanic Visuals

How close is to close when documenting an erupting volcano?

From the Catbird Seat: Poetry and Literature at the Library of Congress

Hooray to Our New Poet Laureate!

The Library welcomes new Poet Laureate Charles Wright.

Folklife Today

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: No Need to Be Afraid

June is National Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Awareness Month

Now See Hear!

Remembering Ann B. Davis

Mike Mashon remembers the actress noted for her role as Alice, the Brady Bunch housekeeper.

NLS Music Notes

Braille, and Haüy, and Howe, Oh My!

Katie Rodda takes a look at the history of braille music.

July 8, 2014

LC in the News: June 2014 Edition

The Library of Congress welcomed Charles Wright as the institution’s 20th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry for 2014-2015. Several major news outlets ran stories.

“Our next poet laureate may end up speaking on behalf of the more private duties of the poet — contemplation, wisdom, searching — rather than public ones,” said reporter Craig Morgan Teicher for NPR. “While he might not be planning to pound the national pavement during his laureate year, Wright has plenty to tell us if he lets his poems do the talking.”

“Mr. Wright, who along with his wife, Holly, a photographer, spends part of every summer at a remote cabin in northwest Montana without a telephone, said he would devote some time over the next few months to pondering his new public role,” wrote the Jennifer Schuessler.

reporter Ron Charles spoke with Librarian of Congress James H. Billington on his selecting Wright as Poet Laureate. “As I was reading through the finalists, I always kept returning to this man who wrote so beautifully and movingly about important things without self-importance but with extraordinary skill and beauty.”

In other literary news, the Library also announced in June that approximately 1,000 pages of love letters between 29th U.S. President Warren G. Harding and his mistress, Carrie Fulton Phillips, will be opened July 29 with an event July 22.

Running stories were Politico and USA Today.

Continuing the make headlines are the Library’s audio-visual initiatives and preservation efforts.

The institution recently acquired a video archive of thousands of hours of interviews—The HistoryMakers—that captures African-American life, history and culture as well as the struggles and achievements of the black experience.

“Julieanna Richardson, the founder and executive director of The HistoryMakers, said the Library of Congress was the ideal home for the project,” wrote Tanzina Vega of the New York Times. “‘The slaves will now be joined with their progeny,”’ Ms. Richardson added, in reference to the library’s slave narratives archives, which include more than 2,300 first-person accounts that the Works Progress Administration collected in the 1930s.”

CBS Evening and Morning News also ran a story.

The Library of Congress Packard Campus for Audio Visual Preservation makes regular appearances in the news. CNN reported on its efforts to convert historical analog sound recordings and moving images into digital format in order to preserve them for the future.

“It’s an exhaustive job. Between 1.5 million film, television and video items, and another 3.5 million sound recordings, the 114 staff members here have their work cut out for them” wrote John Bena for CNN. “Collecting and cataloging over 120 years of recorded American history may seem to be a daunting task. But the preservation of these deteriorating items is currently one of the most pressing missions for the library.”

Speaking of early recordings, Boise Weekly reported on the Library’s efforts to make those available online. “The Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., has been ahead of the curve on this trend, placing many of its vast resources on the web, including a gorgeous collection of early video recordings, many of which are well over a century old.” The story included several video clips, including a Sioux Indian dance and Annie Oakley shooting targets.

And, thanks to IRENE, a digital-imaging device, the Library has made strides in preserving sound as well. The Atlantic delved into how the device works and the various mediums the Library has been able to preserve.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers